Abstract

Background

Despite the large number of published papers analyzing the prognostic role of Ki-67 in NSCLC, it is still not considered an established factor for routine use in clinical practice. The present meta-analysis summarizes and analyses the associations between Ki-67 expression and clinical outcome in NSCLC patients.

Methods

PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase databases were searched systematically using identical search strategies. The impacts of Ki-67 expression on survival in patients with NSCLC and NSCLC subtypes were evaluated. Furthermore, the association between Ki-67 expression and the clinicopathological features of NSCLC were evaluated.

Results

In total, 32 studies from 30 articles met the inclusion criteria, involving 5600 patients. Meta-analysis results suggested that high Ki-67 expression was negatively associated with overall survival (OS; HR = 1.59, 95 % CI 1.35-1.88, P < 0.001) and disease-free survival (DFS; HR = 2.21, 95 % CI 1.43-3.42, P < 0.001) in NSCLC patients. Analysis of the different subgroups of NSCLC suggested that the negative association between high Ki-67 expression and OS and DFS in Asian NSCLC patients was stronger than that in non-Asian NSCLC patients, particularly in early-stage (Stage I-II) adenocarcinoma (ADC) patients. Additionally, while high expression was more common in males, smokers, and those with poorer differentiation, there was no correlation between high Ki-67 expression and age or lymph node status. Importantly, significant correlations between high Ki-67 expression and clinicopathological features (males, higher tumor stage, poor differentiation) were seen only in Asian NSCLC patients.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis indicated that elevated Ki-67 expression was associated with a poorer outcome in NSCLC patients, particularly in early-stage Asian ADC patients. Studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to validate our findings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1524-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ki-67, Meta-analysis, Non-small cell lung cancer, Prognostic value

Background

Lung cancer (LC) is often fatal and is very common worldwide. It has been reported that the overall 5-year survival rate of lung cancer patients was ~16 %, and that it was < 70 % even in patients diagnosed at stage I [1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), of which adenocarcinoma (ADC) and non-ADC (including squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC), large cell lung carcinoma (LCC), and bronchial gland carcinoma (BGC)) account for the majority of cases, represents almost 80 % of primary LC cases. Although the treatment of LC is becoming more individualized, there is an urgent need for reliable prognostic factors to predict clinical outcome and to more precisely stratify the group of patients with poorer outcomes.

Ki-67 is expressed in proliferating cells and has been used in clinical practice as an index to evaluate proliferative activity in NSCLC and other cancers [2, 3]. Moreover, several studies have suggested that high Ki-67 expression in a tumor is a strong prognostic factor in NSCLC [4–7]. However, despite the large number of published papers analyzing the prognostic role of Ki-67 in NSCLC, it is still not considered an established factor for routine use in clinical practice [8, 9]. Although a large meta-analysis involving 17 studies published in 2004 showed that high expression of Ki-67 was associated with a poorer overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) 1.56, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.30–1.87), it did not evaluate the association between Ki-67 expression and disease-free survival. Most importantly, because of the limited number of studies and patients included, it did not examine high Ki-67 expression in Asian patients [2]. Thus, a further meta-analysis investigation is needed to delineate the relationship between Ki-67 expression and prognostic significance in NSCLC more clearly.

In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to explore the relationship between Ki-67 expression and its prognostic value in NSCLC. Associations between Ki-67 expression and the clinicopathological features of NSCLC, including age, gender, smoking status, lymph node status, and tumor differentiation, were also evaluated.

Methods

The protocol, including the objective of our analysis, criteria for study inclusion/exclusion, assessment of study quality, primary outcome, and statistical methods, was in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (“PRISMA”) statement (Additional files 1 and 2) [10].

Study selection

The PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase databases were searched systematically for relevant articles published up to November 1, 2014. Search terms included Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (‘Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung’ or ‘Carcinoma, Non Small Cell Lung’ or ‘Carcinomas, Non-Small-Cell Lung’ or ‘Lung Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell’ or ‘Lung Carcinomas, Non-Small-Cell’ or ‘Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinomas’ or ‘Carcinoma, Non-Small Cell Lung’ or ‘Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma’ or ‘Non Small Cell Lung Carcinoma’ or ‘NSCLC’), Ki-67 (‘Ki-67’ or ‘Ki67’ or ‘MIB-1’ or ‘MIB 1’ or ‘proliferative index’), prognosis, survival, and outcome, in all possible combinations. Using these parameters, we filtered out all the eligible articles and looked through their reference lists for additional studies. The systematic literature search was undertaken independently by two reviewers (SW and ZW) and ended in November 2014. Disagreements were determined through consensus with a third reviewer (CL). Authors of the eligible studies were contacted for additional data relevant to this meta-analysis, as necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the primary studies were 1) inclusion of patients with a distinct NSCLC diagnosis by pathology, 2) measurement of Ki-67 expression using immunohistochemistry (IHC) in primary NSCLC tissue, 3) investigation of the relationship between Ki-67 expression and overall survival (OS) or disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with NSCLC and availability of valid survival data either provided directly or that could be calculated indirectly, and 4) publication in the English language. When authors had several publications or reported on the same patient population, only the most recent or complete study was included.

Exclusion criteria for the primary studies were 1) an overlap among articles or duplicate data; 2) the use of animals or cell lines; 3) insufficient data availability for estimating HR and 95 % CI, such as typical of abstracts, editorials, letters, conferences data, expert opinions, reviews, and case reports; 4) investigation of the relationship between Ki-67 and NSCLC using methods other than IHC; 5) inclusion of patients who underwent chemotherapy or radiotherapy interventions; and 6) a study sample comprising fewer than 20 patients.

Data extraction and literature quality assessment

Two investigators (SW and WZ) conducted the data extractions independently [10]. Any discrepancies were determined by reviewing the articles together until a consensus was reached. The following information was extracted from each article: name of first author and publication date; study population characteristics such as number of patients, age, gender, and treatment during follow-up; tumor data such as pathology, type of NSCLC, Ki-67 expression in the primary site, and TNM stage; variables such as tissue Ki-67 measurement method, cut-off value for the Ki-67 level; survival data, such as OS and DFS; and relevant quality scores. The primary data were the HR and 95 % CI for survival outcomes, including OS and DFS.

For study quality control, we used the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) and extracted 18 items (Additional file 3: Table S1). Each item was scored on a scale of 0–2, with 2 indicating a complete description, 1 indicating a partly matched description, and 0 indicating no matched description. The maximum score was 36 [11, 12]. Any discrepancies were resolved by a consensus discussion with a third reviewer (CL).

Statistical analysis

ORs with 95 % CIs were used to estimate the association between Ki-67 expression and the clinical characteristics of NSCLC patients, including age, gender, smoking habits, pathological type, TNM stage, tumor stage, lymph nodes status, and tumor differentiation status. According to the clinical characteristics, stages III and IV together were defined as ‘advanced stage’ and stages I and II as ‘early stage’. T2, T3, and T4 were all defined as ‘advanced stage’ compared with T1. N1, N2, and N3, which were combined into one group. Moderately and poorly differentiated were also combined [13, 14].

