Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the mental health care needs perceived as unmet by adults in Quebec who had experienced depressive and (or) anxious symptomatology (DAS) in the previous 2 years and who used primary care services, and to identify the reasons associated with different types of unmet needs for care (UNCs) and the determinants of reporting UNCs.

Method:

Longitudinal data from the Dialogue Project were used. The sample consisted of 1288 adults who presented a common mental disorder and who consulted a general practitioner. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was used to measure DAS, and the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire facilitated the assessment of the different types of UNCs and their motives.

Results:

About 40% of the participants perceived UNCs. Psychotherapy, help to improve ability to work, as well as general information on mental health and services were the most mentioned UNCs. The main reasons associated with reporting UNCs for psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions are “couldn’t afford to pay” and “didn’t know how or where to get help,” respectively. The factors associated with mentioning UNCs (compared with met needs) are to present a high DAS or a DAS that increased during the past 12 months, to perceive oneself as poor or to not have private health insurance.

Conclusions:

To reduce the UNCs and, further, to reduce DAS, it is necessary to improve the availability and affordability of psychotherapy and psychosocial intervention services, and to inform users on the types of services available and how to access them.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, mental health services needs and demand, longitudinal studies

Abstract

Objectif :

Évaluer les besoins de soins de santé mentale perçus comme étant non comblés par des adultes québécois qui ont eu une symptomatologie dépressive et (ou) anxieuse (SDA) dans les 2 années précédentes et qui ont utilisé des services de première ligne, et identifier les raisons associées à différents types de besoins de soins non comblés (BSNC) et les déterminants pour déclarer ces BSNC.

Méthode :

Les données longitudinales du projet Dialogue ont été utilisées. L’échantillon se composait de 1288 adultes qui présentaient un trouble mental commun et qui consultaient un omnipraticien. L’Échelle d’anxiété et de dépression hôpital a servi à mesurer la SDA, et le questionnaire des besoins de soins perçus a éclairé l’évaluation des différents types de BSNC et de ce qui les motivait.

Résultats :

Quelque 40 % des participants ont perçu des BSNC. La psychothérapie, l’aide à améliorer la capacité de travailler, ainsi que l’information générale sur la santé mentale et les services étaient les BSNC les plus souvent mentionnés. Les principales raisons associées avec la mention des BSNC pour la psychothérapie et les interventions psychosociales sont: « n’a pas les moyens de payer » et « ne savait pas comment ni où trouver de l’aide », respectivement. Les facteurs associés à la mention des BSNC (comparés aux besoins comblés) sont de présenter une SDA élevée ou une SDA qui a augmenté dans les 12 derniers mois, de se percevoir comme étant pauvre ou sans assurance-maladie privée.

Conclusions :

Afin de réduire les BSNC et du coup, de réduire la SDA, il est nécessaire d’améliorer l’offre et les moyens de se procurer des services de psychothérapie et d’interventions psychosociales, et d’informer les utilisateurs des types de services offerts et de la façon d’y accéder.

Common mental disorders, such as anxiety and depressive disorders, are highly prevalent in Canada, yet less than one-third of adults with anxiety disorders and one-half of adults with depressive disorders actually seek care for these conditions from health professionals.1,2 Among the professionals consulted for anxiety and depressive disorders, GPs are consulted most often,1 with over 20% of GPs’ medical consultations each week devoted to these disorders.3

However, being diagnosed with a mental disorder does not necessarily translate into a perception that there exists a need for mental health care. While a clinical needs assessment is generally guided by diagnostic criteria, epidemiologic studies, and psychometric criteria, the perception that there is a need for care—a key determinant of the consultation process for mental health reasons4—is influenced by a person’s perception of their own disorders, which is itself related to the level of psychological distress and functional impairment that they experience.4–6 In 2000, Meadows et al7 created a detailed questionnaire (that is, the PNCQ) to assess needs for care from the patient’s point of view. The PNCQ has been used previously in adults suffering from common mental health disorders,8–19 with studies revealing that, in industrialized countries, between 45% to 75% of patients with anxiety and depressive disorders consulting in primary care report that their needs are only partially met or completely unmet.12,13,16,20 Rates of met and unmet needs for care also vary by the type of perceived needs examined. For instance, over 80% of patients with common mental disorders report that their needs for medication are fully met, while only 5% report that such needs go completely unmet.12,13 In contrast, while psychotherapy is reported to be the most frequent perceived need regarding mental health care,14 such needs are fully met in only one-half of patients10,12,14 and completely unmet in 13% to 26% of patients.12,13 Other perceived needs, such as those related to health information and psychosocial interventions (for example, related to housing or employment), are also less frequently fully met.12–14 However, only a few studies have focused on the predictive factors of the UNCs,14,15 with these studies only revealing that there is a link between declaring UNCs and suffering from a severe mental disorder or from psychological distress.18,20

Clinical Implications

Our study shows a link between the level of need perceived as met or unmet and the evolution of a patient’s mental health condition.

