Abstract

Availability of energy functions which can discriminate native-like from non-native protein conformations is crucial for theoretical protein structure prediction and refinement of low-resolution protein models. This article reports the results of benchmark tests for scoring functions based on two all-atom ECEPP force fields, that is, ECEPP/3 and ECEPP05, and two implicit solvent models for a large set of protein decoys. The following three scoring functions are considered: (i) ECEPP05 plus a solvent-accessible surface area model with the parameters optimized with a set of protein decoys (ECEPP05/SA); (ii) ECEPP/3 plus the solvent-accessible surface area model of Ooi et al. (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:3086–3090) (ECEPP3/OONS); and (iii) ECEPP05 plus an implicit solvent model based on a solution of the Poisson equation with an optimized Fast Adaptive Multigrid Boundary Element (FAMBEpH) method (ECEPP05/FAMBEpH). Short Monte Carlo-with-Minimization (MCM) simulations, following local energy minimization, are used as a scoring method with ECEPP05/SA and ECEPP3/OONS potentials, whereas energy calculation is used with ECEPP05/FAMBEpH. The performance of each scoring function is evaluated by examining its ability to distinguish between native-like and non-native protein structures. The results of the tests show that the new ECEPP05/SA scoring function represents a significant improvement over the earlier ECEPP3/OONS version of the force field. Thus, it is able to rank native-like structures with Cα root-mean-square-deviations below 3.5 Å as lowest-energy conformations for 76% and within the top 10 for 87% of the proteins tested, compared with 69 and 80%, respectively, for ECEPP3/OONS. The use of the FAMBEpH solvation model, which provides a more accurate description of the protein-solvent interactions, improves the discriminative ability of the scoring function to 89%. All failed tests in which the native-like structures cannot be discriminated as those with low energy, are due to omission of protein–protein interactions. The results of this study represent a benchmark in force-field development, and may be useful for evaluation of the performance of different force fields.

Keywords: physics-based potentials, protein decoys, Poisson-Boltzmann continuum solvent model, surface area, molecular mechanics, refinement

INTRODUCTION

The availability of accurate all-atom energy functions is very important for reliable modeling of the properties of biological macromolecules. Although the large size of conformational space and the complexity of the energy landscape make extensive sampling and global energy optimization using all-atom force fields prohibitive for most biomolecular systems, all-atom potentials represent a very important tool for scoring and refining protein models produced by heuristic methods, such as Rosetta,1,2 TASSER,3,4 3D–SHOTGUN,5 and so forth. These methods were shown2 to produce sets of models which contain relatively accurate native-like conformations but they are usually not able to identify these native-like conformations reliably among a set of other models.

Because protein structure prediction is usually based on the Anfinsen thermodynamic hypothesis,6 a necessary requirement for energy functions to produce accurate protein-structure models is that they must recognize the native state of the protein as the conformation or a set of very similar conformations for which the system, that is, the protein plus its surroundings, is of lowest free energy. Therefore, scoring of large sets of protein models to discriminate native or near-native conformations from non-native structures is the first test which is carried out for any new potential.

The functions used for scoring protein conformations can be divided roughly into three categories: empirical,7 knowledge-based,8–10 and physics-based.11–13 Physics-based functions were shown to be a very promising tool for simulating, scoring, and refinement of protein models. They also have an advantage of being designed to model physical interactions and, therefore, are expected to have better transferability. Significant effort has been made in recent years to develop and evaluate new, more accurate, physics-based all-atom potentials. Several popular physics-based all-atom force fields, such as CHARMM,14 OPLS,15 and AMBER,16,17 combined with different implicit solvent models have been studied in detail for their ability to discriminate between the native or near-native structures and decoys. Thus, Lazaridis and Karplus18 used the CHARMM potential combined with a Gaussian model for the solvation free energy to select the native structures of several proteins from misfolded conformations. They found that the effective energy function, including a solvent term, is more successful than the vacuum potential when applied to structures relaxed by molecular dynamics (MD). Parameters of the CHARMM/EEF1 force field were optimized later19 using protein decoys that led to improved discriminative ability of the force field as was demonstrated using several popular decoy sets. The CHARMM19 force field was also used20 in conjunction with a generalized Born solvent model. The scoring function was able to identify the misfolded structures with over 90% accuracy when several sets of misfolded structures were considered. Scoring results for the function based on the newer version of the CHARMM force field, that is CHARMM22, combined with a GB/SA implicit solvation were reported recently.21

