Abstract

Objective

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a cognitive screening instrument growing in popularity, but few studies have conducted psychometric item analyses or attempted to develop abbreviated forms. We sought to derive and validate a short form MoCA (SF;MoCA) and compare its classification accuracy to the standard MoCA and MMSE in mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer disease (AD), and normal aging.

Methods

408 subjects (MCI n=169, AD n=87, normal n=152) were randomly divided into derivation and validation samples. Item analysis in the derivation sample identified most sensitive MoCA items. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to develop cutoff scores and evaluate the classification accuracy of the SF;MoCA, standard MoCA, and MMSE. Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) analyses and comparison of ROC curves were used to compare classification accuracy of the three measures.

Results

Serial subtraction (Cramer's V=.408), delayed recall (Cramer's V=.702), and orientation items (Cramer's V=.832) were included in the SF;MoCA based on largest effect sizes in item analyses. Results revealed 72.6% classification accuracy of the SF; MoCA, compared with 71.9% for the standard MoCA and 67.4% for the MMSE. Results of NRI analyses and ROC curve comparisons revealed that classification accuracy of the SF;MoCA was comparable to the standard version and generally superior to the MMSE.

Conclusions

Findings suggest the SF;MoCA could be an effective brief tool in detecting cognitive impairment.

Keywords: short form, Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, cognitive screening, Montreal Cognitive Assessment

Introduction

As early detection of dementia becomes increasingly important, there is a growing need for quick and effective cognitive screening measures. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Nasreddine et al., 2005) was developed as an alternative to the popular Mini;Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein & McHugh, 1975) has shown improved sensitivity to mild cognitive impairment (MCI; Markwick, Zamboni, & de Jager, 2012; Smith, Gildeh, & Holmes, 2007). Although the MMSE and MoCA are relatively brief (10;15 minutes administration time), their use in routine healthcare visits may still be limited due to time constraints (Iliffe et al., 2009; Tangalos et al., 1996). Therefore, many clinicians have a limited ability to quickly screen for cognitive impairment and may have difficulty determining when to refer for further evaluation when cognitive concerns are raised.

Abbreviated forms of the MMSE have been developed to address these issues by discarding less useful items and retaining those with higher discriminative value while maintaining classification accuracy. Three word recall and orientation items on the MMSE are best able to discriminate demented from healthy older adults (Braekhus, Laake, & Engedal, 1992; Galasko et al., 1990), and many abbreviated forms of the MMSE and other cognitive screening tests have included these items to maintain sensitivity (e.g. Schultz-Larsen, Lomholt, & Kreiner, 2007). Haubois et al. (2011) created a 6;point MMSE short form including only immediate and delayed recall items which showed similar sensitivity (89.5% versus 90.0%) and increased specificity (85.4% versus 75.5%) compared to the standard MMSE when screening for dementia. Despite inherent performance variability of 3;word recall (Cullum, Thompson & Smernoff, 1993), the importance of delayed recall tasks is also demonstrated in studies which show that the Mini;Cog, comprised of 3;word recall and a clock drawing task, is effective in detecting dementia (Borson, Scanlan, Chen, & Ganguli, 2003; Borson, Scanlan, Watanabe, Tu, & Lessig, 2005).

The MoCA is growing in popularity as a brief cognitive screening measure that is freely available (www.mocatest.org). In addition to the advantage of increased sensitivity to MCI, the MoCA is available in multiple languages and several forms are available in English for the purposes of repeat evaluations. Despite these advantages, there have been limited psychometric analyses of MoCA items and few attempts to develop abbreviated versions. An abbreviated MoCA composed of orientation items, immediate and delayed recall items, and a phonemic fluency task was proposed by the neuropsychology working group of the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke – Canadian Stroke Network Vascular Cognitive Impairment (NINDS;CSN VCI) for cognitive screening of patients with vascular disease (Hachinski et al., 2006). Freitas, Simões, Alves, Vicente, and Santana (2012) found it to be psychometrically sound and able to discriminate 34 patients with vascular dementia from 34 controls (area under the curve = .936). However, this is the only publication to date that examines the classification accuracy of an abbreviated MoCA, and is limited by its primary focus on a relatively small sample of patients with vascular dementia.

