Abstract

Background

Nicotine and alcohol are the two most co-abused drugs in the world suggesting a common mechanism of action may underlie their rewarding properties. While nicotine elicits reward by activating ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopaminergic (DAergic) neurons via high affinity neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), the mechanism by which alcohol activates these neurons is unclear.

Methods

Because the majority of high affinity nAChRs expressed in VTA DAergic neurons contain the α4 subunit, we measured ethanol-induced activation of DAergic neurons in midbrain slices from two complementary mouse models, an α4 knock-out (KO) mouse line and a knock-in line (Leu9’Ala) expressing α4 subunit-containing nAChRs hypersensitive to agonist compared to wild-type (WT). Activation of DAergic neurons by ethanol was analyzed using both biophysical and immunohistochemical approaches in midbrain slices. The ability of alcohol to condition a place preference in each mouse model was also measured.

Results

At intoxicating concentrations, ethanol activation of DAergic neurons was significantly reduced in α4 KO mice compared to WT. Conversely, in Leu9’Ala mice, DAergic neurons were activated by low ethanol concentrations that did not increase activity of WT neurons. In addition, alcohol potentiated the response to ACh in DAergic neurons, an effect reduced in α4 KO mice. Paralleling alcohol effects on DAergic neuron activity, rewarding alcohol doses failed to condition a place preference in α4 KO mice, whereas a sub-rewarding alcohol dose was sufficient to condition a place preference in Leu9’Ala mice.

Conclusions

Together, these data indicate that nAChRs containing the α4 subunit modulate alcohol reward.

Keywords: dopamine, alcoholism, reward, acetylcholine, mice, nicotinic receptor

INTRODUCTION

As many as 88-96 % of alcoholics are also smokers and the majority of smokers (~60 %) binge drink or consume significant amounts of alcohol [1, 2]. These statistics suggest that the abusive properties of tobacco and alcohol may, at least partly, share a common mechanism of action. Alternatively, the effects of one drug may modulate the rewarding properties of the other. Indeed, within the mesocorticolimbic reward circuitry of the brain, both drugs stimulate dopaminergic (DAergic) neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), ultimately increasing dopamine (DA) release in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), a phenomenon widely associated with drug reinforcement [3-6]. However, while nicotine initiates activation of DAergic neurons by binding to and activating neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [6, 7], the mechanism by which alcohol activates DAergic neurons is unclear [4, 8, 9].

Neuronal nAChRs are ligand-gated cation channels that, under normal conditions, are activated by the endogenous neurotransmitter, ACh [10, 11]. Twelve vertebrate genes encoding neuronal nAChR subunits have been identified (α2-α10, β2-β4) with five subunits coassembling to form a functional receptor [10, 12]. The majority of nAChRs with high affinity for agonist are heteromeric consisting of two or three α subunits co-assembled with two or three β subunits while a subset of low affinity receptors are homomeric, mostly consisting of α7 subunits [10].

While alcohol is not a direct agonist of nAChRs, it has been hypothesized that ethanol induces an increase in ACh release from lateral dorsal tegmentum (LDTg) cholinergic neuron input into the VTA which could potentially drive activation of DAergic neurons through nAChRs [13]. Ethanol also potentiates the response to ACh for high affinity, but not low affinity nAChRs [14, 15], but whether potentiation occurs in DAergic neurons is unknown. Systemic injection or VTA infusion of the non-selective nAChR antagonist mecamylamine reduces ethanol induced NAcc DA release, alcohol consumption and reinforcement in rodents [16-19]. Furthermore, mecamylamine has been shown to reduce the voluntary subjective euphoric effects of alcohol [20]. More recently, the FDA approved smoking cessation drug, varenicline, can reduce alcohol consumption and seeking in rodents, partly via an α4* nAChR-dependent mechanism (* denotes that other subunits in addition to α4 are components of the functional receptors). Varenicline also reduces consumption in heavy smoking alcoholics [21-25]. While these data implicate a role for nAChRs in alcohol consumption and reinforcement, a direct involvement of nAChR function in alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons has not been demonstrated.

We sought to test the hypothesis that nAChRs contribute to alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons and that alcohol reward could be modulated via α4* nAChR activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, West Grove, PA, USA) were used in all experiments, in addition to α4 knockout (KO) homozygous mice, Leu9’Ala heterozygous and their respective wild-type (WT) littermates as indicated. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals provided by the National Research Council [26], as well as with an approved animal protocol from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Slice preparation

Mice (4-6 weeks old) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg) and then decapitated. Brain slices were cut as previously described [27]. Also see supplemental materials.

Electrophysiological recordings

Individual slices were transferred to a recording chamber continually superfused with oxygenated ACSF (30–32 °C) at a flow rate of ~ 2 ml/min. Cells were visualized using infrared differential interference contrast (IR–DIC) imaging on an Olympus BX-50WI microscope. Electrophysiological recordings were recorded using a Multiclamp 700B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). For a detailed description of recording methodology, see supplemental materials and methods.

Immunohistochemistry

Adult (8-10 weeks) male α4 KO mice and their WT littermates, as well as heterozygous Leu9’Ala mice and their WT littermates were i.p. injected with saline for three days prior to the start of the experiment to habituate them to handling and to reduce c-Fos activation due to stress. Mice were injected with ethanol and their brains were harvested and processed for immunohistochemistry 90 min post injection (see supplemental material and methods for details).

Conditioned Place Preference

The ethanol conditioned place preference (CPP) assay consisted of a three chamber apparatus (Med Associates). The two conditioning chambers were contextually distinct: One had white walls while the other had black walls and one chamber had mesh metal floors while the other had rod metal floors. The conditioning chambers were separated by a neutral grey chamber. Experiments were conducted over 6 consecutive days as in Gibb et al. 2011 [28] (also see supplemental materials).