Results of extensive decoy detection tests using an effective free-energy function based on the OPLS all-atom force field, the surface GB model and local energy minimization were reported.22 Native structures had the best score for almost 90% of proteins considered.

A very popular AMBER force field16,17 has been used for scoring protein decoys in combination with different solvent models and scoring methods from energy evaluation to relatively long (2 ns) MD runs. Thus, Lee and Duan23 considered a scoring function including the AMBER force field in conjunction with short MD simulations and a GB solvent model. The scoring function was evaluated using seven different decoy sets and was able to discriminate native structures for 80–100% of proteins depending on the set. The AMBER potential combined with a more accurate Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) implicit solvent model was shown24 to consistently discriminate native crystal structures for 62 proteins from several widely used all-atom decoy sets after considering the heteroatom groups, disulfide bonds, and crystal packing effects. These results motivated Lee et al.25 to carry out a systematic comparison of the performance of the AMBER/GB and AMBER/PBSA force fields in discriminating native protein structures. It was found that the results obtained using the AMBER/PBSA potential were comparable with those of the GB-based scoring function.

Somewhat different scoring results were reported for the AMBER/GB energy function by Wroblewska and Skolnick26 who found that MD relaxation of the decoy structures led to significant deterioration of discriminative ability of the force field. Thus, the lowest energy structures were obtained from the native trajectories for 70% of the proteins when short MD runs were applied, whereas longer relaxation decreased this value to 20%. As a part of their subsequent work,27 the same authors compared two scoring functions based on the AMBER ff99 and ff03 parameter sets and showed that neither of them was successful in discriminating native-like conformations (the success rate was 20 and 48%, respectively). They also used the AMBER ff03 force field as a starting point for parameter refinement. As a result, the optimized AMBER-based force field with an explicit hydrogen-bond term was able to discriminate native structures as the lowest-energy ones for 90% of proteins.

A very advanced scoring function was considered by Vorobjev et al.28,29 It included free-energy evaluation using the CEDAR force field,30 a Poisson-Boltzmann-based FAMBE solvent model and an entropy term calculated over a short MD trajectory. Native structures of all the proteins considered were correctly found to be more stable than misfolded structures of the same sequence. On the other hand, prediction based on the total energy from MD simulations with explicit water succeeded only part of the time.

Finally, Verma and Wenzel12 applied PFF01, a force field similar to the one used in this work, to rank and cluster decoys for 32 proteins generated by ROSETTA.31 Each decoy was relaxed in a single simulated annealing run. Using the top 10 scoring conformations as a criterion, the authors found that PFF01 succeeded in selecting near-native conformations with an average Cα rmsd of 3.12 Å in 78% of the cases. This good discriminative ability of the scoring function was achieved by using a very simple surface area solvation model.

The ability to detect near-native protein structures from a set of decoys is directly related to the quality of the structures in the set. As was discussed by Tsai et al.,31 an optimal set of decoys should contain conformations for a large number of proteins with different architecture. It should also include a sufficient number of conformations close to the native structure (<4 Å) as well as conformations with a variety of tertiary (and possibly secondary) structures. And last but not least, it should consist of conformations that are near local minima of a reasonable scoring function. Several decoy sets are available and have been used for force-field evaluation. One of those sets, that is, Rosetta set,31 satisfies the criteria listed earlier. The latest, improved version of this decoy set32 was considered in this work.