Given that Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and is often preceded by MCI, an abbreviated MoCA effective in identifying and discriminating these populations would be useful. An abbreviated MoCA would also be valuable in addressing the criticisms of lengthy administration time in some settings and the inclusion of items that do not contribute to overall sensitivity. The purpose of the current study was to derive a short;form MoCA (SF;MoCA) and compare its classification accuracy to the standard MoCA and MMSE in distinguishing patients with MCI, AD, and cognitively normal controls (NC). We hypothesized that orientation and recall items would best distinguish between diagnostic groups given that similar items have demonstrated utility and are commonly included in cognitive screening tools (e.g., Borson, Scanlan, Brush, Vitaliano, & Dokmak, 2000; Hachinski et al., 2006; Haubois et al., 2011).

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of 408 subjects (169 MCI, 87 AD, 152 controls) who underwent neurodiagnostic evaluation at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Alzheimer's Disease Center between January 2012 and February 2014 in compliance with institutional regulations. Diagnoses of possible and probable AD were made according to NINCDS/ADRDA criteria and MCI was diagnosed using Petersen criteria (Petersen, 2004) based upon multidisciplinary consensus review of neurologic, psychiatric, and neuropsychological data, in addition to patient; and informant;based reports. The MMSE was administered as part of the uniform data set of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, and the MoCA was added to our center's evaluations in 2012 to explore its utility. MMSE scores within the AD group ranged from 9 to 29 with an overall mean of 21.2, reflecting a mild level of dementia.

The total sample (76.7% Caucasian) was divided into two groups: 1) the derivation sample included a random selection of approximately 75% of cases (126 MCI, 67 AD, 124 NC) via the “select cases” function in SPSS 21, and 2) the remaining cases (43 MCI, 20 AD, 28 NC) comprised the validation sample. Demographic characteristics and test scores for each sample are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Derivation and Validation Samples

| NC | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derivation Sample | |||

| n | 124 | 126 | 67 |

| Age | 69.6 (7.9) | 69.4 (7.7) | 74.4 (8.1) |

| Education | 15.3 (2.6) | 14.5 (2.8) | 15.2 (2.7) |

| % Female | 67 | 52 | 37 |

| % Caucasian | 86.3 | 63.5 | 83.6 |

| SF-MoCA | 12.7 (1.2) | 10.8 (1.9) | 4.7 (3.3) |

| MoCA | 27.0 (2.1) | 23.0 (3.5) | 14.1 (6.0) |

| MMSE | 28.9 (1.1) | 27.7 (1.8) | 20.4 (4.9) |

| Validation Sample | |||

| n | 28 | 43 | 20 |

| Age | 70.0 (7.0) | 70.2 (6.1) | 74.7 (7.9) |

| Education | 16.2 (2.1) | 15.2 (3.0) | 15.3 (2.5) |

| % Female | 46 | 56 | 35 |

| % Caucasian | 92.9 | 65.1 | 80.0 |

| SF-MoCA | 12.7 (1.6) | 11.3 (1.6) | 7.1 (2.9) |

| MoCA | 26.7 (2.2) | 24.2 (2.8) | 17.0 (5.7) |

| MMSE | 29.0 (0.8) | 27.6 (2.3) | 23.8 (3.5) |

Note. NC = Normal Control; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD = Alzheimer Disease; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SF-MoCA = Short-Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination. Data are presented as means (standard deviation).

