Small amounts of super-antigens from catheter-associated S. aureus elicit systemic inflammation in the absence of bacteremia in mice.

Keywords: HLA class II, transgenic mice, cytokines, T lymphocytes, immunopathology

Abstract

SAgs, produced by Staphylococcus aureus, play a major role in the pathogenesis of invasive staphylococcal diseases by inducing potent activation of the immune system. However, the role of SAgs, produced by S. aureus, associated with indwelling devices or tissues, are not known. Given the prevalence of device-associated infection with toxigenic S. aureus in clinical settings and the potency of SAgs, we hypothesized that continuous exposure to SAgs produced by catheter-associated S. aureus could have systemic consequences. To investigate these effects, we established a murine in vivo catheter colonization model. One centimeter long intravenous catheters were colonized with a clinical S. aureus isolate producing SAgs or isogenic S. aureus strains, capable or incapable of producing SAg. Catheters were subcutaneously implanted in age-matched HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice lacking MHC class II molecules and euthanized 7 d later. There was no evidence of systemic infection. However, in HLA-DR3 transgenic mice, which respond robustly to SSAgs, the SSAg-producing, but not the nonproducing strains, caused a transient increase in serum cytokine levels and a protracted expansion of splenic CD4+ T cells expressing SSAg-reactive TCR Vβ8. Lungs, livers, and kidneys from these mice showed infiltration with CD4+ and CD11b+ cells. These findings were absent in B6 and AEo mice, which are known to respond poorly to SSAgs. Overall, our novel findings suggest that systemic immune activation elicited by SAgs, produced by S. aureus colonizing foreign bodies, could have clinical consequences in humans.

Introduction

Approximately 15 million central vascular catheter days are accrued in the intensive care units each year in the United States [1]. Inclusion of all types of catheters, both in intensive and nonintensive care settings, raises the number of patients with any type of catheter to several millions. Infection is a common complication associated with catheters, and Staphylococcus aureus is the second leading cause of such infections [2]. S. aureus can readily colonize and tenaciously grow as biofilms on catheters [3–5]. Catheter colonization may be asymptomatic or may result in catheter-associated bloodstream infection and/or local findings of infection.

As it does in the planktonic state, S. aureus in the biofilm state can produce several exotoxins [6, 7]. These exotoxins are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of infections caused by planktonically growing S. aureus [8, 9]. However, the role of staphylococcal exotoxins in biofilm-associated infections and more specifically, in colonization of foreign bodies is only beginning to emerge [6, 7]. For example, recent studies have shown that phenol-soluble modulins, α and β toxins, play roles in S. aureus biofilm infections [10–13]. The contribution of SSAgs, another family of staphylococcal exotoxins, to the pathogenesis of S. aureus colonizing catheters has not been investigated in detail.

SSAgs are powerful activators of T lymphocytes and other cells of the immune system [14]. Acute exposure to large amounts of SSAgs produced during infections, such as pneumonia, sepsis, or skin and soft tissue infections, causes a rapid and robust activation of the immune system, resulting in a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, followed by failure of multiple organs, which can be fatal if not acted upon in a timely manner [14]. S. aureus biofilms can also produce SSAgs [15, 16], and this may contribute to the pathogenesis of catheter-associated infection in vivo or have clinical consequences for catheter colonization. However, to our knowledge, this has not been investigated. Therefore, we established a murine model of catheter-associated staphylococcal infection by use of a SSAg-producing clinical isolate, as well as isogenic strains of S. aureus, producing or not producing SSAgs. With the use of 3 different strains of mice that vary in their responsiveness to SSAgs, we demonstrate for the first time that even when S. aureus is localized to a catheter, the small amounts of SSAgs that they elaborate can elicit a systemic inflammatory response affecting multiple organs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

HLA-DR3 transgenic mice expressing HLA-DRA1*0101 and HLA-DRB1*0301 transgenes on the complete mouse MHC class II-deficient background have been described [17–20]. B6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and AE° (endogenous as well as transgenic) were also used. HLA-DR3 mice respond more robustly to SSAgs than B6 mice, whereas AE° mice cannot respond to SSAgs as a result of the absence of MHC class II molecules [21]. All of the experiments were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bacterial isolates

IDRL-7971 is a methicillin-susceptible S. aureus clinical isolate producing SEA and SEB [16, 22]. The S. aureus strain RN6734 contains the intact cloned seb pRN5543::seb (pRN7114) and produces SEB (referred to as SEB+SA). RN6734 contains a derivative with a large 3′ deletion in seb, pRN5543::seb(b.2) (pRN7116), and does not produce SEB (referred to as SEB−SA). These 2 strains were a generous gift from Richard Novick (New York University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA) [23]. The SEB+SA and SEB−SA strains were grown in TSB, supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 µg/ml).

Preparation of culture supernatants from S. aureus colonizing devices

S. aureus colonies were pre-established on 1 cm diameter Teflon discs [16]. In brief, discs were incubated with a starting inoculum of 106 CFU/ml in TSB. After 24 hours, the discs were rinsed in saline to remove planktonic cells, placed into 2 ml TSB containing vancomycin (4 μg/ml), and incubated for an additional 24 hours. The fluid surrounding the discs was collected, spun, and filtered (MILLEX GP; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and the supernatants were stored at −80°C. SEA/B/C/D/E , in the culture supernatants, were tested by use of the TECRA Staph Enterotoxins ID kit (3M, St. Paul, MN, USA) and by splenocyte proliferation bioassay.

Splenocyte proliferation assay

Naive splenocytes were cultured in HEPES-buffered RPMI 1640 medium, containing 5% FCS, serum supplement, streptomycin, and penicillin in 100 μl vol 106 cells/ml in 96-well, round-bottomed, tissue-culture plates. Bacterial supernatants were added at 1–256 dilutions and incubated at 37°C. After 48 hours, 1 μg tritiated [3H]thymidine was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 18 hours. The extent of proliferation was determined by measuring incorporated radioactivity [16, 22].

