Abstract

Objective:

We conducted an expedited knowledge synthesis (EKS) to facilitate evidence-informed decision making concerning youth suicide prevention, specifically school-based strategies and nonschool-based interventions designed to prevent repeat attempts.

Methods:

Systematic review of review methods were applied. Inclusion criteria were as follows: systematic review or meta-analysis; prevention in youth 0 to 24 years; peer-reviewed English literature. Review quality was determined with AMSTAR (a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews). Nominal group methods quantified consensus on recommendations derived from the findings.

Results:

No included review addressing school-based prevention (n = 7) reported decreased suicide death rates based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled cohort studies (CCSs), but reduced suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, and proxy measures of suicide risk were reported (based on RCTs and CCSs). Included reviews addressing prevention of repeat suicide attempts (n = 14) found the following: emergency department transition programs may reduce suicide deaths, hospitalizations, and treatment nonadherence (based on RCTs and CCSs); training primary care providers in depression treatment may reduce repeated attempts (based on one RCT); antidepressants may increase short-term suicide risk in some patients (based on RCTs and meta-analyses); this increase is offset by overall population-based reductions in suicide associated with antidepressant treatment of youth depression (based on observational studies); and prevention with psychosocial interventions requires further evaluation. No review addressed sex or gender differences systematically, Aboriginal youth as a special population, harm, or cost-effectiveness. Consensus on 6 recommendations ranged from 73% to 100%.

Conclusions:

Our EKS facilitates decision maker access to what is known about effective youth suicide prevention interventions. A national research-to-practice network that links researchers and decision makers is recommended to implement and evaluate promising interventions; to eliminate the use of ineffective or harmful interventions; and to clarify prevention intervention effects on death by suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Such a network could position Canada as a leader in youth suicide prevention.

Keywords: suicide, prevention, youth, mental health, systematic review

Abstract

Objectif :

Nous avons mené une synthèse accélérée des connaissances (SAC) pour faciliter le processus décisionnel éclairé par des données probantes concernant la prévention du suicide chez les jeunes, plus particulièrement les stratégies en milieu scolaire et les interventions en milieu non scolaire destinées à prévenir les tentatives répétées.

Méthodes :

Une revue systématique des méthodes des revues a été effectuée. Les critères d’inclusion étaient les suivants : une revue systématique ou méta-analyse; la prévention chez les jeunes de 0 à 24 ans; la littérature en anglais révisée par les pairs. La qualité des revues était déterminée par AMSTAR (un outil de mesure pour évaluer les revues systématiques). Les méthodes du groupe nominal quantifiaient le consensus des recommandations tirées des résultats.

Résultats :

Aucune revue incluse qui traitait de la prévention en milieu scolaire (n = 7) ne rapportait de taux réduits de décès par suicide d’après des essais randomisés contrôlés (ERC) ou des études de cohortes contrôlées (ECC), mais des tentatives de suicide réduites, l’idéation suicidaire, et des mesures substitutives du risque de suicide ont été rapportées (selon les ERC et ECC). Les revues incluses sur la prévention des tentatives de suicide répétées (n = 14) ont constaté que : les programmes de transition des services d’urgence peuvent réduire les décès par suicide, les hospitalisations, et la non-observance du traitement (selon les ERC et ECC); la formation en traitement de la dépression des prestataires de soins de première ligne peut réduire les tentatives répétées (selon un ERC); les antidépresseurs peuvent augmenter le risque de suicide à court terme chez certains patients (selon les ERC et méta-analyses); cette augmentation est compensée par des réductions globales du suicide dans la population associées au traitement par antidépresseur de la dépression chez les jeunes (selon des études par observation); et la prévention avec interventions psychosociales exige plus d’évaluation. Aucune revue n’a traité systématiquement des différences selon le sexe, des jeunes autochtones en tant que population spéciale, des dommages, ou de coût efficacité. Pour 6 recommandations, le consensus s’échelonnait de 73 % à 100 %.

Conclusions :

Notre SAC facilite l’accès aux décideurs pour des interventions efficaces connues de prévention du suicide chez les jeunes. Un réseau national de recherche à la pratique qui relie chercheurs et décideurs est recommandé pour mettre en oeuvre et évaluer les interventions prometteuses, éliminer l’usage des interventions inefficaces ou nuisibles, et clarifier les effets des interventions préventives sur les décès par suicide, les tentatives de suicide, et l’idéation suicidaire. Ce réseau pourrait faire du Canada un chef de file de la prévention du suicide ches les jeunes.

