Abstract

Objective:

American data suggest a declining trend in the provision of psychotherapy by psychiatrists. Nevertheless, the extent to which such findings generalize to psychiatric practice in other countries is unclear. We surveyed psychiatrists in British Columbia to examine whether the reported decline in psychotherapy provision extends to the landscape of Canadian psychiatric practice.

Method:

A survey was mailed to the entire population of fully licensed psychiatrists registered in British Columbia (n = 623). The survey consisted of 30 items. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and psychotherapy practice patterns. Associations between variables were evaluated using nonparametric tests.

Results:

A total of 423 psychiatrists returned the survey, yielding a response rate of 68%. Overall, 80.9% of psychiatrists (n = 342) reported practicing psychotherapy. A decline in the provision of psychotherapy was not observed; in fact, there was an increase in psychotherapy provision among psychiatrists entering practice in the last 10 years. Individual therapy was the predominant format used by psychiatrists. The most common primary theoretical orientation was psychodynamic (29.9%). Regarding actual practice, supportive psychotherapy was practiced most frequently. Professional time constraints were perceived as the most significant barrier to providing psychotherapy. The majority (85%) of clinicians did not view remuneration as a significant barrier to treating patients with psychotherapy.

Conclusions:

Our findings challenge the prevailing view that psychotherapy is in decline among psychiatrists. Psychiatrists in British Columbia continue to integrate psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in clinical practice, thus preserving their unique place in the spectrum of mental health services.

Keywords: psychotherapy, psychiatric practice, survey, barriers, satisfaction

Abstract

Objectif :

Des données américaines suggèrent une tendance à la baisse de la prestation de psychothérapie par les psychiatres. Néanmoins, la mesure dans laquelle ces résultats se généralisent aux pratiques psychiatriques d’autres pays n’est pas claire. Nous avons interrogé des psychiatres de la Colombie-Britannique pour examiner si la baisse de la prestation de psychothérapie s’étend à l’ensemble de la pratique psychiatrique canadienne.

Méthode :

Un sondage a été posté à toute la population des psychiatres pleinement licenciés enregistrés en Colombie-Britannique (n = 623). Le sondage consistait en 30 items. Des statistiques descriptives ont servi à caractériser l’échantillon et les modèles de pratique de psychothérapie. Les associations entre variables ont été évaluées à l’aide de tests non paramétriques.

Résultats :

En tout, 423 psychiatres ont renvoyé le sondage, pour un taux de réponse de 68 %. Globalement, 80,9 % des psychiatres ont déclaré pratiquer la psychothérapie. Aucune baisse de la prestation de psychothérapie n’a été observée; en fait, il y a eu une augmentation de la prestation de psychothérapie chez les psychiatres qui ont commencé leur pratique dans les 10 dernières années. La thérapie individuelle était le format prédominant utilisé par les psychiatres. La principale orientation théorique la plus courante était psychodynamique (29,9 %). En ce qui concerne la pratique actuelle, la psychothérapie de soutien était la plus souvent pratiquée. Les contraintes de temps des professionnels étaient perçues comme étant l’obstacle le plus significatif à la prestation de psychothérapie. La majorité (85 %) des cliniciens ne voyaient pas la rémunération comme un obstacle significatif à traiter les patients par psychothérapie.

Conclusions :

Nos résultats remettent en question le point de vue dominant selon lequel la psychothérapie serait en baisse chez les psychiatres. Les psychiatres de la Colombie-Britannique continuent d’intégrer la psychothérapie et la pharmacothérapie dans la pratique clinique, préservant ainsi leur place unique dans le spectre des services de santé mentale.

