Abstract

Pulmonary extra-intestinal manifestations (EIM) of inflammatory bowel disease are well described with a variable incidence. We present a case of Crohn's disease with pulmonary EIM including chronic bronchitis with non-resolving bilateral cavitary pulmonary nodules and mediastinal lymphadenopathy successfully treated with infliximab. Additionally, we present a case summary from a literature review on pulmonary EIM successfully treated with infliximab. Current treatment recommendations include an inhaled and/or systemic corticosteroid regimen which is largely based on case reports and expert opinion. We offer infliximab as an adjunctive therapy or alternative to corticosteroids for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease related pulmonary EIM.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Pulmonary extraintestinal manifestations, Infliximab

List of abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; EIM, extra-intestinal manifestations; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, is a chronic inflammatory condition primarily associated with the gastrointestinal tract. These diseases have numerous extra-intestinal manifestations (EIM), such as pyoderma gangrenosum, episcleritis, uveitis, polyarticular arthritis, thromboembolic disease and a myriad of pulmonary abnormalities [1]. Pulmonary EIM are considered rare manifestations of IBD despite increasing evidence suggesting frequent pulmonary involvement [2–4]. Numerous case series and review articles have been published, describing a variety of pathologic and radiologic presentations [2,3].

Despite increasing awareness and knowledge about IBD associated pulmonary disease, little is known about its treatment. Current treatment recommendations are empirical and based upon expert opinion, with an emphasis on the use of inhaled or systemic corticosteroids [3,5]. Because of the low incidence and high variability in presentation, randomized controlled trials to evaluate treatment efficacy have not been performed.

Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, can be used for the treatment of moderate and severe IBD. Additionally, infliximab has also been shown to improve some EIM refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. Only a few cases of IBD associated pulmonary EIM treated with infliximab are found in the literature [6–11]. We present a case of Crohn's disease with pulmonary EIM treated with infliximab and a literature review.

2. Case report

A 33-year-old morbidly obese male, employed as a prison guard, presented with a six week history of cough. The patient subsequently developed fever, nausea, occasional emesis, non-bloody diarrhea and a 25-pound unintentional weight loss. A chest radiograph revealed a patchy nodular shaped density in the left lower lobe. The patient received two courses of antibiotics with resolution of the fever but persistence of the infiltrate on serial chest radiographs. Given the persistent infiltrate and abdominal symptoms, pulmonary and gastroenterology referrals were ordered.

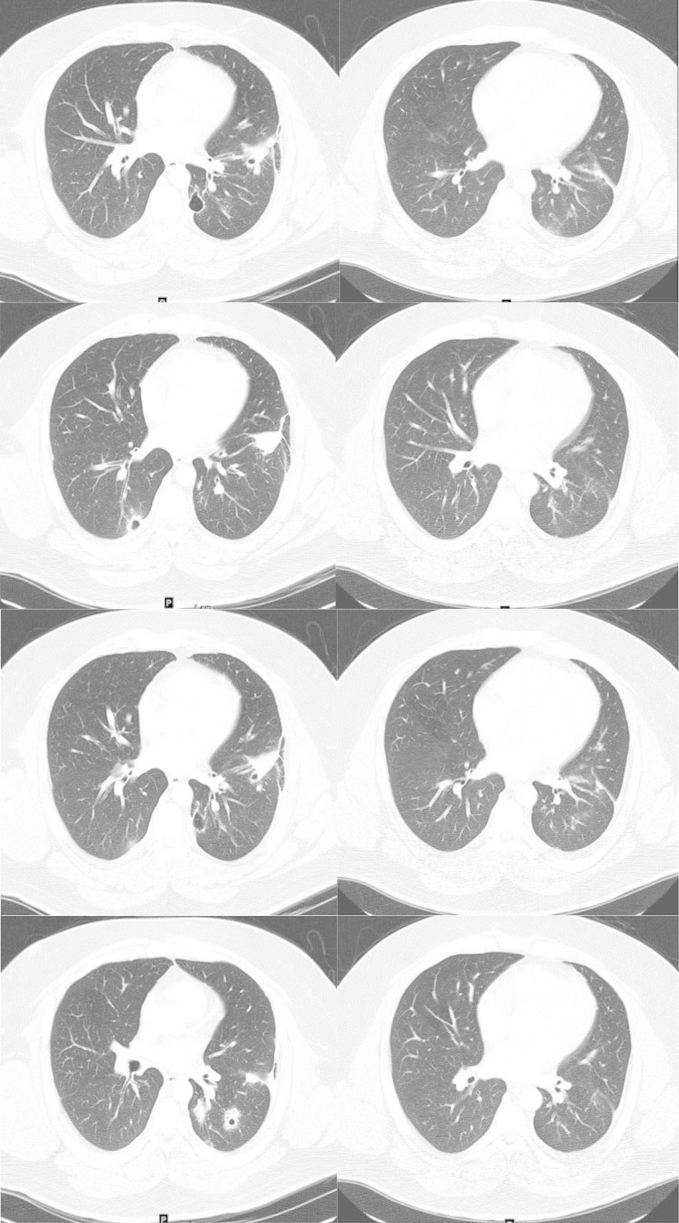

Chest, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography were obtained at the time of gastroenterology evaluation, revealing scattered bilateral cavitary pulmonary nodules with parenchymal airspace disease in the left lower lobe and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1 – left column). Additionally, mesenteric lymph node enlargement with inflammatory stranding and thickening of the terminal ileum was noted. Subsequent colonoscopy revealed colitis of the ascending colon with friable mucosa and skip lesions. Forcep biopsies within the ascending colon demonstrated marked chronic active colitis with crypt abscess formation and focal areas suspicious for granuloma, consistent with Crohn's disease.

