Abstract

Objective

To examine the patterns of care, predictors, and impact of chemotherapy on survival in elderly women diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma.

Methods

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database was used to identify women 65 years or older diagnosed with stage I-II uterine carcinosarcoma from 1991 through 2007. Multivariable logistic regression and Cox-proportional hazards models were used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 462 women met the eligibility criteria; 374 had stage I, and 88 had stage II uterine carcinosarcoma. There were no appreciable differences over time in the percentages of women administered chemotherapy for early stage uterine carcinosarcoma (14.7% in 1991–1995, 14.9% in 1996–2000, and 17.9% in 2001–2007, P=0.67). On multivariable analysis, the factors positively associated with receipt of chemotherapy were younger age at diagnosis, higher disease stage, residence in the eastern part of the United States, and lack of administration of external beam radiation (P<0.05). In the adjusted Cox-proportional hazards regression models, administration of three or more cycles of chemotherapy did not reduce the risk of death in stage I patients (HR: 1.45, 95% CI: 0.83–2.39) but was associated with non-significant decreased mortality in stage II patients (HR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.32–1.95).

Conclusions

Approximately 15–18% of elderly patients diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma were treated with chemotherapy. This trend remained stable over time, and chemotherapy was not associated with any significant survival benefit in this patient population.

Keywords: carcinosarcoma, outcomes, patterns of care, chemotherapy

Introduction

Uterine carcinosarcoma is a rare gynecologic malignancy, with incidence of fewer than three per 100,000 women per year [1]. Although carcinosarcoma used to be considered a type of uterine sarcoma, this malignancy has recently been reclassified as a dedifferentiated or metaplastic form of endometrial carcinoma [2]. However, carcinosarcomas behave more aggressively than the most undifferentiated of the ordinary type of endometrial carcinoma [3]. Compared to endometrial adenocarcinoma, carcinosarcomas are more likely to present with advanced stage disease at the time of diagnosis [4]. Furthermore, recurrence rates for carcinosarcoma are approximately 50%, and survival is poor even when the tumor is limited to the uterine corpus [5].

Because most patients’ recurrences are distant, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend adjuvant chemotherapy as a treatment option in patients diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma [6]. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 150 study showed that chemotherapy was associated with better survival than whole abdominal irradiation, but this difference was not statistically significant, and the study included all stages of uterine carcinosarcoma [7]. Moreover, given that women over the age of 65 account for nearly 50% of diagnosed uterine carcinosarcoma in the United States [5] and that often such patients have medical co-morbidities and poor performance status, many patients may be at high risk for chemotherapy-related toxicity [5]. Thus, the objectives of this study were to determine the frequency of use of chemotherapy for treatment of elderly women diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma, assess changes in treatment over time, and determine the predictors and outcomes of chemotherapy. To accomplish these goals, we used a large cohort derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database of the National Cancer Institute.

Methods

Study cohort

SEER is a population-based cancer registry that collects information on all incident cancers. The Medicare database includes data on patients with Medicare part A (inpatient) and part B (outpatient), including billed claims and services [8]. Eligible patients for this study were those diagnosed at the age of 65 years and older with primary uterine carcinosarcoma between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2007. Only patients diagnosed with stage I or stage II uterine carcinosarcoma who underwent a cancer-directed surgery (hysterectomy) were included in the analysis. We excluded patients who were members of a Health Maintenance Organization at any point in the 12-month period before and after their cancer diagnosis, those enrolled in Medicare because of end-stage renal disease and dialysis, and patients with other primary tumors. This study was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Boards of Washington University School of Medicine and Wayne State University School of Medicine.

Data extraction

Age at diagnosis was classified into five-year intervals. Stage was assigned from the recorded extent-of-disease codes according to the revised 2009 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging criteria for endometrial cancer. Surgical procedure data were derived from site-specific surgery codes. Data concerning the performance of lymph node dissection and lymph node metastasis were derived from pathology codes. Information on use of adjuvant external beam radiation therapy and vaginal brachytherapy was collected. Medicare claims files (physician [NCH], outpatient [OUTPAT], and hospital [MEDPAR]) were used to identify receipt of chemotherapy within six months of cancer diagnosis. Receipt of fewer than three months and three or more months of chemotherapy was separately recorded for purposes of stratification. We used the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes to identify patients who had received a specified chemotherapeutic drug within 180 days after their cancer diagnosis. For patients who did not have specific chemotherapy HCPCS codes, we used HCPCS codes (J8510, J9999, 964XX, 965XX, Q0083-85, Q0163-Q0185, G0355-G0363), ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes (V581, V662, V672), procedure or surgery codes (9925), and codes from the 2005 Medicare oncology demonstration project to capture any evidence that an unspecified chemotherapeutic drug was administered. Socioeconomic status of each patient was evaluated by describing the education and income level of the census tract in which the patient resided at the time of diagnosis. We included a modified version of the Charlson comorbidity index, which was based on the ICD-9 diagnostic and procedure codes as well as on the HCPS codes for ten conditions, captured in the 12-month period before cancer diagnosis [9, 10]. Area of residence was categorized as urban or rural, and the registry in which each patient was recorded was noted. Each patient’s vital status (alive vs. dead) was recorded. Because of Medicare confidentiality rules, we could not show data in which cells contained fewer than 11 patients (denoted by * in Table 1). In cases where a number less than 11 could be deduced by providing a related number, data were suppressed (denoted by ** in Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the cohort

