Abstract

Despite growing support for supervision after task sharing trainings in humanitarian settings, there is limited research on the experience of trainees in apprenticeship and other supervision approaches. Studying apprenticeships from trainees’ perspectives is crucial to refine supervision and enhance motivation for service implementation. The authors implemented a multi-stage, transcultural adaptation for a pilot task sharing training in Haiti entailing three phases: 1) literature review and qualitative research to adapt a mental health and psychosocial support training; 2) implementation and qualitative process evaluation of a brief, structured group training; and 3) implementation and qualitative evaluation of an apprenticeship training, including a two year follow-up of trainees. Structured group training revealed limited knowledge acquisition, low motivation, time and resource constraints on mastery, and limited incorporation of skills into practice. Adding an apprenticeship component was associated with subjective clinical competency, increased confidence regarding utilising skills, and career advancement. Qualitative findings support the added value of apprenticeship according to trainees.

Keywords: Haiti, task shifting, task sharing, training

Introduction

Background

Globally there is a projected shortage of 1.2 million mental health professionals, with this gap being greatest in low and middle income countries (LMICs) (Kakuma et al., 2011; WHO, 2000). This shortage has led to increasing efforts for task sharing of mental healthcare (Patel et al., 2007; WHO, 2006). Task sharing, also known as task shifting, refers to the involvement of non specialist service providers delivering healthcare that traditionally resided within the domain of expert health workers (WHO, 2008). Within the context of global mental health, ‘non specialist’ refers to a person who lacks prior professional or other specialised training in mental healthcare delivery. Non specialists, in both low and high resource settings, may include: community health volunteers, peer helpers, social workers, midwives, auxiliary health staff, teachers, primary care workers and those without a professional service role. Task sharing includes: building human capacity among healthcare workers, enhancing the capacity to provide needed care and strengthening health systems so that scale-up of services is sustainable (WHO, 2008). This approach has been recommended as a pragmatic, cost effective way to assure higher coverage of care in LMICs that bear a large portion of the global burden of mental disorders (Somasundram, 2006; WHO, 2010).

Randomised controlled trials of interventions implemented by non specialists for persons with mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders suggest improvement for some mental health outcomes in LMICs (van Ginneken et al., 2013). Ventevogel and colleagues (2012) argue that individuals with little to no experience in mental healthcare can be trained to deliver services within systems of care that include regular supervision and refresher trainings. A number of resources exist regarding guidelines and appropriate content for mental healthcare interventions in LMICs. The WHO launched the mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) in order to address systematic mental health needs in LMICs, including an intervention guide for general healthcare workers (WHO, 2010). In LMIC settings, such as Haiti, community based healthcare personnel may be ideal for task sharing initiatives as they are more likely to understand (lay) explanatory models and to be able to utilise local idioms of distress (Keys, Kaiser, Kohrt, Khoury, & Brewster, 2012; Kaiser et al., 2014). However, important questions remain regarding the best approach to train non specialist healthcare workers to provide mental health services. Additionally, best practice for mental health training are still under-evaluated, as compared, for example, to guidance provided for task sharing in HIV/AIDS care (Murray et al., 2011; Perez-Sales, Fernandez-Liria, Baingana, & Ventevogel, 2011; WHO, 2008).

Murray and colleagues (2011) argue that existing guidelines are overly broad and limit replication efforts. Lack of adequate evidence results in brief, one time training approaches and a limited participatory framework. Studies from both high-income countries (HICs) and LMICs have shown that such one-off approaches, with little post training supervision, may result in changes in knowledge but rarely in changes in practice (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Budosan, 2011; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010). For more effective and sustainable interventions, mental health training needs to be coupled with continued supervision and assistance from a mental healthcare professional (Baingana & Mangen, 2011; Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp, & Whiteford, 2007; van der Veer & Francis, 2011). In their evidence based review of supervision literature,Milne et al. (2008) stress that the use of multiple training modalities (e.g. instructing, feedback, modelling, observing) are key to effective supervision. Apprenticeship approaches, where training is reinforced through intensive supervision, coaching and feedback, may thus lead to increased fidelity and effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in LMICs and therefore warrant further consideration (Murray et al., 2011).

Currently, there is limited qualitative research describing the process of implementation of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPS)1 trainings and supervision in LMICs within larger systems of care (Flisher et al., 2007; WHO & Wonca, 2008). Therefore, this article attempts to address this gap, by describing a qualitative evaluation of a pilot project and by documenting successes and challenges that arose in the process. As Baingana and Mangen note (2011), there is often a tension in the implementation literature between rigorous quantitative methodologies and more qualitative and participatory methods. This article is therefore designed as a description of a process and is meant to raise critical questions for discussion and reflection regarding task sharing initiatives in LMICs.

Mental health and psychosocial support in rural Haiti

Mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) resources in Haiti are insufficient due to lack of infrastructure, particularly in rural areas (WHO, 2003). Approximately half of rural Haitians lack access to primary care, and mental health services are extremely limited (Caribbean Country Management Unit, 2006). A Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (2003) report estimated only ten psychiatrists and nine psychiatric nurses working in the public sector, most of whom were located in Port-au-Prince. Recent reports suggest slightly higher numbers (around 20 psychiatrists) but still attest to a dearth of mental health providers in the country (WHO, 2011). A local affiliate of Partners in Health (Zanmi Lasante) has recently begun to scale-up community based mental health services in the Central Plateau and Artibonite departments (Raviola, Petersen, Ssebunnya, Bhana, & Baillie, 2012).

When suffering from mental, emotional and physical problems, Haitians often seek care from herbalists (doktè fey), Vodou priests (hougan or mambo) and religious leaders (Bijoux, 2010; Hagaman et al., 2013; Khoury, Kaiser, Keys, Brewster, & Kohrt, 2012; Miller, 2000; Wagenaar, Kohrt, Hagaman, McLean, & Kaiser, 2013). Only 29% of respondents in the Central Plateau said they would first seek care from hospitals or clinics when suffering from psychological distress, as the clinic was perceived to provide strictly biomedical care (Wagenaar et al., 2013). Respondents also reported seeking help from family. These preliminary findings suggest that community health workers (CHWs) and local religious leaders would be an appropriate choice in this setting to train in basic mental healthcare. Traditional and primary care providers have reported feeling inadequately prepared to supply mental healthcare (Khoury et al., 2012) and often adhered to a protocol of sending severe cases to Haiti’s two distant psychiatric hospitals when the family could afford it (Hagaman et al., 2013). Following the 2010 earthquake, efforts to scale up mental health resources have called attention to chronic mental health needs throughout the country (Budosan & Bruno, 2011; de Ville de Goyet, Sarmiento, & Grunewald, 2011; Raviola et al., 2013; Rose, Hughes, Ali, & Jones, 2011). Budosan and Bruno (2011) found that establishing a referral system between the community and healthcare sector in Haiti was feasible by implementing a series of short (three-to-five day) mental health trainings. While this approach improved case finding, community level workers reported low motivation and low levels of perceived efficacy in care delivery, both of which are hallmarks of task sharing endeavours that have not succeeded (Kane, Gerretsen, Scherpbier, Dal Poz, & Dieleman, 2010). These challenges and outcomes highlight the need for ongoing professional support for non specialists participating in task sharing endeavours.

