Abstract

A case of frontal fibrosing alopecia with nail involvement is presented. Nail involvement provides evidence for underlying lichen planus, and that the disease represents a rather generalized than localized process. Favorable response of the scalp condition to oral dutasteride points to an inflammatory reaction on the background of androgenetic alopecia.

Keywords: Androgenetic alopecia, dutasteride, frontal fibrosing alopecia, lichen planus, nail involvement

INTRODUCTION

Frontal fibrosing alopecia represents a peculiar condition originally described by Kossard in women in the postmenopause.[1] The condition presents with a symmetric, marginal alopecia along the frontal and frontotemporal hairline, often with concomitant thinning or complete loss of eyebrows. Affected women typically present with the complaint of asymptomatic, progressive recession of their frontal hairline. The affected scalp skin is pale and smooth with loss of follicular orifices, often perifollicular erythema and follicular keratinization is observed marking the underlying inflammatory process. Since Kossard's original description in 1994, the number of cases has exploded exponentially worldwide, while its etiology has remained obscure. Based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies, Kossard et al. eventually interpreted the condition as a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris.[2] Trüeb and Torricelli's original report of oral lichen planus in a patient with postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia further supported the evidence that the condition actually may represent a variant of lichen planus.[3] Herein we report on lichen planus-typical nail involvement in frontal fibrosing alopecia.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old female patient presented with a history of asymptomatic progressive recession of the frontal hairline and loss of eyebrows. She was formerly unsuccessfully treated with topical minoxidil by her local dermatologist.

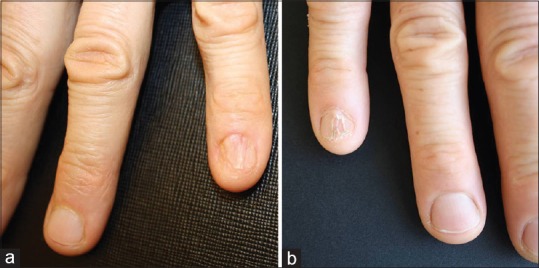

Clinical examination revealed a marginal alopecia along the fronto-temporal hairline and loss of eyebrows [Figure 1]. The affected scalp skin was pale and smooth, loss of follicular orifices, perifollicular erythema, and follicular keratinization. The nail plate of the right fifth digit demonstrated ridging, fissuring and superficial fragility [Figure 2a], the left fifth digit initial atrophy and scarring with pterygium formation [Figure 2b].

Figure 1.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia: symmetric, marginal alopecia along the frontal and frontotemporal hairline, with concomitant thinning or complete loss of eyebrows

Figure 2.

Lichen planus-typical nail involvement (a) with superficial nail fragility, and (b) pterygium formation

A hair pluck (trichogram) demonstrated 23% telogen roots and 33% anagen roots without hair root sheaths in the frontal pluck, with normal figures (telogen rate of 9%, and 18% anagen roots without hair root sheaths) in the occipital pluck, consistent with androgenetic alopecia.

Treatment was started with 0.5 mg oral dutasteride and 0.05% topical clobetasole propionate with reduction of signs of follicular inflammation by dermoscopic examination at 3 months follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus is a primary inflammatory disease of the skin, which may affect the mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails. When the hair follicle is selectively targeted, it is also referred to as follicular lichen planus or lichen planopilaris.

The cause of lichen planus has largely remained unknown, but it is understood to represent a T-cell mediated autoimmune reaction with an unknown initial trigger, with striking analogies to cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. This autoimmune process triggers apoptosis of epithelial cells. When a triggering agent is occasionally identified, this is termed a lichenoid reaction rather than lichen planus. Recognized triggering agents include: Drugs (gold salts, beta-blocking agents, antimalarials, thiazide diuretics), amalgam tooth fillings (in lichen planus of the buccal mucosa), and hepatitis B or C infection.

Since Kossard's original description of postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia in 1994,[1] Zinkernagel and Trüüeb reported in 2000 yet another form of fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution affecting the centroparietal area of the scalp, histologically with a lichenoid type of follicular inflammation and fibrosis.[4] The authors addressed the question how the lichenoid tissue reaction is generated around the individual androgenetic hair follicle, and came up with the proposition that follicles with some form of damage or malfunction might express cytokine profiles that attract inflammatory cells to assist in damage repair or in the initiation of apoptosis-mediated organ deletion. Alternatively, an as yet unknown antigenic stimulus from the damaged or malfunctioning hair follicle might initiate a lichenoid tissue reaction in the immunogenetically susceptible individual.

