Abstract

AIM: To systematically evaluate the efficacy of H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors in healing erosive esophagitis (EE).

METHODS: A meta-analysis was performed. A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases to include randomized controlled head-to-head comparative trials evaluating the efficacy of H2RAs or proton pump inhibitors in healing EE. Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated under a random-effects model.

RESULTS: RRs of cumulative healing rates for each comparison at 8 wk were: high dose vs standard dose H2RAs, 1.17 (95%CI, 1.02-1.33); standard dose proton pump inhibitors vs standard dose H2RAs, 1.59 (95%CI, 1.44-1.75); standard dose other proton pump inhibitors vs standard dose omeprazole, 1.06 (95%CI, 0.98-1.06). Proton pump inhibitors produced consistently greater healing rates than H2RAs of all doses across all grades of esophagitis, including patients refractory to H2RAs. Healing rates achieved with standard dose omeprazole were similar to those with other proton pump inhibitors in all grades of esophagitis.

CONCLUSION: H2RAs are less effective for treating patients with erosive esophagitis, especially in those with severe forms of esophagitis. Standard dose proton pump inhibitors are significantly more effective than H2RAs in healing esophagitis of all grades. Proton pump inhibitors given at the recommended dose are equally effective for healing esophagitis.

Keywords: Erosive esophagitis, H2-receptor antagonists, Proton pump inhibitors, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common chronic conditions affecting 20-40% of adult populations and has a major adverse impact on the quality of life[1-3]. About 40-60% of patients with symptoms of GERD may have substantial injury of esophageal mucosa ranging from mild inflammation and erythema to various grades of erosions. The major complications of GERD are esophageal ulcer and bleeding, esophageal stricture, and Barrett’s esophagus[1-4].

Reflux esophagitis is generally considered to be the result of prolonged and repeated exposure of the distal esophageal mucosa to acidic gastric contents[5,6]. It is increasingly clear that the key to reducing symptoms and to healing erosive esophagitis is to decrease the duration of exposure to the acidic refluxate. Acid-suppressing drugs that have been used to treat GERD include H2-receptor antagonist (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors. The efficacy of medical treatment depends on the ability to increase and maintain the intragastric and intra-esophageal pH above 4.0 over the 24-h period[7,8]. H2RAs are limited in their ability to inhibit postprandial gastric acid secretion and are ineffective in controlling reflux symptoms and healing esophagitis[9,10]. In contrast to H2RA, proton pump inhibitors block the final step of acid secretion, resulting in a profound and long-lasting acid suppression regardless of the stimulus[11,12]. Results from 33 randomized clinical trials with over 3 000 patients showed that symptomatic relief could be anticipated in 83% of proton pump inhibitors-treated patients compared with 60% of patients receiving H2RAs. Similarly, esophagitis was healed in 78% and 50% of patients treated with proton pump inhibitors and H2RAs, respectively[13]. Previously there have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of clinical trials assessing the effects of medical treatments for erosive esophagitis[14-17]. Chiba and colleagues[14], and Caro and colleagues[15] compared the effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors and H2RAs in the healing of esophagitis, whereas the comparative efficacy among proton pump inhibitors was analyzed by Sharma et al[16] and Edwards et al[17]. However, comparison of the effects between treatments with proton pump inhibitors and H2RAs in patients with esophagitis has been difficult because of the difference in the study design. For example, studies included in the previous meta-analyses were not all head-to-head comparative trials[14,15]. The overall estimates of healing rate calculated by one-step pooling from different pairs of comparatives, may produce bias due to the ignorance of study differences such as sample size and differential difference in effect sizes. In addition, healing of esophagitis is significantly influenced by the initial grade of esophagitis, with healing rate being lower for the severe form of esophagitis than for the mild form of esophagitis[18-20]. However, no meta-analysis has been published to systematically evaluate the impact of the initial grading of esophagitis on esophagitis healing rates in head-to-head comparative trials. Therefore, the objectives of the current study were firstly to evaluate any difference in healing erosive esophagitis between proton pump inhibitors and H2RAs in head-to-head comparative trials, and secondly to estimate the impact of baseline grade of esophagitis on esophagitis healing rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

A computerized literature search was performed in the PubMed, Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases for clinical trials published in English up to May 2004 with the following MeSH terms and/or text words in various combinations: gastroesophageal reflux, GERD, GORD, esophagitis, and healing, as well as the name of each respective drug (H2-receptor antagonists: cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine, roxatidine; proton pump inhibitors: omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabap-razole, esomeprazole). The title and abstract of all potentially relevant studies were screened for their relevance before retrieval of full articles. Full articles were also scrutinized for relevance if the title and abstract were ambiguous. Fully recursive searches were performed from the reference list of all retrieved articles to ensure a complete and comprehensive search of the published literature. All searches were conducted independently by at least two reviewers.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Randomized, controlled clinical trials in adults with an endoscopically confirmed diagnosis of GERD. (2) Two or more treatment arms: high dose vs standard dose H2RA, or an H2RA vs a proton pump inhibitor, or a proton pump inhibitor vs a proton pump inhibitor. (3) Healing of esophagitis was documented by endoscopy. (4) Studies with explicit information about the number of patients treated in each group, drug dosage and schedule, and healing rate of esophagitis.

We excluded studies that only assessed symptom relief without endoscopic documentation of esophagitis healing. Also excluded were studies dealing only with relapsed or recurrent esophagitis, studies of pediatric patients, duplicate publications or studies published only in abstract form, or those focusing on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Combination treatments such as an anti-secretory agent and a prokinetic drug were also excluded.

Data extraction

Data was extracted from each study independently and entered into a computerized database. Differences were resolved by discussion to reach consensus between the reviewers. The information retrieved covered country of study, study design, characteristics of population, grading of esophagitis, treatment regimen, number of patients treated, evaluated and healed, and confounding variables such as alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and caffeine use, where applicable. Healing data, up to 12 wk were extracted for both intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. Data on healing based on the initial grade of esophagitis were also extracted, if applicable. In studies where only per-protocol healing rates were reported, we calculated the ITT healing rates based on the initial randomized number of patients. Articles that did not specify the type of analysis were assumed to report per-protocol data.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed by a series of validity criteria, including study design, level of blinding, method of randomization, patient selection, baseline characteristics, severity of esophagitis, definition of healing, compliance, and analysis by intention to treat criteria. Discrepancies in quality assessment were resolved by consensus among the authors. No quality score was assigned to any study to avoid possible introduction of subjectivity by the authors.

Statistical analysis

The data were grouped as follows: high dose vs standard dose H2RAs; proton pump inhibitors vs H2RAs, or one proton pump inhibitor vs another proton pump inhibitor. We defined standard dose of each drug as: ranitidine 300 mg/d, famotidine 40 mg/d, nizatidine 300 mg/d, cimetidine 800 mg/d, omeprazole 20 mg/d, lansoprazole 30 mg/d, pantoprazole 40 mg/d, rabeprazole 20 mg/d, esomeprazole 40 mg/d. The newer proton pump inhibitors include lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole.