Despite a growing evidence base for psychotherapy in the treatment of psychiatric disorders,1–6 American survey data suggest that the provision of psychotherapy by psychiatrists has been diminishing and that now only a small minority of psychiatrists provides psychotherapy to most of their patients.7–9 According to an analysis of over 14 000 patient visits to office-based psychiatrists in the United States, the proportion of appointments involving psychotherapy declined from 44.4% in 1995–1996 to 28.9% in 2004–2005, extending a trend observed since the mid-1980s.8,10 This significant decline in psychotherapy has been explained, at least in part, by features of the American health care system, which maintains financial disincentives to physicians practicing psychotherapy.8 The decline has also been correlated with the rapid and marked increase in the use of psychotropics,7,11 as well as with the expansion of neuroscience in psychiatry and the primacy of neurobiological models of illness.12 Therefore, it is often assumed that dwindling psychotherapy treatment by psychiatrists represents a general trend in psychiatry,12 and not one limited to the United States. Indeed, the notion that the average psychiatrist no longer treats patients with psychotherapy has become conventional wisdom, as illustrated in a recent New York Times article, “Talk Doesn’t Pay, So Psychiatry Turns Instead to Drug Therapy.”13

Nevertheless, in recent years, a scaling up of psychotherapy training expectations has also been witnessed, as standards for the accreditation of psychiatry residency programs in the United States and Canada require that residents are trained to be competent practitioners in several psychotherapies.14,15 Moreover, recent studies of psychiatry training programs indicate that psychotherapy remains integral to the identities and future practices of contemporary psychiatry residents.16,17 Most trainees surveyed in both the United States and Canada endorsed plans to practice psychotherapy after graduation. Whether these positive expectations translate to actual psychotherapy practice has not been empirically investigated. Despite strong, and often polarizing, opinions on the matter, there is a paucity of systematic empirical research on the role of psychotherapy in current psychiatric practice generally. Previous published studies have mostly relied on health services databases and have not surveyed psychiatrists directly about their use of psychotherapy.7,8,10,18 Our study aims to address this gap in the literature.

The main objectives of our present study were to examine whether the declining trend reported in the provision of psychotherapy by American psychiatrists extends to the landscape of Canadian psychiatric practice; to describe contemporary psychotherapy practice patterns of Canadian psychiatrists; and to identify factors that influence psychotherapy practices of Canadian psychiatrists. Based on recent surveys of psychiatry residents showing a strong identification with psychotherapy, coupled with the growing number of evidence-based psychotherapies, we hypothesized that there would be an increase in the provision of psychotherapy among psychiatrists who have graduated in the past decade.

Clinical Implications

Contemporary psychiatrists practice from a diversity of theoretical orientations; there is no predominant theoretical model of psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy practice among psychiatrists in Canada remains strong, and seems to be increasing among recent graduates.

Only a very small percentage of psychiatrists regularly provides couple, family, or group therapies, suggesting that it will be challenging to find psychiatrists able to mentor future trainees in these therapies.

Limitations

Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, trends over time or causality regarding the associations observed could not be assessed.

As this was a self-administered questionnaire, findings are based on psychiatrists’ self-report, without verification of their accuracy.

Method

We mailed a questionnaire to the entire population of fully licensed psychiatrists registered with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia (n = 623). A cover letter explaining the objectives of the study accompanied the questionnaire, along with a return-address stamped envelope. Psychiatrists on leave for any reason, or no longer residing or working in British Columbia, were excluded. We sent a follow-up letter and questionnaire to psychiatrists who had not responded to the initial mailing 1 month later, and repeated this once more, for a total of 3 survey waves. Envelopes were coded to track responders, but separated from the questionnaire on receipt, to preserve anonymity. The survey period spanned from July to October 2013. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia Ethics Review Board.