Suicide-related behaviours in children and youth are a global public health problem.1 In Canada, death by suicide is the second leading cause of mortality among 15-to 24-year-olds (about 10.8 deaths per 100 000 in 2011).2 As many as 8% of youth are thought to attempt suicide, annually, and one-third of all attempts (that is, about 2.5% of youth) are considered medically serious.3 Suicidal ideation in the last 12 months, a predictor of suicide attempts,4 is reported by about 15% of youth.3 Even though about 50% of youth who die by suicide are seen by a primary care provider in the 6 months prior to death, well-documented modifiable risk factors for SRB, namely, untreated or inadequately treated mental health problems (particularly depression and substance abuse), are present at death in as many as 90% of these youth.5 In Canada, SRB cost $2.4 billion in 2004, including $707 million in direct costs (that is, health care services) and $1.7 billion in indirect costs (that is, societal costs of lost productivity).6

The need for strengthened policies and programs to prevent SRB and reduce the associated high cost and burden of suffering has received increased attention in Canada. Specifically, the recent passage of Bill C-300 (An Act Respecting a Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention in Canada)7 calls for evidence-informed guidelines that identify when, where, and how to intervene to reduce suicide risk across the life-course, and a mechanism to make them available to regional, provincial, and federal decision makers. The goal is to break down barriers that limit decision maker access to and use of research about effective prevention interventions. Within this context, we report the findings of an EKS conducted to derive evidence-informed recommendations regarding effective SRB prevention interventions relevant to Canadians aged 24 years and younger. This work was carried out within the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Evidence on Tap program, which aims to facilitate the use of rigorous research knowledge by linking researchers with decision makers to address their specific knowledge needs. Two synthesis questions relevant to the implementation of Bill C-300 are addressed7:

What universal and targeted school-based interventions are effective in preventing death by suicide, attempted suicide, and (or) suicidal ideation in youth aged 0 to 24 years? Schools provide a convenient way to reach large numbers of youth, using both universal and targeted interventions, and by targeting a wide range of modifiable risk factors.

What is known about the effectiveness of interventions to prevent death by suicide, attempted suicide, and (or) suicidal ideation in youth aged 0 to 24 years who have made one or more suicide attempts? A previous suicide attempt is thought to be one of the most potent predictors of youth suicide.8 Among youth who attempt suicide and present to a hospital setting, the risk of death due to a subsequent suicide attempt is about 10 times that of the rates observed among their peers.9

For each question, we also sought to synthesize what is known about sex and (or) gender differences in intervention effects10 and effectiveness in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit youth.

Methods

No established method for conducting an EKS currently exists.11 We carried out a systematic review of reviews to enable completion within the 6-month Evidence on Tap time frame. Our protocol is unregistered because this review method was not eligible for inclusion in the PROSPERO database at project start-up.12

An international EAG composed of youth suicide researchers, knowledge synthesis and translation experts, mental health service providers, and knowledge users representing national initiatives and provincial government decision makers was formed. The core research team (Dr Bennett and Stephanie Duda) brought decision points regarding methodology, summary of findings, and interpretation to the EAG at regular intervals, using an iterative, consultative approach.13,14

Clinical Implications

Interventions that increase contact between youth and trained professionals show promise in preventing youth suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

School-based interventions may reduce suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

Interventions to prevent repeat suicide attempts show promise for youth who seek care, but little is known about how to reduce attempts among youth who do not seek care.

Limitations

Very few RCTs of youth suicide prevention programs exist.

Little data exist regarding the impact of youth suicide prevention programs on death by suicide.

Both the benefits and harms of interventions need to be evaluated before widespread use.

Little or no evidence exists regarding sex and (or) gender differences in intervention effectiveness or suicide prevention in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis youth.

Our approach was derived from Cochrane methods15 and conforms to PRISMA reporting standards.16

Literature Search

A research librarian (Maureen Rice) searched the following databases from January 1980 to May 2012 to identify reviews of youth suicide prevention interventions: MEDLINE (including HealthSTAR), PsycINFO (including Dissertation Abstracts International), Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library and Child Health Field Register, the Campbell Collaboration SPECTR database, Canadian Electronic Library, Proceedings First, Social Science Abstracts, and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (commonly referred to as ASSIA). The search strategy was developed for MEDLINE and adapted for the other databases as required. The MEDLINE 6-step search strategy was as follows: exp Suicide/pc [Prevention & Control]; (suicide adj prevent*). tw; 1 or 2; limit 3 to English language; limit 4 to “review”; limit 5 to yr=“1980–Current.” Strategies for other databases are available from the correspondence author.

The 3 review inclusion criteria comprised the following: systematic review or meta-analysis; suicide prevention interventions in youth aged 0 to 24 years; and peer-reviewed, English-language publication.

Two reviewers completed these tasks independently in duplicate following training. Disagreements were resolved through consultation with the principal investigator (Dr Bennett). Eligible reviews were quality-assessed using AMSTAR (a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews).17 Quality scores were based on the 5 AMSTAR items that align with Cochrane risk of bias criteria: a priori design provided; comprehensive literature search; included and excluded studies provided; characteristics of included studies provided; and appropriate use of scientific quality in formulating conclusions. Data from reviews that obtained a quality score of 3 or more out of 5 were abstracted using a standardized form.

