Abstract

A 39-year-old female experienced dyspnea on exertion for eight months. Chest CT demonstrated findings of Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), including diffuse thin-walled cystic lesions. A surgical lung biopsy revealed human melanoma black-45-positive cell infiltration and aggregation, resulting in a diagnosis of sporadic LAM without tuberous sclerosis complex. Pelvic MRI showed two large tumors, one of which was in the myometrium and the other was in the retroperitoneal space. Because we were not able to exclude the presence of malignant tumors using MR imaging, the tumors were surgically resected. The histopathology demonstrated the resected tumors to be composed of LAM cells. The patient's symptoms worsened, and sirolimus was administered, which improved the dyspnea and pulmonary function. The adverse effect was mild liver damage. Following the initiation of treatment with sirolimus, transient elevation of the serum KL-6 level was detected without interstitial pneumonia. This LAM case complicated with large uterine and retroperitoneal tumors was successfully treated with surgical resection and sirolimus.

Keywords: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Uterine tumor, Retroperitoneal tumor, Sirolimus, KL-6

1. Introduction

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare, multiorgan disorder characterized by the proliferation of smooth muscle-like cells (LAM cells) primarily in the lungs and axial lymph nodes [1–6] Sporadic LAM is known to exclusively affect young females of reproductive age, with clinical manifestations such as progressive dyspnea on exertion, recurrent pneumothorax, hemoptysis, chylous pleural effusion and ascites [1,2]. Extrapulmonary involvement, including that of the kidneys and pelvic organs, is a common finding in patients with LAM; however, large uterine tumors are extremely rare. Although there is no conventional treatment, recent progress in research regarding the molecular pathogenesis of LAM has identified TSC gene abnormalities [7,8], indicating the participation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in the proliferation of LAM cells [9] and the potential for therapeutic approaches using mTOR inhibition. We experienced a case of sporadic LAM complicated with large uterine and retroperitoneal tumors that were treated with a surgical resection.

2. Case presentation

A 39-year-old Japanese female presented with a complaint of dyspnea on exertion that began eight months previously. Due to worsening of her symptoms, she consulted a general physician five months prior to visiting our department and was diagnosed with bronchial asthma. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) were initially introduced, without any apparent improvements in symptoms. The patient had no past medical history or smoking habits. A physical examination demonstrated no abnormal findings. In the laboratory findings obtained at the first visit, hypergammaglobulinemia and a mildly increased KL-6 level were observed. A blood gas analysis demonstrated hypoxemia (Table 1), and a pulmonary function test showed a moderate obstructive abnormality (FEV1%: 56.6%, %FEV1: 82.2%) with a reduced diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (%DLCO: 41.2%).

Table 1.

Laboratory data.

| CBC | Biochemistry | Immunochemistry | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 5300/μl | AST | 17 IU/l | CEA | 1.4 ng/ml |