The questionnaire was pilot-tested to ensure clarity and consistency in the way questions were interpreted, and to estimate response time. Colleagues with a wide range of backgrounds and experience (for example, years in practice, practice orientations, sex, and use of psychotherapy) evaluated the questions and provided feedback. The questionnaire took 10 to 15 minutes to complete if participants practiced psychotherapy, but only about 5 minutes for nonpsychotherapists. The survey instrument consisted of 30 items, most of which were Likert-type questions, inquiring into the following 7 domains: demographics and practice background (for example, setting, years in practice); psychotherapy orientation and use of different modalities and formats; engagement in supervision and personal therapy; CME in psychotherapy; potential barriers to practice; satisfaction with training, skills, and practice; and, a final item, confidence in the effectiveness of psychotherapy, compared with medications, in treating chronic depression. (We chose chronic depression because despite being a commonly encountered condition, the evidence base to guide its treatment remains limited, and both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are defensible choices.) Four yes-or-no questions asked about whether respondents had currently treated patients, practiced psychotherapy, provided or received supervision, or had received personal therapy. Data pertaining to personal therapy, supervision, and CME were analyzed separately and are not reported here. Two open ended-questions invited respondents to comment on factors that have led to either an increase or decrease in their psychotherapy practice, and factors that would encourage them to provide more psychotherapy.

Standard descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and examine psychotherapy practice patterns. To further test our hypothesis that psychotherapy is not in decline among recent psychiatry graduates, we conducted a Kruskal–Wallis test to evaluate differences across multiple groups (years in practice), followed by Mann–Whitney U tests comparing recent graduates to older cohorts in their provision of psychotherapy alone. Additional exploratory analyses were conducted to identify factors that may influence psychotherapy practice patterns. Associations between categorical variables were evaluated using chi-square tests, Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to evaluate differences in ordinal variables across multiple groups, and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for between-group comparisons. Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare psychiatrists’ ratings of satisfaction with their psychotherapy and psychopharmacology skills, and confidence in the use of psychotherapy, compared with medications, in the treatment of chronic depression.

Results

A total of 423 psychiatrists returned the survey, yielding a response rate of 68%. Nonrespondents (n = 203) did not differ significantly from those who completed the survey in terms of sex and years since graduation from medical school. Survey respondents worked in a wide range of practice settings in 39 different urban and rural municipalities throughout British Columbia. The majority of psychiatrists (72%; n = 302) received their training from Canadian medical schools; the remaining 28% were trained in 29 different countries. Most (87%) completed residency training in Canada (n = 363). Years since graduation from medical school ranged from 6 to 62 (1951–2007), with a median of 29 and mean of 28.