Ethanol metabolism

Prior to an ethanol injection, blood was obtained from the tail vein (~30 μL each time point) to provide a zero point for each animal. After a 2 g/kg i.p. injection of ethanol, blood samples were taken at intervals of 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. Blood was collected in heparinized capillary tubes, centrifuged at 1500×g for 5 minutes and blood analyzed using an alcohol oxidase-based assay. Blood ethanol concentrations were measured on a GM7 Micro-Stat Analyzer (Analox Instruments Ltd.)

Data analysis

AP spikes were detected using a threshold detection protocol contained within pClampfit (pClamp v10.2, Axon Inst., Molecular Devices). Average fold changes in AP frequency are presented as means ± standard errors of means (SEM). A Paired T-test was used to analyze differences between AP frequency at baseline (1 minute prior to drug application) and after a 5-min application of ethanol. Behavioral and immunohistochemistry data were analyzed using One-way or Two-way ANOVAs with genotype and treatment as variables followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests as indicated. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05. All data are expressed as means ± standard errors of means (SEM).

RESULTS

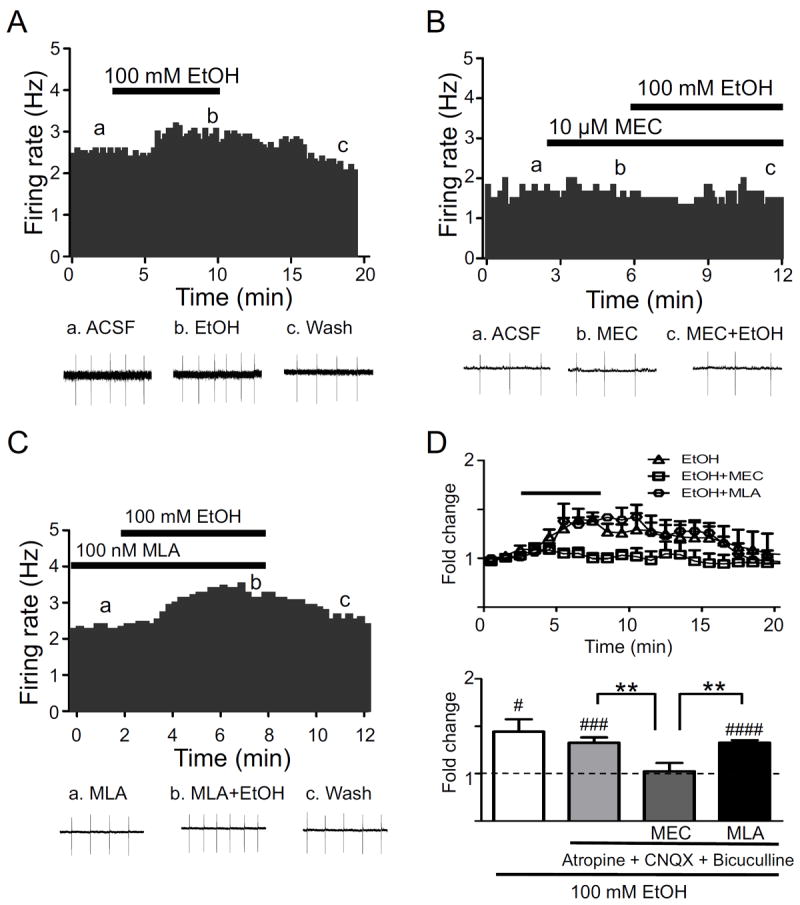

Cell-attached patch clamp recordings were made from VTA DAergic neurons in C57BL/6J mouse slices. Slices were cut in the sagittal plane allowing for preservation of cholinergic input from LDTg into the VTA (see supplemental materials). To test the effects of ethanol on DAergic neuron activity, AP frequency was monitored in cell-attached mode at baseline, during application of an intoxicating concentration of alcohol (100 mM), and after wash-out. Because the focus of our experiments was to uncover the contribution of nAChR activation in response to alcohol, recordings were made in the presence of a cocktail of inhibitors to block muscarinic receptor, AMPA receptor, and GABAA receptor activities (see methods). Five-minute bath application of 100 mM ethanol produced a significant increase in AP frequency (~33 % increase from baseline, Fig 1A, D) that was completely reversed upon wash out. To determine if the inhibitor cocktail affected the firing rates of DAergic neurons in response to alcohol, we measured alcohol responses in the absence of antagonists. Bath application of 100 mM ethanol produced a significant increase in AP frequency that was slightly larger than responses in the presence of the inhibitor cocktail but this increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 1D, bottom panel). Thus, the inhibitor cocktail was included in the remainder of slice physiology experiments. To test the hypothesis that activation of nAChRs is necessary for the observed ethanol-mediated increase in VTA DAergic neuron activity, we bath-applied 10 μM mecamylamine prior to and during application of ethanol. Mecamylamine alone did not affect baseline firing of VTA DAergic neurons (Fig. 1B, D top panel). However, in the presence of mecamylamine, alcohol failed to significantly increase DAergic neuron activity above baseline (Fig. 1B, D) indicating that nAChR activation is necessary for alcohol-induced activation of DAergic neurons. To test the hypothesis that activation of low affinity α7 nAChRs were critical for the observed alcohol-induced increase in DAergic neuron activity, we bath-applied the α7 selective antagonist MLA (10 nM) prior to and during application of ethanol. MLA had little effect on baseline firing of DAergic neurons (Fig. 1C, D top panel). However, in contrast to mecamylamine, ethanol significantly increased DAergic neuron activity compared to baseline (~33 %) in the presence of MLA suggesting that nAChRs containing the α7 subunit do not contribute to ethanol-mediated activation of VTA DAergic neurons (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1.