To identify the prognostic effect of Ki-67 expression, the overall HR and 95 % CI were evaluated for elevated Ki-67 expression. The combined ORs and HRs were initially estimated graphically using forest plots. Subgroup analyses were then conducted when the risk (OR or HR) was significant (P < 0.05).

The heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and the Higgins I2 statistic. When the I2 was below 50 %, the studies were considered to have acceptable heterogeneity, and a fixed effects model was used; otherwise, a random effect model was used.

To assess the stability of the results, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which one study at a time was removed to examine its individual influence on the pooled HR. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot with Egger’s and Begg’s tests. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant publication bias. Additionally, ‘trim and fill’ analyses were used to evaluate the stability of our meta-analysis results if the plots were asymmetric [15]. All analyses were performed using the STATA software (er. 12.0; Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

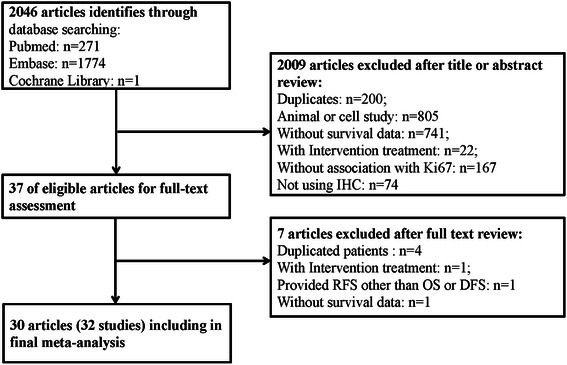

We identified 2046 potentially relevant articles through the search strategy described in Methods. As shown in Fig. 1, 2009 articles were excluded after the first screening based on the abstracts and/or titles, and 37 articles remained after reviewing their full texts for relevance. Seven articles were ultimately excluded, due to overlap with previously reported studies (n = 4) [16–19], use of interventional treatments (n = 1) [20], a lack of survival data (n = 1) [21], or providing RFS other than OS/DFS in NSCLC (n = 1) [22]. Additionally, two of the articles could be divided into two studies [23, 24]. Thus, a total of 30 eligible articles [5–9, 23–47] involving 32 studies were included in this meta-analysis. The flow diagram of the study selection procedure is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the relevant studies selection procedure

As demonstrated in Table 1, 5600 patients with related clinical data from a total of 6178 patients were enrolled in the 32 studies, which were published between 1993 and 2014. All 32 studies were retrospective. Of the 32 studies, 11 were conducted in Japan, five in America, four in China, four in Italy, two in Canada, two in Korea, and one each in Argentina, Brazil, the Czech Republic, and Germany. The case size of each study varied from 44 to 494 (median, 156) patients. The age of the patients ranged from 19 to 89, and the overall proportion of males was 66.11 %.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the final meta-analysis of Ki-67 expression and prognosis of NSCLC

| First-Author and Year | Country | Total Patients, H/L | Mean age | Gender (M/F) | History | TNM Stage | Antibody and dilution | Cut-off (%) | Followup (median Month) | Survival Analysis, year | HR estimated | OS/DFS HR (95%CI) | Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn 2014 | Korea | 109,20/89 | 65 | 65/44 | NSCLC | I-III | Anti-Ki67; 1:50 | 40 | 30 | OS/DFS,5 | S.urves | O:1.60(0.74-3.44) D:2.875(1.326-6.234) | 34 |

| Cagini 2000x | Italy | 99,43/56 | 66 | 91/8 | NSCLC | I-II | MIB-1; 1:100 | 20 | 41 | OS, 5 | Events | O:1.33(0.72-2.43) | 31 |

| D’amico 1999 | USA | 408,204/204 | 62.9 | 269/139 | NSCLC | I | MIB-1, NA | 7 | 60 | OS,5 | Events | O:1.41(0.99-2.00) | 33 |

| Demarchi 2000 | Brazil | 64,32/32 | 59.8 | 43/21 | ADC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:400 | 22.2 | 51.9 | OS,5 | R | O:0.49(0.20-1.22) | 31 |

| Fontanini 1996 | Italy | 65,31/34 | 46 | 63/7 | NSCLC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:200 | 30.2 | 45 | OS,3 | R | O:1.05(0.83-1.324) | 34 |

| Haga 2003 | Japan | 187,112/75 | NA | 120/67 | ADC,SCC | I | MIB-1; 1:100 | 10 | 120 | OS,5 | Events | O:3.636(1.267-10.439) | 33 |

| Harpole 1996 | USA | 275,109/106 | 63 | 177/98 | NSCLC | I | Anti-Ki67; NA | 7 | 68 | OS, 5 | Events | O:1.53(1.00-2.37) | 34 |

| Hayashi 2001 | Japan | 98,36/62 | 62.7 | 56/42 | ADC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:200 | 12.6 | 60 | OS,5 | R | O:2.0(1.1-3.8) | 29 |

| Hommura 2000 | Japan | 215,116/99 | 63.3 | 144/71 | NSCLC | I-IV | MIB-1; 1:50 | 30 | 84 | OS,3 | R | O:2.53(1.35-4.72) | 34 |

| Huang 2005 | Japan | 173,117/56 | 67 | 116/57 | NSCLC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:40 | 25 | 77 | OS,5 | Events | O:1.56(0.99-2.44) | 32 |

| Ishida 1997 | Japan | 114,57/57 | 64.9 | 59/55 | ADC | I-II | MIB-1; 1:50 | 22.7 | 28.5 | OS,5 | S.urves | O:8.50(3.52-20.53) | 32 |

| Kaira 2008 | Japan | 361,186/135 | 67 | 196/125 | NSCLC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:40 | 25 | 48 | OS,5 | R | O:0.667(0.271-1.643) | 32 |

| Liu 2012a | China | 494,113/381 | 61 | 366/128 | ADC,SCC | I-IV | Anti-Ki67; 1:200 | 50 | 25.9 | OS,5 | R | O:1.583(1.100-2.277) | 32 |

| Liu 2012b | China | 174,88/79 | 60 | 133/41 | ADC,SCC | I-IV | Anti-Ki67; 1:200 | 50 | 25 | OS,5 | R | O:1.681(0.487-5.797) | 32 |

| Maddau 2006 | Italy | 180,103/77 | 65.5, | 151/29 | NSCLC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:50 | 25 | 3-47 | OS,3 | R | O:0.79(0.55-1.15) | 29 |

| Mehdi 1998 | USA | 243,154/49 | 63.5 | 184/76 | NSCLC | I-II | MIB-1; 1:150 | 25 | 60 | OS/DFS,3 | S.urves | O:1.60(1.06-2.41) D:1.58(1.06-2.41) | 36 |

| Minami 2002 | Japan | 47,22/25 | 64 | 28/19 | ADC | I | MIB-1; NA | 20 | 89 | OS,5 | R | O:1.022(0.96-1.08) | 33 |

