Abstract

Objectives:

Current evidence supports the use of various second-generation antipsychotics for pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. While in a systematic review, generally no difference in efficacy was found between atypical antipsychotics, other studies have found quetiapine less effective than aripiprazole. This article reviews the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole versus quetiapine in the context of recommended management strategies for schizophrenia.

Method:

Fifty female inpatients, meeting the diagnosis of schizophrenia, were randomly entered into two groups (n = 25 in each group) to participate in a 12-week, double-blind study for random assignment to quetiapine or aripiprazole. The primary outcome measures were Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms. The schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI), Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale (CGI-S) and the Simpson Angus Scale (SAS) were also used as secondary measures.

Results:

Both quetiapine and aripiprazole showed significant effectiveness in the improvement of positive symptoms. The effectiveness for negative symptoms was also noteworthy with both drugs, although not to a significant level during this study. In addition, significant improvement was found on assessment with CGI-S and SAI for quetiapine and aripiprazole. SAS did not show any important increment in extrapyramidal side effects at the end of the examination.

Conclusion:

According to the findings, quetiapine and aripiprazole had similar effectiveness and tolerability with respect to management of schizophrenia.

Keywords: aripiprazole, quetiapine, schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia is commonly considered a neurodevelopmental disorder that is associated with significant morbidity; however, unlike other neurodevelopmental disorders, the symptoms of schizophrenia often do not manifest for decades. In most patients, the formal onset of schizophrenia is preceded by prodromal symptoms, including positive symptoms, mood symptoms, cognitive symptoms and social withdrawal. The proximal events that trigger the formal onset of schizophrenia are not clear but may include developmental biological events and environmental interactions or stressors. Treatment with antipsychotic drugs clearly ameliorates psychotic symptoms and maintenance therapy may prevent the occurrence of relapse. The use of atypical antipsychotic agents may additionally ameliorate the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and prevent disease progression. Moreover, if treated properly early in the course of illness, many patients can experience a significant remission of their symptoms and are capable of a high level of recovery following the initial episode [Lieberman et al. 2001]. During the past decade, there has been some progress in the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Current evidence supports the use of various second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotic medications, although few of these agents have been associated with long-term efficacy and tolerability [Stip and Tourjman, 2010]. Quetiapine, an antagonist of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2 (5-HT2) and 5-HT6, D1 and D2, H, and α1 and α2 receptors, is an atypical antipsychotic with, theoretically, a low propensity for movement disorder adverse effects. It is used for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychoses, while it is not much different from first-generation antipsychotics and risperidone with respect to treatment withdrawal and efficacy. In comparison to first-generation antipsychotics and risperidone, quetiapine has a lower risk of movement disorders but higher risks of dizziness, dry mouth and sleepiness. High dropout rates in short quetiapine studies are a major problem and make interpreting any results problematic [Srisurapanont et al. 2004]. Aripiprazole is a quinolinone derivative with a high affinity for dopamine D2 and D3 receptors, and serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors. The mechanism of action of aripiprazole is not yet known, but evidence suggests that its efficacy in the treatment of the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia and its lower propensity for extrapyramidal symptoms may be attributable to aripiprazole’s partial agonist activity at dopamine D2 receptors. Also aripiprazole may improve cognitive function and has a low propensity to cause clinically significant bodyweight gain, hyperprolactinaemia or corrected QT interval prolongation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. In addition, there were no clinically relevant differences in mean changes from baseline in measures of diabetes and dyslipidaemia between the aripiprazole and placebo groups in a 26-week, placebo-controlled trial [Swainston Harrison and Perry, 2004]. Based on the clinical evidence, including data from short-term (4–8 weeks) and long-term (26–52 weeks) randomized, double-blind clinical trials, aripiprazole has been associated with improvements in positive, negative, cognitive and affective symptoms of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. It has been associated with long-term (up to 52 weeks) symptom control in schizophrenia, as well as with efficacy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia [Taylor, 2003]. While in a systematic review, generally no difference in efficacy has been found between atypical antipsychotics [Citrome, 2012], other studies have found that quetiapine is less effective than aripiprazole [Crespo-Facorro et al. 2013]. Essentially aripiprazole is considered the best available option for long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [Azekawa et al. 2011], especially with respect to existing problems relating to global state of energy, mood, negative symptoms,somnolence and weight gain [Khanna et al. 2013]. This article reviews the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole versus quetiapine in the context of recommended management strategies for schizophrenia.

