Abstract

Objective:

To determine the frequency and nature of leptomeningeal contrast enhancement in multiple sclerosis (MS) via in vivo 3-tesla postcontrast T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI and 7-tesla postmortem MRI–pathology correlation.

Methods:

Brain MRI, using the postcontrast T2-weighted, FLAIR technique, was prospectively collected in 299 MS cases and 37 age-matched neurologically healthy controls. Expert raters evaluated focal gadolinium enhancement in the leptomeningeal compartment. Two progressive MS cases came to autopsy after in vivo MRI characterization. Pathologic and immunohistochemical examination assessed the association of enhancement with leptomeningeal inflammation and adjacent cortical demyelination.

Results:

Focal contrast enhancement was detected in the leptomeningeal compartment in 74 of 299 MS cases (25%) vs 1 of 37 neurologically healthy controls (2.7%; p = 0.001). Enhancement was nearly twice as frequent (p = 0.009) in progressive MS (39/118 cases, 33%) as in relapsing-remitting MS (35/181, 19%). Enhancing foci generally remained stable throughout the evaluation period (up to 5.5 years). Pathology showed perivascular lymphocytic and mononuclear infiltration in the enhancing areas in association with flanking subpial cortical demyelination.

Conclusion:

Leptomeningeal contrast enhancement occurs frequently in MS and is a noninvasive, in vivo marker of inflammation and associated subpial demyelination. It might therefore enable testing of new treatments aimed at eliminating this inflammation and potentially arresting progressive MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic immune-mediated disorder of the CNS. Its pathologic hallmark—the focal, demyelinated, white matter lesion—is well visualized by in vivo MRI. However, such lesions do not capture the full spectrum of disease, and their number and volume fail to explain the extensive clinical variability that is frequently observed.1 Most important, the disease's progressive phase, in which disability relentlessly accumulates without discrete relapses, often occurs independently of white matter lesion accumulation, suggesting that distinct and poorly captured processes are at play. Aside from volume measurements that generally detect irreversible tissue loss and thus represent a late marker of disease, imaging has so far failed to identify early pathophysiologic processes that precede neuroaxonal pathology in the cortex, a possible substrate of progressive MS.2

A candidate area where persistent inflammation may result in neurodegeneration is the leptomeninges. Indeed, although sustained inflammation within the CNS is detectable as mild lymphocytic pleocytosis, oligoclonal immunoglobulin G bands, and elevated immunoglobulin G within the CSF in almost all MS cases (approximately 95%),3 the pathologic correlate of this inflammation has only recently been recognized. A spectrum of leptomeningeal pathology, with variable degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration, can be observed in biopsies at the time of clinical presentation4 and postmortem.5–9 Clusters of leptomeningeal inflammatory cells that persist over long periods of time may sustain an intrathecal myelin-specific immunologic response and so contribute directly to subpial cortical demyelination and neurodegeneration.4–9 For the most part, inflammatory cell clusters in the leptomeningeal compartment are quite small, far below the millimeter-scale spatial resolution of in vivo MRI.

Inflammation within new white matter lesions in MS is linked to signal enhancement on T1-weighted MRI scans performed after IV injection of a gadolinium-based contrast agent, indicating an abnormally permeable blood-brain barrier.10 In clinical trials and clinical practice, the incidence and number of contrast-enhancing white matter lesions are useful markers for efficacy of anti-inflammatory medications.11 However, imaging leptomeningeal inflammation has proved difficult. Meningeal blood vessels are ubiquitous, enhance avidly with gadolinium on T1-weighted images, and are therefore difficult to distinguish from inflammatory foci. In addition, contrast material leaking into inflammatory foci near the brain surface might mix freely with CSF and thus fail to attain sufficient concentration to be visualized on MRI.

Gadolinium contrast–enhanced, T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) MRI is considered as much as 10-fold more sensitive than T1-weighted imaging for detecting low concentrations of contrast in CSF,12 facilitating imaging-based detection of abnormalities in the leptomeningeal compartment (referred to here, for simplicity, as “leptomeninges”) in other diseases such as leptomeningeal carcinomatosis and infectious meningitis.13–18 In MS, postcontrast T2-FLAIR offers outstanding detection of contrast enhancement within white matter lesions,19,20 but leptomeningeal contrast enhancement has not been investigated. We therefore prospectively acquired these data on all eligible patients seen at our center from late 2009. In this report, we describe the prevalence, distribution, and clinical and laboratory associations of leptomeningeal enhancement in this clinic population. We also describe the histopathologic correlates of in vivo leptomeningeal enhancement, and the spatial relationship between leptomeningeal enhancement and demyelinated cortical lesions, in the formalin-fixed brains of 2 patients with progressive MS.

METHODS

In vivo clinical and radiologic assessment.

Imaging, laboratory, and clinical data were collected with institutional review board approval and after written informed consent. Inclusion criteria were the following: age 18 years or older, clinical diagnosis of MS21 or neurologically healthy, and availability of a 3-tesla (T), 3-dimensional T2-FLAIR scan performed at least 10 minutes after IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast material. For participants with multiple scans obtained during the study period, all scans were reviewed and analyzed in one batch.

MRI was obtained on 2 scanners. Briefly, T2-FLAIR scans followed an IV injection of a single dose (0.1 mmol/kg) of gadolinium-based contrast material. Precontrast T2-FLAIR was available in 46% of cases. MRI sequence details are provided in table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org.