Affordability of psychotherapy remains a major issue, although it is recommended by clinical practice guidelines.

Knowing that one of the major goals of primary care is to reduce health inequalities, specific attention must be focused on the economically disadvantaged so that they can better access services.

Limitation

Unmet needs are declarative and only measured from the patient’s point of view. The study does not permit us to completely apprehend the temporality between the DAS, the perceived need, and the moment when the service may have been received.

Addressing UNCs, and particularly unmet treatment needs, is important, as people with untreated anxiety or depressive disorders are at higher risk of experiencing poor outcomes and recurrence of these disorders.19,21,22 Further, the human and economic costs of such disorders are high, especially when patients are inadequately treated.23–25

The objectives of the current study were to examine UNC in a cohort of primary care patients that had experienced DAS in the previous 2 years and to identify the reasons associated with different types of unmet needs and the determinants of reporting UNCs. A better understanding of these issues could help identify patients particularly prone to UNCs, and could potentially lead to a better allocation of resources in primary care.14,26

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Our study uses data from the Dialogue project (2006–2010), a large, multi-component study that included a longitudinal cohort study examining the care experiences and mental health status of primary care patients with DAS in 15 local service network territories in the province of Quebec.27 The cohort study was carried out in 4 phases, namely, an initial screening in the waiting rooms of 67 primary care clinics (T0) followed by 3 follow-up surveys carried out at 6-month intervals (T1, T2, and T3). The recruitment procedures are described fully elsewhere.27,28

Briefly, recruitment for the initial screening took place between March and August 2008. Participants were eligible if they met the following criteria: aged 18 years or older; able to speak either French or English; seeking care for themselves from a GP, regardless of the reason; and their regular source for care was a clinic participating in the study. Among the 22600 eligible people encountered, 14833 completed the whole screening questionnaire (not only the PNCQ). Within 2 to 4 weeks of the screening questionnaire, 3382 eligible participants were contacted for a first telephone or web-based interview (T1). Participants completed the full interview and were eligible for entry into the cohort if they met the following criteria: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnostic criteria for at least 1 of 5 common mental disorders in the previous 12 months (major depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, or social phobia) as assessed by the CIDI Simplified,29 a short-form version of the CIDI, especially designed to be used in mail or telephone surveys, which has satisfactory reliability and internal consistency; or met criteria for one of the above diagnoses in the previous 24 months, as well as reported receiving a diagnosis for an anxiety or depressive disorder from a health professional in the previous 12 months, or reported medication use for 1 of the disorders in the previous 12 months, or during the previous week, demonstrated a high level of DAS (≥8 out of 21 per subscale) as measured by the HADS30; or a high level of anxious or depressive symptoms during the previous week, as well as reported medication use for 1 of the disorders in the previous 12 months, or reported receiving a diagnosis for an anxiety or depressive disorder from a health professional in the previous 12 months.

In total, 1956 people met these criteria and participated in the T1 interview. These people were then contacted again 6 months (T2, n = 1476) and 12 months (T3, n = 1288) later. The final sample for our study is composed of the 1288 participants who completed the T3 interview (online eAppendix 1).

Our study received approval from the research ethics committee of the Agence de santé et des services sociaux de Montréal and all regional authorities in the project. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Needs for care were assessed at T1, T2, and T3 using the PNCQ developed by Meadows et al7 as part of the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. The PNCQ measures needs for care related to common mental disorders, as well as the reasons associated with unmet needs, from the patient’s perspective. The types of needs assessed related to the following: information on mental disorders, and on the available treatments or services; medication; psychotherapy or counselling; and psychosocial interventions (that is, help related to housing, finances, employment, self-care, social supports, or other interventions). The PNCQ has been used extensively in populations with common mental disorders8–19 and has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity, with interrater reliabilities generally exceeding kappas of 0.6 and a multi-trait, multi-method approach lending support to the instrument’s construct validity.7,31 Three somewhat different versions of the PNCQ were used, depending on the time of execution. The T1 questionnaire asked whether the respondent perceived that their needs were met, unmet, or whether they did not perceive any needs at all in the previous 12 months. Questionnaires at T2 and T3 measured 4 levels of needs during the 6-month period preceding the interview: no needs, needs fully met, needs partially unmet, or needs totally unmet. The reasons associated with perceived UNCs were based on a list of 7 to 12 multiple-choice questions, with the number of questions depending on the interview. Five of 7 essential items of the PNCQ were investigated at each interview: “preferred to manage yourself,” “thought nothing could help,” “didn’t know how or where to get help,” “were afraid to ask for help/what others would think,” and “couldn’t afford to pay.” Nine other reasons were explored in only 1 or 3 of the 3 interviews.

