Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose was to determine the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) in Bahrain.

Designs and Methods:

premature infants (gestation age ≤32 weeks, birth weight ≤1500 g) admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Salmaniya Medical Complex were examined based on a predetermined screening protocol. The first examination was performed at 4–6 weeks of age, from January 1, 2002 to December 3, 2011. Data were collected on the type and incidence of each of ROP, birth weight, and age. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Results:

A total of 1795 premature infants comprised the study population. Group 1 (<1000 g), and Group II (1000–1500 g), included 700 (39%) and 1095 (61%) infants. ROP was detected in 367 (20.4%) infants (95% CI = 18.6–22.3). The proportions of stage III ROP, stage III threshold disease requiring laser retinal photocoagulation and stage IV were 19%, 6%, and 1%, respectively. There were 68 (18.5%) infants with stage III ROP, 21 infants with Stage III ROP with threshold, and 5 infants with stage IV ROP requiring vitreoretinal surgery. There were 203 (80%) infants with a birth weight <1000 g. Birth weight of <1000 g was significantly associated to ROP [OR = 2.3 (95% CI = 1.8–2.9)].

Conclusion:

One-fifth of premature infants had ROP in Bahrain. Birth weight <1000 g was a risk factor for ROP.

Keywords: Incidence, Prematurity, Retinopathy

INTRODUCTION

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a disease that affects low birth-weight infants in which the retinal blood vessels fail to develop properly. This results in rapidly progressive and abnormal structural changes in the eye that can causes blindness from retinal detachment, macular folds, refractive amblyopia, or strabismic amblyopia.1 In 1987, a joint statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Ophthalmology, and American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus was released recommending ROP screening by an experienced ophthalmologist for all infants with a birth weight <1500 g or with gestational age <32 weeks, as well as for select infants with a birth weight between 1500 and 2000 g believed to be at high risk by the attending neonatologist.2 Despite advances in detection and treatment, ROP continues to be a leading cause of childhood blindness and visual impairment worldwide in extremely premature infants with low birth weight.2,3,4

Retinopathy of prematurity is a leading cause of childhood blindness in the Middle East. Advances in neonatal care, improved access to healthcare, and improved delivery of healthcare especially related to maternal and child healthcare has resulted in better survival of preterm children. However, these improvements have resulted in an increase in the rate of ROP and severity at presentation.5 Screening premature infants for ROP at Salmaniya Medical Complex (SMC) in Bahrain began as a program in 1996 for all premature infants with a birth weight ≤1600 and a gestational age ≤32 weeks. The present study reports the incidence of ROP from January 2002 to January 2011 among all premature infants admitted to the infant care unit at SMC. This Medical Complex is the main government secondary and tertiary hospital in Bahrain to asses the applicability of the current ROP screening criteria and to compare our data with international data.

DESIGNS AND METHODS

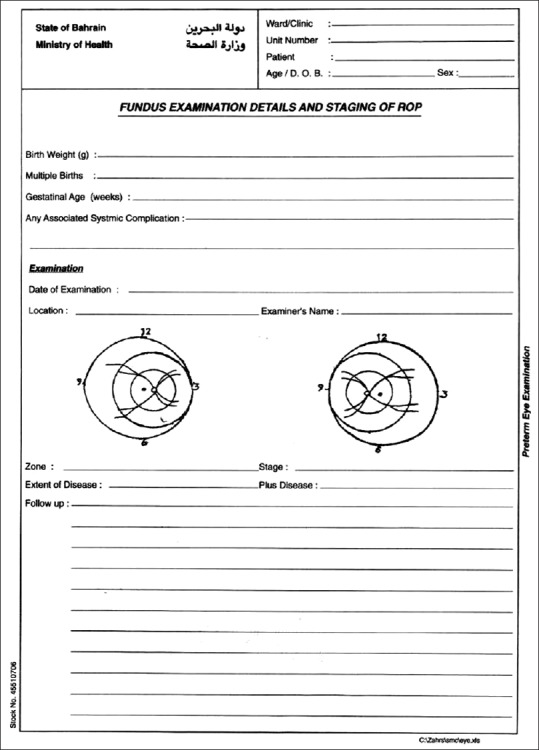

This retrospective study, including all infants with a birth weight ≤1500 and a gestational age ≤32 weeks who were admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at SMC and were examined 4–6 weeks after birth from 2002 to 2011 using the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Guidelines (1997).2 This was performed by reviewing the screening forms attached to the medical record [Figure 1]. Data were collected via chart review on gestational age, birth weight, clinical information, ROP stage, ROP zone, and the presence of other disease. Newborns who died before 6 weeks of age were excluded.