Method

This study was approved by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences’s (USWR) Medical Ethics Committee. An accessible sample of 50 female inpatients in the chronic ward of the hospital were given a full explanation of the procedure and provided signed informed consent. The patients underwent a minimum washout period of 10–14 days and were randomly assigned into one of two groups, receiving either aripiprazole or quetiapine. Patients were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) [APA, 2013]. The appraisal was performed through a double-blind, 12-week trial, while the patients, staff and assessor were unaware of the prescribed drugs that were packed into identical capsules. Aripiprazole was initiated at a dose of 5–10 mg/day and then increased by 5 mg increments at weekly meetings to a maximum of 25 mg by week 4 and then this dose was held constant until the end of the study. Quetiapine was started at 25–50 mg twice daily or three times daily, and then increased by 150 mg at weekly meetings to a maximum of 600 mg by week 4 and this dose was held constant until the end of the study. No other psychotropic drug or psychosocial intervention was administrated during the trial. The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [Andreasen, 1984] and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [Andreasen, 1981] were used as the primary outcome measures. The Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale (CGI-S) [Guy, 1976], Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI) [David, 1990] and finally the Simpson Angus Scale (SAS) [Simpson and Angus, 1970] were also employed as secondary scales. The study duration was 12 weeks and the patients were assessed by means of SAPS and SANS at baseline (week 0), and at weeks 4, 8 and 12. The other scales were scored at baseline and at the end of the assessment.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients were compared by means of t tests. Treatment efficacy was also analyzed by t test and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing both groups over 12 weeks. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p value less than or equal to 0.05. Cohen’s standard (d) and correlation measures of effect size (r) were used for comparing baseline with endpoint changes in primary outcome measures. MedCalc, version 9.4.1.0, was used as the statistical software tool for analysis.

