Abstract

Patient: Male, 64

Final Diagnosis: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with pure squamous cell

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: —

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

In the United States, approximately 2500 cases of cholangiocarcinoma occur each year. The average incidence is 1 case/100 000 persons each year. Surgical resection is the mainstay for the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. The result of surgery depends on location of the tumor, extent of tumor penetration of the bile duct, tumor-free resection margins, and lymph node and distant metastases. There has been an increase in the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHCC) globally over a period of 30 years from 0.32/100 000 to 0.85/100 000 persons each year. Epidemiologically, the incidence of IHCC has been increasing in the U.S. from year 1973 to 2010.

Case Report:

We are reporting a first case of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of pure squamous cell histology. A 64-year-old man presented with right upper-quadrant pain, jaundice, and weight loss. Imaging studies revealed a large hepatobiliary mass, intrahepatic bile duct dilation, normal common duct, and absence of choledocholithiasis. Delayed-contrast magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed peripheral enhancement of the central lesion, which is typical of cholangiocarcinoma in contrast to hepatocellular carcinoma or metastasis. Cancer antigen 19-9 was markedly elevated. Liver function tests were deranged. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed high degree of left hepatic duct stricture. Brush cytopathology was positive for atypia. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy for en-bloc resection of the hepatobiliary mass with colon resection, liver resection, and cholecystectomy. Histology revealed keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Based on these findings, a definitive diagnosis of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the intrahepatic bile duct was made.

Conclusions:

Squamous cell carcinoma of the biliary tree is very rare and the majority of tumors are adenocarcinomas. Cholangiocarcinomas containing a squamous cell component have a poor prognosis due to its aggressive behavior. However, prognosis of cholangiocarcinoma with pure SCC histology is unknown because this is the first case in the literature.

MeSH Keywords: Adenocarcinoma; Carcinoma, Squamous Cell; Cholangiocarcinoma

Background

In the United States, approximately 2500 cases of cholangiocarcinoma occur each year. The average incidence is 1 case/100 000 persons each year. The result of surgery depends on the location of the tumor, extent of tumor penetration of the bile duct, tumor-free resection margins, and lymph node and distant metastases. Because 5% of the patients with CC have multifocal lesions, 50% of the patients have lymph node metastases and 10–20% of the patients have distant metastases at the time of presentation, the long-term survival with surgical management is not satisfactory [1]. Hepatobiliary cancers include hepatocellular cancer, gall bladder cancer, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHCC), and extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma. There has been an increase in the incidence of IHCC globally over a period of 30 years, from 0.32/100 000 to 0.85/100 000 persons each year. Epidemiologically, the incidence of IHCC has been increasing in the U.S. from year 1973 to 2010. Incidence-based mortality initially followed the similar trend of incidence, but after 1996 there has been a decline in mortality rates [2]. Squamous cell carcinoma of the biliary tree is very rare and the majority of tumors are adenocarcinomas [3]. Cholangiocarcinomas containing a squamous cell component have a poor prognosis due to its aggressive behavior. So far, there is no case report of IHCC with pure squamous cell histology; thus, the behavior of this cancer is unknown. Here, we report the first published case of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of pure squamous cell histology.