| All patients (n=462) | Stage I (n=374) | Stage II (n=88) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) |

| 65–69 | 114 | 24.7 | 97 | 25.9 | 17 | 19.3 |

| 70–74 | 117 | 25.3 | 91 | 24.3 | 26 | 29.6 |

| 75–79 | 113 | 24.5 | 86 | 23.0 | 27 | 30.7 |

| ≥80 | 118 | 25.5 | 100 | 26.8 | 18 | 20.4 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 384 | 83.2 | 318 | 85.0 | 66 | 75.0 |

| Black | 57 | 12.3 | 37 | 9.9 | ¶22 | 25.0 |

| Other | 21 | 4.5 | 19 | 5.1 | ||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1991–1995 | 116 | 25.2 | 92 | 24.6 | 24 | 27.3 |

| 1996–2000 | 94 | 20.3 | 75 | 20.1 | 19 | 21.6 |

| 2001–2007 | 252 | 54.5 | 207 | 55.3 | 45 | 51.1 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 190 | 41.2 | 150 | 40.1 | 40 | 45.5 |

| Unmarried | 252 | 54.5 | 205 | 54.8 | ¶48 | 54.5 |

| Unknown | 20 | 4.3 | 19 | 5.1 | ||

| Area of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 417 | 90.3 | 338 | 90.4 | ** | - |

| Rural | 45 | 9.7 | 36 | 9.6 | * | - |

| SEER registry | ||||||

| Northeast | 90 | 19.5 | 72 | 19.3 | 18 | 20.5 |

| Midwest | 116 | 25.1 | 97 | 25.9 | 19 | 21.6 |

| West | 191 | 41.3 | 157 | 42.0 | 34 | 38.6 |

| South | 65 | 14.1 | 48 | 12.8 | 17 | 19.3 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Lowest (first) quartile | 116 | 25.1 | 86 | 23.0 | 30 | 34.1 |

| Second quartile | 112 | 24.2 | 95 | 25.4 | 17 | 19.3 |

| Third quartile | 112 | 24.2 | 91 | 24.3 | 21 | 23.9 |

| Highest (fourth) quartile | 122 | 26.5 | 102 | 27.3 | 20 | 22.7 |

| Education | ||||||

| Lowest (first) quartile | 114 | 24.7 | 97 | 25.9 | 17 | 19.3 |

| Second quartile | 121 | 26.2 | 98 | 26.2 | 23 | 26.1 |

| Third quartile | 109 | 23.6 | 85 | 22.7 | 24 | 27.3 |

| Highest (fourth) quartile | 118 | 25.5 | 94 | 25.2 | 24 | 27.3 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||

| 0 | 320 | 69.3 | 259 | 69.3 | 61 | 69.3 |

| ≥1 | 142 | 30.7 | 115 | 30.7 | 27 | 30.7 |

| Stage | ||||||

| IA | 259 | 56.1 | 259 | 69.3 | -- | -- |

| IB | ¶115 | 24.9 | ¶115 | 30.7 | -- | -- |

| I NOS | -- | -- | ||||

| II | 88 | 19.0 | -- | 88 | 100 | |

| Lymphadenectomy | ||||||

| Yes | 307 | 66.5 | 257 | 68.7 | 50 | 56.8 |

| No | 155 | 33.5 | 117 | 31.3 | 38 | 43.2 |

| Adjuvant external beam radiation | ||||||

| No | 274 | 59.3 | 236 | 63.1 | 38 | 43.2 |

| Yes | 188 | 40.7 | 138 | 36.9 | 50 | 56.8 |

| Adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy | ||||||

| No | 376 | 81.4 | 313 | 83.7 | 63 | 71.6 |

| Yes | 86 | 18.6 | 61 | 16.3 | 25 | 28.4 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 386 | 83.5 | 316 | 84.5 | ¶73 | 83.0 |

| <3 months | 20 | 4.3 | 17 | 4.5 | ||

| ≥3 months | 56 | 12.2 | 41 | 11.0 | 15 | 17.0 |

Cell size < 11 (SEER-Medicare confidentiality rule)

