Abstract

We describe a simple method for detection of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infection in anophelines using a triplex TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (18S rRNA). We tested the assay on Anopheles darlingi and Anopheles stephensi colony mosquitoes fed with Plasmodium-infected blood meals and in duplicate on field collected An. darlingi. We compared the real-time PCR results of colony-infected and field collected An. darlingi, separately, to a conventional PCR method. We determined that a cytochrome b-PCR method was only 3.33% as sensitive and 93.38% as specific as our real-time PCR assay with field-collected samples. We demonstrate that this assay is sensitive, specific and reproducible.

Keywords: Anopheles, Plasmodium, TaqMan, real-time PCR

Here we describe a reliable, sensitive and specific real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol to detect the two most common species of Plasmodium (vivax and falciparum) in Anopheles mosquito vector DNA, optimised with TaqMan reagents. It is essential to accurately identify mosquito vectors and their Plasmodium species infection status to calculate the entomological inoculation rate for monitoring and evaluating malaria transmission levels. A comparison was made between the commonly used cytochrome b PCR-based (Cytb-PCR) method for detecting P. falciparum and P. vivax (Hasan et al. 2009) infections and our real-time PCR method.

Colony Anopheles darlingi (Moreno et al. 2014) and Anopheles stephensi (provided by F Li and JM Vinetz, University of California, San Diego) were fed to repletion, using a membrane feeder, on P. vivax or P. falciparum-infected blood, respectively, then euthanised 14 days post-blood meal. Individual mosquito heads and thoraces were extracted manually or with a QIAcube using the DNeasy® Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany). DNA concentration of each extraction was determined using a Qubit® 2.0 fluorometer with the Qubit® dsDNA high sensitivity assay (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Plasmodium infection was detected with real-time PCR of the small subunit of the 18S rRNA gene, using a monoplex or triplex TaqMan assay (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific). These assays employed primers designed elsewhere (Rougemont et al. 2004, Shokoples et al. 2009, Diallo et al. 2012) with modified Plasmodium species-specific forward primers and probes. Modified primers were optimised for TaqMan assays using Primer Express® software v.3.0.1 (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plasmodium detection was achieved using genus specific primers and probe (Plasmo1-F: GTTAAGGGAGTGAAGACGATCAGA; Plasmo2-R: AACCCAAAGACTTTGATTTCTCATAA; Plasprobe: FAM-TCGTAATCTTAACCATAAAC-MGBNFQ) (Rougemont et al. 2004, Shokoples et al. 2009). P. vivax or P. falciparum species determination was achieved using forward primers and probes nested within the genus-specific product (Falc-F: GACTAGGTGTTGGATGAAAGTGTTAAA; Falciprobe: VIC-TGAAGGAAGCAATCTAAAAGTCACCTCGAAAGA-QSY; Vivax-F: GACTAGGCTTTGGATGAAAGATTTTAA; Vivaxprobe: NED-ATAAACTCCGAAGAGAAAA-MGBNFQ). Primers and probes were synthesised by Life Technologies. Each PCR reaction occurred in 20 µL containing 1x PerfeCTa qPCR ToughMix, Uracil N-glycosylase (UNG), ROX (Quanta Biosciences, USA), 0.3 µM of each primer, 0.1 µM of each probe and genomic DNA. Cycling conditions for both the monoplex and triplex assays included a 5 min UNG-activation hold at 45ºC and a denaturation step for 2 min at 95ºC, followed by 50 cycles of 95ºC denaturation for 15 s and 60ºC annealing/elongation for 1 min.