| Navaratnam 2012a | Canada | 79,37/42 | 69.2 | 47/32 | NSCLC | I-II | MIB-1; 1:50 | 20 | 36 | OS,3 | R | O: 1.81(0.93-3.53) | 30 |

| Navaratnam 2012b | Cadana | 58,20/38 | 62.8 | 23/35 | NSCLC | I-II | MIB-1; 1:50 | 10 | 36 | OS,3 | R | O:1.31(0.68-2.52) | 24 |

| Nguyen 2000 | Czech | 89,34/55 | 60 | 73/16 | NSCLC | I-IV | MIB-1; NA | 30 | 36 | OS,3 | S.urves | O:2.15(1.21-3.78) | 28 |

| Pence 1993 | USA | 61,15/46 | 63 | 56/5 | NSCLC | I-IV | Anti-Ki67; 1:100 | PI 3.5 | 38 | OS,5 | S. urves | O:2.18(1.00-4.78) | 29 |

| Poleri 2003 | Argentina | 50,28/22 | 60.8 | NA | ADC,SCC | I | MIB-1; NA | 33 | 59 | DFS,5 | Events | D:4.10(1.98-8.46) | 33 |

| Puglisi 2002 | Italy | 81,28/53 | 62.5 | NA | ADC,SCC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:100 | 34.2 | 115.76 | OS,5 | R | O: 1.29(0.71-2.31) | 33 |

| Ramnath 2001 | USA | 212,118/94 | 63.7 | 111/101 | NSCLC | I-IV | MIB-1; 1:100 | 25 | 24.3 | OS,3 | S. Curve | O:1.41(0.93-2.12) | 31 |

| Shiba 2000 | Japan | 156,81/75 | 62.4 | 112/44 | NSCLC | I-III | MIB-1; 1:100 | 20 | 49 | OS,5 | S. Curve | O:2.20(1.38-3.53) | 34 |

| Takahashi 2002 | Japan | 62,22/40 | 66.9 | 40/22 | ADC,SCC | I-II | MIB-1; 1:100 | 25 | 3.9 | DFS,5 | R | D:1.02(0.32-3.30) | 33 |

| Warth 2014 | Germany | 482,230/252 | 63.2 | NA | ADC | I-IV | MIB-1, 1:500 | 25 | 45.6 | OS/DFS,5 | S. Curve | O:1.86(1.29-2.69) D:1.29(1.02-1.64) | 29 |

| Woo 2009 | Japan | 184,79/105 | 67.8 | 92/92 | NSCLC | I | MIB-1; NA | 10 | 35.9 | DFS,5 | R | D:3.84(1.18-12.45) | 34 |

| Wu 2013 | China | 192,120/72 | 59 | 104/88 | NSCLC | I-III | Anti-Ki67; 1:200 | 10 | 60 | OS/DFS,5 | R | O:2.829(1.26-4.525) D:2.929(2.184-4.928) | 32 |

| Yamashita 2011 | Japan | 44,13/31 | NA | 25/19 | NSCLC | I | Anti-Ki67; 1:100 | 5 | 60 | DFS,5 | R | D:12.5(1.1-140.7) | 33 |

| Yoo 2007 | Korea | 219,17/209 | 65.8 | 168/51 | ADC,SCC | I-III | Anti-Ki67; NA | 30 | 38.9 | OS,5 | R | O:0.827(0.319-2.140) | 36 |

| Zhong 2014 | China | 270,66/204 | 62 | 192/78 | ADC,SCC | I-III | Anti-Ki67; 1:200 | 50 | 60 | OS,5 | R | O:2.179(1.096-4.333) | 34 |

Abbreviation: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, NSCLC non-small-cell Lung cancer, ADC adenocarcinoma, SCC squamous carcinoma, R Author reported, O, OS, D,DFS, H High expression, L Low expression, S. curve Survival curve

All studies included information on disease stage, and the proportion of stages I + II was 67.9 %. IHC was the only technique used to detect Ki-67 expression, using various antibodies and cut-off values (range, 5–50 %), and 2503 (44.70 %) tissue samples had ‘high’ Ki-67 expression (Table 1).

Of the 32 studies, 19 provided HR and 95 % CI values directly, whereas in the other 13 studies, they were calculated from available data (n = 6) or from Kaplan–Meier survival curves (n = 7), as described by Tierney [48]. Of the 32 studies, 20 identified high Ki-67 expression as an indicator of poor prognosis, whereas the remaining 12 studies showed no significant effect of high Ki-67 expression on survival outcome.

Methodological quality of the studies

The results of the quality assessment of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Quality scores ranged from 24 to 36, with a median value of 33. All of the studies satisfied most of the items and reported totals for the assay methods and confounders.

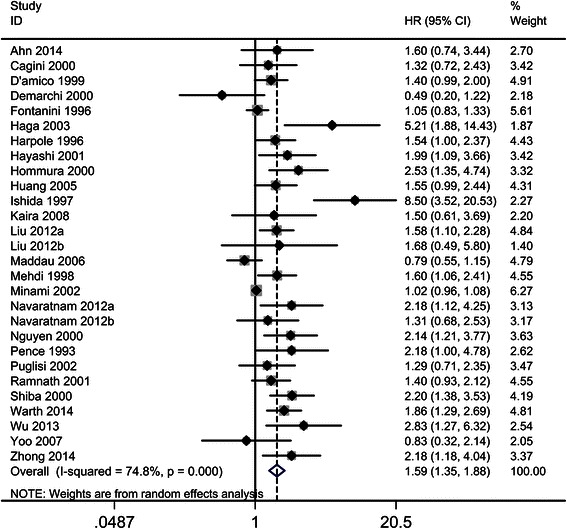

Correlation of high Ki-67 expression with OS in NSCLC

Of the 28 studies investigating the association between Ki-67 expression and OS, 14 involved Asian patients (n = 2729) and 14 involved non-Asian patients (n = 2287). The overall HR and 95 % CI for NSCLC patients was 1.59 (95 % CI 1.35–1.88, P < 0.001, n = 5007), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 74.8 %, P < 0.001; Fig. 2, Table 2). Subgroup analyses showed that the risk was significant in both Asian and non-Asian patients (HR 1.97, 95 % CI 1.43–2.71, P < 0.001 and HR 1.37, 95 % CI 1.15–1.64, P = 0.013, respectively) with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 82.1 %, P < 0.001 and I2 = 74.0 %, P < 0.001, respectively).

Fig. 2.

The hazard ratio (HR) of Ki-67 expression associated with OS in all NSCLC patients. HR > 1 implied worse OS for the group with high Ki-67 expression

Table 2.