Preparation of catheter-associated staphylococci and scanning electron microscopy

Frozen S. aureus stocks were streaked onto sheep blood agar plates (for IDRL-7971) or Muller Hinton agar with 20 µg/ml chloramphenicol (for SEB+SA and SEB−SA) and incubated at 37°C. The following morning, 5 colonies were inoculated into 10 ml TSB and incubated at 37°C for 6–8 hours on an orbital shaker until reaching a turbidity of ∼108 cfu/ml. One centimeter pieces of catheters (14 gauge Abbocath-T; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were cut by use of a sterile surgical scalpel and placed individually into 990 μl sterile TSB. Subsequently, 10 μl of 1/10 diluted bacterial broth was inoculated into TSB containing the catheters and incubated overnight on an orbital shaker at 37°C.

For scanning electron microscopy, catheter segments were longitudinally bisected and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin with postfixation in 2% paraformaldehyde with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and secondary fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide, as described earlier [24]. Samples were viewed by use of a Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA), operated at 25 kV.

Transwell culture system to determine IL-2 induction by catheter-associated staphylococci

Single-cell suspensions of naïve splenocytes were prepared as above. One milliliter of cells (106 cells/ml) was added to the outside chambers of each well in a 12-well transwell plate (Corning, Tewksbury, MA, USA), whereas 500 μl serum-supplemented RPMI 1640 medium was added to the inside chamber. One catheter (control or with staphylococci) was placed onto the membrane of the inside chambers (inserts) of each transwell. The pore size of the insert prevents direct exposure of splenocytes to bacteria. Plates were incubated at 37°C. After 48 hours, medium from outside chambers was aspirated. A small aliquot was inoculated into TSB broth to check for sterility. The amount of IL-2 in the culture supernatants was quantified by use of a sandwich ELISA following the manufacturer’s protocol (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA).

Implantation of catheters in mice

Catheters were implanted subcutaneously on the back of age-matched recipient mice. In brief, mice were anesthetized by use of ketamine and xylazine. Hair was removed by use of clippers and the surgical site disinfected with a Betadine sponge. A small skin incision was made by use of a sterile scalpel, and a subcutaneous pocket was created into which the catheters were inserted gently. Before implantation, the catheters were dipped thrice in a Petri dish containing sterile saline to remove nonadherent bacteria. The skin wound was closed by use of surgical staples. Mice and surgical wound sites were monitored twice daily. Mice were euthanized 7 d later.

Determination of bacterial quantity of catheters, blood, and organs

Aseptically removed catheters were placed into 1 ml sterile saline, vortexed for 30 s, sonicated for 5 min (frequency, 40 ± 2 kHz; power density, 0.22 ± 0.04 W/cm2; Zenith Ultrasonic, Norwood, NJ, USA), and vortexed again for 30 s. The sonicate fluid was quantitatively cultured and reported as log10 cfu/cm2. Organs collected aseptically were placed into a sterile stomacher bag with 1 ml TSB, homogenized for 120 s, and vortexed an additional 30 s. Quantitative cultures were performed and results reported as colony forming units per gram tissue. Blood (100 µl), collected via cardiac puncture, was inoculated onto sheep blood agar and into thioglycollate broth and incubated for up to 5 d.

Flow cytometry and determination of serum cytokine/chemokine concentrations

RBC-depleted splenocytes were stained with the following fluorochrome-labeled antibodies: CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), TCR Vβ6 (RR4-7), TCR Vβ8 (F23.1), B220 (RA3-6B2), and Mac-1 (M 1/70; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed by use of FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). Serum cytokine/chemokine concentrations were determined in duplicates by use of a multiplex bead assay, per the manufacturer’s protocol, and by use of their software and hardware (Bio-Plex; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining

Formalin-fixed livers, lungs, and kidneys were embedded in paraffin. Thin sections were stained with H&E for histopathologic evaluation. Tissues were also collected in optimal cutting compound (Tissue-Tek O.C.T.; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and stored at −80°C. Cryosections were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, mounted by use of the SlowFade Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and analyzed by use of an Olympus AX70 research microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons of means between groups were made by use of a Student’s t-test, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by use of SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism, version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Where indicated, statistical significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test by use of the GraphPad Prism program.

RESULTS

A clinical isolate of S. aureus readily colonizes catheters and produces biologically active SAgs when grown in vitro

Colonization of catheters by S. aureus IDRL-7971 on the catheter was evident when tested by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 1A). Filtered supernatants from catheters colonized with IDRL-7971 contained SEA and SEB when tested by specific immunoassays (Fig. 1B). In bioassays, supernatants from catheters colonized with IDRL-7971 induced very little proliferation in splenocytes from AEo mice (Fig. 1C). However, splenocytes from HLA-DR3 transgenic mice proliferated more robustly than did splenocytes from B6 mice (Fig. 1C). Supernatants from AEo splenocytes coincubated with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters in a transwell culture system contained very little IL-2. However, HLA-DR3 supernatants contained more IL-2 than B6 supernatants in the cocultures (Fig. 1D). Higher proliferation and elevation of IL-2 production in splenocytes from HLA-DR3 mice (which respond robustly to SSAgs) but not in B6 mice (which respond poorly to SSAg) or AEo mice (which cannot present SSAgs) strongly supported the presence of SSAgs in culture supernatants from catheters colonized with S. aureus.

Figure 1. Efficient colonization of catheters and production of SAg by the clinical isolate S. aureus IDRL-7971.