Psychotherapy Practice

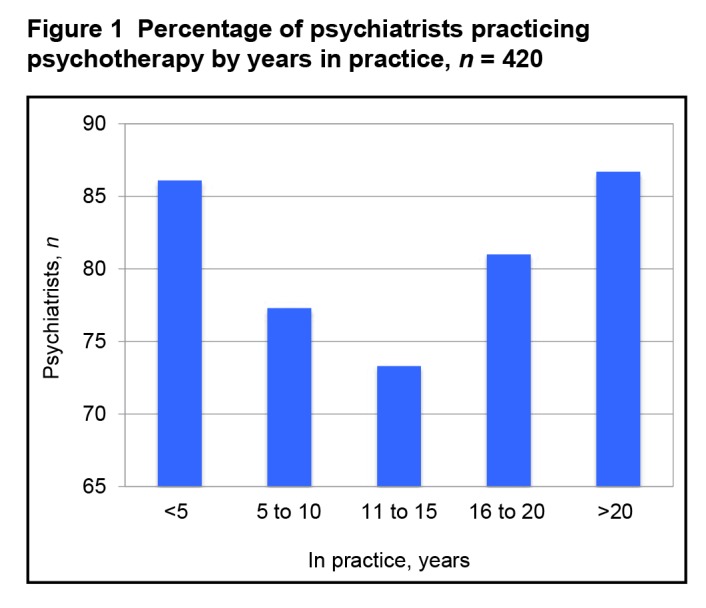

Overall, 80.9% of psychiatrists (n = 342) reported practicing psychotherapy; this figure increases to 82.8% if the denominator is limited to psychiatrists who are currently treating patients (n = 413, compared with 423). In keeping with our hypothesis, a decline in the provision of psychotherapy was not observed (Figure 1). In fact, there was an increase in psychotherapy among graduates entering practice in the last 10 years (86.1% of those who entered practice during the last 5 years endorse practicing psychotherapy, compared with 73.3% of psychiatrists in practice for 11 to 15 years). Among psychiatrists who practice psychotherapy, most provide psychotherapy combined with medications to most of their patients (only 18% never do so), while a much smaller proportion treat some patients with psychotherapy or medications alone. There was a significant difference across years in practice regarding the provision of psychotherapy alone (χ2 = 15.74, df = 4, P = 0.003). Follow-up Mann–Whitney U tests showed that psychiatrists who have been in practice for less than 5 years (U = 506.50, z = −1.95, P = 0.05) or more than 20 years (U = 2552, z = −2.39, P = 0.02) were significantly more likely to provide psychotherapy alone, compared with those in practice for 11 to 15 years.

Figure 1.

Percentage of psychiatrists practicing psychotherapy by years in practice, n = 420

Satisfaction With Psychotherapy Skills

Almost two-thirds of psychiatrists were satisfied (50.6%) or very satisfied (12.7%) with their skills in treating patients with psychotherapy, compared with 86% who were satisfied (60.8%) or very satisfied (25.2%) with their pharmacotherapy skills. The overall difference in satisfaction with their skills in psychotherapy, compared with pharmacotherapy, was statistically significant (z = −8.040, P < 0.001). We also found that psychiatrists’ satisfaction with their skills in treating patients with psychotherapy (χ2 = 30.83, df = 4, P < 0.001) and pharmacotherapy (χ2 = 13.91, df = 4, P = 0.008) differed significantly across years in practice. Psychiatrists who were in practice for more than 20 years were the most satisfied with their psychotherapy skills. Satisfaction with pharmacotherapy skills seemed to peak among psychiatrists in practice for 15 years, and then to decline slightly. Post hoc analyses showed that the difference between the oldest and youngest cohorts was statistically significant for satisfaction both with psychotherapy skills (U = 1844.5, z = −4.537, P < 0.001) and with pharmacotherapy skills (U = 2577.5, z = 2.163, P = 0.003).

There was a significant difference in psychiatrists’ confidence in psychotherapy, compared with pharmacotherapy, for the treatment of chronic depression (z = −6.945, P < 0.001). A greater proportion of psychiatrists expressed feeling moderately (52.6%) or extremely (10.8%) confident in the effectiveness of psychotherapy, compared with 33.7% and 9.3% who were moderately or extremely confident in pharmacotherapy, respectively. There was also a significant difference in psychiatrists’ confidence in the effectiveness of antidepressants in treating chronic depression across years of practice (χ2 = 14.63, df = 4, P = 0.006), with most recent graduates indicating the least confidence, but this was not the case for psychotherapy, in which psychiatrists were similarly confident across years in practice.

Therapeutic Orientation, Modalities, Formats

Individual therapy is the predominant format of psychotherapy currently practiced by psychiatrists (92.9% treat patients individually one-half or more of the time); couple, family, and group therapies are not commonly provided. Only 9.5% of psychiatrists practice couple therapy one-half or more of the time, while this is the case for 11.8% for group therapy and 18.1% for family therapy. Although the duration of treatment and frequency of follow-up visits was quite variable, only a small percentage of psychiatrists regularly treated patients for less than 3 months, and 49% provided long-term psychotherapy (>1 year) to at least one-half of their patients.