HR values of OS and DFS of NSCLC subgroups

| Outcome | Studies (n) | Patients | HR | 95%CI | P value | Model | H, I2, P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | All study | 28 | 4534 | 1.58 | 1.33-1.87 | 0.000 | Random | 100.02,74.0 %,0.000 |

| Asian | 14 | 2729 | 1.97 | 1.43-2.71 | 0.000 | Random | 72.62,82.1 %,0.000 | |

| Non-Asian | 14 | 2278 | 1.37 | 1.15-1.64 | 0.013 | Random | 22.99,74.0 %,0.000 | |

| Stage I | 8 | 1144 | 1.85 | 1.27-2.69 | 0.001 | Random | 32.90,78.7 %,0.000 | |

| Stage I-II | 8 | 1166 | 1.72 | 1.20-2.46 | 0.003 | Random | 29.43,76.2 %,0.000 | |

| Stage I-III | 7 | 1038 | 1.60 | 1.21-2.12 | 0.001 | Fixed | 9.44, 36.5 %,0.150 | |

| Stage III-IV | 1 | 58 | 1.31 | 0.68-2.53 | 0.42 | Fixed | - | |

| ADC | 10 | 1327 | 2.21 | 1.38-3.50 | 0.000 | Random | 64.38,86.0 %,0.000 | |

| Asian | 6 | 666 | 3.01 | 1.96-4.02 | 0.000 | Random | 8.70,42.5 %,0.122 | |

| Non-Asian | 4 | 661 | 1.31 | 0.74-2.33 | 0.359 | Random | 18.38,83.7 %,0.000 | |

| Stage I-II | 6 | 446 | 3.30 | 1.37-7.96 | 0.008 | Random | 45.94,89.1 %,0.000 | |

| Stage I-III/IV | 4 | 881 | 1.51 | 0.92-2.47 | 0.102 | Random | 7.75,761.3 %,0.051 | |

| Non-ADC | 2 | 184 | 1.88 | 0.88-4.01 | 0.105 | Fixed | - | |

| DFS | All study | 8 | 1326 | 2.21 | 1.43-3.43 | 0.000 | Random | 28.35,75.3 %,0.000 |

| Asian | 5 | 591 | 2.78 | 1.78-4.34 | 0.000 | Random | 4.67,14.4 %,0.323 | |

| Non-Asian | 3 | 735 | 1.83 | 1.09-3.06 | 0.022 | Random | 48.95,77.7 %,0.01 | |

| Stage I | 3 | 293 | 4.31 | 2.37-7.84 | 0.000 | Fixed | 0.79,0.0 %,0.672 | |

| Stage I-II | 2 | 265 | 1.51 | 1.02-2.23 | 0.038 | Fixed | 0.48,0.0 %,0.486 | |

| Stage I-III/IV | 3 | 783 | 2.02 | 0.97-4.20 | 0.06 | Random | 11.69, 82.9 %, 0.0.06 |

Abbreviation: ADC adenocarcinoma, CI confidence interval, DFS disease-free survival, Fixed, Fixed, Inverse Variance model, H Heterogeneity, HR hazard ratio, I2 I-squared, OS overall survival, Random, Random, I-V heterogeneity model

Next, subgroups including TNM stage (eight studies for stage I, eight for stages I–II, seven for stages I–III, and one for stages III–IV) and type of NSCLC (10 studies for ADC and two for non–ADC) were analyzed. The analyses indicated that high Ki–67 expression was associated with a shorter OS in stage I, stages I–II, and stages I–III patients (HR 1.85, 95 % CI 1.27–2.69, P = 0.001; HR 1.72, 95 % CI 1.20–2.46, P = 0.003; and HR 1.60, 95 % CI 1.21–2.12, P = 0.001, respectively) with heterogeneity (I2 = 78.7 %, P < 0.001; I2 = 76.1 %, P < 0.001; and I2 = 36.5 %, P = 0.001, respectively), but no association with shorter OS was observed in patients in stages III–IV (HR 1.31, 95 % CI 0.68–2.53, P = 0.42).

Another subgroup analysis (ADC vs. non–ADC) demonstrated that the ADC group showed a significant association between high Ki–67 expression and shorter OS (HR 2.21, 95 % CI 1.38–3.50, P < 0.001). However, the association was not significant in the non-ADC group (HR 1.88, 95 % CI 0.88–4.01, P = 0.105). Additionally, only Asian patients (vs. non-Asian patients) and the early-stage group (stages I–II vs. advanced stage) in the ADC group demonstrated significant associations between high Ki–67 expression and shorter OS. The combined HRs were 3.01, 95 % CI 1.96–4.02, P < 0.001 and 3.30, 95 % CI 1.37–7.96, P = 0.008, respectively. Non-Asian ADC patients and ADC patients at advanced stages of the disease showed no significant association between high Ki–67 expression and OS (HR 1.88, 95 % CI 0.88–4.01, P = 0.359 and HR 1.51, 95 % CI 0.92–2.47, P = 0.102, respectively).

Correlation of high Ki-67 expression with OS in NSCLC using different cut-off values

Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the risks between Ki–67 expression and OS were not significant using different Ki-67 cut–off values (10 %, 25 %, 50 %). The pooled HRs and 95 % CIs were as follows: 1.80 (95 % CI 1.20–2.70) vs. 1.53 (95 % CI 1.28–1.84) for a cut–off value of 10 %, 1.57 (95 % CI 1.27–1.95) vs. 1.60 (95 % CI 1.22–2.08) for a cut–off value of 25 %, and 1.56 (95 % CI 1.30–1.86) vs. 1.72 (95 % CI 1.27–2.33) for a cut–off value of 50 % with significant heterogeneities (Additional file 4: Table S2, Additional file 5: Figure S1, Additional file 6: Figure S2 and Additional file 7: Figure S3).

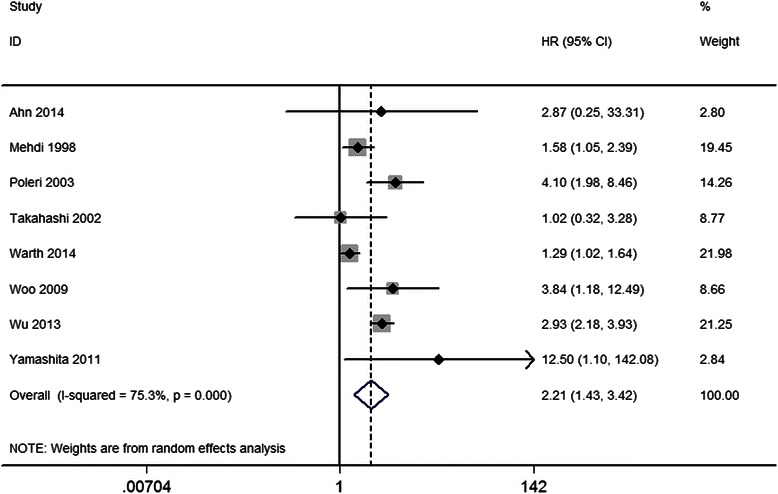

Correlation between high Ki-67 expression and DFS in NSCLC

The pooled HR and 95 % CI for DFS provided in eight studies was 2.21, 95 % CI 1.43–3.43, P < 0.001, with heterogeneity (I2 = 75.3 %, P < 0.001; Fig. 3, Table 2). Subgroup analysis showed that the risk in Asian patients was higher than that in non-Asian patients, and the combined HRs and 95 % CIs were as follows: HR 2.78, 95 % CI 1.78–4.34, P < 0.001 and HR 1.83, 95 % CI 1.09–3.06, P = 0.022, respectively. Further subgroup analysis indicated that the very early stage (stage I) showed the highest risk, when compared with stages I–II or I–III, with the following combined HRs and 95 % CIs: HR 4.31, 95 % CI 2.37–7.84, P < 0.001; HR 1.51, 95 % CI 1.02–2.23, P = 0.038; and HR 2.02, 95 % CI 0.97–4.20, P < 0.06, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The hazard ratio (HR) of Ki-67 expression associated with DFS in all NSCLC patients. HR > 1 implied worse OS for the group with high Ki-67 expression

