Abstract

Introduction:

Brain tumors in children often involve the visual system, but most retrospective series are by neurologists or oncologists. In this study we highlight the ophthalmic findings of outpatient children with visual complaints and/or strabismus who, based on ophthalmic examination, were suspected to and confirmed to harbor intracranial space-occupying lesions by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective case series of children (less than 18 years) who for visual complaints and/or strabismus underwent cranial MRI at a referral eye hospital (2005–2012), which revealed intracranial space-occupying lesions. Exclusion criteria were known preexisting orbital or ocular trauma, ocular tumor, or neurological disease.

Results:

For 26 patients (3 months-17 years; mean 7 years; median 9 years; and 14 boys), the most common clinical presentation was decreased vision with disc pallor (10) or swelling (three). Other presentations were strabismus with disc pallor or swelling (four; two of which were left sixth nerve palsies), acquired esotropia with diplopia (three; one bilateral and two left sixth nerve palsies), acquired exotropia (four; two of which were bilateral third nerve palsies, one of which was left partial third nerve palsy, and one of which was associated with headache), nystagmus (one), and disc swelling with headache (one). Most lesions were in the sellar/suprasellar space (10), posterior fossa (six), or optic nerve/chasm (four).

Conclusions:

The majority of outpatient children diagnosed by ophthalmologists with intracranial space-occupying lesions presented with disc swelling or pallor in the context of decreased vision or strabismus. Two strabismus profiles that did not include disc swelling or pallor were acquired sixth nerve palsy and acquired exotropia (with ptosis (third nerve palsy), nystagmus, or headache).

Keywords: Brain Tumor, Optic Nerve, Pediatric, Strabismus

INTRODUCTION

Brain tumors are the most common cause of childhood death from cancer, and it is of interest to diagnose cases as early as possible. Overall, the commonest first presenting symptoms of brain tumors in children are headache, vomiting, and unsteadiness; however, for 10% of affected children the first presentation is visual difficulties and/or strabismus.1 Although multiple retrospective reviews have highlighted that visual disorders are common before the diagnosis of brain tumors, these studies are typically by neurologists or oncologists rather than ophthalmologists.1,2,3

The purpose of this study is to highlight the ophthalmic findings of outpatient children referred to our institution for ocular complaints and who, based on outpatient ophthalmic examination, were suspected and confirmed to harbor brain tumors by cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional board approval was granted for this study. From the MRI database of the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, we collected medical record numbers of all patients under 18 years who had cranial imaging from 2005 to 2012. These medical records were then reviewed to identify patients whose outpatient MRI testing led to a new diagnosis of brain tumor. Patient age, gender, ophthalmic findings at presentation, and neuroimaging results were recorded. Exclusion criteria were a known history of intracranial pathology before presentation, proptosis, leukocoria, retinoblastoma, and neurofibromatosis.

All MRIs were performed using a 3-Tesla system with a dedicated head coil (Magnetom Allegra 3 Tesla; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The gradient strength was 40 mT/m and slew rate was 400 T/m/s. If sedation was required, it was performed with an oral mixture of 1 mg/kg of promethazine hydrochloride (Centrafarm Services, Etten-Leur, Netherlands). Scout spin echo sagittal T1-weighted MR images were obtained with repetition time/echo time of 600–750/9–11 ms and four acquisitions followed by axial T1-weighted images (repetition time/echo time = 500/14 ms). Transverse T2-weighted MR images were obtained with repetition time/echo time of 2,400–2,800/19–96 ms, field of view of 20 3 22 cm, section thickness of 4 mm, interslice gap of 1–2 mm, and matrix of 320 3 180. Coronal T2- weighted MR images were obtained with repetition time/echo time of 2,400–2,800/19–87 ms, field of view of 20 3 24 cm, section thickness of 4 mm, interslice gap of 1–2 mm, and matrix of 320 3 216. Additional studies (e. g., turbofluid-attenuated inversion recovery or contrast enhancement) were performed as appropriate to better visualize masses. MRIs were interpreted by an experienced radiologist.