Ethanol activation of VTA DAergic neurons. A) Representative action potential firing frequency histogram from a VTA DAergic neuron before, during, and after 5-min bath application of 100 mM ethanol (EtOH) alone (n = 10) or in the presence of B) 10 μM mecamylamine (MEC, n = 7) or C) 100 nM MLA (n = 5). Action potentials were recorded in cell-attached mode. Representative action potential traces (top of each panel, a, b, c) are shown from the corresponding times on the histograms. D. Average time course of ethanol responses in each condition is shown (top panel). Each data point represents the average 1-min firing frequency normalized to baseline for each recording. The bar over the averaged frequency plot represents the duration of ethanol application. Recording times between groups were aligned based on time of ethanol application to facilitate comparison. Antagonists were applied at times indicated in the individual histograms as indicated in B and C. (Bottom panel) Fold-change in average firing frequency at baseline (1 min. prior to alcohol application, dotted line) compared to 5 min of ethanol application for each condition. ### p < 0.001, #### p < 0.0001, baseline frequency (1 min prior to drug application) compared to 5 min alcohol exposure, paired t-tests. ** p < 0.01, Students t-test (effect of ethanol or ethanol + MLA on AP frequency compared to ethanol + MEC). n = 6-10 neurons/condition.

Expression of α4* nAChRs modulates alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons

As previous studies indicate that the majority of high affinity nAChRs in VTA DAergic neurons express the α4 subunit and that nAChRs containing the α4 subunit are both necessary and sufficient for nicotine reward [29-31], we sought to investigate the contribution of α4* nAChRs to alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons in two complementary mouse models, the α4 KO mouse which does not express α4* nAChRs [32] and a knock-in mouse line that expresses a single point mutation (Leu9’Ala) in the α4 subunit that renders receptors containing the subunit hypersensitive to agonist [30, 33].

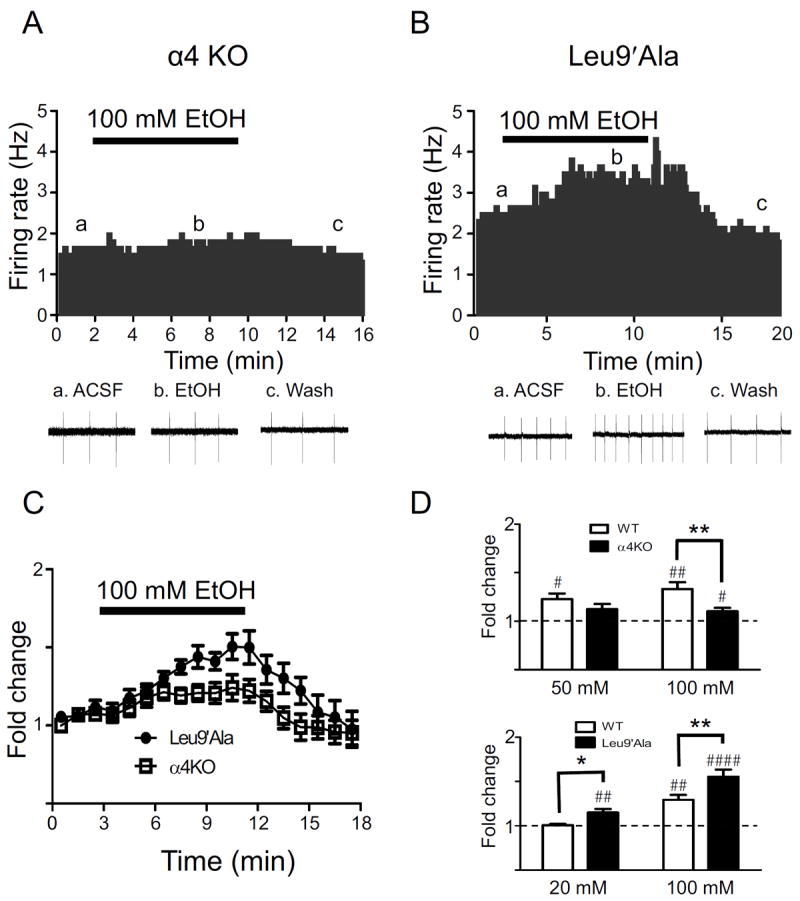

No significant difference in baseline firing frequency of DAergic neurons was observed between WT and α4 KO animals (5.0 ± 1.8 and 4.0 ± 1.0 Hz, respectively) as reported previously [27, 29]. In WT mice, bath application of 50 or 100 mM alcohol significantly increased DAergic neuron activity (~23 % and ~33 % above baseline, Fig. 2D, top panel). In contrast, 50 mM ethanol did not significantly increase VTA DAergic neuron activity of α4 KO mice compared to baseline; whereas 100 mM ethanol elicited a modest increase (~10 % above baseline, Fig. 2A, C, D top panel) compared to baseline. This increase was significantly lower than the effect of 100 mM alcohol on WT DAergic neurons (Fig. 2D top panel).

Figure 2.

Functional α4* nAChR expression modulates DAergic neuron activation by ethanol. Representative action potential firing frequency histogram from a VTA DAergic neuron before, during, and after a 5-min bath application of 100 mM ethanol in sagittal midbrain slices from A) α4 KO and B) Leu9’Ala mice. Representative action potential traces (top of each panel, a, b, c) are shown from the corresponding times on the histograms. C) Time course of the effects of ethanol on average normalized frequency for each genotype are shown (n = 8-10 neurons/genotype). Ethanol (100 mM) was applied at the times indicated by the bar. D. Fold-change in average firing frequency in response to 100 mM ethanol in WT (n = 8) and α4 KO mice (n = 15), 20 mM in WT (n = 5) and Leu9’Ala mice (n = 8), and 100 mM ethanol in WT (n = 10) and Leu9’Ala mice (n = 13). #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001, as in 2D. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 response to alcohol compared between genotypes, One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test.