Cell size suppressed to comply with SEER-Medicare confidentiality rule

Cells merged to comply with SEER-Medicare confidentiality rule

Statistical analyses

The distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics between patients diagnosed with stage I and stage II uterine carcinosarcoma were compared by using Chi-square tests. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed to examine the predictors of chemotherapy, external beam radiation, and vaginal brachytherapy. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compute survival probability data, and the log-rank test was used to compare differences between groups. Cox proportional hazards regression models were developed to examine overall survival while controlling for other clinical and demographic characteristics. SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all statistical analyses. All P-values reported are two-tailed, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients

A total of 462 women met the eligibility criteria. Of these, 374 had stage I, and 88 had stage II uterine carcinosarcoma (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 76 years (range: 66 years–93 years). The majority of the patients were white and resided in urban areas. The geographic distributions of the patients were as follows: 19% from the northeast, 25% from the midwest, 41% from the west, and 14% from the south. A large portion (31%) of the patients had co-morbidities as determined by a modified Charlson co-morbidity index score equal to or greater than one. Lymphadenectomy was performed in 66% of the patients. Adjuvant external beam radiation was administered in 41% of the patients. Only 16% of the patients received adjuvant chemotherapy; 40 of these 76 patients received a platinum agent either alone or in combination with other cytotoxic agents. Most patients who received platinum agents were treated with a doublet (n=29), the most common of which was platinum in combination with taxanes such as paclitaxel or docetaxel. The type of chemotherapy administered in the remaining 36 patients was either unspecified or included a non-platinum based regimen.

Clinical and demographic characteristics were compared between stage I and stage II patients (Table 1). More patients with stage II than with stage I uterine carcinosarcoma underwent a lymphadenectomy or received adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy, vaginal brachytherapy, or external beam radiation. Overall, the use of chemotherapy for patients with early stage uterine carcinosarcoma did not change significantly over time (14.7% in 1991–1995; 14.9% in 1996–2000; and 17.9% in 2001–2007; P=0.67). Similarly, the rates of administration of external beam radiation did not differ over time for these patients (40.5% in 1991–1995; 37.2% in 1996–2000; and 42.1% in 2001–2007; P=0.72). In contrast, the use of vaginal brachytherapy increased over time (11.2% in 1991–1995; 19.2% in 1996–2000; and 21.8% in 2001–2007; P=0.05), but this change was not statistically significant.

Predictors of use of adjuvant therapy

We used multivariable logistic regression to analyze the predictors of receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 2). Age, location of SEER registry, stage, and receipt of adjuvant external beam radiation emerged as significant independent predictors. Women ≥75 years of age were less likely to be treated with chemotherapy, as were those who received external beam radiation for treatment of their uterine carcinosarcoma. Patients residing in the western or southern parts of the United States were also less likely to be treated with chemotherapy than those residing in the northeastern part. Patients diagnosed with uterine carcinosarcoma of stage IB or higher were more likely to be treated with chemotherapy than those diagnosed with stage IA disease. In analysis of predictors of treatment with external beam radiation, only higher stage, lack of administration of three or more cycles of chemotherapy, and receipt of adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy showed significant positive associations (Table 2). The positive predictors for receipt of vaginal brachytherapy included later year of diagnosis (after 2001), lack of significant co-morbidities, receipt of external beam radiation, and treatment with three or more cycles of chemotherapy (Table 2). Patients residing in the western part of the United States were less likely to be treated with vaginal brachytherapy than those living in the northeastern part of the country.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression models of predictors of receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, external beam radiation, and vaginal brachytherapy

| Chemotherapy | External beam radiation | Vaginal brachytherapy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| 65–69 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 70–74 | 0.67 (0.34–1.33) | 1.06 (0.58–1.92) | 0.77 (0.37–1.61) |

| 75–79 | *0.30 (0.14–0.68) | 0.71 (0.38–1.31) | 0.62 (0.29–1.36) |

| ≥80 | *0.28 (0.12–0.64) | 0.47 (0.25–0.90) | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) |

| Race | |||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 0.98 (0.38–2.53) | 0.57 (0.26–1.26) | 0.62 (0.21–1.81) |

| Other | 1.68 (0.48–5.89) | 1.39 (0.48–2.51) | 1.18 (0.31–4.51) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 1991–1995 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1996–2000 | 0.73 (0.30–1.77) | 0.72 (0.37–1.40) | 2.33 (0.95–5.72) |

| 2001–2007 | 1.17 (0.56–2.43) | 0.95 (0.54–1.67) | *2.54 (1.15–5.59) |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Married | 1.03 (0.58–1.83) | 0.81 (0.52–1.27) | 1.22 (0.68–2.18) |

| Unknown | 0.26 (0.03–2.14) | 0.41 (0.12–1.38) | 0.40 (0.05–3.48) |

| Area of residence | |||

| Urban | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Rural | 0.41 (0.11–1.60) | 1.10 (0.48–2.51) | 1.36 (0.49–3.80) |

| SEER registry | |||

| Northeast | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Midwest | 0.55 (0.26–1.19) | 1.20 (0.61–2.39) | 0.48 (0.20–1.15) |

