Abstract

Artemether–lumefantrine (AL) became the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in Kenya in 2006. Studies have shown AL selects for SNPs in pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes in recurring parasites compared to the baseline infections. The genotypes associated with AL selection are K76 in pfcrt and N86, 184F and D1246 in pfmdr1. To assess the temporal change of these genotypes in western Kenya, 47 parasite isolates collected before (pre-ACT; 1995–2003) and 745 after (post-ACT; 2008–2014) introduction of AL were analyzed. In addition, the associations of parasite haplotype against the IC50 of artemether and lumefantrine, and clearance rates were determined. Parasite genomic DNA collected between 1995 and 2014 was analyzed by sequencing or PCR-based single-base extension on Sequenom MassARRAY. IC50s were determined for a subset of the samples. One hundred eighteen samples from 2013 to 2014 were from an efficacy trial of which 68 had clearance half-lives. Data revealed there were significant differences between pre-ACT and post-ACT genotypes at the four codons (chi-square analysis; p < 0.0001). The prevalence of pfcrt K76 and N86 increased from 6.4% in 1995–1996 to 93.2% in 2014 and 0.0% in 2002–2003 to 92.4% in 2014 respectively. Analysis of parasites carrying pure alleles of K + NFD or T + YYY haplotypes revealed that 100.0% of the pre-ACT parasites carried T + YYY and 99.3% of post-ACT parasites carried K + NFD. There was significant correlation (p = 0.04) between lumefantrine IC50 and polymorphism at pfmdr1 codon 184. There was no difference in parasite clearance half-lives based on genetic haplotype profiles. This study shows there is a significant change in parasite genotype, with key molecular determinants of AL selection almost reaching saturation. The implications of these findings are not clear since AL remains highly efficacious. However, there is need to closely monitor parasite genotypic, phenotypic and clinical dynamics in response to continued use of AL in western Kenya.

Keywords: Artemether–lumefantrine, Drug-resistance, Western Kenya, Artemisinin-based combination therapies, Africa, Chloroquine, Molecular markers, Genetics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The prevalence of pfcrt K76 increased from 6.4% in 1995 to 93.2% in 2014 and pfmdr1 N86 from 0% in 2002 to 92.4% in 2014.

-

•

100% of pre-ACTs parasites carried T+YYY haplotype whereas 99.3% post-ACTs parasites carried K+NFD haplotype.

-

•

There is resurgence of chloroquine sensitive parasite in western Kenya.

-

•

AL is still highly efficacious but there are drastic genetic changes taking place in the parasite population.

1. Introduction

Recent gains made in malaria control have relied on the sustained efficacy of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) which is the recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria by the World Health Organization (WHO). ACTs consist of a short-acting artemisinin component which rapidly reduces parasite biomass and results in consequent rapid resolution of the symptoms (Na et al., 1994; Bethel et al., 1997; White et al., 1999), and a long-acting partner drug (White et al., 1999) essential in clearing residual parasitemia. Resistance to ACTs is threatening malaria control and elimination efforts in Southeast Asia (SEA) (Noedl et al., 2008; Dondorp et al., 2009; WHO, 2014). However, ACTs remain highly efficacious in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with fast clearance half-lives (Ashley et al., 2014; Zwang et al., 2014). Sensitive P. falciparum parasites are cleared within 48 h in 95% of the patients post-ACTs treatment based on smears (White, 2008) whereas resistant parasites are characterized by slow clearance rates (Noedl et al., 2008; Dondorp et al., 2009). The presence of parasites at 72 h is a good predictor of subsequent treatment failure (Stepniewska et al., 2010). Mutations in the P. falciparum K13-propeller domain have recently been shown to be important determinants of artemisinin resistance in SEA (Ariey et al., 2014; Ashley et al., 2014). However, the K13-propeller region mutations recently described in SEA have not been found in African parasites (Ashley et al., 2014; Conrad et al., 2014; Kamau et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2014) nor has there been an association of K13 polymorphisms with parasite clearance half-lives in African parasites (Ashley et al., 2014).

The most commonly used ACT in SSA is artemether–lumefantrine (AL) (WHO, 2013) which has been used as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in Kenya since 2006 (Amin et al., 2007). In a recent study where individual patient data from 31 clinical trials was analyzed, the overall clinical efficacy for patients treated with AL was shown to be 94.8%; 93.8% efficacy in East Africa and 96.2% in West Africa (Venkatesan et al., 2014). In Kenya, AL efficacy has remained >95% (Ogutu et al., 2014). Although AL remains highly efficacious and K13 polymorphisms are not associated with reduced susceptibility to ACTs in SSA, AL is associated with selection of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter gene (pfcrt) and P. falciparum multidrug resistance gene 1 (pfmdr1) in parasite re-infections (Sisowath et al., 2005; Humphreys et al., 2007; Sisowath et al., 2007, 2009). The genotype associated with the parasite re-infection is the K76 in pfcrt and N86, 184F and D1246 (NFD) in the pfmdr1. Further, reduced susceptibility to lumefantrine has also been linked to NFD and increase in the pfmdr1 copy numbers (Lim et al., 2009; Some et al., 2010; Gadalla et al., 2011; Malmberg et al., 2013a,b). Recent meta-analysis of clinical trials data showed the presence of N86 allele and an increased pfmdr1 copy number were the most significant independent risk factors for recurrence of parasites in patients treated with AL (Venkatesan et al., 2014). Monitoring the selection and emergence of these markers presents a cost-effective method for detecting evidence of declines in parasite susceptibility to AL and should be made routine (Malmberg et al., 2013a,b; Venkatesan et al., 2014).

In 1998, sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) replaced chloroquine as the first-line treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Kenya due to treatment failure and in 2006, SP was replaced with AL (Shretta et al., 2000; Amin et al., 2007; Okiro et al., 2010). In both instances, treatment failures were attributed to development of drug resistance. The genotype associated with chloroquine resistance is pfcrt 76T (Djimdé et al., 2001), modulated by pfmdr1 86Y, Y184 and 1246Y (YYY) (Reed et al., 2000; Babiker et al., 2001). Interestingly, chloroquine resistant parasites are AL sensitive; i.e. AL selects for chloroquine sensitive parasites. In this study, we set out to analyze the temporal trends of parasite genotypes in pfcrt (codon 76) and pfmdr1 (codons 86, 184 and 1246) in parasite samples from Kisumu County, western Kenya, collected before (1995–2003) and after (2008–2014) introduction of AL, referred to as pre- and post-ACT respectively. The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) of artemether and lumefantrine in field isolates carrying combined pfcrt/pfmdr1 haplotype K + NFD were compared to those carrying haplotype T + YYY. Further, the association of parasite clearance rates with these haplotypes was investigated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