Results

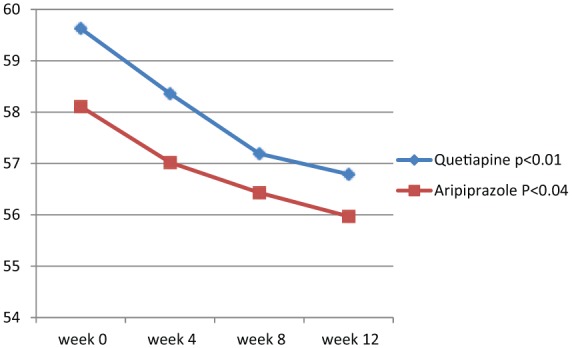

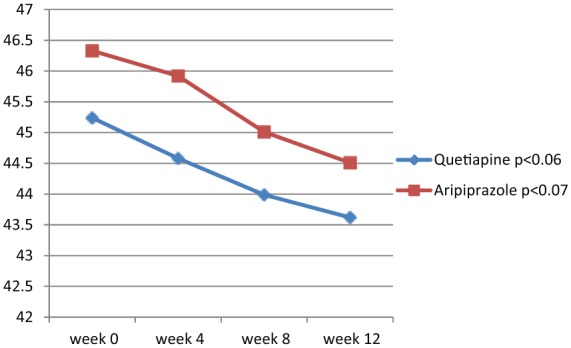

Analysis of efficacy was based on data from an equal number of patients in the quetiapine and aripiprazole groups. Groups were initially comparable and demographic and diagnostic variables were analogous (Table 1). According to the findings of this study, both quetiapine and aripiprazole showed significant effectiveness in the improvement of positive symptoms (p < 0.01 and p < 0.04 respectively) (Figure 1). The effectiveness in treating negative symptoms was also noteworthy with both drugs, although not to a significant level during this study (p < 0.06 and p < 0.07, respectively) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Repeated measures ANOVA for SAPS showed significant improvements with quetiapine and aripiprazole at the end of the trial [F(3, 72) = 2.09, p < 0.03, SS (Sum of Squares) = 19.79, MSe (Mean Squares) = 3.26; and F(3, 72) = 2.13, p < 0.05, SS = 20.82, MSe = 3.29 respectively]. However, split-plot (mixed) design ANOVA did not show any significant difference in efficiency between quetiapine and aripiprazole with respect to positive symptoms [F(3, 96) = 0.408, p < 0.71, SS = 10.87, MSe = 12.38]. Also, repeated measures ANOVA for SANS did not show any significant improvement in the quetiapine group [F(3, 72) = 0.241, p < 0.84, SS = 3.19, MSe = 4.47] or the aripiprazole group [F(3, 72) = 0.254, p < 0.69, SS = 3.27, MSe = 4.31]. In addition to a head to head t test, split-plot (mixed) design ANOVA did not show any significant difference with respect to SANS between the groups at week 12 [F(3, 96) = 0.349, p < 0.99, SS = 11.51, MSe = 12.43] (Table 3). Furthermore, CGI-S score was significantly improved in both groups (p < 0.05 for each group) (Table 2). In addition, SAI showed significant progress with quetiapine (p < 0.04) and aripiprazole (p < 0.05) during the assessment. According to the findings, SAS did not show any significant increment in extrapyramidal side effects at the end of the examination (p < 0.69 and p < 0.06 respectively). As the sample size was somewhat small, the effect size was analyzed at the end of treatment for changes in SAPS and SANS. Regarding SAPS, the results indicated a medium range of improvement with quetiapine (d and r = 0.6 and 0.3) and aripiprazole (d and r = 0.5 and 0.2), and the same range of enhancement for SANS (d and r = 0.5 and 0.2 respectively). Post - hoc power analysis showed a power equal to 0.53 on behalf of this trial(intermediary), which turned to power = 0.81, in compromise power analysis. The mean modal dose of quetiapine and aripiprazole during the present assessment was 463.04 ± 101.37 mg/day and 20.4 ± 3.51mg/day respectively. The most common adverse effects of quetiapine and aripiprazole in our samples during the trial were somnolence (n = 8 and n = 3 respectively), dizziness (n = 4 and n = 1 respectively), weight gain (n = 4 in the quetiapine group, with a mean increase of 0.23 ± 0.07 kg), inner unrest (n = 6 in the aripiprazole group) and mild stiffness (n = 2 in the aripiprazole group, which resolved with 2–3 mg/day trihexyphenidyl). Since the side effects were mild and well tolerated, no one dropped out owing to medication intolerance.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the patients participating in the quetiapine and aripiprazole groups.

| Variable | Quetiapine (N = 25) | Aripiprazole (N = 25) | t | p value | Df | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age, y | 35.23+/−6.89 | 38.44+/−4.91 | 1.283 | 0.20 | 48 | −3.98, 0.88 |

| duration of illness, y | 6.83+/−1.63 | 6.39+/−1.58 | 0.969 | 0.33 | 48 | -0.47, 1.35 |

| Baseline SAPS | 59.63+/−4.48 | 58.11+/−3.92 | 1.277 | 0.20 | 48 | −0.87, 3.91 |

| Baseline SANS | 45.24+/−3.17 | 46.33+/−3.61 | −1.134 | 0.26 | 48 | −3.02, 0.84 |

| Baseline SAI | 3.27+/−0.61 | 3.25+/−0.81 | 0.099 | 0.92 | 48 | −0.39, 0.43 |

| Baseline SAS | 0.34+/−0.06 | 0.32+/−0.13 | 0.698 | 0.48 | 48 | −0.04, 0.08 |

| Baseline CGI-S | 3.79+/−1.07 | 3.69+/−0.97 | 0.346 | 0.73 | 48 | −0.48, 0.68 |

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale; CI, confidence interval; SAI, Schedule for Assessment of Insight; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SAS, Simpson Angus Scale.

Figure 1.

Changes in Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms between baseline (week 0) and week 12.

Table 2.

Intra-group analysis of different outcome measures between baseline and 12th week.

| Measure | Quetiapine baseline | Quetiapine 12th week | t | p | 95% CI | Aripiprazole baseline | Aripiprazole 12th week | t | p value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAPS | 59.63 ± 4.48 | 56.79 ± 3.74 | 2.433 | 0.01 | 0.49, 5.19 | 58.11 ± 3.92 | 55.97 ± 3.23 | 2.107 | 0.04 | 0.10, 4.18 |

| SANS | 45.24 ± 3.17 | 43.62 ± 2.79 | 1.918 | 0.06 | −0.08, 3.32 | 46.33 ± 3.61 | 44.51 ± 3.49 | 1.812 | 0.07 | −0.20, 3.84 |

| CGI-S | 3.79 ± 1.07 | 3.20 ± 1.01 | 2.005 | 0.05 | −0.00, 1.18 | 3.69 ± 0.97 | 3.14 ± 1.03 | 1.944 | 0.05 | −0.02, 1.12 |

| SAI | 3.27 ± 0.61 | 3.01 ± 0.11 | 2.097 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.51 | 3.25 ± 0.81 | 2.90 ± 0.39 | 2.002 | 0.05 | −0.00, 0.72 |

| SAS | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | −0.399 | 0.69 | −0.06, 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.13 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | −1.897 | 0.06 | −0.12, 0.00 |

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale; CI, confidence interval; SAI, Schedule for Assessment of Insight; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SAS, Simpson Angus Scale.

Figure 2.

Changes in Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms between baseline (week 0) and week 12.

Table 3.