| West | *0.28 (0.12–0.63) | 1.19 (0.60–2.35) | *0.38 (0.16–0.86) |

| South | *0.23 (0.08–0.66) | 0.75 (0.33–1.72) | 0.62 (0.23–1.69) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Lowest (first) quartile | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Second quartile | 0.81 (0.35–1.91) | 0.94 (0.50–1.79) | 1.31 (0.56–3.06) |

| Third quartile | 0.93 (0.40–2.20) | 0.88 (0.44–1.73) | 0.81 (0.32–2.03) |

| Highest (fourth) quartile | 0.52 (0.20–1.35) | 0.98 (0.46–2.06) | 0.87 (0.33–2.28) |

| Education | |||

| Lowest (first) quintile | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Second quintile | 0.76 (0.34–1.68) | 1.07 (0.56–2.05) | 0.80 (0.35–1.86) |

| Third quintile | 0.43 (0.17–1.09) | 1.60 (0.79–3.24) | 0.59 (0.23–1.49) |

| Highest (fourth) quartile | 0.65 (0.24–1.76) | 1.24 (0.55–2.82) | 0.60 (0.21–1.69) |

| Comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 0.58 (0.30–1.11) | 0.95 (0.60–1.51) | *0.37 (0.18–0.74) |

| Stage | |||

| IA | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| IB | *2.15 (1.10–4.20) | *2.14 (1.27–3.61) | 1.50 (0.75–3.01) |

| I NOS | 0.66 (0.07–6.05) | 0.19 (0.02–1.89) | 2.05 (0.22–19.20) |

| II | *2.26 (1.08–4.73) | *3.00 (1.69–5.35) | 2.06 (1.00–4.23) |

| Lymphadenectomy | |||

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 1.64 (0.87–3.12) | 1.21 (0.74–1.96) | 1.43 (0.75–2.71) |

| Adjuvant external beam radiation | |||

| No | Referent | -- | Referent |

| Yes | *0.39 (0.21–0.74) | -- | *7.38 (3.89–14.00) |

| Adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy | |||

| No | Referent | Referent | -- |

| Yes | 1.62 (0.80–3.25) | *6.62 (3.58–12.24) | -- |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| No | -- | Referent | Referent |

| <3 months | -- | 1.12 (0.41–3.05) | 0.13 (0.01–1.08) |

| ≥3 months | -- | *0.21 (0.10–0.47) | *3.28 (1.52–7.07) |

P<0.05

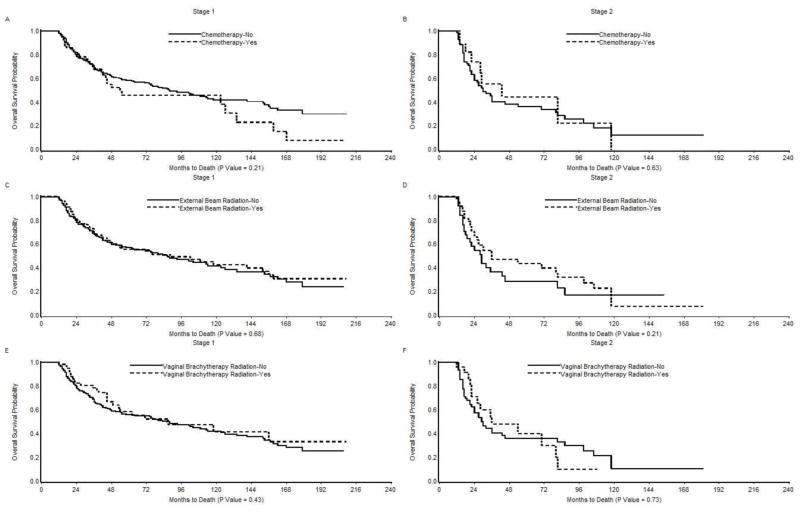

Association of therapies with survival

We performed a Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis to evaluate the impact of adjuvant therapy on overall survival in women with stage I/II uterine carcinosarcoma (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in median survival between stage I patients treated with and without chemotherapy (54 months vs. 88 months, P= 0.21), external beam radiation (88 months vs. 86 months, P=0.68), or vaginal brachytherapy (87 months vs. 86 months, P= 0.43). When analysis was limited to stage II patients, the median survival was higher for patients treated with adjuvant treatments than for those who did not receive these treatments (chemotherapy: 43 months vs. 30 months; external beam radiation: 36 months vs. 29 months; vaginal brachytherapy: 36 months vs. 29 months); however, these differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Overall Survival in (A) Stage I patients treated with and without chemotherapy; (B) Stage II patients treated with and without chemotherapy; (C) Stage I patients treated with and without external beam radiation; (D) Stage II patients treated with and without external beam radiation; (E) Stage I patients treated with and without vaginal brachytherapy; and (F) Stage II patients treated with and without vaginal brachytherapy.

