Abstract

While recent evidence has indicated that experienced racial discrimination is associated with increased depressive symptoms for African American adolescents, most studies rely on cross-sectional and short-term longitudinal research designs. As a result, the direction and persistence of this association across time remains unclear. This article examines longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among a community sample of African American adolescents (N = 504) from Grade 7 to Grade 10, while controlling for multiple alternative causal pathways. Sex was tested as a moderator of the link between experienced racial discrimination and later depressive symptoms. Structural equation modeling revealed that experienced racial discrimination was positively associated with depressive symptoms 1 year later across all waves of measurement. The link between experienced racial discrimination at Grade 7 and depressive symptoms at Grade 8 was stronger for females than males. Findings highlight the role of experienced racial discrimination in the etiology of depressive symptoms for African Americans across early adolescence.

Keywords: racial discrimination, African American, adolescents, sex differences

Racial discrimination is a profound and deleterious stressor in the lives of African American adolescents (García Coll et al., 1996; Williams & Mohammed, 2009), as evidenced by positive links between experienced racial discrimination and a myriad of negative mental health outcomes, including low psychological well-being (Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006), conduct problems (e.g., Brody et al., 2006), depression (e.g., Wong, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2003), anxiety (e.g., Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009), violent behavior (e.g., Simons et al., 2006), low self-esteem (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006), high hopelessness (e.g., Nyborg & Curry, 2003), negative academic outcomes (e.g., Chavous, Rivas-Drake, Smalls, Griffin, & Cogburn, 2008), and substance use (e.g., Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004). However, little research has focused on the effects of racial discrimination longitudinally, throughout adolescence. Fewer still have considered whether male and female adolescents are differentially susceptible to the negative effects of racial discrimination. To address these gaps in the literature, the present study investigated prospective associations between racial discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms among a sample of urban African American youth.

Models of Racial Discrimination Effects

Several models have posited racial discrimination as a significant contextual stressor for African American adolescents. As a part of their biopsychosocial model of the experience of racism, Clark, Anderson, Clark, and Williams (1999) hypothesized constitutional, sociodemographic, psychological, and behavioral factors as moderators of the experience of racism stress. Following the experience of racism, the model stipulates that coping responses directly affect an individual’s psychological and physiological stress response and the consequent health outcomes. García Coll and colleagues (1996) theorized that racism and discrimination lead to promoting (e.g., adaptive culture) or inhibiting (e.g., segregation) environments. These factors, in turn, influence child characteristics and the familial environment, thereby affecting cognitive, social, and emotional developmental outcomes. Similarly, Harrell (2000) theorized that race-related stress, including racism-related life events and daily racism microstressors, begins a stress process that leads to physical, psychological, and social difficulties. Grounded in this theoretical foundation positing racial discrimination as stressful and developmentally significant for African American youth, this study investigates racial discrimination as a predictor of depressive symptoms in African American adolescents.

Perceived Racial Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms During Adolescence

A substantial body of research has suggested that rates of depression spike during early adolescence (e.g., Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003), and considerable evidence has indicated that depressive symptoms during adolescence predict psychological dysfunction in adulthood (e.g., Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2009). In parallel with the increase in rates of depression, adolescence is a time in which the effects of racial discrimination are particularly serious for African Americans (Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000), likely due to the acquisition of cognitive capacities and sociocultural awareness that are essential for the perception of social discrimination (Brown & Bigler, 2005). In fact, perceptions of racial discrimination are more common among African American adolescents than African American youth in late childhood (Pachter, Szalacha, Bernstein, & García Coll, 2010). Thus, African American adolescents’ experiences with racial discrimination appear to increase in salience during early adolescence alongside a rise in depression rates.