Samples used in this study were obtained from Kisumu County in pre- and post-ACT periods. Forty seven pre-ACT parasite samples were collected between 1995 and 2003 whereas 745 post-ACT parasites were collected between 2008 and 2014. Samples were collected under protocols approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Nairobi, Kenya and Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Institutional Review Board, Silver Spring, MD. The pre-ACT and post-ACT studies were conducted under approved study protocols KEMRI-SSC 1330/WRAIR 1384 (Epidemiology of malaria and drug sensitivity patterns in Kenya) and KEMRI-SSC 2518/WRAIR 1935 (In vivo and in vitro efficacy of artemisinin combination therapy in Kisumu County, western Kenya) respectively. KEMRI-SSC 2518/WRAIR 1935 efficacy study was conducted in Kombewa division, which is in Kisumu County, in 2013–2014. In both studies, patients presenting with uncomplicated malaria, aged between 6 months and 65 years were consented. Eligibility criteria included: measured temperature of ≥37.5 °C, a history of fever within 24 h prior to presentation, mono-infection with P. falciparum and a baseline parasitemia of 2000–200,000 asexual parasites/μL. Persons treated for malaria within the preceding 2 weeks were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from adult subjects (≥18 years of age) or legal guardians for subjects <18 years of age. The presence of malaria was confirmed by microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT; Parascreen®, Zephyr Biomedicals, Verna Goa, India). Whole blood was collected and aliquots preserved for analysis as specified in the study protocols. For KEMRI-SSC 1330/WRAIR 1384 protocol, subjects were treated with oral AL (Coartem) administered over three consecutive days, a standard of care for P. falciparum malaria in Kenya. The first dose was observed by the study team and remaining doses were self-administered at home. For KEMRI-SSC 2518/WRAIR 1935, subjects were admitted at the study facility for approximately 3 days, until two consecutive smear negative slides were obtained.

2.2. Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using QIAamp Blood mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Extracted DNA was stored appropriately until analyzed. Pfcrt K76T and pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F and D1246Y alleles were determined by sequencing or PCR-based single-base extension on Sequenom MassARRAY platform (Agena Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) following manufacturer recommendations. Previously published primers for pfcrt K76T (Djimdé et al., 2001) and pfmdr1 SNPs (Vinayak et al., 2010) were used for PCR and sequencing analyses. The final concentration of PCR reactants were as follows: 0.5 μM each of the primers, 1× PCR buffer, 4 mM of magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 0.02 Units of Taq polymerase, 100 μM (25 μM each) of deoxynucleotides. After successfully amplifying the target regions, the isolates were purified using Exosap-it® (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Sequencing of the target regions was done on the 3500 xL ABI Genetic analyzer using version 3.1 of the big dye terminator method (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Contig assembly of the generated sequences was performed using CLC Bio Workbench 6 and the sequences aligned and analyzed using BioEdit version 7.1.3.0. All sequences were compared against the pfcrt (Accession Number; XM_001348968) and pfmdr1 (Accession Number; XM_001351751) 3D7 reference sequence published in the NCBI database.

2.3. In vitro drug susceptibility testing

The drugs used for the in vitro testing were artemether and lumefantrine which were supplied by the Division of Experimental Therapeutics of the WRAIR. Parasites were maintained in continuous culture as previously described (Trager and Jensen, 1976). SYBR Green I- based drug sensitivity assay was used for the in vitro drug sensitivity testing as previously published (Bacon et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2007; Rason et al., 2008). P. falciparum parasites in continuous culture attaining 3%–8% parasitemia were adjusted to 2% hematocrit and 1% parasitemia. Blood samples with >1% parasitemia were adjusted to 1% parasitemia at 2% hematocrit, and those with ≤1% parasitemia were used unadjusted at 2% hematocrit.

Drugs were prepared in 5 mL of 99.5% dimethyl sulfoxide to attain 5 mg/mL which were lowered to starting concentrations of 690 nM for AT and 378 nM for LU. This was followed by serial dilution across 10-concentrations ranging from (in nM) AT 670 to 0.65 and LU 378 to 0.37. For drug assaying, 3.2 μL of this drug was coated on to 384-well plates. The assay was initiated by the addition of 100 μL reconstituted parasite components added to drug coated plates and incubated at 37 °C as previously described (Bacon et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2007; Rason et al., 2008). The assay was terminated after 72 h by adding 100 μL of lysis buffer containing SYBR Green I (1× final concentration) directly to the plates and kept at room temperature in the dark for 24 h. Parasite replication inhibition was quantified by measuring the per-well relative fluorescence units (RFU) of SYBR Green I dye using the Tecan Genios Plus® with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 535 nm. The IC50 values for each drug were calculated as previously described (Johnson et al., 2007).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Changes in prevalence of pfcrt and pfmdr1 individual SNPs and the combined haplotype pre- and post-ACT were analyzed using chi-square test for proportions and logistic regression with year included as a continuous covariate respectively. The odds ratios (OR) analysis was done using STATA version 11 (Stata, College Station, TX); OR were used to calculate the relative change of parasite genotype and the IC50s per year. Chi-square analysis was used to compare change in the prevalence of genotypes. This was done using the Prism program (version 5.0.2; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). The IC50 estimates were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Further, IC50 data for isolates with the different genetic polymorphism in pfcrt and pfmdr1 were compared by using nonparametric tests (1-way analysis of variance, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison post test). Associations between IC50 estimates and genetic markers were considered significant when p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of SNPs in pre- and post-ACT parasites