(A) One centimeter segments of intravenous catheters were incubated with IDRL-7971, as described in Materials and Methods. The next day, catheter segments were gently rinsed in saline, longitudinally bisected, fixed in neutral buffered formalin, and processed for scanning electron microscopy. A representative image is shown. (B) Filtered culture supernatants from catheters containing IDRL-7971 were tested for the presence of SEA/B/C/D/E by the TECRA Staph Enterotoxins ID kit (3M). PC and NC, Absorbance values corresponding to positive and negative controls, respectively, provided with the kit. Representative data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (C) Splenocytes from HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice were cultured with TSB alone or with supernatants from IDRL-7971 catheter cultures. Splenocyte proliferation was determined by a thymidine incorporation assay. Representative data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (D) Splenocytes from HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice were cultured with catheters colonized with IDRL-7971 in a transwell culture plate. Supernatants were harvested, filtered, serially diluted, and tested for the presence of IL-2 by ELISA. Representative data from 2 independent experiments are shown.

Implantation of catheters colonized with toxigenic S. aureus does not cause bacteremia

HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice were implanted with catheters harboring S. aureus IDRL-7971. All mice were lethargic for the first few hours following surgery (recovery phase), irrespective of whether they received control or colonized catheters. HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters continued to show reduced activity for 1–2 d and also exhibited ocular discharge, shivering, and ruffled fur. However, by day 3, they recovered and resumed normal activity. On the other hand, B6 and AEo mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters had no changes in activity, ocular discharge, shivering, or ruffled fur. There were no signs of infection at the site of catheter implantation in any of the mice.

Seven days after surgery, animals were euthanized and catheters harvested and quantitatively cultured. No pus or other indication of infection was visible around the catheters in any of the mice. The bacterial quantity on the catheters was similar pre- and postimplantation (6.32 ± 0.19 and 6.52 ± 0.19 log10 cfu/cm2, mean ± se, respectively), and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.613). The colony counts were also comparable among different recipient groups (data not shown). Blood and organ cultures were negative from all mice, supporting the absence of systemic infection.

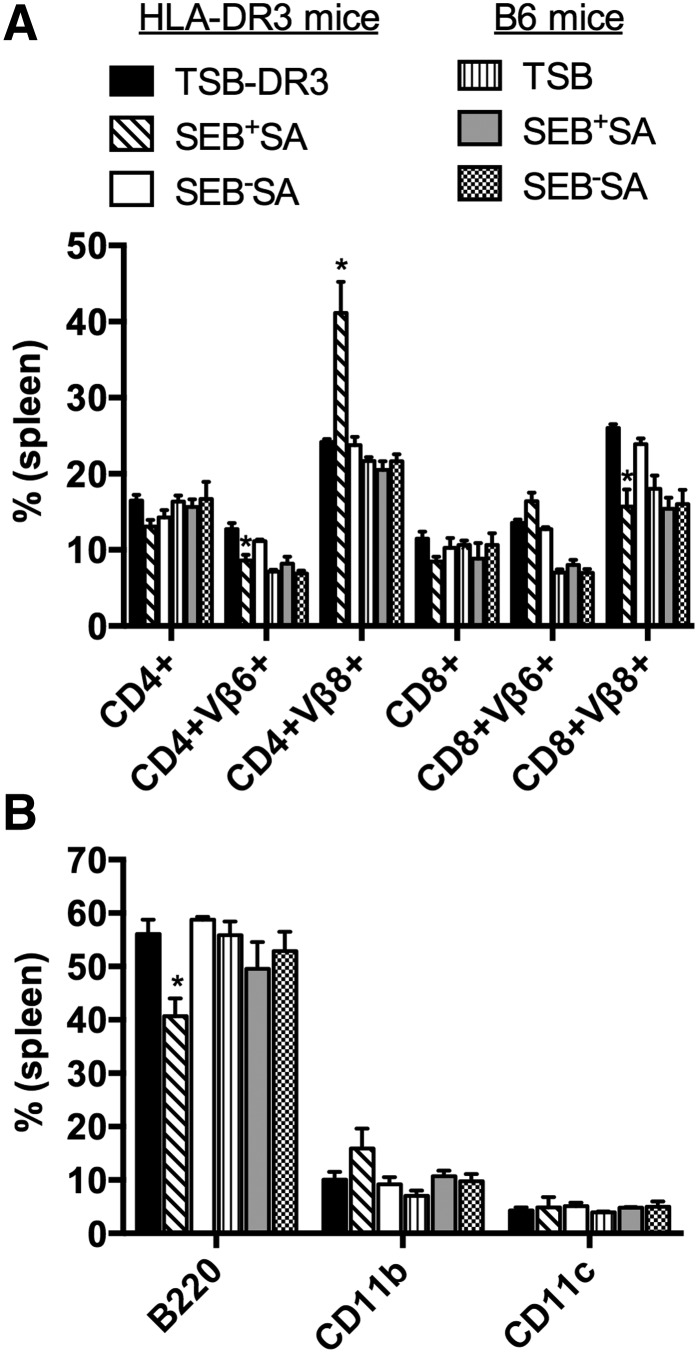

Catheter-associated S. aureus causes expansion of T cells bearing certain TCR Vβ families suggestive of SSAg involvement

SSAgs activate of T cells bearing specific TCR Vβ families, and SEB, produced by IDRL-7971, has specificity for TCR Vβ8. To determine the functional consequence of SSAg, elaborated by catheters colonized with SSAg-producing S. aureus in vivo, we studied the distribution of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing SEB-specific TCR (Vβ8) and a nonspecific control TCR (Vβ6). To rule out nonspecific activation of the immune system, we also enumerated the distribution of B cells, macrophages, and DCs in the spleens from all 3 strains of mice. Compared with mice implanted with control catheters, there was a significant increase in the percentage of SEB-reactive TCR Vβ8-bearing CD4+ T cells and a corresponding decrease in the percentage of TCR Vβ6-bearing CD4+ T cells in the spleens of HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971 catheters (Fig. 2A). However, there was a significant reduction in the percentage of CD8+ T cells bearing TCR Vβ8 and a corresponding increase in TCR Vβ6-bearing CD8+ T cells. When converted to absolute numbers, the SEB-reactive, TCR Vβ8-bearing CD4+ T cell numbers were higher in HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971 catheters compared with those implanted with control catheters (Fig. 2B). Whereas the total number of SEB-reactive, TCR Vβ8-bearing CD8+ T cells was trended to be lower in HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971 catheters, this did not attain statistical significance.