Regarding measuring DAS, the HADS was used at T0, T2, and T3. The HADS consists of 2 subscales, 1 for anxiety symptoms and the other for depressive symptoms, each comprising 7 items. Each item is rated from 0 (no symptoms) to 3 (high severity). For each subscale, the cutoff score—8 or higher out of 21—corresponds to a probable anxiety or depressive disorder.32 This score was used in the English and French versions of the HADS to demonstrate good psychometric properties.33–35

Finally, participants’ sociodemographic information (age, sex, education, marital status, perceived level of income, occupational status, urbanicity, whether the subject has a family doctor, and whether the subject has private insurance) was collected at T0 and T1.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to assess rates of met needs and UNCs at each interview time period. Analyses related to types of needs were based solely on data obtained during the T3 interview. Reasons for UNCs related to health information and medication were analyzed using data from the T2 questionnaire, as these sections do not appear in the T3 interview.

Reasons for UNCs related to psychotherapy and each type of psychosocial intervention were analyzed using data collected at T3 because, in this interview, respondents could provide reasons for UNCs related to each type of psychotherapy or psychosocial service listed. Bivariate analyses were performed by cross-tabulating the UNCs related to health information, and those related to medication, with the different reasons proposed at T2. Lastly, at T1 there was one open-ended question related to reasons for UNCs beyond those proposed in the PNCQ; this was the only interview that included this type of question.

We examined the determinants of UNCs using multivariate logistic regression analyses based on needs for care identified during the T3 interview. People who did not receive services and who had not expressed any need for care were excluded from the analysis. The dependent variable was dichotomous: UNCs (either partially or totally unmet) compared with fully met needs. Selected independent variables were based on the literature,11,14,15,20,34,36,37 and included sociodemographic characteristics and the evolution of DAS according to the overall HADS score. The sociodemographic variables included marital status, perceived level of income, education level, occupational status, whether the subject has a family doctor, and whether the subject has private insurance. The evolution of DAS between T0 and T3 comprised 4 categories: low DAS at both time periods; high DAS at both time periods; high DAS at T0 and low DAS at T3 (indicating improved mental health); and low DAS at T0 and high DAS at T3 (indicating a deterioration in mental health).

Variables significant at a threshold of P ≤ 0.2 in bivariate analysis were included in the model. Associations were expressed as odds ratios with their confidence intervals. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics, version 19, software.38

Results

Sample Description

The sample of 1288 primary care patients with DAS was comprised mainly of women (74.7%) and had a mean age of 44 years (Table 1). Most patients lived with a partner (56.1%), in urban areas (54.4%), with a level of education at or above high school (54.6%), perceived themselves as having sufficient income or were financially comfortable (75.6%), and had access to private health insurance (69.3%) and a regular family doctor (84.9%). Close to 80% of the people who were part of the sample had a high DAS at T0, whereas this was the case for only 52% of patients at T3.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of T3 respondents to the Dialogue Project survey, Quebec, 2008, n = 1288

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex, female | 962 (74.7) |

| Age, years | |

| 18 to 24 | 78 (6.1) |

| 25 to 44 | 470 (36.5) |

| 45 to 64 | 594 (46.1) |

| ≥65 | 146 (11.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or cohabiting | 723 (56.1) |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 280 (21.7) |

