Abstract

To describe two cases of herpetic keratitis after corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) for progressive keratoconus. An 18-year-old male and a 21-year-old male with rapidly progressive keratoconus were treated with CXL. Postoperatively, on the 6th and 9th days respectively, a dendritic ulcer was observed in the treated eye. The corneal sensation was significantly diminished compared to the fellow eye. Both patients had no prior history of herpetic eye disease or cold sores. The keratitis improved dramatically over the following days after initiation of antiviral therapy. At 4 months, the visual acuity was stable without corneal scarring. Herpetic keratitis could be induced by CXL even in patients with no history of previous herpetic eye disease. Early diagnosis and proper treatment can facilitate the successful management of this rare but important complication.

Keywords: Cross-linking, Cross-linking Complication, Herpetic Keratitis, Keratoconus

INTRODUCTION

Corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A (UV-A) is currently the only treatment that can halt or delay the progression of keratoconus. In this technique, the combined action of riboflavin and UV-A rays is utilized to increase the corneal strength and integrity by polymerization of the stromal fibers.1,2 With the widespread adoption of this technique, reports of side-effects and complications are increasing.3,4,5,6,7 In this case report, we present two patients who developed clinically diagnosed herpetic keratitis in the early postoperative period after CXL.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

An 18-year-old male was referred to our institute for progressive bilateral keratoconus. There was no previous history of intraocular or corneal surgery, herpetic keratitis, autoimmune disease or systemic connective tissue disease.

The uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 20/100 in the right eye and 20/70 in the left eye. The best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA) was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. The cornea was clear in both eyes. The central pachymetry was 436 μm oculus dexter (OD) and 457 μm oculus sinister (OS). Topography showed inferior steepening bilaterally. Topography after 6 months showed the progression of keratoconus (defined as either an increase in the manifest cylinder of 1 D or greater or an increase in the steepest keratometry by 1 D or greater). The recommended treatment was CXL with riboflavin and UV-A to stabilize the cornea. The patient underwent a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of CXL with the surgeon and signed a written informed consent in accordance with institutional guidelines based on the Declaration of Helsinki.

Corneal collagen cross-linking was performed under sterile conditions. The right eye was anesthetized with proparacaine 0.5% (Alcaine; Alcon Inc., Hünenberg, Switzerland). A 9.0 mm diameter of the corneal epithelium was mechanically removed using a surgical blade, and riboflavin 0.1% solution was instilled repeatedly for approximately 30 min. Penetration of the cornea and presence of riboflavin in the anterior chamber (riboflavin shielding) was confirmed by slitlamp examination. UV-A irradiation was performed using an optical system (UV-X illumination system version 1000; Avedro Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with a light source consisting of an array of UV diodes (365 nm) with a potentiometer in series to allow regulation of voltage. Irradiance of the cornea with 3 mw/cm2 was performed for 30 min. During treatment, the riboflavin solution was applied every 2 min and drops of the physiological saline solution were instilled in between to moisten the cornea. After treatment, a bandage contact lens was placed on the cornea. Postoperative medication included predinsolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte; Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) four times daily tapered over 4 weeks, ofloxacin 0.3% (Optiflox; Jamjoom Pharma, Oman) four times daily for 2 weeks, and cyclopentolate 1% TID for 1-week. The patients were also advised to instill preservative free artificial tears (Tears Natural Free; Alcon Inc., Hünenberg, Switzerland). The patient was examined daily until the epithelium healed completely. The postoperative course was unremarkable for the right eye.