Figure 2. Subcutaneous implantation of catheters colonized with SAgs-producing S. aureus IDRL-7971 causes expansion of SAg-reactive T cells.

Control catheters or catheters precolonized with IDRL-7971 were implanted subcutaneously at the backs of HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice. Seven days later, spleens were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing SEB-reactive TCR Vβ8 and the control TCR Vβ6 in the spleens. (B) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing SEB-reactive TCR Vβ8 and the control TCR Vβ6 in spleens of HLA-DR3 transgenic mice implanted with control or IDRL-7971 catheters. (C) Percentages of B220+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ cells in the spleens. Each bar represents mean ± se from 4 to 8 mice. *P < 0.05 compared with corresponding TSB group.

There were no significant variations in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell expressing TCR Vβ8 or TCR Vβ6 in B6 mice implanted with IDRL-7971 catheters (Fig. 2A and B). As AEo mice lack MHC class II molecules, they harbor significantly reduced numbers of CD4+ but normal numbers of CD8+ T cells. As expected, implantation of IDRL-7971-colonized catheters caused no changes in TCR Vβ8-bearing T cells in AEo mice. There were no significant differences in the percentage or absolute numbers of B220+ (predominantly B cells), CD11b+ (predominantly macrophages), or CD11c+ (predominantly DC) cells between mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized or control catheters in any mouse strain (Fig. 2C). Specific changes in T cells bearing SSAg-reactive TCR Vβ8 in HLA-DR3 mice with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters but not in B6 mice (which respond poorly to SSAg) or AEo mice (which cannot present SSAgs) indicated the production of SSAgs by catheters colonized with S. aureus in vivo.

Catheter-associated S. aureus causes infiltration of major organs with inflammatory cells

Microscopic evaluation of tissues from B6 mice implanted with control TSB catheters, as well as IDRL-7971-colonized catheters, appeared normal (Fig. 3). However, whereas tissues from HLA-DR3 mice implanted with control catheters appeared normal, lungs, livers, and kidneys from HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters showed extensive inflammation (Fig. 3). Lung alveoli were collapsed as a result of extensive infiltration, which in the liver, was mostly perivascular, whereas in the kidneys, there was perivascular and periglomerular inflammatory cell infiltration.

Figure 3. Subcutaneous implantation of catheters colonized with SAg-producing S. aureus IDRL-7971 causes infiltration of vital organs with inflammatory cells.

HLA-DR3 and B6 mice were implanted subcutaneously with control catheters or catheters precolonized with IDRL-7971. Seven days later, lungs, livers, and kidneys were collected, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Representative images are shown. Insets within each panel show higher magnification. Representative images are shown.

Liver sections from B6 mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters stained positively for occasional macrophages (CD11b+) but were negative for CD4+, CD8+, B220+, or CD11c+ cells (Fig. 4, and additional data not shown). Liver sections from HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters stained for CD4+ as well as CD11b+ cells, whereas controls did not. We did not detect any staining with anti-CD8, anti-B220+, or anti-CD11c antibodies (Fig. 4, and additional data not shown). The differential inflammatory response between B6 and HLA-DR3 mice further supported the involvement of SSAg.

Figure 4. Subcutaneous implantation of catheters colonized with SAg-producing clinical S. aureus IDRL-7971 causes infiltration with CD4+ T cells and CD11b+ cells.

HLA-DR3 and B6 mice were implanted subcutaneously with control catheters or catheters precolonized with IDRL-7971. Livers collected 7 d later were cryosectioned and stained with FITC-conjugated CD4 (A) and CD11b (B) antibodies. Representative images are shown. (Left) DAPI stain of the nuclei; (middle) FITC stain; (right) DAPI-FITC overlay. Representative images are shown.

Systemic inflammatory reaction elicited by S. aureus colonizing catheters is mediated by SSAgs

To establish further that only SSAgs but not other staphylococcal exotoxins or molecules were responsible for the above results, we studied isogenic SEB+SA and SEB−SA strains in our model. There were no differences in the abilities of these 2 strains to colonize catheters, as examined by scanning electron microscopy (data not shown). Enzyme immunoassays confirmed that SEB+SA produced only SEB; the SEB−SA strain did not produce any SSAgs (Fig. 5A). As expected, only supernatants from the SEB+SA-colonizing the catheters induced proliferation in splenocytes from HLA-DR3 mice but not B6 and AEo mice (Fig. 5B). Only the SEB+SA strain induced IL-2 production from HLA-DR3 splenocytes in the transwell culture system (Fig. 5C), thus confirming that SEB+SA colonizing the catheters produce biologically active SEB, which stimulates T cells to produce IL-2.

Figure 5. SAg toxin profile and SAg production by experimental S. aureus isolates, SEB+SA and SEB−SA.

