Abstract

Background:

To assess the short-term efficacy and safety of corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) in preventing the progression of keratoconus (KCN).

Materials and Methods:

This randomized controlled clinical trial enrolled 26 patients diagnosed with bilateral progressive KCN and were eligible for CXL. In each patient, one eye was randomly selected for treatment, and the contralateral eye served as the control. The patients underwent CXL with riboflavin drops and ultraviolet radiation in the treated eye. One year follow-up data are presented. Postoperatively, patients were assessed for progression of KCN, visual changes, and other findings. The main outcome measures were maximum simulated keratometry (K-max), best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), and average simulated keratometry. P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results:

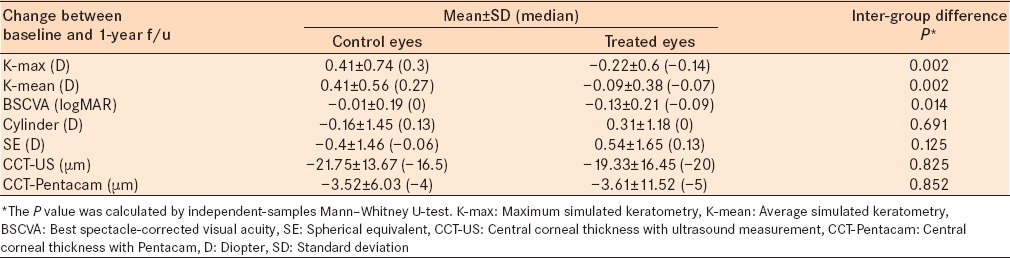

In the treated eyes, the mean K-max values decreased by 0.22 D at 1-year postoperatively and increased by 0.41 D in the control group. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). BSCVA improved slightly (a decrease of 0.13 LogMAR) and decreased slightly in the control group (a 0.01 LogMAR increase). The difference between groups was statistically significant (P = 0.014). There was no decrease in visual acuity attributable to complications of CXL in the treated eyes. At 1-year, the keratometry in 3 (12%) treated eyes increased by more than 0.50 D and were considered cases of failed treatment.

Conclusion:

Preliminary and 1-year results indicate CXL can halt the progression of KCN in most cases without causing serious complications.

Keywords: Collagen Cross-Linking, Keratoconus, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial

INTRODUCTION

Keratoconus (KCN) is a noninflammatory, degenerative corneal condition in which the cornea shows signs of ectasia and progressive thinning. As this ectasia progresses, corneal irregularities form that decrease visual quality precluding spectacle correction in most cases. Although the condition is usually bilateral, the severity in each eye may differ. The incidence of KCN is reported to be around 1 in 2000.1 However, advanced diagnostic equipment is allowing identification of early stages of KCN and the incidence seems to be higher than previous estimates.2 KCN usually begins in adolescence and in many cases progresses into moderate and advanced forms that are associated with severe visual impairment.3,4

Options for improving vision in KCN patients include prescription spectacles, hard contact lenses, and surgical procedures such as implantation of intracorneal ring segments and corneal transplantation. Until recently, there was no treatment to stop or slow the progression of KCN.

In the early 90 s, researchers at Dresden University, Germany, investigated methods to prevent or slow the progression of KCN by increasing corneal tensile strength. Their efforts lead to the introduction of corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL). The method is based on the observation that creation of cross-links between adjacent collagen molecules can increase the tensile strength of the cornea, and therefore, slow or halt the progress of KCN.5 As a morphologic correlate of the crosslinking process, significant increases in corneal collagen diameter have been observed after cross-linking.6 The concepts of CXL originated from physiologic findings and an understanding of the changes that occur during the aging process and diabetes mellitus. The number of cross-links between collagen fibrils increase with age, and this may somehow explain why the progression of KCN halts at older age (physiologic cross-linking).7 In addition, an increase in CXL in diabetics is due to glycosylation of the cornea and results in increased corneal tensile strength. This may also explain the very low incidence of KCN in diabetics (pathologic cross-linking).8