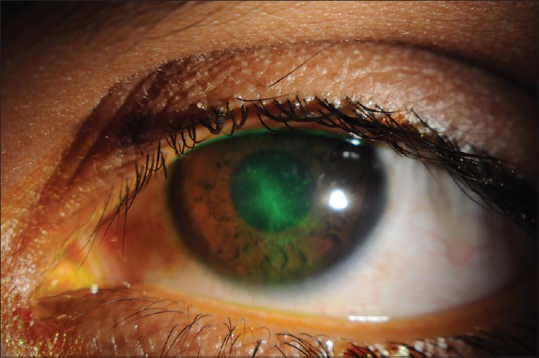

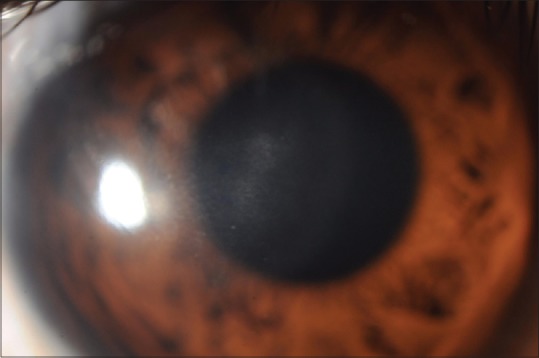

The same procedure was repeated after 3 months for the left eye. On the 5th day, slow re-epithelialization was observed. On the 7th postoperative day, the patient presented with a geographic epithelial defect with dendritic edges without iritis. Corneal sensation was decreased in comparison to the right eye. Topical corticosteroid was discontinued, and the patient was started on ganciclovir (Virgan gel, 1.5 mg/g; Thea Pharma, Wetteren, Belgium) five times daily for 2 weeks then three times daily for 2 weeks. After 2 days of initiation of topical antiviral therapy, the geographic ulcer dramatically improved and re-epithelialized [Figure 1]. Topical corticosteroid drops were resumed after healing of the epithelial defect. All medications were slowly tapered over the following weeks. Four months later, a mild central corneal opacity remained but the UCVA recovered to preoperative levels without any recurrence of keratitis [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Corneal dendrite stained with fluorescein after 2 days of treatment (photo was not taken at the beginning of the treatment)

Figure 2.

Mild corneal haze after 4 months of treatment

Case 2

A 21-year-old male presented with progressive bilateral keratoconus. The patient was healthy without any history of systemic diseases or previous ocular surgery. The UCVA was 20/70 and BSCVA was 20/30 in the right eye. The UCVA was 20/50 and BSCVA was 20/25 in the left eye. The corneas were clear bilaterally. The central pachymetry was 473 μm OD and 511 μm OS. Topography showed bilateral inferior paracentral steepening. The patient was diagnosed with keratoconus and was scheduled for regular follow-up. Progression was diagnosed after 6 months based on topographic changes. The patient was booked for bilateral corneal CXL. The patient underwent a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of CXL with the surgeon and signed a written informed consent in accordance with institutional guidelines based on the Declaration of Helsinki.

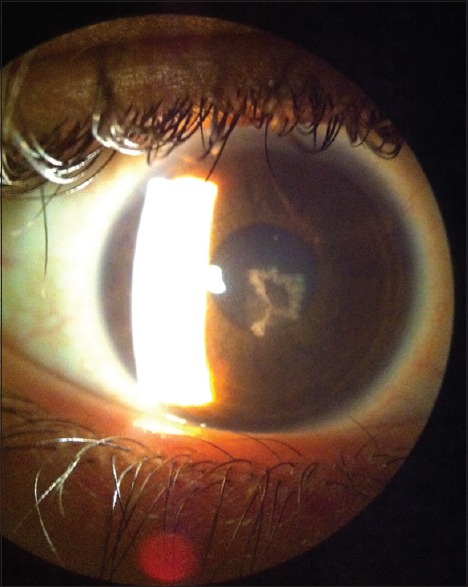

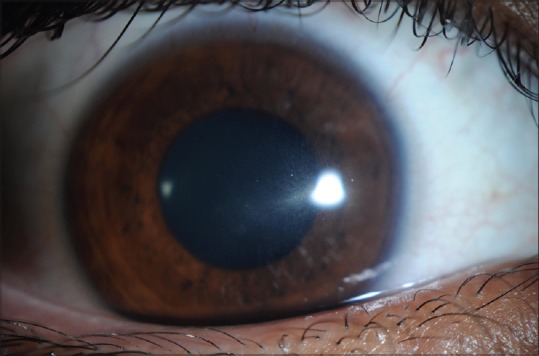

Corneal crosslinking of the right eye was performed under sterile conditions using the same technique and the same postoperative medication that was described above. On the 6th day, slow re-epithelialization was observed. On the ninth postoperative day, the patient presented with dendritic epithelial keratitis without iritis [Figure 3]. Corneal sensation was decreased in comparison to the right eye. Topical corticosteroids were discontinued, and the patient was started on ganciclovir Virgan ((Ganciclovir 0.15%) Eye Gel, Thea Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Newcastle, UK) eye gel five times daily. After 2 days of treatment, the dendritic ulcer had re-epithelialized. Topical corticosteroid drops 4 times a day were resumed. All medications were slowly tapered during the following month. Four months later, a faint central corneal opacity remained [Figure 4]. The BSCVA recovered to preoperative levels without any recurrence of the dendritic ulcer.

Figure 3.

Dendritic epithelial keratitis (on the 9th day postcorneal collagen cross-linking)

Figure 4.