Scoring results also depend strongly on the method used to compute the score for a given conformation. Many scoring methods include only energy evaluation or local energy minimization. Because of the ruggedness of the all-atom energy surface, small changes in atomic coordinates may lead to dramatic increases in energy. If a decoy set was generated using a very different force field (especially by using a coarse-grained representation and without sufficient refinement with a reasonable all-atom potential), energy evaluation or energy minimization may not provide an adequate description of the energy landscape. Moreover, the native structure will be favored because of its high stereochemical quality compared with that of other decoys. This accounts for the 90–100% accuracy in discriminating protein decoys reported for some scoring functions.19,20,22,24,27,33 Similar discriminative ability (80–100%) was reported23 when short (5 ps) MD runs were used as a scoring method. On the other hand, significant deterioration of the performance (<50%) of scoring functions was observed26,27 when energy minimizations were substituted by longer (up to 2 ns) MD runs. This result is understandable because, when decoy conformations are well relaxed with a given scoring function, unfavorable contacts present in decoys disappear and it becomes a real challenge to select the native or native-like structure from a set of competing decoys.

Despite the significant increase in accuracy of the available all-atom force fields and treatment of solvation effects, the physics-based scoring functions still exhibit difficulty in distinguishing native or native-like structures from non-native decoys when structure relaxation methods are used to compute the score. Therefore, the design of scoring functions which show close to 100% discrimination between native-like conformations and decoys, when combined with structure relaxation methods, remains a very important problem.

A new (ECEPP05) physics-based all-atom force field was reported recently.34 It is based on the ECEPP algorithm35 and is designed specifically for torsional angle representation which involves use of a rigid covalent-geometry approximation and, therefore, reduces the conformational space. The advantage of this representation is not only the smaller (~10 fold) dimensionality of the sampling space and faster energy evaluation at each step, but also in the more reliable local minimization, which has a much larger radius of convergence than Cartesian space local minimizations. This advantage is critical for many applications such as the docking of flexible ligands or conformational modeling of macromolecules.

In recent work,37 we introduced a new method of decoy-based force-field optimization which is aimed at stabilizing native-like conformations against a large set of decoys by creating free-energy gaps between the sets of native-like and non-native structures. The new method was applied to optimize the torsional and solvation parameters of the effective energy function built by using the ECEPP05 force field34 coupled with the OONS38 implicit surface-area solvation free-energy term. The resulting force field (ECEPP05/SA) was validated with an independent set of six nonhomologous proteins and seemed to be transferable to proteins not included in the optimization. Additionally, we examined the set of mis-folded structures created by Park and Levitt with a four-state reduced model.39 The results from these additional calculations confirmed the good discriminative ability of the optimized force field and indicated that the ECEPP05/SA force field represents a promising tool for protein simulations.

So far the ECEPP05/SA force field has been evaluated by using a relatively small decoy set. It should be mentioned that the decoy generation method used in the previous work37 experienced some difficulty in producing near-native conformations as well as decoys with very diverse secondary and tertiary structure. Therefore, we decided to test the ECEPP05/SA force field on one of the high-quality decoy sets available, which is generated by ROSETTA.32 This decoy set was developed specifically for force-field assessment and, therefore, would help us to obtain an unbiased evaluation of the force field. We also use short Monte Carlo-with-Minimization40,41 (MCM) runs to obtain a realistic picture of the energy landscape by relaxing unfavorable contacts and exploring the vicinity of each conformation for lower energy minima.

The goal of this investigation is twofold: first, to test the accuracy of the free-energy ECEPP05/SA force field on a high quality, independently generated decoy set and compare it with that of the earlier version of the ECEPP force field42 (ECEPP3/OONS). The SA solvation models, albeit computationally very efficient, are too simple to capture complex effects associated with the process of protein solvation. Therefore, our second goal is to evaluate the performance of the ECEPP05 force field combined with the recently developed, highly accurate FAM-PEpH solvation model43 based on the dielectric continuum approach and the Poisson-Boltzmann equation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forms of the potential function

The free energy is assumed to be a function of the torsional degrees of freedom (x), that is, all the backbone and side-chain torsional angles, of a protein (all bond angles and bond lengths being fixed at standard values42). Three alternative forms of the potential function are used to calculate the total free energy as a function of the coordinates x, viz.,