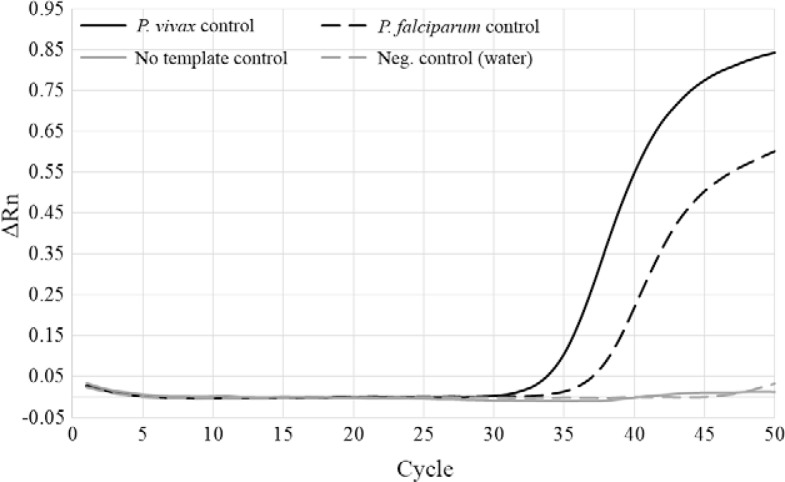

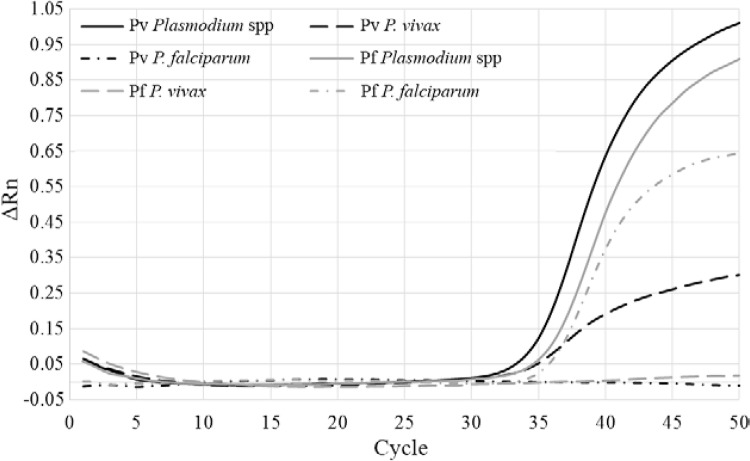

DNA pools of five mosquitoes were made using equal amounts of gDNA (ng) per mosquito. Mosquito DNA pools were tested initially with a monoplex assay for Plasmodium spp detection using only Plasmodium genus-specific primers and probe. For this assay, up to 15 ng of gDNA was used per reaction with a maximum volume of 8.6 µL. Controls consisted of water as a negative control, a no-template control using gDNA from uninfected, colony An. darlingi and a positive control of 1,000X diluted MR4 MRA-102G (reagent obtained through the MR4 as part of the BEI Resources Repository, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health: P. falciparum genomic DNA from P. falciparum 3D7, MRA-102G) (Rosario 1981, Walliker et al. 1987). Amplification began at approximately cycle 35 (Plasmodium spp range 32-34, P. vivax range 32-36 and P. falciparum range 34-38), with a cut-off of 50 cycles to define Plasmodium positive samples. Plasmodium spp positive An. darlingi and An. stephensi were then tested using the triplex assay to confirm infection status and verify the specificity of the assay by determining the Plasmodium species. In these individual triplex reactions, up to 15 ng of gDNA was used per reaction with a maximum volume of 7 µL. Cycling conditions were the same as for the monoplex assay.