The outcomes considered were healing rates of esophagitis for each group at different time points (2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 wk), based on initial grade of esophagitis, if applicable. Healing rate was calculated by pooling raw data from qualified studies within each group. These data were then expressed as a healing-time curve that plotted the cumulative percentage of patients healed vs the end point in weeks.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), under a random-effects model[21], were calculated using raw data of the selected studies at specified time points (2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 wk). The potential effect of publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot suggested by Egger et al[22]. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Q value calculated from the Mentel-Haenszel method. In the presence of statistical heterogeneity, we searched for the sources of any possible clinically important heterogeneity, i.e., methodological or biological heterogeneity. We did not simply exclude outliers on the basis of statistical test of heterogeneity. Furthermore, to test the robustness of the analysis, we performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate whether exclusion of a single study substantially altered the result of the summary estimate.

All analyses were carried out using EasyMa software for meta-analysis written by M Cucherat, Lyon, France (EasyMa, 2001).

RESULTS

Study characteristics

We identified a total of 485 citations with the computerized search. Screening of the title and abstract of the citations identified 72 potentially relevant studies for full article retrieval. Of these, 52 studies met the inclusion criteria[19,20,23-72], and 20 studies were subsequently excluded for the following reasons: 17 were not head-to-head comparative studies[73-89], 1 duplicate publication[90], 1 without raw data[91], and 1 with a confusing treatment allocation[92]. The manual search of the reference list of the retrieved articles did not yield any additional studies. Of the 52 studies, the majority were double blind studies (51/52, 98.1%). Ten (19.2%) compared high dose H2RA with standard dose H2RA[23-32], 26 (50.0%) compared a proton pump inhibitor with an H2RA[33-57,71], and 16 (30.8%) compared a proton pump inhibitor with another proton pump inhibitor[19,20,58-70,72]. Only 25 (48.1%) reported raw healing data by the initial grade of Esophagitis[19,20,23,24,30,32,35,38,43-47,49,52,53,55-58,60,61,69-71].

The proportion of patients with a smoking history was reported in 61.5% of studies, alcohol consumption was reported in 48.1% of studies. The initial grade of esophagitis was reported in 58% studies. However, only 48.1% studies provided raw data on healing by the initial grade of esophagitis.

Healing of esophagitis

High dose H2RAs vs standard dose H2RAs Ten studies involving 27 treatment arms compared high dose (n = 2041 patients) with standard dose H2RAs (n = 1967 patients)[23-32]. Table 1 summarizes the pooled healing rates of esophagitis in patients treated with high dose H2RAs vs standard dose H2RAs. Statistical significance was achieved at 4, 8 and 12 wk, indicating that high dose H2RAs healed significantly more esophagitis than did standard dose H2RAs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Healing rate of esophagitis by ITT with standard dose vs high dose of H2RA at 3, 4, 6, 8, 12 wk

| 3-wk | 4-wk | 6-wk | 8-wk | 12-wk | ||

| Number of comparisons | 1 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 12 | |

| High dose | Pooled data | 29/169 | 297/669 | 607/1 294 | 413/669 | 1 142/1 729 |

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 17.2 | 44.4 | 46.9 | 61.7 | 66.0 | |

| Standard dose | Pooled data | 33/168 | 198/573 | 584/1 361 | 309/573 | 920/1 520 |

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 19.6 | 34.6 | 42.9 | 53.9 | 60.5 | |

| Summary RR | 0.874 | 1.281 | 1.096 | 1.165 | 1.084 | |

| 95% CI | 0.557-1.371 | 1.036-1.583 | 0.930-1.293 | 1.020-1.329 | 1.019-1.152 |

ITT, intention-to-treat analysis; No, number; RR, relative risk; 95%CI.

No comparative study reported data on the healing of esophagitis at 2 wk. Only one study[29] reported healing rates at 3 wk, of 17.2% (29/169) for high dose H2RAs and 19.6% (33/168) for standard dose H2RAs (RR 0.87, 95%CI 0.56-1.37) (Table 1).

Proton pump inhibitors vs H2RAs There were 14 studies with 28 treatment arms comparing standard dose proton pump inhibitors (n = 861 patients) with standard dose H2RAs (n = 752 patients)[33-45,71]. The pooled healing rates achieved with the standard dose proton pump inhibitors were superior to that of H2RAs at all given time points (Table 2). Similar findings were observed when the comparison was made between high dose H2RAs (n = 234 patients) and the standard dose proton pump inhibitors (n = 237 patients)[50,51] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Healing rate of esophagitis by ITT at 2, 3, 4, 8, 12 wk comparing proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) with H2RA

|

PPIs |

H2RA |

|||||||

| 2-wk | 4-wk | 8-wk | 12-wk | 2-wk | 4-wk | 8-wk | 12-wk | |

| sd PPIs vs sd H2RA | ||||||||

| Number of arms | 2 | 13 | 12 | 2 | 13 | 12 | ||

| Pooled data | 116/183 | 577/824 | 640/783 | 60/163 | 271/713 | 350/673 | ||

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 63.4 | 70.0 | 81.7 | 36.8 | 38.0 | 52.0 | ||

| Summary RR | 1.759 | 1.832 | 1.586 | |||||

| 95%CI | 1.398-2.213 | 1.622-2.070 | 1.438-1.749 | |||||

| hd PPIs vs sd H2RA | ||||||||

| Number of arms | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Pooled data | 150/204 | 175/201 | 72/80 | 79/211 | 106/207 | 49/81 | ||

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 73.5 | 87.1 | 90.0 | 37.4 | 51.2 | 60.5 | ||

| Summary RR | 1.722 | 1.623 | 1.488 | |||||

| 95%CI | 1.464-2.027 | 1.417-1.859 | 1.230-1.800 | |||||

| sd PPIs vs hd H2RA | ||||||||

| Number of arms | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Pooled data | 152/235 | 208/235 | 87/234 | 155/234 | ||||

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 64.7 | 88.5 | 37.2 | 66.2 | ||||

| Summary RR | 1.744 | 1.336 | ||||||

| 95%CI | 1.442-2.110 | 1.206-1.481 | ||||||

| ld PPIs vs sd H2RA | ||||||||

| Number of arms | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Pooled data | 187/279 | 219/279 | 120/276 | 161/276 | ||||

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 67.0 | 78.5 | 43.5 | 58.3 | ||||

| Summary RR | 1.605 | 1.374 | ||||||

| 95%CI | 1.156-2.229 | 1.081-1.744 | ||||||

hd: high dose; sd: standard dose; ld: low dose; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis; No., number; RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% CIs.

Three studies compared low dose proton pump inhibitors (n = 279 patients) with standard dose H2RAs (n = 276 patients) for healing esophagitis[52,53,71]. The pooled healing rates of the low dose proton pump inhibitors were higher than that of the standard dose H2RAs at both 4 and 8 wk (Table 2).

Omeprazole 20 mg daily vs other proton pump inhibitors Eleven studies with 23 treatment arms reported comparative results on the healing of esophagitis between omeprazole 20 mg daily (n = 3137 patients) and other proton pump inhibitors at standard doses (n = 3397 patients)[20,59-68]. No significant difference in the healing rate was observed between omeprazole 20 mg daily and other proton pump inhibitors at 2-8 wk (Table 3).

Table 3.