Leptomeningeal enhancement was defined as signal intensity within the subarachnoid space that was substantially greater than that of brain parenchyma and brighter on postcontrast scans than on precontrast scans (when available). High-signal regions adjacent to dural venous sinuses, basal meninges, and large subarachnoid veins were excluded a priori, because we found in preliminary work that these were frequently present on precontrast scans, including in healthy individuals. Postcontrast T1-weighted images were available and evaluated in 100% of cases. Images were reviewed, using standard clinical image-viewing software, in the sagittal plane of the original acquisition and in coronal and axial reformations. Sliding 10-mm maximum intensity projections were also evaluated in at least 2 planes.

Two experienced observers (an attending neuroradiologist with 10 years' experience in MS imaging and a neurologist, currently a resident in radiology, with 9 years' experience), who were masked to clinical and laboratory data, separately evaluated all scans for the presence of leptomeningeal enhancement. Because the initial interrater agreement was moderate (κ = 0.53), discrepancies were adjudicated by consensus. In the rare cases with residual ambiguity, a third attending neuroradiologist with 17 years' experience made a final determination. When present, leptomeningeal enhancement was classified according to location (within a sulcus, overlying the brain convexity, along a dural fissure, or traversing several of these areas), shape (nodular, linear, or plate-like), number of foci, associated enhancement on postcontrast T1-weighted images, and presence or absence of contrast-enhancing white matter lesions anywhere in the brain. Subpial cortical lesions were not assessed in vivo because of their poor detectability at 3T.22

Brain structure segmentation was obtained using Lesion-TOADS and SPECTRE software, as previously described.23 Volumes of white matter lesions, brain, and cerebral cortex, the last 2 normalized to the intracranial volume, were recorded.

Statistical comparisons were made using Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher exact tests, as well as logistic regression models, and p values are reported directly without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Neuropathologic evaluation.

Neuropathologic evaluation focused on the brain of 2 progressive MS cases with a total of 3 stable foci of leptomeningeal enhancement that had been imaged repeatedly in vivo. Detailed clinical and radiologic histories are available in appendix e-1. Accurate registration of in vivo MRI to pathology was achieved via 7T MRI of the fixed brains and subsequent gross sectioning with an individualized, MRI-designed, 3D-printed cutting box.24 For comparison, a block of tissue in the left temporal lobe from the first patient was selected for the presence of extensive cortical pathology, as seen on postmortem MRI, but absence of in vivo leptomeningeal enhancement. Formalin-fixed, 10-μm cryosections or paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin and Luxol fast blue/periodic acid–Schiff and compared with MRI. Immunohistochemical analysis for myelin proteolipid protein, CD45, CD68, CD3, and CD20 was performed on representative slides. See appendix (table e-2) for further details.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study received approval from the institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent. Before death of the 2 patients with progressive MS, the next of kin provided written informed consent for brain autopsy and use of material and clinical information for research purposes.

RESULTS

In vivo clinical and radiologic results.

Data from 299 consecutive MS cases and 37 age-matched neurologically healthy controls were obtained between October 2009 and December 2013 and are included in this report. Population characteristics are described in table 1. Healthy control cases were derived from a variety of sources: 9 healthy volunteers, 19 healthy first-degree relatives of MS cases, and 9 healthy individuals asymptomatically infected with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I.

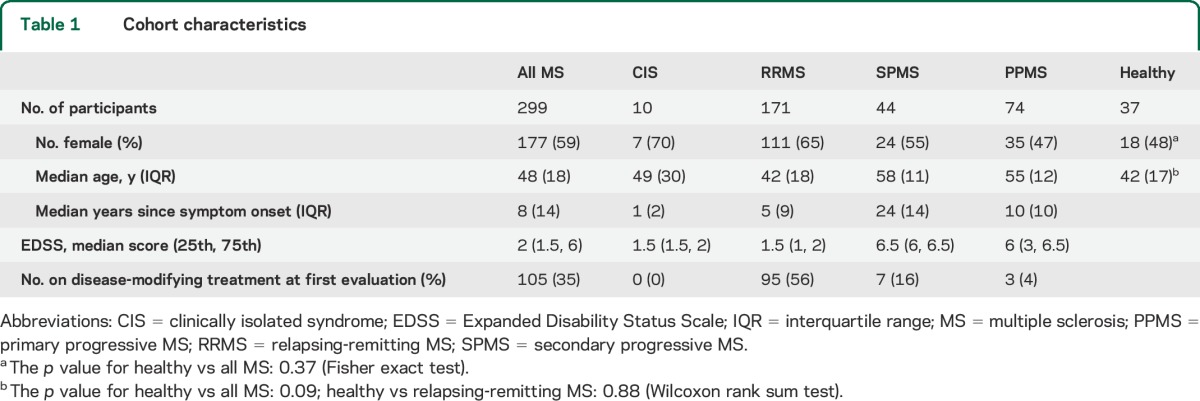

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

After the final consensus reading, the overall prevalence of leptomeningeal enhancement in the MS cohort was 74/299 (25%; figure 1, A–C, figure e-1). Leptomeningeal enhancement was found as a single focus in 48/74 cases (65%) and multiple foci in 26/74 (35%). In the latter group, 19/74 cases (27%) showed 2 foci, 5 cases 3 foci, 1 case 5 foci, and 1 case 6 foci. There was no relation between the number of foci and clinical course.