Association between high Ki-67 expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of NSCLC

In this meta-analysis, clinicopathological features, such as age, gender, smoking habits, pathological type, lymph node status, and tumor differentiation grade, as impacted by increased Ki-67 expression were compared on the basis of the 32 studies. The results of the meta-analysis showed significant associations between high Ki-67 expression and being male, smoking habits, being a non-ADC patient, higher tumor stage (T2-4) and poorer differentiation grade (moderate or poor); the combined ORs and 95 % CIs were as follows: OR 1.89, 95 % CI 1.53–2.33, P < 0.001; OR 2.20, 95 % CI 1.72–2.82, P < 0.000; OR 1.88, 95 % CI 1.60–2.22, P < 0.001; OR 1.46, 95 % CI 1.13–1.88, P = 0.004; and OR 1.47, 95 % CI 1.15–1.88, P = 0.002, respectively. Moreover, significant associations between Ki–67 and gender (male), being a non-ADC patient, higher tumor stage, and poorer differentiation were seen only in Asian NSCLC patients. The combined ORs and 95 % CIs were as follows: OR 2.18, 95 % CI 1.67–2.81, P < 0.001; OR 2.22, 95 % CI 1.82–2.70; OR 1.47, 95 % CI 1.12–1.94, P = 0.006; and OR 1.50, 95 % CI 1.15–1.94, P = 0.002, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

OR values for NSCLC subgroups according to clinical characteristics

| Outcome of interest | Studies | Patients | OR | 95%CI | P value | Model | H, I2, P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (>60 vs. <60) | n = 6 | 1531 | 1.08 | 0.85-1.37 | 0.553 | Fixed | 5.37,6.9 %,0.37 |

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | n = 11 | 2696 | 1.89 | 1.53-2.33 | 0.000 | Fixed | 10.52,5.0 %,0.40 |

| Asian | n = 8 | 1933 | 2.18 | 1.67-2.81 | 0.000 | Fixed | 5.97,0.0 %,0.54 |

| Non-Asian | n = 3 | 763 | 1.38 | 0.96-1.99 | 0.084 | Fixed | 0.97,0.0 %,0.61 |

|

Smoke habits

(Smoke vs. Non-smoke) |

n = 7 | 1785 | 2.20 | 1.72-2.82 | 0.000 | Fixed | 4.77,0.0 %,0.57 |

| Non-ADC vs. ADC | n = 15 | 3185 | 1.88 | 1.60-2.22 | 0.000 | Fixed | 17.13,18.3 %,0.25 |

| Asian | n = 10 | 2345 | 2.22 | 1.82-2.70 | 0.000 | Fixed | 3.81,0.0 %,0.92 |

| Non-Asian | n = 5 | 840 | 1.31 | 0.98-1.75 | 0.073 | Fixed | 4.74,15.6 %,0.32 |

| T 2-4 vs T 1 | n = 9 | 2156 | 1.46 | 1.13-1.88 | 0.004 | Fixed | 3.13,0.0 %,0.93 |

| Asian | n = 7 | 1938 | 1.47 | 1.12-1.94 | 0.006 | Fixed | 2.86,0.0 %,0.83 |

| Non-Asian | n = 2 | 218 | 1.37 | 0.71-2.65 | 0.349 | Fixed | 0.23,0.0 %,0.63 |

| N 1-3 vs N 0 | n = 11 | 2443 | 1.01 | 0.83-1.22 | 0.927 | Fixed | 10.73,6.8 %,0.38 |

| Differentiation (well vs. moderate/poor) | n = 9 | 2029 | 1.47 | 1.15-1.88 | 0.002 | Fixed | 6.04,0.0 %,0.64 |

| Asian | n = 7 | 1837 | 1.50 | 1.15-1.94 | 0.002 | Fixed | 5.14,0.0 %,0.53 |

| Non-Asian | n = 2 | 192 | 1.28 | 0.60-2.74 | 0.517 | Fixed | 0.81,0.0 %,0.37 |

Abbreviation: ADC adenocarcinoma, CI confidence interval, Fixed, Fixed, Inverse Variance model, H Heterogeneity, I2 I-squared, OR,odds Ratio

There was no significant association between Ki–67 expression and age (>60 vs. < 60) or lymph node status (N1–3 vs. N0); the combined ORs and 95 % CIs were OR 1.08, 95 % CI 0.85–1.37, P = 0.553 and OR 1.01, 95 % CI 0.83–1.22, P = 0.927, respectively (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled HRs of OS and DFS were similar to those calculated after one study was removed and the rest were reanalyzed (Additional file 8: Figure S4 and Additional file 9: Figure S5). Moreover, the HR remained unchanged (HR 1.86, 95 % CI 1.44–2.28, P < 0.001 and HR 2.74, 95 % CI 1.25–4.22, P < 0.001, respectively) after the ‘trim and fill’ method was used (Additional file 10: Figure S6 and Additional file 11: Figure S7). Additionally, we report the combined HR and 95 % CI results of the fixed effects model: pooled HR 1.86, 95 % CI 1.44–2.28, P < 0.001 for OS and pooled HR 1.52, 95 % CI 1.08–1.96, P < 0.001 for DFS. These values were consistent with the random-effects model. Both analyses support the reliability of our results.

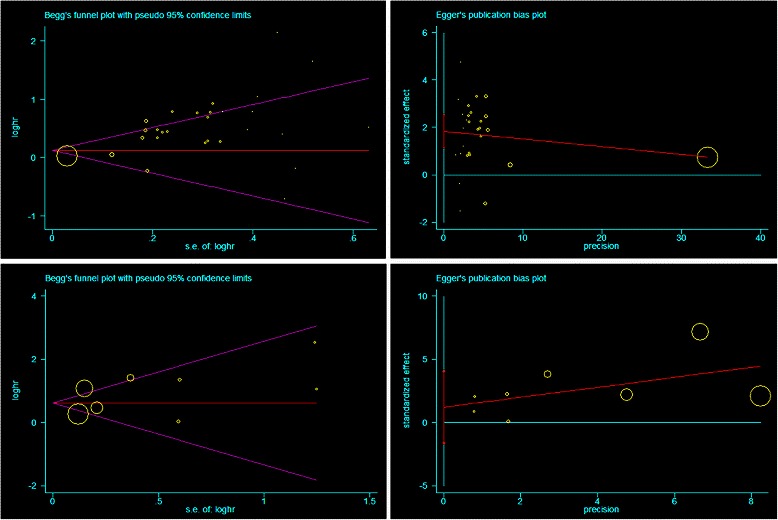

Publication bias

Begg’s test indicated no publication bias among the studies included in the current meta-analysis regarding the HRs of OS and DFS, with P values of 0.395 and 0.902, respectively. Egger’s test indicated no publication bias for DFS (P = 0.34), but it showed seemingly significant publication bias for OS after assessing the funnel plot (P < 0.001; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Funnel Plots of Begg’s and Egger’s were used to detect publication bias on OS and DFS. Begg’s funnel plots showed seemingly publication bias on OS (A) while Egger’s funnel plots showed no publication bias on OS in all NSCLC. It showed no publication bias on DFS in Begg’s test (C) and Egger’s test (D)