| Single | 283 (22.0) |

| Education | |

| ≤High school | 583 (45.3) |

| College | 343 (26.6) |

| University | 361 (28.0) |

| Urbanicity | |

| Predominantly urban area | 701 (54.4) |

| Intermediate area | 481 (37.3) |

| Rural area | 106 (8.2) |

| Occupational status | |

| Full-time work or studies | 622 (48.3) |

| Inactive or part-time work | 471 (36.6) |

| Retired | 195 (15.1) |

| Perceived level of income | |

| Financially comfortable | 218 (16.9) |

| Sufficient income | 756 (58.7) |

| Poor or very poor | 314 (24.4) |

| Has private health insurance | 892 (69.3) |

| Has a family doctor | 1094 (84.9) |

| DAS evolution between T0 and T3 | |

| Low DAS level at both phases | 174 (13.6) |

| High DAS level at both phases | 577 (45.0) |

| Decreasing DAS level (improving mental health) | 448 (34.9) |

| Increasing DAS level (deteriorating mental health) | 84 (6.5) |

Owing to missing data, the total percentage may not add up to 100%

DAS = depressive and (or) anxiety symptomatology

Perceived Needs for Care

At T1, 29% of the participants reported UNCs in the previous 12 months (Table 2). At T2 and T3, UNCs in the previous 6-month time periods were at about 40% (44% and 40%, respectively). When needs are unmet, they are often totally unmet. At T3, 36% of patients reported totally unmet needs since T2, 4% reported that their needs were partially unmet, and 32% perceived their needs as met. Across the 3 time periods, between 56% and 71% of the patients perceived either that they had no needs or that their needs had been met.

Table 2.

Prevalence of needs perceived as met, and partially or fully unmet at the 3 phases of the Dialogue Project survey, Quebec, 2008, n = 1288

| Perceived needs | UNC at T1 | UNC at T2 | UNC at T3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| n (%) | 95% CI | n (%) | 95% CI | n (%) | 95% CI | |

| No need or need met | 907 (71.0) | 68.3 to 73.3 | 718 (55.8) | 53.1 to 58.5 | 774 (60.1) | 57.4 to 62.8 |

| Need fully met | n/a | n/a | 412 (32.0) | 29.4 to 34.5 | 415 (32.2) | 29.7 to 34.8 |

| UNC (partially or fully) | 374 (29.0) | 26.6 to 31.5 | 570 (44.3) | 41.5 to 47.0 | 514 (39.9) | 37.2 to 42.6 |

| Partially UNC | n/a | n/a | 65 (5.0) | 3.9 to 6.2 | 55 (4.3) | 3.2 to 5.4 |

| Total UNC | n/a | n/a | 505 (39.2) | 36.5 to 41.9 | 459 (35.6) | 33.1 to 38.3 |

| Total | 1288 (100) | 1288 (100) | 1288 (100) | |||

n/a = not applicable or not available; UNC = unmet need for mental health care

Types of Unmet Needs

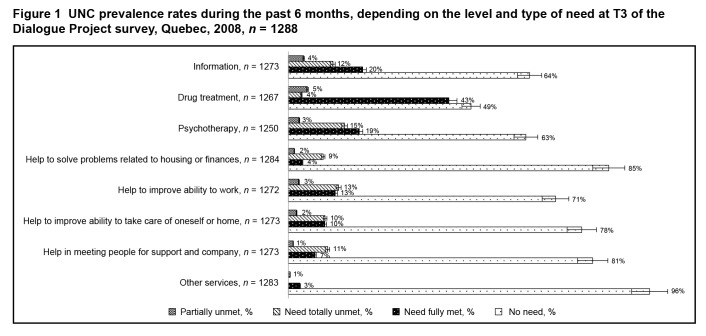

The types of UNCs—either partially or totally unmet—most mentioned by patients were related to psychotherapy, help related to employment, health information, and other services (Figure 1). A range of 71% to 85% of patients reported no need for psychosocial interventions. Lastly, the needs most frequently met related to needs for medication.

Figure 1.

UNC prevalence rates during the past 6 months, depending on the level and type of need at T3 of the Dialogue Project survey, Quebec, 2008, n = 1288

Reasons for Unmet Needs

The reasons given for UNCs vary by the type of need (Table 3). For patients reporting information needs at T1, the reasons relate mostly to accessibility issues: didn’t know how or where to get help, and unavailable services (48% and 30%, respectively). Two reasons were significantly associated with the needs for medication at T1: “couldn’t afford to pay” and “preferring to manage by oneself” (55% and 48%, respectively). At T3, the main reasons associated with unmet needs for psychotherapy consisted of “couldn’t afford to pay” or “preferring to manage by oneself” (29% and 23%, respectively).

Table 3.