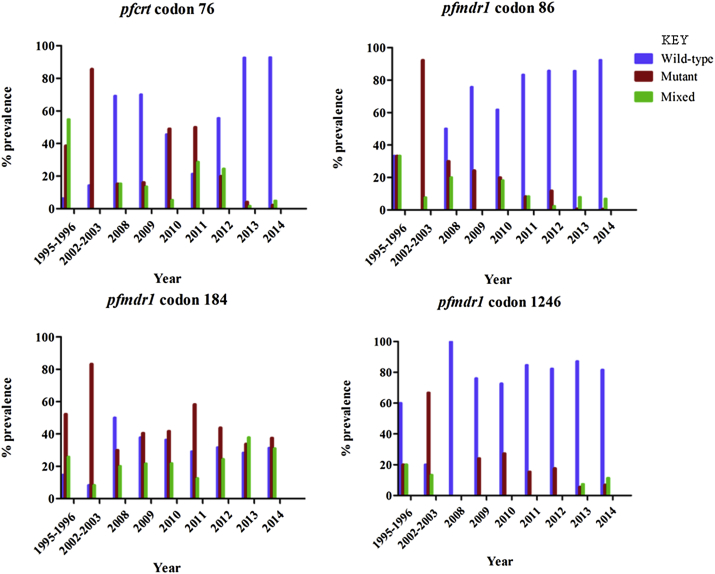

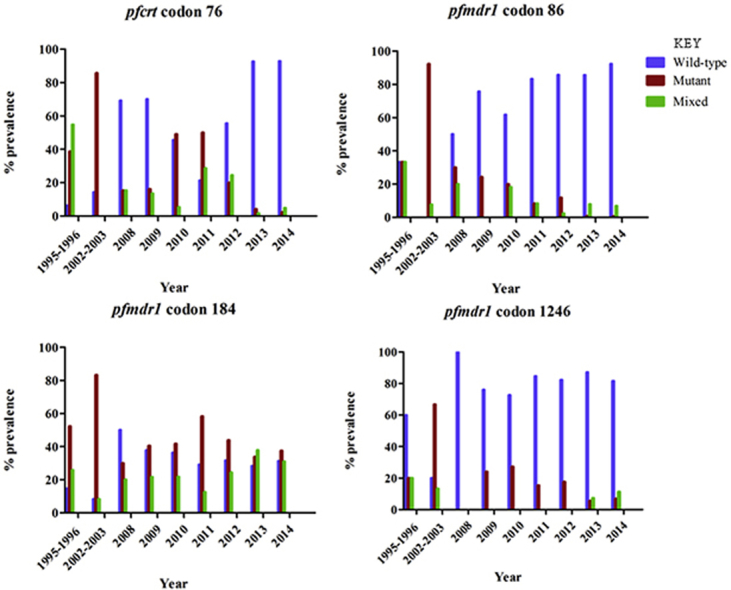

A total of 792 field isolates collected from the study sites between 1995 and 2014 were successfully analyzed. There were 47 pre-ACT (1995–2003) samples and 745 post-ACT (2008–2014) samples analyzed; the pre-ACT sample size was significantly smaller than the post-ACT. For the post-ACT samples, 118 were from an efficacy study, of which 68 had parasite clearance half-life data and were used in subsequent analysis. Four SNPs were genotyped: Pfcrt 76 and pfmdr1 86, 184 and 1246. Analysis was performed for pre-ACT and post-ACT parasites, revealing statistically significant difference between pre- and post-ACT genotypes at the four codons (chi-square analysis; p < 0.0001). Data revealed that the mean prevalence of the wild-type allele in pfcrt codon 76 (K76) in pre-ACT parasites was 10.4% and 61.7% post-ACT, whereas the mean prevalence for the mutant allele in pfcrt codon 76 (76T) in pre-ACT parasites was 62.2% and 28.5% in post-ACT. In pre-ACT parasites, 27.4% carried the mixed genotype whereas in post-ACT, 9.8% carried the mixed genotype. Further analysis revealed K76 prevalence was lowest in 1995–1996 at 6.4% and highest in 2014 at 93.2% whereas 76T was highest in 2002–2003 at 85.7% and lowest in 2014 at 2.3%.

For the wild-type allele in pfmdr1 codon 86 (N86), the mean prevalence in pre-ACT parasites was 16.7% and 73.0% in post-ACT whereas the mean prevalence for the mutant allele in pfmdr1 codon 86 (86Y) in pre-ACT parasites was 62.8% and 14.9% in post-ACT. The prevalence of mixed genotype was 20.5% and 11.4% in pre- and post-ACT parasites respectively. Further, data revealed N86 prevalence was lowest in 2002–2003 at 0.0% and highest in 2014 at 92.4%, whereas 86Y was highest in 2002–2003 at 92.3% and lowest in 2014 at 0.7%.

The mean prevalence of the wild-type allele in pfmdr1 codon 184 (Y184) in pre-ACT parasites was 11.6% and 35.0% in post-ACT whereas the mean prevalence for the mutant allele in pfmdr1 codon 184 (184F) in pre-ACT parasites was 67.8% and 40.8% in post-ACT. The prevalence of the mixed genotype was 17.1% and 24.2% in pre- and post-ACT parasites respectively. Further, data revealed Y184 prevalence was lowest in 2002–2003 at 8.3% and highest in 2008 at 50.0% whereas prevalence of 184F was highest in 2002–2003 at 83.3% and lowest in 2008 at 30.0%.

The mean prevalence of the wild-type allele in pfmdr1 codon 1246 (D1246) in pre-ACT parasites was 40.0% and 83.5% in post-ACT whereas the mean prevalence for the mutant allele in pfmdr1 codon 1246 (1246Y) in pre-ACT parasites was 43.4% and 13.8% in post-ACT. The prevalence of mixed genotype was 16.7% and 2.7% in pre- and post-ACT parasites respectively. Further, data revealed D1246 prevalence was lowest in 2002–2003 at 20.0% and highest in 2008 at 100.0% whereas prevalence of 1246Y was highest in 2002–2003 at 66.7% and lowest in 2013 at 5.5%.

3.2. Prevalence of K + NFD and T + YYY haplotypes

Parasite haplotypes at codon 76 in pfcrt and codons 86, 184 and 1246 in pfmdr1 were evaluated. Data in all the four codons were obtained in 499 samples (70.2%) where 28 were pre-ACT and 471 post-ACT. Further, we analyzed K + NFD and T + YYY haplotypes. There were 142 parasite samples carrying K + NFD or T + YYY haplotype; 132 were K + NFD and 10 were T + YYY (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of parasites carrying K + NFD versus T + YYY haplotype from 1995 to 2014.

| 1995–1996 n (%) |

2002–2003 n (%) |

2008 n (%) |

2009 n (%) |

2010 n (%) |

2011 n (%) |

2012 n (%) |

2013 n (%) |

2014 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K + NFD | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (14.3) | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (19.0) | 29 (16.6) | 81 (27.7) |

| T + YYY | 2 (6.5) | 7 (20.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

3.3. Temporal trends of SNPs in pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes

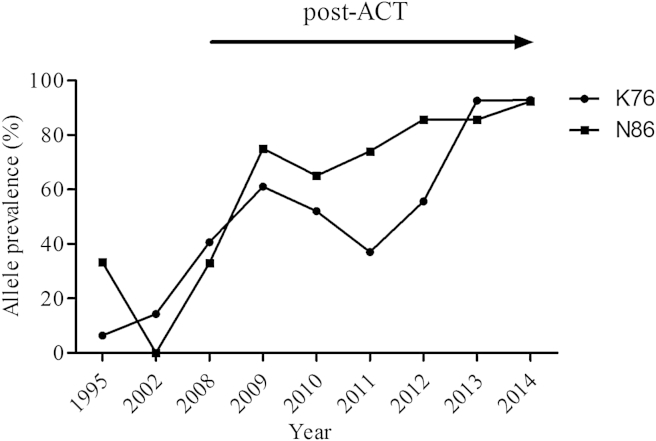

Fig. 1 shows the temporal trend of SNPs in pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes from 1995 to 2014. The prevalence of pfcrt K76 increased from 6.4% in 1995–1996 to 93.2% in 2014 (Fig. 2). There was a steady increase over the 20-year period from 10.4% in pre-ACT parasites to 61.7% in post-ACT (yearly OR = 0.67 [95% CI 0.60 − 0.74; p < 0.001]). The mutant allele, pfcrt 76T was highest in 2002–2003 at 85.7%, decreasing to 2.3% in 2014. In 1995–1996, the majority of the parasites carried mixed alleles (54.8%) whereas in 2014, only 4.9% carried mixed genotype. In post-ACT, parasites collected in 2010, 2011 and 2012 had low prevalence of the pfcrt K76, with 2011 having the lowest prevalence at 37.0%. Interestingly, in 2013 and 2014, the prevalence of pfcrt K76 increased significantly to more than twice the previous year (2012), reaching 92.9% in 2014.

Fig. 1.

The prevalence of SNP in the pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes in the pre- and the post-ACTs parasite samples.

Fig. 2.