Cox proportional hazards models were developed to examine the influence of adjuvant therapy on survival while accounting for other prognostic variables (Table 3). Adjuvant treatment with three or more cycles of chemotherapy, external beam radiation, or vaginal brachytherapy did not affect survival in patients with stage I uterine carcinosarcoma. Although there was a trend towards improved survival with administration of adjuvant external beam radiation and with receipt of three or more cycles of chemotherapy in stage II patients, these effects were not statistically significant. Variables significantly associated with increased risk of death among stage I patients included advanced patient age, black race, co-morbidities, stage IB disease, and receipt of treatment in an earlier time period (before 2001). Among stage II patients, performance of lymphadenectomy was associated with significantly improved survival. Additionally, stage II patients who resided in the northeastern part of the United States had significantly higher survival rates than those residing in the western part of the country.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards models of overall survival in women with stage I-II uterine carcinosarcoma

| Stage I | Stage II | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) |

| 65–69 | Referent | Referent |

| 70–74 | *1.81 (1.13–2.93) | 0.81 (0.25–2.84) |

| 75–79 | 1.51 (0.90–2.54) | 0.75 (0.24–2.49) |

| ≥80 | *2.96 (1.88–4.75) | 0.72 (0.19–2.76) |

| Race | ||

| White | Referent | Referent |

| Black | *2.43 (1.40–4.08) | 1.87 (0.67–5.15) |

| Other | 0.54 (0.19–1.26) | 2.43 (0.25–18.03) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 1991–1995 | Referent | Referent |

| 1996–2000 | 0.93 (0.60––1.43) | 1.18 (0.50–2.76) |

| 2001–2007 | *0.57 (0.37–0.88) | 0.87 (0.37–2.09) |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | Referent | Referent |

| Married | 1.19 (0.86–1.64) | 0.75 (0.33–1.78) |

| Unknown | 0.77 (0.29–1.69) | *26.24 (1.05–296.45) |

| Area of residence | ||

| Urban | Referent | Referent |

| Rural | 1.11 (0.60–2.01) | 1.37 (0.42–4.13) |

| SEER registry | ||

| Northeast | Referent | Referent |

| Midwest | 1.49 (0.90–2.49) | *4.61 (1.38–16.88) |

| West | 1.58 (0.97–2.64) | 2.20 (0.80–6.56) |

| South | 1.22 (0.65–2.25) | 2.00 (0.61–6.64) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Lowest (first) quartile | Referent | Referent |

| Second quartile | 0.79 (0.50–1.25) | 0.43 (0.15–1.15) |

| Third quartile | 1.05 (0.65–1.71) | 1.94 (0.69–5.59) |

| Highest (fourth) quartile | 1.19 (0.67–2.13) | 0.57 (0.15–2.04) |

| Education | ||

| Lowest (first) quartile | Referent | Referent |

| Second quartile | 1.05 (0.65–1.71) | 0.55 (0.15–2.11) |

| Third quartile | 1.25 (0.75–2.11) | 0.54 (0.15–2.03) |

| Highest (fourth) quartile | 1.43 (0.79–2.61) | 0.63 (0.13–3.13) |

| Comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | *1.57 (1.09–2.25) | 1.44 (0.68–3.03) |

| Stage | ||

| IA | Referent | -- |

| IB | *1.72 (1.20–2.45) | -- |

| I NOS | *0.20 (0.01–0.90) | -- |

| II | -- | -- |

| Lymphadenectomy | ||

| No | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 0.94 (0.67–1.33) | *0.36 (0.18–0.71) |

| Adjuvant external beam radiation | ||

| No | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 0.99 (0.69–1.40) | 0.65 (0.32–1.29) |

| Adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy | ||

| No | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 0.99 (0.60–1.62) | 1.37 (0.62–2.90) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| No | Referent | Referent |

| <3 months | 1.19 (0.59–2.22) | *** |

| ≥3 months | 1.45 (0.83–2.39) | 0.83 (0.32–1.95) |

P<0.05

Numbers too small to make any reliable estimates

Discussion

Cancer treatment in the elderly poses a unique challenge because many of these patients have pre-existing medical co-morbidities [11]. Additionally, there is a natural decline of organ function, including reduced bone marrow reserve, which may significantly limit these patients’ ability to tolerate aggressive cancer treatments [12]. Several reports have shown that elderly patients do not derive the same benefit from cancer treatments as the general population in clinical trials. For example, irinotecan therapy in metastatic colon cancer [13] and the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer [14] have both proved disappointing in the elderly Medicare population. Discrepant results may be because treatment was not used as recommended in the clinical trials because elderly patients may not tolerate aggressive therapies like their younger counterparts; such an effect was shown in studies of patients with ovarian cancer [15, 16]. As a result, some investigators have recommended designing trials to assess the effectiveness of different treatments specifically in elderly patients [17].