Objectives of the current study

The study objective was to implement and evaluate a culturally relevant task sharing training, meant to provide MHPSS services for mild to moderate mental distress in order to overcome the region’s shortage of mental healthcare professionals. Included in the study was a description of implementing two MHPSS task sharing training approaches: (1) a structured group training pilot of community health workers (CHWs) and (2) a structured group training plus an apprenticeship based supervision pilot. Both approaches were intended to train CHWs to identify cases of mental distress, provide basic MHPSS services and refer individuals requiring it to specialist services. The training and supervision approaches were evaluated in a process research approach2 using qualitative methods (Saunders, Evans, & Joshi, 2005).

Methods

Setting and context

The present project is part of mixed methods research examining perceptions, experiences, care seeking and supports available for persons with mental illness in Haiti’s Central Plateau (Hagaman et al., 2013; Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury, & Brewster, 2013; Kaiser et al., 2014; Keys et al., 2012; Khoury et al., 2012; Wagenaar, Hagaman, Kaiser, McLean, & Kohrt, 2012; Wagenaar et al., 2013).

The study team formed a partnership alongside a local nongovernmental organisation (NGO) interested in providing feasible forms of mental health support. Situated in a remote and rural region of the Central Plateau, the study location contained one basic health centre serving zones within a two hour walk. The clinic’s care focused mainly on mild to moderate health conditions, ranging from infectious diseases to maternal and child health. More severe cases were referred to one of three larger hospitals within a two hour drive. One physician, one nurse, two auxiliary nurses, one lab technician and one social worker served patients. Outreach in the form of mobile clinics occurred once every three months within each surrounding subregion. Only the physician and social worker had received any formal mental health training, which consisted of a standard psychiatric curriculum delivered in medical school and a post baccalaureate training programme, respectively. The training activities described below were implemented during May–June 2011, in partnership with a local NGO. Project activities were based in the communal section (roughly equivalent to a county) of Lahoye.. Apprenticeship trainees were followed-up in 2013.

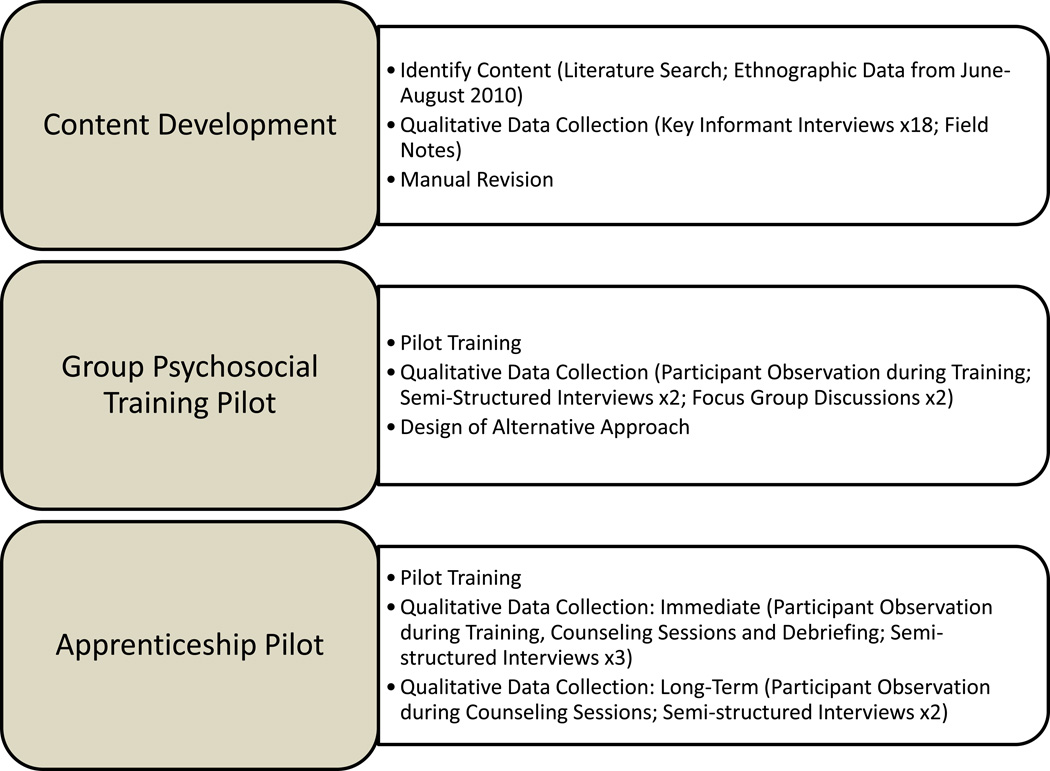

The authors conducted a multi-stage, transcultural training adaptation for a pilot mental health task sharing intervention. The process involved three phases: 1) review of the literature and qualitative data collection to adapt a MHPSS training; 2) implementation and qualitative process evaluation of a structured group pilot training; and 3) implementation and evaluation of an apprentice style pilot training (see Figure 1). Prior to implementing the study, the researchers had only planned for Phase 1 and Phase 2. However, based on the process research approach, the need for a modified training approach and supervision was identified. Therefore, Phase 3 was added to address trainees’ and researchers’ concerns about the limitations identified in Phase 2.

Figure 1.

Structure of training development: content development, group psychosocial training pilot, and apprenticeship pilot

Trilingual (Kreyòl, French, English) Haitian research assistants were recruited from the community to conduct onsite translation for interviews and focus group discussions, translate training materials and facilitate group trainings. One week of training familiarised research assistants with project aims and methods, techniques for providing literal translation and issues relating to ethics and confidentiality. Because many rural Haitians are illiterate, all participants provided verbal consent in Kreyòl or French. The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Emory University and the Haitian Ministry of Health.

Throughout the process, the study team used the terms tris (sadness), kè pa kontan (unhappy heart) and strès (stress) to refer to mild to moderate emotional distress because these local terms were more salient than psychiatric diagnostic terminology (Kaiser et al., 2014; Keys et al., 2012). After a more specific idiom of distress that captured psychological distress was identified, maladi kalkilasyon (thinking/calculating sickness) (Kaiser et al., 2014), this term was added.