Healing rate (ITT) of esophagitis at 2, 4, 8 wk comparing PPIs with omeprazole

|

Other PPIs |

Omeprazole |

|||||

| 2-wk | 4-wk | 8-wk | 2-wk | 4-wk | 8-wk | |

| sd PPIs vs sd Omeprazole | ||||||

| Number of arms | 1 | 12 | 12 | 1 | 12 | 12 |

| Pooled data | 264/421 | 2 615/3 412 | 3 050/3 411 | 257/431 | 2 229/3 217 | 2 719/3 216 |

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 62.7 | 76.6 | 89.4 | 59.6 | 69.3 | 84.5 |

| Summary RR | 1.052 | 1.044 | 1.061 | |||

| 95%CI | 0.945–1.171 | 0.983-1.109 | 0.979-1.055 | |||

| ld PPIs vs sd Omeprazole | ||||||

| Number of arms | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Pooled data | 590/822 | 724/822 | 551/811 | 707/811 | ||

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 71.8 | 88.1 | 67.9 | 87.2 | ||

| Summary RR | 1.026 0.981 | |||||

| 95%CI | 0.904-1.164 | 0.870-1.105 | ||||

| sd PPIs vs hd Omeprazole | ||||||

| Number of arms | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Pooled data | 310/440 | 284/337 | 302/434 | 282/332 | ||

| Pooled healing rate (%) | 70.5 | 84.3 | 69.6 | 84.9 | ||

| Summary RR | 1.031 | 0.985 | ||||

| 95%CI | 0.937-1.015 | 0.883-1.099 | ||||

hd: high dose; sd: standard dose; ld: low dose; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis; No., number; RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% CIs.

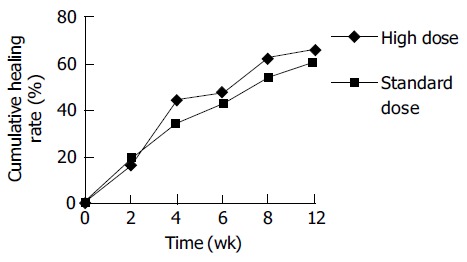

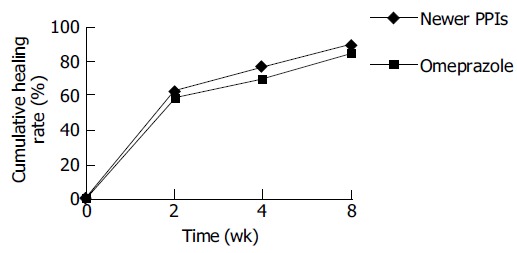

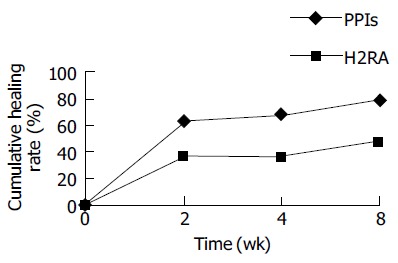

The esophagitis healing time curves are depicted in Figures 1-3. As shown in Figure 1, high dose H2RA achieved higher healing rates than standard dose H2RA. However, the healing rate achieved with standard dose proton pump inhibitors at 2 wk was even higher than that of H2RAs at wk 8 (63.4% vs 52.0%), suggesting that proton pump inhibitors healed esophagitis significantly faster than did H2RAs (Figure 2). Similar healing rates were also observed when the newer proton pump inhibitors were compared with omeprazole 20 mg daily (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Healing-time curve of esophagitis in patients treated with H2RA. Statistical significance was achieved at 4, 8, and 12 wk, indicating that high dose H2RAs achieved significantly better healing rates for erosive esophagitis than standard dose H2RAs.

Figure 3.

Healing-time curve of esophagitis in patients treated with standard dose of the newer proton pump inhibitors vs omeprazole. No significant difference in the pooled healing rates between the newer proton pump inhibitors and omeprazole was observed.

Figure 2.

Healing-time curve of esophagitis in patients treated with standard doses of proton pump inhibitors vs H2RAs. At wk 2, 4, 8, proton pump inhibitors significantly healed more patients than did H2RAs.

Refractory esophagitis

Refractory esophagitis was defined as treatment failure with a standard dose of H2RAs given for at least 12 wk[55-57]. Three studies compared the effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors with ranitidine for the treatment of refractory esophagitis[55-57] (Table 4). Two of them reported that lansoprazole 30 mg daily achieved significantly higher healing rates than ranitidine 300 mg, daily at 4 wk (RR 1.38; 95%CI 1.31-1.83) and 8 wk (RR 2.54; 95%CI 1.86-3.46)[55,56]. The other study indicated that treatment with high dose omeprazole (40 mg/d) in patients refractory to H2RAs therapy significantly improved esophagitis healing when compared to high dose ranitidine (600 mg/d) (RR 3.69, 95%CI 2.30-5.90 at 4 wk; and RR2.03, 95%CI 1.54-2.67 at 8 wk)[57].

Table 4.

Healing rate of refractory esophagitis at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 wk comparing PPIs with H2RA

| Author |

PPIs |

H2RAs |

||||||||||

|

Number of |

Healing rate ( ITT ) |

Number of |

Healing rate ( ITT ) |

|||||||||

| Drug | Dose | Patient | 4 wk | 8 wk | 12 wk | Drug | Dose | Patient | 4 wk | 8 wk | 12 wk | |

| sd PPIs vs sd H2RA | ||||||||||||

| Feldman (55) | Lan | 30 o.d. | 61 | 54/61 | Ran | 150 b.d. | 32 | 12/32 | ||||

| Sontag (56) | Lan | 30 o.d. | 105 | 75/105 | 84/105 | Ran | 150 b.d. | 54 | 28/54 | 16/541 | ||

| Pooled data | 166 | 75/105 | 138/166 | 86 | 28/54 | 28/86 | ||||||

| Pooled rate (%) | 71.4 | 83.1 | 51.9 | 32.6 | ||||||||

| hd PPIs vs hd H2RA | ||||||||||||

| Lundell (57) | Ome | 40 o.d. | 51 | 32/51 | 35/51 | 46/51 | Ran | 300 b.d. | 47 | 8/47 | 18/47 | 22/47 |

Ome: omeprazole; Lan: lansoprazole; Ran: ranitidine; o.d.: once daily in the morning; b.d.: twice daily; h.d.: high dose; sd: standard dose. This study did not report cumulative healing rate at 8 wk. All patients’ endpoint was at 8 wk. The decreased healing rate at 8 wk for ranitidine group may be due to subsequent relapse of esophagitis.

Healing by initial grade of esophagitis

Twenty-five studies[19,20,23,24,30,32,35,38,43-47,49,52,53,55-58,60,61,69-71] with 54 treatment arms provided raw data on healing by the initial grade of esophagitis (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7). Because data by intention-to-treat analysis were not available from the majority of trials, the healing rate by per-protocol analysis was therefore used.

Table 5.