Figure 1. In vivo leptomeningeal enhancement: Radiology.

(A) Examples of leptomeningeal contrast enhancement in 4 representative MS cases. Foci of high signal (boxes) on 3T postcontrast T2-FLAIR images indicate leptomeningeal enhancement. From left to right: a 54-year-old woman with relapsing-remitting MS (EDSS score = 1.5); a 51-year-old woman with primary progressive MS (EDSS score = 6.5); a 38-year-old woman with relapsing-remitting MS (EDSS score = 1); and a 62-year-old man with primary progressive MS (EDSS score = 6.5). The findings are magnified in the corresponding boxes (arrows). In no case was enhancement present on precontrast T2-FLAIR scans (not shown). Extracerebral tissues have been masked for clarity. (B) Longitudinal assessment of leptomeningeal enhancement. High signal indicating leptomeningeal enhancement within a parietal sulcus (arrows) was stable over 4 years in a 55-year-old man with relapsing-remitting MS (EDSS score = 2.5). (C) Signal intensity on different MRI sequences. Three foci of leptomeningeal enhancement are visible on postcontrast T2-FLAIR scans (left column), but not on the corresponding precontrast T2-FLAIR (middle column). In the right column, postcontrast T1-weighted images show minimal abnormal signal that would not routinely be classified as enhancement. The first row shows images from a 42-year-old woman with relapsing-remitting MS (EDSS score = 2); second row: 30-year-old woman with relapsing-remitting MS (EDSS score = 6); and third row: 61-year-old woman with primary progressive MS (EDSS score = 6). (D) Association with meningeal vessels: high-resolution 7-tesla MRI from a 51-year-old woman with primary progressive MS (EDSS score = 6.5) shows that leptomeningeal enhancement is perivascular. T2*-weighted gradient-echo scans showing (a) the vessel (red arrow) as it appears before contrast injection; (b) bright signal around the vessel 5 minutes after contrast injection; (c) an enlarging area of bright signal 20 minutes postcontrast; and (d) partially resolving signal 40 minutes postcontrast, reflecting mixing with the slightly less bright CSF. Other vessels did not show the same finding. EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS = multiple sclerosis; T2-FLAIR = T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery.

In sum, 109 foci were found, of which 99 (91%) were supratentorial, without predilection for a particular lobe or hemisphere. Regarding shape, 53/109 (48%) were nodular, 44/109 (40%) linear, and 12/109 (11%) plate-like. Most foci (61/109, 56%) were found within a single sulcus, but 8/109 (7%) traversed several sulci. Of the remainder, 21/109 (19%) were apposed to the pial surface on the cerebral convexity, and 19/109 (17%) were within a fissure. Subtle hyperintense signal was identified on postcontrast T1-weighted images in 76/109 foci (70%); the other foci showed no enhancement relative to precontrast scans. Enhancing foci were always found in proximity to one or more vessels (figure 1D).

Of the enhancement-positive MS cases, 42/74 (57%, accounting for 62/109 enhancing foci) had at least one previous scan. The mean follow-up interval was 1.4 years, and the longest follow-up interval was 5.5 years. Of the 62 foci, 53 (85%) were stable in shape and size (figure 1B), 1 disappeared, and 2 fluctuated over time. Six new foci were appreciated in 4 cases.