Phase 1: Curriculum development

Following development of provisional modules, in-country qualitative data collection was conducted to adapt the modules using elements of a participant oriented approach (van der Veer & Francis, 2011). Eighteen key informant interviews were conducted with religious leaders, traditional healers, clinicians, teachers, municipal figures and other community leaders. These interviews relied on an open-ended, semi-structured format to allow for flexibility of questioning and responses. Topics addressed in the interviews included: local signs of mental distress, care seeking, problem solving and coping mechanisms. Participants were asked whether they would find an MHPSS training useful and, if so, what topics would be most valuable. Interviews were conducted in French or Kreyòl, facilitated by carefully trained trilingual research assistants and lasted between 30 minutes and one hour each. Responses were recorded in detailed, handwritten notes by members of the research team in English and then entered into a laptop computer on the same day for later thematic analysis (Bernard & Ryan, 2010). The research team met daily to discuss modification of questions in the interview guide, review each other’s notes, discuss emerging findings and identify important themes to be coded for analysis.

Phase 2: Structured training pilot

Qualitative post-training data collection was conducted to explore perceptions regarding the training and to identify areas for improvement. This included participant observation and semi-structured follow-up interviews with two of the trainees. Two team members observed the training and took detailed notes regarding participant engagement in training activities, interactions between participants and trainers and among participants, and topics covered.

Phase 3: Structured training plus supervised apprenticeship

Informed by data collected during phase two of the intervention, the study team adapted training materials to fit an apprenticeship-style approach. The apprenticeship was intended to address problems identified in the first training, in particular the low confidence among trainees to implement and integrate skills learned into daily practice. The new approach was to begin with a structured training similar to that provided to the entire group of CHWs. Prior to the Phase 3 training and apprenticeship, two focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted, one among local teachers and community leaders (n=7) and another among youth leaders (n=5) to inform this phase of adaptation. The purpose of further data collection was to gather insight into useful training modalities from individuals in the community with experience in teaching and conducting trainings. FGDs were facilitated by the team’s social worker, with a second team member present to take detailed, almost verbatim notes. These data were collected, recorded, and analysed similarly to the prior semi-structured interviews. Identified themes related to perceived usefulness of various training methodologies, preferred learning styles, logistics of hosting trainings, mechanisms of evaluation and general recommendations.

Qualitative data were collected throughout each apprenticeship and included semi-structured interviews with apprentices and participant observation during training, counselling sessions, and debriefing. Long term, follow-up data were collected two years later. The follow-up interviews focused on recent cases, including strategies for providing support and outcomes, and long term reflection on the training, including most and least useful components. In addition, the initial apprentice was shadowed, including observation of home visits with two current cases under his care. Detailed observation notes were taken regarding content of the conversation and visual cues (e.g. eye contact, facial expressions). With participants’ permission, interactions with the apprentice were audio recorded. All data were analysed to determine knowledge gained, satisfaction, confidence, intention to apply skills learned in daily practice and appropriateness of counselling provided.

Results

Phase 1: Content development

Process description

Based on the team’s prior qualitative research in Haiti’s Central Plateau during June-August 2010 (Kaiser et al., 2013; Kaiser et al., 2014; Keys et al., 2012; Khoury et al., 2012) and an extensive literature search, provisional training modules were developed by the study team, which included a Haitian clinical psychologist and a U.S. based cultural psychiatrist with experience in multiple LMICs. Modules drew upon mental health training manuals developed by mhGAP and Tiyatien Health3 for CHWs in India and Liberia (Gibson et al., 2010; WHO, 2010). Case studies taken from stories gathered during previous ethnographic data collection (Hagaman et al., 2013; Kaiser et al., 2014; Keys et al., 2012; Khoury et al., 2012) were used to place concepts and skills learned into local context, as well as to encourage discussion regarding identifying signs and symptoms of distress, suggesting coping mechanisms and deciding when to refer someone to seek professional care.

A body mapping exercise was developed for the first module, to aid participants in conceptualising a psychosocial model of mental health (IASC, 2007; Psychosocial Working Group, 2003). Body mapping is a research and training technique based on participatory research methods for cross-cultural populations and beneficiaries with limited education. Participants draw a figure and then indicate the location in or on the body where different aspects of distress are experienced. This approach is beneficial in cross-cultural settings to counter bias introduced by biomedical, psychiatric categories and symptoms. Local idioms of distress associated with psychosomatic complaints can be identified through body mapping exercises. This method had been utilised in the team’s prior work to understand how emotional experiences and cognitive processes are localised within various parts of the body in terms of idioms of distress (Keys et al., 2012) and was selected as a teaching modality that would have local relevance.

Key findings

Terminology for training

Signs and symptoms of distress included ‘weak limbs’ (fèb nan manm), ‘strange face’ (figi dwòl), ‘loss of good sense’ (pèdi bon sans), and ‘lack of motivation’ (mank motivasyon). ‘Thinking/calculating sickness’ (maladi kalkilasyon) and ‘thinking too much’ (reflechi twòp) are idioms marked by intense rumination, social isolation and prolonged sadness (Kaiser et al., 2014). These terms were all incorporated in the modules.

Selecting appropriate types of trainees

MHPSS provided by healthcare workers and other community supports was reported to be low by community members. Participants reported that CHWs did not talk to them about their feelings and suggested that it would be helpful to train them to listen better. The sacristan at the local Catholic Church noted that currently, ‘the local leaders do not have enough knowledge to support or talk to these individuals’. Such findings encouraged the team to include CHWs in the training, with a focus on basic communication skills such as supportive listening.

Content of training

In addition to a focus on listening skills, Phase 1 respondents called for training in coping mechanisms, including relaxation exercises. Suggested coping mechanisms included: reading the Bible, listening to music, sewing, going on a picnic and playing soccer. These were therefore incorporated into the training modules. The training also emphasised the need to identify coping mechanisms on an individual case basis, so that recommendations (including faith based activities) came from patients themselves and did not risk further stigmatisation or alienation. Confidentiality was additionally highlighted as an important training topic. Participants had reported that they do not often talk about their problems with neighbours and friends because they fear people will not practice confidentiality (kenbe yon bagay sekrè, lit. hold something secret): ‘The other women are not reliable and they gossip too much. If you ask another for help, they may be tempted to speak badly about you to other women in the community’ (Female farmer).

Of all the participants that were interviewed prior to the training, only one, a Deacon, mentioned that he ever referred individuals to a nearby psychologist. To raise awareness of the need for referrals, a module on this topic was included. Because there were no speciality serves available through the partner NGO, the study team worked with a different organisation, Zanmi Lasante4, to establish a referral system for individuals exhibiting the need for immediate care. The team was given tailored referral sheets to share with trainees to document the name, location, relevant history and mental health symptoms of any referred individual. Any care received was at no cost to the patient, and all travel related expenses were reimbursed by Zanmi Lasante.

Phase 2: Group MHPSS training pilot

Process description

The partner NGO hosted a pilot training. Trainees included fourteen CHWs currently working with the NGO, both ajan sante (community health workers) and promoteurs (community members who provide health education through song). They were assigned to participate by the local NGO and were initially selected for the training because they expressed a desire to participate. At the time of the training, CHWs were largely providing services for HIV/AIDS and cholera prevention.