Statistical Analyses

Derivation sample

Item analyses of individual MoCA items were used to determine which items best differentiated the three diagnostic groups. Performance of each item was evaluated using Cramer's V with the expectation that the best items would have the largest effect sizes. The three items with the greatest effect sizes based on item analyses were selected for the SF;MoCA. One; way ANOVA was used as a preliminary test to examine differences between the groups on the SF;MoCA. To allow comparison of effect sizes across measures, one;way ANOVAs of the standard MoCA and MMSE were also conducted.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to evaluate and compare the sensitivity and specificity of the SF;MoCA, standard MoCA, and the MMSE, first in the detection of cognitive impairment. Specifically, we used these analyses to examine the classification accuracy of each measure in distinguishing the NC group from a combined group of MCI + AD subjects (“cognitively impaired” group). We also used ROC analyses to examine the accuracy of each measure in discriminating the AD group from the remainder of the sample for the purpose of cutoff score development. Combining diagnostic groups allowed us to use the entire sample with each ROC analysis and develop cutoff scores for both MCI and AD groups. Cutoff scores were developed for each measure based on sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and the perpendicular distance between the selected point and the line of equality (Riffenburgh, 2006). ROC curves for the SF;MoCA were compared to the MMSE using a method developed by Hanley and McNeil (1983). Comparisons were made between the standard and short forms of the MoCA in the accurate detection of cognitive impairment using Net Reclassification Improvement (NRI) analyses (Pencina, D'Agostino, D'Agostino, and Vasan, 2007), which quantify differences in classification rates between two measures or models. We employed this method to compare the standard and short forms of the MoCA instead of ROC comparisons due to overlap of items and increased statistical power of this analysis.

Validation sample

Similar analyses were conducted in the validation sample to support initial findings. ROC analyses were conducted for each measure to examine accuracy in distinguishing the NC group from the cognitively impaired group. The SF;MoCA and MMSE were compared in the accurate detection of cognitive impairment via statistical comparison of ROC curves, while this comparison was made between the standard and abbreviated MoCA versions using NRI analyses. Classification accuracy of cut scores selected in the derivation sample was evaluated by correct predictions via crosstabs.

Additional analyses

To further explore the discrimination of groups using the SF;MoCA, we conducted additional analyses in both samples. ROC analyses were performed using the predictions from logistic regression in models that included the SF;MoCA and adjusted for age, sex, and education. The added predictive value of the risk;adjusted models was evaluated using NRI analyses. This method was used to determine if the inclusion of demographic measures into the final ROC models would significantly improve discriminative value.

ROC analyses were used in the validation sample to test the classification accuracy of each measure in discriminating the AD group from the remainder of the sample. Comparisons of ROC curves were conducted to compare the SF;MoCA and MMSE in distinguishing these groups in both samples. Classification accuracy of the standard and SF;MoCA were compared in discriminating these groups using NRI analyses in both samples. Assumptions for all analyses were reviewed. In cases where assumptions were violated, we compared the findings of non; parametric tests to the parametric tests and in all cases the results were similar; we have reported the results of the parametric tests.

Results

Derivation Sample

Item analysis of individual MoCA items in the derivation sample revealed that serial subtraction (Cramer's V = .338) and delayed recall (Cramer's V = .489) were the best individual items at distinguishing between the NC and MCI groups. In discriminating between MCI and AD, item analyses showed that serial subtraction (Cramer's V = .408), delayed recall (Cramer's V = .702), and orientation items (Cramer's V = .832) best distinguished groups. These three items were selected for the SF;MoCA due to larger effect sizes (Cramer's V > .300) relative to other items and, therefore, greater accuracy in effectively distinguishing the three diagnostic groups. The inclusion of these items resulted in a maximum SF;MoCA score of 14. Item analyses when differentiating between NC and AD groups were not used in determining most sensitive items due to limited variability among effect sizes for items.

The SF;MoCA performed well in distinguishing the clinical samples. One;way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference between the three groups in terms of MMSE scores (F (2, 313) = 246.2; p < .001), with a large effect size (ηp2 = .611). Similar findings were observed for standard MoCA scores (F (2, 314) = 254.5; p < .001; ηp2= .618). Slightly larger differences between groups were seen on the SF;MoCA relative to the other screening measures (F (2, 314) = 333.04; p < .001; ηp2 = .680).