Motive prevalence depending on the type of unmet need of care (UNC) in the Dialogue Project survey, Quebec, 2008, T1 n = 374; T3 n = 514

| Perceived reason | Informationa n (%) | Drug treatmenta n (%) | Psychotherapyb n (%) | Psychological interventions b | Any services n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Housing and finances n (%) | Working n (%) | Care n (%) | Support n (%) | |||||

| Preferred to manage yourself | 120 (53.3) | 50 (47.6)c | 34 (23.4) | 15 (14) | 28 (20) | 22 (20.4) | 16 (15.2) | |

| Thought nothing could help | 59 (26.5)c | 42 (40.0) | 10 (6.9) | 13 (12.1) | 10 (7.1) | 2 (1.9) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Didn’t know how or where to get help | 128 (48.7)c | 57 (43.2) | 17 (11.7) | 28 (26.2) | 29 (20.7) | 25 (23.1) | 37 (35.2) | |

| Afraid to ask for help or of what others would think | 77 (34.1) | 43 (41.3) | 16 (11) | 13 (12.1) | 16 (11.4) | 7 (6.5) | 10 (9.5) | |

| Couldn’t afford to pay | 120 (52.9)c | 58 (55.2)c | 42 (29) | 12 (11.2) | 25 (17.9) | 27 (25) | 18 (17.1) | |

| Problems with things transportation, childcare, scheduling | 62 (27.8)c | 27 (26.0) | ||||||

| Professional help not available in the area | 40 (19.1) | 18 (18.2) | ||||||

| Professional help not available at time required | 65 (30.0)d | 27 (27.0) | ||||||

| Waiting time too long | 82 (36.9)c | 36 (34.6) | ||||||

| Didn’t get around to it or didn’t bother | 86 (38.2) | 36 (34.6) | ||||||

| Language problems | 4 (1.8) | 1 (1.0) | ||||||

| Personal or family responsibilities | 48 (21.4) | 24 (22.9) | ||||||

| You asked but didn’t get the help? | 15 (10.3) | 18 (16.8) | 17 (12.1) | 18 (16.7) | 7 (6.7) | |||

| You got help from another source? | 11 (7.6) | 8 (7.5) | 15 (10.7) | 7 (6.5) | 10 (9.5) | |||

| Other | 64 (29.1) | 32 (31.1) | ||||||

| Dissatisfaction with the servicese | 17 (4.5) | |||||||

| Service had not been given or was refusede | 15 (4.0) | |||||||

Respondents may have expressed several motives per service need as well as several service needs.

Needs mentioned by individuals having declared, among other things, 1 or more UNCs at T1

Main unmet need, declared at T3

P< 0.05;

P< 0.01

Response to the open-ended question at T1

Needs for information and drugs were questioned at T1, where the motives were posed for all of the needs

The main reason associated with UNCs related to psychosocial interventions consisted of not knowing where to look for help (from 21% to 35%, depending on the type of help). Regarding help to take care of oneself or home, or help to improve ability to work, there were 2 recurring reasons for UNCs: “couldn’t afford to pay” (25% and 18%, respectively) and “preferring to manage by oneself” (20%, in both cases). Lastly, the open-ended question revealed 17 responses associating UNCs—regardless of service type—and included dissatisfaction with the services received as well as 15 responses related to people being denied a service.

Factors Associated With Unmet Needs for Care

The factors associated with reporting UNCs at T3 (n = 915) are as follows: to have high DAS at both T0 and T3 (OR 4.0; 95% CI 2.5 to 6.3; P < 0.001) or DAS that increased between T0 and T3 (OR 2.8; 95% CI 1.4 to 5.3; P = 0.002), which suggests a deteriorating mental health (Table 4). UNCs were also associated with perceiving oneself as economically poor or very poor (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.4; P = 0.005) and not having private health insurance (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0 to 2.1; P = 0.04).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with perceiving an unmet need of care (UNC) or a met need at T3 in the Dialogue Project survey, Quebec, 2008, n = 915

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| DAS evolution between T0 and T3 | ||

| Low DAS level at both phases | 1.00 | |

| High DAS level at both phases | 3.98 (2.51 to 6.31) | <0.001 |

| Decreasing DAS level (improving mental health) | 0.86 (0.53 to 1.42) | 0.56 |

| Increasing DAS level (deteriorating mental health) | 2.75 (1.44 to 5.26) | 0.002 |

| Education | ||

| ≤High school | 0.91 (0.63 to 1.30) | 0.59 |

| College | 1.00 | |

| University | 0.88 (0.60 to 1.30) | 0.52 |

| Perceived level of income | ||

| Financially comfortable | 0.70 (0.47 to 1.05) | 0.08 |

| Sufficient income | 1.00 | |

| Poor or very poor | 1.66 (1.17 to 2.36) | 0.005 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Inactive or part-time work | 0.88 (0.63 to 2.11) | 0.44 |

| Full-time work or studies | 1.00 | |

| Retired | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.06) | 0.08 |

| Has private health insurance | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | |

| No | 1.45 (1.03 to 2.05) | 0.04 |

| Has a family doctor | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | |

| No | 1.27 (0.84 to 1.92) | 0.25 |

Tests of the multivariate model: R2 = 0.150; χ2 = 148.840, df = 11; P < 0.001

DAS = depressive or anxiety symptomatology

Discussion

The results of our study should be interpreted by considering the following limitations. First, respondents had a more positive socioeconomic and health care profile than typically observed in participants in population health surveys (regarding income and access to private health insurance and to a regular family doctor). Second, the PNCQ was applied differently across the 3 patient interviews, which limited our ability to evaluate trends over time in met needs and UNCs as well as in the reasons for UNCs. For example, that UNCs were higher at T2 and T3 than at T1 could be because the PNCQs used at T2 and T3 focused on the level of the need for each type of help, whereas questions posed at T1 were more general and included an open-ended question. At T2, because the questions addressing reasons for UNCs were asked in a multiple-choice format for all of the types of UNCs, it does not allow us to know, with certainty, the reasons associated with information and drugs. Third, the PNCQ evaluated perceived needs for care in periods of 6 and 12 months, whereas the HADS examined symptoms of depression and anxiety in a 1-week period. As such, associations between perceived UNCs and a patient’s DAS should be interpreted with caution. Lastly, UNCs were self-reported and may be subject to memory or social desirability biases.39

Despite these limitations, our study sheds important light on UNCs among primary care patients with anxiety and depressive disorders, with several notable findings. First, the odds of reporting UNCs were significantly higher among patients with high DAS at both T0 and T3, as well as patients with deteriorating mental health between these interviews. The results about the deterioration of mental health associated with UNCs in particular are consistent with the results on care needs that were professionally assessed.22 Several studies have also shown that people perceiving UNCs have symptoms that are more severe than people without perceived needs for care,20 as well as higher distress.40,41

Consistent with previous studies conducted in the general population and among users of primary care services,1,10,12–15,19 needs related to psychotherapy are more likely to be perceived as unmet, and needs for medication as met. This is consistent with a high psychotropic consumption in Quebec,1 where their access is easy (that is, cost and prescription). Needs for information on mental health and services are partially met. In Quebec, information on mental health is available in clinics; however, it seems to lack information on services, such as effective therapies and how to get access.1 Statistics for psychosocial interventions vary greatly, depending on the studies and the type of help,10,12,15,18 which seems to be related to the supply of these services and their levels of financial coverage in the countries studied.

Our study shows that “preferring to manage by oneself” is a reason associated with several types of UNCs, but not the main one, contrary to what most literature claims.1,8,18,36,42,43 This difference appears to be due to the methods of analysis where the T3 PNCQ asks about the main reason behind the UNCs, whereas the studies that are also leveraging PNCQ show the response rates to multiple-choice questions and do not usually distinguish between the types of needs.1,8,36,42–44 Additionally, it seems that the “prefer to manage by oneself” reason is secondary to other causes, notably not knowing where to look for help or experiencing financial difficulties.44–46 Among the reasons for UNC, “didn’t know how or where to get help” is often the most reported. However, it is difficult to propose actions related to this response, as it could be driven by various factors, including: is the care accessible or available? If so, do patients receive information regarding these services? Do patients understand their disease enough to seek out appropriate services? Clearly, this result points to a need for more research to better understand this particular reason for UNCs. Lastly, we can assume that if the reasons highlighted by the open-ended question (that is, “dissatisfaction with services” and “denied services”) had been presented as multiple-choice items, their prevalence would have likely been higher.

We also observed associations between perceived UNCs and not having private social insurance and perceiving oneself as economically poor or very poor. This suggests that financial barriers may have been a reason for UNCs related to psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions, as has been highlighted by other studies.1,14,45,47 In Quebec, these services are in short supply in the public sector. Psychotherapy can be sought in the private sector, but this is not reimbursed by public health insurance. Though private health insurance may cover psychotherapy, only one-third of Quebecers48 have such insurance. Surprisingly, almost 70% of our participants had access to private insurance yet still reported unmet needs in psychotherapy, which could indicate that their insurance did not cover an adequate number of therapy sessions (insurance usually covers 4 sessions, while clinical practice guidelines recommend a minimum of 6 sessions).49,50 Since 2007, a program consisting of dispatching psychologists to Local Community Services and Health Centres was deployed as part of the Quebec’s Mental Health Action Plan 2005–2010 launched by the Ministry of Health and Social Services.51 However, these public clinics only reach part of the population: in our sample, at least 22% of the respondents sought care from a Local Community Services and Health Centre, regardless of the reason, and the prevalence of the general population indicates that just 1.1% of adult Quebecers sought care from a Local Community Services and Health Centre for mental health disorders.1 Despite their effectiveness and that they are endorsed by practice guidelines,49,50 and despite the efforts initiated by Quebec’s Mental Health Action Plan,51 the economic barrier to psychotherapy access remains a major problem.