The six modules were delivered by Haitian trainers in Kreyòl during a three day training period (see Box 1). An average of four hours per day were spent on training.

Box 1: Content of psychosocial training for community health workers.

Day 1

Developing a psychosocial model for mental health

-

1.

Participants are welcomed and introduced to members of the study team. An overview of the programme purpose and objectives is provided.

-

2.

A case study is presented to the group about a woman in the community who has experienced mental distress. Participants are asked to identify signs and symptoms of her distress and how they might help if she came to them for support. Designed to explore participants’ understanding and knowledge of mental health. To go beyond concepts of fou (psychosis), mental illnesses are defined more broadly as unhealthy thoughts, feelings and behaviours.

-

3.

Brainstorming activity helps participants to understand factors that contribute to mental distress and how members of the community experience suffering. Different domains affected by distress (e.g. head, heart, body, etc.) are listed on a flip chart. Used to facilitate understanding of a psychosocial model of mental health.

Recognising signs and symptoms of distress

-

4.

Brainstorming activity used to identify local signs and symptoms of mental distress. Responses are recorded on a flip chart. Participants are asked to identify the effects of mental illness on individuals and their families, including in regard to farm work, commerce, cooking and caring for the home and participation in community activities. Included also is a conversation on stigma and its impact on peoples’ wellbeing.

-

5.

Body mapping exercise used to illustrate concepts learned in previous brainstorming activity. Signs and symptoms of distress as experienced in various domains of ‘self’ are drawn on a handout. Participants break up into groups of three to complete the activity. Results are then shared with the group as a whole.

-

6.

Participants split up into groups and are asked to identify three things they learned from the session, two things they were still unclear about and one thing they felt they could teach to another. Designed to summarise the session and identify areas needing further discussion.

Day 2

Demonstrating active and supportive listening

-

1.

Participants reflect on Day 1 of the training. Major themes and messages are identified and concepts clarified as needed.

-

2.

Participants are introduced to the concept of supportive listening. In small groups, major steps to implementing supportive listening are identified and recorded on a flip chart. Groups then come together to compare findings.

-

3.

Role play is used to demonstrate the application of principles of supportive listening and to identify social and psychological benefits of applying supportive listening within a therapeutic environment. Participants are then split into groups of three to practice concepts learned.

Practising confidentiality when people come to you for help

-

4.

A trained local social worker speaks to participants on the concept of confidentiality and under what circumstances confidentiality may be broken. Participants are informed that if a person mentions wanting to inflict harm on himself or another person, they must inform a mental health professional.

-

5.

Case studies are used to explore ways that breach of confidentiality can negatively affect people suffering from mental health problems. Designed to emphasise the importance of patient/client privilege.

-

6.

Participants split up into groups and are asked to identify three things they learned from the session, two things they were still unclear about, and one thing they felt they could teach to another. Designed to summarise the session and identify areas needing further discussion.

Day 3

Managing and coping with mental distress

-

1.

Participants reflect on Day 2 of the training. Major themes and messages are identified and concepts clarified as needed.

-

2.

As a group, participants brainstorm different types of coping resources in the family and/or community. Coping mechanisms are divided according to mental, social, spiritual and physical strategies.

-

3.

Role play is used to illustrate how one might aid community members in identifying their own coping strategies so that they are relevant on a case-by-case basis. Participants are then split up into small groups to practice problem solving and scenarios where they help the individual to elicit certain help seeking behaviours and coping mechanisms.

Depending on referral strategies and resource networking

-

4.

Participants first discuss common pathways to care seeking in the community and factors that contribute to healthcare seeking, e.g. cost, trust, stigma, etc. Benefits and potential dangers of referring individuals to various sectors of care within the community are discussed.

-

5.

When to refer someone to a health professional is then discussed. Where to refer someone, depending on the circumstances, is then covered.

-

6.

A case study involving someone who is severely mentally distressed is used as an example to illustrate when and how to refer someone to a professional.

-

7.

A summary of the training is provided and participants are thanked for their time and participation.

At participants’ request, skills covered in the training were framed within a seven step procedure for providing MHPSS within the local context (see Box 2).

Box 2: Seven step approach to providing psychosocial support.

-

Ask questions to determine the emotional state of the client.

Participants identified questions such as: how are things going in your life right now?

-

Look for signs and symptoms of distress.

Local signs and symptoms that participants identified included: loss of weight, facial expressions like frowning or looking down, and not liking yourself.

-

Identify the source of the problem by asking for client’s history.

One way that a participant addressed this in a role play activity was by asking: what is causing you to feel sadness or stress?

-

Help the client to identify positive aspects of his or her life.

Participants might encourage client to: list activities they enjoy doing in their free time or things in their life that they are thankful for. Suggestions provided by community health workers during role play included: listening to the radio, playing soccer, going to church, and talking with friends.

-

Identify or help client to identify coping resources.

The participant might ask, for example: what do you like to do for fun? Activities identified by community members included: listening to the radio and playing dominoes.

-

Decide whether it is necessary to refer client to a professional.

Things that participants were encouraged to consider in their decision making process were: whether the person mentioned inflicting harm to another or to oneself (including threats of suicide).

-

End the conversation on a positive note.

In one role play scenario a participant ended a conversation by pointing out that his colleague had successfully suggested several coping mechanisms to try.

Key findings

Knowledge

After the training, participants reported having acquired knowledge on identifying signs and symptoms of mental distress, describing what it means to be a supportive listener, practising confidentiality and identifying coping methods. Few respondents were able to identify under what circumstances it is necessary to break confidentiality (e.g. danger to self or others). Instead, most respondents felt it was important to always maintain confidentiality, in order to gain trust.

Satisfaction

Participants reported overall satisfaction with the training. One female CHW reported, ‘Everything about the training went well. If I thought it wasn’t good or useful, I wouldn’t have left my house and trekked through the mud all the way to [the training centre]’. However, when asked what they had liked or disliked about the training, participants were hesitant to provide any criticism and would respond that they liked everything. This may be due to the fact that participants perceived trainers as experts ‘I don’t think I can tell you what to improve because you know more than I do’ (Female CHW).

Usefulness and preferred training method

A body map exercise was utilised to help participants visually illustrate the different domains of ‘self’ (e.g. head, soul) and to describe the psychological and emotional issues faced by community members within each of these domains (Karki, Kohrt, & Jordans, 2009; Keys et al., 2012). This exercise, role play, group discussions and case studies were all considered useful. Eliciting peer feedback during role play was challenging because participants perceived constructive criticism as losing face in front of the group. During role play, trainers repeatedly rephrased questions to avoid appearing to ask participants to criticise one of their co workers by suggesting ways to improve their response.

The use of a participatory method was also initially challenging because CHWs were uncomfortable providing their opinions in what was perceived as a formal teaching setting. In several unrelated trainings conducted by the host NGO, the team observed limited participation of trainees in proceedings. The training team mitigated this challenge, in part, by explaining their role to be more that of a facilitator and by emphasising that the participants were the ‘experts’ in this cultural context.