- The ECEPP/3 gas phase potential plus the OONS38 solvent accessible surface area model to treat the solvent (ECEPP3/OONS):

where Uint(x) is the internal conformational energy of the molecule in the absence of solvent, assumed to correspond to ECEPP/342 energy of a neutral molecule; and Gsas(x) represents the solvation free energy as defined by Ooi et al.38(1) -

The ECEPP05 gas phase potential plus the decoyoptimized solvent accessible surface area model to treat the effects of solvation (ECEPP05/SA):

This potential includes the same terms as in Eq. (1) but with Uint(x) assumed to correspond to the ECEPP0534 energy of a neutral molecule and Gsas(x) representing the solvation free energy with the parameters of the solvation model optimized using protein decoys.37

The main difference between the ECEPP/3 and ECEPP05 force fields (besides different parameterization) is in the functional form of the van der Waals energy (6–12 and 6-exp, respectively). The ECEPP/3 potential also contains an explicit 10–12 hydrogen-bonding term, whereas this interaction is represented implicitly in ECEPP05 by a combination of electrostatic and nonbonded interactions with the hydrogen involved in a hydrogen bond treated as a separate atom type with parameters different from those of the other types of hydrogens.

All ionizable residues and end groups were assumed to be neutral in calculations using the ECEPP3/OONS and ECEPP05/SA force fields.

- The ECEPP05 gas phase potential plus a multigrid boundary element method to treat the solvent (ECEPP05/FAMBEpH):

where Uint(x) is the intramolecular conformational potential energy of the protein computed in a gasphase approximation using ECEPP05, Gcav(x) is the free energy for creation of the molecular cavity in water, Gs, vdw(x) is the free energy of van der Waals interactions between the uncharged protein and the water solvent, is the free energy of polarization of the water solvent by the protein with gas phase partial charges on all atoms but with the ionizable groups in the neutral state, and the last term ΔGinz(x, pH) is the free energy of ionization of the protein at a given pH with respect to the gas phase as a reference state in which all ionizable groups are neutral. The sum of all the terms but the first one of Eq. (2) is equal to the total free energy of protein solvation for a given conformation x at fixed pH.(2)

A new optimized Fast Adaptive Multigrid Boundary Element (FAMBEpH) method to compute the and ΔGinz (x, pH) terms in Eq. (2) as a function of pH was published recently. The Poisson equation is solved with the FAMBEpH method with charges from the ECEPP05 force field34 and internal (εint) and solvent (εsolv) dielectric constants of 16 and 80, respectively. The value of εint = 16 is assumed as an adequate representation of the protein interior.43 FAMBEpH also includes the 1:1 salt effect indirectly. The values of 4.0, 4.4, 10.4, 9.6, 12.0, 6.6, and 8.3 were adopted as for the ionizable groups for residues Asp, Glu, Lys, Tyr, Arg, His, and Cys, respectively. The values of 7.80 and 3.75 for the α-amino and α-carboxyl groups46 were used for the of the ionizable N- and C-terminal groups, respectively.

Solvation free-energy calculations for each of the proteins considered in this work were carried out at pH 7.0 and salt concentration of 0.15M.

Scoring protocols

The performance of a given scoring function depends on how the score is computed. Scoring of protein decoys using physics-based functions is often carried out through energy evaluation. When the initial decoys are far from the energy minima of a given potential, such computations may not provide a realistic picture. This problem occurs for all-atom force fields because of the roughness of the underlying energy surface characterized by huge energy variations corresponding to small changes in structural parameters.

Local energy minimization is one way to relax unfavorable contacts. However, relatively dense packing of protein decoys makes energy minimization very inefficient at this task. A short conformational search, limited to the vicinity of the starting conformation, should enable one to overcome this problem and may provide information about the existence of lower energy minima corresponding to conformationally very similar structures. Therefore, in this work, we used two types of runs to evaluate the energies of protein decoys: (i) local energy minimizations and (ii) short MCM runs following the initial local energy minimizations. The effective free energy given by Eq. (1) with the parameters of either ECEPP05/SA or ECEPP3/OONS force field was used as a scoring function for both types of runs.