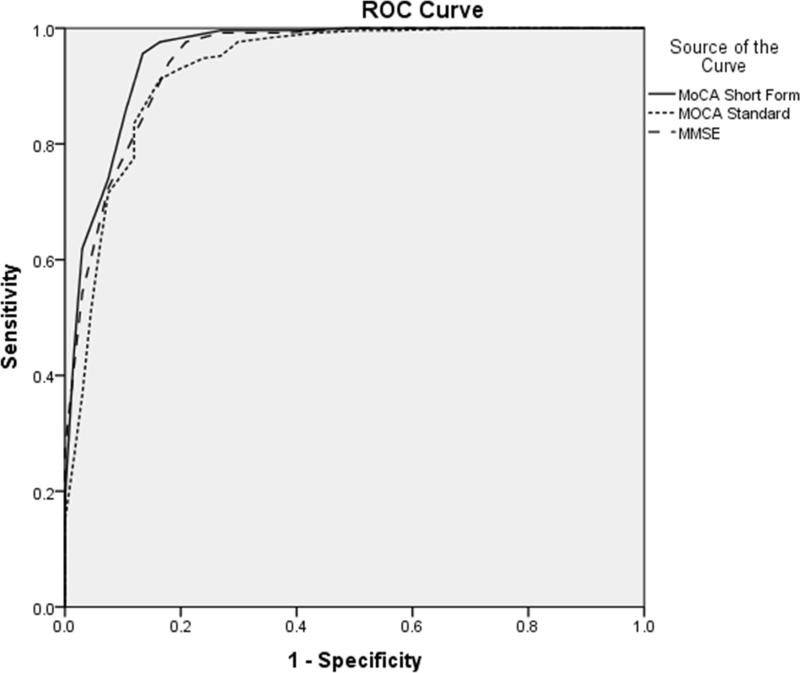

In ROC analyses, the abbreviated and standard forms of the MoCA showed similar areas under the curve (AUC) when distinguishing the NC group from the cognitively impaired group as a whole (AUC = .86 vs .88). The SF;MoCA also demonstrated a similar AUC to the standard MoCA when differentiating patients with AD from the rest of the sample (AUC = .96 vs .93). The SF;MoCA showed a slightly larger AUC than the MMSE when differentiating controls from those with cognitive impairment (AUC = .86 vs .79). The SF;MoCA demonstrated a similar AUC to the MMSE when distinguishing patients with AD from the remainder of the sample (AUC = .96 vs .95). Figures 1 and 2 display ROC curves for each measure in the derivation sample.

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for the SF-MoCA, Standard MoCA, and MMSE in differentiating controls from the cognitively impaired group (MCI+AD) in the derivation sample. MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD = Alzheimer Disease; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SF-MoCA = Short-Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination.

Figure 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for the SF-MoCA, Standard MoCA, and MMSE in differentiating AD from the remainder of the derivation sample (NC+MCI). NC = Normal Control; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD = Alzheimer Disease; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SF-MoCA = Short-Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination.

A significant difference was detected between ROC curves of the SF;MoCA and the MMSE when distinguishing between healthy controls and the cognitively impaired group (z = 3.13; p < .01), with the SF;MoCA outperforming the MMSE. NRI analyses showed no significant differences between the accuracy of the standard and short forms of the MoCA when distinguishing between these groups (NRI = 0.02; p = .73).

ROC analyses revealed an optimal cutoff score of <12 on the SF;MoCA to detect MCI and a cut point of <9 to detect AD. These cutoff scores resulted in an overall classification accuracy of 72.6% when classifying participants as NC, MCI, or AD. Cut scores of <26 and <20 on the standard MoCA were used to classify MCI and AD, respectively. The standard MoCA exhibited a classification accuracy of 71.9% when using these selected cutoff scores. Finally, classification accuracy of the MMSE was found to be 67.4% when using cut points of <29 and <25 to detect MCI and AD.

Validation Sample

Results in the validation sample were similar to findings in the derivation sample. The effect sizes from one;way ANOVAs revealed largest group differences on the SF;MoCA compared to the other measures (F (2, 88) = 51.9; p < .001; ηp2 = .541). The abbreviated and standard forms of the MoCA showed highly similar AUCs when differentiating healthy controls from the combined cognitively impaired group (AUC = .81 vs .83). Similar to results in the derivation sample, the AUC for the SF;MoCA was slightly larger than the MMSE when discriminating between these groups (AUC = .81 vs .78). Figure 3 displays ROC curves for each measure discriminating controls from cognitively impaired groups in the validation sample.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for the SF-MoCA, Standard MoCA, and MMSE in differentiating controls from the cognitively impaired group (MCI+AD) in the validation sample. MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD = Alzheimer Disease; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SF-MoCA = Short-Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination.