(A) Filtered culture supernatants of SEB+SA and SEB−SA were tested for the presence of SEA/B/C/D/E by the TECRA Staph Enterotoxins ID kit (3M). Representative data from 2 independent experiments are shown. (B) Splenocytes from HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice were cultured with TSB alone or with supernatants from SEB+SA and SEB−SA cultures. The extent of splenocyte proliferation was determined by thymidine incorporation assay. Representative data from several independent experiments are shown. (C) Splenocytes from HLA-DR3, B6, and AEo mice were cultured with catheters colonized with SEB+SA and SEB−SA in a transwell culture plate. Supernatants were harvested, filtered, and tested for the presence of IL-2 by ELISA. Representative data from 2 independent experiments are shown.

HLA-DR3 and B6 mice, subcutaneously implanted with SEB+SA and SEB−SA catheters, were euthanized 7 d later. The preimplantation colony counts (mean ± se) were 6.53 ± 0.24 and 6.39 ± 0.22 log10 cfu/cm2 for SEB+SA and SEB−SA, respectively. There was no difference in postimplantation colony counts (mean ± se), which were 6.29 ± 0.33 and 6.69 ± 0.08 log10 cfu/cm2 for SEB+SA and SEB−SA, respectively. The colony counts were also similar between HLA-DR3 and B6 mice. No findings of infection were present at the site of implantation or around the catheters in any of the mice.

The spleens from HLA-DR3 mice implanted with the SEB+SA but not SEB−SA catheters had more TCR Vβ8-bearing CD4+ T cells and fewer TCR Vβ8-bearing CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6). Spleens from B6 mice implanted with catheters colonized by SEB+SA showed no changes. There were no changes in B220+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ splenocyte subsets in any mice, further implying the role for SSAgs (Fig. 6B). Neither blood nor organ homogenates from any of these mice grew S. aureus, suggesting the absence of systemic S. aureus infection.

Figure 6. Subcutaneous implantation of catheters colonized with SEB+SA and SEB−SA causes expansion of SAg-reactive T cells.

Control catheters or catheters precolonized with SEB+SA and SEB-SA were implanted subcutaneously into HLA-DR3 and B6 mice. Seven days later, spleens were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing SEB-reactive TCR Vβ8 and the control TCR Vβ6 in spleens. (B) Absolute numbers of B220+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ cells in the spleens. Each bar represents mean ± se from 4 to 8 mice. *P < 0.05 by use of the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

The lungs, livers, and kidneys from HLA-DR3 mice implanted with control catheters, as well as catheters colonized with SEB−SA, appeared normal (Fig. 7). However, organs from HLA-DR3 mice, implanted with catheters colonized with SEB+SA, showed inflammatory changes. Organs from B6 mice with SEB+SA-colonized catheters showed no inflammation, similar to mice with control TSB catheters or SEB−SA-colonized catheters (Fig. 7). Immunostaining of frozen sections of livers and kidneys from HLA-DR3 mice with catheters, colonized with SEB+SA, showed infiltration with CD4+ T cells and CD11b+ cells with no CD8+ or CD11c+ cells (Fig. 8). Cryosections from HLA-DR3, implanted with catheters colonized by SEB−SA, showed no infiltration (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that catheter-associated S. aureus produce functional SSAgs, which cause activation of T cells in an HLA-DR3-dependent manner, resulting in a systemic inflammatory response.

Figure 7. Subcutaneous implantation of catheters colonized with S. aureus causes infiltration of vital organs with inflammatory cells in a SAg-dependent manner.

(A) B6 and (B) HLA-DR3 transgenic mice were implanted subcutaneously with control catheters or catheters precolonized with SEB+SA or SEB−SA. Seven days later, lungs, livers, and kidneys were collected, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Insets within each panel show higher magnification. Representative images are shown.

Figure 8. Subcutaneous implantation of catheters colonized with SEB+SA causes infiltration of vital organs with CD4+ T cells and CD11b+ cells.

HLA-DR3 were implanted subcutaneously with control catheters or catheters precolonized with SEB+SA. Kidneys and livers, collected 7 d later, were cryosectioned and stained with FITC-conjugated CD4, CD8, CD11b, and CD11c antibodies. Representative images are shown. (Top) Kidney; (Bottom) liver.