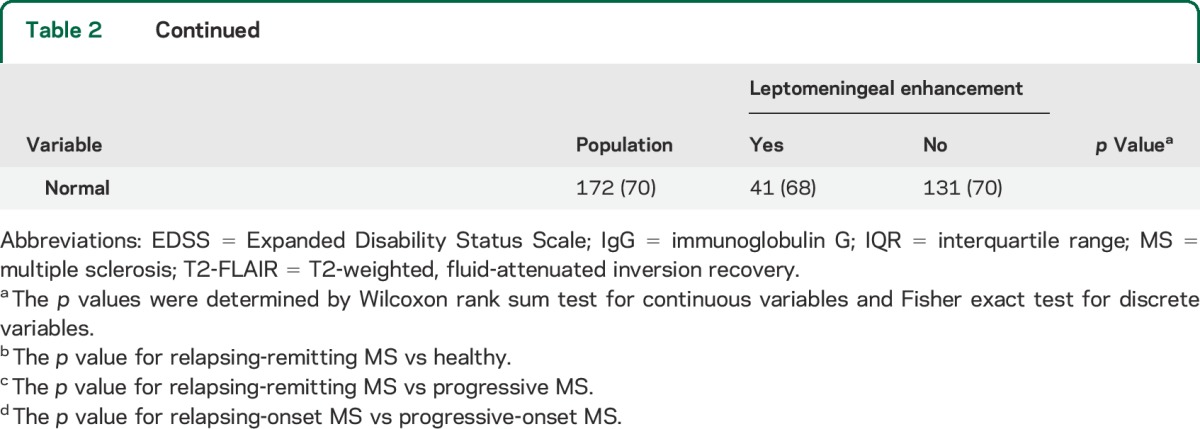

The prevalence of leptomeningeal enhancement was 1.7-fold higher (p = 0.009) in progressive MS (39/118 cases, 33%) than in relapsing-remitting MS (35/181, 19%); see table 2. Prevalence was highest in primary progressive MS (28/74 cases, 38%). There was no independent effect of sex. Median age (p = 0.0003), disease duration measured as time since first symptoms attributable to MS (p = 0.0002), and Expanded Disability Status Scale scores (p = 0.04) were higher in MS cases with leptomeningeal enhancement. Clinical phenotype (relapsing vs progressive) did not modify the effects of age or disease duration on the presence of leptomeningeal enhancement (p > 0.05 in both cases). Normalized volumes of the brain (p = 0.05) and cerebral cortex (p = 0.03) were lower in cases with leptomeningeal enhancement. There was no association between leptomeningeal enhancement and the presence or absence of contrast-enhancing white matter lesions, total white matter lesion volume, or disease-modifying treatment status (table 2).

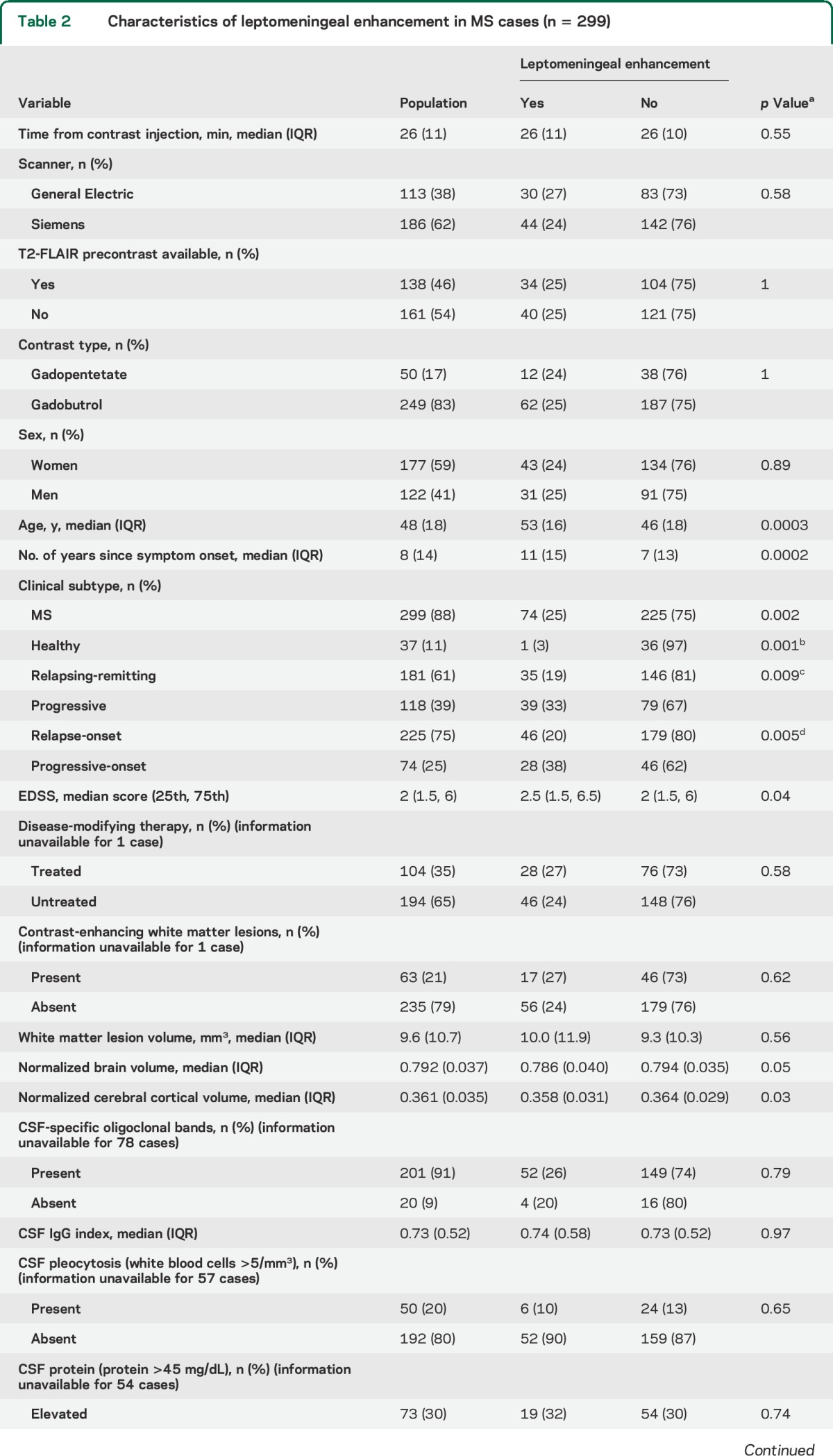

Table 2.

Characteristics of leptomeningeal enhancement in MS cases (n = 299)

In 221 of 299 MS cases (74%), results of CSF examination were available for comparison. There was no association of leptomeningeal enhancement with the CSF-specific oligoclonal bands that were present in 91% of cases, or with elevated immunoglobulin G index (CSF-to-plasma ratio), white blood cells, or protein (table 2).

One of the 37 healthy controls (2.7%) presented a single focus of leptomeningeal enhancement (p = 0.001 vs the MS cohort). In this 46-year-old healthy volunteer, a nodular focus of leptomeningeal enhancement was seen on the postcontrast T2-FLAIR scan in the right frontal region (figure e-2).