Conclusion

Our study shows a link between the level of need perceived as met or unmet and the evolution of the patient’s mental health condition.

To reduce UNCs and alleviate their human and economic impact with patients who consult in primary care, several solutions can be considered. It would be important to improve the accessibility to psychotherapy52,53 by making it a service included in universal health coverage. It would further allow treatment to be more available to people who are economically disadvantaged, thereby potentially contributing to the reduction of health inequalities.54

Further investigations into needs related to psychosocial interventions according to patients’ profiles are also warranted. Such studies should compare said needs to available services and to the degree of cost reimbursements in the areas where these people live.

Knowing that good communication between patients and health professionals is a determining factor in improving access to care,14,15 and that a patient’s choice regarding their treatment has a positive effect on the remission of the symptoms,54 it is imperative that patients be consistently asked about their needs and preferences and that a solution be jointly sought.14,55

Acknowledgments

The Dialogue Project was funded by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRSQ), the Institut national de santé publique du Québec, the Groupe interuniversitaire de recherche sur les urgences, and the Ministry of Health and Social Services of Quebec.

Dr Dezetter is funded by the Strategic Training Program in Transdisciplinary Research on Public Health Interventions: Promotion, Prevention and Public Policy, a partnership of the Institute of Population and Public Health and the Institute of Health Services and Policy Research of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Québec Population Health Research Network.

Dr Duhoux holds a Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé postdoctoral grant.

Research in Addictions and Mental Health Policy & Services (RAMHPS), the Analyse et Évaluation des Interventions en Santé, and the Groupe de Recherche sur l’Équité d’Accès et l’Organisation des Services de Première Ligne.

Dr Roberge holds a FRSQ Junior 1 new investigator award.

Dr Menear received PhD grants from the RAMHPS program, the CIHR, the University of Montreal, and the Transdisciplinary Understanding and Training on Research—Primary Health Care program.

Dr Fournier holds an Applied Public Health Chair on population mental health from the CIHR, the FRSQ, and the Ministry of Health and Social Services of Quebec.