RESULTS

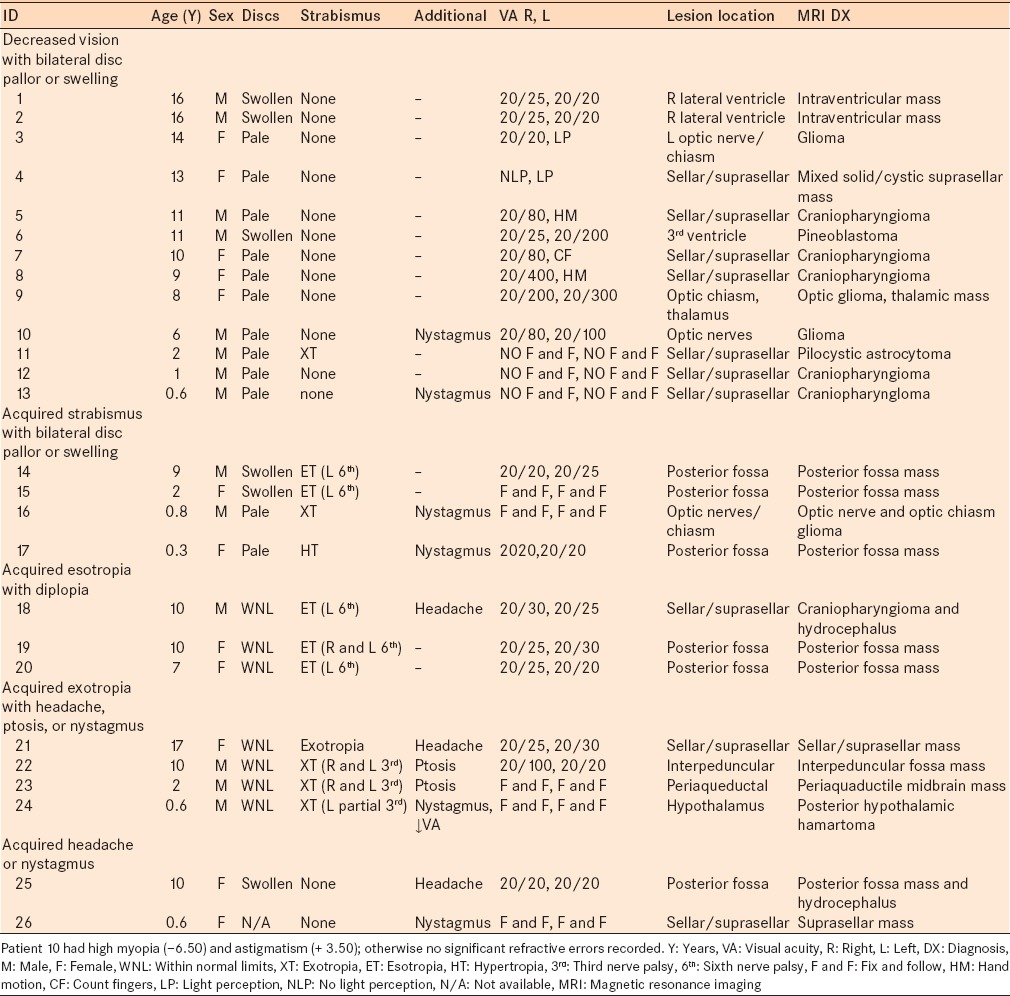

Twenty-six patients were identified (range 3 months-17 years; mean 7 years; median 9 years; and 14 boys). The most common clinical presentation was decreased vision with disc pallor (10; two with nystagmus and one with exotropia) or disc swelling (three). Acquired strabismus with disc pallor or swelling was the second most common presentation (four; two of which were left sixth nerve palsies). The remaining children presented with acquired esotropia with diplopia (three; one bilateral and two left sixth nerve palsies), acquired exotropia (four; two of which were bilateral third nerve palsies, one of which was a left partial third nerve palsy, and one of which was associated with headache), acquired nystagmus (one), or disc swelling with headache (one). Most lesions were in the sellar/suprasellar space (10), posterior fossa (six), or optic nerve/chasm (four). Symptoms and tumor location are summarized in Table 1. A clinical example is provided in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patients

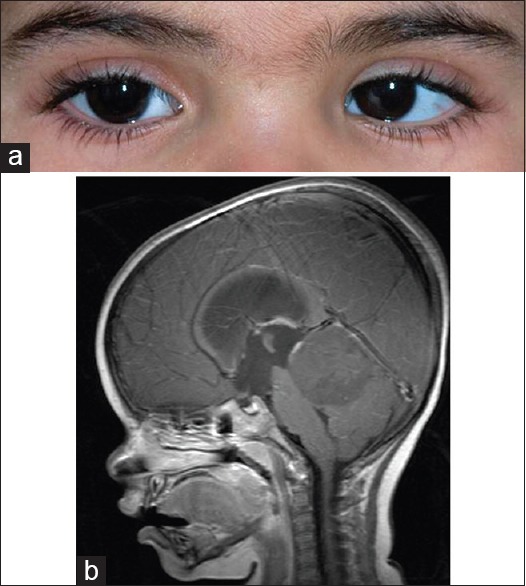

Figure 1.

Patient 15: This two-year-old girl presented with left sixth nerve palsy and bilateral swollen optic discs and was found to have a posterior fossa mass. Primary position alignment (a) and neuroimaging results (b) are shown

DISCUSSION

In our outpatient referral pediatric ophthalmology setting, disc pallor or swelling was the single most recurrent clinical sign of children who were subsequently diagnosed with space-occupying intracranial lesions (18/26), often in the context of decreased vision (13/18) or acquired sixth nerve palsy (2/18). The eight cases that did not include optic disc swelling or pallor were cases of acquired sixth nerve palsy in older children (three, age 7–10 years), acquired third nerve palsy (three), and acquired nystagmus (one). Intracranial lesions were most frequently sellar/parasellar (10), in the posterior fossa (six), or in the optic nerve/chiasm (four).