We conducted a population-based analysis using the SEER-Medicare database of the National Cancer Institute to determine the use and effectiveness of chemotherapy in elderly patients diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma. We found that only 15–18% of elderly women with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma received treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy, despite the NCCN guidelines supporting its use in the treatment of these patients. We could not determine whether the underuse of chemotherapy in this patient population was due to lack of offer by the physicians or lack of acceptance by the patients. Indeed, studies of cancers of other sites have shown that elderly patients are less likely to be offered treatments even when the treatments are thought to be curative [18–20]. Patient preferences may also contribute to treatment decisions. For example, elderly patients are more likely to have medical co-morbidities [11] and diminished functional ability [21] and social resources [22], which may negatively influence their willingness to accept additional treatments.

Interestingly, significant regional variation was found with regards to administration of chemotherapy for patients with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma, and these variations persisted after adjusting for various demographic and socio-economic variables. This finding suggests that location affects the treatment administered to elderly women diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma in the US. We could not determine whether this regional variation is a reflection of lack of availability of suitable facilities and trained providers in certain regions or reluctance of physicians/patients in these areas to administer/undergo aggressive treatment. However, similar observations have been made with cancers of other body sites [23, 24].

The low rate of use of adjuvant chemotherapy did not shift over the duration of the study period, which is not unexpected given that none of the trials conducted during this time period to evaluate the usefulness of adjuvant chemotherapy in treatment of early stage uterine carcinosarcoma showed a statistically significant survival benefit [25]. Given the trend towards improved survival with chemotherapy in the GOG 150 trial [7] and increased use of chemotherapy for all advanced stage endometrial cancers in general [26], one might expect use of adjuvant chemotherapy for carcinosarcomas to have increased since 2007 (year GOG 150 was published). However, because our cohort only included patients diagnosed up to and including 2007, we could not be assess this possibility.

Most patients in our study were treated with a platinum/taxane combination despite the fact that, at the time they were treated, there was no level-one evidence to support the efficacy of this combination in treatment of uterine carcinosarcoma. Ifosfamide has been shown to be the most active single agent in the treatment of uterine carcinosarcoma (response rate 18–36%) [27]. Furthermore, several GOG studies have shown the superiority of ifosfamide-based combinations over ifosfamide alone in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma [28, 29]. Excellent response rates have recently been reported for combination chemotherapy of carboplatin plus paclitaxel in patients with advanced or recurrent uterine carcinosarcoma [30]. The encouraging results of this study have led the GOG to initiate a phase III randomized trial (GOG 261) to compare the effectiveness of the carboplatin/taxol combination to that of the current standard ifosfamide/taxol combination in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma. This trial is currently accruing and will provide further evidence regarding the effectiveness of carboplatin/taxol combination in the treatment of uterine carcinosarcoma.

Our finding that adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with a significant improvement in overall survival in patients with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma is consistent with findings from several other studies. For example, Cantrell et al. performed a large multi-institutional study to evaluate the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage I–II uterine carcinosarcoma [31]. Chemotherapy was associated with an improved rate of progression-free survival, but overall survival was not significantly influenced by this treatment [31]. Likewise, the GOG 20 study, which compared postoperative doxorubicin versus no further therapy in patients with stage I–II uterine sarcoma, including uterine carcinosarcoma, reported no observed benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy with regards to either progression-free or overall survival [25]. More recently, the GOG 150 study compared whole abdominal irradiation (WAI) to chemotherapy with cisplatin, ifosfamide, and mesna for post-operative treatment in patients with stage I–IV uterine carcinosarcomas [7]. Although a favorable trend was noted, there was no statistically significant advantage in recurrence rate (relative hazard= 0.79, 95% CI: 0.53–1.18) or survival for adjuvant chemotherapy (relative hazard: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.48–1.05) over WAI in these patients.

In our study, many patients were treated with radiation. Although there was a trend towards improved survival with radiation in stage II patients, this treatment did not confer any significant survival benefit in either stage I or stage II uterine carcinosarcoma. The usefulness of adjuvant pelvic radiation in patients with early stage uterine sarcomas was evaluated in a randomized controlled trial conducted by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [32]. Adjuvant pelvic radiation was associated with a significantly reduced risk of pelvic recurrence in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma (n = 91), but had no significant impact on either progression-free or overall survival in these patients [32].