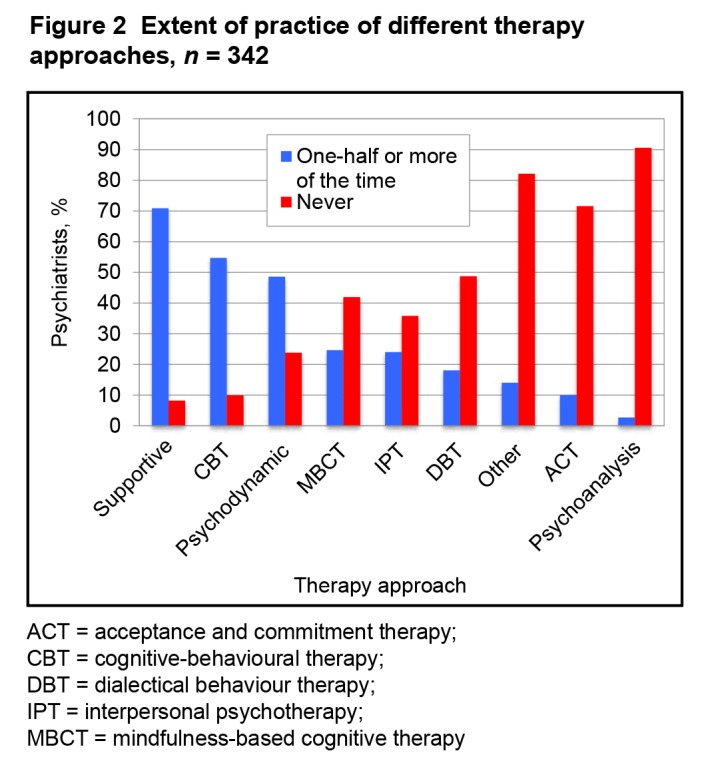

The most common primary theoretical orientations to psychotherapy were psychodynamic (29.9%), CBT (25.2%), supportive psychotherapy (20.5%), and other (15.8%), of which 10.5% consisted of an eclectic orientation. However, regarding actual practice (Figure 2), supportive psychotherapy and CBT were used most frequently; almost all clinicians employed these approaches to some extent. Interestingly, although psychodynamic psychotherapy was identified as the most common therapeutic orientation, almost one-quarter of psychiatrists indicated that they never treated patients with this approach. Most psychiatrists regularly used more than one form of psychotherapy; almost one-quarter (23.8%) practiced 3 or more kinds of psychotherapy at least one-half the time, while 88.8% did so at least some of the time, which is consistent with an eclectic or integrative practice pattern.

Figure 2.

Extent of practice of different therapy approaches, n = 342

ACT = acceptance and commitment therapy;

CBT = cognitive-behavioural therapy;

DBT = dialectical behaviour therapy;

IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy;

MBCT = mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

Barriers

Over two-thirds of respondents (70%) perceived professional time constraints as a moderate or extreme barrier to providing psychotherapy. Surprisingly, only 15% of psychiatrists felt this way about remuneration. Most psychiatrists also did not perceive level of training in psychotherapy (86.4%), maintaining long-term relationships with patients (85.6%), and emotional demands associated with psychotherapy (86.3%) as moderate or extreme barriers to practice. Eight per cent of psychiatrists identified other barriers that ranked as moderate or extreme; the most common among these were institutional pressure to assess and treat more patients and lifestyle choices. There was a significant difference across stages of experience regarding perceived level of training (χ2 = 23.77; df = 4, P < 0.001) and maintaining long-term relationships (χ2 = 17.54; df = 4, P = 0.002) as barriers to treating patients with psychotherapy, with the youngest cohort (less than 5 years in practice) considering these as more significant barriers. Perceived emotional demands, professional time constraints, and remuneration did not differ significantly across groups.

Forty-three per cent of clinicians indicated that various factors would encourage them to provide more psychotherapy. The most commonly identified factors included having more time or smaller caseloads, additional training and supervision, better remuneration, and institutional support to maintain a psychotherapy practice.

Influencing Factors

We explored the association between the provision of psychotherapy and the following variables: sex, work setting, satisfaction with psychotherapy skills, and confidence in the effectiveness of psychotherapy in treating chronic depression. To correct for multiple tests, a Bonferroni-adjusted P value of 0.013 was used. Although a greater proportion of male psychiatrists (84%) provided psychotherapy than female psychiatrists (76%), this was not significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons (χ2 = 4.08, df = 1, P < 0.04). Work setting was significantly associated with psychotherapy provision; clinicians working in private offices in the community were far more likely to practice psychotherapy (96%; χ2 = 43.89, df = 1, P < 0.001), while those working solely in hospital in-patient settings were the least likely to provide psychotherapy (44%; χ2 = 18.28, df = 1, P < 0.001).