Figure 1.

Fundus examination details and staging of ROP screening form

A Pediatric Ophthalmologist (1, 3) performed all examinations. Data were collected by searching the NICU database, which included clinical information about neonates and ROP. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the secondary care research committee. Infants were included in this study if they were born at SMC or any of the Ministry of Health maternity hospitals and transferred and admitted to the NICU at SMC, and were examined and monitored by a Pediatric Ophthalmologist.

The International classification of ROP and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations were used for classification of the findings.6 The findings were classified according to the maximum stage of ROP in either eye.

Examinations were performed at the main neonatology unit in Bahrain, which has four consultant neonatologists, a capacity of 50 neonates, and a NICU capacity of seven cases. The neonatology unit strictly implements oxygen management and monitoring with a target of 85% to 92% oxygen saturation. Oxygen saturations are maintained at stable lower levels and avoiding fluctuations for very-low-birth-weight infants. If ROP was not noted, eye examinations were performed until vascularization reached zone 3 of the retina.

It was the responsibility of the medical and nursing staff to ensure that the examinations were scheduled at the appropriate ages based on the guidelines. To examine the peripheral retina, amethocaine 1%, cyclopentolate 0.5%, or tropicamide 0.5% was instilled with phenylephrine 2.5%, and a sterile eyelid specula and scleral depressor were used as necessary [Figure 2]. A binocular indirect ophthalmoscope was used with a handheld lens [Figure 3]. Ophthalmologists also followed any other local criteria for maintaining sterility.

Figure 2.

Preparations of the premature baby for fundus examination

Figure 3.

Examination of Premature baby with Indirect ophthalmoscope

The Pediatric Ophthalmologist documented the vascularity of the retina and the stage of ROP on the ROP screening form, and indicated the timing of the follow-up. Incidence of ROP in the study population was determined and analyzed on the basis of birth weight.7

For analysis, follow-up examinations for those with ROP were screened at intervals indicated by the severity of the disease. Infants were monitored until a diagnosis of ROP was established as ROP or another disease. More frequent examinations to monitor the course of ROP were performed. The CRYO-ROP trial presented a “threshold” of treatment for ROP which was defined as at least five clock hours of contiguous, or eight cumulative clock hours of stage 3 ROP in zone I or II in the presence of plus disease.8 Infants were classified according to the birth weight into Group 1 who were <1000 g, and Group II, who were between 1000 and 1500 g.

The data were collected using Microsoft Excel® software (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). The data were transferred to Statistical Package for Social Studies (SPSS 22) (IBM, Chicago, USA) for analysis. Univariate analysis was performed using a parametric method for calculating frequencies and percentage proportions of qualitative variables. For continuous variables mean and standard deviations were calculated. To compare ROP risk in subgroups, Odd's ratio and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study population included 1829 premature infants of which 1795 (98.6%) infants were included in the study because their data in the patient charts were complete. There were 700 [38.9%]) infants in Group 1 and 1095 [61.1%]) infants in Group II.

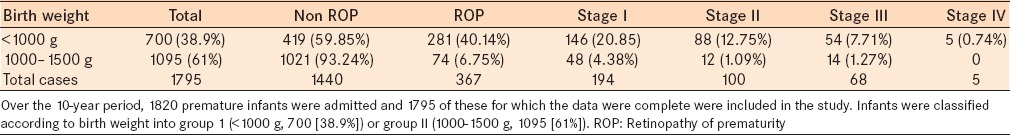

ROP at any stage was detected in 367 of 1795 infants. This leads to an incidence of 20.4%. Stage III ROP was detected in 68/1795 (3.8%) infants and represents 18.5% of the total number of ROP cases. Stage III threshold disease requiring laser retinal photocoagulation was detected in 21/367 (5.7%) infants, and 5/367 (1.4%) infants progressed to stage IV ROP which required vitreoretinal surgery. Eighty percent (293/367) of the ROP cases occurred in neonates with BW <1000 g [Table 1].