In CXL, riboflavin (Vitamin B2) drops are instilled on the cornea to saturate the corneal stroma. Subsequently, the cornea is exposed to ultraviolet (UV) rays. UV radiation causes riboflavin molecules to release free oxygen radicals that lead to irreversible covalent cross-linking between adjacent collagen molecules.9 Studies have demonstrated that CXL increases the tensile strength of the cornea10,11 and clinical experience has shown that it can halt progression of KCN.2,12 However, most clinical studies that have been published to date lack control groups, and only one prospective, randomized controlled study has been reported.13

We performed a prospective, randomized, controlled study to evaluate the results and complications of CXL associated with the treatment of progressive KCN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study enrolled patients presenting at the Noor Eye Hospital or Noor Eye Clinic, Tehran, Iran. A total of 35 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled, but only data from 26 cases with complete preoperative examinations and presented at their follow-up visits up to 1-year were used in the analysis. The nine patients, who were not included in the final analysis, missed their follow-up visits for unknown reasons or did not present within the time frame for their final visit which was 12–14 months postoperatively. All patients underwent a thorough informed consent procedure that included a discussion of the treatment and procedures in the study. All patients signed consent forms before enrollment into the study. Inclusion criteria were age between 15 and 40 years, confirmed bilateral KCN based on clinical and topography findings, bilateral minimum corneal thickness of 400 μm as measured with the Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) maximum keratometry of 60 D in each eye based on Pentacam readings, and evidence that KCN is progressing. Both eyes of each patient had to meet the criteria indicative of KCN progression over the previous 12 months. Evidence for KCN progression was determined by chart review, and previous spectacles or base curve of contact lenses. KCN was diagnosed as “progressive” if at least one of the following changes were verified:

Increased simulated maximum keratometry (sim max K) by at least 1.0 D, based on corneal topography or ≥1.0 D increase in the curvature of the steep meridian based on keratometer measurements

Increased cylinder by at least 1.0 D, based on the manifest refraction

Loss of ≥2 lines of best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA) attributable solely to the progression of KCN.

The exclusion criteria were corneal scarring in either eye, previous eye surgery, ocular surface or tear problems, and the coexistence of ocular pathology other than KCN.

In each patient, one eye was randomly selected for treatment using a computerized random number table, and the contralateral eye served as the control. All eyes underwent complete examinations before treatment, and at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after CXL. Examinations included uncorrected visual acuity, refraction, BSCVA, slit lamp exam, fundoscopy, Scheimpflug imaging with the Pentacam (Ocular Optikgeräte GmbH, Germany), and pachymetry with an ultrasound pachymeter (Nidek, US 1800, Echoscan, NIDEK Co. Ltd. Gamagori, Japan). Patients were advised to discontinue wearing hard contact lenses at least three weeks prior to the procedure and soft contact lenses at least 3 days before.

The selected eye underwent CXL treatment within 1-month after preliminary preoperative examinations. We used a method similar to that proposed by Wollensak et al.12 Local anesthesia was achieved by instilling one drop of tetracaine hydrochloride 0.5% (Sina Daru, Iran), three times at 5 min intervals. For the procedure, the lid speculum was placed, and then the epithelium was removed in an 8 mm area of the central cornea. Then we instilled one drop of riboflavin 0.1% in 20% dextran (Streuli pharmaceuticals, Uznach, Switzerland) onto the stroma once every 3 min for 30 min (a total of 10 drops). Once this stage was completed, the patient was examined at the slit lamp to observe the presence of riboflavin and yellow tindall in the anterior chamber. Subsequently the UV-X (IROC, Zürich, Switzerland) was used to irradiate 370 nm UV light, 9 mm in diameter onto the cornea from a distance of 5 cm.