The temporal trends of the pfcrt K76 and pfmdr1 N86 alleles in the pre- and the post-ACT periods (1995–2014). The percent prevalence of parasite samples carrying either K76 or N86 genotype over the years. The arrow indicates the post-ACT period.

The wild-type allele in pfmdr1 codon 86 increased from 33.3% in 1995–1996 to 92.4% in 2014 (Fig. 2). This increment was steady over the 20-year period from 16.7% in pre-ACT parasites to 72.0% in post-ACT (yearly OR = 0.76 [95% CI 0.72 − 0.82; p < 0.0001]). The mutant allele, pfcrt 86Y was highest in 2002–2003 at 92.3%, decreasing to 0.7% in 2014; there was no single parasite carrying the wild-type allele in 2002–2003. The highest percentage of the mixed alleles was in found 1995–1996 parasites at 33.3%, decreasing to 6.9% in 2014. The wild-type allele in pfmdr1 codon 184 increased from 14.8% in 1995–1996 to 31.4% in 2014. The highest prevalence of pfmdr1 Y184 was in 2008 at 50.0% which was followed by a downward trend reaching 31.4% in 2014. The highest prevalence of the mutant allele pfmdr1 184F was in 2002–2003 at 83.3% and lowest in 2008 at 30.0%. There was a steady increase of the mixed genotype at codon 184 from 20.0% in 2008 to 33.1% in 2014. With exception of 2008, the prevalence of pfmdr1 184F remained higher than pfmdr1 Y184 in all post-ACT parasites (yearly OR = 1.1 [95% CI 1.04 − 1.16; p < 0.001]).

The wild-type allele in pfmdr1 codon 1246 increased from 60.0% in 1995–1996 to 81.6% in 2014 (yearly OR = 0.87 [95% CI 0.83 − 0.92; p < 0.001]). The prevalence of the mutant allele, pfmdr1 1246Y was highest in 2002–2003 at 66.7% and lowest in 2008 at 0.0%. However, the prevalence of the mutant allele rebounded back in 2009 at 24.0% but steadily declined over time reaching 6.9% in 2014. There were no mixed genotypes between 2008 and 2012.

3.4. Temporal trends of K + NFD and T + YYY haplotypes in pre- and post-ACT parasites

Of the 28 pre-ACT parasite samples with complete genotype data at codon pfcrt 76 and codons pfmdr1 86, 184 and 1246, analysis of parasite samples carrying pure alleles of K + NFD or T + YYY haplotypes revealed that 100.0% of the pre-ACT parasite samples carried the T + YYY (n = 9). In post-ACT parasite samples, of the 471 parasite samples successfully analyzed at all the codons, 28.2% (n = 133) of the parasite samples carried K + NFD haplotype whereas only 0.2% (n = 1) carried T + YYY haplotype; the single T + YYY haplotype in post-ACT parasite samples was present in 2012 (Table 1). K + NYD haplotype was not present in pre-ACT parasite samples but appeared in the post-ACT parasite samples, increasing significantly in 2013–2014; there were 3 parasite samples in 2009, 2 in 2011, 41 in 2013 and 67 in 2014 carrying this haplotype. Other haplotypes of interest analyzed include those carrying the mixed allele at pfcrt 76 and pure single alleles at pfmdr1 84, 186 and 1246. For example, there was one pre-ACT parasite sample that carried K/T + NFD and eight in post-ACT parasite samples, and two parasite samples in 2009 that carried K/T + YYY. Mixed alleles at all the four codons were present only in pre-ACT parasite samples.

3.5. Associations of in vitro sensitivity with pfcrt and pfmdr1 polymorphisms

Artemether and lumefantrine IC50 values for the two reference strains, 3D7 and W2, were established and used as internal controls in subsequent experiments. The IC50 data was obtained for a total of 187 field isolates with genotype data at any one of the four codons. The profile for in vitro sensitivities per genetic polymorphism in all the four codons was assessed. At each codon, the correlation of the IC50s (for artemether and lumefantrine) were done for parasites carrying the wild-type, mutant or mixed alleles. For the pfcrt codon 76, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) of artemether IC50 for parasites carrying K76, 76T or K76T alleles were 3.2 nM (1.6–6.4 nM), 3.5 nM (2.4–9.5 nM) and 5.0 nM (2.6–12.5 nM), respectively. Although K76T had a slightly higher median IC50, the difference did not reach statistical significance (1-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test p = 0.06). Similarly, the difference in IC50s for lumefantrine between the three different pfcrt genotypes did not reach statistical difference (p = 0.29). Analysis of the pfmdr1 revealed there was significant correlation (1-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test p = 0.04) between lumefantrine IC50 and polymorphism at codon 184. The median (IQR) lumefantrine IC50s for parasites carrying Y184, 184F or Y184F alleles were 25.8 (11.2–43.2), 27.0 (11.9–59.5) and 12.0 (4.8–39.3), respectively. Dunn's multiple comparison test revealed the significance was between IC50s for parasites carrying 184F vs. Y184F. There was no other genotype in pfmdr1 that showed any correlation with either artemether or lumefantrine.

3.6. Associations of parasite clearance rates with pfcrt and pfmdr1 polymorphisms

Clearance half-lives were obtained for the 68 subjects with complete parasite haplotype profiles. Five different parasite haplotype profiles were analyzed including K + NFD, K + NYD, K + N Y/F D, K + N Y/F D/Y and all other profiles combined that did not fall to any of the indicated haplotype profiles. There was no difference in the parasite clearance half-lives based on genetic haplotype profiles (1-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.61).

4. Discussion

The data shows a dramatic change in the prevalence of antimalarial molecular markers associated with changes in chloroquine drug pressure and deployment of AL in western Kenya. The significant changes are in the prevalence of the wild-type alleles in pfcrt codon 76, and pfmdr1 codons 86 and 1246 between pre-ACT and the post-ACT era which coincided with withdrawal of chloroquine and the introduction of AL. The pfcrt K76 and pfmdr1 N86 alleles had the most dramatic increase in prevalence reaching to more than 92% in the post-ACT period from low points of 6.4% and 0.0% respectively in the pre-ACT period. Conversely, pfcrt 76T and pfmdr1 86Y prevalence dramatically decreased 38- and 128-fold respectively from the highest point in the pre-ACT period to the lowest point in the post-ACT period. The prevalence of mixed genotypes in these two codons decreased as well. The pfmdr1 D1246 also had dramatic change, increasing to a prevalence of 87.2% in 2013. Conversely, the prevalence of pfmdr1 1246Y decreased to 5.5% in 2013. The mixed genotype decreased from the pre-ACT period to the post-ACT period. The prevalence of pfmdr1 Y184 allele and the mixed genotype increased in the post-ACT parasites compared to the pre-ACT parasites. Interestingly, haplotype analysis revealed the pre-ACT parasites carried only T + YYY haplotype whereas the post-ACT parasites, with exception of one parasite (1 out of 133), carried the K + NFD haplotype. Of interest was the K + NYD (wild-type in all the four alleles) which appeared in the post-ACT parasites, increasing dramatically in 2013 and 2014. Our data also revealed that there was a significant correlation between lumefantrine IC50 with polymorphisms at pfmdr1 codon 184. However, there was no association between parasite clearance rates with polymorphisms at codons in pfcrt or pfmdr1 genes.