Table 1.

Stages of ROP by birth weight

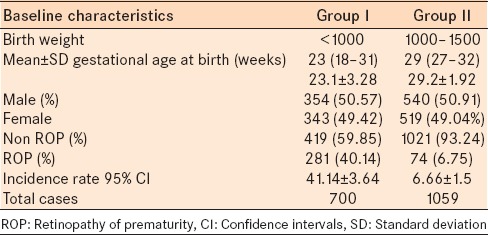

The average estimated gestational age (EGA) at birth was 25 weeks (range, 18 weeks to 32 weeks). The mean birth weight was 1047 g (range, 594–1500 g) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Stages of ROP by birth weight and gestational age

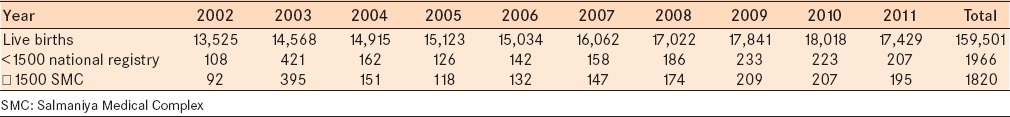

The ratio of premature infants ≤1500 g per live births (159,501) was 1.2% from 2002 to 2011.

The total number of premature cases ≤1500 admitted to the neonatal unit at SMC represents a mean of 92.6% of all premature infants born in Bahrain during the study period from 2002 to 2011. The overall incidence of any ROP among all newborn infants in Bahrain during the study period was 1/434 (0.2%) infants. Mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower among infants with ROP [Table 3].9

Table 3.

Distribution of live births per year in the national registry and premature infants in Bahrain and at the SMC

DISCUSSION

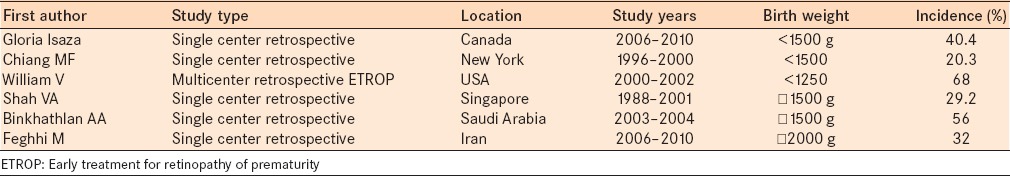

Our study represents the incidence of ROP in the largest study population in Bahrain to date. It comprises 75% of the deliveries in Bahrain. The incidence of ROP in previous studies varies by region from 22% to 56% [Table 4].10,11,12,13,14,15,16 The incidence of ROP in the current study is similar to previous reports. However, comparison to other studies is tenuous at best as some studies included neonates with a birth weight <1250 g. This could result underestimating the incidence of ROP compared to our study. In addition, other studies have included pre-threshold criteria based on the Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity (ETROP) study,16 which treated some patients sooner than the defined threshold for CRYO-ROP with good results. This effectively changed the threshold for treatment. The most important change is that treatment can now be considered sooner without regard to the number of clock hours involved. The new criteria defined by ETROP and the clinical algorithm shows that in most circumstances,17 peripheral retinal ablation should be considered for any eye with type I ROP, zone I ROP with plus disease (regardless of stage), zone I ROP with stage 3 disease (with or without plus disease), zone II ROP, stage 2 or 3, with plus disease.

Table 4.

Data comparison between different studies

Gilbert et al.18 compared gestational age and birth weight between countries with low, moderate, and high levels of development. In highly developed countries, they found that all infants with severe ROP had a mean gestational age <26 weeks and a mean birth weight <800 g.

Mean gestational age and birth weight of infants with severe ROP in the present study were 25 weeks and 730 g, respectively. Gestational age and birth weight were significantly correlated with ROP in the present study. Birth weight and gestational age in the ROP group were significantly lower than in the non-ROP group.