Healing by grade with standard dose vs high dose of H2RA at 4, 6, 8, 12 wk (PP rate)

|

4-wk |

6-wk |

8-wk |

12-wk |

||||||||

| II | III | I | II | III | II | III | I | II | III | ||

| Number of arms | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | |

| Standard dose | Pooled data | 84/190 | 22/105 | 86/137 | 102/266 | 42/180 | 126/187 | 37/105 | 107/129 | 264/383 | 119/256 |

| Pooled rate (%) | 44.2 | 21.0 | 62.8 | 38.3 | 23.3 | 67.4 | 35.2 | 82.9 | 69.0 | 46.5 | |

| High dose | Pooled data | 177/325 | 60/198 | 112/157 | 120/272 | 60/214 | 226/323 | 92/198 | 122/153 | 400/532 | 190/376 |

| Pooled rate (%) | 54.4 | 30.3 | 71.3 | 44.1 | 28.0 | 70.0 | 46.5 | 79.7 | 75.2 | 50.5 | |

| Summary RR | |||||||||||

| 95% CI | 1.231 | 1.430 | 1.136 | 1.150 | 1.200 | 1.039 | 1.316 | 0.962 | 1.032 | 1.059 | |

| 1.020-1.486 | 0.941-2.202 | 0.966-1.337 | 0.939-1.408 | 0.854-1.686 | 0.919-1.174 | 0.977-1.774 | 0.860-1.076 | 0.961-1.108 | 0.913-1.229 | ||

PP, per-protocol analysis; No., number; RR, relative risk; 95%CI.

Table 6.

Healing by grade at 4, 8, 12 wk comparing PPIs with H2RAs (PP rate)

|

4 wk |

8 wk |

12 wk |

|||||||||

| I | II | III | IV | I | II | III | IV | I | II | ||

| Number of arms | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| sd PPIs | Pooled data | 53/60 | 128/162 | 20/54 | 23/23 | 166/178 | 28/47 | 2/3 | |||

| Pooled rate (%) | 88.3 | 79.0 | 37.0 | 100.0 | 93.3 | 59.6 | 66.7 | ||||

| sd H2RAs | Pooled data | 27/54 | 65/172 | 2/41 | 16/25 | 101/182 | 6/34 | 0/2 | |||

| Pooled rate (%) | 50.0 | 37.8 | 4.9 | 64.0 | 55.5 | 17.6 | 0 | ||||

| Summary RR | 1.760 | 2.037 | 5.588 | 1.502 | 1.648 | 2.766 | 2.525 | ||||

| 95%CI | 1.329-2.332 | 1.631-2.545 | 1.701-18.363 | 1.107-2.038 | 1.440-1.885 | 1.284-5.916 | 1.046-6.093 | ||||

| No. of arms | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| hd PPIs | Pooled data | 40/46 | 88/123 | 21/30 | 46/46 | 104/120 | 24/30 | 29/29 | 42/46 | ||

| Pooled rate (%) | 87.0 | 71.5 | 70.0 | 100.0 | 86.7 | 80.0 | 100.0 | 91.3 | |||

| sd H2RAs | Pooled data | 26/50 | 49/126 | 3/28 | 37/49 | 62/121 | 6/28 | 28/32 | 19/35 | ||

| Pooled rate (%) | 52.0 | 38.9 | 10.7 | 75.5 | 51.2 | 21.4 | 87.5 | 54.3 | |||

| Summary RR | 1.665 | 1.835 | 6.110 | 1.300 | 1.689 | 3.626 | 1.111 | 1.676 | |||

| 95%CI | 1.248-2.222 | 1.436-2.345 | 2.138-17.459 | 1.102-1.534 | 1.400-2.036 | 1.772-7.418 | 0.957-1.291 | 1.222-2.298 | |||

| Number of arms | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| ld PPIs | Pooled data | 144/175 | 34/42 | 9/28 | 162/175 | 42/44 | 15/28 | ||||

| Pooled rate (%) | 82.3 | 81.0 | 32.1 | 92.6 | 95.5 | 53.6 | |||||

| sd H2RAs | Pooled data | 104/175 | 15/50 | 1/22 | 132/175 | 27/49 | 2/21 | ||||

| Pooled rate (%) | 59.4 | 30.0 | 4.5 | 75.4 | 55.1 | 9.5 | |||||

| Summary RR | 1.384 | 2.698 | 7.071 | 1.227 | 1.732 | 5.625 | |||||

| 95%CI | 1.202-1.592 | 1.724-4.224 | 0.967-51.707 | 1.116-1.349 | 1.335-2.249 | 1.440-21.980 | |||||

| Refractory esophagitis | |||||||||||

| Number of arms | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| sd PPIs | Pooled data | 62/77 | 11/22 | 105/116 | 13/15 | 18/29 | |||||

| Pooled rate (%) | 80.5 | 50.0 | 90.5 | 86.7 | 62.1 | ||||||

| sd H2RAs | Pooled data | 20/40 | 1/11 | 26/61 | 2/8 | 0/14 | |||||

| Pooled rate (%) | 50.0 | 9.1 | 42.6 | 25.0 | 0 | ||||||

| Summary RR | 1.606 | 5.500 | 2.117 | 3.229 | 35.881 | ||||||

| 95%CI | 1.158-2.228 | 0.835-25.337 | 1.575-2.845 | 1.034-10.091 | 0.728-1767.6 | ||||||

sd: standard dose; ld: low dose.

Table 7.

Healing by grade at 4, 8 wk comparing standard dose of other PPIs vs omeprazole

|

4-wk |

8-wk |

||||||||

| I | II | III | IV | I | II | III | IV | ||

| Number of arms | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| sd PPIs | Pooled data | 195/239 | 302/362 | 148/210 | 3/7 | 214/235 | 329/360 | 175/209 | 2/4 |

| Pooled rate (%) | 81.6 | 83.4 | 70.5 | 42.9 | 91.1 | 91.4 | 83.7 | 50.0 | |

| sd omeprazole | Pooled data | 190/238 | 315/393 | 132/195 | 3/5 | 214/233 | 345/390 | 159/188 | 1/2 |

| Pooled rate (%) | 79.8 | 80.2 | 67.8 | 60.0 | 91.8 | 88.5 | 84.6 | 50.0 | |

| Summary RR | 1.022 | 1.041 | 1.041 | 0.733 | 0.992 | 1.033 | 0.990 | 1.000 | |

| 95%CI | 0.936-1.116 | 0.973-1.113 | 0.914-1.186 | 0.250-2.147 | 0.938-1.048 | 0.985-1.084 | 0.927-1.057 | 0.213-4.694 | |

sd: standard dose.

When the healing rate was adjusted according to the initial severity of esophagitis, no significant differences in the healing rates was observed when patients with the severe form of esophagitis (≥ grade III) were treated with either high dose or standard dose H2RAs. However, a significant difference was observed for patients with grade II esophagitis at 4 wk (Table 5). No patients with grade IV esophagitis were included in any of the studies comparing high dose with standard dose H2RAs.

Proton pump inhibitors achieved consistently and significantly higher healing rates than H2RAs across all grades of esophagitis, irrespective of the dose and duration of treatment (Table 6). With a wide range of CI, the superiority of proton pump inhibitors over H2RAs was even greater when the initial grade of esophagitis was considered in studies of patients with refractory esophagitis (Table 6) despite that one study reported the same effects on grade I esophagitis at 12 wk, when omeprazole 40 mg daily was compared with ranitidine 300 mg daily[47]. The healing rates were similar between omeprazole and the newer proton pump inhibitors across all grades of esophagitis (Table 7).