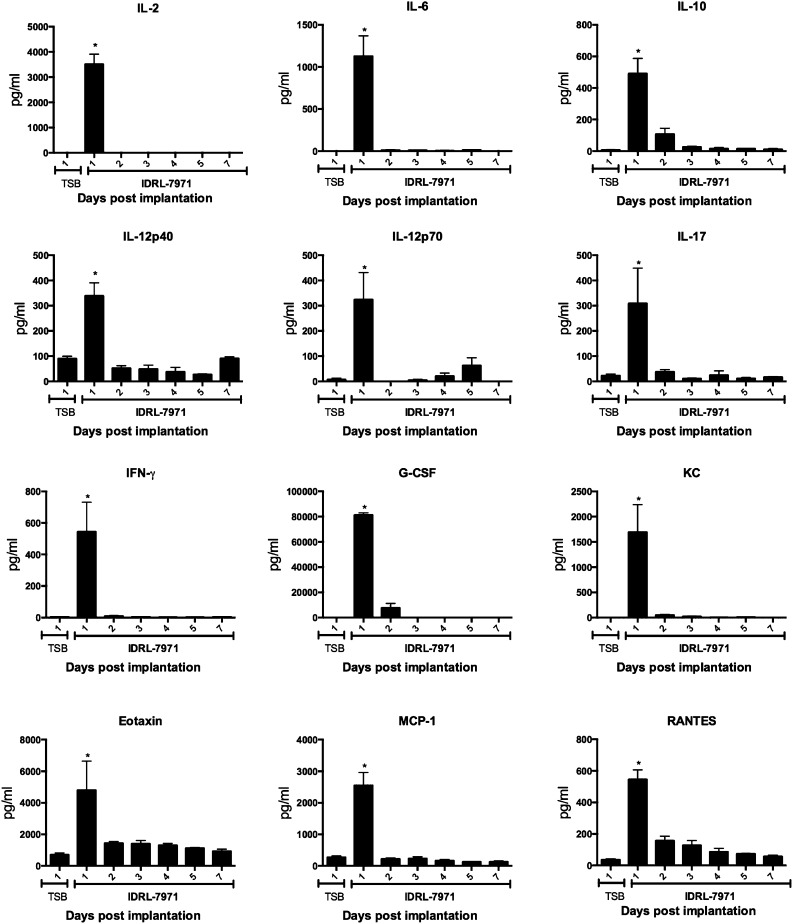

Early elevation in systemic levels of cytokines/chemokines in mice implanted with catheters colonized with toxigenic S. aureus

SEB, produced by IDRL-7971, as well as SEB+SA, causes activation and proliferation of CD4+ as well as CD8+ T cells bearing TCR Vβ8 [25, 26]. However, in our catheter-associated infection model, we observed consistently that the CD4+ TCR Vβ8+ T cells in the spleens proliferated and expanded, whereas the CD8+ TCR Vβ8+ T cells were reduced in numbers. To understand this phenomenon better and to study the kinetics of immune activation over the duration of the catheter implantation, we performed a temporal study. As Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee’s guidelines forbid repeat bleeding from the same animals, groups of 4 HLA-DR3 mice implanted with IDRL-7971-colonized catheters were euthanized daily for 1 week. Sera were collected for multiplex cytokine assays and spleens for flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 9, there was a spike in serum levels of most cytokines and chemokines tested on day 1, which quickly tapered off to baseline levels by day 2, remaining at baseline levels thereafter. In the spleens, whereas CD4+ as well as CD8+ T cells bearing TCR Vβ8 expanded from days 2–4, TCR Vβ8-bearing CD4+ T cells persisted at elevated numbers, whereas the TCR Vβ8-bearing CD8+ T cells began to decline, reaching lowest numbers by day 7 (Fig. 10). This suggested a differential response between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to chronic stimulation with SSAg. The numbers of bacteria on the catheters remained stable over the study period (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 9. Temporal kinetics of cytokine/chemokine production in HLA-DR3 mice implanted with catheters colonized with S. aureus.

Age-matched HLA-DR3 mice were implanted subcutaneously with control catheters or catheters precolonized with IDRL-7971. Mice were euthanized daily for 7 d, and sera were collected immediately after euthanasia. Serum levels of indicated cytokines/chemokines were determined by multiplex assay. Each bar represents mean ± se from 4 mice. *P < 0.05 by use of Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. KC, keratinocyte-derived chemokine.

Figure 10. Temporal kinetics of expansion of SAg-reactive T cells in HLA-DR3 mice implanted with catheters colonized with S. aureus.

Age-matched HLA-DR3 mice were implanted subcutaneously with control catheters or catheters precolonized with IDRL-7971. Mice were euthanized daily for 7 d, spleens were collected immediately after euthanasia, and distribution of indicated T cell subsets was determined by flow cytometry. Each bar represents mean ± se from 4 mice. POD, postoperation day. *P < 0.05 compared with corresponding TSB control group.

DISCUSSION

Exotoxins (such as SSAgs, Panton-Valentine leukocidin, and cytolytic toxins) and other virulence-determining factors (such as phenol-soluble modulins) play major roles in the pathogenesis of invasive diseases caused by S. aureus [8, 14, 27]. However, the impact of these staphylococcal molecules, particularly the SSAgs, in the pathogenesis of S. aureus colonizing foreign bodies is not fully understood. Given that more than two-thirds of bacterial infections involve biofilms [28], the role of exotoxin production by biofilms needs to be elucidated so that novel therapies can be instituted against them. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the role of SSAgs in the pathogenesis of catheter-associated staphylococcal infection, a widespread problem in the hospital settings. Our experiments demonstrate for the first time that S. aureus, even when localized to a catheter, is capable of eliciting a systemic inflammatory response through SSAg production in the absence of systemic infection.

SSAgs are a distinctive family of exotoxins capable of activating the T cells [14]. They cause T cell activation in a unique manner. SSAgs first bind directly to MHC class II molecules outside of the peptide-binding groove without undergoing any processing. Subsequently, they interact with certain TCR Vβ gene families expressed by CD4+ as well as CD8+ T cells and cross link the TCR, resulting in their activation. Therefore, MHC class II molecules are required for T cell activation by SSAgs. Among the MHC class II molecules, SSAgs bind with higher affinity to human MHC (HLA) class II molecules than to murine MHC class II molecules. As a result, HLA class II transgenic mice mount a superior response to SSAgs than B6 mice [21, 25, 29]. Therefore, increased proliferation and production of IL-2, a T cell-derived cytokine, by HLA-DR3 compared with B6 splenocytes in the in vitro studies indicate that SSAgs are produced by S. aureus colonizing the catheters. Poor proliferative responses and lack of IL-2 production in splenocytes from AEo mice that lack any MHC class II molecules established that SSAgs were likely responsible for this effect. Our experiments that use isogenic strains of S. aureus producing or lacking SEB validated this conclusion. Only the supernatants from catheters colonized with SEB-producing S. aureus induced proliferation and IL-2 production. Overall, our in vitro studies confirmed the production of SSAgs by catheter-associated S. aureus.