Mild corneal haze after 4 months of treatment

DISCUSSION

Corneal collagen cross-linking with riboflavin and UV-A is becoming the accepted method for the treatment of progressive keratoconus.3 It has been shown to increase effectively the biomechanical strength of the cornea and halt the progression of keratoconus. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been reported after emotional stress, trauma, fever, and laser surgery.4 These established clinical triggers are thought to be mediated by the adrenergic and sensory nervous systems. Exposure to UV light can also induce oral and genital herpes in humans and ocular herpes in animal models.5,6,8 The Herpetic Eye Study Group9 studied many triggers including, psychological stress, systemic infection, sunlight exposure, menstrual cycle, and contact lens wear. None of these factors were significantly associated with recurrence of herpetic keratitis. In this case report, we describe two patients who developed typical dendritic herpetic epithelial keratitis after CXL treatment. In our cases, the presumed clinical diagnosis of herpetic keratitis was supported by the clinical appearance of the lesions, delayed epithelial healing, decreased corneal sensation and the rapid response to antiviral treatment. In our cases, we typically follow the patient carefully until the epithelium is intact; delayed healing raises the suspicion of secondary infective keratitis. Therefore, we propose that it is important to closely monitor the patient until there is complete reepithelialization. Also, in cases of delayed healing secondary infective keratitis should be ruled out. UV-A light may be a potent stimulus to trigger reactivation of latent HSV infections, even in patients with no history of clinical ocular herpes infection. Significant corneal epithelial/stromal trauma or actual damage of the corneal nerves could be the mechanism for HSV reactivation. The use of topical corticosteroids with an epithelial defect is an additional risk factor for infectious keratitis of any etiology.

In our cases, both patients did not have a history of previous herpetic eye disease or cold sores, which concur with Kyminonis's et al. case reports. Yuksel et al.10 also reported a no previous history of herpetic keratitis or cold sores. Primary HSV keratitis frequently manifests as a nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection and is recognized as HSV <5% of the time. Latent infection of the trigeminal ganglion may occur in the absence of recognized primary infection, with reactivation occurring later as recurrent HSV infection in any branch of the trigeminal nerve. Secondary HSV infection can affect almost any ocular tissue including: The eyelid, conjunctiva, cornea, iris, trabecular meshwork, and retina. Secondary HSV can occur as a self-limited disease, and patients may not seek medical advice in some episodes.

Our patients presented later than in previous reports.7,10 There were no recurrences in both patients for 4 months, which was not been documented in previous case reports.7,10 Their diagnosis was confirmed with polymerase chain reaction tear analysis for HSV. Despite the rapid closure of the epithelium within 2 days and initiation of topical steroids, they also noted a mild central corneal scar at 2 months which were similar to our patients. As CXL is becoming increasingly popular for the treatment of progressive keratoconus, new side-effects and complications are emerging. Herpetic keratitis may be triggered by CXL, even in cases with no history of the disease. Close follow-up of patients after CXL appears to be important, as early diagnosis and proper treatment can facilitate the successful management of herpetic epithelial keratitis and prevent further potential sequelae. The retrospective nature of this case report is a limitation. Whenever there is a question regarding the etiology of an infectious keratitis, we recommend laboratory analysis to support the clinical diagnosis of HSV keratitis and rule out similar herpes zoster virus keratitis. The prompt response to antiviral therapy supports a herpes virus as the cause of keratitis in these cases but does not exclude the possibility of herpes zoster keratitis.

In conclusion, CXL with riboflavin and UV-A can induce herpes keratitis with or without iritis. Early diagnosis with prompt treatment should result in good vision. Prophylactic systemic antiviral treatment in patients with a history of the herpetic disease after CXL with UV-A might decrease the possibility of recurrence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon MO, Steger-May K, Szczotka-Flynn L, Riley C, Joslin CE, Weissman BA, et al. Baseline factors predictive of incident penetrating keratoplasty in keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:923–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-a-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:620–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wollensak G. Crosslinking treatment of progressive keratoconus: New hope. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:356–60. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233954.86723.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou YC, Chen CC, Wang IJ, Hu FR. Recurrent herpetic keratouveitis following YAG laser peripheral iridotomy. Cornea. 2004;23:641–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000114123.63670.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perna JJ, Mannix ML, Rooney JF, Notkins AL, Straus SE. Reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus infection by ultraviolet light: A human model. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:473–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rooney JF, Straus SE, Mannix ML, Wohlenberg CR, Banks S, Jagannath S, et al. UV light-induced reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 2 and prevention by acyclovir. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:500–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kymionis GD, Portaliou DM, Bouzoukis DI, Suh LH, Pallikaris AI, Markomanolakis M, et al. Herpetic keratitis with iritis after corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1982–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludema C, Cole SR, Poole C, Smith JS, Schoenbach VJ, Wilhelmus KR. Association between unprotected ultraviolet radiation exposure and recurrence of ocular herpes simplex virus. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:208–15. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psychological stress and other potential triggers for recurrences of herpes simplex virus eye infections. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1617–25. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.12.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuksel N, Bilgihan K, Hondur AM. Herpetic keratitis after corneal collagen cross-linking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A for progressive keratoconus. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:513–5. doi: 10.1007/s10792-011-9489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]