Discussion

Ki-67 is a nuclear non-histone protein first identified 30 years ago [2]. Because it is expressed during all phases of the cell cycle except the resting stage (G0), it has been used as a marker to evaluate proliferation in NSCLC [5, 9, 33, 44], as well as in other tumors, such as lymphoma [13], esophageal cancer [49], breast cancer [10], and prostate cancer [50]. Nonetheless, studies examining the relationship between Ki-67 expression and NSCLC prognosis have been inconsistent [33, 35, 42, 45].

Meta-analytic techniques using non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs) may be useful in certain clinical settings where the number or the sample size of the RCTs is insufficient [48]. The results of the current meta-analysis revealed that high Ki-67 expression in patients with NSCLC was associated with a poorer prognosis for OS (HR 1.59, 95 % CI 1.35–1.88, P < 0.001), consistent with a previous meta-analysis, published in 2004 [2], but in this case with nearly three–fold as many patients and double the number of studies. In addition, it was first reported that high Ki-67 expression in NSCLC patients was associated with a poor survival outcome for DFS (combined HR 2.21, 95 % CI 1.43–3.43, P < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis suggested that the association between high Ki-67 expression and NSCLC prognosis was stable and unchanged after removing any one study. Also, the results of the current meta-analysis show that high Ki-67 expression was more common in males (OR = 1.89, P < 0.001), smokers (OR = 2.20, P < 0.001), those in later tumor stages (OR = 1.46, P = 0.004), or those with poorer differentiation (OR = 1.47, P = 0.002), which has been linked to more aggressive tumors. Overall, the results of the current meta-analysis suggest that increased Ki-67 expression exerts a significantly adverse effect on the prognosis of NSCLC patients. To our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive and detailed meta-analysis to evaluate the association between Ki-67 expression and survival in NSCLC patients.

NSCLC is a malignancy displaying substantial heterogeneity, and the clinical and biological characteristics of the different subtypes of NSCLC vary substantially [51]. In this meta-analysis, high Ki-67 expression was a valuable indicator both of OS and DFS for ADC; this is consistent with the latest large-scale study conducted by Warth and colleagues, which included 1482 patients [47]. Furthermore, higher Ki-67 expression was a more valuable indicator for early (stages I–II) NSCLC and early (stages I–II) ADC. However, it showed no association between survival and being a non-ADC patient, with a HR of 1.88 and a 95 % CI of 0.88–4.01 for OS. Due to the strict inclusion criteria, only two studies in the current meta-analysis were included, and several studies without enough survival data were excluded. However, several types of non-ADC including squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC), large cell lung carcinoma (LCC), and bronchial gland carcinoma (BGC) may make it difficult to obtain reliable results. The association between high Ki-67 expression and survival outcome in non-ADC patients still requires further investigation.

It was reported that Asian ethnicity is a favorable prognostic factor for OS in NSCLC and is independent of smoking status [52, 53]. However, no data regarding the impact of Ki-67 and race/ethnicity on the outcome of NSCLC patients are available. Subgroup analysis in this study showed that higher Ki-67 expression indicated a poorer outcome in Asian NSCLC patients compared with non-Asian patients (HR 1.97, 95 % CI 1.43–2.71 vs. HR 1.37, 95 % CI 1.15–1.64 for OS and HR 2.78, 95 % CI 1.78–4.34 vs. HR 1.83, 95 % CI 1.09–3.06 for DFS). To date, there has been no consensus regarding the significance of Ki-67 in NSCLC in Asian versus non-Asian NSCLC patients. In the current study, a strong relationship was established between poor prognostic indicators and Ki-67 expression only in Asian patients. In addition, high Ki-67 expression was associated with larger tumor size and differentiation, which is in line with previous studies [2]. Furthermore, we found higher Ki-67 expression levels in Asian patients compared with non-Asian patients (31.39 % vs. 26.77 %, Additional file 12: Table S3), whereas no positive patients/total patients ratio differences were demonstrated (44.91 % vs. 47.18, P = 711). Therefore, the alteration of Ki-67 expression may contribute to the differences in the tumor biology observed between Asian and non-Asian patients with NSCLC. Although, future validation and investigations are needed, these data may provide new insights into biological aggressiveness of NSCLC in Asian versus in non-Asian patients.

Heterogeneity was significant in this meta-analysis, and it could not be ruled out by using a random-effects model or multiple subgroup analyses. For reasons of homogeneity, we analyzed only the studies dealing with NSCLC histology and restricted the analysis to the histological subtypes or tumor stages for which we had sufficient numbers of studies. Furthermore, the technique(s) used to identify the expression of Ki-67 can be a potential source of bias. The use of different antibodies (anti-Ki67 mAb or anti-MIB-1 mAb) and a protocol to count the number of cells stained by these antibodies without a received standard antibody concentration may yield variation among the studies. Moreover, the cut-off value used to define a tumor with ‘positive’ Ki-67 staining is often arbitrary and varies according to the investigator, from a low percentage to more than 50 %. Martin et al. [2] introduced two cut-off levels for defining Ki-67 expression in tumors, one to exclude patients with slowly proliferating tumors due to chemotherapeutic protocols (10 %) and one to identify patients sensitive to chemotherapy protocols (25 %). In addition, Warth et al. introduced 50 % as the cut-off value for defining Ki-67 expression in SQCC [47]. In this study, the adverse effect of high Ki-67 expression on OS showed similar results using these three recommended cut-off values (Additional file 4: Table S2, Additional file 5: Figure S1, Additional file 6: Figure S2 and Additional file 7: Figure S3). Nonetheless, a consensus for the optimal cut-off value for Ki-67 needs to be reached and validated in NSCLC patients in future studies.

It is important to note that the current study encountered difficulties, similar as most meta-analysis. First, it was based on summary data rather than data from individual patients. Therefore, multivariate analyses for confounding factors such as histological subtypes, gender and smoking status were not performed. A meta-regression model that adjusted for those factors that were found to be correlated with high K-67 levels was also not performed, too. Second, our search was limited to published studies and excluded unpublished trials or results in abstract form, which may have led to publication bias. Third, the unequal number of studies from Asian countries, with data derived mainly from Japan, China, and Korea may have also been a source of bias. Hence, our analysis may reflect outcomes from East Asia rather than from Asia in general.