Satisfaction with psychotherapy skills (χ2 = 46.354, df = 3, P < 0.001) and confidence in the effectiveness of psychotherapy (χ2 = 13.245, df = 4, P < 0.01) were positively associated with providing psychotherapy generally. Clinicians who practiced psychotherapy were also more likely to treat patients with psychotherapy alone if they endorsed greater satisfaction in their psychotherapy skills (χ2 = 72.32, df = 3, P < 0.001) and greater confidence in the effectiveness of psychotherapy for chronic depression (χ2 = 33.62, df = 4, P < 0.001). By comparison, neither satisfaction with pharmacotherapy skills nor confidence in the effectiveness of medications for chronic depression was significantly associated with psychotherapy provision.

Discussion

Our findings challenge the prevailing view that psychotherapy is in decline among psychiatrists generally. Instead, we found a U-shaped pattern showing that provision of psychotherapy was highest among both recent graduates and psychiatrists who have been in practice for more than 20 years. The persistent decline of psychotherapy by psychiatrists observed in the United States during the past 2 decades should not be interpreted as a general undervaluing of psychotherapy by the discipline of psychiatry, but as the result of constraining social and financial forces that may not have had the same impact on psychiatric practice in other countries such as Canada. In the absence of significant financial disincentives, psychotherapy practice among psychiatrists in British Columbia remains strong, and seems to be on the increase among recent graduates—a reassuring sign, given the growing evidence base for the efficacy of psychotherapy. This increase in psychotherapy provision is also reassuring in light of patients often preferring psychotherapy to medications; a recent meta-analysis found a 3-fold preference for psychological therapies, compared with pharmacotherapy, in the treatment of both depression and anxiety disorders.19 Psychiatrists who provide comprehensive psychiatric care can readily accommodate patient preferences, which is associated with better treatment retention and outcomes.19 Recent meta-analyses suggest that treatment with psychotherapies or pharmacotherapy for depression or anxiety disorders achieve comparable outcomes,1,4,19 and that for patients with severe and chronic illness courses, combination treatment may be advantageous.20,21 Adjunctive use of psychotherapy has also been shown to improve outcomes in more severe psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder22 and schizophrenia,23 which have historically been treated with pharmacotherapy and case management.

Our findings indicate that contemporary psychiatrists practice from a diversity of theoretical orientations; there was no predominant model of psychotherapy. Although the most common theoretical orientation endorsed by respondents was psychodynamic, this was the case for less than one-third of psychiatrists; the remainder practice from a range of perspectives, with CBT being the second most common. Most psychiatrists provide individual treatment, and only a very small percentage regularly provides couple, family, or group therapies. Given Canadian residency training requirements that graduating residents achieve proficiency in either family or group therapy,14 this low provision is concerning and suggests that it will be challenging to find psychiatrists able to mentor trainees in these therapies.

That psychiatrists are significantly less satisfied with their skills in psychotherapy, compared with pharmacotherapy, also has implications for residency training, especially given the lowest ratings observed among recent graduates. Although it is reasonable to assume that psychotherapy skills improve with experience, and that it may take years of practice after graduation to feel satisfied with one’s abilities, this may represent a cohort effect potentially reflective of less robust training in psychotherapy among recent graduates. Interestingly, while a linear relation emerged between years in practice and satisfaction with psychotherapy skills, this was not the case for pharmacotherapy skills, in which the highest satisfaction ratings were among psychiatrists who have been in practice for 15 years. Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, we are unable to determine trends over time or causality regarding the associations observed. As with any self-administered questionnaire, our findings are also entirely based on psychiatrists’ self-report, without verification of their accuracy. For example, although psychiatrists endorse practicing various structured, evidence-based psychotherapies, we do not know whether they adhere to established treatment protocols or how they structure their delivery of these treatments. Future research is needed to elucidate these issues.