There is mounting evidence that the parallel onset of depressive symptoms and increased susceptibility to racial stressors for African American adolescents may be linked. Cross-sectional research has documented associations between perceived racial discrimination and depressive symptoms for African American adolescents (e.g., Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009; Sellers et al., 2006), but the lack of temporal precedence between experienced discrimination and depressive symptoms in these studies has forced researchers to rely on theory to suggest the directionality of the racial discrimination–depressive symptoms link. The few available longitudinal studies increase our confidence that depressive symptoms are a consequence of racial discrimination for African American adolescents. For instance, Wong and colleagues (2003) found that racism committed by peers and teachers accounted for increases in African American middle school students’ depressive symptoms between Grades 7 and 8. Brody and colleagues (2006) found that increases in perceived racial discrimination from late childhood to early adolescence predicted depressive symptoms 1 year later. Greene et al. (2006) found that, over a 5-year period, increases in perceived racial discrimination predicted increases in depressive symptoms and decreases in self-esteem in their diverse sample of adolescents. However, these longitudinal studies are qualified by methodological limitations common in longitudinal racial discrimination research. Specifically, much of this research does not control for potential alternative causal pathways such as the influence of past levels of experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms, concurrent associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms, or reciprocal longitudinal associations (e.g., Greene et al., 2006). Such omissions fuel controversy regarding whether negative mood, including depressive symptoms, may lead to increased perceptions of racial discrimination, rather than the reverse (Sechrist, Swim, & Mark, 2003). Furthermore, longitudinal investigations of experienced racial discrimination often use short-term longitudinal designs, with data collected at only two time points (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2004). Thus, two longitudinal patterns remain unclear: the direction of the association between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms and the persistence of this association throughout early adolescence.

Sex as a Moderator of the Association Between Experienced Racial Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms

Prior research has established that sex differences in depression emerge during adolescence, with females two times more likely than males to develop depression by age 15 (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001). The limited research with African American adolescents has suggested a similar pattern (e.g., Dunn & Goodyer, 2006). However, sex differences in depressive symptoms as a result of experienced racial discrimination have been investigated on only a few occasions. Some, albeit limited, quantitative evidence has suggested that females may be more likely than males to internalize racial discrimination stress and, in turn, experience depressive symptoms (e.g., Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2010). Thus, it appears that sex may affect the link between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. Based on previous evidence regarding sex differences in experiences of racial discrimination and coping with depressive symptoms, we expected that females would exhibit an increased susceptibility to depressive symptoms following experiences of racial discrimination.

The Present Study

While prior research has amassed evidence for a contemporaneous association between experiences of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents, longitudinal research is comparatively sparse and methodologically limited. The present study examined longitudinal associations between racial discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms between Grades 7 and 10 among a community sample of urban African American adolescents. The following hypotheses were tested:

Hypothesis 1: Experienced racial discrimination will be associated with subsequent depressive symptoms after controlling for depressive symptoms 1 year earlier, experienced racial discrimination 1 year earlier, contemporaneous links between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms, and the associations between depressive symptoms and subsequent experienced racial discrimination.

Hypothesis 2: The associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms 1 year later will be greater than the associations between depressive symptoms and subsequent experienced racial discrimination.

Hypothesis 3: The association between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms 1 year later will be stronger for females than males.

Method

The original sample consisted of 678 children initially interviewed in the fall of their first grade as a part of a randomized trial of two 1-year universal preventive interventions focusing on learning and aggressive behavior (Ialongo, Werthamer, et al., 1999). Three first-grade classrooms in each of nine public elementary schools in Baltimore City were assigned to one of two intervention conditions (n = 459) or a control condition (n = 219). Five hundred eighty-five of the students who participated in the first-grade assessment were African American. Of these students, 86.2% (n = 504) had parental consent, provided assent, and completed measures of depressive symptoms and racial discrimination between Grade 7 and Grade 10. These 504 participants comprised the sample of interest. Approximately half of the sample was male (n = 269; 53%). At the seventh-grade assessment, youth ranged in age from 11 to 14 (M = 12.8, SD = 0.35). The 504 African American adolescents participating in this study did not differ significantly from the 174 students excluded from the sample with regard to sex (t = 0.41, ns), percentage receiving free or reduced lunch (t = 1.16, ns), age at entry into the study (t = 0.96, ns), or first-grade self-reports of depressive symptoms (t = 0.33, ns). Intervention status was not associated with any study variables.