In line with previous studies (Kublin et al., 2003; Laufer et al., 2010; Eyase et al., 2013; Okombo et al., 2014) we have shown there was selection of the pfcrt K76 after change of drug policy. Removal of chloroquine drug pressure results in resurgence of chloroquine sensitive parasite population. In Malawi, the reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum malaria parasites reached 100% in less than 10 years after chloroquine was replaced with SP (Kublin et al., 2003). In our study, there was evidence of dramatic resurgence (p < 0.001) of the pfcrt K76 in 2008, 2 years after introduction of AL and close to 10 years after withdraw of chloroquine. However, in 2002–2003, about 5 years after withdrawal of chloroquine and introduction of SP, the pfcrt K76 had not dramatically resurged. In the Kenyan coastal region, studies have revealed a significant decrease of the pfcrt 76T after the withdrawal of chloroquine. In samples analyzed from Kilifi (which is in the coastal region of Kenya), the pfcrt 76T decreased from 94% to 63% from 1993 to 2006 and in a study conducted in Tiwi which is also at the Kenyan coast, the pfcrt 76T decreased from 88% to 64% from 1999 to 2008 (Mwai et al., 2009; Mang'era et al., 2012). In a more recent study which also used samples from Kilifi, there was a more drastic change in the pfcrt 76T from 96% in 1999 to 15% in 2012/2013 (Okombo et al., 2014). In our study, we saw a more dramatic drop of the pfcrt 76T from a high of 85.7% in 2002/2003 to 2.3% in 2014. This is the lowest reported prevalence of the pfcrt 76T in Kenya. At the same time, Okombo et al. (2014) reported significance resurgence of the pfcrt K76 in Kilifi from 38% in 1995 to 81.7% in 2012/2013. In our study, the pfcrt K76 resurged from 6.4% to 92.9% in 2014. There is obvious significant resurgence of the pfcrt K76 in Kenyan parasites after the withdrawal of chloroquine. The rate of change in the pfcrt K76 is not related to transmission intensity as the changes are almost identical between western and coastal regions of Kenya which have different transmission and disease endemicity. A recent study from western Kenya showed a directional selection of the pfcrt K76 after treatment of patients with AL (Henriques et al., 2014). Our data demonstrates that after the removal of chloroquine pressure on the parasite population, there was a loss of the pfcrt 76T genotype but at a slow rate with the introduction of SP. AL was adopted as the first-line treatment in Kenya in 2006 (Amin et al., 2007). The frequency of the pfcrt 76T allele decreased after the introduction of AL but it is not until the 2013/2014 time-frame that there was a dramatic loss of the pfcrt 76T allele which can be attributed to continued selection of the pfcrt K76 allele by AL.

A recent pooled analysis from clinical trials showed patients infected with parasites carrying the pfmdr1 N86 allele and/or increased the pfmdr1 copy number (as independent risk factors) were at a significantly greater risk of AL treatment failure than those whose parasites carried the 86Y allele or a single copy of the pfmdr1 (Venkatesan et al., 2014). In a recent study where we analyzed the presence and distribution of the copy number variation of the pfmdr1 gene in the pre- and the post-ACT parasites, seven of eight parasite samples with multiple pfmdr1 gene copy number were the post-ACT (Ngala et al., 2015). We also showed that the post-ACT parasites had significantly higher pfmdr1 gene copy number compared to the pre-ACT parasites (p = 0.0002). There was an overlap in the parasite samples analyzed in this study and the Ngalah et al. (2015) study. Although the pfmdr1 gene amplification is rarely reported in African parasites (Uhlemann et al., 2005; Holmgren et al., 2006), a recent efficacy study showed amplification of the pfmdr1 gene contributes to recurrent P. falciparum parasitemia following AL treatment (Gadalla et al., 2011). In this study, we have shown dramatic increase of the pfmdr1 N86 from 0.0% in 2002/2003 to reaching over 92% in 2014 and the pfmdr1 86Y decreasing to less than 1% in 2014. This data presents evidence of strong selection of the pfmdr1 N86 allele, as well as increased pfmdr1 gene copy number in the post-ACT parasites which is rarely reported in African parasites. The increased prevalence of the N86 allele and the pfmdr1 gene copy number are the most significant independent risk factors for recurrence of parasites in patients treated with AL (Venkatesan et al., 2014). Although adequate clinical and parasitological response to ACTs remain high in western Kenya (Ogutu et al., 2014), data suggest there is underlying selection of parasites taking place (Henriques et al., 2014) which might result in decreased parasite susceptibility to AL. Indeed, re-infecting parasites carrying the pfmdr1 N86 have been shown to withstand lumefantrine 35-fold higher compared to those carrying the pfmdr1 86Y (Malmberg et al., 2013a). To the best of our knowledge, our data shows the highest prevalence of the pfmdr1 N86 and increase of pfmdr1 gene copy number that has ever been reported for western Kenya parasites.

In line with previous studies (Sisowath et al., 2007; Malmberg et al., 2013a,b), we showed there was also a significant increase of the pfmdr1 D1246 in the post-ACT parasites compared to the pre-ACT parasites. In the post-ACT parasites, the pfmdr1 184F allele trend remained relatively constant but the mixed allele, pfmdr1 Y184F significantly increased over time. Interestingly, when we analyzed the association of the in vitro parasites sensitivity with the pfcrt and pfmdr1 polymorphisms, only polymorphisms at the pfmdr1 codon 184 showed significant association with lumefantrine IC50. The clinical relevance of this finding is not clear but provides a basis to support close monitoring of parasite clearance in western Kenya since development of resistance to antimalarials is a dynamic process. In a study that assessed patient lumefantrine drug level and its association with the pfmdr1 polymorphisms, the influence of polymorphisms at codon 184 was not clear since parasites carrying the Y184 allele, which is considered to be “sensitive”, were able to withstand high drug levels (Malmberg et al. 2013a).

The haplotype K + NFD has been shown to appear following AL treatment (Sisowath et al., 2005, 2007, 2009). In line with previous studies (Malmberg et al., 2013a,b; Okombo et al., 2014) K + NFD haplotype increased significantly in the post-ACT period. The haplotype T + YYY appeared only in the pre-ACT parasite samples and not in the post-ACT. Of interest was the appearance of the K + NYD haplotype which was not present in pre-ACT parasite samples but appeared and increased significantly longitudinally in the post-ACT parasite samples. This is also in line with the recent study by (Okombo et al., 2014) where they showed significant increase of the K + NYD haplotype over time. Malmberg et al. (2013a,b) showed a trend of decreasing lumefantrine susceptibility in the order of NFD, NYD, YYY, and YYD. Our data present evidence that strong selection of these haplotypes is taking place in western Kenya due to use of AL. Interestingly, recent studies suggested selection for the NFD haplotype is exerted by the artemisinin component of the ACTs (Conrad et al., 2014; Henriques et al., 2014). Clear evidence has shown these selected haplotypes have decreased susceptibility to lumefantrine (Malmberg et al., 2013a,b) but no such evidence has been presented for artemisinin component for the ACTs. Whether selection of these genotypes will lead to reduced susceptibility to AL remains to be seen but calls for close monitoring.