Note that there was no difference in the frequency of leptomeningeal enhancement detection between MRI scanners (p = 0.49) or between contrast agents (p = 0.71).

Neuropathologic correlation.

Three foci of nodular leptomeningeal enhancement were consistently detected in all in vivo postcontrast T2-FLAIR scans in the 2 patients with progressive MS who later came to autopsy. The gyri flanking these sulci were affected by confluent cortical demyelination, visible as high signal intensity on the postmortem 7T MRI (figures 2, e-3, e-4, and e-5) and confirmed with myelin proteolipid protein immunohistochemistry. Leptomeningeal perivascular inflammation including T cells, B cells, and macrophages was detected in the leptomeninges in the areas where in vivo enhancement had been present (figures 3, e-4, and e-5). A sulcus in the contralateral temporal lobe from the first case, which had no in vivo leptomeningeal enhancement but was identified on postmortem MRI (and later confirmed pathologically) to be associated with flanking subpial cortical lesions (figure e-3), showed no perivascular clusters of inflammatory cells.

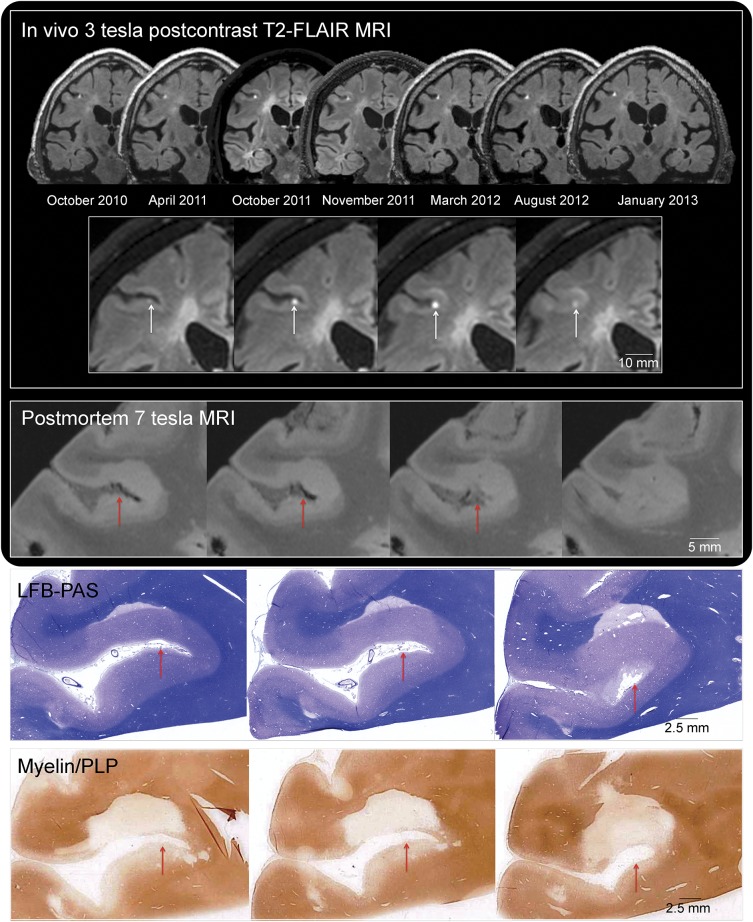

Figure 2. Leptomeningeal enhancement: Multimodal MRI-histopathology examination.

In vivo 3-tesla postcontrast T2-FLAIR MRI. The presence of stable focal leptomeningeal contrast enhancement in the right middle frontal sulcus is depicted in the 7 available postcontrast T2-FLAIR MRI scans (coronal reformations) acquired on different 3-tesla MRI scanners between 2010 and 2013. Leptomeningeal enhancement (white arrows) is located deep within the sulcus, adjacent to the cerebral cortex, and visible on 4 consecutive coronal 1-mm T2-FLAIR sections (inset, representative scans from October 2011). The expected location of in vivo leptomeningeal enhancement is indicated with red arrows in the postmortem MRI and histologic representative sections. Postmortem 7-tesla MRI: Extensive cortical and juxtacortical signal abnormality affects the brain parenchyma adjacent to the sulcus where leptomeningeal enhancement was detected in vivo (CISS sequence, 150-μm isotropic voxel resolution, representative slices). The cortical signal abnormality was not detected on in vivo MRI, although juxtacortical signal abnormality was noted. Myelin staining: In vivo and postmortem MRI-guided histopathology allowed precise localization of the target area. Serial LFB-PAS staining and myelin/proteolipid protein (PLP) immunohistochemistry were performed every 100 µm (10-μm-thick cryosections). Representative sections are well matched to both in vivo and postmortem MRI. CISS = constructive interference in steady state; LFB-PAS = Luxol fast blue/periodic acid–Schiff; PLP = proteolipid protein; T2-FLAIR = T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery.