All local energy minimizations of the native structures of proteins from the protein data bank47 (PDB) and of the corresponding structures from the decoy sets considered in this work were carried out by using the SUMSL minimizer48 as implemented in the ECEPPAK program.49–51

Short MCM runs with constraints on the backbone ϕ and ψ torsional angles were carried out starting from each energy-minimized decoy by using the ECEPPAK program. The range of the angular variation was ±10°. The maximum number of accepted conformations was set to 50. All accepted conformations plus the starting decoy formed a set of structures which was analyzed in this work.

To compare the performance of different solvation models, that is, SA and FAMBEpH, combined with ECEPP05, we carried out a single energy evaluation for each decoy using the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH potential. Energy minimization with FAMBEpH is currently not feasible because of the unavailability of analytical expressions for the first derivatives of the solvation free energy.

Decoy set

The protein decoys considered in this work were taken from the test set of the Rosetta@home all-atom decoys.32

We selected 45 (listed in Table I) of 59 proteins constituting the original decoy set, that is those without any stabilizing ligands or disulfide bonds, because they cannot be accounted for by the present version of our force field. The selected proteins contain from 54 to 146 residues (Table I) and display a wide variety of secondary and tertiary structure.

Table 1.

The Cα Rmsd of the lowest energy decoys (Rmsdlow) after local energy minimization and MCM runs with the ECEPP05/SA force field

| Rmsdlow, Å |

Rmsdlow, Å |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | Nres | Rmsd, Å a | Minim. | MCM | PDB code | Nres | Rmsd, Å a | Minim. | MCM |

| α/β Proteins | |||||||||

| 1a19 | 90 | 0.6–24.3 | 0.90 | 1.08 | 1rnb | 109 | 0.8–26.5 | 1.70 | 2.06 |

| 1a68 | 87 | 0.6–20.3 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 1tig | 88 | 0.6–19.6 | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| 1acf | 125 | 0.6–22.5 | 3.14 | 3.66 | 1ubi | 71 | 0.5–16.4 | 0.72 | 0.83 |

| 1aiu | 105 | 0.9–22.0 | 1.61 | 1.61 | 1ugh | 82 | 0.7–22.1 | 0.87 | 1.55 |

| 1bm8 | 99 | 0.5–23.4 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 1vcc | 77 | 0.6–18.4 | 1.46 | 1.65 |

| 1ctf | 68 | 0.7–15.7 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 2chf | 128 | 0.5–22.2 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 1dhn | 121 | 0.6–30.9 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 1ew4 | 106 | 0.8–23.5 | 1.26 | 1.45 |

| 1iib | 103 | 0.7–18.5 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1hz6 | 61 | 0.6–15.6 | 3.81 | 3.66 |

| 1kpe | 108 | 0.8–21.4 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1scj | 66 | 0.7–16.2 | 7.70 | 7.73 |

| 1lou | 92 | 0.6–25.6 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 2ci2 | 62 | 0.5–17.7 | 11.25 | 9.60 |

| 1opd | 85 | 0.4–22.7 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 4ubp | 100 | 1.0–21.4 | 9.09 | 9.27 |

| 1pgx | 55 | 0.5–15.3 | 1.46 | 1.07 | 5cro | 55 | 0.5–16.2 | 10.0 | 8.34 |

| α Helical proteins | |||||||||

| 1a32 | 65 | 0.8–15.8 | 8.40 | 1.38 | 1eyv | 131 | 1.0–20.7 | 10.86 | 1.68 |

| 1ail | 70 | 0.8–21.8 | 5.00 | 3.77 | 1lis | 125 | 1.0–29.3 | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| 1bgf | 118 | 0.8–26.8 | 9.81 | 10.74 | 1r69 | 61 | 0.5–14.0 | 0.91 | 1.00 |