There was no significant difference in baseline DAergic neuron firing rates between Leu9’Ala mice and their WT littermates. However, in contrast to α4 KO mice, Leu9’Ala DAergic neurons were robustly activated by 100 mM alcohol (Fig. 2B, C, D bottom panel). Whereas WT DAergic neurons responded to 100 mM alcohol by an increased firing rate of ~30 % compared to baseline, Leu9’Ala DAergic neurons increased ~60 %, and was significantly different from WT (Fig. 2B, D bottom panel). To test the hypothesis that low sub-activating alcohol concentrations are sufficient to increase VTA DAergic neuron firing rates in Leu9’Ala mice, DAergic activity was also recorded in response to 20 mM alcohol. At this concentration, alcohol did not significantly increase VTA DAergic neurons firing rates compared to baseline in WT slices (Fig. 2D bottom panel). By contrast, 20 mM alcohol elicited a modest (~15 %), but significant increase in DAergic neuron activity in Leu9’Ala slices. Together, these data indicate that activation of α4* nAChRs can contribute to alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons.

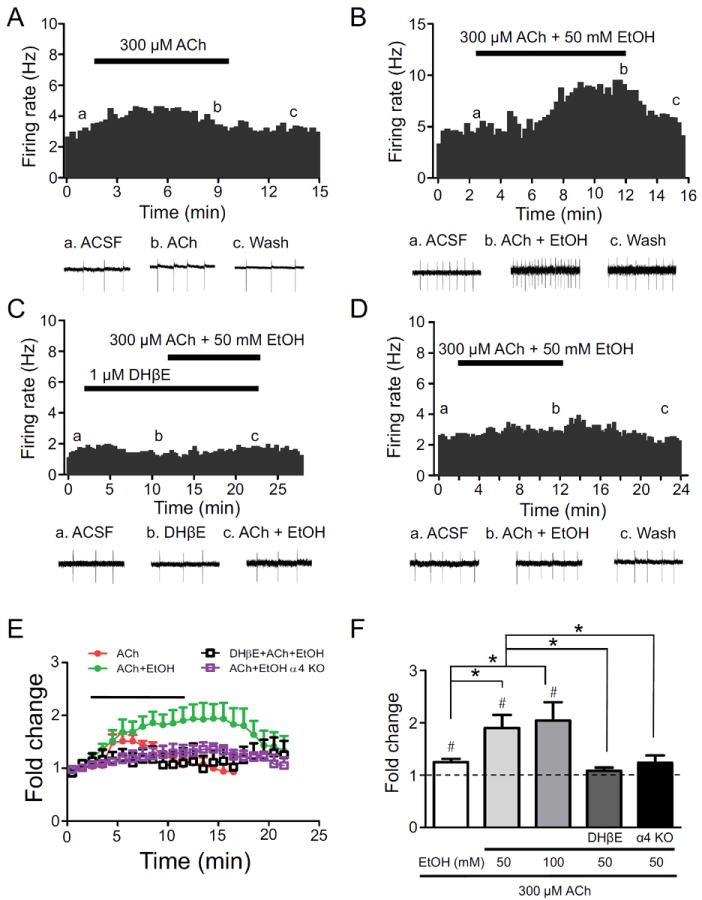

Alcohol potentiates the response to ACh in DAergic neurons by an α4* nAChR-dependent mechanism

To test the hypothesis that ethanol may potentiate the response to ACh in VTA DAergic neurons, we bath-applied ACh (300 μM) in the absence and presence of alcohol and measured effects on firing frequency. In WT mice, ACh alone elicited an increase in VTA DAergic neuron firing frequency that was significantly greater than baseline (~25 %, Fig 3A, E, F)). Co-application of either 50 or 100 mM ethanol with ACh elicited a robust increase in firing frequency (~2 fold) which was significantly greater than the response of ACh alone and persisted for several minutes after application before returning to baseline (Fig. 3B, E, F). Pre-incubation of the slice with DHβE significantly reduced the response to ACh plus 50 mM ethanol (Fig. 3C, E, F). Finally, the effect of ACh plus 50 mM ethanol on DAergic neuron firing frequency was significantly reduced in slices from α4 KO mice compared to WT slices (Fig. 3D, E, F). Together, these data indicate that alcohol potentiates the response to ACh at α4* nAChRs.

Figure 3.

Alcohol potentiates the response of DAergic neurons to ACh. A) Representative action potential firing frequency histogram from a VTA DAergic neuron before, during, and after 10-min bath application of 300 μM ACh. Representative action potential traces (top of each panel, a, b, c) are shown from the corresponding times on the histograms. Representative action potential firing frequency histogram from a VTA DAergic neuron before, during, and after 10-min bath co-application of 300 μM ACh and 50 mM ethanol in the absence (B), or presence (C) of 1 μM DHβE. D) Representative action potential firing frequency histogram from an α4 KO VTA DAergic neuron before, during, and after 10 min bath co-application of 300 μM ACh and 50 mM ethanol. E) Time course of the effects of ethanol on average normalized frequency under each condition are shown (n = 6-12 neurons/genotype). ACh ± ethanol was applied at the times indicated by the bar. Recording times between groups were aligned based on time of ethanol application to facilitate comparison. F) Fold-change in average DAergic neuron firing frequency in response to 300 μM ACh alone (n = 6), in the presence of 50 (n = 12) or 100 mM (n = 5) ethanol, in the presence of 50 mM ethanol and DHβE (n = 6), or in the presence of 50 mM ethanol in α4 KO slices (n = 10). #p < 0.05 as in 1D. * p < 0.05 response to alcohol compared between treatments/genotypes.