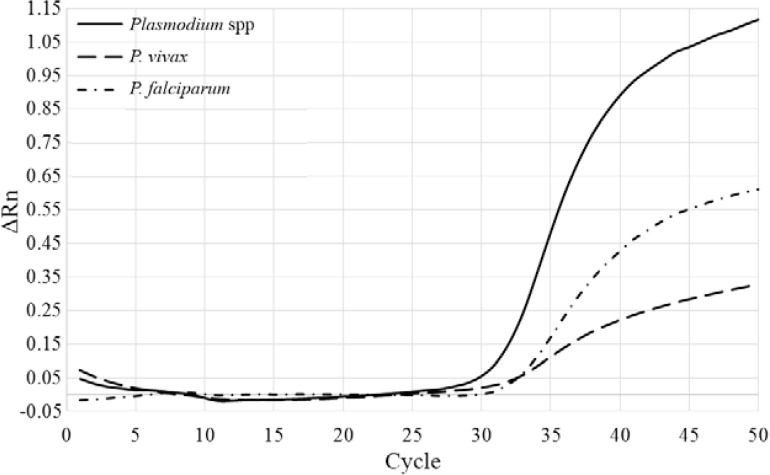

Previous studies (Rao et al. 2009, Sandeu et al. 2012, Marie et al. 2013, Ngo et al. 2014) have developed real-time PCR assays to detect Plasmodium infections in mosquito vectors, but none in the major Neotropical vector An. darlingi. Our motivation for developing this assay was to reliably detect Plasmodium-infected field-caught mosquitoes in malaria endemic regions of Latin America to incriminate anopheline vectors. Therefore, we tested the monoplex assay on pools of five field-caught An. darlingi mosquitoes from localities near Iquitos, Peru, in duplicate. In all cases, pools identified as positive in monoplex assay were positive in both replicates. Individual mosquitoes from each of the positive pools were tested with the triplex assay to determine infection status and corresponding Plasmodium species. At least one Plasmodium-positive An. darlingi was identified in each positive pool. Throughout the course of development and analyses, this assay proved very reliable under a number of different circumstances: (i) individual Plasmodium positive mosquitoes were identified in pools of DNA from five mosquitoes via monoplex assay (Fig. 1) and verified in individual mosquito triplex assay, (ii) positive controls were accurately and reliably identified in triplex assay (Fig. 2), (iii) mixed infections were identified in some mosquito samples (Fig. 3) and, finally, (iv) Plasmodium-positive mosquitoes that measured as low as < 0.5 ng/µL in Qubit® assay amplified and showed infection in the triplex assay.

Fig. 1. : real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification plot of a monoplex Plasmodium spp assay. The four quantitative PCR controls are shown: Plasmodium vivax infected Anopheles darlingi (black, solid line), Plasmodium falciparum infected Anopheles stephensi (black, dashed line), uninfected An. darlingi (no template control) (grey, solid line) and water (negative control) (grey, dashed line). ΔRn: baseline corrected normalised fluorescence.

Fig. 2. : real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification plot of a triplex Plasmodium spp assay. The two quantitative PCR positive controls are shown: Plasmodium vivax infected Anopheles darlingi (black lines) (solid line: Plasmodium spp positive; dashed line: P. vivax species positive; dashed/dotted line: Plasmodium falciparum negative) and P. falciparum infected Anopheles stephensi (grey lines) (solid line: Plasmodium spp positive; dashed line: P. vivax negative; dashed/dotted line: P. falciparum positive). ΔRn: baseline corrected normalised fluorescence.

Fig. 3. : real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification plot of a triplex Plasmodium spp assay showing a sample with a mixed Plasmodium vivax/Plasmodium falciparum infection (solid line: Plasmodium spp positive; dashed line: P. vivax positive; dashed/dotted line: P. falciparum positive). ΔRn: baseline corrected normalised fluorescence.

The results from real-time PCR Plasmodium detection were compared with the results of the Cytb-PCR method for detection of Plasmodium, which amplifies the Plasmodium Cytb gene. This PCR method was carried out according to Hasan et al. (2009) and infection was determined through visualisation of PCR product on agarose gel. To compare the results from the two assays, sensitivity and specificity calculations, Cohen’s kappa (κ) (for concordance) and McNemar’s test (for discordance) were implemented. In these comparisons, the Cytb-PCR results were compared to our assay’s results for two important reasons. First, while testing samples with the Cytb-PCR protocol, we ran into problems that suggested the results could not be replicated, such as nonspecific binding (laddering of the PCR product on agarose gel) and inconsistency of results between our laboratory and our collaborating International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research laboratory in Iquitos. Samples with laddering included one band that corresponds to the correct PCR product size, but there were also samples that appeared positive without the laddering effect. Second, multiple reports have shown real-time PCR detection of Plasmodium is much more sensitive than conventional PCR-based methods and provide faster, less time-consuming results with a reduced risk of contamination (Rougemont et al. 2004, Shokoples et al. 2009, Marie et al. 2013, Lau et al. 2015).