EAG members were asked to nominate primary studies published after included reviews, as a comprehensive search of primary studies was not feasible in the 6-month Evidence on Tap time frame. Inclusion criteria comprised the following: RCT or CCS; suicide prevention intervention in youth 0 to 24 years of age; and peer-reviewed, English-language publication. Cochrane risk of bias criteria were selected to assess primary study quality.18

Interventions were organized using 7 categories derived from Mann et al19: education and awareness for the general public and professionals; screening tools for at-risk people; treatment of psychiatric disorder; treatment of SRB; restricting access to lethal means; responsible media reporting; and other (to accommodate any additional intervention types).

Evidence of intervention effectiveness was sought in the following 2 areas: reductions in death by suicide, suicide attempt, and suicidal ideation; and proxy measures of reduced suicide risk, which included the following 4 aspects: increased suicide awareness (knowledge and attitudes); decreased risk factors (for example, hopelessness, depression, suicide risk score, and loneliness); increased protective factors (for example, coping skills, problem solving skills, resiliency, empathy, and self-efficacy); and increased access to health services (for example, increased help seeking behaviour, referral rates, and entry into treatment).

Nominal group methods were used to quantify EAG consensus on 6 recommendations derived from the EKS findings.20 First, members (n = 15) indicated their level of agreement with a set of draft recommendations, using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Ratings were collected anonymously using an online survey. EAG members were then provided with a collated summary of the scores and participated in a conference call to discuss and revise each recommendation as necessary. Finally, EAG members re-rated their agreement with each revised recommendation in a second anonymous online exercise.

Results

Search and Screening

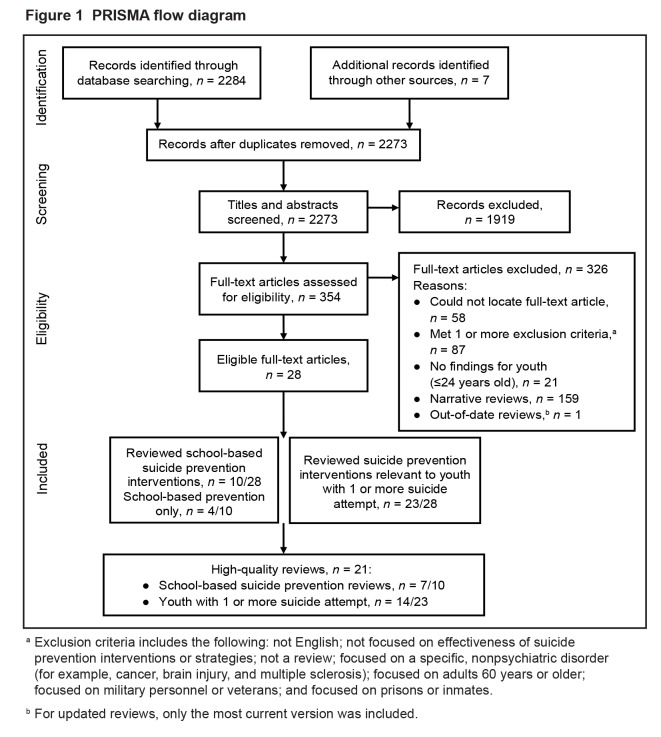

Twenty-eight reviews were deemed eligible as shown in Figure 1.16 Ten included primary studies of school-based prevention (4 of 10 focused solely on school-based interventions). Twenty-three of the 28 reviews reported on interventions that were nonschool-based and relevant to youth who have attempted suicide at least once. Two primary studies were nominated, but both were included in 1 or more reviews.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

aExclusion criteria includes the following: not English; not focused on effectiveness of suicide prevention interventions or strategies; not a review; focused on a specific, nonpsychiatric disorder (for example, cancer, brain injury, and multiple sclerosis); focused on adults 60 years or older; focused on military personnel or veterans; and focused on prisons or inmates.

b For updated reviews, only the most current version was included.

Eligible Review Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of included suicide prevention reviews

| Study (year) | AMSTAR RoB score | Total included studies, n | Relevant youth studies, n | Relevant youth studies in Canadian sample, n | Years searched | Study design inclusion criteria | Intervention categories reviewed

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Screening | Treatment

|

Access to means | Media | ||||||||||||

|

|

Psychiatric disorder | SRB | ||||||||||||||

| RCT | CC | NCC and (or) Other | SR and (or) MA | Public | Pros | |||||||||||

| Reviews relevant to school-based prevention | ||||||||||||||||

| Ploeg et al (1996)21 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 1980–1995 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Miller et al (2009)23 | 4 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 1967–2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Katz et al (2013)26 | 4 | 27 | 27 | 0 | 1960–2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Cusimano and Sameem (2011)25 | 3.5 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 1966–2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Mann et al (2005)19 | 3 | 93 | 6 | 2 | 1966–2005 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Isaac et al (2009)30 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 1806–NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Takada and Shima (2010) 24 | 3 | 34 | 14 | 1 | 1967–2007 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Breton et al (2002) 55 | 2 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 1970–1996 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Fountoulakis et al (2011)56 | 2 | 48 | 11 | 0 | NR–2010 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Peña and Caine (2006)57 | 1 | 17 | 9 | 0 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Reviews relevant to youth with ≥1 suicide attempt | ||||||||||||||||