| Neu. | 57.9% | ALT | 8 IU/l | SCC | 1.2 ng/ml |

| Ly. | 34.1% | LDH | 186 IU/l | CA125 | 38 U/ml |

| Mo. | 5.4% | ChE | 265 IU/l | CA19-9 | <1 U/ml |

| Eo. | 1.9% | T.Bil | 0.5 mg/dl | CA15-3 | 24 U/ml |

| Ba. | 0.7% | ALP | 160 IU/l | CA72-4 | 3 U/ml |

| RBC | 5.14 × 106/μl | γ-GTP | 14 IU/l | NSE | 11.3 ng/ml |

| Hb | 13.9 g/dl | TP | 8.2 g/dl | AFP | 8 ng/ml |

| Ht | 42.2% | Alb | 4.4 g/dl | KL-6 | 506 U/ml |

| Plt | 275 × 103/μl | BUN | 12 mg/dl | ||

| Cr | 0.78 mg/dl | Blood gas analysis(room air) | |||

| ESR1h | 24 mm | Na | 139 mmol/l | pH | 7.448 |

| PT | 100< % | K | 3.7 mmol/l | PaO2 | 75.2 Torr |

| APTT | 36.1 s | Cl | 107 mmol/l | PaCO2 | 28.1 Torr |

| Fbg | 321 mg/dl | Ca | 8.7 mg/dl | HCO3- | 19.2 mmol/l |

| CRP | <0.04 mg/dl | BE | −3.3 mmol/l | ||

| SaO2 | 96% | ||||

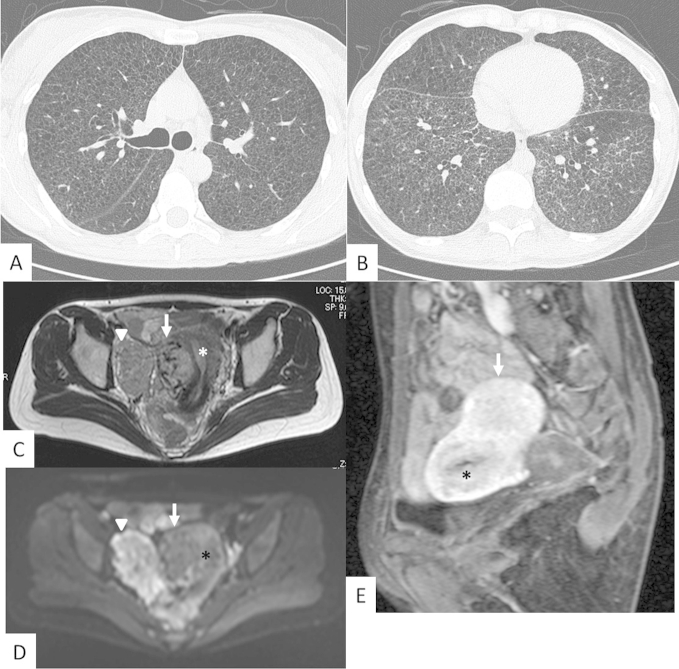

A chest X-ray image revealed bilateral reticular shadows and mild hyperinflation. Chest CT demonstrated diffusely distributed small cystic lesions, reticular opacity and micronodular lesions (Fig. 1A, B). These CT findings were suspicious to be LAM with lymphatic edema; hence, a histopathological evaluation was required to make a precise diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT and pelvic MRI. A and B. Chest CT demonstrates diffusely distributed small cystic lesions with reticular opacity. C and D. T2-weighted (C) and diffusion-weighted (D) MRI show two large tumors, one of which (arrow) is located in the myometrium and the other (arrowhead) is located adjacent to the pelvic wall. The diffusion-weighted MRI reveals that the two tumors have different patterns. The retroperitoneal tumor(arrowhead) is higher intensity than the uterine tumor. E. A sagittal section of pelvic MRI shows a tumor (arrow) in the myometrium of the uterus (asterisk) with a very strong contrasting effect.