Testing for between-study heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses

In the comparison of the healing rates achieved with omeprazole and the newer proton pump inhibitors, a significant heterogeneity was found at 4 and 8 wk (P < 0.001). However, no further heterogeneity (P = 0.43 at 4 wk, and P = 0.92 at 8 wk) was found after exclusion of the studies from Kahrilas et al[67] and Richter et al[68] suggesting that the heterogeneity was caused by these two studies. Further scrutiny of these two studies revealed that Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) positive patients were excluded in both studies, whereas other studies did not use H pylori status as an exclusion criterion. No additional confounding factors such as the study design, level of blinding and compliance of patients were identified. Sensitivity analysis showed no difference in the healing rates of erosive esophagitis between omeprazole and the newer proton pump inhibitors (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.96-1.04 at 4 wk; and RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.97-1.02) when the data from the two studies were excluded. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in any other comparisons.

Publication bias

Tests for publication bias were assessed with funnel plots using RRs against the sample size of each study. Due to the inadequacy of the number of studies in each comparison, funnel plots did not demonstrate strong patterns. Therefore, figures are not shown.

DISCUSSION

There have been a few systematic reviews and meta-analyses summarizing the effect of medical treatments for reflux esophagitis[14-17]. However, most of them suffered from methodological flaws. The current study was the first attempt to systematically evaluate the effects of antisecretory agents in healing esophagitis based on head-to-head comparative trials. We believe that analysis of comparative trials provides more robust results than that obtained from simple pooling of results from non-comparative trials because no stratification was used in the latter form of analysis. We found that high dose H2RAs was superior to standard dose H2RAs in healing erosive esophagitis at wk 4, 8, and 12, and proton pump inhibitors achieved significantly higher healing rates of esophagitis than did H2RAs, irrespective of dose and treatment duration. However, no statistically significant difference in healing rates was observed between standard dose omeparzole and the newer proton pump inhibitors after 4 and 8 wk of treatment.

The difference in the rate of healing esophagitis between proton pump inhibitors and H2RAs can also be expressed as a healing-time curve for the ease of comparison[14]. Using this method, we have shown that proton pump inhibitors healed esophagitis at a rate approximately twice that of H2RAs at all time points and the healing rate achieved at 2 wk with proton pump inhibitors was greater than that obtained with H2RAs at 8 wk. This is consistent with the findings from previous meta-analyses using a different study design[14-17].

H2RAs are less effective for healing esophagitis because they cannot effectively inhibit meal-stimulated acid secretion[9,10]. Moreover, tolerance may occur to H2RAs, resulting in a significant decrease in their anti-secretory effect[93,94]. Therefore, patients with reflux esophagitis often require high dose H2RAs to maintain an intragastric pH above the critical threshold of 4.0 to achieve satisfactory symptom relief and remission of esophagitis[7,8]. Proton pump inhibitors have been proved to be effective in suppressing gastric acid secretion throughout the 24-h period, including meal-stimulated acid production[95,96]. So far, tolerance to proton pump inhibitors has not been reported in the literature even after long-term treatment.

The severity of esophagitis is a good predictor of a successful treatment[97]. In this analysis, we have shown that high dose H2RAs achieved a significantly better healing rate of esophagitis than standard dose H2RAs. However, this difference disappeared when the results were adjusted by the initial grade of esophagitis except for the comparison at 4 wk when high dose H2RAs healed 10% more esophagitis (Table 5). A possible explanation for the rapid loss of superiority of anti-secretory effect of high dose H2RAs over standard dose H2RAs after 4 wk could be due to the subsequent development of tolerance to the continuous use of H2RAs[93,94].

Our study has confirmed that proton pump inhibitors were significantly more effective than H2RAs in healing erosive esophagitis across all grades. In patients with mild forms of esophagitis (grades I and II), the healing rate achieved with proton pump inhibitors was significantly higher than that with H2RAs (100.0% vs 64.0% for grade I, and 93.3% vs 55.5% for grade II) at 8 wk (Table 6). This suggested that, even in patients with the mild form of esophagitis, H2RAs is a less effective treatment compared to proton pump inhibitors. The difference was even greater in patients with grade III/IV esophagitis. The healing rate achieved with proton pump inhibitors at 8 wk was 59.6%, but only 17.6% with H2RAs (Table 6). In patients refractory to H2RAs, proton pump inhibitors healed 50.0% and 62.1% of grade IV esophagitis after 4 and 8 wk of treatment, respectively (Table 4). Thus, proton pump inhibitors are significantly more effective than H2RAs for treating all grades of esophagitis, including patients refractory to H2RAs.

It is known that individual proton pump inhibitors differ with respect to the onset of action and duration of effect because of the variability in their bioavailability. Although omeprazole has a relative lower bioavailability than other proton pump inhibitors[98-100], which may contribute to the late onset of symptom relief, this has not been translated into a disadvantage in healing rate of esophagitis of all grades when compared with the newer proton pump inhibitors according to the results of this analysis.

A statistically significant heterogeneity was found in the overall analysis comparing the efficacy of healing esophagitis among different proton pump inhibitors. Two studies identified to have contributed to the heterogeneity, compared esomeprazole to omeprazole and excluded patients with H pylori infection in their analyses[67,68]. Although a higher healing rate of reflux esophagitis has been observed in patients with H pylori infection compared to uninfected patients when treated with proton pump inhibitors[101,102], there is no evidence that esomeprazole would work better on H pylori negative patients. Therefore, there might in fact be real difference in efficacy between esomeprazole and omeprazole, because esomeprazole is the enantionmer of omeprazole and the active compound is the achiral cyclic sulfenamide. Comparing 40 mg of esomeprazole with 20 mg of omeprazole would be more or less the same, as comparing double dose of omeprazole[103]. More data are needed to further confirm the presumption.

There are several limitations in this meta-analysis. Firstly, the quality of a meta-analysis , in general is dependent on the quality of original studies, particularly the study design and reporting. To correct reporting bias from original studies is difficult and requires collaboration of investigators involved. Because of the practical difficulties, such as lapse in time between the time of publication and the time of this analysis, we did not contact investigators for raw data or clarification of unclear presentation. Secondly, three different esophagitis grading systems were used in the individual studies, which might have confounded the results of analyses. Huang et al[104] previously reported that there is a systematic difference in healing rates between studies using Hetzel-Dent scoring system and those using Savary-Miller system. Therefore, we considered that the impact of different esophagitis scoring systems on the analysis of esophagitis healing rates deserves a systematic evaluation in its own right. This warrants an immediate consensus of using a standard esophagitis scoring system among investigators so that a truly meaningful comparison of the efficacy of different drugs can be made. Thirdly, the stratified analysis by the initial grade of esophagitis may also be biased because per-protocol data were used in the analysis. Fourthly, we excluded meeting abstracts and non-English publications for technical reasons such as inadequate reporting of outcomes in meeting abstracts and no resources for translation of non-English articles. This might have introduced selection bias. To estimate the magnitude of possible impact, we searched the literature and identified six articles published in non-English literature, but with an English abstract[18,105-109]. Four studies compared a standard dose proton pump inhibitor with an H2RA, one between two H2RAs and one between two different doses of cimetidine. The conclusions of these trials are consistent with those of this meta-analysis. Therefore, we believe that the inclusion of non-English studies would not change the conclusions of this analysis. Fifthly, relief of reflux symptoms is another important aspect in the management of patients with GERD. However, the large variability in measuring and reporting symptom data in the literature prohibited us from conducting a reliable meta-analysis of the effects of antisecretory agents on relieving reflux symptoms. This requires an urgent attention to establishing a standard instrument for the assessment of symptom response in patients with GERD.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis of comparative trials clearly identifies that H2RAs are not effective treatment for patients with esophagitis of all grades irrespective of dose. Proton pump inhibitors are significantly more effective than H2RAs for healing esophagitis of all grades including those refractory to H2RAs. No significant differences in healing esophagitis exist among standard dose of different proton pump inhibitors. Therefore, proton pump inhibitors should be used for patients with esophagitis of all grades.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. WH Wang is the recipient of Visiting Professorship under the Croucher Foundation Chinese Visitorship Scheme of the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Footnotes