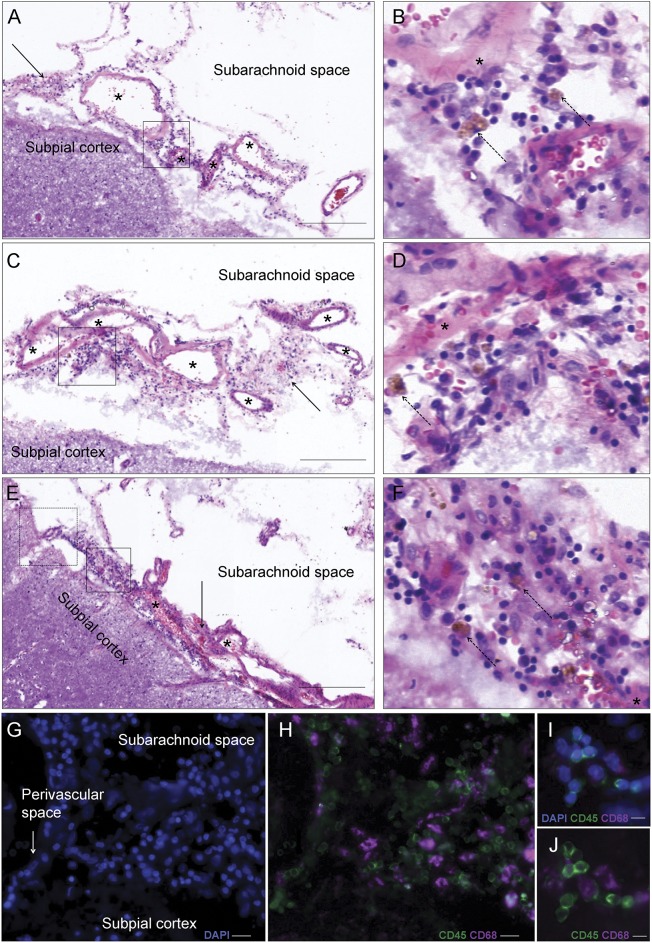

Figure 3. Histopathologic analysis of in vivo leptomeningeal enhancement.

A, C, and E show perivascular inflammatory infiltrates in the leptomeninges (arrows and boxes, with magnification of the boxes in B and D) in the area of in vivo leptomeningeal-compartment enhancement shown in figure 2 (representative 10-μm-thick hematoxylin & eosin sections; scale bars: 200 μm). B, D, and F show details of the predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate, with scattered hemosiderin-laden macrophages (brown cells, dashed arrows). Asterisks indicate meningeal blood vessels. Triple fluorescence for DAPI (nuclei, blue), CD45 (leukocyte common antigen, green), and CD68 (macrophages, purple) markers is shown in G and H (corresponding to the dashed box in E and prepared from the contiguous 10-µm sections; scale bar: 20 μm) and I and J (prepared from the adjacent 10-µm section to that in A; scale bar: 10 µm). The infiltrate consists of mostly clustered leukocytes (green; DAPI+ CD45+ CD68−) as well as scattered macrophages (purple; DAPI+ CD45+ CD68+). DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

DISCUSSION

Inflammation in the leptomeningeal compartment has received renewed attention in the MS field because of the recent pathologic description of clustered inflammatory cells in the subarachnoid space. These cells are sometimes organized into ectopic follicle-like structures containing B and T cells, and they are often found around meningeal vessels.5 The in vivo imaging and postmortem pathology reported here provide strong support for the concept that focal leptomeningeal contrast enhancement, detected in 25% of all MS cases in our cohort and up to 38% of primary progressive MS cases, is a radiologic marker for at least some foci of perivascular leptomeningeal inflammation.

Heretofore, the lack of an imaging marker for leptomeningeal inflammation has hampered a more thorough understanding of its relevance for the pathogenesis of MS. Previous autopsy studies have implicated sustained leptomeningeal inflammation in the pathophysiology of progressive MS, noting the spatial relationship of inflammatory cell clusters to demyelination of the superficial (subpial) layers of the cerebral cortex.4,6–9 Of note, these studies also suggest that such cortical lesions may continue to accumulate late in the course of the disease, even as the development of new white matter lesions becomes vanishingly rare.2 The associations among in vivo leptomeningeal enhancement, leptomeningeal inflammation, and subpial cortical demyelination in our autopsy brains, together with the substantially increased prevalence of leptomeningeal enhancement in cases of progressive MS and its long-term stability (which would be expected if such inflammation is to remain detectable at autopsy), open a new window into the investigation of progressive MS and potentially provide an opportunity for development of therapeutics to arrest it.

It is important to note that subpial cortical lesions cannot yet be reliably detected in vivo on clinical MRI scanners.22,25,26 Although global efforts are under way to address this limitation, the lack of a direct imaging marker for subpial cortical lesions renders in vivo detection of associated leptomeningeal inflammation all the more important. It is unfortunate that the same limitation precludes a definitive link between leptomeningeal enhancement and subpial cortical lesions in our MS cohort, aside from the cases that came to autopsy (where such a link was identified). Of note, however, our study also identified that the presence of leptomeningeal enhancement is associated with overall cortical volume loss (based on in vivo data), and that subpial cortical demyelination can occur in the absence of concurrent leptomeningeal inflammation and corresponding in vivo enhancement (based on ex vivo data). One interpretation of these results is that inflammation may be transiently present at the time these lesions develop, resolving in some cases later on. Another possibility is that leptomeningeal enhancement may preferentially associate with chronically inflamed cortical lesions, as demonstrated in our second autopsy case (figure e-5). Of course, etiologies beyond leptomeningeal inflammation may also have a role in cortical lesion development.