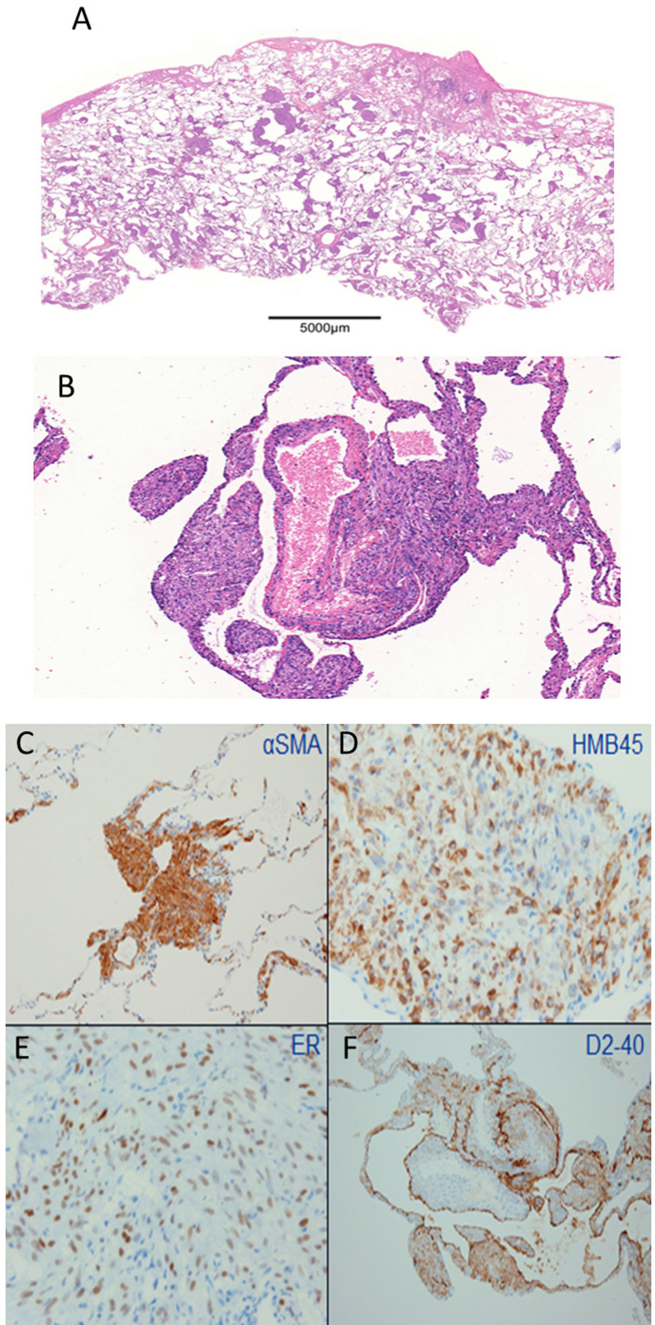

A lung biopsy specimen exhibited airspace dilatation with α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and human melanoma black (HMB)-45-positive smooth muscle-like cell (LAM cell) infiltration and aggregation. The immunohistochemical examination of the LAM cells was positive for both estrogen and progesterone receptors(ER, PR, respectively) (Fig. 2A–F). No multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (MMPH) lesions were observed in the specimen. Due to the absence of typical manifestations, which is consistent with the diagnostic criteria [10], and absence of family history of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), the patient was diagnosed with sporadic LAM.

Fig. 2.

Histopathological findings of the surgical biopsy of the lung. A and B. Hematoxylin-Eosin staining of the lung biopsy samples shows diffusely distributed small cystic lesions. Some cyst walls exhibit the accumulation of spindle-shaped cells. (B: ×100). C–F. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates positive staining for αSMA, HMB45, estrogen receptor (ER) and D2-40. (C and F: ×100, D and E: ×400).

Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound examinations showed a suspected leiomyoma of the uterus, but during systemic surveillance, pelvic MR imaging showed two large tumors with a very strong contrasting effect in the myometrium of the uterine corpus and retroperitoneal space (Fig. 1C–E). The CT of the abdomen shows paraaortic lymphnodes (not shown). There was a low possibility of leiomyoma due to the very strong contrasting effect in the early phase on MR imaging. Hence the proposed differential diagnoses were malignant tumor with hypervascularity and uterine LAM lesion. However, there was no report about large tumor to be composed of LAM cells in the myometrium. We discussed with gynecologists about non-surgical modality of treatments for these lesions, we were not able to exclude the presence of malignant tumors with rapid growing on MR imaging and thus the tumors were surgically resected. Total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) was performed due to bleeding and tumor adhesion to the pelvic wall.