Procedure

Each year in Grades 7 through 10, adolescents reported their experiences with racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. Informed parental consent and written assent from students were obtained prior to data collection. Data were collected from the majority of the participants (90%) at school during the spring semester or in community locations for youth who had dropped out of school or failed to attend. Face-to-face interviews were used to collect study data; interviewers were predominantly African American.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information including participant age, sex, and receipt of free or reduced lunch was collected. Whether the participant was included in an intervention or control condition also was recorded.

Experienced racial discrimination

Experienced racial discrimination was assessed using seven items drawn from the Racism and Life Experiences Scales (RaLES; Harrell, 1997). Respondents indicated how often they had experienced racial discrimination within the past year (e.g., “How often have others reacted to you as if they were afraid or scared because of your race?” and “How often have you been excluded (left out) from a group activity (game, party, or social event) because of your race?”) using a 6-point frequency scale (1 = never, 2 = less than once a year, 3 = a few times a year, 4 = about once a month, 5 = a few times a month, 6 = once a week or more). One item was excluded from the analysis because it did not load onto the same factor as the other six items. This scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .78 to .85 in Grades 7–10.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 21-item Depression subscale of the Baltimore How I Feel–Adolescent Version, Youth Report (Ialongo, Kellam, & Poduska, 1999).The items comprising this subscale were created using depression criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev.; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) and items from other child self-report measures, such as the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1983) and the Depression Self-Rating Scale (Asarnow & Carlson, 1985). Participants reported the frequency with which they had experienced depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (most times). Cronbach’s alphas for the Depression subscale ranged from .83 to .88 in Grades 7–10.

Data Analytic Strategy

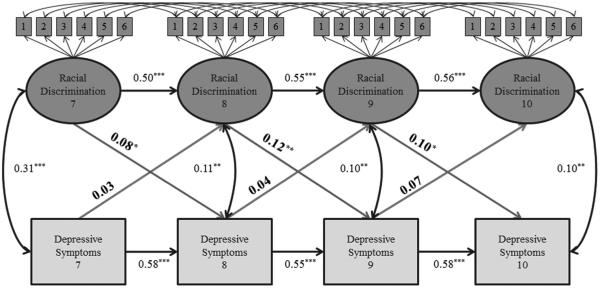

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms 1 year later across a 4-year span while controlling for previous levels of experienced racial discrimination, previous levels of depressive symptoms, the concurrent association between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms, and the link between depressive symptoms and experienced racial discrimination 1 year later (see Figure 1). These models were run using Mplus 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). Model fit was evaluated using the following indicators: chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values above .90 and RMSEA values less than .08 represent acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 1.

Autoregressive cross-lagged structural equation modeling results. Standardized estimates are provided. Cross-lags are in bold. 7 = Grade 7; 8 = Grade 8; 9 = Grade 9; 10 = Grade 10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

To isolate the variance associated with the cross-lag associations and to retain model parsimony, a single equality constraint was imposed across the experienced racial discrimination autoregressions and the depressive symptoms autoregressions. Because stationarity is integral to testing the null hypothesis that the cross-lagged differential is zero (Kenny, 1975), the synchronous correlations between depressive symptoms and experienced racial discrimination at Grades 8, 9, and 10 were constrained to be equal. The correlation for Grade 7 was not constrained, because it was not qualified by Grade 6 associations (i.e., autoregressions, synchronous correlations, and cross-lags); therefore, it was not reasonable to expect the Grade 7 synchronous correlation to be equal to the others. None of the equality constraints significantly reduced model fit.

Results

Hypothesized Base Model

Means and standard deviations of study variables for the total sample and by sex can be found in Table 1, and correlations between study variables by sex can be found in Table 2. Parameter estimates for the pathways included in the base model are provided in Figure 1. All autoregressive pathways and synchronous correlations in the base model were significant and positive. Each of the parameter estimates for the cross-lag pathways from experienced racial discrimination to depressive symptoms 1 year later was significant. None of the parameter estimates for the cross-lag pathways from depressive symptoms to experienced racial discrimination 1 year later was significant. Fit indices suggested that the base model fit was adequate, χ2(327) = 754.29, p < .001; TLI = .89; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .05 (90% confidence interval [0.05, 0.06]). See supplemental materials for parameter estimates and latent racial discrimination variable factor loadings.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables for Total Sample and by Sex