Between-group analysis of different outcome measures at 4th, 8th and 12th week.

| Measures | Quetiapine N = 25 | Aripiprazole N = 25 | t | p value | Df | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAPS 4th week | 58.36 ± 4.84 | 57.02 ± 3.71 | 1.099 | 0.27 | 48 | −1.11, 3.79 |

| SAPS 8th week | 57.19 ± 3.65 | 56.43 ± 3.28 | 0.774 | 0.44 | 48 | −1.21, 2.73 |

| SAPS 12th week | 56.79 ± 3.74 | 55.97 ± 3.23 | 0.830 | 0.41 | 48 | −1.17, 2.81 |

| SANS 4th week | 44.58 ± 2.96 | 45.92 ± 3.53 | −1.454 | 0.15 | 48 | −3.19, 0.51 |

| SANS 8th week | 43.99 ± 3.38 | 45.01 ± 4.03 | −0.970 | 0.33 | 48 | −3.14, 1.10 |

| SANS 12th week | 43.62 ± 2.79 | 44.51 ± 3.49 | −0.996 | 0.32 | 48 | −2.69, 0.91 |

| SAI 12th week | 3.01 ± 0.11 | 2.90 ± 0.39 | 1.357 | 0.18 | 48 | −0.05, 0.27 |

| SAS 12th week | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | −1.055 | 0.29 | 48 | −0.09, 0.03 |

| CGI-S 12th week | 3.20 ± 1.01 | 3.14 ± 1.03 | 0.208 | 0.83 | 48 | −0.52, 0.64 |

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale; CI, confidence interval; SAI, Schedule for Assessment of Insight; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SAS, Simpson Angus Scale.

Discussion

Historically, schizophrenia has been regarded with therapeutic pessimism. However, demonstration of good treatment outcomes in patients with first-episode and recent-onset schizophrenia and the association between episodes and duration of active psychosis, and progression and outcome of the disorder have resulted in efforts and hope that morbidity may be limited and the course of illness altered by early intervention [Lieberman et al. 2001]. The advent of atypical antipsychotic drugs may be a consequential factor in this evolving therapeutic strategy because their improved safety and efficacy profile compared with standard neuroleptics has increased the likelihood that patients will adhere to treatment and potentially experience improved therapeutic effects. In addition, preliminary evidence suggests that atypical antipsychotics may have undefined properties that will more efficiently ameliorate the pathophysiology of schizophrenia associated with psychosis and thereby prevent disease progression. However, some authors have suggested that pharmacologic treatment suppresses the symptoms of schizophrenia but does not alter the course or potential progression of the disease [Hegarty et al. 1994]. In contrast, others have postulated that antipsychotic drugs ameliorate the pathophysiologic process that causes psychotic symptoms and leads to clinical deterioration [Jody et al. 1990; Lieberman et al. 1997; Wyatt, 1991]. In many countries of the industrialized world second-generation (‘atypical’) antipsychotics have become the first-line drug treatment for people with schizophrenia. The question as to whether, and if so how much, the effects of the various second-generation antipsychotics differ is a matter of debate. According to a general survey, olanzapine may be a more efficacious drug than some other second-generation antipsychotic drugs like amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone or ziprasidone. This is because olanzapine improved the general mental state (Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) total score) more than aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone, but not more than amisulpride or clozapine. This better efficacy was confirmed by fewer participants in the olanzapine groups leaving the studies early due to inefficacy of treatment compared with quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone .Fewer participants in the olanzapine group than in the quetiapine and ziprasidone treatment groups, but not in the clozapine group, had to be rehospitalized in the trials. This small superiority in efficacy needs to be weighed against an increased weight gain and associated metabolic problems compared with most other second-generation antipsychotic drugs, except clozapine [Komossa et al. 2010]. The objective of the present study was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole versus quetiapine in the context of recommended management strategies for schizophrenia. In this regard, the results showed that both drugs were similarly effective in significant reduction of severity of positive symptoms, nonsignificant improvement in negative symptoms, and particularly no significant augmentation of extrapyramidal side effects. Perhaps, a longer trial duration might result in significant improvement of negative symptoms in one or both groups. To date, these findings are in some ways compatible with the findings of Citrome who, with the exception of clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone, did not find any differences in efficacy between the other atypical antipsychotics in his meta-analyses [Citrome, 2012]. However, in another study, Crespo-Facorro and colleagues found that treatment with quetiapine was associated with a higher risk of treatment discontinuation owing to insufficient efficacy in comparison to aripiprazole and ziprasidone, and also a higher rate of responders with aripiprazole [Crespo-Facorro et al. 2013]. This finding was not well matched with our results. Also their finding that quetiapine was associated with a greater improvement in depressive symptoms maybe was not discernible at this point due to nonsignificant enhancement of negative symptoms. However, their statement that patients on quetiapine were less likely to be prescribed concomitant medications was also evident in our results. Khanna and colleagues in a comparison between aripiprazole and other Second Generation Antipsychotics (SGAs) did not find any important difference between aripiprazole and olanzapine with respect to global mental state and extrapyramidal symptoms, although they found fewer increases in cholesterol levels and weight gain for aripiprazole. This finding could also be valid in comparing aripiprazole with risperidone and ziprasidone when considering the global mental state of the treated patients [Khanna et al. 2013]. But, yet again, their finding regarding the advantageous effect of aripiprazole on mood and negative symptoms was not notably visible in our assessment. In addition, their remark that significantly more people given aripiprazole reported symptoms of nausea was not evident in our study. Finally, Azekawa and colleagues stated that aripiprazole may be considered the best available option for long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [Azekawa et al. 2011]. This needs to be considered with discretion based on the present results, which illustrated an increased trend for extrapyramidal side effects with aripiprazole in comparison to quetiapine. However, there is also strong evidence for a relationship between cognitive impairment and functional impairment in individuals with schizophrenia. Impaired cognition is common and alterations in cognition are present during development and precede the emergence of psychosis, taking the form of stable cognitive impairments during adulthood. Cognitive impairments may persist when other symptoms are in remission and contribute to the disability of the disease [APA, 2013]. Therefore, independent evaluation of the effect of different models of therapy on cognitive abilities of patients, in addition to positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia, is a necessary part of assessment, which could not be done in the present study. Small sample size, short duration of study, sex-based sampling and lack of a placebo arm, which may have a significant impact on the assay sensitivity of the study, were among the other weak points of this trial. Further large pragmatic randomized, well designed, long-term trials are necessary to compare the relative effects of different second-generation antipsychotic drugs.