Sensitivity, or the ability of an assay to correctly determine whether a sample is truly positive, is calculated by dividing the number of true positives (TP) (both assays agree that a sample is positive) by the sum of the TPs and the false negatives (FN):

|

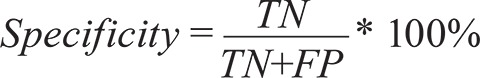

In this case, FNs are those samples positive by real-time PCR, but negative by Cytb-PCR. Specificity is the ability of an assay to correctly determine whether a sample is truly negative. This is calculated by dividing the number of true negatives (TN) (both assays agree that a sample is negative) by the sum of the TNs and the false positives (FP):

|

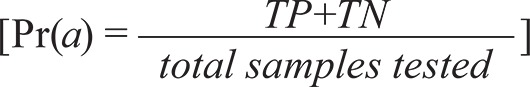

FPs are samples negative by real-time PCR assay but positive by Cytb-PCR assay (Gerstman 2008). Cohen’s κ, used to measure agreement, determines at what percentage of samples the results from the two assays agree, correcting for random chance. κ ranges between -1, complete disagreement and 1, complete agreement and is calculated by first determining the percentage of the samples with results that agree between the two assays:

|

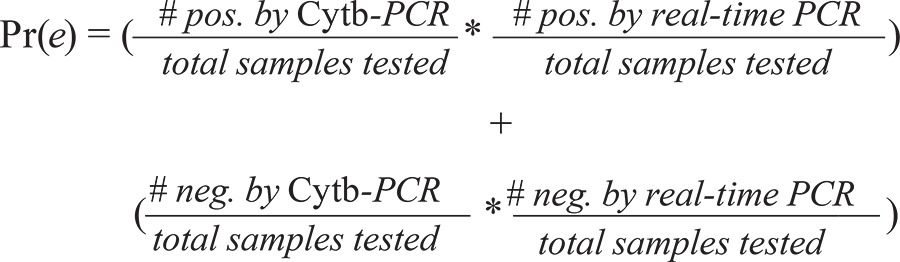

Next, the probability of random chance agreement is calculated by the product of the percentages of samples that were considered positive by each assay, added to the product of the percentages of samples that were considered negative by each assay:

|

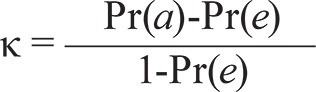

Finally, κ is calculated (Cohen 1960) by

|

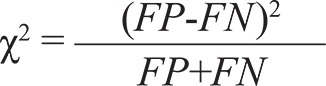

The test statistic for McNemar’s test for discordance is calculated as

|

and follows a chi-squared distribution with one degree of freedom (McNemar 1947).

When we compared our real-time assay to the Cytb-PCR assay using laboratory-infected mosquitoes, we found few differences. The Cytb-PCR assay was 85% as sensitive and 82.50% as specific as our real-time PCR assay and showed substantial agreement (κ = 0.68). In addition, McNemar’s test showed no significant discordance between assays (χ2 = 0.077; p > 0.5) (Table I). However, in comparisons using field-collected An. darlingi, Cytb-PCR is 3.33% as sensitive and 93.38% as specific as our real-time PCR assay (Table II). Additionally, the Cytb-PCR protocol neither agrees nor disagrees with our assay, after accounting for random chance (κ = -0.04) and is not significantly discordant from our real-time PCR assay (χ2 = 1.653; p > 0.1), due to the large number of truly negative samples tested (Table II). In Latin America, the percentage of Plasmodium-infected anopheline vectors varies greatly and is highly dependent upon vector, season, host availability and location (da Silva-Nunes et al. 2012). The comparisons between these assays represent a real-world scenario, as would be encountered by vector biologists testing field-collected samples, in addition to comparing results of known infected mosquitoes from laboratory colonies (as above).

TABLE I. Comparison of results from the cytochrome b-polymerase chain reaction (Cytb-PCR) and real-time PCR Plasmodium detection assays with laboratory infected Anopheles darlingi and Anopheles stephensi .

| Real-time PCR positive (n) | Real-time PCR negative (n) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytb-PCR positive | 34 | 7 | 85 | 82.50 |

| Cytb-PCR negative | 6 | 33 | - | - |

Cohen’s kappa = 0.68; McNemar’s test χ2 = 0.077, p > 0.5.