SSAgs, as discussed above, cause activation of T cells expressing specific TCR Vβ families. Therefore, expansion of T cells reactive to SEB (TCR Vβ8) only in HLA-DR3 transgenic mice that received catheters, colonized with SSAg-producing S. aureus and absence of these responses in B6 or AEo mice, corroborates production of SSAgs by S. aureus colonizing the catheters in vivo. Interestingly, none of the classic signs of acute SSAg toxicity or mortality were present in HLA-DR3 mice implanted with catheters colonized with SSAg-producing S. aureus. Even the systemic levels of cytokines/chemokines in these mice were much lower compared with HLA-DR3 transgenic mice with acute lethal SSAg-induced toxic shock [21, 25]. We hypothesize that this is a result of the continued production of small amounts of SSAgs by the catheter-associated S. aureus. Given that the bacterial load in the catheters remained at low levels without any significant change throughout the study, we postulate that the organisms in their stationary phase produced a continuous but small amount of SSAgs. The inability to culture viable bacteria from blood as well as other organs suggests that the organisms remained localized to the catheter. Nonetheless, thes SSAgs were able to activate the T cells and other cells of the immune system by the process described earlier, resulting in systemic immunopathology. As blood and organ cultures were performed only on day 7, it is possible that some organisms had been dislodged from the catheters before the time of culturing, at which point, they had been cleared/controlled by the host’s immune system. As the effects of SSAg were still apparent on day 7, at which point, blood and organ cultures were negative, we believe that the catheters colonized with S. aureus were the source of SSAg.

The striking similarity between the findings of the current study and our previous investigation, in which we delivered purified SSAgs over 7 d by use of miniosmotic pumps, also placed subcutaneously, further implicates SSAgs as the cause of the observed multiorgan inflammation [30]. Another important observation from this study is the impact of SSAgs on the growth of colonies in catheters. Recent studies have shown that α and β toxins play important roles in the formation of biofilms by S. aureus, as mutant strains lacking these toxins failed to form biofilms [10–12]. However, our study revealed that SSAgs do not have an effect on colonization and growth on catheters, as the isogenic strain lacking SSAgs also colonized and grew efficiently on catheters. Moreover, the bacterial colony counts associated with the catheters in vivo did not vary significantly throughout the experimental time period. Similar observations have been made previously, indicating an extremely slow growth of staphylococci associated with devices in vivo [31, 32]. Further studies are underway to delineate the effects of SSAgs on growth on indwelling devices and antibiofilm immune response.

Acute exposure to SSAgs causes activation and expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing certain TCR Vβ families, followed by their deletion. However, in our study, the reasons why chronic exposure to SSAgs caused continued expansion of CD4+ T cells bearing TCR Vβ8, but activation followed by deletion of CD8+ T cells bearing TCR Vβ8 are unclear. However, this phenomenon has been described previously [33]. While tracking the responses of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing the same high-affinity TCR (same peptide-MHC specificity), Engels et al. [33] showed that whereas CD4+ T cells expressing a high-affinity TCR underwent expansion and persisted in vivo for months, CD8+ T cells expressing the same high-affinity TCR underwent deletion. Given the robustness with which SSAgs activate T cells, we believe that a similar phenomenon occurs with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing TCR Vβ8 in our model.

Activation of T cells during persistent bacterial infections, such as biofilms, has been demonstrated in humans [34]. We describe here a novel finding that SSAgs produced by S. aureus colonizing, indwelling catheters can cause T cell activation and elicit a systemic inflammatory response in the absence of systemic infection. As humans are more susceptible to the immune-stimulating effects of SSAgs, the clinical implications of our findings in humans could be significant and warrant exploration.

AUTHORSHIP

J.-W.G., K.E.G.-Q., and M.J.K. executed the experiments, collected and interpreted data, and prepared the manuscript. A.T. and S.R.K. executed the experiments and collected and interpreted the data. V.R.C. and C.S.D. generated the hypothesis and design of experiments. R.P. generated the hypothesis, designed the experiments, and prepared the manuscript. G.R. generated the hypothesis, designed and executed the experiments, collected and interpreted data, and prepared and submitted the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants AI101172 (to G.R.) and AI68741 (to G.R. and C.S.D.). The authors thank Julie Hanson and her crew for excellent mice husbandry and Michelle Smart for characterizing the transgenic mice.