Disc pallor or swelling from pediatric brain tumor can be from tumor intrinsic to the optic nerve/chiasm, tumor contiguous to the optic nerve/chiasm, or tumor elsewhere causing nonlocalizing increased intracranial pressure.4,5 Sellar/parasellar lesions accounted for seven cases with disc pallor or swelling in our series, five of which were diagnosed neuroradiologically as craniopharyngiomas. If space-occupying intracranial lesion is ruled out as a cause for disc pallor or swelling, other causes to be evaluated for by further investigations include optic neuritis, hereditary optic neuropathy, developmental anatomical abnormalities (e. g., craniosynostosis), infiltrative disease (e. g., sarcoidosis), vascular disease, and pseudotumor cerebri.

Acquired third nerve or sixth nerve palsy was the second most common presentation in our series. Acquired third nerve palsies were from direct compressive effect on the third nerve pathway in all three cases. Diplopia was not a documented presenting complaint; this was likely related to ipsilateral lid ptosis and the young ages in two of the three affected patients (2 and 0.6 years). Acquired sixth nerve palsies in our series were typically from a lesion in the posterior fossa, rather than from a direct localized compressive effect, and 2/5 cases also had bilateral disc pallor or swelling. Sixth nerve palsy from remote rather than direct local tumor effect may be from increased intracranial pressure and/or brainstem displacement causing mechanical trauma along the course of the sixth nerve. Interestingly, all four unilateral cases were on the left side, as is also common in Duane syndrome6 and idiopathic recurrent sixth nerve palsy,7 suggesting there may be an anatomical predisposition to injury on this side. If space-occupying compressive lesion is ruled out in an acquired pediatric third or sixth nerve palsy case, other entities to consider include myasthenia gravis, migraine, local inflammation/infection, and local ischemia/infarction. In addition, all children with acquired strabismus should undergo cycloplegic refraction to rule out uncorrected refractive error as a factor in their strabismus.

Acquired nystagmus was the presentation for one case of suprasellar mass in an infant for whom the optic nerve appearance was not clearly documented (Case 26). While acquired nystagmus typically warrants neuroimaging, it is important to realize that congenital/infantile nystagmus in the absence of optic nerve pallor is by itself not an indication for neuroimaging; clinical and electrophysiological studies of the retina should be done before considering neuroimaging in an otherwise healthy child with infantile nystagmus and no evidence for optic nerve dysfunction/pallor.8

In general, posterior fossa tumors are more common than supratentorial tumors in children, although in infants the latter tend to be more frequent.9 Consistent with this trend, in our series posterior fossa lesions were more common in older children and sellar/parasellar lesions were common in infants, although there were several older children with sellar/parasellar lesions [Table 1].

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature, that is, only data recorded in medical records were available. There may have been signs and symptoms that patients were experiencing and were not recorded. Also, we only report on children who actually had space-occupying intracranial lesions, that is, we do not have data on the percentage of cases with signs such as optic nerve pallor or swelling that did not have such lesions. Moreover, we lack follow-up as to what happened to these patients after the MRI diagnosis, as after radiological diagnosis they were referred to and managed by outside facilities. In addition, there may have been cases of brain tumors that were seen at our institute but did not have neuroimaging, and thus were missed. However, despite these limitations, we do define the most common ophthalmic presentations of outpatient children referred to our pediatric ophthalmology unit who were suspected and shown to harbor intracranial space-occupying lesions based on the ophthalmology examination. The majority of outpatient children diagnosed by ophthalmologists with intracranial space-occupying lesions presented with disc swelling or pallor in the context of decreased vision or strabismus. Two common strabismus profiles that did not include disc swelling or pallor were acquired sixth nerve palsy and acquired exotropia (with ptosis (third nerve palsy), nystagmus, or headache).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilne SH, Ferris RC, Nathwani A, Kennedy CR. The presenting features of brain tumours: A review of 200 cases. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:502–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.090266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilne S, Collier J, Kennedy C, Koller K, Grundy R, Walker D. Presentation of childhood CNS tumours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:685–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi N, Kidokoro H, Miyajima Y, Fukazawa T, Natsume J, Kubota T, et al. How do the clinical features of brain tumours in childhood progress before diagnosis? Brain Dev. 2010;32:636–41. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirtschafter JD, Rizzo FJ, Smiley BC. Optic nerve axoplasm and papilledema. Surv Ophthalmol. 1975;20:157–89. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(75)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee AG, Chau FY, Golnik KC, Kardon RH, Wall M. The diagnostic yield of the evaluation for isolated unexplained optic atrophy. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:757–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan AO, Oystreck DT, Wilken K, Akbar F. Duane retraction syndrome on the Arabian Peninsula. Strabismus. 2007;15:205–8. doi: 10.1080/09273970701632023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yousuf SJ, Khan AO. Presenting features suggestive for later recurrence of idiopathic sixth nerve paresis in children. J AAPOS. 2007;11:452–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shammari MA, Elkhamary SM, Khan AO. Intracranial pathology in young children with apparently isolated nystagmus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49:242–6. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20120221-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodsky MC. Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of systemic and intracranial disease. In: Brodsky MC, editor. Pediatric Neuro-Ophthalmology. Ch. 11. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 503–96. [Google Scholar]