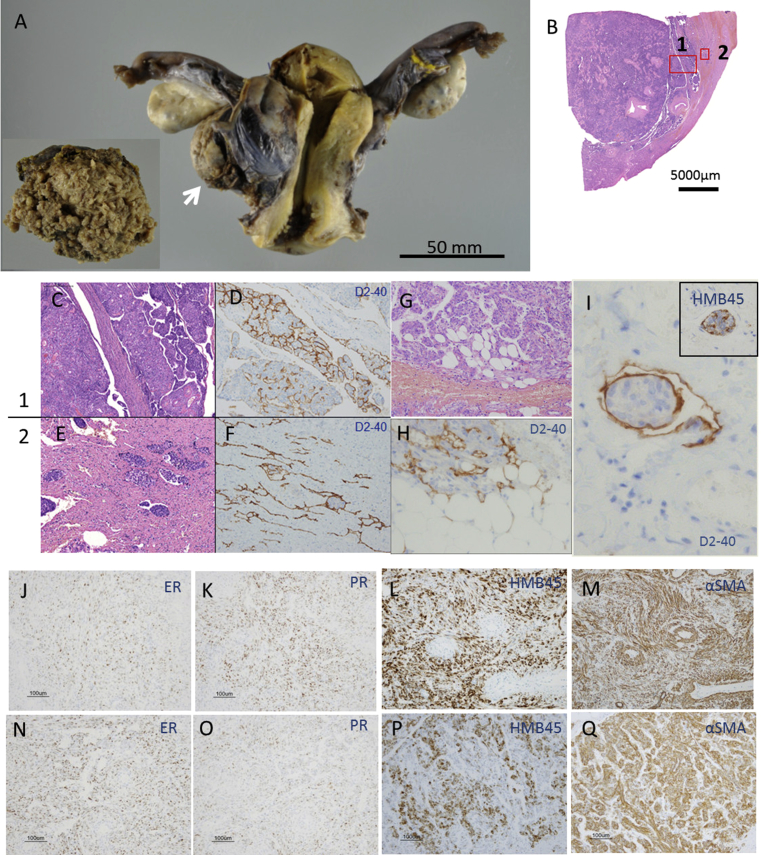

The size of tumor in the myometrium of the uterine corpus was 45 × 45 × 25 mm, while that of the retroperitoneal tumor was 70 × 60 × 35 mm (Fig. 3A). Macroscopically, well-circumscribed, yellowish and fragile tumors with cleft-like lesions were observed from the myometrium of the uterine corpus to the serous membrane borderline (Fig. 3B). The histopathological evaluation demonstrated the uterine and retroperitoneal tumors to be composed of αSMA and HMB-45-positive spindle-shaped cell aggregation accompanied by angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. These spindle-shaped cells were partially positive by ER and PR staining. The existence of lymphatic vessels was revealed by D2-40 staining. Accordingly, these tumors were diagnosed as uterine and retroperitoneal LAM lesions (Fig. 3C–Q). The histopathological findings of the retroperitoneal tumor correspond to the findings shown in uterine tumor.

Fig. 3.

Histopathological findings of the resected uterine and retroperitoneal tumors. A. A gross examination shows the uterine tumor resected via total hysterectomy with BSO. The tumor is in the right posterior wall of the uterus (arrow). The surface of the retroperitoneal tumor is rugged (inset). B. Low magnification view of the uterine tumor (H-E stain). C and D. High magnification view of the uterine tumor (H-E (C) and D2-40 (D) staining). (×100). E and F. High magnification view of the myometrium showing H-E (E) and D2-40 (F) staining. There are LAM cell clusters in the myometrium and slit-like lesions (D2-40-positive) which mean lymphatic vessels. (×100). G and H. High magnification view of the uterine tumor showing LAM cell infiltration in fat tissue (H-E (G: ×200) and D2-40 (H: ×400) staining). I. High magnification view of LAM cell cluster(LCC) enveloped by D2-40 positive lymphatic endothelial cells. LCC is composed by LAM cells with HMB-45 positive staining(inset). J, K, L and M. Low magnification view of the uterine tumor showing LAM cell infiltration (ER, PR, HMB45 and αSMA staining, ×100). N, O, P and Q. Low magnification view of the retroperitoneal tumor showing LAM cell infiltration (ER, PR, HMB-45 and αSMA staining, ×100).