Before each treatment session, the UV-X was calibrated to ensure a radiation intensity of 3 mw/cm2. The cornea was exposed to UV for 30 min while simultaneously instilling riboflavin drops every 3 min. At the end of this procedure, the corneal surface was irrigated with sterile BSS, and then covered with a soft bandage contact lens (Night and Day, Bausch and Lomb, CA, USA). One drop of chloramphenicol 0.5% (Sina Daru, Iran) was instilled and the patient was instructed to topical chloramphenicol four times daily in addition to betamethasone 0.1%, four times daily, and preservative-free artificial tears (hypromelose) as needed. Patients were examined on the first and third posttreatment day. On the 3rd day, the contact lens would be removed provided that epithelial healing was complete. After the lens removal, chloramphenicol was discontinued, and betamethasone was continued twice daily for one week. Betamethasone was not prescribed for a longer duration to mitigate complications such as increased intraocular pressure and also based on the observation that the majority of previous studies limited steroid use to 1 to 2 weeks only. Cases with incomplete epithelial healing on the 3rd day were examined daily until complete reepithelialization.

Main outcome measures during follow-up were BSCVA, the maximum simulated keratometry (K-max) and mean keratometry (K-mean) based on Pentacam readings. The mean, median, and standard deviation were calculated for K-max, K-mean, BSCVA, and spherical equivalent. The independent-samples Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare data in the two groups. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

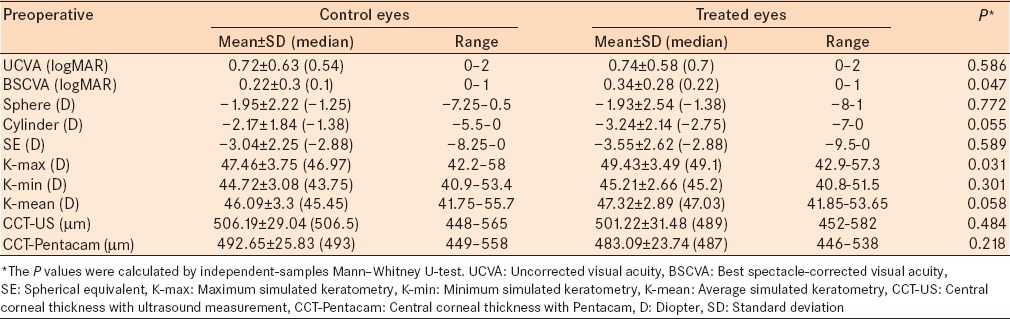

A total of 52 eyes of 26 patients were studied. The mean age of all the patients was, 25.6 ± 5.1 years (range, 15–37 years), 30.8% (n = 8) were male, and 69.2% (n = 18) were female. Table 1 summarizes clinical findings in the treatment and control groups at baseline. Before CXL, the studied variables were comparable in the two groups, and there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, K-mean and BSCVA.

Table 1.

Preoperative vision, refraction, and topographic parameters of eyes in the treatment and control groups