As is the case for white matter MS lesions, the association between contrast enhancement and inflammation is consistent with the perivascular topography of the inflammatory process, as contrast material reaches tissue via the vasculature. We found that leptomeningeal enhancing foci are generally perivascular, as illustrated through high-resolution 7T images (figure 1D) and pathology (figures 2, 3, e-4, and e-5). The increased sensitivity of T2-FLAIR (relative to T1-weighted imaging) to enhancement in the leptomeningeal compartment relates to its nonlinear sensitivity to small changes in the T1 relaxation time against the background of suppressed CSF.12–16 Nonetheless, for enhancement to be apparent, contrast material must collect locally in sufficient concentration. The focal nature of the enhancement and its substantially better visibility on T2-FLAIR are consistent with the notion that enhancement results from abnormal vascular permeability and subsequent local trapping of contrast material within the subarachnoid space, perhaps due to inflammation-associated leptomeningeal reactions such as fibrosis. (By corollary, it is likely that other areas of leptomeningeal inflammation, even those associated with abnormal vascular permeability, would be invisible even on postcontrast T2-FLAIR scans because of rapid mixing of contrast material with the much larger volumes of low-signal CSF.) Note that collagen deposition and upregulation of reactive fibroblasts, in the presence of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines released by inflammatory cells, have been shown to facilitate the compartmentalization of inflammatory cells and formation of tertiary lymphoid-like structures.27

Despite the relative preponderance of leptomeningeal enhancement in progressive (33% overall and 38% in the primary progressive subgroup) relative to relapsing-remitting MS (19%), it is clear that this is not exclusively a late phenomenon. Indeed, the presence of leptomeningeal inflammation in early MS has been demonstrated in biopsy studies.4 Even in relapsing-remitting MS, however, our data indicate that leptomeningeal enhancement is dissociated from the formation of new white matter lesions, which typically enhance for up to several months before resolving into a residual focus of nonenhancing signal abnormality on MRI. Instead, leptomeningeal enhancement, once present, almost invariably remains stable over time and fixed in space. This dissociation is consistent with the lack of relationship, in our cross-sectional sample, between leptomeningeal enhancement and conventional disease-modifying therapies, all of which are successful in reducing the incidence of new white matter lesions. Future prospective studies will be required to examine effects of specific therapies, including corticosteroids, on the prevalence and incidence of leptomeningeal enhancement. Indeed, in a single relapsing-remitting MS case (a 33-year-old woman with active development of white matter lesions), we observed transient resolution of focal leptomeningeal enhancement following IV infusion of 1 g of methylprednisolone for 5 days (figure e-6). Finally, a correlation between leptomeningeal enhancement and intrathecal inflammation, as detected by CSF analysis, was not found here; this is not surprising because nearly all MS cases (more than 90% in our cohort) have evidence of CSF inflammation.

This study focused on MS, so we cannot comment directly on the prevalence of leptomeningeal enhancement on T2-FLAIR in other inflammatory CNS disorders. However, we do not expect that this finding will be diagnostically specific for MS. At the same time, our data indicate that focal leptomeningeal enhancement, as seen on 3D T2-FLAIR scans performed at least 10 minutes after gadolinium injection, should not exclude the diagnosis of MS, as some prior reports have advised.28–30

In summary, leptomeningeal enhancement on postcontrast T2-FLAIR is a robust and reproducible radiologic finding in MS, and given the corresponding findings in our autopsy cases and in the wider neuropathology literature, it is highly likely to be disease-related. Further work should aim to improve sensitivity for detecting more subtle foci of leptomeningeal contrast enhancement, to describe in more detail the natural history of that enhancement, and to assess in prospective studies the extent to which it is affected by specific treatments. Indeed, as meningeal follicles contain B cells, their response to anti-CD20 therapy, which is undergoing extensive testing in MS,31–35 would be of particular interest.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Helen Griffith, Brandon Loughridge, Rosalind Hayden, Freddy Reyes, Anne Mayfield, and the staff of the NIH Neurology Clinic for expertly participating in and organizing the care of the study participants. Steven Jacobson, Raya Massoud, Philip De Jager, Zongqi Xia, Anshika Bakshi, Sonya Steele, Emily Owen, Alina von Korff, and Lori Chibnik helped to recruit the neurologically healthy cohort. Colin Shea and John Ostuni assisted with data analysis and organization, and the staff of the NIH Functional MRI Facility was instrumental in acquisition of imaging data. Abhik Ray Chaudhary, Julia Kofler, Anupara Kumar, and Thomas Talbot assisted in acquiring and processing the pathologic material. Bruce Trapp generously shared myelin proteolipid protein antibody for immunohistochemical analysis. Henry McFarland and Walter Koroshetz offered critical readings of the manuscript.

GLOSSARY

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- T2-FLAIR

T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

Footnotes

Editorial, page 12

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Daniel S. Reich, Martina Absinta, and Luisa Vuolo contributed to study concept and design. Daniel S. Reich, Martina Absinta, Luisa Vuolo, Govind Nair, Pascal Sati, Irene C.M. Cortese, Joan Ohayon, and Kaylan Fenton contributed to acquisition of data. Daniel S. Reich, Martina Absinta, Luisa Vuolo, Anuradha Rao, Govind Nair, Pascal Sati, María I. Reyes-Mantilla, Dragan Maric, Carlos A. Pardo, and Daniel S. Reich contributed to analysis and interpretation. Daniel S. Reich, Martina Absinta, Luisa Vuolo, Govind Nair, Pascal Sati, Dragan Maric, Irene C.M. Cortese, John A. Butman, Peter A. Calabresi, and Carlos A. Pardo contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Daniel S. Reich supervised the study.