Supported by the Gastroenterological Research Fund, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Science Editor Zhu LH and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

References

- 1.Spechler SJ. Epidemiology and natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1992;51 Suppl 1:24–29. doi: 10.1159/000200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castell DO, Johnston BT. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Current strategies for patient management. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:221–227. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong WM, Lai KC, Lam KF, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lam CL, Xia HH, Huang JQ, Chan CK, Lam SK, et al. Prevalence, clinical spectrum and health care utilization of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in a Chinese population: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:595–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston BT, Collins JS, McFarland RJ, Love AH. Are esophageal symptoms reflux-related? A study of different scoring systems in a cohort of patients with heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orlando RC. The pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease: the relationship between epithelial defense, dysmotility, and acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:3S–5S; discussion 5S-7S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holloway RH, Dent J, Narielvala F, Mackinnon AM. Relation between oesophageal acid exposure and healing of oesophagitis with omeprazole in patients with severe reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1996;38:649–654. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.5.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell NJ, Burget D, Howden CW, Wilkinson J, Hunt RH. Appropriate acid suppression for the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1992;51 Suppl 1:59–67. doi: 10.1159/000200917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt RH. Importance of pH control in the management of GERD. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:649–657. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston DA, Wormsley KG. Time of administration influences gastric inhibitory effects of ranitidine. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1137–1140. doi: 10.3109/00365528809090181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merki HS, Halter F, Wilder-Smith C, Allemann P, Witzel L, Kempf M, Roehmel J, Walt RP. Effect of food on H2-receptor blockade in normal subjects and duodenal ulcer patients. Gut. 1990;31:148–150. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon B, Müller P, Marinis E, Lühmann R, Huber R, Hartmann R, Wurst W. Effect of repeated oral administration of BY 1023/SK& amp; F 96022--a new substituted benzimidazole derivative--on pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion and pharmacokinetics in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:373–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teyssen S, Pfuetzer R, Stephan F, Singer MV. Comparison of the effect of a 28-d long term therapy with the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole with the H2-receptor antagonist ranitidine on intragastric pH in healthy human subjects. Gas-troenterology. 1995;108(Suppl 4):A240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1434–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1123_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798–1810. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A. Healing and relapse rates in gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with the newer proton-pump inhibitors lansoprazole, rabeprazole, and pantoprazole compared with omeprazole, ranitidine, and placebo: evidence from randomized clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2001;23:998–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma VK, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing standard clinical doses of omeprazole and lansoprazole in erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:227–231. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards SJ, Lind T, Lundell L. Systematic review of proton pump inhibitors for the acute treatment of reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1729–1736. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallo S, Dibildox M, Moguel A, Di Silvio M, Rodríguez F, Almaguer I, García C. [Clinical superiority of pantoprazole over ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis grade II and III. A prospective, double-blind, double-placebo study. Mexican clinical experience. Mexican Pantoprazole Study Group] Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 1998;63:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulder CJ, Dekker W, Gerretsen M. Lansoprazole 30 mg versus omeprazole 40 mg in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis grade II, III and IVa (a Dutch multicentre trial). Dutch Study Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:1101–1106. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199611000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, Vakil NB, Johnson DA, Zuckerman S, Skammer W, Levine JG. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson NJ, Boyd EJ, Mills JG, Wood JR. Acute treatment of reflux oesophagitis: a multicentre trial to compare 150 mg ranitidine b.d. with 300 mg ranitidine q.d.s. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1989;3:259–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1989.tb00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarty-Dawson D, Sue SO, Morrill B, Murdock RH. Ranitidine versus cimetidine in the healing of erosive esophagitis. Clin Ther. 1996;18:1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(96)80069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson NJ, Laws S, Mills JG, Wood JR. Effect of 3 ranitidine dosage regimens in the treatment of reflux esophagitis - re-sults of a multicenter trial. European J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;3:769–774. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wesdorp IC, Dekker W, Festen HP. Efficacy of famotidine 20 mg twice a day versus 40 mg twice a day in the treatment of erosive or ulcerative reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:2287–2293. doi: 10.1007/BF01299910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon TJ, Berlin RG, Tipping R, Gilde L. Efficacy of twice daily doses of 40 or 20 milligrams famotidine or 150 milligrams ranitidine for treatment of patients with moderate to severe erosive esophagitis. Famotidine Erosive Esophagitis Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:375–380. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pace F, Sangaletti O, Bianchi Porro G. Short and long-term effect of two different dosages of ranitidine in the therapy of reflux oesophagitis. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1990;22:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cloud ML, Offen WW. Nizatidine versus placebo in gastroesophageal reflux disease. A six-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind comparison. Nizatidine Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:865–874. doi: 10.1007/BF01300384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quik RF, Cooper MJ, Gleeson M, Hentschel E, Schuetze K, Kingston RD, Mitchell M. A comparison of two doses of nizatidine versus placebo in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon TJ, Berenson MM, Berlin RG, Snapinn S, Cagliola A. Randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of famotidine 20 mg b.d. or 40 mg b.d. in patients with erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tytgat GN, Nicolai JJ, Reman FC. Efficacy of different doses of cimetidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. A review of three large, double-blind, controlled trials. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:629–634. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruth M, Enbom H, Lundell L, Lönroth H, Sandberg N, Sandmark S. The effect of omeprazole or ranitidine treatment on 24-hour esophageal acidity in patients with reflux esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1141–1146. doi: 10.3109/00365528809090182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bianchi Porro G, Parente F. Topically active drugs in the treatment of peptic ulcers. Focus on colloidal bismuth subcitrate and sucralfate. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:192–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandmark S, Carlsson R, Fausa O, Lundell L. Omeprazole or ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. Results of a double-blind, randomized, Scandinavian multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:625–632. doi: 10.3109/00365528809093923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeitoun P, Desjars De Keranroué N, Isal JP. Omeprazole versus ranitidine in erosive oesophagitis. Lancet. 1987;2:621–622. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)93005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bianchi Porro G, Pace F, Peracchia A, Bonavina L, Vigneri S, Scialabba A, Franceschi M. Short-term treatment of refractory reflux esophagitis with different doses of omeprazole or ranitidine. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:192–198. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardhan KD, Hawkey CJ, Long RG, Morgan AG, Wormsley KG, Moules IK, Brocklebank D. Lansoprazole versus ranitidine for the treatment of reflux oesophagitis. UK Lansoprazole Clinical Research Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sontag SJ, Schnell TG, Chejfec G, Kurucar C, Karpf J, Levine G. Lansoprazole heals erosive reflux oesophagitis in patients with Barrett's oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:147–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.114285000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson M, Sahba B, Avner D, Jhala N, Greski-Rose PA, Jennings DE. A comparison of lansoprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of erosive oesophagitis. Multicentre Investigational Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koop H, Schepp W, Dammann HG, Schneider A, Lühmann R, Classen M. Comparative trial of pantoprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. Results of a German multicenter study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:192–195. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199504000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armbrecht U, Abucar A, Hameeteman W, Schneider A, Stockbrügger RW. Treatment of reflux oesophagitis of moderate and severe grade with ranitidine or pantoprazole--comparison of 24-hour intragastric and oesophageal pH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:959–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soga T, Matsuura M, Kodama Y, Fujita T, Sekimoto I, Nishimura K, Yoshida S, Kutsumi H, Fujimoto S. Is a proton pump inhibitor necessary for the treatment of lower-grade reflux esophagitis? J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:435–440. doi: 10.1007/s005350050292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawano S, Murata H, Tsuji S, Kubo M, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Kanda T, Sato T, Yoshihara H, Masuda E, et al. Randomized comparative study of omeprazole and famotidine in reflux esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:955–959. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armstrong D, Paré P, Pericak D, Pyzyk M. Symptom relief in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized, controlled comparison of pantoprazole and nizatidine in a mixed patient population with erosive esophagitis or endoscopy-negative reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2849–2857. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.4237_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vantrappen G, Rutgeerts L, Schurmans P, Coenegrachts JL. Omeprazole (40 mg) is superior to ranitidine in short-term treatment of ulcerative reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF01798351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Havelund T, Laursen LS, Skoubo-Kristensen E, Andersen BN, Pedersen SA, Jensen KB, Fenger C, Hanberg-Sørensen F, Lauritsen K. Omeprazole and ranitidine in treatment of reflux oesophagitis: double blind comparative trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:89–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6615.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blum AL, Riecken EO, Dammann HG, Schiessel R, Lux G, Wienbeck M, Rehner M, Witzel L. Comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Jansen JM, Festen HP, Meuwissen SG, Lamers CB. Double-blind multicentre comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis. Lancet. 1987;1:349–351. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jansen JB, Van Oene JC. Standard-dose lansoprazole is more effective than high-dose ranitidine in achieving endoscopic healing and symptom relief in patients with moderately severe reflux oesophagitis. The Dutch Lansoprazole Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1611–1620. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farley A, Wruble LD, Humphries TJ. Rabeprazole versus ranitidine for the treatment of erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Raberprazole Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1894–1899. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dettmer A, Vogt R, Sielaff F, Lühmann R, Schneider A, Fischer R. Pantoprazole 20 mg is effective for relief of symptoms and healing of lesions in mild reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:865–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Zyl JH, de K Grundling H, van Rensburg CJ, Retief FJ, O'Keefe SJ, Theron I, Fischer R, Bethke T. Efficacy and tolerability of 20 mg pantoprazole versus 300 mg ranitidine in patients with mild reflux-oesophagitis: a randomized, double-blind, parallel, and multicentre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:197–202. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dehn TC, Shepherd HA, Colin-Jones D, Kettlewell MG, Carroll NJ. Double blind comparison of omeprazole (40 mg od) versus cimetidine (400 mg qd) in the treatment of symptomatic erosive reflux oesophagitis, assessed endoscopically, histologically and by 24 h pH monitoring. Gut. 1990;31:509–513. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.5.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feldman M, Harford WV, Fisher RS, Sampliner RE, Murray SB, Greski-Rose PA, Jennings DE. Treatment of reflux esophagitis resistant to H2-receptor antagonists with lansoprazole, a new H+/K(+)-ATPase inhibitor: a controlled, double-blind study. Lansoprazole Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1212–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sontag SJ, Kogut DG, Fleischmann R, Campbell DR, Richter J, Robinson M, McFarland M, Sabesin S, Lehman GA, Castell D. Lansoprazole heals erosive reflux esophagitis resistant to histamine H2-receptor antagonist therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:429–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lundell L, Backman L, Ekström P, Enander LH, Fausa O, Lind T, Lönroth H, Sandmark S, Sandzén B, Unge P. Omeprazole or high-dose ranitidine in the treatment of patients with reflux oesophagitis not responding to 'standard doses' of H2-receptor antagonists. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vcev A, Stimac D, Vceva A, Rubinić M, Ivandić A, Ivanis N, Horvat D, Volarić M, Karner I. Lansoprazole versus omeprazole in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. Acta Med Croatica. 1997;51:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hatlebakk JG, Berstad A, Carling L, Svedberg LE, Unge P, Ekström P, Halvorsen L, Stallemo A, Hovdenak N, Trondstad R. Lansoprazole versus omeprazole in short-term treatment of reflux oesophagitis. Results of a Scandinavian multicentre trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:224–228. doi: 10.3109/00365529309096076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Castell DO, Richter JE, Robinson M, Sontag SJ, Haber MM. Efficacy and safety of lansoprazole in the treatment of erosive reflux esophagitis. The Lansoprazole Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1749–1757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mee AS, Rowley JL. Rapid symptom relief in reflux oesophagitis: a comparison of lansoprazole and omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:757–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.56198000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mössner J, Hölscher AH, Herz R, Schneider A. A double-blind study of pantoprazole and omeprazole in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis: a multicentre trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:321–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Corinaldesi R, Valentini M, Belaïche J, Colin R, Geldof H, Maier C. Pantoprazole and omeprazole in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis: a European multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:667–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vcev A, Stimac D, Vceva A, Takac B, Ivandić A, Pezerović D, Horvat D, Nedić P, Kotromanović Z, Maksimović Z, et al. Pantoprazole versus omeprazole in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. Acta Med Croatica. 1999;53:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dekkers CP, Beker JA, Thjodleifsson B, Gabryelewicz A, Bell NE, Humphries TJ. Double-blind comparison [correction of Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison] of rabeprazole 20 mg vs. omeprazole 20 mg in the treatment of erosive or ulcerative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. The European Rabeprazole Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:49–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delchier JC, Cohen G, Humphries TJ. Rabeprazole, 20 mg once daily or 10 mg twice daily, is equivalent to omeprazole, 20 mg once daily, in the healing of erosive gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1245–1250. doi: 10.1080/003655200453566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kahrilas PJ, Falk GW, Johnson DA, Schmitt C, Collins DW, Whipple J, D'Amico D, Hamelin B, Joelsson B. Esomeprazole improves healing and symptom resolution as compared with omeprazole in reflux oesophagitis patients: a randomized controlled trial. The Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1249–1258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, Maton P, Breiter JR, Hwang C, Marino V, Hamelin B, Levine JG. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:656–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3600_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bardhan KD, Van Rensburg C. Comparable clinical efficacy and tolerability of 20 mg pantoprazole and 20 mg omeprazole in patients with grade I reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1585–1591. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holtmann G, Bytzer P, Metz M, Loeffler V, Blum AL. A randomized, double-blind, comparative study of standard-dose rabeprazole and high-dose omeprazole in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:479–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kovacs TO, Wilcox CM, DeVault K, Miska D, Bochenek W. Comparison of the efficacy of pantoprazole vs. nizatidine in the treatment of erosive oesophagitis: a randomized, active-controlled, double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2043–2052. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Körner T, Schütze K, van Leendert RJ, Fumagalli I, Costa Neves B, Bohuschke M, Gatz G. Comparable efficacy of pantoprazole and omeprazole in patients with moderate to severe reflux esophagitis. Results of a multinational study. Digestion. 