| Newton et al (2010)33 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1985–2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Hawton et al (2009)41 | 5 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 1966–1999 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Crawford et al (2007)42 | 5 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 1966–2005 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ougrin et al (2012)38 | 5 | 14 | 14 | 0 | NR–2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Tarrier et al (2008)37 | 5 | 28 | 6 | 1 | 1980–NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Robinson et al (2011)39 | 4 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 1980–2010 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Corcoran et al (2011)43 | 4 | 17 | 17 | 2 | NR–2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Hahn et al (2005)48 | 4 | NR | 2 | 0 | 1979–2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Daigle et al (2011)44 | 4 | 35 | 4 | 0 | 1966–2010 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Burns et al (2005)45 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 1 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Isaac et al (2009)30 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 1806–NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Hall and Lucke (2006)36 | 3 | 25 | 6 | 0 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Mann et al (2005)19 | 3 | 93 | 11 | 2 | 1966–2005 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hepp et al (2004)46 | 3 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 1996–2003 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Durkee et al (2011)58 | 2 | NR | 1 | NR | NR | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Fountoulakis et al (2011)56 | 2 | 48 | 4 | NR | NR–2010 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Breton et al (2002)55 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 1970–1996 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Links and Hoffman (2005) 59 | 2 | 34 | 3 | NR | 1994–2004 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Macgowan (2004)60 | 2 | 10 | 10 | NR | NR–2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Peña and Caine (2006)57 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 0 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| McMyler and Pryjamchuk (2008)61 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sakinofsky (2007)62 | 1 | NR | 5 | NR | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Möller (2006)63 | 1 | NR | 1 | 0 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

AMSTAR = a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews; CC = controlled cohort; MA = meta-analysis; NCC = noncontrolled cohort; NR = not reported; Pros = professionals; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RoB = risk of bias; SR = systematic review; SRB = suicide-related behaviour

Seven of 10 reviews were judged of high quality (AMSTAR score ≥3/5). Among them, the number of included primary studies varied from 3 to 27, with 22 unique primary studies. Overlap of included studies between reviews was low to moderate. The number of primary studies conducted in Canadian populations ranged from 0 to 2. Education of the public (suicide awareness curricula, skills training, and gatekeeper training) and professionals (gatekeeper training and postvention), and screening for suicide risk were addressed in 1 or more of the 7 reviews. Eligible reviews focused exclusively on studies of prevention in elementary and secondary school, with the exception of one review21 that included one primary study conducted in junior college students.22

Fourteen of 23 relevant reviews received an AMSTAR score of 3 or more out of 5. Among them, the total number of primary studies relevant to youth ranged from 2 to 17; the number of primary studies conducted in Canadian populations ranged from 0 to 2. Twelve reviews focused on pharmacologic or psychosocial treatment of psychiatric disorder or SRB, 2 addressed education of the public and professionals, and 1 addressed means restriction.

Findings: School-based Prevention (Table 2)

Table 2.

Summary of findings—school-based prevention

| Study (year) | ↓SRBs | Knowledge and (or) attitudes | Risk factorsa | Protective factorsb | Help seeking | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| D | A | I | ↑ | ↓ | NC | ↓ | ↑ | NC | ↑ | ↓ | NC | ↑ | ↓ | NC | |

| Education of the public | |||||||||||||||

| Suicide awareness curricula | |||||||||||||||

| Ploeg et al (1996)21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Mann et al (2005)19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Miller et al (2009)23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Takada and Shima (2010)24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Cusimano and Sameem (2011)25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Katz et al (2013)26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Skills training | |||||||||||||||

| Miller et al (2009)23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Katz et al (2013)26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Education of professionals | |||||||||||||||

| Gatekeeper training | |||||||||||||||

| Isaac et al (2009)30 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Katz et al (2013)26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Postvention | |||||||||||||||

| Ploeg et al (1996)21 | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Miller et al (2009)23 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Screening (with and without suicide awareness curricula) | |||||||||||||||

| Miller et al (2009)23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Takada and Shima (2010)24 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Cusimano and Sameem (2011)25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Katz et al (2013)26 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

A = attempt; D = death; I = ideation; NC = no change; SRB = suicide-related behaviour

Includes hopelessness, depression, suicide risk, and loneliness

Includes coping skills, problem solving, resiliency, empathy, and self-efficacy

Six reviews reported on curricula.19,21,23–26 Reductions in death by suicide were reported in 2 reviews23,24 derived from uncontrolled studies of low quality. Reductions in suicide attempts based on youth self-report were noted in 4 reviews,19,23,25,26 in each case derived from a single RCT (Signs of Suicide).27,28 Improvements in knowledge and attitudes were reported in all 6 reviews. Three reviews reported reductions in risk factors,21,23,24 with 2 reviews also noting studies where no change in risk factors was observed.21,23 Four reviews noted improvements in protective factors,19,21,23,24 but one also reported primary studies where no change occurred.23 Two of 6 reviews reported increased help seeking,23,25 while one reported no change.26

Two reviews addressed skills training.23,26 One26 reported reductions in suicidal ideation and attempts based on 1 RCT (Good Behaviour Game).29 Both reviews reported improvements in knowledge and attitudes, but 1 review23 also noted at least 1 primary study showing no change. Both reviews cited studies showing mixed effects (improvements and no change) in risk and protective factors and increased help seeking behaviour.