Conclusion

According to the findings, quetiapine and aripiprazole had similar effectiveness and tolerability with respect to management of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges dear colleagues, S. Akbari, MD and P. Sadeghi, MS, and the Department of Research for their practical and financial support of this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Saeed Shoja Shafti, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Razi Psychiatric Hospital, PO Box 18735-569, Tehran, Iran.

Hamid Kaviani, University of Azad, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Andreasen N. (1981) The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, IA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. (1984) The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). [Google Scholar]

- APA (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Azekawa T., Ohashi S., Itami A. (2011) Comparative study of treatment continuation using second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 7: 691–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L. (2012) A systematic review of meta-analyses of the efficacy of oral atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia. Exp Opin Pharmacother 13: 1545–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B., Pérez-Iglesias R., Mata I., Ortiz-Garcia de la Foz V., Martínez Garcia O., Valdizan E., et al. (2013):Aripiprazole, ziprasidone, and quetiapine in the treatment of first-episode nonaffective psychosis: results of a 6-week, randomized, flexible-dose, open-label comparison. J Clin Psychopharmacol 33: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A. (1990) Insight and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 156: 798–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy R. (ed.) (1976) ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. DHEW Publication No. (ADM) 76–338. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty J., Baldessarini R., Tohen M., Waternaux C., Oepen G. (1994) One hundred years of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the outcome literature. Am J Psychiatry 151: 1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jody D., Lieberman J., Geisler S., Szymanski S., Alvir J. (1990) Behavioral response to methylphenidate and treatment outcome in first episode schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull 26: 297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna P., Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., Hunger H., Schwarz S., El-Sayeh H., et al. (2013) Aripiprazole versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD006569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., Hunger H., Schmid F., Schwarz S., Duggan L., et al. (2010). Olanzapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD006654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J., Perkins D., Belger A., Chakos M., Jarskog F., Boteva K., et al. (2001) The early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Biol Psychiatr 50: 884–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J., Sheitman B., Kinon B. (1997) Neurochemical sensitization in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: deficits and dysfunction in neuronal regulation and plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology 17: 205–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G., Angus J. (1970) A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 212(Suppl. 44): 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisurapanont M., Maneeton B., Maneeton N. (2004) Quetiapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stip E., Tourjman V. (2010) Aripiprazole in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a review. Clin Ther 32(Suppl. 1): 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swainston Harrison T., Perry C. (2004) Aripiprazole: a review of its use in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Drugs 64: 1715–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. (2003) Aripiprazole: a review of its pharmacology and clinical utility. Int J Clin Pract 57: 49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt R. (1991) Early intervention with neuroleptics may decrease the long-term morbidity of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 5: 201–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]