When using cutoff scores selected in the derivation sample, the SF;MoCA correctly classified 61.5% of participants as NC, MCI, or AD in the validation sample. The standard MoCA exhibited similar classification accuracy, as derived cut scores resulted in 63.7% total accuracy. Finally, the MMSE correctly classified 57.8% of participants when using cutoff scores selected in the derivation sample. Table 2 presents the classification accuracy of each measure using the derived cut points.

Table 2.

Cutoff Scores and Diagnostic Accuracy of Each Measure in Derivation and Validation Samples

| Total Accuracy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | MCI cutoff | AD cutoff | Derivation | Validation |

| SF-MoCA | < 12/14 | < 9/14 | 72.6% | 61.5% |

| MoCA | < 26/30 | < 20/30 | 71.9% | 63.7% |

| MMSE | 29/30 | < 25/30 | 67.4% | 57.8% |

Note. MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD = Alzheimer Disease; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SF-MoCA = Short-Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination. Total accuracy is based on correct classification of participants as NC, MCI, or AD.

NRI analyses in the validation sample revealed no significant differences in classification accuracy of the standard and SF; MoCA when differentiating controls from the cognitively impaired group (NRI = 0.04; p = .68). Similarly, no significant difference was found when comparing ROC curves of the SF;MoCA and MMSE when differentiating these groups (z = 0.76; p = .45).

Additional Analyses

In the derivation sample, NRI analyses revealed that accuracy was not significantly improved when the ROC models for the SF;MoCA accounted for age, sex, and education when differentiating controls from the cognitively impaired group (NRI = .02; p = .29) or AD from the rest of the sample (NRI = .03; p = .21). In light of these results, demographic variables were not incorporated into the final ROC models. Additional NRI analyses showed no significant differences between the accuracy of the standard and short forms of the MoCA when distinguishing AD from the rest of the derivation sample (NRI = ;0.03; p = .42). Comparison of ROC curves revealed no significant difference between the SF;MoCA and MMSE when differentiating between these groups (z = 0.70; p = .48).

In terms of differentiating patients with AD from the remainder of the validation sample, the standard and SF; MoCA showed highly similar AUCs (AUC = .93 vs .91). Similar to results in the derivation sample, the AUC for the SF;MoCA was slightly larger than the MMSE when discriminating between these groups (AUC = .93 vs .88). These ROC analyses are depicted in Figure 4. NRI analyses revealed no significant differences in the classification accuracy of the standard and short forms of the MoCA when discriminating patients with AD from the rest of the validation sample (NRI = ;0.10; p = .43). Finally, no significant difference was detected when comparing ROC curves of the SF;MoCA and MMSE when distinguishing between these groups (z = 1.48; p = .14).

Figure 4.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for the SF-MoCA, Standard MoCA, and MMSE in differentiating AD from the remainder of the validation sample (NC+MCI). NC = Normal Control; MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD = Alzheimer Disease; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SF-MoCA = Short-Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination.

Discussion

Brief cognitive screening instruments are important in both clinical and research settings, particularly as there is a push to include cognitive checkups as part of healthcare wellness visits (Borson et al., 2007; Brayne, Fox, & Boustani, 2007). This was reinforced by the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which requires providers to “detect any cognitive impairment” as part of the annual wellness visit for Medicare recipients. In addition to the limitation of relatively low sensitivity to subtle cognitive impairment, most current cognitive screening examinations are criticized for relatively lengthy administration times and include test items that do not enhance sensitivity. To address these issues, we sought to develop a short form of the MoCA which could decrease administration time while maintaining classification accuracy.

Orientation, word recall, and serial subtraction items were the best discriminators between diagnostic groups and were included in the SF;MoCA. We expected orientation and recall items to distinguish groups with higher accuracy than other items due to their sensitivity to cognitive impairment and inclusion in other brief cognitive screening instruments (e.g., Borson et al., 2000; Folstein et al., 1975; Hachinski et al., 2006; Haubois et al., 2011). While short forms of common cognitive screening tests have not typically included a serial subtraction component, this task is often used in mental status examinations (e.g., Strub & Black, 1985) and added to discriminability in the current sample. These results are consistent with an item analysis of the MMSE by Schultz-Larsen, Kreiner, and Lomholt (2007) which found that demented participants most commonly lost points on “orientation to time and place,” “three;object recall,” and “serial sevens.”