Confidence

Results were mixed regarding having the confidence to implement and integrate skills learned into daily practice. Prior to the training, CHWs expressed discomfort providing emotional support to community members: ‘I can help someone who has experienced mild issues or who has moderate distress (tonbe yon ti kras) [lit. ‘fallen some’], but not someone who has severe distress (tonbe anpil)’ [lit. ‘fallen a lot’] (Male CHW). Immediately following the training, several participants indicated that they would feel more able to succeed in helping someone who came to them with mental distress. Such responses illustrate increased confidence in providing assistance as a result of the training. However, several follow-up, semi-structured interviews revealed that trainees’ confidence to apply their new skills was actually low. These interviews also helped to identify elements of the training that participants thought could be improved to provide increased confidence. Respondents expressed concern that the trainings were not long enough to sufficiently teach skills needed to help those experiencing distress. One CHW stated that he would prefer longer trainings spread over time to reinforce ideas, as he was concerned about forgetting information learned in the training. Participants also expressed the desire for information to be presented in written form so that they could take the information home with them and concepts could be practised as needed over time. Other respondents reported that some aspects of the training remained unclear:

‘It was still somewhat unclear how to tell when a person is experiencing stress (strès) or anxiety (ankyete) without that person saying it. In this culture we know of stress, but we don’t really know what it does or how to tell if someone is stressed. This training was a good start, but I would like to have more information and strategies to help someone with stress’ (Male CHW).

A longer training period would have allowed for sufficient time to address signs and symptoms of local manifestations of distress and to practice engaging individuals with such symptoms.

Behaviour change and implementation

Observation and interviews following the training revealed that the intervention resulted in minimal changes in behaviour: no trainees provided accounts of implementing skills covered in the training in the two weeks following it. From limited qualitative data collected immediately following the training, the CHWs seemed to be anxious that the training would expose them not only to new skills but also to an entirely new role in the community - that of mental healthcare provider. Upon completion of the training, trainees were provided with a certificate of participation. However, participants expressed frustration that they were being asked to take on new and time intensive responsibilities without any monetary benefit. During a post training interview, a CHW provided an unsolicited detailed discussion of her own financial hardships and sources of distress related to family problems, which she viewed as a barrier to providing MHPSS services to others.

Phase 3: Apprenticeship pilot

Process description

Revisions of the structured training component included: differentiation of severe mental distress from mild distress, referral resources to link individuals to immediate care and clarifying circumstances in which to break confidentiality. Trainees were provided printed materials detailing training topics (e.g. signs and symptoms of distress, practising active listening, conveying confidentiality and building trust, identifying coping mechanisms and understanding health seeking behaviours). Such information was listed, along with referral strategies, so that they could easily draw on these resources in the future and link clients to appropriate caregivers.

Discussion, role play and case study vignettes were used to build up a basic level of knowledge and skill, as well as to assess understanding of the problems, causes and potential MHPSS within the local setting. Additionally, apprentices were exposed to the seven step approach to providing support within the context of a home visit (see Box 2). Following each role play, trainers and apprentices discussed how each member performed, how they could improve and key issues raised. Within this small motivated group, feedback became the cornerstone of success of this exercise.

After the structured training, the apprenticeship approach included one week of daily observation by a licensed counsellor conducting sessions with community members (approximately 1–2 session per day), followed by another week of supervised sessions where the trainee could practice new skills learned. Briefing and debriefing around these sessions were to facilitate learning and active problem solving. Furthermore, because experience showed that individuals were reticent to take on new, time intensive roles within the community without added monetary benefit, it was decided that only highly motivated individuals with adequate time availability would be recruited to participate in the second training pilot.

Three trainees were selected for the structured training plus apprenticeship pilot. Based on findings from Phase 2, we did not restrict participants only to health workers. Instead, any individuals who expressly demonstrated interest in MHPSS were included. This meant including one CHW participant from the group MHPSS training (Phase 2) who had expressed a desire for further skill building in the post training assessment. The two additional apprentices were a sacristan from the local Catholic church and a well-respected woman from the community. Despite not being CHWs, these individuals were selected because they were highly motivated, expressing interest in receiving training and members of the local community identified them as currently providing advice and help to others. Neither had received any former mental health-related training. Apprentices selected the frequency and timing of training sessions in order to fit within their schedules and daily tasks.

Following the classroom portion of the revised training, apprentices observed a licensed counsellor conducting counselling sessions with community members. These individuals were identified by our concurrent epidemiological survey (Wagenaar et al., 2012) as having depressive symptomology. These case visits included referral to local mental health professionals if the counsellor deemed it necessary. Individuals with severe mental distress, thoughts of suicide, or other needs requiring a psychologist or mental health physician were referred to Zanmi Lasante’s mental healthcare programme, with two facilities within a 30–45 minute drive from the community. Case visits progressed from the apprentice shadowing the licensed social worker on house visits, followed by debriefing and discussion, to the apprentice conducting home visits while being shadowed by the licensed social worker, again followed by debriefing and discussion. The apprentices observed approximately five one-hour counselling sessions over the course of one week before conducting their own supervised sessions. Follow-up debriefings included a discussion of what the apprentices did well and ways they could improve, as well as moments that were particularly challenging and how to address such situations in the future.

Key findings

Activities at follow-up

Two years after starting the apprenticeship process, all three trained apprentices were engaged in activities related to training, including providing mental health support and referring serious cases to professionals. Apprentices reported helping between 15 and 35 individuals in that time period, typically for relationship problems and ‘problems of life, Haitian problems’. They engaged in multiple visits with each individual, usually over a period of 1–3 months. Apprentices reported that their visits focused on helping to identify the source of problems, encouraging continued activity and goal setting, enabling individuals to focus on positive things in life and sources of support. There were no accounts of CHWs who underwent only the first group MHPSS training providing organised mental health support or referring individuals with serious mental disorders.

Service provision observation

Observation of apprentices in the field and feedback following MHPSS sessions showed that apprenticeship training was successful in promoting understanding of concepts related to providing mental health support. Participants seemed to understand the purpose of the sessions and how to integrate the concepts learned in the training into practice. One apprentice described his understanding of the counselling technique as follows: ‘at the beginning we tried to make nice with this person, make her feel comfortable being honest. In the middle, we underlined the problem. At the end, we tried to finish with a positive note’ (Male CHW). In conversation with the CHW, the client admitted to experiencing thoughts of suicide. The apprentice was successfully able to identify the source of distress and help the client identify positive aspects within her life, including coping resources. The apprentice referred her for professional care. During follow-up observations, the apprentice demonstrated active listening skills, a focus on encouraging individuals to identify coping resources and sources of hope and knowledge of when to refer individuals. These examples illustrate understanding of skills learned in the apprenticeship training, including how to maintain cohesion and flow within a MHPSS session, as well as when and where to refer cases of severe distress.