Case Report

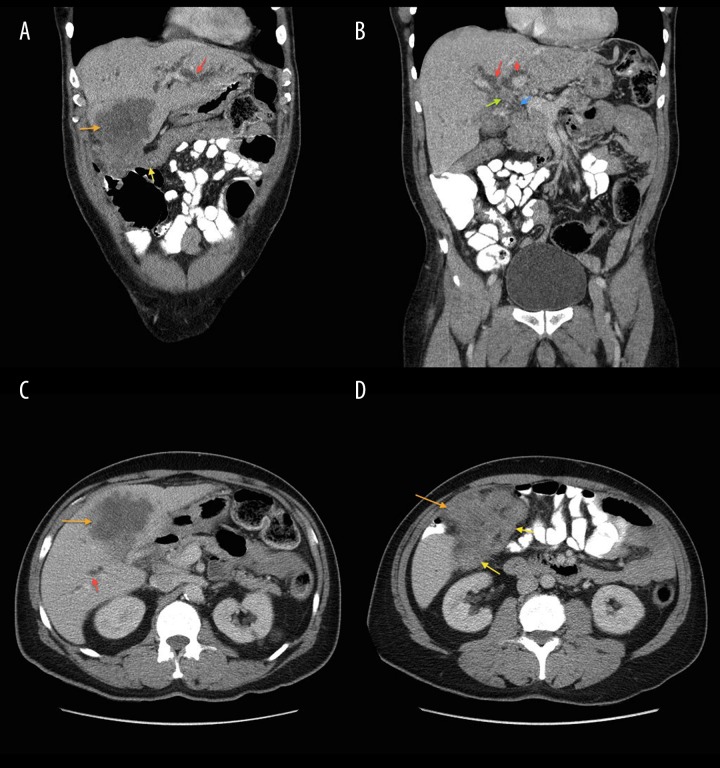

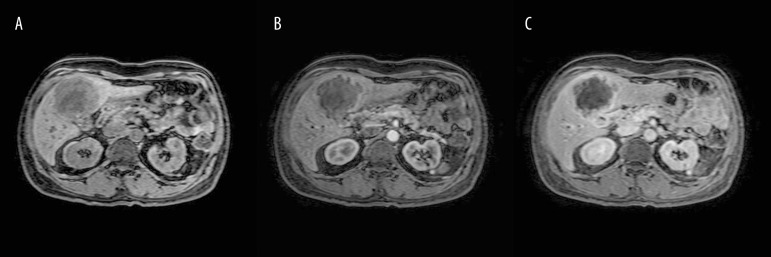

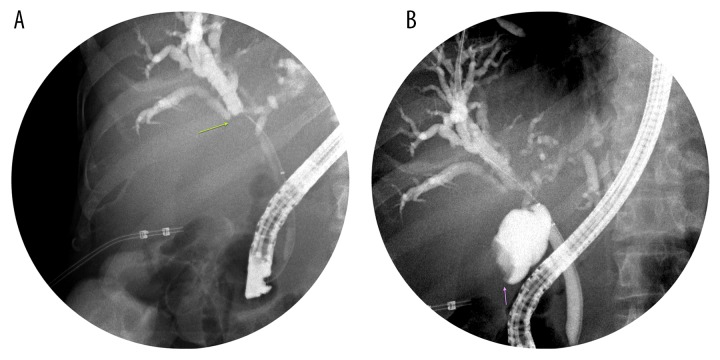

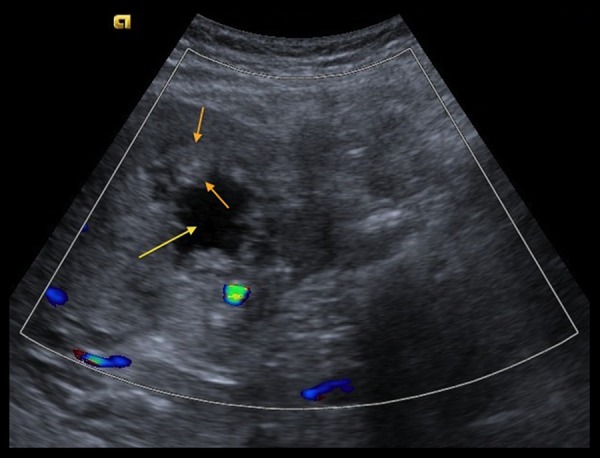

A 64-year-old man with past medical history of gall stones was admitted to our hospital with complaints of right upper-quadrant (RUQ) pain, yellowing of eyes, darkening of urine color, and pruritus for 3–4 days. The patient had lost approximately 40 pounds over the previous few months. Physical examination was remarkable for jaundice and mild RUQ tenderness. Liver function tests were abnormal with markedly elevated bilirubin (total bilirubin was 17.26 mg/dl, with conjugated bilirubin of 10.91 mg/dl). RUQ ultrasound (Figure 1) revealed significant intrahepatic bile duct dilation along with a 7.8×7.0 cm complex mass in the region of the gall bladder fossa and a 2.9×2.5 cm nodule adjacent to the complex mass. Cancer antigen 19-9 (Ca19-9) was >1300 units/ml (normal range: <41.3 units/ml). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen (Figure 2A–2D) demonstrated an enhancing mass at the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts and a normal caliber of the extra-hepatic bile duct. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed an 8.6×7.5×7.3 cm mass involving segment 5 of the liver, with intrahepatic bile duct dilation. Delayed contrast MRI abdomen images (Figure 3A–3C) showed peripheral enhancement of the central lesion, which is typical of cholangiocarcinoma, in contrast to hepatocellular carcinoma or metastasis. There was no choledocholithiasis, with normal common bile duct, and no abdominal lymphadenopathy. The findings were suspicious for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Figure 4A, 4B) performed on hospital day 3 showed a high level of stricture, mainly of the left hepatic duct. A biliary stent was placed for symptomatic relief. Bile duct brushing for cytopathology was positive for mild atypia. The follow-up levels of CA 19-9 and bilirubin 25 day after stent placement were significantly reduced (CA 19-9: 151.6 units/ml, total bilirubin: 3.06 mg/dl and conjugated bilirubin: 1.65 mg/dl). These levels were checked prior to the surgery.