These findings are consistent with other studies that birth weight and gestational age are important factors associated with ROP. In some recent studies, extremely premature infants with lower gestational age had a higher incidence of type 1 ROP. No infant with a gestational age >26 weeks at birth or birth weight >1000 g had type 1 ROP.19 Birth weight may not influence the incidence of type 1 ROP in extremely premature infants.20Şahin et al. was found no association between type 1 ROP and BW in extremely preterm infants with a GA of <28 weeks.21

ROP is a potentially avoidable cause of blindness in children. The proportion of blindness resulting from ROP varies greatly among countries and is influenced both by levels of neonatal care (in terms of availability, access, and neonatal outcomes) and the availability of effective screening. Gilbert et al.22 suggest that the population of infants who develop severe ROP in highly developed countries differs from those who are affected in less well-developed countries, given the complex interaction between case mix, neonatal care, and survival rates, as well as variation in screening practices and follow-up rates of discharged infants, and retreatment programs.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the study was conducted among in patients in the NICU and thus could misrepresent the general incidence of ROP. Second, premature infants were referred to neonatal units at other Ministry of Health hospitals once they were stabilized systemically, and although most of the infants returned to our hospital for follow-up, we were unable to access complete documentation. Third, many factors are involved in the development and progression of ROP. We did not study risk factors related to presence or absence of ROP.

Advances in electronic documentation and follow-up that were recently introduced at the hospital will provide more clinical information and a better infrastructure for prospective studies to investigate the incidence of ROP in relation to the risk factors.

CONCLUSION

The incidence of ROP was 20.4%. ROP cases were associated with birth weight <1000 g. The incidence of ROP in Bahrain in 2002–2011 correlates with other published data.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudanko SL, Fellman V, Laatikainen L. Visual impairment in children born prematurely from 1972 through 1989. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1639–45. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 1997;100:273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. A joint statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:888–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, et al. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: Findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:15–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandekar R, Kishore H, Mansu RM, Awan H. The status of childhood blindness and functional low vision in the Eastern Mediterranean region in 2012. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:336–43. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.142273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. The Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1130–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030908011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalam K, Lin S, Murthy R, Brar V, Gupta S, Radhakrishnan R. Evaluation of modified retinopathy of prematurity screening guidelines using birth weight as the sole inclusion criterion. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;18:214–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.84048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Multicenter Trial of Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity: Ophthalmological outcomes at 10 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1110–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Statistical Data, Ministry of Health, Health Statistics 2011. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.bh/EN/aboutMOH/Information/Statistics.aspx .

- 10.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, et al. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: Findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:15–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaza G, Arora S, Bal M, Chaudhary V. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity and risk factors among premature infants at a neonatal intensive care unit in Canada. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2013;50:27–32. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20121127-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang MF, Arons RR, Flynn JT, Starren JB. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity from 1996 to 2000: Analysis of a comprehensive New York state patient database. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.William V. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: Findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah VA, Yeo CL, Ling YL, Ho LY. Incidence, risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity among very low birth weight infants in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binkhathlan AA, Almahmoud LA, Saleh MJ, Srungeri S. Retinopathy of prematurity in Saudi Arabia: Incidence, risk factors, and the applicability of current screening criteria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:167–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.126508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feghhi M, Altayeb SM, Haghi F, Kasiri A, Farahi F, Dehdashtyan M, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity and risk factors in the South-Western region of Iran. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:101–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.92124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Good VW. Final results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity (Etrop) randomized trial. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2004;102:233–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert C, Rahi J, Eckstein M, O’Sullivan J, Foster A. Retinopathy of prematurity in middle-income countries. Lancet. 1997;350:12–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isaza G, Arora S. Incidence and severity of retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teed RG, Saunders RA. Retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants. J AAPOS. 2009;13:370–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahin A, Sahin M, Türkcü FM, Cingü AK, Yüksel H, Cinar Y, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants. ISRN Pediatr. 2014;2014:134347. doi: 10.1155/2014/134347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert C, Fielder A, Gordillo L, Quinn G, Semiglia R, Visintin P, et al. Characteristics of infants with severe retinopathy of prematurity in countries with low, moderate, and high levels of development: Implications for screening programs. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e518–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]