This is the largest survey of psychiatrists inquiring into psychotherapy practices of which we are aware. Our 68% response rate compares favourably to previous surveys of psychiatrists,24,25 and exceeds expectations of response rates in physician surveys generally, which tend to be lower than the general population26 and have been declining for over a decade.27 A study of nonresponse rates in physician surveys across 17 medical specialties found that response rates ranged between 36% to 61%, with psychiatrists (40%) having the third lowest response rates.28 We did not find evidence of nonresponse bias in terms of sex and year of graduation. To increase the likelihood that psychiatrists not interested in psychotherapy participated in the survey, we designed the questionnaire to take less than 5 minutes for nonpsychotherapists to complete. Psychiatrists from 39 municipalities across the province and from a diverse range of practice settings responded to the survey, increasing confidence that our results are representative of psychiatrists throughout the province. The generalizability of this study to health care regions outside of British Columbia may be limited, as remuneration for psychotherapy varies across provinces in Canada. However, our findings are consistent with a previous Canadian study, which sampled psychiatrists from different provinces but still found that psychotherapy was central to the practice of psychiatrists, with 92% of psychiatrists spending just under one-half their time providing psychotherapy.29 The lower provision of psychotherapy among recent graduates found in that 2001 study corresponds with the bottom of the U-shape pattern we observed. Interestingly, they also found that psychiatrists who completed their training before 1984 were significantly more likely to practice psychotherapy, which is remarkably consistent with our results showing greater provision of psychotherapy by clinicians who have been in practice for more than 20 years, and parallels the psychotherapy practice of recent graduates.

According to our study, 86% of psychiatrists who graduated in the past 5 years practice psychotherapy. In a national survey of psychiatry residents that we conducted in 2007, 84% of graduating residents indicated that they anticipated providing psychotherapy in their professional practice.17 Similarly, a national survey in the US found that psychiatry residents viewed becoming a psychotherapist as integral to their identity as psychiatrists and had positive expectations of proving psychotherapy after they graduated.30 These findings suggest the possibility that psychotherapy provision by psychiatrists in the United States may potentially increase, especially given recent changes to residency training requirements by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education emphasizing evidence-based psychotherapies and achieving competence in psychotherapy as outcomes of training.14,31 However, an unpublished 2010 survey of US psychiatrists found that financial issues (80%) and administrative burdens (72%) were significant barriers to the provision of psychotherapy.32 In that study, only 10% of respondents treated patients with psychotherapy alone, while 49% solely provided medication treatment.32 Given a 14% response rate, the generalizability of their results is limited.

Conclusion

For over a decade, psychiatric educators have lamented the diminishing role of psychotherapy in psychiatric practice and the implication that psychotherapy is fading from psychiatrists’ professional identity.9,33,34 Commentators have alluded to a new generation of psychiatrists, who are more inclined to identify themselves as psychopharmacologists than to practice psychotherapy.9,35 Data from our study do not support this view. According to our findings, psychiatrists trained in the 1990s—the “decade of the brain”36,37—provide the least psychotherapy. This corresponds to a period in psychiatry, following the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, when biological approaches to treatment increasingly dominated the field.37 Luhrmann’s37 extensive ethnography of American psychiatry in the 1990s offers a rich description of how the erosion of psychotherapy in psychiatry related, at least in part, to its increasing allegiance to the neurosciences and psychopharmacology. However, in light of a growing body of research on the neurobiology of psychotherapy,38–40 dualist views on medications and psychotherapy—that the former are biologically based, while the latter only have psychological effects—are no longer tenable. Psychiatrists in British Columbia continue to integrate psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in clinical practice, and we anticipate that this integration will increasingly be informed by developments in social neuroscience, especially among many recent graduates whose interest in psychotherapy may have little to do with eschewing biological approaches.

Acknowledgments

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest or financial relationships to declare. Financial support for this study was provided by the Department of Psychiatry at the University of British Columbia through a start-up grant awarded to Dr Hadjipavlou.