Two reviews26,30 noted increased knowledge and attitudes, and increased protective factors for gatekeeper training based on 1 RCT (Sources of Strength).31 Both reviews reported that the impact of gatekeeper training on death by suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation was not known.

One review23 found reductions in death by suicide and suicide attempts based on one uncontrolled study of low quality. The other review21 reported no change in risk factors associated with postvention based on an uncontrolled study of low quality.

Three reviews23–25 reported reductions in suicide attempts for screening combined with a suicide awareness curriculum based on one RCT (Signs of Suicide).27,28 A fourth review26 addressed screening alone, and concluded screening was not associated with harm due to labelling, based on one RCT (TeenScreen).32 All 4 reviews noted improved knowledge and skills. One review reported screening decreased risk factors and increased protective factors.23 Finally, 1 of 4 reviews reported increased help seeking,26 while 2 reported no change.23,25

None of the 7 reviews distinguished between universal and targeted intervention strategies in their findings. Further analysis of the included primary studies showed that the 7 reviews evaluated 26 universal and 5 targeted programs. Nineteen of the 26 universal programs included suicide awareness curricula; 17 of 26 included at least 1 other intervention component. Three of 5 targeted programs included skills training; awareness curricula were included in 2. Gatekeeper training was not included in any.

No review presented systematically derived findings comparing intervention impact in males and females.

No eligible review addressed Aboriginal youth as a special population.

Findings: Prevention in Youth Who Have Attempted Suicide (Table 3)

Table 3.

Summary of findings—prevention of repeat suicide attempts in youth

| Study (year) | ↓SRBs | Proxy outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| D | A | I | ↓ | ↑ | No effect | |

| Theme 1 Youth who seek care | ||||||

| Education of health professionals | ||||||

| Emergency department responses | ||||||

| Newton et al (2010)33 | ✓ | Suicide-related hospitalizations | Treatment adherence | Self-harm | ||

| Primary health care providers | ||||||

| Mann et al (2005)19 | ✓ | Identification of suicidal patients | ||||

| Treatment of psychiatric disorder | ||||||

| Pharmacological interventions | ||||||

| Hall et al (2006)36 | ✓ | |||||

| Mann et al (2005)19 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Psychosocial interventions | ||||||

| Tarrier et al (2008)37 | ||||||

| Ougrin et al (2012)38 | ||||||

| Robinson et al (2011)39 | ✓ | ✓ | Self-harm | Self-harm | ||

| Treatment of SRBs | ||||||

| Psychosocial interventions | ||||||

| Hawton et al (2009)41 | Self-harm | |||||

| Tarrier et al (2008)37 | ||||||

| Ougrin et al (2012)38 | Suicidal or nonsuicidal self-harm episodes | |||||

| Crawford et al (2007)42 | Rates of all-cause mortality | |||||

| Corcoran et al (2011)43 | ✓ | |||||

| Daigle et al (2011)44 | Self-harm | Self-harm | ||||

| Robinson et al (2011)39 | ✓ | Self-harm | Self-harm | |||

| Burns et al (2005)45 | Self-harm; missed appointments | Self-harm; missed appointments | ||||

| Hepp et al (2004)46 | Self-harm | |||||

| Theme 2 Youth who do not seek care | ||||||

| Education of public and professionals | ||||||

| Gatekeeper training | ||||||

| Isaac et al (2009)30 | Gatekeeper knowledge and skills | |||||

| Postvention | ||||||

| No reviews | ||||||

| Screening | ||||||

| No reviews | ||||||

| Treatment of psychiatric disorder | ||||||

| No reviews | ||||||

| Treatment of SRBs | ||||||

| No reviews | ||||||

| Means restriction | ||||||

| Hahn et al (2005)48 | ✓ | |||||

| Responsible media reporting | ||||||

| No reviews | ||||||

The 14 high-quality reviews relevant to preventing repeat SRB addressed 2 themes: strengthened health and social system responses to prevent repeat SRB in youth who seek care (n = 12 reviews); and (or) strategies to prevent repeat SRB in youth who do not seek care (n = 3). Findings for interventions relevant to each theme are presented below.