| Total |

Males |

Females |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | Possible range | Observed range | M (SD) | M (SD) | t |

| Racial discrimination | ||||||

| Grade 7 | 1.73 (0.87) | 1–7 | 1.00–5.29 | 1.75 (0.90) | 1.72 (0.85) | 0.38 |

| Grade 8 | 1.78 (0.84) | 1–7 | 1.00–5.57 | 1.79 (0.81) | 1.77 (0.86) | 0.32 |

| Grade 9 | 1.91 (0.92) | 1–7 | 1.00–6.00 | 1.97 (0.94) | 1.83 (0.88) | 1.58 |

| Grade 10 | 1.58 (0.78) | 1–7 | 1.00–5.14 | 1.70 (0.85) | 1.46 (0.69) | 3.19** |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| Grade 7 | 0.63 (0.40) | 0–3 | 0.00–2.62 | 0.60 (0.36) | 0.66 (0.45) | −1.68 |

| Grade 8 | 0.60 (0.40) | 0–3 | 0.00–2.24 | 0.54 (0.34) | 0.66 (0.45) | −3.20*** |

| Grade 9 | 0.62 (0.43) | 0–3 | 0.00–2.43 | 0.60 (0.42) | 0.64 (0.44) | −0.83 |

| Grade 10 | 0.55 (0.41) | 0–3 | 0.00–2.29 | 0.49 (0.40) | 0.61 (0.42) | −3.19** |

Note. M = mean item score. Grade 7: N = 473 for perceived racial discrimination and 474 for depressive symptoms. Grade 8: N = 475 for perceived racial discrimination and 475 for depressive symptoms. Grade 9: N = 465 for perceived racial discrimination and 464 for depressive symptoms. Grade 10: N = 438 for perceived racial discrimination and 438 for depressive symptoms.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed).

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables by Sex

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Racial discrimination (Grade 7) | — | .25*** | .34*** | .26*** | .37*** | .24*** | .33*** | .22** |

| 2. Depressive symptoms (Grade 7) | .27*** | — | .07 | .64*** | .06 | .62*** | −.02 | .44*** |

| 3. Racial discrimination (Grade 8) | .38*** | .19** | — | .19** | .28*** | .22*** | .41*** | .23*** |

| 4. Depressive symptoms (Grade 8) | .11 | .55*** | .23*** | — | .15* | .69*** | .03 | .50*** |

| 5. Racial discrimination (Grade 9) | .27*** | .09 | .42*** | .20** | — | .15* | .49*** | .15* |

| 6. Depressive symptoms (Grade 9) | .19** | .51*** | .18** | .58*** | .18** | — | .08 | .61*** |

| 7. Racial discrimination (Grade 10) | .21** | .10 | .43*** | .13 | .49*** | .25*** | — | .17* |

| 8. Depressive symptoms (Grade 10) | .20** | .40*** | .22*** | .49*** | .23*** | .59*** | .29*** | — |

Note. Correlations for females are above the diagonal; correlations for males are below the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed).

Experienced Racial Discrimination as a Predictor of Subsequent Depressive Symptoms

Examination of the cross-lag associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms 1 year later suggested that experienced racial discrimination predicts subsequent depressive symptoms after controlling for autoregressive, synchronous, and reciprocal cross-lag pathways (see Figure 1). Experienced racial discrimination in grade t was significantly associated with depressive symptoms in grade t + 1 across all 4 years (Grades 7–8: β = 0.08, p < .05; Grades 8–9: β = 0.12, p < .01; Grades 9–10: β = 0.10, p < .05).

Directionality of the Racial Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms Link

None of pathways from depressive symptoms to experienced racial discrimination 1 year later was statistically significant. Formal comparisons of the significant discrimination → depression cross-lags with the nonsignificant depression → racial discrimination cross-lags were not performed, because it could not be concluded with reasonable certainty that nonsignificant parameter estimates were anything other than zero (the null hypothesis; Nickerson, 2000). Thus, there was not sufficient evidence to suggest that depressive symptoms predicted racial discrimination 1 year later across any of the four waves.