Abbreviations

- ACT

acceptance and commitment therapy

- CBT

cognitive-behavioural therapy

- CME

continuing medical education

References

- 1.Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, et al. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):137–148. doi: 10.1002/wps.20038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leichsenring F, Rabung S. Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in complex mental disorders: update of a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):15–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shedler J. The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2010;65(2):98–109. doi: 10.1037/a0018378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spielmans GI, Berman MI, Usitalo AN. Psychotherapy versus second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(3):142–149. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31820caefb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoffers JM, Vollm BA, Rucker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD005652. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1456–1463. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in psychotherapy by office-based psychiatrists. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(8):962–970. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.8.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chisolm MS. Prescribing psychotherapy. Perspect Biol Med. 2011;54(2):168–175. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2011.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Pincus HA. Trends in office-based psychiatric practice. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(3):451–457. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: results from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;75(2):169–177. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabbard GO. Psychotherapy in psychiatry. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(1):5–12. doi: 10.1080/09540260601080813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris G. Talk doesn’t pay, so psychiatry turns instead to drug therapy. New York Times. 2011 Mar 6; Sect A:1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weerasekera P, Manring J, Lynn DJ. Psychotherapy training for residents: reconciling requirements with evidence-based, competency-focused practice. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(1):5–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.34.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manring J, Beitman BD, Dewan MJ. Evaluating competence in psychotherapy. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):136–144. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.3.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudak DM, Goldberg DA. Trends in psychotherapy training: a national survey of psychiatry residency training. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(5):369–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.11030057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadjipavlou G, Ogrodniczuk JS. A national survey of Canadian psychiatry residents’ perceptions of psychotherapy training. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(11):710–717. doi: 10.1177/070674370705201105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilk JE, West JC, Rae DS, et al. Patterns of adult psychotherapy in psychiatric practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(4):472–476. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595–602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association (APA). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. third edition. Arlington (VA): APA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(7):376–385. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1408–1419. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832–839. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826dd9af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alfonso CA, Olarte SW. Contemporary practice patterns of dynamic psychiatrists—survey results. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2011;39(1):7–26. doi: 10.1521/jaap.2011.39.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garfinkel PE, Bagby RM, Schuller DR, et al. Predictors of professional and personal satisfaction with a career in psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):333–341. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cull WL, O’Connor KG, Sharp S, et al. Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):213–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFarlane E, Olmsted MG, Murphy J, et al. Nonresponse bias in a mail survey of physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30(2):170–185. doi: 10.1177/0163278707300632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leszcz M, Mackenzie R, el-Guebaly N, et al. Canadian psychiatrists’ use of psychotherapy. Canadian Psychiatric Association Bulletin. 2002 Oct;:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanouette NM, Calabrese C, Sciolla AF, et al. Do psychiatry residents identify as psychotherapists? A multisite survey. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2011;23(1):30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellman LA, Beresin E. Psychotherapy competencies: development and implementation. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):149–153. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moran M. Survey identifies obstacles to psychotherapy by psychiatrists. Psychiatric News. 2012 Nov 2; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabbard GO, Kay J. The fate of integrated treatment: whatever happened to the biopsychosocial psychiatrist? Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):1956–1963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drell MJ. The impending and perhaps inevitable collapse of psychodynamic psychotherapy as performed by psychiatrists. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2007;16(1):207–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kontos N, Querques J, Freudenreich O. The problem of the psychopharmacologist. Acad Psychiatry. 2006;30(3):218–226. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabbard GO. Psychodynamic psychiatry in the “decade of the brain.”. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(8):991–998. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.8.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luhrmann TM. Of two minds: an anthropologist looks at American psychiatry. New York (NY): Vintage Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabbard GO. A neurobiologically informed perspective on psychotherapy. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:117–122. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Etkin A, Pittenger C, Polan HJ, et al. Toward a neurobiology of psychotherapy: basic science and clinical applications. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(2):145–158. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weingarten CP, Strauman TJ. Neuroimaging for psychotherapy research: current trends. Psychother Res. 2015;25(2):185–213. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.883088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]