There are several advantages to this study. First, large numbers (32 studies and 5600 patients) were analyzed, whereas only 17 studies and 1863 NSCLC patients were considered in the meta-analysis published in 2004. Second, important clinical parameters including age, gender, tumor stage, histology, and race/ethnicity were included in the analysis. The association between high Ki-67 expression and DFS was also investigated. However, as several limitations still exist, the results need to be interpreted cautiously. First, the number of included studies and included NSCLC patients were relatively small. Moreover, heterogeneity was inevitable among the groups due to the impossibility of matching patient characteristics across all studies. This may have weakened the results to some extent. Second, publication bias was unavoidable for clinical evidence, because the relevant data were extracted from non-randomized controlled trials. Third, reports in languages other than English were excluded; therefore, potential language bias may have been present. Lastly, some data for OS were extracted from survival curves or other available data rather than provided directly. Although the method used for extrapolation of HRs and 95 % CIs is widely accepted and we did not identify any major differences in current study (Additional file 13: Figure S8), we could not completely eliminate inaccuracy in the extracted survival rates.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our systematic review of the literature showed that high expression of Ki-67 in NSCLC patients, particularly during the early stages (stages I–II), in Asians, and in ADC patients is a poor prognostic indicator for survival outcome. Further adequately designed prospective studies with standardization of the immunohistochemistry technique, especially standardization of the cut-off threshold value, need to be conducted to confirm these results.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (#81401460, #91029720 and #81260238), Cultivation of High-level Innovation Health Talents of ZheJiang (#2012-241), grant from Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (#20151522070010, #20151122070030), grant from health and family planning of Jiangxi Province (#20155294) and Natural Science Foundation of Second Affiliated Hospital, Nanchang University (#2014YNQN12015).

Abbreviations

- LC

Lung cancer

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ADC

Adenocarcinoma

- BGC

Bronchial gland carcinoma

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- OS

Overall survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

Additional files

PRISMA 2009 checklist in current meta-analysis.

Based on the editor's work. PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram in current meta-analysis.

Definitions of 18 items of study reporting quality.

HR values of OS of NSCLC subgroups depended on cutoff value.

The hazard ratio (HR) of Ki-67 expression associated with overall survival (OS) in all NSCLC patients subgroup (cutoff value >10 % and cutoff value <10 %).

The hazard ratio (HR) of Ki-67 expression associated with overall survival (OS) in all NSCLC patients subgroup (cutoff value >25 % and cutoff value <25 %).

The hazard ratio (HR) of Ki-67 expression associated with overall survival (OS) in all NSCLC patients subgroup (cutoff value >50 % and cutoff value <50 %).

Sensitivity analysis of all the studies assessing OS.

Sensitivity analysis of all the studies assessing DFS.

Trim and fill analysis of all the studies assessing OS.

Trim and fill analysis of all the studies assessing DFS.

Comparisons of Ki-67 expression in NSCLC between Asian and Non-Asian Studies.

The hazard ratio (HR) of Ki-67 expression associated with OS in all NSCLC patients subgroup (NA: HR and 95%CI extracted from articles; R: HR and 95%CI provided directly).

Footnotes

Song Wen, Wei Zhou and Chun-ming Li contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The authors’ contributions are as follows: SW and PC were responsible for the concept and design of the study. SW and WZ searched the databases according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. CL,JH and XH helped extract quantitative data from papers. SW and WH analyzed the data. SW and GS wrote the manuscript. PC and WH reviewed and edited the manuscript extensively. All of the authors were involved in interpretation of results and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Song Wen, Email: songwen81@163.com.

Wei Zhou, Email: zhouw11a@sina.com.

Chun-ming Li, Email: 422784401@qq.com.

Juan Hu, Email: 283205287@qq.com.

Xiao-ming Hu, Email: xiaominghuefy@163.com.

Ping Chen, Email: wenscp2014@126.com.

Guo-liang Shao, Phone: +86057188122515, Email: shaoguoliang666@hotmail.com.