Although polymorphisms at the pfmdr1 codons 86, 184, 1034, 1042, 1246 are associated with altered sensitivity to artemisinins and mefloquine in SEA, the key determinant has been shown to be the copy number variation (Cowman et al., 1994; Price et al., 1999; Duraisingh et al., 2000; Price et al., 2004; Sidhu et al., 2005; Picot et al., 2009; Muhamad et al., 2011). Further, the discovery of mutations in K13-propeller in SEA but not in African parasites shows the multigenetic nature of artemisinin resistance in different parts of the world. AL and other ACTs remain highly efficacious in SSA including western Kenya (Ogutu et al., 2014; Venkatesan et al., 2014). Whether selection of haplotype K + NFD or K + NYD signifies apparent selection of AL resistant parasite is yet to be confirmed. Even with the emergence and spread of ACTs resistant parasites in SEA, ACTs remain the first-line treatment in this region. The pfcrt K76 allele and pfmdr1 N86 might soon reach saturation at 100% prevalence in western Kenya. Further, for the first-time in western Kenya, we have shown the prevalence of pfmdr1 copy number is on the rise. The apparent recent increase in these molecular markers should be a cause to rethink the issue with the deployment of first-line treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Although in vivo efficacy of AL remains >95%, the malaria community should start thinking of strategies of deploying other ACTs that are currently available to ensure a longer useful therapeutic lifespan before other new molecules are available in the market.

With the prevalence of pfcrt K76 allele well above 90%, a clear re-emergence of chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum malaria in western Kenya, there is need to evaluate the role of chloroquine or compounds in the same class in the treatment of malaria. This is supported by the current molecular data that unambiguously show genetic polymorphisms in pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes are changing in favor of chloroquine sensitivity.

Based on our findings and data from other studies (Kublin et al., 2003; Laufer et al., 2010; Gadalla et al., 2011; Eyase et al., 2013; Malmberg et al., 2013a,b; Henriques et al., 2014; Ogutu et al., 2014; Okombo et al., 2014; Venkatesan et al., 2014), more studies are required to determine the genotypic or phenotypic parasite characteristics that are directly associated with artemisinin resistance. Further, studies on how to mitigate the emergence and spread of parasites that are resistance to ACTs are critical in SSA where majority of the deaths due to malaria occur.

5. Conclusion

We have shown significant increase in polymorphisms at key codons in the pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes that are selected for by AL and decrease of these key codons with the withdrawal of chloroquine. This is exemplified by the high prevalence of the K + NFD haplotype which although associated with reduced susceptibility to AL, is generally linked to increased susceptibility to chloroquine and amodiaquine (Humphreys et al., 2007). There was no association between parasite clearance rates and the pfcrt and pfmdr1 polymorphisms. The findings call for close monitoring of parasite genotypic, phenotypic and clinical dynamics in response to current first-line treatment in western Kenya. Having been the first focus of chloroquine resistance in Africa (Fogh et al., 1979), western Kenya will be crucial in informing the next steps on the deployment of first-line treatment of uncomplicated malaria in the possible future era of attenuated response of artemisinin in SSA.

Author contributions statement

A.O.A Performed experiments, data analysis, manuscript writing. P.M. Performed experiments. L.A.I. Performed experiments, data analysis. B.H.O. Performed experiments. D.W.J. Data analysis. R.Y. Performed experiments. B.S.N. Contributed data. B.R.O. Manuscript writing and review. B.A. Study PI, data analysis, manuscript review. H.M.A. Project design, data analysis, manuscript review. E.K. Conceived and design project, data analysis, manuscript writing.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients, clinical and other support staff at the study sites. We are grateful to our colleagues in the Malaria Drug Resistance laboratory for their technical and moral support. We would also like to thank the Director of KEMRI for permission to publish this work. This work was supported by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, Division of Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System Operations. The opinions and assertions contained herein are private opinions of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army Medical Research Unit-Kenya, the U.S. Department of the Army, the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