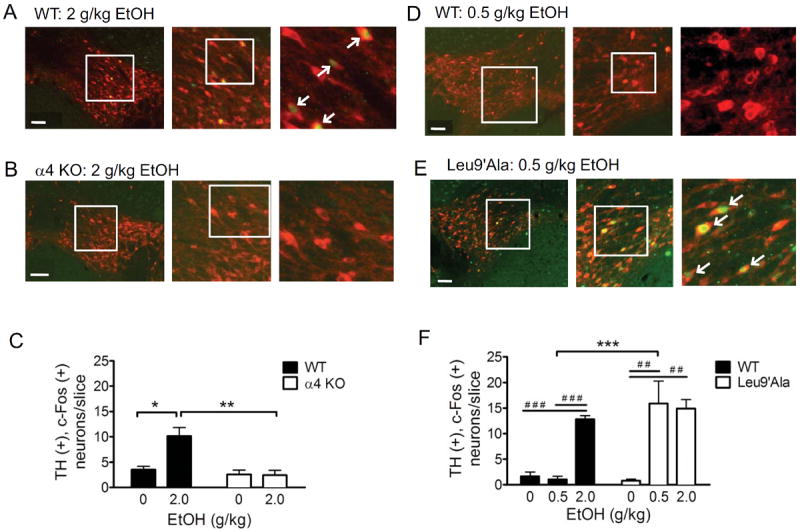

Alcohol induction of c-Fos expression in VTA DAergic neurons requires functional expression of α4* nAChRs

Previously, using c-Fos as a marker for neuronal activation and TH as a marker for DAergic neurons, we demonstrated that ethanol activates DAergic neurons of the VTA and that this activation can be blocked by a pre-injection of the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine [19]. To determine if α4* nAChRs are necessary for this activation, we challenged WT and α4 KO mice with saline or 2.0 g/kg ethanol and examined their brains for c-Fos expression within TH(+) neurons 90 min. post-injection (Fig. 4). Because previous studies indicate alcohol induces c-Fos in DAergic neurons preferentially in the posterior VTA [24, 34], we focused on this region for analysis. Overall there was a significant main effect of genotype (F(1,8) = 8.15, p<0.05), treatment (F(1,8) = 12.28, p<0.01) and a significant genotype × treatment interaction (F(1,8) = 13.25, p<0.01). Bonferroni post-test indicated a significant difference between number of TH(+), c-Fos(+) neurons in WT and α4 KO mice after 2.0 g/kg ethanol, but not saline (Fig. 4A, B, C). In addition, the % of TH(+) neurons that were also c-Fos(+) significantly differed between WT and α4 KO mice after 2.0 g/kg ethanol, but not saline (Table S1). WT mice injected with 2.0 g/kg ethanol had significantly higher expression of c-Fos compared to α4 KO mice injected with 2.0 g/kg ethanol (Fig 4C,). One-way ANOVA also indicated that WT mice treated with 2.0 g/kg ethanol had significantly increased c-Fos expression compared to a saline injection (Fig 4C), whereas the same dose of ethanol had no effect in α4 KO mice compared to a saline injection.

Figure 4.

Ethanol-induced c-Fos expression in VTA TH(+) neurons is dependent on expression and activation of α4* nAChRs. Representative photomicrographs illustrating midbrain sections of the posterior VTA from A) WT mice and B) α4 KO mice injected with 2 g/kg ethanol. Sections were immunolabeled for TH (red) and c-Fos (green). White boxes delineate slice regions that are magnified in the adjacent photomicrographs. White arrowheads point to neurons that are TH (+), c-Fos (+). Scale bar = 100 μm. Merged images are shown. C) Number of TH (+) c-Fos (+) neurons per slice taken from mice given an i.p. injection of 2 g/kg ethanol. Forty-eight slices/treatment/mouse were analyzed, n = 3 mice/treatment. D. Representative photomicrographs illustrating midbrain sections of the posterior VTA from WT mice and E) Leu9’Ala mice injected with 0.5 g/kg ethanol. Sections were immunolabeled for TH and c-Fos as in panels A and B. F) Average number of TH (+), c-Fos (+) neurons/slice calculated from mice given an i.p. injection of 0.5 g/kg or 2 g/kg ethanol. Forty-eight slices/treatment/mouse were analyzed, n = 3 mice/treatment. One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test comparing saline to ethanol treatments in WT, α4 KO, or Leu9’Ala mice was used, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test comparing treatments in WT and α4 KO mice was also used, ** p < 0.01, ***p<0.001.

To determine if increasing α4* nAChR agonist sensitivity resulted in activation of VTA DAergic neurons with lower doses of alcohol, we challenged WT and Leu9’Ala mice with two concentrations of ethanol, 2.0 g/kg and a low dose of 0.5 g/kg, and analyzed their brains for c-Fos expression in TH(+) neurons as above. Two-Way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of treatment (F(2,14) = 22.01, p < 0.001), genotype (F(1,14) = 11.65, p < 0.01) and a significant treatment × genotype interaction (F(2,14) = 8.97, p < 0.01). A Bonferroni post-test indicated that Leu9’Ala mice treated with 0.5 g/kg had significantly increased number of TH(+), c-Fos(+) neurons compared to WT mice (Fig 4D, E, F). The % of total TH(+) neurons that were also c-Fos(+) was increased in Leu9’Ala mice compared to WT after a 0.5 g/kg ethanol challenge (Table S1). Additionally, one-way ANOVAs revealed that Leu9’Ala mice treated with 0.5 g/kg and 2.0 g/kg ethanol had significantly increased numbers of TH(+), c-Fos(+) neurons compared to a saline challenge while WT mice treated with 2.0 g/kg had significantly increased numbers of TH(+), c-Fos(+) neurons compared to both saline and 0.5 g/kg alcohol. Together, these data indicate that expression of α4* nAChRs are necessary for alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons and that α4* nAChR activation controls DAergic neuron response to alcohol.