Given that neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy appear to significantly affect survival in this patient population, why are we still recommending it? We do so because patients with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma are at significant risk of developing abdominal/distant recurrences, suggesting a need for systemic therapy in these patients [5]. Unfortunately, we could not assess the impact of chemotherapy on recurrence patterns in this study, as site of first recurrence data were not available. However, an analysis of the patterns of failure on GOG 150 revealed that patients who received chemotherapy had a lower rate of abdominal relapse and a higher rate of vaginal relapse than those who received WAI [8]. These results raise the question of whether patients should receive radiation therapy in addition to chemotherapy. However, in the GOG 150 trial, those who received WAI had a significantly higher rate of serious late adverse events than those who did not [7]; this result argues against the routine use of postoperative pelvic radiation to achieve local control. By contrast, vaginal brachytherapy may have markedly less risk of late effects and may be beneficial in combination with chemotherapy [33]. A few retrospective studies have examined the use of multimodality treatment–including a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation – and have shown encouraging results in these patients [34, 35].

We observed two notable correlations with survival outcomes. First, black women were more likely than white women to die from their disease. This finding is consistent with the results reported by others and is likely due to multiple factors and not just disparate access to health care facilities and treatment choices [7, 36]. Additionally, lymphadenectomy was an independent predictor of survival in stage II patients. This could be due to the lack of identification and therefore retention of occult stage IIIC patients among those stage II patients who did not undergo lymphadenectomy. Alternatively, patients who underwent lymphadenectomy may have had less co-morbid illness, better performance status, or were operated on by a gynecologic oncologist, all of which can confound survival data [36].

The major strength of our study is the examination of a large number (n = 462) of patients with this relatively rare tumor. Because of our large sample size, we were able to robustly analyze the impact of chemotherapy on survival in stage I and stage II uterine carcinosarcomas. All previous studies have combined these two stage-categories because of a small sample size. Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, we lacked data on performance status and patient preferences. Second, given that lymph node dissection was not performed in all patients, understaging was possible. There is some suggestion that patients with incomplete surgical staging are more likely to be offered chemotherapy [37]. This could result in an over-representation of understaged patients in the chemotherapy group and a false underestimate of the chemotherapy-related survival benefit. Third, we included only patients at least 65 years of age, so our results may not be generalizable to younger patients. However, in the United States, women over the age of 65 account for nearly 50% of diagnosed uterine carcinosarcoma [5].

Fourth, although a large number of patients from the SEER-Medicare database were included, our study may not have been adequately powered to detect small differences in survival related to the administration of adjuvant treatments in patients with stage II disease. Fifth, our study did not include patients diagnosed after 2007. More recently diagnosed patients were excluded to ensure sufficient follow-up to assess the association of treatment with survival. Sixth, although the use of chemotherapy was recorded, details regarding the chemotherapy cycles and dosing were not available. Seventh, the SEER database’s lack of important information regarding disease recurrence precluded an analysis of patterns of failure in these patients. Finally, decisions about treatment of the patients in our cohort were based on many uncontrolled and unknown factors, which may have influenced the observed treatment-related outcomes.

In summary, in this population-based data set, very few elderly patients with early stage uterine carcinosarcoma were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Patterns of treatment did not change over the duration of the study period, and chemotherapy was not associated with improved overall survival. Although not as definitive as those from a randomized controlled trial, our findings provide useful information about the community-level outcomes that can be expected from the usage of chemotherapy for treatment of elderly women diagnosed with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma.

Research Highlights.

Few patients with early-stage uterine carcinosarcoma received adjuvant chemotherapy

Patterns of treatment did not change over the duration of the study period

Chemotherapy was not associated with an improved overall survival

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Branch, Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Science, NCI; the Office of Information Services, and the Office of Strategic Planning, HCFA; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Gunjal Garg, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Cecilia Yee, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA.

Kendra L. Schwartz, Department of Family Medicine and Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA.

David G. Mutch, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Robert T. Morris, Division of Gynecologic Oncology and Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA.