Two of the 12 reviews addressed this intervention strategy.19,33 One concluded, based on RCTs and CCS, that ED interventions combined with postdischarge follow-up reduced death by suicide, SRB hospitalizations, and treatment adherence.33 The second review19 reported that training primary care clinicians to treat depression reduced suicide attempts by more than 50%, compared with 18% in the control group (difference not statistically significant in one underpowered RCT)34; and that training primary care physicians to recognize psychological distress and suicidal ideation increased the identification of suicidal youth by 130% in a single pre–post study.35

Two of the 12 reviews addressed the effect of medication treatment for psychiatric disorder on SRB prevention in youth.19,36 One36 concluded based on 2 meta-analyses and 4 observational studies that: antidepressants may increase short-term suicide risk in some adolescents; and that this increase is balanced by overall population-based reductions in SRBs associated with drug treatment of adolescent depression. The second review19 drew similar conclusions. Three reviews37–39 addressed the impact of treatment of psychiatric disorder with psychosocial interventions on SRB. Tarrier et al37 concluded, based on RCTs and CCSs in youth and adults, that CBT interventions do not prevent repeat SRB when focused on symptoms such as depression or distress. The second review39 reported promising results for dialectical behaviour therapy based on one RCT. Specifically, suicidal ideation and attempts were reduced in youth presenting to a clinical service with a psychiatric diagnosis.40 The third review38 drew similar conclusions.

Nine reviews37–39,41–46 examined the treatment efficacy of psychosocial interventions for SRB. One39 reported that CBT reduced suicidal ideation in adolescents based on a single RCT.47 Another review43 found psychosocial interventions decreased suicidal events and self-harm (composite outcome) at posttest, but not at follow-up, based on RCTs and CCSs. All 9 reviews conclude that the role of psychosocial interventions in SRB prevention requires further evaluation. No reviews of medication treatment for SRB were found.

Gatekeeper training and postvention are relevant to increasing help seeking in youth at risk for repeat SRB who do not seek care. One review30 reported that gatekeeper training increased gatekeeper trainee knowledge and skills based on one RCT (Sources of Strength), but impact on help seeking behaviour, death by suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation was not assessed in this trial. No review reported whether postvention increases help seeking behaviour.

One review48 reported reductions in death by suicide based on 2 ecological studies49,50 of safe-storage gun laws. However, the decrease in death by firearm suicides was small and not statistically significant.49,50 Impact on other SRB was not addressed.

No review reported on these interventions in youth who do not seek care.

Again, conclusions regarding sex and (or) gender differences in intervention effects were not possible. One review44 noted that females were overrepresented in studies that reported the proportion of males and females, and that differences in outcome were almost never reported.

Again, no reviews addressed Aboriginal populations, specifically.

Recommendations and Consensus Results (Table 4)

Table 4.

Recommendations

|

CCS = controlled cohort study; ED = emergency department; EKS = expedited knowledge synthesis; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SRB = suicide-related behaviour

Table 4 presents 6 recommendations derived from the findings. All EAG members (n = 15) rated their agreement with each recommendation in the consensus exercise: 100% of members strongly agreed or agreed with the final versions of recommendations 2, 5, and 6; 93.3% of members strongly agreed or agreed with recommendation 4; 80% strongly agreed or agreed with recommendation 3 (1 member disagreed somewhat and 1 strongly disagreed); 73% strongly agreed or agreed with recommendation 1 (1 member strongly disagreed).

Discussion

We conducted an EKS that included consensus-derived recommendations to facilitate the use of research knowledge by decision makers responsible for the implementation of effective youth suicide prevention policies and programs. Twenty-one high-quality reviews were identified—7 relevant to school-based interventions and 14 relevant to the prevention of repeat suicide attempts. Findings are summarized by intervention type, SRB outcomes reported, and the availability of evidence from RCTs. The review of reviews methodology complements one other systematic review, which addresses prevention in all age groups19 by providing a comprehensive, up-to-date analysis of youth relevant suicide prevention intervention literature.

The provision of consensus-based recommendations addresses the recognized value added when expert groups such as ours provide guidance to decision makers that goes beyond a detailed synthesis of available evidence and its quality. For example, decision makers working in real time often have limited time and resources. Consequently, their ability to conduct a thorough evaluation of decision-relevant evidence and associated trade-offs is limited, compared to an expert panel. Moreover, as noted by the US Preventive Services Task Force (see Petitti et al51), clinicians “indicate frustration with the lack of guidance”p 199 when the Task Force fails to make recommendations. “Decision makers do not have the luxury of waiting for certain evidence. Even though evidence is insufficient, the clinician must still provide advice, patients must make choices, and policy makers must establish policies.”51, p 202

The synthesized findings of the 21 included reviews reveal the limited quantity and quality of evidence available to inform decisions about youth suicide prevention policies and programs. To date, no school-based intervention has demonstrated reduced rates of death by suicide in an RCT or CCS although reductions in suicide attempts and suicidal ideation, and other proxy measures of suicide risk have been reported. Findings for interventions relevant to the prevention of repeat suicide attempts also reveal the lack of RCTs and knowledge gaps regarding impact on death by suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. We were unable to draw conclusions about sex or gender differences in intervention effectiveness because none of the reviews addressed this issue systematically. The absence of reviews addressing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis as a special population also emerged as a major gap, and contrasts with recent reports of ongoing community and culture-based interventions for these youth in Canada.52 We found little or no consideration of the potential harms of suicide prevention interventions in the eligible reviews. The recent RCT reporting a trend for increased suicidal ideation among Aboriginal people who receive ASIST (Applied Suicide Intervention Skills) gatekeeper training (that is, the gatekeepers) illustrates the need to evaluate both the benefits and the harms of interventions before widespread use.53 No review addressed questions related to cost-effectiveness.