Fig. 1.

Chest computed tomography before (left column) and after (right column) therapy.

Following pulmonary evaluation, flexible bronchoscopy revealed negative bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast cultures and benign pulmonary parenchyma with mild acute and chronic bronchitis with intra-alveolar macrophages. No evidence of malignancy was found. Serologic evaluation including, fungal serologies, HIV antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, urinary and serum histoplasma antigen, cryptococcus antibody, and galactomann aspergillus assay were all negative. T-spot and Mantoux screening test were negative as well.

After diagnostic evaluation, treatment consisted of prednisone and mesalamine, which improved his diarrhea although the lung disease persisted. After consulting with gastroenterology, the patient was started on infliximab and responded both clinically with the resolution of his cough and radiographically with marked decrease in the size of the cavitary lung lesions and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1 – right column). The time period between pre and post computed tomography evaluation as shown in Fig. 1 was approximately 6.5 months with an interval evaluation revealing stability of findings prior to infliximab administration. The follow-up imaging was performed approximately 2 months after treatment with infliximab.

3. Discussion

The prevalence of IBD is 396/100,000 which is approximately 1.4 million Americans [12]. In general, extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD have been reported in anywhere from 6 to 47% of cases [1]. When pulmonary EIM have been specifically studied the prevalence has been highly variable, depending on the diagnostic criteria and clinical or subclinical nature. Most studies reveal pulmonary manifestations in 30–60% of patients [2,3], while some studies have revealed a much lower incidence (<1%) [4]. Despite some studies having a low incidence, the general consensus would advocate that pulmonary EIM are grossly under recognized. With this in mind, studies have identified pulmonary EIM through symptoms (44–50%), imaging (25–50%), pulmonary function test (42%), bronchoalveolar lavage (50%), and through population studies identifying an increase incidence of VTE and asthma [2]. Pulmonary function tests have not been found to be overly useful or reliable in the setting of pulmonary EIM identification. Multiple reports have demonstrated a decreased diffusion capacity and other reports have variably shown airflow obstruction, small airway dysfunction, increased functional residual capacity, hyperinflation and bronchial reactivity to methacholine challenge [2]. The most common interstitial and airway pulmonary EIM have been found to be bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia and bronchiectasis respectively [3,13].

Literature review reveals primarily expert opinion regarding therapy. The diagnosis and directed therapy for pulmonary IBD EIM is reserved for patients with symptoms and abnormal imaging that is unaccounted for after an extensive workup including infectious, autoimmune and pathologic evaluation. Spontaneous resolution has been described and delay in diagnostic evaluation could lead to a failed diagnosis. Corticosteroids have been the mainstay of treatment used in about 2/3 of cases; however, up to 1/3 of patients fail treatment either because they do not respond or cannot be tapered off corticosteroids [2,3]. It is important to note that corticosteroid failure is less common in upper airway involvement, interstitial lung disease, cavitary pulmonary nodules and serositis [3,5]. A graded mixture of inhaled and oral corticosteroids at high doses has been recommended based on the nature of pulmonary involvement [3]. With such a rare problem, RCT are unlikely and case reports with expert opinion often lags behind new treatment modalities.

Infliximab therapy has been shown to be efficacious in other EIM's that have generally failed conventional immunosuppressive therapy. They have been specifically shown to be effective in IBD EIM such as spondylarthropathies, refractory erythroderma nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, sweets syndrome and uveitis [14]. Interestingly, patients with pulmonary EIM have been concurrently seen to have other EIMs such as pyoderma gangrenosum and spondylarthropathies [15]. When the use of infliximab for pulmonary EIM was reviewed, only eight cases (Table 1) were discovered [6–11]. Most were case reports or brief case series in patients with Crohn's disease. Two cases, including our own, had pulmonary EIM diagnosed before or at the time that the IBD was diagnosed. All patients received extensive evaluation including tissue sampling to assist in diagnosis. In these cases, infliximab was the only anti-TNF that was used as either adjunctive or monotherapy. All cases resulted in clinical and radiographic resolution of the pulmonary IBD EIM.

Table 1.