The SF;MoCA consists of orientation, recall, and serial subtraction items, resulting in a maximum score of 14 points. The groups showed statistically significant differences in scores on each of the three screening measures examined, with largest differences observed on the SF; MoCA in both the derivation and validation samples. The SF;MoCA showed larger AUCs than the MMSE in both samples when discriminating healthy controls from those with cognitive impairment, as well as patients with AD from the rest of the sample. Moreover, comparison of AUCs in the derivation sample using the method of Hanley and McNeil (1983) revealed a significant difference between the SF;MoCA and MMSE when differentiating healthy controls from those with cognitive impairment. Although this finding was not replicated in the validation sample, results of these ROC analyses support the ability of the SF;MoCA to distinguish between diagnostic groups with equal or better accuracy than the MMSE. These findings were further corroborated following the development of cutoff scores for each measure. Using cut points of <12 for MCI and <9 for AD, the SF;MoCA had an overall classification accuracy of 72.6% in the derivation sample and 61.5% in the validation sample. In contrast, the MMSE showed a classification accuracy of 67.4% in the derivation sample and 57.8% in the validation sample using cutoff scores of <29 for MCI and <25 for AD. It should be noted that our MMSE cutoff of <25 to detect AD is 1 point higher than the traditional cut score of <24 most commonly cited in the literature to detect dementia, although this slightly higher score is not surprising given the above;average education of our groups. Overall, the classification accuracy of the SF; MoCA was superior to the MMSE in the current sample, as evidenced by better performance in each of the analyses conducted. Given that the MMSE has been widely used and even considered the “gold standard” of cognitive screening instruments (Boustani, Peterson, Hanson, Harris, & Lohr, 2003; Landi et al., 2000), these results support the use of the SF;MoCA for cognitive screening.

The SF;MoCA also performed well when compared to the standard MoCA. In both the derivation and validation samples, the SF;MoCA showed a slightly larger AUC than the standard MoCA when distinguishing patients with AD from the rest of the sample. However, AUCs of the standard MoCA in both samples were slightly larger than the SF;MoCA when discriminating controls from those with cognitive impairment. Using cutoff scores of <26 and <20 to classify MCI and AD, the standard MoCA demonstrated classification accuracies of 71.9% and 63.7% in the derivation and validation samples, respectively, compared to 72.6% and 61.5% for the SF; MoCA. It is also worth noting that the cut scores derived for the standard MoCA in the current study are consistent with the cutoff score of <26 originally proposed by Nasreddine et al. (2005) to detect cognitive impairment. NRI analyses showed that differences in the classification accuracy of these measures in each sample were small, non;significant, and unlikely to be clinically relevant.

These findings furthermore suggest that some MoCA items do not add appreciably to the clinical sensitivity of the standard version and that similar classification rates can be achieved with an abbreviated version. This is not surprising given that not all items on most omnibus cognitive screening instruments contribute to sensitivity. Rossetti, Lacritz, Cullum, and Weiner (2011) found that some MoCA items were useful in detecting cognitive impairment, while other items were rarely missed. Consequently, the SF;MoCA may be a comparably accurate, more efficient alternative to the standard form.

One strength of this study is the use of statistically;based selection criteria for items in the SF;MoCA. This contrasts with the techniques involved in developing many cognitive screening instruments wherein items are selected based on clinical judgment and/or loosely on prior research (e.g., Folstein et al., 1975; Hachinski et al., 2006; Nasreddine et al., 2005). Given that we employed a statistically;based method to develop the SF;MoCA, this specific combination of items should maximally distinguish similar diagnostic groups, although replication in larger and more heterogeneous samples will be needed to verify this. Another strength of this study involves the validation of results found in the derivation sample. Whereas replication of our findings in future studies would provide additional support for our conclusions, we were able to demonstrate that our findings generalized to a separate sample. Although classification accuracy of the SF;MoCA was decreased in the validation sample, this is a common result of testing a model that optimally fits the original data (Kohavi, 1995). Furthermore, the classification accuracy of the MMSE and standard MoCA were also reduced in the validation sample, suggesting that this finding was not specific to the SF;MoCA.