- Amin A.A., Zurovac D., Kangwana B.B., Greenfield J., Otieno D.N., Akhwale W.S., Snow R.W. The challenges of changing national malaria drug policy to artemisinin-based combinations in Kenya. Malar. J. 2007;6:72. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariey F., Witkowski B., Amaratunga C., Beghain J., Langlois A.C., Khim N., Kim S., Duru V., Bouchier C., Ma L., Lim P., Leang R., Duong S., Streng S., Suon S., Chuor C.M., Bout D.M., Menard S., Rogers W.O., Genton B., Fandeur T., Miotto O., Ringwald P., Le Bras J., Berry A., Barale J.C., Fairhurst R.M., Benoit-vical F., Mercereau-Puijalon O., Menard D. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley E.A., Dhorda M., Fairhurst R.M., Amaratunga C., Lim P., Suon S., Sreng S., Anderson J.M., Mao S., Sam B., Sopha C., Chuor C.M., Nguon C., Sovannaroth S., Pukrittayakamee S., Jittamala P., Chotivanich K., Chutasmit K., Suchatsoonthorn C., Runcharoen R., Hien T.T., Thuy-Nhien N.T., Thanh N.V., Phu N.H., Htut Y., Han K.T., Aye K.H., Mokuolu O.A., Olaosebikan R.R., Folaranmi O.O., Mayxay M., Khanthavong M., Hongvanthong B., Newton P.N., Onyamboko M.A., Fanello C.I., Tshefu A.K., Mishra N., Valecha N., Phyo A.P., Nosten F., Yi P., Tripura R., Borrmann S., Bashraheil M., Peshu J., Faiz M.A., Ghose A., Hossain M.A., Samad R., Rahman M.R., Hasan M.M., Islam A., Miotto O., Amato R., MacInnis B., Stalker J., Kwiatkowski D.P., Bozdech Z., Jeeyapant A., Cheah P.Y., Sakulthaew T., Chalk J., Intharabut B., Silamut K., Lee S.J., Vihokhern B., Kunasol C., Imwong M., Tarning J., Taylor W.J., Yeung S., Woodrow C.J., Flegg J.A., Das D., Smith J., Venkatesan M., Plowe C.V., Stepniewska K., Guerin P.J., Dondorp A.M., Day N.P., White N.J. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:411–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiker H.A., Pringle S.J., Abdel-Muhsin A., Mackinnon M., Hunt P., Walliker D. High-level chloroquine resistance in Sudanese isolates of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with mutations in the chloroquine resistance transporter gene pfcrt and the multidrug resistance Gene pfmdr1. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;183:1535–1538. doi: 10.1086/320195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon D.J., Latour C., Lucas C., Colina O., Ringwald P., Picot S. Comparison of a SYBR green I-based assay with a histidine-rich protein II enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for in vitro antimalarial drug efficacy testing and application to clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1172–1178. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01313-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell D.B., Teja-Isavadharm P., Cao X.T., Pham T.T., Ta T.T., Tran T.N., Nguyen T.T., Pham T.P., Kyle D., Day N.P., White N.J. Pharmacokinetics of oral artesunate in children with moderately severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997;91:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad M.D., LeClair N., Arinaitwe E., Wanzira H., Kakuru A., Bigira V., Muhindo M., Kamya M.R., Tappero J.W., Greenhouse B., Dorsey G., Rosenthal P.J. Comparative impacts over 5 years of artemisinin-based combination therapies on Plasmodium falciparum polymorphisms that modulate drug sensitivity in Ugandan children. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210:344–353. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowman A.F., Galatis D., Thompson J.K. Selection for mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is linked to amplification of the pfmdr1 gene and cross-resistance to halofantrine and quinine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:1143–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djimdé A., Doumbo O.K., Cortese J.F., Kayentao K., Doumbo S., Diourté Y., Coulibaly D., Dicko A., Su X.Z., Nomura T., Fidock D.A., Wellems T.E., Plowe C.V. A molecular marker for chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:257–263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp A.M., Nosten F., Yi P., Das D., Phyo A.P., Tarning J., Lwin K.M., Ariey F., Hanpithakpong W., Lee S.J., Ringwald P., Silamut K., Imwong M., Chotivanich K., Lim P., Herdman T., An S.S., Yeung S., Singhasivanon P., Day N.P., Lindegardh N., Socheat D., White N.J. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraisingh M.T., Roper C., Walliker D., Warhurst D.C. Increased sensitivity to the antimalarials mefloquine and artemisinin is conferred by mutations in the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:955–961. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyase F.L., Akala H.M., Ingasia L., Cheruiyot A., Omondi A., Okudo C., Juma D., Yeda R., Andagalu B., Wanja E., Kamau E., Schnabel D., Bulimo W., Waters N.C., Walsh D.S., Johnson J.D. The role of Pfmdr1 and Pfcrt in changing chloroquine, amodiaquine, mefloquine and lumefantrine susceptibility in western-Kenya P. falciparum samples during 2008–2011. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogh S., Jepsen S., Effersoe P. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Kenya. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1979;73:228–229. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla N.B., Adam I., Elzaki S.E., Bashir S., Mukhtar I., Oguike M., Gadalla A., Mansour F., Warhurst D., El-Sayed B.B., Sutherland C.J. Increased pfmdr1 copy number and sequence polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Sudanese malaria patients treated with artemether-lumefantrine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5408–5411. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05102-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques G., Hallett R.L., Beshir K.B., Gadalla N.B., Johnson R.E., Johnson R.E., Burrow R., van Schalkwyk D.A., Sawa P., Omar S.A., Clark T.G., Bousema T., Sutherland C.J. Directional selection at the pfmdr1, pfcrt, pfubp1 and pfap2mu loci of Plasmodium falciparum in Kenyan children treated with ACT. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210:2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren G., Björkman A., Gil J.P. Amodiaquine resistance is not related to rare findings of pfmdr1 gene amplifications in Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2006;11(12):1808–1812. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys G.S., Merinopoulos I., Ahmed J., Whitty C.J., Mutabingwa T.K., Sutherland C.J., Hallett R.L. Amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine select distinct alleles of the Plasmodium falciparum mdr1 gene in Tanzanian children treated for uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:991–997. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00875-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.D., Dennull R.A., Gerena L., Lopez-Sanchez M., Roncal N.E., Waters N.C. Assessment and continued validation of the malaria SYBR Green I-based fluorescence assay for use in malaria drug screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1926–1933. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01607-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamau E., Campino S., Amenga-Etego L., Drury E., Ishengoma D., Johnson K., Mumba D., Kekre M., Yavo W., Mead D., Bouyou-Akotet M., Apinjoh T., Golassa L., Randrianarivelojosia M., Andagalu B., Maiga-Ascofare O., Amambua-Ngwa A., Tindana P., Ghansah A., MacInnis B., Kwiatkowski D., Djimde A.A. K13-Propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;211:1352–1355. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kublin J.G., Cortese J.F., Njunju E.M., Mukadam R.A., Wirima J.J., Kazembe P.N., Djimdé A.A., Kouriba B., Taylor T.E., Plowe C.V. Reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum malaria after Cessation of chloroquine use in Malawi. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(12):1870–1875. doi: 10.1086/375419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer M.K., Takala-Harrison S., Dzinjalamala F.K., Stine O.C., Taylor T.E., Plowe C.V. Return of chloroquine-susceptible falciparum malaria in Malawi was a reexpansion of diverse susceptible parasites. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202:801–808. doi: 10.1086/655659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P., Alker A.P., Khim N., Shah N.K., Incardona S., Doung S., Yi P., Bouth D.M., Bouchier C., Puijalon O.M., Meshnick S.R., Wongsrichanalai C., Fandeur T., Le B.J., Ringwald P., Ariey F. Pfmdr1 copy number and arteminisin derivatives combination therapy failure in falciparum malaria in Cambodia. Malar. J. 2009;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M., Ferreira P.E., Tarning J., Ursing J., Ngasala B., Björkman A., Mårtensson A., Gil J.P. Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance phenotype as assessed by patient antimalarial drug levels and its association with pfmdr1 polymorphisms. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;207:842–847. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M., Ngasala B., Ferreira P.E., Larsson E., Jovel I., Hjalmarsson A., Petzold M., Premji Z., Gil J.P., Björkman A., Mårtensson A. Temporal trends of molecular markers associated with artemether-lumefantrine tolerance/resistance in Bagamoyo district, Tanzania. Malar. J. 2013;12:103. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mang'era C.M., Mbai F.N., Omedo I.A., Mireji P.O., Omar S.A. Changes in genotypes of Plasmodium falciparum human malaria parasite following withdrawal of chloroquine in Tiwi, Kenya. Acta Trop. 2012;123:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhamad P., Phompradit P., Sornjai W., Maensathian T., Chaijaroenkul W., Rueangweerayut R., Na-Bangchang K. Polymorphisms of molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistance and relationship with artesunate mefloquine combination therapy in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;85:568–572. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwai L., Kiara S.M., Abdirahman A., Pole L., Rippert A., Diriye A., Bull P., Marsh K., Borrmann S., Nzila A. In vitro activities of piperaquine, lumefantrine, and dihydroartemisinin in Kenyan Plasmodium falciparum isolates and polymorphisms in pfcrt and pfmdr1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5069–5073. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00638-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na B.K., Karbwang J., Thomas C.G., Thanavibul A., Sukontason K., Ward S.A., Edwards G. Pharmacokinetics of artemether after oral administration to healthy Thai males and patients with acute, uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994;37:249–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngalah B.S., Ingasia L.A., Cheruiyot A.C., Chebon L.J., Juma D.W., Muiruri P., Onyango I., Ogony J., Yeda R.A., Cheruiyot J., Mbuba E., Mwangoka G., Achieng A.O., Ng'ang'a Z., Andagalu B., Akala H.M., Kamau E. Analysis of major genome loci underlying artemisinin resistance and pfmdr1 copy number in pre- and post-ACTs in western Kenya. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8308. doi: 10.1038/srep08308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noedl H., Se Y., Schechter K., Smith B.L., Socheat D., Fukuda M.M. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogutu B.R., Onyango K.O., Koskei N., Omondi E.K., Ongecha J.M., Otieno G.A., Obonyo C., Otieno L., Eyase F., Johnson J.D., Omollo R., Perkins D.J., Akhwale W., Juma E. Efficacy and safety of artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Kenyan children aged less than five years: results of an open-label, randomized, single-centre study. Malar. J. 2014;13:33. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okiro E., Alegana V., Noor A., Snow R. Changing malaria intervention coverage, transmission and hospitalization in Kenya. Malar. J. 2010;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okombo J., Kamau A.W., Marsh K., Sutherland C.J., Ochola-Oyier L.I. Temporal trends in prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance alleles over two decades of changing antimalarial policy in coastal Kenya. 2014;4(3):152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot S., Olliaro P., de Monbrison F., Bienvenu A.L., Price R.N., Ringwald P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence for correlation between molecular markers of parasite resistance and treatment outcome in falciparum malaria. Malar. J. 2009;8:89. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.N., Cassar C., Brockman A., Duraisingh M., van Vugt M., White N.J., Nosten F., Krishna S. The pfmdr1 gene is associated with a multidrugresistant phenotype in Plasmodium falciparum from the western border of Thailand. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2943–2949. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.N., Uhlemann A.C., Brockman A., McGready R., Ashley E., Phaipun L., Patel R., Laing K., Looareesuwan S., White N.J., Nosten F., Krishna S. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet. 2004;364:438–447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16767-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rason M.A., Randriantsoa T., Andrianantenaina H., Ratsimbasoa A., Menard D. Performance and reliability of the SYBR Green I based assay for the routine monitoring of susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008;102:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed M.B., Saliba K.J., Caruana S.R., Kirk K., Cowman A.F. Pgh1 modulates sensitivity and resistance to multiple antimalarials in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2000;403:906–909. doi: 10.1038/35002615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shretta R., Omumbo J., Rapuoda B., Snow R.W. Using evidence to change antimalarial drug policy in Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2000;5:755–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu A.B., Valderramos S.G., Fidock D.A. pfmdr1 mutations contribute to quinine resistance and enhance mefloquine and artemisinin sensitivity in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:913–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisowath C., Stromberg J., Mårtensson A., Msellem M., Obondo C., Björkman A., Gil J.P. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 86 N coding alleles by artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem) J. Infect. Dis. 2005;191:1014–1017. doi: 10.1086/427997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisowath C., Ferreira P.E., Bustamante L.Y., Dahlstrom S., Mårtensson A., Björkman A., Krishna S., Gil J.P. The role of pfmdr1 in Plasmodium falciparum tolerance to artemether-lumefantrine in Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2007;12:736–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisowath C., Petersen I., Veiga M.I., Mårtensson A., Premji Z., Björkman A., Fidock D.A., Gil J.P. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum parasites carrying the chloroquine-susceptible pfcrt K76 allele after treatment with artemether-lumefantrine in Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:750–757. doi: 10.1086/596738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Some A.F., Sere Y.Y., Dokomajilar C., Zongo I., Rouamba N., Greenhouse B., Ouedraogo J.B., Rosenthal P.J. Selection of known Plasmodium falciparum resistance-mediating polymorphisms by artemether-lumefantrine and amodiaquinesulfadoxine-pyrimethamine but not dihydroartemisininpiperaquine in Burkina Faso. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1949–1954. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01413-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska K., Ashley E., Lee S.J., Anstey N., Barnes K.I., Binh T.Q., D'Alessandro U., Day N.P., de Vries P.J., Dorsey G., Guthmann J.P., Mayxay M., Newton P.N., Olliaro P., Osorio L., Price R.N., Rowland M., Smithuis F., Taylor W.R., Nosten F., White N.J. In vivo parasitological measures of artemisinin susceptibility. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:570–579. doi: 10.1086/650301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S.M., Parobek C.M., DeConti D.K., Kayentao K., Coulibaly S.O., Greenwood B.M., Tagbor H., Williams J., Bojang K., Njie F., Desai M., Kariuki S., Gutman J., Mathanga D.P., Mårtensson A., Ngasala B., Conrad M.D., Rosenthal P.J., Tshefu A.K., Moormann A.M., Vulule J.M., Doumbo O.K., Ter Kuile F.O., Meshnick S.R., Bailey J.A., Juliano J.J. Absence of putative artemisinin resistance mutations among plasmodium falciparum in Sub-Saharan Africa: a molecular epidemiologic study. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;211:680–688. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W., Jensen J.B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlemann A.C., Ramharter M., Lell B., Kremsner P.G., Krishna S. Amplification of Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance Gene 1 in isolates from Gabon. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:1830–1835. doi: 10.1086/497337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan M., Gadalla N.B., Stepniewska K., Dahal P., Nsanzabana C., Moriera C., Price R.N., Mårtensson A., Rosenthal P.J., Dorsey G., Sutherland C.J., Guérin P., Davis T.M., Ménard D., Adam I., Ademowo G., Arze C., Baliraine F.N., Berens-Riha N., Björkman A., Borrmann S., Checchi F., Desai M., Dhorda M., Djimdé A.A., El-Sayed B.B., Eshetu T., Eyase F., Falade C., Faucher J.F., Fröberg G., Grivoyannis A., Hamour S., Houzé S., Johnson J., Kamugisha E., Kariuki S., Kiechel J.R., Kironde F., Kofoed P.E., LeBras J., Malmberg M., Mwai L., Ngasala B., Nosten F., Nsobya S.L., Nzila A., Oguike M., Otienoburu S.D., Ogutu B., Ouédraogo J.B., Piola P., Rombo L., Schramm B., Somé A.F., Thwing J., Ursing J., Wong R.P., Zeynudin A., Zongo I., Plowe C.V., Sibley C.H., ASAQ Molecular Marker Study Group; WWARN AL Polymorphisms in plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and multidrug resistance 1 genes: parasite risk factors that affect treatment outcomes for P. falciparum malaria after artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014;91:833–843. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinayak S., Alam M.T., Sem R., Shah N.K., Susanti A.I., Lim P., Muth S., Maguire J.D., Rogers W.O., Fandeur T., Barnwell J.W., Escalante A.A., Wongsrichanalai C., Ariey F., Meshnick S.R., Udhayakumar V. Multiple genetic backgrounds of the amplified Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance (pfmdr1) gene and selective sweep of 184F mutation in Cambodia. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:1551–1560. doi: 10.1086/651949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N.J. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): the price of success. Science. 2008;320(5874):330–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1155165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N.J., van V.M., Ezzet F. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of artemether-lumefantrine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:105–125. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- W.H.O . 2014. Status Report on Artemisinin Resistance.http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/status_rep_artemisinin_resistance_jan2014.pdf Available at: 371; 5. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2013. World Malaria Report.http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2013/report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Zwang J., Dorsey G., Mårtensson A., d'Alessandro U., Ndiaye J.L., Karema C., Djimde A., Brasseur P., Sirima S.B., Olliaro P. Plasmodium falciparum clearance in clinical studies of artesunate-amodiaquine and comparator treatments in sub-Saharan Africa, 1999-2009. Malar. J. 2014;13:114. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]