Figure 1.

Trans-abdominal ultrasound image with color flow demonstrates an irregular, thick-walled (between orange arrows) mass in the region of the gallbladder fossa with cystic/necrotic center (yellow arrow). The wall of the mass lacks increased vascularity.

Figure 2.

(A–D) Selected images from contrast-enhanced CT abdomen demonstrate intrahepatic biliary dilation (red arrows). There is a heterogeneously enhancing mass in the liver that obscures the gallbladder (orange arrow), with extra-hepatic extension to the hepatic flexure of the colon (yellow arrow). Enhancing mass at confluence of left and right hepatic ducts (green arrow) and a normal-caliber extra-hepatic common bile duct (blue arrow).

Figure 3.

Pre-contrast (A), early arterial phase (B), and delayed phase (C) demonstrate delayed peripheral enhancement (bright white outline) around the liver mass.

Figure 4.

Two spot images (A, B) demonstrate dilated intrahepatic biliary ducts with a filling defect at the confluence of right and left hepatic ducts (green arrow), which was subsequently stented. There is also a filling defect in the fundus of the gallbladder (purple arrow).

The metastatic work-up was negative. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy for debulking surgery and had en-bloc resection of a hepatobiliary mass with colon resection, liver resection, and cholecystectomy. A chevron incision was made below the costal margin. A large necrotic mass was palpated in the RUQ, which was adherent to another mass in the liver and the hepatic flexure. The omentum was dissected free, which was also adherent to the necrotic mass. The lesser sac was entered and the dissection continued up towards the porta hepatis. The hepatobiliary mass was entered and bile was drained and sent for cytology. Only the outer wall of the hepatic flexure was divided using an Echelon stapler. End-to-end anastomosis was not needed. The hepatobiliary mass was sent to pathology and was consistent with carcinoma, likely squamous in origin. An earlier-dissected portal lymph node was sent to pathology, which was negative for metastatic carcinoma. The liver mass was also dissected and pathology was consistent with findings in the en-bloc resection previously sent.

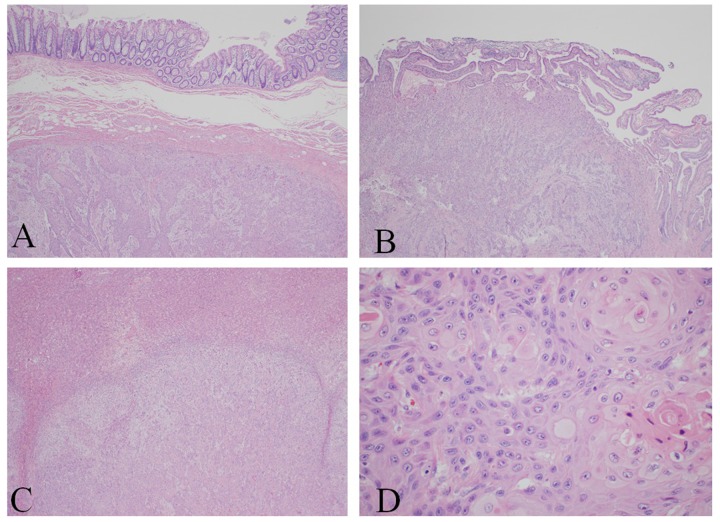

Pathologically, the tumor was present at the resection margins. Since the jaundice and bilirubin levels improved with the stent, it was left in place. The pancreas was not touched. The patient was taken to the recovery room in stable condition. Macroscopically, the hepatobiliary mass (the large necrotic mass in the RUQ, which was adherent to another mass in the liver, hepatic flexure, and omentum) was white-tan and was not well-encapsulated, measuring 9.0×7.0×4.5 cm, with firm consistency. On the cut surface, the mass was white-grey, gritty, with ill-defined border approaching free margin and infiltrating into the intestinal wall and omentum. The gall bladder wall was 1.2 cm thick, mainly in the hepatic area, and its cut surface showed areas of hepatic infiltration over the hepatic surface, with no gross mucosal lesion. The resected liver mass measured 13.5×8.5×5.5 cm. The cut surface showed white-grey, gritty, red focal areas of necrosis. Two pieces of posterior liver mass were also resected. Histopathologically (Figure 5A–5D), the hepatobiliary mass showed keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma with necrosis invading up to the submucosa of the colon wall. The gallbladder specimen showed keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma invading up to the mucosal surface. The liver masses also showed keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Cytopathology of the bile was positive for malignant cells, positive for squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 5.