Sex as a Moderator of the Association Between Experienced Racial Discrimination and Subsequent Depressive Symptoms

Multiple-group analyses were used to test whether sex moderated the associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. For these analyses, models with the path from experienced racial discrimination to depressive symptoms constrained to be equal for males and females were compared to a model in which the path was freely estimated; each path from experienced racial discrimination to depressive symptoms was constrained in a separate model. The fit of the model with the pathway from Grade 7 experienced racial discrimination to Grade 8 depressive symptoms constrained to be equal for males and females was significantly worse than the freely estimated model, (1) = 8.12, p < .001, indicating moderation by sex. Examination of the freely estimated model revealed the path was significant for females (β = 0.07, p < 0.05) and not significant for males (β= −0.03, p > 0.05). The models constraining paths from Grades 8 and 9 racial discrimination to subsequent depressive symptoms were not significantly different from the freely estimated models, suggesting that sex did not moderate these pathways (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Model Fit Indices for Base Model and Moderation Models

| Model | χ2 (df) | Δχ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base model | 754.29 (327) | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.05 | |

| Base model grouped by sex | 1,380.34 (700) | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.06 | |

| Sex moderation Grades 7–8 | 1,388.46 (701) | 8.12*** (1) | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.06 |

| Sex moderation Grades 8–9 | 1,380.34 (701) | 0.00 (1) | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.06 |

| Sex moderation Grades 9–10 | 1,380.56 (701) | 0.22 (1) | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.06 |

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

p < .001 (two-tailed).

Discussion

Results of this 4-year prospective study confirm and extend cross-sectional (e.g., Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009) and short-term (Gibbons et al., 2004) longitudinal studies linking experienced racial discrimination with depressive symptoms. Findings indicated that for African American adolescents, experienced racial discrimination predicted depressive symptoms, but there was no evidence to suggest that depressive symptoms predicted experienced racial discrimination. Combined with previous literature on adult racial discrimination (e.g., Williams & Mohammed, 2009), the persistence of this predictive association across adolescence suggests that experiencing racial discrimination is a phenomenon that is chronic and detrimental across the life span for African Americans. Importantly, as a function of the statistical controls utilized in this study, respondents’ reports of racial discrimination were not confounded by previous and existing depressive symptoms; thus, the findings separated the stress process and the disease process in showing that racial discrimination predicts depressive symptoms longitudinally for African American adolescents. Of note, this study provides no evidence for theories suggesting that disease states predict or confound the appraisal of race-related stress (Meyer, 2003). Taken together, results of this study provide a strong case for the validity of theoretical models that posit experienced racial discrimination as antecedent to negative psychological outcomes (e.g., Clark et al., 1999).

Results provided partial support for the hypothesis that the link between experienced racial discrimination and later depressive symptoms is stronger for females than males. Females were more susceptible to depressive symptoms as a result of experienced racial discrimination than males early in adolescence, but not later. This finding may reflect changes in the rate and content of experienced racial discrimination for males and females. Research has suggested that African American adult males are faced with more frequent and racialized stereotypes than females, as they are commonly depicted throughout U.S. society as violent and threatening (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). These gendered racial stereotypes may have a more profound effect on depressive symptoms for males as they develop into adults, causing the link between experienced racial discrimination and depression to be similar to that of females, despite females’ greater susceptibility to depressive symptoms (e.g., Dunn & Goodyer, 2006). In addition, there is evidence that male gender roles exacerbate the link between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in adult African Americans (Hammond, 2012).

Strengths and Limitations

By examining multiple alternative causal patterns between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms during early adolescence, the present study informs our understanding of the etiology of depression in African American youth. However, some limitations are worth noting. Participants were drawn from urban, predominantly African American schools, limiting generalizability to African American youth in other settings. Measurements of experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms had different time frames, 1 year and 2 weeks, respectively. This complicates the assumption in cross-lagged analysis that the two constructs are measured simultaneously (Kenny, 1975). In addition, it is possible that the observed experienced racial discrimination–depressive symptoms link could have been caused by a third variable not included in the analyses (e.g., family, neighborhood, or school factors). Participants also reported low levels of experienced racial discrimination, suggesting that the measure used in this study may not tap into common types of racial discrimination experienced by African American adolescents; in fact, recent evidence has suggested that African American adolescents’ reports on popular quantitative measures of experienced racial discrimination are low compared to their qualitative reports (e.g., Berkel et al., 2009). Finally, the model used in this study constrained associations between consecutive measurements of depressive symptoms and experienced racial discrimination to be equal across years. While this aided in model parsimony, there have been no studies, to the authors’ knowledge, that have established that these two constructs have similar stabilities across time.