This study has several limitations. First, the education level of our overall sample was relatively high, and therefore the results may not generalize to individuals with lower levels of education. Additionally, as with the development of many abbreviated test versions, the SF; MoCA was derived from administration of the standard version. Hence, the short form was not administered as a unique test, and it is possible that the changes in administration timing might influence performance on some items. Along these same lines, a standard procedure for the administration of the SF;MoCA has not been addressed, and total administration time has not yet been determined.

Overall, the classification accuracy of the SF;MoCA was comparable to the standard version and generally superior to the MMSE. This suggests that the SF;MoCA could be an effective and efficient brief tool for raising suspicion of or detecting gross cognitive impairment, although the results of any brief cognitive screening test should not be interpreted in isolation or used to make a clinical diagnosis. Directions for future research include the development of a standardized protocol for administration of the SF;MoCA and evaluation of its utility and sensitivity in various clinical settings and populations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number P30Ag12300;19).

Footnotes

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The mini-cog: a cognitive 'vital signs' measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–1027. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::aid-gps234>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(10):1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan J, Hummel J, Gibbs K, Lessig M, Zuhr E. Implementing routine cognitive screening of older adults in primary care: process and impact on physician behavior. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(6):811–817. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu SP, Lessig M. Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini-Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(5):871–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(11):927–937. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braekhus A, Laake K, Engedal K. The Mini-Mental State Examination: identifying the most efficient variables for detecting cognitive impairment in the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40(11):1139–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayne C, Fox C, Boustani M. Dementia screening in primary care: Is it time?. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(20):2409–2411. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum CM, Thompson LL, Smernoff EN. Three word recall as a measure of memory. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1993;15(2):321–329. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas S, Simões MR, Alves L, Vicente M, Santana I. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): validation study for vascular dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18(6):1031–1040. doi: 10.1017/S135561771200077X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D, Klauber MR, Hofstetter CR, Salmon DP, Lasker B, Thal LJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination in the early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Archives of Neurology. 1990;47(1):49–52. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530010061020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC, Breteler MM, Nyenhuis DL, Black SE, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Canadian stroke network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke. 2006;37(9):2220–2241. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000237236.88823.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148(3):839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubois G, Annweiler C, Launay C, Fantino B, de Decker L, Allali G, et al. Development of a short form of Mini-Mental State Examination for the screening of dementia in older adults with a memory complaint: a case control study. BMC Geriatrics. 2011;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliffe S, Robinson L, Brayne C, Goodman C, Rait G, Manthorpe J, et al. Primary care and dementia: 1. diagnosis, screening and disclosure. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;24(9):895–901. doi: 10.1002/gps.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 1995;14(2):1137–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Landi F, Tua E, Onder G, Carrara B, Sgadari A, Rinaldi C, et al. Minimum data set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the community. Medical Care. 2000;38(12):1184–1190. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwick A, Zamboni G, de Jager CA. Profiles of cognitive subtest impairment in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a research cohort with normal Mini- Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2012;34(7):750–757. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.672966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(2):157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffenburgh RH. Statistics in medicine. Elsevier Inc.; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Cullum CM, Weiner MF. Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1272–1275. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230208a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Larsen K, Kreiner S, Lomholt RK. Mini-Mental Status Examination: mixed Rasch model item analysis derived two different cognitive dimensions of the MMSE. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(3):268–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Larsen K, Lomholt RK, Kreiner S. Mini-Mental Status Examination: a short form of MMSE was as accurate as the original MMSE in predicting dementia. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Gildeh N, Holmes C. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: validity and utility in a memory clinic setting. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(5):329–332. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strub RL, Black FW. The mental status examination in neurology. FA Davis Company; Philidelphia, PA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tangalos EG, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC, Kokmen E, Kurland LT, et al. The Mini-Mental State Examination in general medical practice: clinical utility and acceptance. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1996;71(9):829–837. doi: 10.4065/71.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]