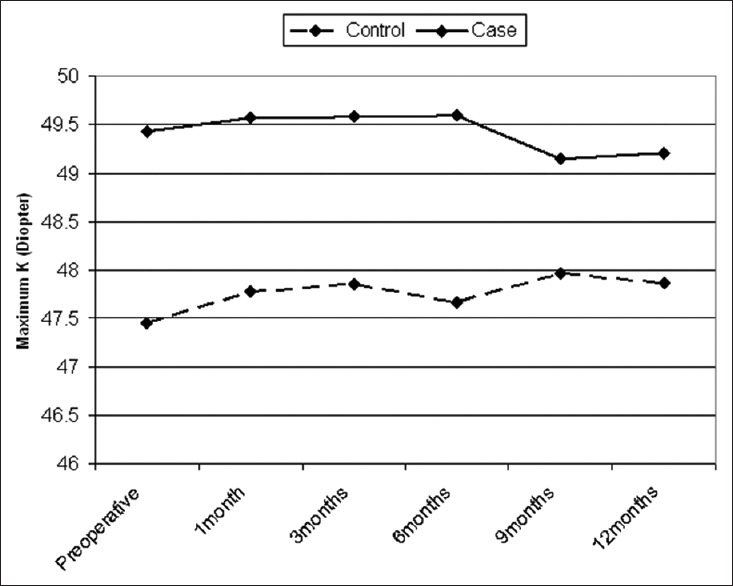

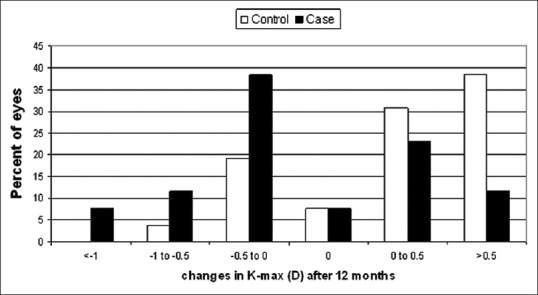

The outcomes for K-max are presented in Figure 1. The K-max decreased 0.22 ± 0.6 D in the treated group and increased 0.41 ± 0.74 D in the control group [Figure 1]. The change in K-max from before treatment to the 1-year follow examination was statistically significantly different between groups (P = 0.002). The K-max decreased by more than 0.50 D in more than 20% of the treated eyes, in 9.0%, the decrease was more than 1.0 D, and in 7.7% of eye, there was no change in K-max [Figure 2]. The increase in K-max was greater in the control group [Figure 2]. There were 12% of eyes in the treatment group that were classified as a failed treatment (>0.5 D increase in K-max) and 38.5% of the eyes in the control group had an increase in K-max >0.5 D.

Figure 1.

Comparison of changes in maximum keratometry readings over time in the two groups

Figure 2.

Changes in maximum keratometry in the two groups after 1-year

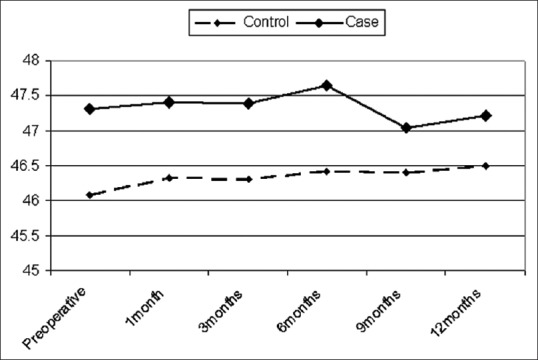

The K-mean improved by 0.1 D from 47.3 D to 47.2 D in the treatment group while the mean increased from 46.1 D to 46.5 D in the control group [Figure 3]. Changes in K-mean from before CXL to 1-year after CXL were statistically significantly different between groups (P = 0.002) [Figure 3]. Table 2 summarizes the changes in BSCVA, cylinder and corneal thickness 1-year after CXL and the differences between groups.

Figure 3.

Changes in average keratometry readings in the two groups over time

Table 2.

Change of main outcome measures between baseline and 1-year follow-up

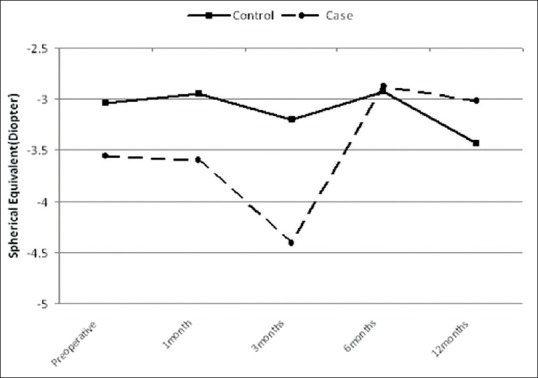

Figure 4 presents the changes in spherical equivalent for both groups. The spherical equivalent improved after treatment compare to before CXL in the treated group and deteriorated in the control group. There was 0.54 ± 1.65 D less myopia in the treated group compared to 0.4 ± 1.46 D more myopia in the control group (P = 0.125).

Figure 4.