Glossary

- AE°

mice lacking all MHC class II

- B6

C57Bl/6

- DC

dendritic cell

- SAg

superantigen

- SEA/B/C/D/E

staphylococcal enterotoxin A/B/C/D/E

- SEB−SA

isogenic S. aureus not producing staphylococcal enterotoxin B

- SEB+SA

S. aureus producing staphylococcal enterotoxin B

- SSAg

staphylococcal superantigen

- TSB

trypticase soy broth

- Vβ

variable region β

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Grady N. P., Alexander M., Burns L. A., Dellinger E. P., Garland J., Heard S. O., Lipsett P. A., Masur H., Mermel L. A., Pearson M. L., Raad I. I., Randolph A. G., Rupp M. E., Saint S.; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (2011) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am. J. Infect. Control 39 (4 Suppl 1) S1–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donlan R. M. (2001) Biofilms and device-associated infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 277–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidron A. I., Edwards J. R., Patel J., Horan T. C., Sievert D. M., Pollock D. A., Fridkin S. K.; National Healthcare Safety Network Team; Participating National Healthcare Safety Network Facilities (2008) NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29, 996–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady R. A., Leid J. G., Calhoun J. H., Costerton J. W., Shirtliff M. E. (2008) Osteomyelitis and the role of biofilms in chronic infection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 52, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archer N. K., Mazaitis M. J., Costerton J. W., Leid J. G., Powers M. E., Shirtliff M. E. (2011) Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: properties, regulation, and roles in human disease. Virulence 2, 445–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yarwood J. M., Bartels D. J., Volper E. M., Greenberg E. P. (2004) Quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186, 1838–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherr T. D., Roux C. M., Hanke M. L., Angle A., Dunman P. M., Kielian T. (2013) Global transcriptome analysis of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in response to innate immune cells. Infect. Immun. 81, 4363–4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto M. (2014) Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 17, 32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster T. J., Geoghegan J. A., Ganesh V. K., Höök M. (2014) Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 49–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caiazza N. C., O’Toole G. A. (2003) Alpha-toxin is required for biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3214–3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson M. J., Lin Y-C., Gillman A. N., Parks P. J., Schlievert P. M., Peterson M. (2012) Alpha-Toxin promotes mucosal biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huseby M. J., Kruse A. C., Digre J., Kohler P. L., Vocke J. A., Mann E. E., Bayles K. W., Bohach G. A., Schlievert P. M., Ohlendorf D. H., Earhart C. A. (2010) Beta Toxin catalyzes formation of nucleoprotein matrix in staphylococcal biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14407–14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Periasamy S., Joo H.-S., Duong A. C., Bach T.-H. L., Tan V. Y., Chatterjee S. S., Cheung G. Y. C., Otto M. (2012) How Staphylococcus aureus biofilms develop their characteristic structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1281–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spaulding A. R., Salgado-Pabón W., Kohler P. L., Horswill A. R., Leung D. Y. M., Schlievert P. M. (2013) Staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigen exotoxins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 26, 422–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddadin R. N. S., Saleh S., Al-Adham I. S. I., Buultjens T. E. J., Collier P. J. (2010) The effect of subminimal inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on virulence factors expressed by Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108, 1281–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung J.-W., Karau M. J., Greenwood-Quaintance K. E., Ballard A. D., Tilahun A., Khaleghi S. R., David C. S., Patel R., Rajagopalan G. (2014) Superantigen profiling of Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 79, 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajagopalan G., Singh M., Sen M. M., Murali N. S., Nath K. A., David C. S. (2005) Endogenous superantigens shape response to exogenous superantigens. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12, 1119–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tilahun A. Y., Karau M. J., Clark C. R., Patel R., Rajagopalan G. (2012) The impact of tacrolimus on the immunopathogenesis of staphylococcal enterotoxin-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome and pneumonia. Microbes Infect. 14, 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopalan G., Smart M. K., Cheng S., Krco C. J., Johnson K. L., David C. S. (2003) Expression and function of HLA-DR3 and DQ8 in transgenic mice lacking functional H2-M. Tissue Antigens 62, 149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng S., Smart M., Hanson J., David C. S. (2003) Characterization of HLA DR2 and DQ8 transgenic mouse with a new engineered mouse class II deletion, which lacks all endogenous class II genes. J. Autoimmun. 21, 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tilahun A. Y., Marietta E. V., Wu T.-T., Patel R., David C. S., Rajagopalan G. (2011) Human leukocyte antigen class II transgenic mouse model unmasks the significant extrahepatic pathology in toxic shock syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 2760–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karau M. J., Tilahun A. Y., Schmidt S. M., Clark C. R., Patel R., Rajagopalan G. (2012) Linezolid is superior to vancomycin in experimental pneumonia caused by superantigen-producing staphylococcus aureus in HLA class II transgenic mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5401–5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vojtov N., Ross H. F., Novick R. P. (2002) Global repression of exotoxin synthesis by staphylococcal superantigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10102–10107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campeau M. E. M., Patel R. (2014) Antibiofilm activity of manuka honey in combination with antibiotics. Int. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tilahun A. Y., Chowdhary V. R., David C. S., Rajagopalan G. (2014) Systemic inflammatory response elicited by superantigen destabilizes T regulatory cells, rendering them ineffective during toxic shock syndrome. J. Immunol. 193, 2919–2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tilahun A. Y., Karau M., Ballard A., Gunaratna M. P., Thapa A., David C. S., Patel R., Rajagopalan G. (2014) The impact of Staphylococcus aureus-associated molecular patterns on staphylococcal superantigen-induced toxic shock syndrome and pneumonia. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 468285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoong P., Torres V. J. (2013) The effects of Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins on the host: cell lysis and beyond. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Römling U., Balsalobre C. (2012) Biofilm infections, their resilience to therapy and innovative treatment strategies. J. Intern. Med. 272, 541–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangalam A. K., Rajagopalan G., Taneja V., David C. S. (2008) HLA class II transgenic mice mimic human inflammatory diseases. Adv. Immunol. 97, 65–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chowdhary V. R., Tilahun A. Y., Clark C. R., Grande J. P., Rajagopalan G. (2012) Chronic exposure to staphylococcal superantigen elicits a systemic inflammatory disease mimicking lupus. J. Immunol. 189, 2054–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seth A. K., Geringer M. R., Hong S. J., Leung K. P., Galiano R. D., Mustoe T. A. (2012) Comparative analysis of single-species and polybacterial wound biofilms using a quantitative, in vivo, rabbit ear model. PLoS ONE 7, e42897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrido V., Collantes M., Barberán M., Peñuelas I., Arbizu J., Amorena B., Grilló M.-J. (2014) In vivo monitoring of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infections and antimicrobial therapy by [18F]fluoro-deoxyglucose-MicroPET in a mouse model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 6660–6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engels B., Chervin A. S., Sant A. J., Kranz D. M., Schreiber H. (2012) Long-term persistence of CD4(+) but rapid disappearance of CD8(+) T cells expressing an MHC class I-restricted TCR of nanomolar affinity. Mol. Ther. 20, 652–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotsougiani D., Pioch M., Prior B., Heppert V., Hänsch G. M., Wagner C. (2010) Activation of T lymphocytes in response to persistent bacterial infection: induction of CD11b and of Toll-like receptors on T cells. Int. J. Inflamm. 2010, 526740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]