2003;67:6–13. doi: 10.1159/000070201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roufail W, Belsito A, Robinson M, Barish C, Rubin A. Ranitidine for erosive oesophagitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Glaxo Erosive Esophagitis Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1992;6:597–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1992.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Euler AR, Murdock RH, Wilson TH, Silver MT, Parker SE, Powers L. Ranitidine is effective therapy for erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Silver MT, Murdock RH, Morrill BB, Sue SO. Ranitidine 300 mg twice daily and 150 mg four-times daily are effective in healing erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-0673.1996.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Comparison of roxatidine acetate and ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. The Roxatidine Esophagitis Study Group. Clin Ther. 1993;15:283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bate CM, Booth SN, Crowe JP, Hepworth-Jones B, Taylor MD, Richardson PD. Does 40 mg omeprazole daily offer additional benefit over 20 mg daily in patients requiring more than 4 weeks of treatment for symptomatic reflux oesophagitis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:501–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carlsson R, Dent J, Watts R, Riley S, Sheikh R, Hatlebakk J, Haug K, de Groot G, van Oudvorst A, Dalväg A, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care: an international study of different treatment strategies with omeprazole. International GORD Study Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cloud ML, Offen WW, Robinson M. Nizatidine versus placebo in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1735–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cloud ML, Enas N, Humphries TJ, Bassion S. Rabeprazole in treatment of acid peptic diseases: results of three placebo-controlled dose-response clinical trials in duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The Rabeprazole Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:993–1000. doi: 10.1023/a:1018822532736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Earnest DL, Dorsch E, Jones J, Jennings DE, Greski-Rose PA. A placebo-controlled dose-ranging study of lansoprazole in the management of reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD, Narielvala FM, Mackinnon M, McCarthy JH, Mitchell B, Beveridge BR, Laurence BH, Gibson GG. Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:903–912. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Laursen LS, Havelund T, Bondesen S, Hansen J, Sanchez G, Sebelin E, Fenger C, Lauritsen K. Omeprazole in the long-term treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. A double-blind randomized dose-finding study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:839–846. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palmer RH, Miller DM, Hedrich DA, Karlstadt RG. Cimetidine QID and BID in rapid heartburn relief and healing of lesions in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Ther. 1993;15:994–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Richter JE, Bochenek W. Oral pantoprazole for erosive esophagitis: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Pantoprazole US GERD Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3071–3080. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robinson M, Campbell DR, Sontag S, Sabesin SM. Treatment of erosive reflux esophagitis resistant to H2-receptor antagonist therapy. Lansoprazole, a new proton pump inhibitor. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:590–597. doi: 10.1007/BF02064376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sabesin SM, Berlin RG, Humphries TJ, Bradstreet DC, Walton-Bowen KL, Zaidi S. Famotidine relieves symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and heals erosions and ulcerations. Results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. USA Merck Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:2394–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sontag SJ, Hirschowitz BI, Holt S, Robinson MG, Behar J, Berenson MM, McCullough A, Ippoliti AF, Richter JE, Ahtaridis G. Two doses of omeprazole versus placebo in symptomatic erosive esophagitis: the U.S. Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91790-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van Rensburg CJ, Honiball PJ, Grundling HD, van Zyl JH, Spies SK, Eloff FP, Simjee AE, Segal I, Botha JF, Cariem AK, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pantoprazole 40 mg versus 80 mg in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-0673.1996.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lundell L. Prevention of relapse of reflux oesophagitis after endoscopic healing: the efficacy and safety of omeprazole compared with ranitidine. Digestion. 1990;47 Suppl 1:72–75. doi: 10.1159/000200522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.James OF, Parry-Billings KS. Comparison of omeprazole and histamine H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment of elderly and young patients with reflux oesophagitis. Age Ageing. 1994;23:121–126. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Umeda N, Miki K, Hoshino E. Lansoprazole versus famotidine in symptomatic reflux esophagitis: a randomized, multicenter study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20 Suppl 1:S17–S23. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199506001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wilder-Smith C, Halter F, Ernst T, Gennoni M, Zeyen B, Varga L, Roehmel JJ, Merki HS. Loss of acid suppression during dosing with H2-receptor antagonists. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4 Suppl 1:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wilder-Smith CH, Merki HS. Tolerance during dosing with H2-receptor antagonists. An overview. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1992;193:14–19. doi: 10.3109/00365529209096000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Houben GM, Hooi J, Hameeteman W, Stockbrügger RW. Twenty-four-hour intragastric acidity: 300 mg ranitidine b.d., 20 mg omeprazole o.m., 40 mg omeprazole o.m. vs. placebo. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:649–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Blum RA, Shi H, Karol MD, Greski-Rose PA, Hunt RH. The comparative effects of lansoprazole, omeprazole, and ranitidine in suppressing gastric acid secretion. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bell NJ, Hunt RH. Role of gastric acid suppression in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1992;33:118–124. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Landes BD, Petite JP, Flouvat B. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:458–470. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pue MA, Laroche J, Meineke I, de Mey C. Pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole following single intravenous and oral administration to healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;44:575–578. doi: 10.1007/BF02440862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lind T, Rydberg L, Kylebäck A, Jonsson A, Andersson T, Hasselgren G, Holmberg J, Röhss K. Esomeprazole provides improved acid control vs. omeprazole In patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:861–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Holtmann G, Cain C, Malfertheiner P. Gastric Helicobacter pylori infection accelerates healing of reflux esophagitis during treatment with the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meneghelli UG, Boaventura S, Moraes-Filho JP, Leitão O, Ferrari AP, Almeida JR, Magalhães AF, Castro LP, Haddad MT, Tolentino M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pantoprazole versus ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis and the influence of Helicobacter pylori infection on healing rate. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:50–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kromer W. Relative efficacies of gastric proton-pump inhibitors on a milligram basis: desired and undesired SH reactions. Impact of chirality. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2001;36:3–9. doi: 10.1080/003655201753265389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huang JQ, Sumanac K, Hunt RH. Impact of scoring systems on the evaluation of erosive esophagitis (EE) healing? A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(Suppl):W1169. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zeitoun P, Rampal P, Barbier P, Isal JP, Eriksson S, Carlsson R. [Omeprazole (20 mg daily) compared to ranitidine (150 mg twice daily) in the treatment of esophagitis caused by reflux. Results of a double-blind randomized multicenter trial in France and Belgium] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1989;13:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kimmig JM. [Cimetidine and ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis] Z Gastroenterol. 1984;22:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Barbier JP, Haccoun P, Bergmann JF, Arnould B, Hamelin B. [Prognostic factors influencing healing of reflux esophagitis. A controlled trial of omeprazole versus ranitidine. Study group Omega] Ann Gastroenterol Hepatol (Paris) 1993;29:213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Siewert JR, Ottenjann R, Heilmann K, Neiss A, Döpfer H. [Therapy and prevention of reflux esophagitis. Results of a multicenter study with cimetidine. I: Epidemiology and results of acute therapy] Z Gastroenterol. 1986;24:381–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dammann HG, Blum AL, Lux G, Rehner M, Riecken EO, Schiessel R, Wienbeck M, Witzel L, Berger J. [Different healing tendencies of reflux esophagitis following omeprazole and ranitidine. Results of a German-Austrian-Swiss multicenter study] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1986;111:123–128. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1068412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]