Comparison of spherical equivalent values in the two groups over time

Reepithelialization was complete by the 3rd day in all treated eyes except one which took 5 days. Grade 1+ or 2+ (Hanna grading)14 corneal (stromal) haze was present in all treated eyes. Corneal haze was similar to post-photorefractive keratectomy eyes. The corneal haze resolved between 3 and 6 months after CXL and did not persist in any eye. The demarcation line15 was visible in the corneal stroma at about two-thirds of the thickness in 20 of 26 treated eyes during the 1st month after CXL.

DISCUSSION

In many countries, KCN is the leading cause of keratoplasty, and in others, it is among the most common causes.16,17 Considering the visual results of keratoplasty, which are far from ideal, and the prevalence of KCN, it is not surprising that CXL has garnered significant attention so quickly after introduction in clinical practice.

The main biomechanical feature of KCN is reduced tensile strength.18 CXL increases corneal rigidity and halts the progression of the condition. Increased corneal rigidity has been confirmed by in-vitro10,11 and in-vivo experiments on human eyes.2,12 In fact, the mode of action in CXL had never been achieved in previous treatment modalities.

One of the main obstacles to evaluating CXL outcomes in halting the progress of KCN arises from the unpredictable behavior and speed of progression between eyes of a patient.1,3,18 Accurate knowledge of KCN progression in each eye can be achieved by studying its clinical trend over a long time, however, these data are typically unavailable. The inclusion criteria in this study were chosen to overcome this obstacle, and we followed a paired analysis approach; the untreated eye of each patient served as the control for the contralateral treated eye. We ensured that KCN was progressing bilaterally and randomized the grouping of eyes into treatment and control groups. This approach may minimize the confounding effect of different progression rates in different eyes. To eliminate the potential effect of hard contact lenses, imaging with the Pentacam was performed at least 3 weeks after patients discontinued contact lens wear.

The first clinical report concerning CXL was published in 2003 by Wollensak et al., who studied 6 month results in 23 patients.12 The mean reduction in K-max in their study was 1.4 D, and they had no cases of failed treatment. Hoyer et al.19 reported 3-years results in 153 eyes, with a mean reduction of 4.0 D in K-max and a 2% (3 eyes) treatment failure. Similar results have been reported from Italy,2,20 France,21 and India.22 All these reports concern case series without controls. Wittig-Silva et al. published the first and only randomized controlled study of CXL.13 They13 found the outcomes in the treatment and control cases were statistically significantly different. Average K-max changes at 1-year were −1.45 D and 1.28 D in the treatment and control groups respectively, and were no failed treatments.13 However, they compared different people, not contralateral eyes.13 Coskunseven et al.23 treated one eye with CXL and used the contralateral eye as the control in 29 patients. In each patient, they23 chose the eye with more advanced KCN for treatment, and there was no randomization. After a mean period of 9 months, the K-max in the treated group decreased by 1.57 D and did not change in the control group.23

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the effect of CXL in which contralateral eyes are compared, and case selection was randomized. At 1-year, the mean change in K-max was −0.22 D in the treated group and 0.41 D in the control group. In 3 cases (12%), CXL was not successful, and KCN progressed despite treatment. Overall, our findings concur with the literature. CXL can slow or halt the progress of KCN in the treated eye; however, some treatment failures should be expected. Similar to other studies, we observed a decrease in K-max (>0.5 D) in one-third of treated eyes, and this was associated with a slight improvement in BSCVA. Furthermore, the majority of untreated eyes (control eyes) demonstrated increases in K-max, further progression of KCN and decreased BSCVA.

We encourage more prospective controlled trials to determine if CXL can become part of the standard treatment for progressive KCN. Currently, these studies are rare.24 The longest reported follow-up has been 6 years.25 Our study provides some information on the safety and efficacy of this new treatment option, but more extensive studies with longer follow-up are necessary.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship Noor Ophthalmology Research Center, Noor Eye Hospital.

Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kok YO, Tan GF, Loon SC. Review: Keratoconus in Asia. Cornea. 2012;31:581–93. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31820cd61d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caporossi A, Baiocchi S, Mazzotta C, Traversi C, Caporossi T. Parasurgical therapy for keratoconus by riboflavin-ultraviolet type A rays induced cross-linking of corneal collagen: Preliminary refractive results in an Italian study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:837–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson AE, Hayes S, Hardcastle AJ, Tuft SJ. The pathogenesis of keratoconus. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:189–95. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazirani J, Basu S. Keratoconus: Current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:2019–30. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S50119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spoerl E, Wollensak G, Dittert DD, Seiler T. Thermomechanical behavior of collagen-cross-linked porcine cornea. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218:136–40. doi: 10.1159/000076150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wollensak G, Wilsch M, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Collagen fiber diameter in the rabbit cornea after collagen crosslinking by riboflavin/UVA. Cornea. 2004;23:503–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000105827.85025.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert L, Legeais JM, Robert AM, Renard G. Corneal collagens. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2001;49:353–63. doi: 10.1016/s0369-8114(01)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seiler T, Huhle S, Spoerl E, Kunath H. Manifest diabetes and keratoconus: A retrospective case-control study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238:822–5. doi: 10.1007/s004179900111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollensak G. Crosslinking treatment of progressive keratoconus: New hope. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:356–60. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233954.86723.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McQuaid R, Cummings AB, Mrochen M. The theory and art of corneal cross-linking. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:416–9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.116069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Stress-strain measurements of human and porcine corneas after riboflavin-ultraviolet-A-induced cross-linking. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:1780–5. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-a-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:620–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittig-Silva C, Whiting M, Lamoureux E, Lindsay RG, Sullivan LJ, Snibson GR. A randomized controlled trial of corneal collagen cross-linking in progressive keratoconus: Preliminary results. J Refract Surg. 2008;24:S720–5. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20080901-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna KD, Pouliquen YM, Savoldelli M, Fantes F, Thompson KP, Waring GO, 3rd, et al. Corneal wound healing in monkeys 18 months after excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy. Refract Corneal Surg. 1990;6:340–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seiler T, Hafezi F. Corneal cross-linking-induced stromal demarcation line. Cornea. 2006;25:1057–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000225720.38748.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanavi MR, Javadi MA, Sanagoo M. Indications for penetrating keratoplasty in Iran. Cornea. 2007;26:561–3. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318041f05c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang PC, Klintworth GK, Kim T, Carlson AN, Adelman R, Stinnett S, et al. Trends in the indications for penetrating keratoplasty, 1980–2001. Cornea. 2005;24:801–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000157407.43699.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loughnan MS, Snibson GR. Understanding keratoconus. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2001;29:339. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoyer A, Raiskup-Wolf F, Spörl E, Pillunat LE. Collagen cross-linking with riboflavin and UVA light in keratoconus. Results from Dresden. Ophthalmologe. 2009;106:133–40. doi: 10.1007/s00347-008-1783-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinciguerra P, Albè E, Trazza S, Rosetta P, Vinciguerra R, Seiler T, et al. Refractive, topographic, tomographic, and aberrometric analysis of keratoconic eyes undergoing corneal cross-linking. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fournié P, Galiacy S, Arné JL, Malecaze F. Corneal collagen cross-linking with ultraviolet - A light and riboflavin for the treatment of progressive keratoconus. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2009;32:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal VB. Corneal collagen cross-linking with riboflavin and ultraviolet - A light for keratoconus: Results in Indian eyes. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:111–4. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.44515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coskunseven E, Jankov MR, 2nd, Hafezi F. Contralateral eye study of corneal collagen cross-linking with riboflavin and UVA irradiation in patients with keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:371–6. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090401-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koller T, Seiler T. Therapeutic cross-linking of the cornea using riboflavin/UVA. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2007;224:700–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raiskup-Wolf F, Hoyer A, Spoerl E, Pillunat LE. Collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet - A light in keratoconus: Long-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]