TABLE II. Comparison of results from the cytochrome b-polymerase chain reaction (Cytb-PCR) and real-time PCR Plasmodium detection assays using field-caught Anopheles darlingi .

| Real-time PCR positive (n) | Real-time PCR negative (n) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytb-PCR positive | 1 | 20 | 3.33 | 93.38 |

| Cytb-PCR negative | 29 | 282 | - | - |

Cohen’s kappa = -0.04; McNemar’s test χ2 =1.653, p > 0.1.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the assays we describe are sensitive, specific and reproducible alternative to the Cytb-PCR-based detection of P. vivax and P. falciparum in field collected Anopheles samples.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To Carlos Tong (Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Peru), for providing P. vivax infected An. darlingi, and to Dr Fengwu Li (Division of Infectious Diseases, UCSD), for providing P. falciparum infected An. stephensi.

Funding Statement

Financial support: NIH [R01 AI110112 (to JEC), U19 AI089681 (to JMV)] SAB and WL contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Financial support: NIH [R01 AI110112 (to JEC), U19 AI089681 (to JMV)] SAB and WL contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Nunes M, Moreno M, Conn JE, Gamboa D, Abeles S, Vinetz JM, Ferreira MU. Amazonian malaria: asymptomatic human reservoirs, diagnostic challenges, environmentally driven changes in mosquito vector populations and the mandate for sustainable control strategies. Acta Trop. 2012;12:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo A, Ndam NT, Moussiliou A, Santos S, Ndonky A, Borderon M, Oliveau S, Lalou R, Le Hesran JY. Asymptomatic carriage of Plasmodium in urban Dakar: the risk of malaria should not be underestimated. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstman BB. Basic biostatistics - Statistics for public health practice. Jones and Bartlett Publishers; Sudbury: 2008. 648 [Google Scholar]

- Hasan AU, Suguri S, Sattabongkot J, Fujimoto C, Amakawa M, Harada M, Ohmae H. Implementation of a novel PCR based method for detecting malaria parasites from naturally infected mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. 182Malar J. 2009;8 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau YL, Lai MY, Anthony CN, Chang PY, Palaeya V, Fong MY, Mahmud R. Comparison of three molecular methods for the detection and speciation of five human Plasmodium species. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:28–33. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie A, Boissiere A, Tsapi MT, Poinsignon A, Awono-Ambene PH, Morlais I, Remoue F, Cornelie S. Evaluation of a real-time quantitative PCR to measure the wild Plasmodium falciparum infectivity rate in salivary glands of Anopheles gambiae. 224Malar J. 2013;12 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Tong C, Guzman M, Chuquiyauri R, Llanos-Cuentas A, Rodriguez H, Gamboa D, Meister S, Winzeler EA, Maguina P, Conn JE, Vinetz JM. Infection of laboratory-colonized Anopheles darlingi mosquitoes by Plasmodium vivax. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:612–616. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo CT, Dubois G, Sinou V, Parzy D, Le HQ, Harbach RE, Manguin S. Diversity of Anopheles mosquitoes in Binh Phuoc and Dak Nong provinces of Vietnam and their relation to disease. 316Parasit Vectors. 2014;7 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RU, Huang Y, Bockarie MJ, Susapu M, Laney SJ, Weil GJ. A qPCR-based multiplex assay for the detection of Wuchereria bancrofti, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax DNA. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario V. Cloning of naturally occurring mixed infections of malaria parasites. Science. 1981;212:1037–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.7015505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougemont M, Van Saanen M, Sahli R, Hinrikson HP, Bille J, Jaton K. Detection of four Plasmodium species in blood from humans by 18S rRNA gene subunit-based and species-specific real-time PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5636–5643. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5636-5643.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandeu MM, Moussiliou A, Moiroux N, Padonou GG, Massougbodji A, Corbel V, Ndam NT. Optimized Pan-species and speciation duplex real-time PCR assays for Plasmodium parasites detection in malaria vectors. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokoples SE, Ndao M, Kowalewska-Grochowska K, Yanow SK. Multiplexed real-time PCR assay for discrimination of Plasmodium species with improved sensitivity for mixed infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:975–980. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01858-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walliker D, Quakyi IA, Wellems TE, McCutchan TF, Szarfman A, London WT, Corcoran LM, Burkot TR, Carter R. Genetic analysis of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1987;236:1661–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.3299700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]