Wu-hua Guo, Phone: +86079186301760, Email: guowuhuadoctor@126.com.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin B, Paesmans M, Mascaux C, Berghmans T, Lothaire P, Meert AP, et al. Ki-67 expression and patients survival in lung cancer: Systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:2018–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakobsen JN, Sorensen JB. Clinical impact of ki-67 labeling index in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;79:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugsley JM, Schmidt RA, Vesselle H. The Ki-67 index and survival in non-small cell lung cancer: a review and relevance to positron emission tomography. Cancer J. 2002;8:222–33. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn HK, Jung M, Ha SY, Lee JI, Park I, Kim YS, et al. Clinical significance of Ki-67 and p53 expression in curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014;35:5735–40. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1760-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo T, Okudela K, Yazawa T, Wada N, Ogawa N, Ishiwa N, et al. Prognostic value of KRAS mutations and Ki-67 expression in stage I lung adenocarcinomas. Lung Cancer. 2009;65:355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haga Y, Hiroshima K, Iyoda A, Shibuya K, Shimamura F, Iizasa T, et al. Ki-67 expression and prognosis for smokers with resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1727–32. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00119-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Liu D, Masuya D, Nakashima T, Kameyama K, Ishikawa S, et al. Clinical application of biological markers for treatments of resectable non-small-cell lung cancers. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1231–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, et al. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression in resectable stage I-III nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:742–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(264–269):w264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen M, Cai E, Huang J, Yu P, Li K. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1126–34. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang YJ, Qi WX, He AN, Sun YJ, Shen Z, Yao Y, et al. Prognostic value of tissue vascular endothelial growth factor expression in bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:645–9. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.2.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Chen Z, Fu T, Jin X, Yu T, Liang Y, et al. Ki-67 is a valuable prognostic predictor of lymphoma but its utility varies in lymphoma subtypes: evidence from a systematic meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chen M, Huang J, Zhu Z, Zhang J, Li K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of tumor biomarkers in predicting prognosis in esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:539. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Zhao J, Ma R, Lin H, Liang X, Cai X, et al. Prognostic significance of E-cadherin expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e103952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Amico TA, Aloia TA, Moore MB, Herndon JE 2nd, Brooks KR, Lau CL, et al. Molecular biologic substaging of stage I lung cancer according to gender and histology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:882–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Harpole DH, Jr, Herndon JE, 2nd, Wolfe WG, Iglehart JD, Marks JR. A prognostic model of recurrence and death in stage I non-small cell lung cancer utilizing presentation, histopathology, and oncoprotein expression. Cancer Res. 1995;55:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, et al. CD98 expression is associated with poor prognosis in resected non-small-cell lung cancer with lymph node metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3473–81. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong X, Guan X, Liu W, Zhang L. Aberrant expression of NEK2 and its clinical significance in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Letters. 2014;8:1470–6. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van de Vaart PJ, Belderbos J, de Jong D, Sneeuw KC, Majoor D, Bartelink H, et al. DNA-adduct levels as a predictor of outcome for NSCLC patients receiving daily cisplatin and radiotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:160–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000320)89:2<160::AID-IJC10>3.3.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn HK, Jung M, Ha SY, Lee JI, Park I, Kim YS, et al. Clinical significance of KI67 expression in curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:S1216–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182746772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SJ, Rabbani ZN, Dewhirst MW, Vujaskovic Z, Vollmer RT, Schreiber EG, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7925–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu YZ, Jiang YY, Hao JJ, Lu SS, Zhang TT, Shang L, et al. Prognostic significance of MCM7 expression in the bronchial brushings of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Lung Cancer. 2012;77:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navaratnam S, Skliris G, Qing G, Banerji S, Badiani K, Tu D, et al. Differential role of estrogen receptor beta in early versus metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Hormones and Cancer. 2012;3:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s12672-012-0105-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cagini L, Monacelli M, Giustozzi G, Moggi L, Bellezza G, Sidoni A, et al. Biological prognostic factors for early stage completely resected non- small cell lung cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:53–60. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200005)74:1<53::AID-JSO13>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Amico TA1, Massey M, Herndon JE 2nd, Moore MB, Harpole DH Jr. A biologic risk model for stage I lung cancer: Immunohistochemical analysis of 408 patients with the use of ten molecular markers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:736–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Demarchi LM, Reis MM, Palomino SA, Farhat C, Takagaki TY, Beyruti R, et al. Prognostic values of stromal proportion and PCNA, Ki-67, and p53 proteins in patients with resected adenocarcinoma of the lung. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:511–20. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fontanini G, Vignati S, Bigini D, Mussi A, Lucchi M, Chiné S, et al. Recurrence and death in non-small cell lung carcinomas: a prognostic model using pathological parameters, microvessel count, and gene protein products. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1067–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harpole DH, Jr, Richards WG, Herndon JE, 2nd, Sugarbaker DJ. Angiogenesis and molecular biologic substaging in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1470–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi H, Ogawa N, Ishiwa N, Yazawa T, Inayama Y, Ito T, et al. High cyclin E and low p27/Kip1 expressions are potentially poor prognostic factors in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Lung Cancer. 2001;34:59–65. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hommura F, Dosaka-Akita H, Mishina T, Nishi M, Kojima T, Hiroumi H, et al. Prognostic significance of p27(KIP1) protein and Ki-67 growth fraction in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4073–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishida H, Irie K, Itoh T, Furukawa T, Tokunaga O. The prognostic significance of p53 and bcl-2 expression in lung adenocarcinoma and its correlation with Ki-67 growth fraction. Cancer. 1997;80:1034–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970915)80:6<1034::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maddau C, Confortini M, Bisanzi S, Janni A, Montinaro F, Paci E, et al. Prognostic significance of p53 and Ki-67 antigen expression in surgically treated non-small cell lung cancer: Immunocytochemical detection with imprint cytology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:425–31. doi: 10.1309/DQ2AGXV2P8QT0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehdi SA, Etzell JE, Newman NB, Weidner N, Kohman LJ, Graziano SL, et al. Prognostic significance of Ki-67 immunostaining and symptoms in resected stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 1998;20:99–108. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(98)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minami K, Saito Y, Imamura H, Okamura A. Prognostic significance of p53, Ki-67, VEGF and Glut-1 in resected stage I adenocarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2002;38:51–7. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(02)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen VN, Mirejovsky P, Mirejovsky T, Melinova L, Mandys V. Expression of cyclin D1, Ki-67 and PCNA in non-small cell lung cancer: prognostic significance and comparison with p53 and bcl-2. Acta Histochem. 2000;102:323–38. doi: 10.1078/S0065-1281(04)70039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pence JC, Kerns BJM, Dodge RK, Iglehart JD. Prognostic significance of the proliferation index in surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1382–90. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420240090017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poleri C, Morero JL, Nieva B, Vázquez MF, Rodríguez C, de Titto E, et al. Risk of recurrence in patients with surgically resected stage I non-small cell lung carcinoma: Histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Chest. 2003;123:1858–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Puglisi F, Minisini AM, Aprile G, Barbone F, Cataldi P, Artico D, et al. Balance between cell division and cell death as predictor of survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncology. 2002;63:76–83. doi: 10.1159/000065724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramnath N, Hernandez FJ, Tan DF, Huberman JA, Natarajan N, Beck AF, et al. MCM2 is an independent predictor of survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4259–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiba M, Kohno H, Kakizawa K, Iizasa T, Otsuji M, Saitoh Y, et al. Ki-67 immunostaining and other prognostic factors including tobacco smoking in patients with resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1457–65. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1457::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi S, Kamata Y, Tamo W, Koyanagi M, Hatanaka R, Yamada Y, et al. Relationship between postoperative recurrence and expression of cyclin E, p27, and Ki-67 in non-small cell lung cancer without lymph node metastases. Int J Clin Oncol. 2002;7:349–55. doi: 10.1007/s101470200053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J, Zhou J, Yao L, Lang Y, Liang Y, Chen L, et al. High expression of M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor is a novel biomarker of poor prognostic in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Tumor Biol. 2013;34:3939–44. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0982-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamashita S, Moroga T, Tokuishi K, Miyawaki M, Chujo M, Yamamoto S, et al. Ki-67 labeling index is associated with recurrence after segmentectomy under video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:341–6. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.10.01573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoo J, Jung JH, Lee MA, Seo KJ, Shim BY, Kim SH, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of non-small cell lung cancer: Correlation with clinical parameters and prognosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:318–25. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.2.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong X, Guan X, Dong Q, Yang S, Liu W, Zhang L, et al. Examining Nek2 as a better proliferation marker in non-small cell lung cancer prognosis. Tumor Biol. 2014;35:7155–62. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warth A, Cortis J, Soltermann A, Meister M, Budczies J, Stenzinger A, et al. Tumour cell proliferation (Ki-67) in non-small cell lung cancer: a critical reappraisal of its prognostic role. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1222–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tierney JFSL, Ghersi D. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh R, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, K Sharma R, D Mittal R. Impact of CYP3A5 and CYP3A4 gene polymorphisms on dose requirement of calcineurin inhibitors, cyclosporine and tacrolimus, in renal allograft recipients of North India. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;380:169–77. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollack A, DeSilvio M, Khor LY, Li R, Al-Saleem TI, Hammond ME, et al. Ki-67 staining is a strong predictor of distant metastasis and mortality for men with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy plus androgen deprivation: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 92-02. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2133–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moldvay J. Personalized therapy in non-small cell lung cancer: from diagnosis to therapy. Orv Hetil. 2012;153:909–16. doi: 10.1556/OH.2012.29397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ou SH, Ziogas A, Zell JA. Asian ethnicity is a favorable prognostic factor for overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and is independent of smoking status. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1083–93. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181b27b15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang SJ, Fuller CD, Thomas CR., Jr Ethnic disparities in conditional survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:180–90. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318031cd4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]