| 1bkr | 108 | 0.6–22.1 | 13.94 | 0.97 | 1cei | 85 | 0.6–21.0 | 0.89 | 1.08 |

| 1cg5 | 141 | 0.6–27.4 | 1.20 | 1.34 | 1utg | 70 | 0.9–5.1 | 4.64 | 4.63 |

| 1e6i | 110 | 0.8–22.1 | 1.34 | 1.34 | 1vls | 146 | 1.4–31.0 | 7.75 | 10.67 |

| 1enh | 54 | 0.5–14.3 | 2.11 | 2.74 | |||||

| β Proteins | |||||||||

| 1fna | 91 | 0.7–23.9 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1who | 94 | 0.7–26.0 | 1.05 | 0.95 |

| 1shf | 59 | 0.5–19.0 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1bk2 | 57 | 0.4–18.7 | 7.38 | 7.36 |

| 1ten | 89 | 0.5–25.7 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 1gvp | 87 | 1.2–25.7 | 15.06 | 15.04 |

| 1tul | 102 | 0.5–26.3 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1vie | 56 | 0.5–17.9 | 6.37 | 6.41 |

Rmsd range of the decoy set obtained as a result of the MCM runs starting from the energy-minimized Rosetta@home protein decoys.32

The decoy set for each protein includes: (a) the native structure (X-ray) from the PDB; (b) 20-relaxed native structures, that is the structures that have been put through refinement in Rosetta relieving clashes and, in some cases, repacking rotamers; (c) 100 lowest scoring models out of ~10,000 total models, produced by using the Rosetta de novo structure prediction algorithm and subjected to all-atom refinement. Thus, the total number of conformations available for each protein is 121. The structures of all the decoys were converted to ECEPP-type geometry, that is, with fixed (standard-value) bond lengths and bond angles.

A total of 121 structures per protein were energy minimized with both the ECEPP3/OONS and ECEPP05/SA force fields. The resulting conformations were used as starting structures for the MCM runs. Each MCM run carried out with either ECEPP3/OONS or ECEPP05/SA produced up to 50 new conformations which were added to the original set of decoys. As a result, the final decoy set produced for each protein included ~6000 conformations. Performance of a scoring function is usually evaluated by its ability to discriminate native-like conformations as the lowest or one of the 5–10 lowest-energy structures. Because of the ruggedness of the all-atom energy landscape and constraints used during the search, MCM runs yield clusters of similar conformations with comparable energies. To select 10 sufficiently different lowest-energy conformations, we applied the following clustering procedure. First, all the decoys obtained as a result of the MCM runs were divided into two subsets: (i) native-like decoys with RMSD ≤3 Å and (ii) the rest. Then, the decoys from the second subset were clustered by using the Minimal Spanning Tree method52 and assuming a specific rmsd cutoff of 3.0 Å for all heavy atoms and no cutoff in energy. For each protein, the size of the resulting ensemble [subset (i) plus any conformation remaining after clustering of subset (ii)] varied from ~700 to ~1600 conformations. The rmsd range of the final set for each protein is given in Table I.

Because a single energy evaluation using the FAM-BEpH solvation model is relatively time consuming, energy evaluations were carried out for the decoy sets obtained as the result of the clustering procedure.

All proteins were considered with unblocked neutral N- and C-termini.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The following subsections describe the results of the tests of the ECEPP05/SA, ECEPP3/OONS, and ECEPP05/ FAMBEpH scoring functions on the Rosetta@home decoy set. The main criteria used to assess performance of the scoring functions include: the Cα rmsd of the lowest scoring structure (excluding the native), from the native structure, and the best rmsd of the top 5 and top 10 scoring structures. Cα rmsd was chosen as a measure of similarity between different protein conformations to facilitate comparison with other works on this topic. It should be mentioned that the analysis carried out for ECEPP05/SA using all-heavy-atoms rmsd did not change any of conclusions obtained using Cα rmsd.

Performance of the ECEPP05/SA scoring function: energy minimization versus MCM search

The ability of the ECEPP05/SA force field to discriminate native-like from non-native conformations was assessed by starting from 121 decoys of each protein from Table I and carrying out local energy minimizations followed by short MCM runs.