(A–C) Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma involving. (A) Intestine, (B) gall bladder, (C) liver. (D) Characteristic squamous pearls of the hepatobiliary mass.

Since this is the first reported case of its type, there is no treatment protocol available. However, the initial decision was to treat the patient with combination therapy using weekly Cisplatin and radiotherapy. The patient received the first cycle of chemotherapy 6 weeks after surgery. A CT scan done 1 week after the second cycle showed progression of the disease, with development of new liver lesions. Combination therapy was stopped and the patient was offered palliative chemotherapy and hospice care. The patient is currently receiving home hospice services.

Discussion

Cholangiocarcinomas (CC) are malignant tumors that arise from the epithelium of the biliary system. Cholangiocarcinoma are broadly classified into intrahepatic and extrahepatic. Adenocarcinomas comprise the majority of malignant tumors of the biliary tree, with squamous cell carcinoma being very rare. Other rare histologic variants include adenosquamous carcinoma, undifferentiated tumors, neuroendocrine tumors, carcinosarcoma, and metastatic tumors. No case of IHCC with pure squamous cell histology was found in an extensive search of the literature. However, a few cases of IHCC with mixed adenosquamous histology [4–6] have been reported. There was also 1 case of primary basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the intrahepatic bile duct published recently [7]. Here, we report the first published case of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with pure squamous cell histology.

The diagnosis of CC is based on the combination of clinical presentation, imaging studies, tumor markers, and histology [8]. IHCC usually presents with vague symptoms like malaise, abdominal pain, and weight loss [9] but can present atypically with symptoms of bile duct obstruction, as in our case. Ultrasound is the initial diagnostic test. MRI with MRCP is the radiologic test of choice. ERCP is used to obtain brush cytology and/or biopsy of biliary ducts. The sensitivity of ERCP cytology is very low (30%) but is highly specific. The sensitivity of brush cytology increases (40–70%) if combined with biopsy. The most commonly used tumor markers are carcinoma antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The combination of these markers may improve the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of CC [8].

CA 19-9, a sialylated Lewis blood group antigen, is expressed by many tissues, including the pancreas and biliary tract epithelial cells. Very high levels (>1000 units/ml) represent advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma; however, it can be very high in obstructive jaundice mimicking pancreatic cancer. This could probably be from compression on the bile duct, resulting in its luminal accumulation and reflux into the circulation. Although CA 19-9 is a well-known tumor marker of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, its high levels should not be misinterpreted, especially in the presence of obstructive jaundice [10].

Several hypotheses have been proposed, but the precise mechanism of the development of squamous cell carcinoma in the bile ducts is not well understood. Cobot, who reported the first case of squamous cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic biliary duct in 1930, proposed that chronic inflammation induces squamous metaplasia of normal epithelium of the biliary tract [3]. This hypothesis is supported by various cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the biliary tract published in the literature. Our case is of pure squamous cell histology but there was no source of chronic inflammation.

Hepatic teratoma is a neoplasm containing cellular components from different germ cell layers, which can undergo malignant transformation to form squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous metaplasia leading to dysplasia and eventually squamous cell carcinoma can occur in cases of hepatolithiasis and benign hepatic cysts. In contrast, Nakajima et al. stressed that if the above hypothesis is true, the tumor should be composed purely of squamous cell elements instead of being a component [4]. Hepatic teratoma, hepatolithiasis, and hepatic cysts were not revealed on imaging studies in our case.

Hayafuchi and Kato hypothesized that an undifferentiated basal cell layer in cholecystitis related to gallstone could contribute to squamous cell carcinoma of the gallbladder [11]. Nakajima et al. reported that anaplastic carcinoma does retain the capacity to differentiate into squamous cell carcinoma [4]. Sewkani et al. reported that the probable etiology of squamous cell cancer is associated with ascariasis, liver fluke infestation, intrahepatic lithiasis, Caroli’s disease, choledochal cyst, choledocholithiasis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis [12]. None of the above were present in our case.