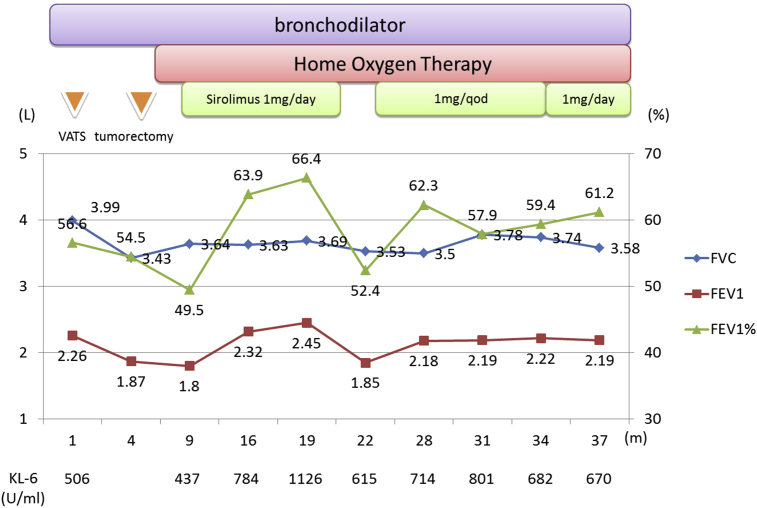

Simultaneous ICS/LABA and tiotropium inhalation was started for the treatment of dyspnea on exertion; however, no apparent improvements were observed. Severe oxygen desaturation was noted during a 6-min walking test, and home oxygen therapy was initiated. Total hysterectomy with BSO improved the slope of the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) from 130 ml per month to 14 ml per month, suggesting a pseudomenopause effect induced by BSO. In spite of the improvement in the patient's pulmonary function, progressive worsening of dyspnea with deterioration of activities of daily living was observed. Furthermore, the LAM histologic score (LHS), a prognostic predictor [11], was class 3, thus suggesting an unfavorable prognosis. Therefore, after obtaining informed consent, treatment with sirolimus (1 mg/day), an mTOR inhibitor, was initiated. After 10 months of sirolimus therapy, the FEV1 increased from 1.8 L to 2.45 L, with a marked improvement in the patient's respiratory symptoms. Because drug-induced liver damage occurred, the sirolimus treatment was interrupted for three months, resulting in a worsening of the FEV1 slope to with 200 ml per month. A reduced dose of sirolimus was administered following an improvement in the liver damage. As a consequence, the dyspnea and FEV1 slope recovered (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Clinical course Bronchodilators were initially introduced without any improvements in the patient's symptoms or pulmonary function. Uterine tumor resection concomitant with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) slightly reduced the decline in FEV1. However, home oxygen therapy was administered following tumorectomy, and treatment with sirolimus was initiated. An apparent improvement in the FEV1 was observed following the introduction of sirolimus treatment. No obvious regrowth of the uterine tumors has since been noted. The serum KL-6 level fluctuated during the sirolimus treatment.

Following the initiation of sirolimus treatment, mild elevation of the serum KL-6 level from 437 to 1126 (U/ml) was detected; however, serial high-resolution chest CT scans, which were performed every six month, demonstrated no apparent development of interstitial lung disease. Subsequently, the interruption and dose reduction of sirolimus spontaneously decreased the serum KL-6 level. There are no recurrence of the tumors and no enlargement of paraaortic lymphnodes.

3. Discussion

We experienced a case of sporadic LAM complicated with large uterine and retroperitoneal tumors. Treatment with BSO and subsequent sirolimus efficiently controlled the decline in the patient's pulmonary function and the regrowth of these tumors during the observation period. The recent identification of a tuberous sclerosis complex gene, TSC1/2, has improved understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of LAM [7,8]. TSC1/2 gene abnormalities induce LAM cell proliferation via the activation of mTOR; thus, mTOR inhibitors have been proposed to be effective treatment modalities. Indeed, the results of the recent multicenter international lymphangioleiomyomatosis efficacy and safety of sirolimus (MILES) phase III trial demonstrated that sirolimus therapy significantly stabilizes declines in the pulmonary function (FEV1 slope) and is associated with improvements in symptoms and the quality of life [5]. In the present case, although BSO may reduce the decline in the slope of FEV1, we observed a marked improvement in the patient's dyspnea and pulmonary function (FEV1) following the initiation of treatment with sirolimus. The efficacy of sirolimus was further confirmed by the worsening of symptoms and decline in the pulmonary function observed during the transient cessation of sirolimus therapy.

Adverse reactions during sirolimus treatment include liver dysfunction and interstitial pneumonia. We observed mild liver dysfunction that was improved by the transient cessation of sirolimus and subsequently efficiently prevented with dose reduction. Elevation of the serum KL-6 level, a marker of interstitial pneumonia, was also observed in association with the initial dose of sirolimus. Although we suspected sirolimus-induced interstitial pneumonia, the chest CT findings revealed improvements in reticular opacity and lymphatic edema, and no abnormal findings consistent with interstitial pneumonia were observed. The cause of the KL-6 elevation was unclear.