Functional expression of α4* nAChRs modulates alcohol reward

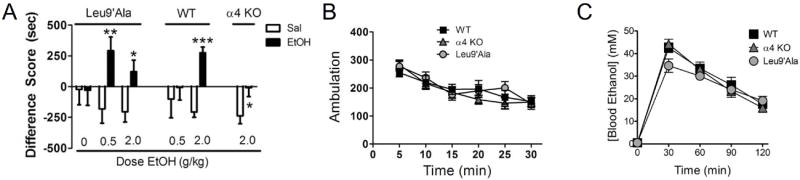

As activation of VTA DAergic neurons is sufficient for reward [5], and both our physiology and immunohistochemical data indicate a role for α4* nAChRs in alcohol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons, we evaluated alcohol rewarding properties in α4 KO and Leu9’Ala mouse lines using the CPP assay, a robust behavioral assay of rewarding stimuli [35]. In C57BL/6J mice, the background strain for both α4 mouse models, 2.0 g/kg has been established as a rewarding dose of alcohol [36]. Consistent with this observation, WT mice that received i.p. injections of 2.0 g/kg ethanol in the drug-paired chamber significantly preferred the alcohol-paired chamber over the saline-paired chamber after training compared to baseline (expressed as the difference score, post-training minus pre-training for each chamber, F(1, 48) = 58.2, p < 0.001, Fig. 5A). In addition, the total time spent in the alcohol-paired chamber after training was greater that the time spent in the same chamber before training (Table S2, F(1, 48) = 22.0, p < 0.001). In α4 KO mice, there was a modest but statistically significant difference in the difference score between ethanol-paired and saline-paired chambers (p < 0.05, F(1, 20) = 5.6, Fig. 5A). However, the ethanol difference score in α4 KO mice was significantly lower than the equivalent ethanol difference score in WT mice (F(1, 34) = 9.49, p < 0.01). In addition, α4 KO mice did not spend significantly greater time in the alcohol-paired chamber during the test day compared to the pre-training, habituation day (Table S2, NS) indicating that this alcohol dose was weakly rewarding in these animals. To test the hypothesis that Leu9’Ala mice are more sensitive to alcohol reward, we tested a sub-rewarding dose of alcohol, 0.5 g/kg, in these animals. In WT mice, 0.5 g/kg ethanol failed to condition a place preference (Fig. 5A, NS). However, Leu9’Ala mice significantly preferred the alcohol-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber (Fig. 5A, F(1,22) = 8.57, p < 0.01). Leu9’Ala mice also spent significantly more total time in the alcohol-paired chamber during the post-training test day compared to the pre-training habituation day, indicating a low dose of alcohol was rewarding in these animals (Table S2, F(1,22) = 8.33, p < 0.01). In response to 2.0 g/kg alcohol, Leu9’Ala mice displayed a more modest preference for the ethanol-paired compared to the saline-paired chamber (F(1, 22), p < 0.05). However, total time spent in the ethanol paired chamber after training did not reach significance compared to time spent in the alcohol-paired chamber during habituation. Thus, alcohol displayed an inverted “U” shaped dose response relationship in Leu9’Ala mice. As a negative control in Leu9’Ala mice we also measured time spent in the drug paired chamber in response to saline injections in both chambers during training. There was no significant preference for either chamber after training with saline injections nor was there a difference in time spent during the saline-paired chamber during the test day compared to the habituation day, indicating a specific effect of the low alcohol dose in these animals (Fig. 5A, Table S2). Because genotype differences in locomotor activity could influence CPP results, we measured baseline locomotion in WT, α4 KO, and Leu9’Ala mice. No significant differences in activity were detected over the course of 30 min (Fig. 5B). Finally, differences in rewarding properties of alcohol between WT, α4 KO and Leu9’Ala mice could be a consequence of altered pharmacokinetics of ethanol between genotypes. To address this possibility, we measured blood ethanol concentrations (BEC) in WT, α4 KO, and Leu9’Ala mice every 30 min after an acute i.p. injection of 2.0 g/kg to monitor alcohol clearance (Fig. 5C). Two-Way ANOVA revealed an overall significant effect of time (F(4,44) = 139.0, p < 0.0001) but not genotype on BEC. In addition, there was no significant time × genotype interaction. Together, these data indicate that activation of α4* nAChRs modulates alcohol reward.

Figure 5.

α4* nAChR expression modulates alcohol reward. A. Average difference score (test – baseline) in ethanol-paired (black bars) and saline-paired (white bars) chambers in Leu9’Ala, WT, and α4 KO mice in response to the alcohol doses indicated. Because each line has been back-crossed at least ten generations to the C57Bl/6J strain and no differences in alcohol responses between α4 KO and Leu9’Ala WT littermates were detected, WT mice were combined. n = 9 – 22 mice/dose. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to saline. B. Locomotor activity (ambulation) in WT, Leu9’Ala, and α4 KO mice. Each data point represents the average total locomotor activity over 5-min (n=5-10 mice/genotype). C. Blood ethanol concentration at 30-min intervals after an acute, 2.0 g/kg i.p. injection of alcohol in WT, α4 KO, and Leu9’ala mice (n = 3-4 mice/genotype).

DISCUSSION

Alcohol and nicotine are often co-abused suggesting that they may share a common mechanism of action in the CNS. Here we show that, in VTA midbrain slices, alcohol significantly increased DAergic neuron activity, an effect that was blocked by mecamylamine indicating a critical role for nAChRs in alcohol-induced activation of these neurons. This observation is also in agreement with our previous data illustrating that mecamylamine prevents alcohol-induced c-Fos expression in VTA DAergic neurons after an alcohol challenge [19].