Kohno et al., in a study of adenosquamous carcinoma in cases of gallbladder cancer, suggested the transformation of adenocarcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma as one of the possible mechanisms of squamous cell carcinoma. They observed the transition from adenocarcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma and noticed that squamous cell carcinoma outgrew adenocarcinoma [3]. It has been demonstrated in an experimental animal model that squamous cell carcinoma is a result of histopathology alteration from adenocarcinoma with adenosquamous carcinoma as a transitional form [13]. In our case, there were no images showing metaplastic changes to squamous epithelium or transition from adenocarcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma. The histopathology images revealed keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma in all of the cells of the cancerous region.

Despite multiple hypotheses proposed, we cannot state the possible mechanism of squamous cell carcinoma in our case.

Nakajima et al. [4] compared 11 cases of cholangiocarcinoma containing a component of squamous cell carcinoma (CC-SCCC) with 82 cases of pure adenocarcinoma (CC-AC) for clinicopathological behavior. The mean survival rate of patients with CC-SCCC was 4±1.2 months verses 6.9±1.2 months in CC-AC. Mean tumor size was larger in CC-SCCC compared to CC-AC (10.2±2.2 cm and 8.3±1 cm respectively). CC-SCCC behaved more aggressively than CC-AC in terms of intrahepatic and metastatic spread. CC-SCCC had a 100% rate of intrahepatic metastasis compared to 55% of CC-AC. Based on this study, it can be concluded that CC-SCCC is more aggressive clinicopathologically, hence the poor prognosis. Based on the above study, it can be hypothesized that CC with pure SC histology can be very aggressive, but no data is available.

Conclusions

Squamous cell carcinoma of the biliary tree is very rare and the majority of tumors are adenocarcinomas. Here, we present the first published case report of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with pure squamous cell histology, and we have reviewed the previous reports. Although multiple hypotheses of squamous cell carcinoma of the hepatobiliary system have been proposed, the histogenesis of these tumors remains unknown. Based on previous reports, cholangiocarcinoma containing a squamous cell component have a poor prognosis due to aggressive behavior. It can be concluded that cholangiocarcinoma with pure squamous cell histology is very lethal, but no data is available because this is the first case reported.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Sumukh Patil (Attending Physician, Department Radiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai/Queens Hospital Center) helped with the radiological images.

Dr. Anatoly Leytin (Assistant Professor, Pathology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai/Elmhurst Hospital Center) provided the pathology images.

Deborah Goss, MLS (Director, Health Sciences Library, Queens Hospital Center) reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

Statement

There are no financial grants or funding sources to declare. There is no conflict of interest for the authors of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Cai JQ, Cai SW, Cong WM, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: a consensus from surgical specialists of China. Chinese Chapter of International hepato Pancreato Biliary Association; Liver Surgery Group, Surgical Branch of the Chinese Medical Association. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2014;34(4):469–75. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Njei B. Changing pattern of epidemiology in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60(3):1107–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.26958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamana I, Kawamoto S, Nagao S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the hilar bile duct. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011;5(2):463–70. doi: 10.1159/000331051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakajima T, Kondo Y. A clinicopathologic study of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma containing a component of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1990;65(6):1401–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900315)65:6<1401::aid-cncr2820650626>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochiai T, Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma with different morphologic and histologic components arising from the intrahepatic bile duct: report of a case. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43(9):663–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi H, Noh T, Ham BK, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney from cholangiocarcinoma. World J Mens Health. 2012;30(3):198–201. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2012.30.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkegaard J, Grunnet M, Hasselby JP. A fatal case of primary basaloid squamous cell carcinoma in the intrahepatic bile ducts. Case Rep Pathol. 2014;2014:410849. doi: 10.1155/2014/410849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel T. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3(1):33–42. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Beers BE. Diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10(2):87–93. doi: 10.1080/13651820801992716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adekolujo OS, Agu C, Shamar I, Trauber D. Advanced gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting with obstructive jaundice and very high CA 19-9 level mimicking pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12029-015-9728-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayafuchi N, Kato N. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenoacanthoma of biliary tracts (gall bladder and choledochus) Kyushu Kohnenbyo Nenpoh. 1975;3:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sewkani A, Kapoor S, Sharma S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the distal common bile duct. JOP. 2005;6(2):162–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iemura A, Yano H, Mizoguchi A, Kojiro M. A cholangiocellular carcinoma nude mouse strain showing histologic alteration from adenocarcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1992;70(2):415–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920715)70:2<415::aid-cncr2820700208>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]