Matthew A. Powell, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO, USA.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prat J. FIGO staging for uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104:177–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Seshan VE, Schiff PB, Burke WM, Cohen CJ, et al. Uterine carcinosarcomas and grade 3 endometrioid cancers: evidence for distinct tumor behavior. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:64–70. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318176157c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen SN, Podratz KC, Scheithauer BW, O'Brien PC. Clinicopathologic analysis of uterine malignant mixed mullerian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;34:372–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leath CA, 3rd, Numnum TM, Kendrick JEt, Frederick PJ, Rocconi RP, Conner MG, et al. Patterns of failure for conservatively managed surgical stage I uterine carcinosarcoma: implications for adjuvant therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:888–91. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a831fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greer BE, Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum N, Bookman MA, Bristow RE, Campos SM, et al. Uterine Neoplasms. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:498–531. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfson AH, Brady MF, Rocereto T, Mannel RS, Lee YC, Futoran RJ, et al. A gynecologic oncology group randomized phase III trial of whole abdominal irradiation (WAI) vs. cisplatin-ifosfamide and mesna (CIM) as post-surgical therapy in stage I-IV carcinosarcoma (CS) of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.07.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright JD, Neugut AI, Wilde ET, Buono DL, Malin J, Tsai WY, et al. Physician characteristics and variability of erythropoiesis-stimulating agent use among Medicare patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:3408–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Legler JM. Assessing comorbidity using claims data: an overview. Med Care. 2002;40:IV–26–35. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–67. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silliman RA, Balducci L, Goodwin JS, Holmes FF, Leventhal EA. Breast cancer care in old age: what we know, don't know, and do. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:190–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gridelli C, Maione P, Rossi A, Ferrara ML, Castaldo V, Palazzolo G, et al. Treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly. Lung Cancer. 2009;66:282–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obeidat NA, Pradel FG, Zuckerman IH, DeLisle S, Mullins CD. Outcomes of irinotecan-based chemotherapy regimens in elderly Medicare patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:343–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Sharma DB, Gray SW, Chen AB, Weeks JC, Schrag D. Carboplatin and paclitaxel with vs without bevacizumab in older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA. 2012;307:1593–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nurgalieva Z, Liu CC, Du XL. Risk of hospitalizations associated with adverse effects of chemotherapy in a large community-based cohort of elderly women with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1314–21. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181b7662d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundararajan V, Hershman D, Grann VR, Jacobson JS, Neugut AI. Variations in the use of chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:173–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jatoi A, Hillman S, Stella P, Green E, Adjei A, Nair S, et al. Should elderly non-small-cell lung cancer patients be offered elderly-specific trials? Results of a pooled analysis from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9113–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenfield S, Blanco DM, Elashoff RM, Ganz PA. Patterns of care related to age of breast cancer patients. JAMA. 1987;257:2766–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samet J, Hunt WC, Key C, Humble CG, Goodwin JS. Choice of cancer therapy varies with age of patient. JAMA. 1986;255:3385–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovanazzi-Bannon S, Rademaker A, Lai G, Benson AB., 3rd Treatment tolerance of elderly cancer patients entered onto phase II clinical trials: an Illinois Cancer Center study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2447–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.11.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elston JM, Koch GG, Weissert WG. Regression-adjusted small area estimates of functional dependency in the noninstitutionalized American population age 65 and over. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:335–43. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. A population-based study of functional status and social support networks of elderly patients newly diagnosed with cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:366–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang K, Marciniak MD, Faries D, Stokes M, Buesching D, Earle C, et al. Trends and predictors of first-line chemotherapy use among elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. Lung Cancer. 2009;63:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsey SD, Howlader N, Etzioni RD, Donato B. Chemotherapy use, outcomes, and costs for older persons with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: evidence from surveillance, epidemiology and end results-Medicare. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4971–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omura GA, Major FJ, Blessing JA, Sedlacek TV, Thigpen JT, Creasman WT, et al. A randomized study of adriamycin with and without dimethyl triazenoimidazole carboxamide in advanced uterine sarcomas. Cancer. 1983;52:626–32. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830815)52:4<626::aid-cncr2820520409>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Fowler J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:36–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Nashar SA, Mariani A. Uterine carcinosarcoma. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:292–304. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31821ac635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton G, Brunetto VL, Kilgore L, Soper JT, McGehee R, Olt G, et al. A phase III trial of ifosfamide with or without cisplatin in carcinosarcoma of the uterus: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:147–53. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homesley HD, Filiaci V, Markman M, Bitterman P, Eaton L, Kilgore LC, et al. Phase III trial of ifosfamide with or without paclitaxel in advanced uterine carcinosarcoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:526–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoskins PJ, Le N, Ellard S, Lee U, Martin LA, Swenerton KD, et al. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel for advanced or recurrent uterine malignant mixed mullerian tumors. The British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantrell LA, Havrilesky L, Moore DT, O'Malley D, Liotta M, Secord AA, et al. A multi-institutional cohort study of adjuvant therapy in stage I-II uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed NS, Mangioni C, Malmstrom H, Scarfone G, Poveda A, Pecorelli S, et al. Phase III randomised study to evaluate the role of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine sarcomas stages I and II: an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group Study (protocol 55874) Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:808–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nout RA, Putter H, Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, Jobsen JJ, Lutgens LC, van der Steen-Banasik EM, et al. Quality of life after pelvic radiotherapy or vaginal brachytherapy for endometrial cancer: first results of the randomized PORTEC-2 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3547–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez Bosquet J, Terstriep SA, Cliby WA, Brown-Jones M, Kaur JS, Podratz KC, et al. The impact of multi-modal therapy on survival for uterine carcinosarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:419–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manolitsas TP, Wain GV, Williams KE, Freidlander M, Hacker NF. Multimodality therapy for patients with clinical Stage I and II malignant mixed Mullerian tumors of the uterus. Cancer. 2001;91:1437–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nemani D, Mitra N, Guo M, Lin L. Assessing the effects of lymphadenectomy and radiation therapy in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma: a SEER analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le T, Adolph A, Krepart GV, Lotocki R, Heywood MS. The benefits of comprehensive surgical staging in the management of early-stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:351–5. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]