Abbreviations

- CIDI

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- DAS

depressive and (or) anxious symptomatology

- GP

general practitioner

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- PNCQ

Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire

- UNC

unmet need for mental health care

References

- 1.Lesage A, Rhéaume J, Vasiliadis HM. Utilisation de services et consommation de médicaments liées aux problèmes de santé mentale chez les adultes québécois. Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes (cycle 1.2) Quebec (QC): Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasiliadis HM, Lesage A, Adair C, et al. Service use for mental health reasons: cross-provincial differences in rates, determinants, and equity of access. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(10):614–619. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleury M, Bamvita J, Tremblay J, et al. Rôle des médecins omnipraticiens en santé mentale au Québec. Montreal (QC): Douglas Mental Health University Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovess V, Lesage A, Boisguerin B, et al. Planification et évaluation des besoins en santé mentale. Paris (FR): Médecine-Sciences Flammarion; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broadbent E, Kydd R, Sanders D, et al. Unmet needs and treatment seeking in high users of mental health services: role of illness perceptions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(2):147–153. doi: 10.1080/00048670701787503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhaak PF, Prins MA, Spreeuwenberg P, et al. Receiving treatment for common mental disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(1):46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meadows G, Harvey C, Fossey E, et al. Assessing perceived need for mental health care in a community survey: development of the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35(9):427–435. doi: 10.1007/s001270050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Issakidis C, Andrews G. Service utilisation for anxiety in an Australian community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(4):153–163. doi: 10.1007/s001270200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joska J, Flisher AJ. The assessment of need for mental health services. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(7):529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0920-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meadows G, Liaw T, Burgess P, et al. Australian general practice and the meeting of needs for mental health care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(12):595–603. doi: 10.1007/s127-001-8199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meadows G, Burgess P, Bobevski I, et al. Perceived need for mental health care: influences of diagnosis, demography and disability. Psychol Med. 2002;32(2):299–309. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meadows GN, Burgess PM. Perceived need for mental health care: findings from the 2007 Australian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(7):624–634. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meadows GN, Bobevski I. Changes in met perceived need for mental healthcare in Australia from 1997 to 2007. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):479–484. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prins MA, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, et al. Health beliefs and perceived need for mental health care of anxiety and depression—the patients’ perspective explored. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(6):1038–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prins MA, Verhaak PF, van der Meer K, et al. Primary care patients with anxiety and depression: need for care from the patient’s perspective. J Affect Disord. 2009;119(1–3):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prins M, Meadows G, Bobevski I, et al. Perceived need for mental health care and barriers to care in the Netherlands and Australia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(10):1033–1044. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0266-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson A, Hunt C, Issakidis C. Why wait? Reasons for delay and prompts to seek help for mental health problems in an Australian clinical sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(10):810–817. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Beljouw I, Verhaak P, Prins M, et al. Reasons and determinants for not receiving treatment for common mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(3):250–257. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Beljouw IM, Verhaak PF, Cuijpers P, et al. The course of untreated anxiety and depression, and determinants of poor one-year outcome: a one-year cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prins M, Bosmans J, Verhaak P, et al. The costs of guideline-concordant care and of care according to patients’ needs in anxiety and depression. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Perceived need for mental health treatment in a nationally representative Canadian sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(10):643–651. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J. A longitudinal population-based study of treated and untreated major depression. Med Care. 2004;42(6):543–550. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000128001.73998.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370:859–877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim KL, Jacobs P, Ohinmaa A, et al. A new population-based measure of the economic burden of mental illness in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2008;28(3):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews G, Sanderson K, Slade T, et al. Why does the burden of disease persist? Relating the burden of anxiety and depression to effectiveness of treatment. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):446–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J. Perceived barriers to mental health service use among individuals with mental disorders in the Canadian general population. Med Care. 2006;44(2):192–195. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196954.67658.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duhoux A, Fournier L, Gauvin L, et al. Quality of care for major depression and its determinants: a multilevel analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):142. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duhoux A, Fournier L, Gauvin L, et al. What is the association between quality of treatment for depression and patient outcomes? A cohort study of adults consulting in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNab C, Meadows G. Brief assessment of perceived need for mental health care—development of an instrument for primary care use. Monash (AU): Southern Synergy, the Southern Health Adult Psychiatry Research Training and Evaluation Centre, Monash University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjelland I, Lie SA, Dahl AA, et al. A dimensional versus a categorical approach to diagnosis: anxiety and depression in the HUNT 2 study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(2):128–137. doi: 10.1002/mpr.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363–370. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberge P, Dore I, Menear M, et al. A psychometric evaluation of the French Canadian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a large primary care population. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackenzie CS, Pagura J, Sareen J. Correlates of perceived need for and use of mental health services by older adults in the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(12):1103–1115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin E, Goering P, Offord DR, et al. The use of mental health services in Ontario: epidemiologic findings. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(9):572–577. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.IBM Corp . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 190. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drapeau A, Boyer R, Diallo FB. Discrepancies between survey and administrative data on the use of mental health services in the general population: findings from a study conducted in Quebec. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:837. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lefebvre J, Cyr M, Lesage A, et al. Unmet needs in the community: can existing services meet them? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(1):65–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sunderland A, Findlay L. Besoins perçus de soins de santé mentale au Canada : résultats de l’Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes—Santé mentale 2012. Ottawa (ON): Statistique Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sareen J, Jagdeo A, Cox BJ, et al. Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(3):357–364. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2011;41(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fossey E, Harvey C, Mokhtari MR, et al. Self-rated assessment of needs for mental health care: a qualitative analysis. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(4):407–419. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chartier-Otis M, Perreault M, Belanger C. Determinants of barriers to treatment for anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2010;81(2):127–138. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 Pt 1):987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craske MG, Edlund MJ, Sullivan G, et al. Perceived unmet need for mental health treatment and barriers to care among patients with panic disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(8):988–994. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philipps K. Catastrophic drug coverage in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Parliamentary Information and Research Service; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. Introduction. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Canadian Psychiatric Association Guidelines Advisory Committee Clinical practice guidelines. Management of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(8 Suppl 2):9S–91S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ministère de la Santé et Services Sociaux du Québec (MSSS) Plan d’action en santé mentale 2005–2010. La force des liens. Quebec (QC): MSSS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perreault M, Lafortune D, Laverdure A, et al. [Barriers to treatment access reported by people with anxiety disorders] Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(5):300–305. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800508. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dezetter A, Briffault X, Ben Lakhdar C, et al. Costs and benefits of improving access to psychotherapies for common mental disorders. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2013;16:161–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être . Pour plus d’équité et de résultats en santé mentale au Québec. Quebec (QC): Gouvernement du Québec; 2012. Rapport d’appréciation de la performance du système de santé et de services sociaux 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322(7289):772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.