Satisfaction

Apprentices reported overall satisfaction with training goals and methods. They expressed a desire to train more individuals using the apprenticeship model. After completing the training, the male sacristan explained the importance of providing nearby regions with local counsellors:

‘I live here, I can help people nearby. If in another zone, however, that person cannot get to me. There needs to be someone there. You need to train and give a respected community leader this knowledge in every zone so everyone can have access to this support. If you train me, we can take one week in Lahoye and go train them too. We can help you train others.’

Apprentices reported that it was helpful to observe a trained professional conduct a counselling session in the field. In debriefing following a case visit, one participant said, ‘It has been helpful to see this. The more that you spoke with this person, the more comfortable they felt sharing with you’ (Male CHW). After observing the counsellor discuss coping mechanisms, the sacristan stated, ‘I really appreciate the positive method you used to let the lady know that there are a lot of things that she can do […] When you say that you are supposed to empower a person to solve their own problems, I didn’t understand it before, but I now understand.’ At the two year follow-up, apprentices noted that the training skills that they used most often were identifying signs and symptoms of distress and helping people to identify coping resources, such as community supports and engaging in activities.

Confidence

Not giving direct advice was a challenge for each apprentice to overcome, as witnessed both in role play and observation of the MHPSS sessions. A significant portion of initial training was spent practising how to handle situations where individuals were slow to suggest solutions on their own. Several role plays, involving feedback from both trainers and peers, as well as question and answer periods, helped the apprentices gain confidence and question posing skills. One apprentice, when asked by a supervisor what he thought he did well following a solo session, replied (with a smile), ‘I introduced myself and began the session well. I did best when the woman mentioned that it would be summer vacation soon, and she could save money then to go towards starting a business. She came up with her own solution.’ At two-year follow-up observation, there was a decrease in direct advice, with the apprentice solely asking questions and encouraging individuals to identify their own solutions.

When asked at follow-up for examples of cases that they would not have felt able to help prior to training, one apprentice named family problems, feelings of abandonment and hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. Another apprentice explained that he helped to intervene in a community disagreement and used his new skills to facilitate a resolution between neighbours. Additionally, all apprentices appear to have gained community recognition for their roles, reporting examples of individuals seeking them out for support. In other cases, they approached community members known to be suffering from mental distress or identified cases through typical encounters (in the case of the CHW).

Discussion

With the aim of contributing to identifying best practices for task sharing in humanitarian and LMIC settings, we described the development and implementation of two models for a task sharing mental health training in rural Haiti. After a group based, three day training, participants demonstrated increased knowledge; however, motivation and intention to apply concepts were lacking. Several participants expressed concern that they would forget concepts learned or did not fully understand how to implement skills taught. Additionally, no behavioural changes were observed or recounted following the initial pilot training. In contrast, an apprenticeship approach, which built upon a didactic-style training and included supportive supervision, demonstrated more positive outcomes. Given the various financial, logistical, and emotional barriers faced by these apprentices, we consider it particularly noteworthy that all three continued identifying, counselling, and referring community members at least two years after the training, and one former apprentice became an official volunteer for a large Haitian healthcare NGO as a psychosocial worker in a volunteer capacity. Factors that potentially explain these differences include training structure, recruitment of trainees and motivation to participate in the training in order to gain skills for future use.

Training structure

Group training may have limited benefit in practice because of the modality, while still important for knowledge gain. Teaching novel concepts within a classroom setting, especially concepts related to providing a public service, may be less effective for promoting skill building than coaching individuals through hands-on practice within the community. (Beidas, Koerner, Weingardt, & Kendall, 2011). While role play and other activities remain helpful teaching tools, they do not elicit the same level of practice and feedback compared to observed field activities. Moreover, post training supervision is one of the strongest predictors of behaviour change (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). Trainees in LMICs prefer exposure to real life experience when applying skills learned during trainings (Flisher et al., 2007).

The second pilot intervention provided practice-based learning within an apprenticeship model built on a structured foundational training. Our initial findings suggest that increased efforts to integrate elements of the apprenticeship approach, including active, participatory learning, ongoing supervision and on-site feedback are warranted. This is consistent with recommendations that trainings should be active and practical, incorporating behavioural rehearsal (Herschell et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2011). The supervision in the apprenticeship training model that enabled bidirectional collaboration and assurance of back-up support may be responsible for observed behaviour change following the intervention. Bidirectional teaching that treats trainees as engaged, rather than passive, participants, as well as supervision, is considered critical (Beidas et al., 2011). Such bidirectional collaboration is also an important predictor of effective interventions (Forman, Olin, Hoagwood, Crowe, & Saka, 2009), with assurance of a back-up system of support shown to be a key ingredient in some successful task sharing interventions (Kane et al., 2010). Future research should explore the impact of different durations of supervision processes in promoting capacity and motivation to provide MHPSS services.

Identifying appropriate trainees

One of the reasons that this apprenticeship model may have been successful was because only motivated, community identified volunteers were trained. They were already working to provide emotional support within the community and had expressed interest in learning additional skills. It is often assumed that training of individuals who self-select into intervention programmes is good practice, despite evaluations showing no significant differences in empathy and psychological mindedness of volunteer versus non volunteer trainees (Compton, Broussard, Hankerson-Dyson, Krishan, & Stewart-Hutto, 2011). Research related to the effectiveness of programmes that recruit on a volunteer basis is further warranted. Motivation, anticipation of being valued by the community and assurance of back-up support are important factors, as task sharing personnel may already be overburdened with multiple community health demands (Kane et al., 2010; Maes, Kohrt, & Closser, 2010). In this case, task sharing runs the risk of becoming ‘task dumping.’

Our team may have mistakenly concluded that CHWs would be the most appropriate group for this training because of their health related experience, mobility and regular access to individuals in their homes. However, this failed to account for structural barriers that may have prevented them from effectively incorporating new MHPSS skills into their daily activities. Such barriers include monetary compensation and available time and resources. Again, CHWs living in low resource settings, especially post disaster settings, are often overburdened with numerous tasks (Maes, Shifferaw, Hadley, & Tesfaye, 2011).

Following the group training, CHWs requested additional pay for implementing new skills learned. Although the CHWs in this training did receive a salary for their employment, we were asking them to take on additional responsibilities without additional compensation. It is worth considering whether this was a fair expectation. CHWs and other mid-level healthcare providers are often overburdened with day-to-day responsibilities of caregiving, coupled with their own economic stress (Maes et al., 2010; Maes et al., 2011). On a global scale, there is general reluctance by donors to direct funds toward creating healthcare jobs in low income countries, despite critical shortages in staffing (Ooms, van Damme, & Temmerman, 2007). As a result, cheap or volunteer labour has become the norm in many LMICs. Although the apprentices were not paid, our findings suggest that appropriate compensation should accompany the expectation that CHWs take on new skills and responsibilities.