STUDY FUNDING

The Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported this study.

DISCLOSURE

M. Absinta, L. Vuolo, A. Rao, G. Nair, P. Sati, I. Cortese, J. Ohayon, K. Fenton, M. Reyes-Mantilla, and D. Maric report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. P. Calabresi received personal compensation for activities with Vaccinex, Vertex, Abbott, and Prothena as a consultant. He received research support from Biogen Idec, Vertex, MedImmune, Novartis, and Abbott. J. Butman, C. Pardo, and D. Reich report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rocca MA, Messina R, Filippi M. Multiple sclerosis imaging: recent advances. J Neurol 2013;260:929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutzelnigg A, Lassmann H. Pathology of multiple sclerosis and related inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;122:15–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petzold A. Intrathecal oligoclonal IgG synthesis in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2013;262:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2188–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Magliozzi R, Stigliano E, Aloisi F. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol 2004;14:164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magliozzi R, Howell O, Vora A, et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 2007;130:1089–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Reeves C, et al. A gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010;68:477–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell OW, Reeves CA, Nicholas R, et al. Meningeal inflammation is widespread and linked to cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2011;134:2755–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SR, Howell OW, Carassiti D, et al. Meningeal inflammation plays a role in the pathology of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain 2012;135:2925–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz D, Taubenberger JK, Cannella B, McFarlin DE, Raine CS, McFarland HF. Correlation between magnetic resonance imaging findings and lesion development in chronic, active multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 1993;34:661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sormani MP, Bruzzi P. MRI lesions as a surrogate for relapses in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mamourian AC, Hoopes PJ, Lewis LD. Visualization of intravenously administered contrast material in the CSF on fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery MR images: an in vitro and animal-model investigation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:105–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths PD, Coley SC, Romanowski CA, Hodgson T, Wilkinson ID. Contrast-enhanced fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging for leptomeningeal disease in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:719–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parmar H, Sitoh YY, Anand P, Chua V, Hui F. Contrast-enhanced FLAIR imaging in the evaluation of infectious leptomeningeal diseases. Eur J Radiol 2006;58:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuoka H, Hirai T, Okuda T, et al. Comparison of the added value of contrast-enhanced 3D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition of gradient echo sequences in relation to conventional postcontrast T1-weighted images for the evaluation of leptomeningeal diseases at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:868–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews VP, Caldemeyer KS, Lowe MJ, Greenspan SL, Weber DM, Ulmer JL. Brain: gadolinium-enhanced fast fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery MR imaging. Radiology 1999;211:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N Engl J Med 2006;355:581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sibley CH, Plass N, Snow J, et al. Sustained response and prevention of damage progression in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease treated with anakinra: a cohort study to determine three- and five-year outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2375–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagnato F. Uncovering and characterizing multiple sclerosis lesions: the aid of fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images in the presence of gadolinium contrast agent. J Neuroimaging 2009;19:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kataoka H, Taoka T, Ueno S. Early contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2009;19:246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen AS, Kinkel RP, Tinelli E, Benner T, Cohen-Adad J, Mainero C. Focal cortical lesion detection in multiple sclerosis: 3 tesla DIR versus 7 tesla FLASH-T2. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012;35:537–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiee N, Bazin PL, Ozturk A, Reich DS, Calabresi PA, Pham DL. A topology-preserving approach to the segmentation of brain images with multiple sclerosis lesions. Neuroimage 2010;49:1524–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Absinta M, Nair G, Filippi M, et al. Postmortem magnetic resonance imaging to guide the pathologic cut: individualized, 3-dimensionally printed cutting boxes for fixed brains. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2014;73:780–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daams M, Geurts JJ, Barkhof F. Cortical imaging in multiple sclerosis: recent findings and “grand challenges.” Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seewann A, Kooi EJ, Roosendaal SD, et al. Postmortem verification of MS cortical lesion detection with 3D DIR. Neurology 2012;78:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charil A, Yousry TA, Rovaris M, et al. MRI and the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: expanding the concept of “no better explanation.” Lancet Neurol 2006;5:841–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller DH, Weinshenker BG, Filippi M, et al. Differential diagnosis of suspected multiple sclerosis: a consensus approach. Mult Scler 2008;14:1157–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Mahony J, Bar-Or A, Arnold DL, et al. Masquerades of acquired demyelination in children: experiences of a national demyelinating disease program. J Child Neurol 2013;28:184–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:676–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawker K, O'Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol 2009;66:460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naismith RT, Piccio L, Lyons JA, et al. Rituximab add-on therapy for breakthrough relapsing multiple sclerosis: a 52-week phase II trial. Neurology 2010;74:1860–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kappos L, Li D, Calabresi PA, et al. Ocrelizumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2011;378:1779–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bar-Or A, Calabresi PA, Arnold D, et al. Rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 72-week, open-label, phase I trial. Ann Neurol 2008;63:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.