Due to the absence of clinical manifestations for TSC, the patient was diagnosed with sporadic LAM. A recent paper demonstrated that nine of 10 (90%) patients with sporadic LAM were complicated with uterine LAM based on microscopic examinations, while five of eight (63%) patients exhibited adnexal LAM cell infiltration [12]. However, the presence of large uterine LAM on a detailed histopathological examination has not been previously reported. The histopathological findings demonstrated that uterine and retroperitoneal lesions were composed of spindle-shaped cells corresponding to LAM cells. Furthermore, LAM cell clusters enveloped by D2-40 positive lymphatic endothelial cells were present in lymphatic vessels and LAM cells infiltrated into fat tissue with lymphangiogenesis (Fig. 3G, H and I). The slit like lesions composed of lymphatic vessels were also demonstrated and previous paper [12] reported that these findings are characteristic for sporadic LAM. Accordingly, the histopathological findings of large uterine and retroperitoneal tumors in the present case are consistent with a diagnosis of LAM lesions, which were complicated with sporadic LAM.

No conventional therapeutic strategies for treating pelvic LAM tumors have been demonstrated; however, the successful treatment using a combination of surgical resection and an mTOR inhibitor observed in this study offers a potentially effective treatment modality in cases of pulmonary LAM complicated with extrapulmonary large LAM lesions. In one trial, angiomyolipomas regrew following the discontinuation of sirolimus in 13 of 18 (72%) patients [13]. Therefore, we believe that the administration of maintenance therapy with sirolimus is necessary for disease control and that the safety and efficacy of sirolimus must be demonstrated for long-term use.

4. Summary

We experienced a rare case of sporadic LAM complicated with large uterine and retroperitoneal LAM lesions. Combination treatment consisting of surgical resection and subsequent mTOR inhibition improved the patient's respiratory symptoms without tumor regrowth.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Toshio Kumasaka, Department of Pathology, Japanese Red Cross Medical Center and Aikou Okamoto, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Jikei University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Carrington C.B., Cugell D.W., Gaensler E.A., Marks A., Redding R.A., Schaaf J.T. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: physiologic-pathologic-radiologic correlations. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1977;116:977–995. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.116.6.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrin B., Liebow A.A., Friedman P.J. Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis: a review. Am. J. Pathol. 1975;79:348–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein S.M., Newell J.D., Jr., Adamczyk D., Mortenson R.L., King T.E., Jr., Lynch D.A. How common are renal angiomyolipomas in patients with pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;152:2138–2143. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohman D.W., Noghrehkar D., Ratnayake S. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a review. Eur. J. Intern Med. 2008;19:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack F.X., Inoue Y., Moss J., Singer L.G., Strange C., Nakata K. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1595–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashida M., Seyama K., Inoue Y., Fujimoto K., Kubo K., Respiratory Failure Research Group of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare The epidemiology of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in Japan: A nationwide cross-sectional study of presenting features and prognostic factors. Respirology. 2007;12:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carsillo T., Astrinidis A., Henske E.P. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2000;97:6085–6090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato T., Seyama K., Fujii H., Maruyama H., Setoguchi Y., Iwakami S. Mutation analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in Japanese patients with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;47:20–28. doi: 10.1007/s10038-002-8651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Q., Guan K.-L. Expanding mTOR signaling. Cell. Res. 2007;17:666–681. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Northrup H., Krueger D.A., International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Diagnostic Criteria Update: Recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013;49:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui K., Beasley M.B., Nelson W.K., Barnes P.M., Bechtle J., Falk R. Prognostic significance of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis histologic score. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001;25:479–484. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi T., Kumasaka T., Mitani K., Terao Y., Watanabe M., Oide T. Prevalence of uterine and adnexal involvement in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 10 patients. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011;35:1776–1785. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318235edbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bissler J.J., McCormack F.X., Young L.R., Elwing J.M., Chuck G., Leonard J.M. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:140–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]