Literature review of infliximab therapy for pulmonary extra-intestinal manifestations.

| Age (yrs) | Sex | Duration (yrs)* | Type | Radiographic findings | Pathology | PSE | MES | 6-MP | AZI | INF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alrashid [6] | 66 | F | 3 | Crohn's | Pulmonary nodules | BOOP, NCG | X | ● | |||

| Gill [7] | 20 | F | 9 | Pulmonary nodules Liver nodules |

NCG | X | ● | ||||

| Krishnan [9] | 13 | F | 4 | Pleural and intraparenchymal infiltrates without lymphadenopathy | NCG | X | X● | ● | |||

| 14 | F | 3 | Scattered granulomatous lesions without lymphadenopathy | NCG | X | X● | ● | ||||

| 17 | M | 4 | Bilateral basal infiltrates and effusions | BOOP | ● | X | X | ● | |||

| Kirkcaldy [8] | 41 | F | −2 | Concentric soft-tissue thickening Glottis to intrathoracic trachea |

NCG | X | ● | ||||

| Silbermintz [11] | 13 | F | 3 | Multilobar consolidation Pleural and intraparenchymal infiltrate |

NCG | X | X | ● | |||

| Pedersen [10] | 35 | F | 11 | Pulmonary nodules, Parenchymal infiltrates, Pleural effusions | NCG | X | X | ● | |||

| Case Report | 33 | M | 0 | Cavitary pulmonary nodules Parenchymal airspace disease Mediastinal lymphadenopathy |

Bronchitis Intra-alveolar macrophages |

X● | X● | ● |

PSE – Prednisone, MES – Mesalamine, 6-MP – 6-mercaptopurine, AZI – Azithioprine, INF – Infliximab, NCG – Noncaseating Granulomas, BOOP – Bronchiolitis Obliterans with Organizing Pneumonia, X – Incoming maintenance therapy, ● – Discharge therapy, * – Duration from IBD to EIM presentation.

4. Conclusion

We present a case of Crohn's disease with pulmonary EIM successfully treated with infliximab. With review of the literature demonstrating possible efficacy, we would advocate infliximab as an adjunctive or alternative therapy to corticosteroids in pulmonary EIM of IBD until appropriate randomized controlled trials can be performed. If infliximab is considered as an alternative therapy, diligence must be used to exclude infectious etiologies, particularly mycobacterial and fungal disease given probable previous history of immunosuppressant use and the risks associated with infliximab administration.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Hayek has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr. Pfanner has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr. White has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures

No financial support was provided for this paper.

Author contributions

Dr Hayek – contributed to manuscript writing and editing.

Dr Pfanner – contributed to manuscript writing and editing.

Dr White – contributed to manuscript writing and editing.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

These findings have been presented as a poster presentation at Chest in Austin, Texas in October 2014.

Contributor Information

Adam J. Hayek, Email: ahayek@sw.org.

Timothy P. Pfanner, Email: tpfanner@sw.org.

Heath D. White, Email: hdwhite@sw.org.

References

- 1.Bernstein C.N., Wajda A., Blanchard J.F. The clustering of other chronic inflammatory diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:827–836. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black H., Mendoza M., Murin S. Thoracic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Chest. 2007;131:524–532. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camus P., Colby T.V. The lung in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. Respir. 2000;15:5–10. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15100500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers B.H., Clark L.M., Kirsner J.B. The epidemiologic and demographic characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease: an analysis of a computerized file of 1400 patients. J. Chronic Dis. 1971;24:743–773. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(71)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spira A., Grossman R., Balter M. Large airway disease associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Chest. 1998;113:1723–1726. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alrashid A.I., Brown R.D., Mihalov M.L., Sekosan M., Pastika B.J., Venu R.P. Crohn's disease involving the lung: resolution with infliximab. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001;46:1736–1739. doi: 10.1023/a:1010665807294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill K.R.S., Mahadevan U. Infliximab for the treatment of metastatic hepatic and pulmonary Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005;11:210–212. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkcaldy J., Lim W.S., Jones A., Pointon K. Stridor in Crohn disease and the use of infliximab. Chest. 2006;130:579–581. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan S., Banquet A., Newman L., Katta U., Patil A., Dozor A.J. Lung lesions in children with Crohn's disease presenting as nonresolving pneumonias and response to infliximab therapy. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1440–1443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen N., Duricova D., Munkholm P. Pulmonary Crohn's disease: a rare extra-intestinal manifestation treated with infliximab. J. Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silbermintz A., Krishnan S., Banquet A., Markowitz J. Granulomatous pneumonitis, sclerosing cholangitis, and pancreatitis in a child with Crohn disease: response to infliximab. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2006;42:324–326. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189347.32796.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakatos P.L. Recent trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: up or down? World. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6102–6108. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonniere P., Wallaert B., Cortot A. Latent pulmonary involvement in Crohn's disease: biological, functional, bronchoalveolar lavage and scintigraphic studies. Gut. 1986;27:919–925. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.8.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutgeerts P., Van Assche G., Vermeire S. Review article: infliximab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease–seven years on. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;23:451–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen S., Bendtzen K., Nielsen O.H. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Ann. Med. 2010;42:97–114. doi: 10.3109/07853890903559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]