Previously, we demonstrated that VTA DAergic neurons that are activated by alcohol, robustly express α4, α6, and β3 nAChR subunits [24]. In addition, the smoking cessation aid, varenicline, targets VTA α4β2* nAChRs to reduce alcohol consumption [24, 25] although other nAChR subtypes in additional brain regions may also contribute [23, 37]. Using two complementary genetic mouse models, our data indicate that α4* nAChRs are important for ethanol-induced activation of VTA DAergic neurons. A leftward shift of the agonist sensitivity of these receptors [38] lowered the concentration of alcohol required to activate these neurons, indicating that α4* nAChR agonist sensitivity can directly modulate VTA DAergic neuron activation by alcohol. Finally, ethanol potentiated DAergic neuron activation by ACh, a phenomenon that was blocked by DHβE and reduced in α4 KO slices. It is important to note that alcohol responses in α4 KO DAergic neurons were not completely abolished indicating other nAChR subtypes or non-nAChR mechanisms may be involved. However, these data indicate that if alcohol increases ACh concentration in the VTA, then not only will elevated ACh concentrations activate DAergic neuron nAChRs, but alcohol will potentiate this response. One limitation of our physiology data stems from the fact that mesocortical slices may not include critical circuitry influencing VTA activity. In addition, we did not differentiate sub-populations of DAergic neurons that may exist and express distinct nAChR subtypes within the VTA (although the vast majority express α4* nACRs)[29, 39]. Interestingly, expression and function of α4* nAChRs not only contributed to activation of DAergic neurons in slices, but also modulated ethanol induction of c-Fos expression in VTA DAergic neurons. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that expression of functional α4* nAChRs can modulate activation of the mesolimbic reward pathway by alcohol.

Previous studies indicate that the rewarding properties of ethanol, as measured by CPP, is expressed through a VTA-dependent mechanism [40]. Thus, because alcohol activation of DAergic neurons is reduced in α4 KO mice, alcohol CPP is weak in these animals, although it is possible that alcohol may condition a place preference in response to higher doses of alcohol. Conversely, a sub-rewarding dose of alcohol is sufficient to condition a place preference in Leu9’Ala mice, presumably because VTA DAergic neurons in these animals are more robustly activated by such low doses of alcohol. Previous data indicate that α4 KO mice acutely consume less alcohol than WT mice in the drinking-in-the-dark paradigm consistent with a role for α4* nAChRs in reward [24, 25]. However, when given a 2 % or 20 % alcohol bottle in the DID assay, Leu9’Ala mice alcohol consumption did not significantly differ compared to WT mice. This may be due to the fact that consumption was analyzed immediately after saline or drug injections which could influence consumption behavior. Thus, baseline consumption behavior should be measured in Leu9’Ala mice using a variety of alcohol concentrations in the absence of injections. Because blocking alcohol reward might reduce alcohol consumption, our data raise the possibility that α4* nAChRs in the VTA may be useful molecular targets for alcohol cessation therapies. Indeed, in addition to varenicline, recently sazetidine-A, an α4β2-selective nAChR desensitizing agent, has been shown to reduce alcohol consumption in rodents [41].

Prior studies using nAChR subtype-selective antagonists have attempted to identify the subunit composition of nAChRs that may influence alcohol-induced DA release in NAcc and alcohol self-administration in rodents. Our lab and others have found that systemic injection of MLA does not reduce alcohol consumption in rodents [19, 42, 43] indicating that low affinity α7 nAChRs do not play a significant role in alcohol reward. This is also in agreement with our physiology data indicating a lack of effect of MLA on ethanol-induced activation of DAergic neurons. In addition, systemic injection of the α4β2* nAChR competitive antagonist DHβE also fails to reduce ethanol intake in both rats and mice [43, 44] at lower doses but has been shown to reduce self-administration in rats at higher doses [45]. Thus, it is likely that the ability of DHβE to block α4β2* nAChRs depends on the stoichiometry of the target receptor population [46] and subunit composition. For example, we recently identified functional nAChRs in VTA DAergic neurons that are of the α4α6(β2)(β3) subtype [27] which we would expect to be more resistant to blockade by DHβE compared to nAChRs consisting of purely α4 and β2 subunits [47]. Although a recent study found that α6 and β3 KO mice did not consume or prefer alcohol differently than WT mice, caution in interpretation is warranted as these KO animals may exhibit compensatory changes in nAChR expression during development that may influence alcohol reinforcement [48]. Thus, further experiments will need to be done to identify additional nAChR subunits involved in alcohol-mediated activation of VTA DAergic neurons and alcohol reward.