Although significant gaps exist, the findings suggest that interventions to increase contact between youth and trained professionals working in schools or effective systems of care show promise in preventing SRB. For example, school-based suicide awareness curricula plus screening (that is, Signs of Suicide) and skills training (that is, Good Behaviour Game) have been shown to reduce suicide attempts and (or) suicidal ideation in RCTs. For youth who have attempted suicide at least once and seek care, ED interventions that include postdischarge follow-up may reduce death by suicide. Training primary care professionals to provide evidence-based care for adolescent depression may reduce suicide attempts.34 Increased access to treatment of depression with antidepressants is also a potentially effective youth suicide prevention strategy. Preventing repeat suicide attempts in youth who do not seek care (that is, most youth with one or more suicide attempt) emerged as a challenging problem, with little available research. Interventions to increase help seeking behaviour by these youth may reduce risk for repeat suicide attempts. Effective postvention may also decrease the risk of contagion or copycat factors that result in repeated suicide attempts, as suggested by the recent Canadian study that documented an increased risk of suicidality outcomes in youth exposed to suicide.54 However, currently, both strategies require focused intervention development and evaluation.

Potential EKS limitations include the following. First, systematic review of review methods rely on existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses that may be subject to incorrect reporting and interpretation of primary studies, omission of important primary studies, and inclusion of poor-quality primary studies by review authors. We addressed these issues as follows. When reviews disagreed, the primary study was examined to determine whether the disagreement was factual or due to different interpretations of the same results. All appeared to be factual misinterpretations. Regarding omitted studies, both primary studies nominated by EAG members were included in the eligible high-quality reviews. The inclusion of low-quality uncontrolled studies in some reviews was addressed by limiting our conclusions to findings based on RCTs or CCSs. A second limitation concerns the scarcity of RCTs of youth suicide prevention interventions. We have noted the few available RCTs in our findings and recommendations. Third, it is unclear whether available youth suicide prevention interventions prevent death by suicide. This gap is due, in part, to the large sample size needed to study low event rates, and hence the need for adequately powered, multi-centre studies.

Conclusion

The 6 recommendations derived from our findings provide guidance to decision makers concerning school-based interventions and the prevention of repeat suicide attempts. They also provide the foundation for an evidence-informed action plan for Canada. The sixth recommendation, which calls for a national network of youth suicide research to practice centres, could position Canada as a leader in youth suicide prevention. Through the dissemination of what is known about effective, ineffective, and harmful prevention interventions, and the implementation of promising strategies linked to rigorous evaluation, the network could provide the leadership needed to clarify prevention intervention effects on death by suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation, strengthen our understanding of sex and (or) gender differences, address the unique needs of Aboriginal youth, and accordingly, promote and protect the health and well-being of Canadian youth and their families.

Acknowledgments

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funding for this project (EKT-121928). Dr Manassis reports royalties for several mental health books from Routledge, Guilford Press, and Barron’s Educational Series Inc. Dr Santos reports piloting and evaluating several programs reviewed in this manuscript, specifically, Good Behaviour Game, Signs of Suicide, and Sources of Strength, as part of Manitoba’s youth suicide prevention strategy (funded by the government of Manitoba). The remaining authors report no potential or perceived conflicts of interest. The authors thank Amanda Easson, Kristina Vukelic, and Judi Winkup for providing research support.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR

a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews

- CBT

cognitive-behavioural therapy

- CCS

controlled cohort study

- EAG

expert advisory group

- ED

emergency department

- EKS

expedited knowledge synthesis

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SRB

suicide-related behaviour

References

- 1.Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374:881–892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada . Leading causes of death, total population, by age group and sex, Canada [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2009. CANSIM Table 102–0561. [cited 2014 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=1020561&paSer=&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=-1&tabMode=dataTable&csid=. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behaviour surveillance—United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(4):1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol (New York) 1996;3(1):25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nock MK, Greif Green J, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SMARTRISK . The economic burden of injury in Canada. Toronto (ON): SMARTRISK; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parliament of Canada . House of Commons. An act respecting a federal framework for suicide prevention. Bill C-300, 41st Parliament, 1st Session, 2011–2012. Ottawa (ON): Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2012. 1st reading, 2011 Sep 29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K, Harriss L. Deliberate self-harm in young people: characteristics and subsequent mortality in a 20-year cohort of patients presenting to hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1574–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Gender and Health . What a difference sex and gender make. A gender, sex and health research casebook. Vancouver (BC): CIHR Institute of Gender and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. 2010;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: integrated and end-of-grant approaches. Ottawa (ON): CIHR; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [Internet] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [cited 2011 Feb 6; updated 2011 Mar]. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(10) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, et al. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [Internet] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [cited 2011 Feb 6; updated 2011 Mar]. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, et al. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(9):979–983. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.9.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ploeg J, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. A systematic overview of adolescent suicide prevention programs. Can J Public Health. 1996;87(5):319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbey KJ, Madsen CH, Polland R. Short-term suicide awareness curriculum. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1989;19:216–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1989.tb01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DN, Eckert TL, Mazza JJ. Suicide prevention programs in the schools: a review and public health perspective. School Psychol Rev. 2009;38(2):168–188. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takada M, Shima S. Characteristics and effects of suicide prevention programs: comparison between workplace and other settings. Ind Health. 2010;48:416–426. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cusimano MD, Sameem M. The effectiveness of middle and high school-based suicide prevention programmes for adolescents: a systematic review. Inj Prev. 2011;17(43):43–49. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.025502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz C, Bolton S, Katz LY, et al. A systematic review of school-based suicide prevention programs. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):1030–1045. doi: 10.1002/da.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aseltine RH, Jr, DeMartino R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):446–451. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aseltine RH, Jr, James A, Schilling EA, et al. Evaluating the SOS suicide prevention program: a replication and extension. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilcox HC, Kellam SG, Brown CH, et al. The impact of two universal randomized first- and second-grade classroom interventions on young adult suicide ideation and attempts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(Suppl 1):S60–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaac M, Elias B, Katz LY, et al. Gatekeeper training as a preventative intervention for suicide: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(4):260–268. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyman PA, Brown CH, LoMurray M, et al. An outcome evaluation of the Sources of Strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1653–1661. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Kleinman M, et al. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1635–1643. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton AS, Hamm MP, Bethell J, et al. Pediatric suicide-related presentations: a systematic review of mental health care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.026. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfaff JJ, Acres JG, McKelvey RS. Training general practitioners to recognise and respond to psychological distress and suicidal ideation in young people. Med J Aust. 2001;147:222–226. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall WD, Lucke J. How have the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants affected suicide mortality? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:941–950. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior. Behav Modif. 2008;32(1):77–108. doi: 10.1177/0145445507304728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Leigh E, et al. Practitioner review: self-harm in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson J, Hetrick SE, Martin C. Preventing suicide in young people: systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(1):3–26. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.511147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner RM. Naturalistic evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2000;7:413–419. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawton KKE, Townsend E, Arensman E, et al. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate self-harm (review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD001764. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crawford MJ, Thomas O, Khan N, et al. Psychosocial interventions following self-harm: systematic review of their efficacy in preventing suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:11–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corcoran J, Dattalo P, Crowley M, et al. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for suicidal adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33:2112–2118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daigle MS, Pouliot L, Chagnon F, et al. Suicide attempts: prevention of repetition. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(10):621–629. doi: 10.1177/070674371105601008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burns J, Dudley M, Hazell P, et al. Clinical management of deliberate self-harm in young people: the need for evidence-based approaches to reduce repetition. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:121–128. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hepp U, Wittmann L, Schnyder U, et al. Psychological and psychosocial interventions after attempted suicide: an overview of treatment studies. Crisis. 2004;25(3):108–117. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.25.3.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slee N, Garnefski N, Van Der Leeden R, et al. Cognitive-behavioural intervention for self-harm: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:202–211. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn RA, Bilukha O, Crosby A, et al. Firearms laws and the reduction of violence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2 Suppl 1):40–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lott JR, Whitley JE. Safe-storage gun laws: accidental deaths, suicides and crime. J Law Econ. 2001;44(Suppl 2):659–689. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cummings P, Grossman DC, Rivara FP, et al. State gun safe storage laws and child mortality due to firearms. JAMA. 1997;278:1084–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petitti DB, Teutsch SM, Barton MB, et al. Update on the methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: insufficient evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:199–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE. Cultural continuity as a protective factor against suicide in First Nations youth. Horizons—a special issue on Aboriginal youth, hope or heartbreak: Aboriginal youth and Canada’s future. 2008;10(1):68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sareen J, Isaak C, Bolton S, et al. Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in First Nations community members: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:1021–1029. doi: 10.1002/da.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swanson SA, Colman I. Association between exposure to suicide and suicidality outcomes in youth. CMAJ. 2013;185(10):870–877. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breton J, Boyer R, Bilodeau H, et al. Is evaluative research on youth suicide programs theory-driven? The Canadian experience. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(2):176–190. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.176.24397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Rihmer Z. Suicide prevention programs through community intervention. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peña JB, Caine ED. Screening as an approach for adolescent suicide prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(6):614–637. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.6.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durkee T, Hadlaczky G, Westerlund M, et al. Internet pathways in suicidality: a review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:3938–3952. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8103938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Links PS, Hoffman B. Preventing suicidal behaviour in a general hospital psychiatric service: priorities for programming. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(8):490–496. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Macgowan M. Psychosocial treatment of youth suicide: a systematic review of the research. Res Soc Work Pract. 2004;14(3):147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 61.McMyler C, Pryjmachuk S. Do ‘no-suicide’ contracts work? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:512–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakinofsky I. Treating suicidality in depressive illness. Part 2: does treatment cure or cause suicidality? Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(6 Suppl 1):85S–101S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Möller H. Evidence for beneficial effects of antidepressants on suicidality in depressive patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:329–343. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]