Future Directions

Past studies have identified areas in which experienced racial discrimination measurement can be improved including using more precise time frames for measurement (e.g., Williams & Mohammed, 2009); employing mixed methods (Berkel et al., 2009), including developmentally appropriate contexts where racial discrimination may be present for adolescents (e.g., Internet; Tynes, Giang, Williams, & Thompson, 2008); and parsing the effects of institutional and interpersonal racial discrimination (Nyborg & Curry, 2003). The nature of associations between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents will be clarified with these improvements in measurement. In addition, future studies should investigate specific processes and coping strategies that attenuate the link between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms; this information will be useful in the design of programs promoting healthy developmental outcomes for African American adolescents. Finally, it will be important to identify mechanisms that lead to sex differences in the link between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American early and late adolescents. Addressing these factors will be key in preventing the stress process initiated by racial discrimination and in reducing the consequent depressive symptoms incurred by African American youth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH057005: Nicholas S. Ialongo, principal investigator [PI]; MH078995: Sharon F. Lambert, PI) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA11796: Nicholas S. Ialongo, PI). We thank the Baltimore City Public Schools for their collaborative efforts and the parents, children, teachers, principals, and school psychologists and social workers who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034703.supp

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd. Author; Washington, DC: 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Carlson GA. Depression Self-Rating Scale: Utility with child psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:491–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.491. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Murry VM, Hurt TR, Chen Y, Brody GH, Simons RL, Gibbons FX. It takes a village: Protecting rural African American youth in the context of racism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9346-z. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Bigler RS. Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development. 2005;76:533–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous TM, Rivas-Drake D, Smalls C, Griffin T, Cogburn C. Gender matters, too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:637–654. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello J, Angold A. Child-hood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. doi:10.1001/ archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. doi:10.1001/ archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn V, Goodyer IM. Longitudinal investigation into child-hood and adolescenceonset depression: Psychiatric outcome in early adulthood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:216–222. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.3.216. doi:10.1192/ bjp.188.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. doi:10.1023/A:1026455906512. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, García HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi:10.2307/1131600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Cunningham JA. The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:532–543. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP. Taking it like a man: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S232–S241. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. The Racism and Life Experiences Scales (RaLES-Revised) Culver City, CA: 1997. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. doi:10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Kellam G, Poduska J. Manual for the Baltimore How I Feel. Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore, MD: 1999. Tech. Rep. No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Werthamer L, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Wang S, Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:599–641. doi: 10.1023/A:1022137920532. doi:10.1023/A:1022137920532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Cross-lagged panel correlation: A test for spuriousness. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:887–903. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.82.6.887. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory: A self-rated depression scale for school-age youngsters. University of Pittsburgh; 1983. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. doi:10.2105/AJPH.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:262–265. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.262. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide 6. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson RS. Null hypothesis significance testing: A review of an old and continuing controversy. Psychological Methods. 2000;5:241–301. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.2.241. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.5.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:173–176. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00142. [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg VM, Curry JF. The impact of perceived racism: Psychological symptoms among African American boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:258–266. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_11. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Szalacha LA, Bernstein BA, García Coll C. Perceptions of racism in children and youth (PRaCY): Properties of a self-report instrument for research on children’s health and development. Ethnicity & Health. 2010;15:33–46. doi: 10.1080/13557850903383196. doi:10.1080/13557850903383196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. An intersectional approach for understanding perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(5):1372–1379. doi: 10.1037/a0019869. doi:10.1037/a0019869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechrist GB, Swim JK, Mark MM. Mood as information in making attributions to discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:524–531. doi: 10.1177/0146167202250922. doi:10.1177/0146167202250922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187–216. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummund H, Stewart E, Brody GH, Cutrona C. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. doi:10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, Giang MT, Williams DR, Thompson GN. Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.021. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.