In addition to increased wages, an added incentive, such as a recognised certification for the training, is important. Several participants conveyed the desire for concrete ‘proof’ that they had received new skills. Although this was a pilot training, task sharing initiatives may be more effective if care providers can be formally recognised by national or community wide education organisations (WHO, 2008). Certification has also been shown to improve overall effectiveness of health-related trainings (Necochea, 2006; WHO, 2003). Furthermore, Farmer and colleagues argue that CHWs should be incorporated into the public sector, which would have the dual benefit of ensuring government recognition and strengthening public health systems (Mukherjee & Eustache, 2007; Public Broadcasting System, 2009).

Additionally, it is also important to consider whether recruits for task sharing trainings within global mental healthcare are having their own emotional and mental health needs addressed. During post training interviews, participants cited family and financial problems and related personal emotional distress as barriers to engaging in MHPSS services for others. Petersen, Ssebunnya, Bhana, and Baillie (2011) emphasise the importance of support and supervision for healthcare workers exhibiting stress as part of care delivery within task sharing initiatives.

Strengths and limitations

This was a pilot intervention with a small sample size nested within the particular social and cultural milieu of one Haitian community. The evaluation of the training reflected in this analysis is purely qualitative and therefore lacks standardised measures of knowledge acquisition. Ideally, the optimal measure of effectiveness would have been an evaluation of patient outcomes through both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The supervisor trainer for both studies was an American social worker who did not speak the local language. Though a Haitian psychologist was originally intended to fill this role, she unexpectedly withdrew from field participation prior to training. For the structured group training, several participants declined to be interviewed following completion of the training due to issues related to lack of time and resources and reported disinterest. Our present project also does not formally compare the two approaches. More rigorous methods are needed to fully evaluate the apprenticeship approach and other training models. In particular, anonymous feedback approaches would have been a useful complement to in-depth interviews.

Another limitation is that at the time of the study, the CHW training modules for mhGAP were not available, and this training relied upon modified versions of mhGAP-IG. Finally, whereas this approach involved task sharing of mental health services to CHWs, a collaborative care model in which health workers at multiple levels were trained would have been preferable and would have increased the likelihood of appropriate division of responsibilities. Overburdening community health workers without adequate access to higher levels of expertise is a disincentive to appropriate provision of care. Another limitation is that this study only employed selected elements of participant oriented approaches as outlined by van der Veer and Francis (2011). Implementing the process with exclusive allegiance to participant oriented methodology may have produced different qualitative outcomes.

On the other hand, this project had several strengths. The training was developed alongside community members and research assistants within a participatory format. Qualitative methodologies allowed the team to explore perceptions and behaviour in greater depth and to uncover context specific challenges to providing MHPSS services. In the case of small samples, qualitative evaluation is preferable to quantitative measures, as the former can provide detailed information of knowledge gained and how to improve training content and structure. Our study incorporated long term follow-up data attesting to the utility of the apprenticeship model. This is important, given that few studies have documented sustained changes in practice beyond six months following training (Flisher et al., 2007).

Conclusions

Qualitative process assessment of two training models that were iteratively designed and implemented supports use of a culturally adapted apprenticeship model with supportive supervision. More studies that evaluate methods to recruit, train and supervise mid-level mental health workers in low resource settings are needed, especially those that utilise rigorous randomisation methods and long term follow-up. Without rigorous evaluation of trainings, it is difficult to determine if interventions succeed or fail because of the intervention content or because of the approaches used to train practitioners.

Going forward, it will also be important to assure that community based training activities are embedded within approaches to build multi-layered systems of care (Patel & Thornicroft, 2009). CHWs and other non specialists involved in mental healthcare provision serve as an important link between community members and healthcare providers, especially when professionals are in short supply. For post conflict, post disaster and poverty stricken populations, there is a crucial need to identify training strategies for CHWs with the greatest likelihood of improving individual and community wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of field research assistants Wilfrid Jean, Adner Louis and Alexis Ronel. We also thank Melissa Etheart, Michael Nguyen, Lydia Odenat and Rose Merline Pierre Louis for their assistance in the development and implementation of the training. We are grateful to Tiyatien Health in Liberia for their allowing us to use their depression training manual for CHWs as a guide for the development of our psychosocial training. We also thank the international healthcare organization Partners in Health and its Haitian sister organization Zanmi Lasante for their partnership throughout this project and for accepting patient referrals. This work was supported by Emory University's Global Health Institute Multidisciplinary Team Field Scholars Award, Emory University’s Global Field Experience Award and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (grant # 0234618 for Bonnie N. Kaiser) and Dissertation Development Research Improvement Grant (for Bonnie N. Kaiser). The senior author (Brandon A. Kohrt) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Reducing Barriers to Mental Health Task Sharing (K01 MH104310-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

We employ the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines to operationalise mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) to “describe any type of local or outside support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental disorder,” (IASC, 2007, p. 1). The term psychosocial is defined according to The Psychosocial Working Group as “well-being of an individual... with respect to three core domains: human capacity, social ecology and culture & values. These domains map in turn the human, social and cultural capital available to people responding to the challenges of prevailing events and conditions,” (The Psychosocial Working Group, Centre for International Health Studies Queen Margaret University College, 2003, p. 2).

Process evaluation research refers to methods and theories employed to monitor and document the implementation of intervention programs. Process evaluation research is used to elucidate how intervention elements and pathways contribute to intervention outcomes (Saunders, Evans, & Joshi, 2005). Qualitative methods are commonly used to document intervention processes that are not amenable to categorical or other forms of quantitative reporting.

Unpublished training manual provided by Tiyatien Health and used with permission. Tiyatien Health has been renamed as Last Mile Health (www.lastmilehealth.org).

Zanmi Lasante is a nongovernmental healthcare provider in Haiti and a sister organization of Partners in Health (www.pih.org/country/haiti/about)

Contributor Information

Kristen E McLean, Department of Anthropology at Yale University.

Bonnie N Kaiser, Department of Anthropology at Emory University.

Ashley K Hagaman, Department of Global Health, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, at Arizona State University.

Bradley H Wagenaar, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, at the University of Washington.

Tatiana P Therosme, She is a member of the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Team at Zanmi Lasante/Partners in Health in Haiti’s Central Plateau.

Brandon A Kohrt, He is currently an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Global Health, and Cultural Anthropology at the Duke Global Health Institute and Department of Psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine.