To our knowledge, this is the first study directly implicating α4* nAChRs -molecules that are known to play a primary role in nicotine reward- in the rewarding properties of alcohol. Our data indicate that activation of α4* nAChRs in the VTA modulates alcohol reward, suggesting their potential usefulness as therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism award number R01AA017656 (ART) and F31AA018915 (L.M.H.) and the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke award number R01NS030243 (PDG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures. The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Batel P, Pessione F, Maitre C, Rueff B. Relationship between alcohol and tobacco dependencies among alcoholics who smoke. Addiction. 1995;90:977–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90797711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, Melton LJ., 3rd Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. Role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA. 1996;275:1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodd ZA, Melendez RI, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Zhang Y, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of male Wistar rats: evidence for involvement of dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1050–1057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1319-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto T, Harnett MT, Morikawa H. Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) is an ethanol target in midbrain dopamine neurons of mice. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:619–626. doi: 10.1152/jn.00682.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai HC, Zhang F, Adamantidis A, Stuber GD, Bonci A, de Lecea L, Deisseroth K. Phasic firing in dopaminergic neurons is sufficient for behavioral conditioning. Science. 2009;324:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1168878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pidoplichko VI, DeBiasi M, Williams JT, Dani JA. Nicotine activates and desensitizes midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 1997;390:401–404. doi: 10.1038/37120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maskos U, Molles BE, Pons S, Besson M, Guiard BP, Guilloux JP, Evrard A, Cazala P, Cormier A, Mameli-Engvall M, et al. Nicotine reinforcement and cognition restored by targeted expression of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2005;436:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature03694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride WJ, Lovinger DM, Machu T, Thielen RJ, Rodd ZA, Murphy JM, Roache JD, Johnson BA. Serotonin-3 receptors in the actions of alcohol, alcohol reinforcement, and alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:257–267. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113419.99915.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dopico AM, Lovinger DM. Acute alcohol action and desensitization of ligand gated ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:98–114. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapper AR, Nashmi R, Lester HA. Cell Biology of Addiction. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2006. Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors and Nicotine Dependence; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D. The neurobiology of nicotine addiction: bridging the gap from molecules to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsson A, Edstrom L, Svensson L, Soderpalm B, Engel JA. Voluntary ethanol intake increases extracellular acetylcholine levels in the ventral tegmental area in the rat. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:349–358. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardoso RA, Brozowski SJ, Chavez-Noriega LE, Harpold M, Valenzuela CF, Harris RA. Effects of ethanol on recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:774–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuo Y, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom JM, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Alcohol modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is alpha subunit dependent. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blomqvist O, Engel JA, Nissbrandt H, Soderpalm B. The mesolimbic dopamine-activating properties of ethanol are antagonized by mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;249:207–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90434-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Accumbal dopamine overflow after ethanol: localization of the antagonizing effect of mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;334:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ericson M, Blomqvist O, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Voluntary ethanol intake in the rat and the associated accumbal dopamine overflow are blocked by ventral tegmental mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;358:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Tapper AR. Modulation of ethanol drinking-in-the-dark by mecamylamine and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1488-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi H, de Wit H. Mecamylamine attenuates the subjective stimulant-like effects of alcohol in social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:780–786. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065435.12068.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12518–12523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705368104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee SA, Harrison EL, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM, Picciotto MR, Petrakis IL, Estevez N, Balchunas E. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Pang X, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Activation of alpha4* nAChRs is necessary and sufficient for varenicline-induced reduction of alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10169–10176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendrickson LM, Gardner P, Tapper AR. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing the alpha4 subunit are critical for the nicotine-induced reduction of acute voluntary ethanol consumption. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:124–127. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.2.14409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L, Zhao-Shea R, McIntosh JM, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Nicotine Persistently Activates Ventral Tegmental Area Dopaminergic Neurons via Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Containing alpha4 and alpha6 Subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:541–548. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.076661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibb SL, Jeanblanc J, Barak S, Yowell QV, Yaka R, Ron D. Lyn kinase regulates mesolimbic dopamine release: implication for alcohol reward. J Neurosci. 31:2180–2187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5540-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao-Shea R, Liu L, Soll LG, Improgo MR, Meyers EE, McIntosh JM, Grady SR, Marks MJ, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Nicotine-mediated activation of dopaminergic neurons in distinct regions of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1021–1032. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Lester HA. Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306:1029–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, Tolu S, Porcu E, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP, Maskos U, Fratta W. Crucial role of alpha4 and alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12318–12327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3918-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross SA, Wong JY, Clifford JJ, Kinsella A, Massalas JS, Horne MK, Scheffer IE, Kola I, Waddington JL, Berkovic SF, et al. Phenotypic characterization of an alpha 4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knock out mouse. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6431–6441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06431.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fonck C, Cohen BN, Nashmi R, Whiteaker P, Wagenaar DA, Rodrigues Pinguet N, Deshpande P, McKinney S, Kwoh S, Munoz J, et al. Novel seizure phenotype and sleep disruptions in knock in mice with hypersensitive alpha 4* nicotinic receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11396–11411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3597-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Melendez RI, Kuc KA, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Comparison of intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the posterior ventral tegmental area between alcohol-preferring and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1212–1219. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134401.30394.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatterjee S, Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Coe JW, Hurst RS, Shaffer CL, Lowe J, Rollema H, Bartlett SE. Partial agonists of the alpha3beta4* neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor reduce ethanol consumption and seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 36:603–615. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lester HA, Fonck C, Tapper AR, McKinney S, Damaj MI, Balogh S, Owens J, Wehner JM, Collins AC, Labarca C. Hypersensitive knockin mouse strains identify receptors and pathways for nicotine action. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6:633–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang K, Hu J, Lucero L, Liu Q, Zheng C, Zhen X, Jin G, Lukas RJ, Wu J. Distinctive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor functional phenotypes of rat ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons. J Physiol. 2009;587:345–361. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bechtholt AJ, Cunningham CL. Ethanol-induced conditioned place preference is expressed through a ventral tegmental area dependent mechanism. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:213–223. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rezvani AH, Slade S, Wells C, Petro A, Lumeng L, Li TK, Xiao Y, Brown ML, Paige MA, McDowell BE, et al. Effects of sazetidine-A, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor desensitizing agent on alcohol and nicotine self administration in selectively bred alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;211:161–174. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1878-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larsson A, Jerlhag E, Svensson L, Soderpalm B, Engel JA. Is an alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive mechanism involved in the neurochemical, stimulatory, and rewarding effects of ethanol? Alcohol. 2004;34:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsson A, Svensson L, Soderpalm B, Engel JA. Role of different nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mediating behavioral and neurochemical effects of ethanol in mice. Alcohol. 2002;28:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ericson M, Molander A, Lof E, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Ethanol elevates accumbal dopamine levels via indirect activation of ventral tegmental nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;467:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuzmin A, Jerlhag E, Liljequist S, Engel J. Effects of subunit selective nACh receptors on operant ethanol self-administration and relapse-like ethanol-drinking behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moroni M, Zwart R, Sher E, Cassels BK, Bermudez I. alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors with high and low acetylcholine sensitivity: pharmacology, stoichiometry, and sensitivity to long-term exposure to nicotine. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:755–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grady SR, Salminen O, Laverty DC, Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ. The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamens HM, Hoft NR, Cox RJ, Miyamoto JH, Ehringer MA. The alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit influences ethanol-induced sedation. Alcohol. 2012;46:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.