Ultimately, in 2005 Olsen acknowledged existence of clinically significant inflammatory phenomena and fibrosis in androgenetic alopecia and proposed the term “cicatricial pattern hair loss,”[5] while in 2010 Kossard suggested that frontal fibrosing alopecia may hold the key to understanding the complex relationship of pattern alopecia, sex-related differences, and triggers for autoimmune follicular destruction.[6]

Eventually, frontal fibrosing alopecia has been recognized to represent a rather generalized than localized process of inflammatory scarring alopecia,[7,8] with extension beyond the frontotemporal hair line, loss of eyebrows and of eyelashes, loss of peripheral body hair, mucous membrane involvement, and finally, nail involvement.

Moreover, cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been reported to be capable of mimicking frontal fibrosing alopecia,[9,10,11] suggesting that the pattern of clinical disease presentation might be more specific for the condition than the underlying inflammatory autoimmune reaction. Nevertheless, lichen planus remains the single most frequent pathology underlying frontal fibrosing alopecia, and associated lichenoid mucous membrane or nail involvement may provide clues to the underlying pathology.

There is no cure for lichen planus or frontal fibrosing alopecia, but a number of treatments have been proposed to control symptoms or halt disease progression.[12,13] Where androgenetic alopecia represents a co-morbid condition, topical minoxidil and oral dutasteride may be of benefit,[14,15,16] in addition to topical and/or systemic anti-inflammatory treatment modalities (topical or intralesional corticoseroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and oral doxycycline, hydroxychloroquine, or mycophenolate mofetil, respectively).

The presented case of frontal fibrosing alopecia with nail involvement provides the evidence for underlying lichen planus, whereas favorable response to oral dutasteride may be related to co-morbid androgenetic alopecia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: This case report represents an integral part of Melanie Macpherson's traineeship in trichology at the Center for Dermatology and Hair Diseases Professor Trüeb

REFERENCES

- 1.Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: A frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trüeb RM, Torricelli R. Lichen planopilaris simulating postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia (Kossard) Hautarzt. 1998;49:388–91. doi: 10.1007/s001050050760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinkernagel MS, Trüeb RM. Fibrosing alopecia in a pattern distribution: Patterned lichen planopilaris or androgenetic alopecia with a lichenoid tissue reaction pattern? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:205–11. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen EA. Female pattern hair loss and its relationship to permanent/cicatricial alopecia: A new perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:217–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kossard S. Post-menopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. In: Kossard S, editor. Aging Hair. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. p. 33ff. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armenores P, Shirato K, Reid C, Sidhu S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia associated with generalized hair loss. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:183–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew AL, Bashir SJ, Wain EM, Fenton DA, Stefanato CM. Expanding the spectrum of frontal fibrosing alopecia: A unifying concept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:653–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffney DC, Sinclair RD, Yong-Gee S. Discoid lupus alopecia complicated by frontal fibrosing alopecia on a background of androgenetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:217–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan S, Fenton DA, Stefanato CM. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lupus overlap in a man: Guilt by association? Int J Trichology. 2013;5:217–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.130420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Rei M, Pirmez R, Sodré CT, Tosti A. Coexistence of frontal fibrosing alopecia and discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp in 7 patients: Just a coincidence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jdv.12642. DOI: 10.1111/jdv.12642. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banka N, Mubki T, Bunagan MJ, McElwee K, Shapiro J. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective clinical review of 62 patients with treatment outcome and long-term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1324–30. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, Arias-Santiago S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Garnacho-Saucedo G, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoulis A, Georgala, Bozi E, Papadavid E, Kalogeromitros D, Stavrianeas N. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: Treatment with oral dutasteride and topical pimecrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:580–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgala S, Katoulis AC, Befon A, Danopoulou I, Georgala C. Treatment of postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia with oral dutasteride. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:157–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladizinski B, Bazakas A, Selim MA, Olsen EA. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective review of 19 patients seen at Duke University. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]