References

- Baingana F, Mangen PO. Scaling up of mental health and trauma support among war affected communities in northern Uganda: lessons learned. Intervention. 2011;9(3):291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin Psychol. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Koerner K, Weingardt KR, Kendall PC. Training research: practical recommendations for maximum impact. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:223–237. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0338-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. Los Angeles: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bijoux L. Evolution of concepts and interventions in mental health in Haiti [in French] Revue Haitienne de la Santé Mentale. 2010;1:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Budosan B. Mental health training of primary healthcare workers: case reports from Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Jordan. Intervention. 2011;9(2):125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Budosan B, Bruno RF. Strategy for providing integrated mental health/psychosocial support in post earthquake Haiti. Intervention. 2011;9(3):225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Country Management Unit. Social resilience and state fragility in Haiti: a country social analysis. World Bank. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Broussard B, Hankerson-Dyson D, Krishan S, Stewart-Hutto T. Do empathy and psychological mindedness affect police officers' decision to enter crisis intervention team training? Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:632–638. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.6.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ville de Goyet C, Sarmiento JP, Grunewald F. Health responses to the earthquake in Haiti, January 2010: lessons to be learned for the next sudden-onset disaster. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Lund C, Funk M, Banda M, Bhana A, Doku V, Green A. Mental health policy development and implementation in four African countries. J Health Psychol. 2007;12:505–516. doi: 10.1177/1359105307076237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S, Olin S, Hoagwood K, Crowe M, Saka N. Evidence-based interventions in schools: developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health. 2009;1:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson K, Kermode M, Devine A, Raja S, Sunder U, Mannarath SC. An introduction to mental health – A facilitator's manual for training community health workers in India. Melbourne: Nossal Institute for Global Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hagaman AK, Wagenaar BH, McLean KE, Kaiser BN, Winskell K, Kohrt BA. Suicide in rural Haiti: clinical and community perceptions of prevalence, etiology, and prevention. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva: Inter-Agency Standing Committee; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser BN, Kohrt BA, Keys HM, Khoury NM, Brewster AR. Strategies for assessing mental health in Haiti: local instrument development and transcultural translation. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50:532–558. doi: 10.1177/1363461513502697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser BN, McLean KE, Kohrt BA, Hagaman AK, Wagenaar BH, Khoury NM, Keys HM. Reflechi twop--thinking too much: description of a cultural syndrome in Haiti's Central Plateau. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2014;38:448–472. doi: 10.1007/s11013-014-9380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, Scheffler RM. Human resources for mental healthcare: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. 2011;378:1654–1663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane SS, Gerretsen B, Scherpbier R, Dal Poz M, Dieleman M. A realist synthesis of randomised control trials involving use of community health workers for delivering child health interventions in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:286. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki R, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD. Child Led Indicators: pilot testing a child participation tool for psychosocial support programmes for former child soldiers in Nepal. Intervention. 2009;7:92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Keys HM, Kaiser BN, Kohrt BA, Khoury NM, Brewster AR. Idioms of distress, ethnopsychology, and the clinical encounter in Haiti's Central Plateau. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury NM, Kaiser BN, Keys HM, Brewster AR, Kohrt BA. Explanatory models and mental health treatment: is Vodou an obstacle to psychiatric treatment in rural Haiti? Cult Med Psychiatry. 2012;36:514–534. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes KC, Kohrt BA, Closser S. Culture, status and context in community health worker pay: pitfalls and opportunities for policy research. A commentary on Glenton et al. (2010) Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1375–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.020. discussion 1379–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes KC, Shifferaw S, Hadley C, Tesfaye F. Volunteer home-based HIV/AIDS care and food crisis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: sustainability in the face of chronic food insecurity. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26:43–52. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NL. Haitian ethnomedical systems and biomedical practitioners: directions for clinicians. J Transcult Nurs. 2000;11:204–211. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne D, Aylott H, Fitzpatrick H, Ellis MV. How Does Clinical Supervision Work? Using a "Best Evidence Synthesis" Approach to Construct a Basic Model of Supervision. The Clinical Supervisor. 2008;27:170–190. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee JS, Eustache FE. Community health workers as a cornerstone for integrating HIV and primary healthcare. AIDS Care. 2007;19(Suppl 1):S73–S82. doi: 10.1080/09540120601114485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Bolton P, Jordans MJ, Rahman A, Bass J, Verdeli H. Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: an apprenticeship model for training local providers. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necochea E. Building stronger human resources for health through licensure, certification and accreditation. Chapel Hill: The Capcity Project; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms G, van Damme W, Temmerman M. Medicines without doctors: why the Global Fund must fund salaries of health workers to expand AIDS treatment. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Haiti: profile of the health services system. Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Thornicroft G. Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: PLoS Medicine Series. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Broadcasting System. Africa: house calls and healthcare. 2009 http://www.pbs.org/now/shows/537/index.html.

- Perez-Sales P, Fernandez-Liria A, Baingana F, Ventevogel P. Integrating mental health into existing systems of care during and after complex humanitarian emergencies: rethinking the experience. Intervention. 2011;9:345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Ssebunnya J, Bhana A, Baillie K. Lessons from case studies of integrating mental health into primary healthcare in South Africa and Uganda. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial Working Group. Psychosocial Intervention in Complex Emergencies: A Framework for Practice. Edinburgh: Queen Margaret University College; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Raviola G, Eustache E, Oswald C, Belkin GS. Mental health response in Haiti in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake: A case study for building long-term solutions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2012;20:68–77. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.652877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviola G, Severe J, Therosme T, Oswald C, Belkin G, Eustache E. The 2010 Haiti earthquake response. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36:431–450. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose N, Hughes P, Ali S, Jones L. Integrating mental health into primary healthcare settings after an emergency: lessons from Haiti. Intervention. 2011;9:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a Process-Evaluation Plan for Assessing Health Promotion Program Implementation: A How-To Guide. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(2):134–147. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370:878–889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasundram D. Disaster mental health in Sri Lanka. In: Diaz J, Murthy R, Lakshminarayana, editors. Advances in disaster mental health and psychological support. Delhi: VHAI Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- van der Veer G, Francis FT. Field based training for mental health workers, community workers, psychosocial workers and counselors: a participant-oriented approach. Intervention. 2011;9:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Meera SM, Pian J, Patel V. Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD009149. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009149.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventevogel P, van de Put W, Faiz H, van Mierlo B, Siddiqi M, Komproe IH. Improving access to mental healthcare and psychosocial support within a fragile context: a case study from Afghanistan. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar BH, Hagaman AK, Kaiser BN, McLean KE, Kohrt BA. Depression, suicidal ideation, and associated factors: a cross-sectional study in rural Haiti. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar BH, Kohrt BA, Hagaman AK, McLean KE, Kaiser BN. Determinants of care seeking for mental health problems in rural Haiti: culture, cost, or competency. Psych Serv. 2013 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology. Cross-national comparisons of mental disorders. B World Health Organ. 2000;78:413–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Quality and accreditation in healthcare services: a global review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Disease control priorities related to mental, neurological, developmental and substance abuse disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specified health settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Le système santé mentale en Haïti: rapport d’évaluation du système de Santé mentale en Haïti a l’aide de l’instrument d’evaluation conçu par L’Organization Mondiale de la Santé Mentale (OMS). Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population, Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, Organisation Panamé ricaine de la Santé. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, & Wonca. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]