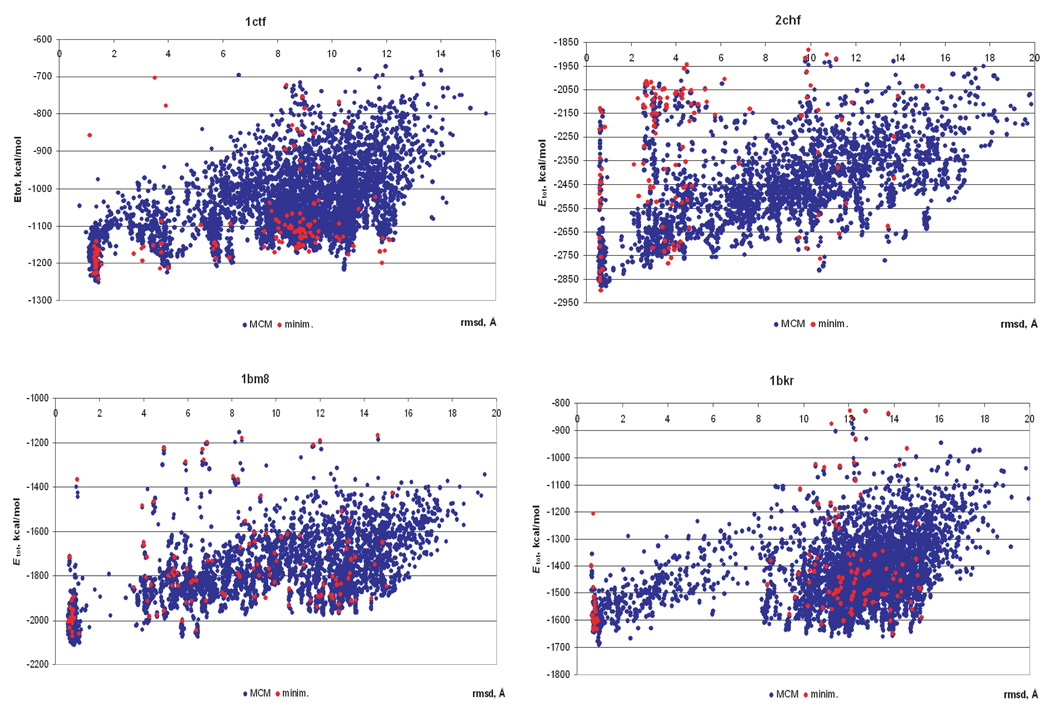

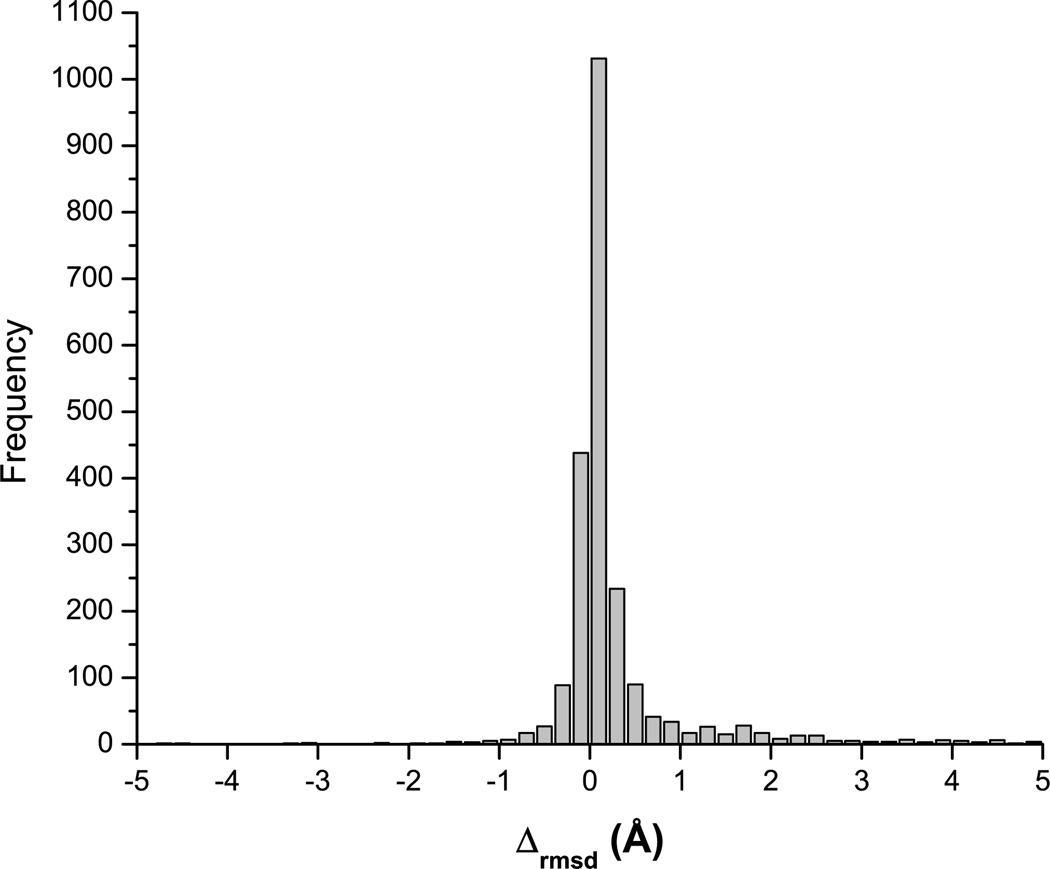

Figure 1 shows scatter-plots of the free energy of the decoys of 1ctf, 2chf, 1bm8, and 1bkr versus Cα rmsd from the native structure obtained as a result of local energy minimization followed by MCM runs. It can be seen that the MCM search systematically yields lower energy structures. It is interesting to note that the locally minimized energies of the initial 121 decoys (filled red circles in Fig. 1) are low for both native-like and non-native conformations indicating the high quality of the decoys and the lack of bias toward the native-like structures. The MCM search enabled us to explore the vicinity of each initial conformation as shown in Figure 2. The average change in Cα rmsd is ±0.4 Å. The increase in Cα rmsd is slightly more frequent (positive values of Δrmsd in Fig. 2) which indicates that the MCM search with torsional constraints used in this work may not be the best tool for protein structure refinement.

Figure 1.

Energy versus Cα rmsd from the native structure for the decoys obtained as a result of local energy minimization (red dots) followed by MCM search (the nonred dots).

Figure 2.

Bar diagram of the occurrence frequency of the changes in the Cα rmsd from the native structure of each decoy caused by the MCM search. Δrmsd was computed as the difference between the Cα rmsd of the lowest energy decoy found during the MCM search and the energy-minimized starting conformation.

The results reported in Table I show that the MCM runs improve the discriminative power of ECEPP05/SA compared with the local minimizations; that is, the MCM calculations recognized native-like decoys as the lowest energy ones for 76% (34 proteins) of proteins compared with 67% for local energy minimization. If proteins with different secondary structures, that is, α, β, b, and α/β, are considered separately, the two types of calculations perform in the same way for β and α/β proteins, whereas local energy minimization discriminates native-like decoys for only 6 α-helical proteins compared with 11 for the MCM search.

In general, ECEPP05/SA coupled with MCM calculations performs well, discriminating native-like conformation of 76% of the proteins considered in this work. It is somewhat less successful (~63%) in the case of β-sheet proteins. The number of β-sheet proteins considered is relatively small (8) compared with that of a (13) or α/β (24) proteins (Table II). Whether the lower success rate obtained for β-sheet proteins using ECEPP05/SA is a result of some limitations of the force field or a consequence of an insufficient number of proteins considered is under investigation and the results will be published elsewhere.

Table 2.

Rmsd (Å) of the lowest energy decoys obtained from MCM runs with the ECEPP05/SA, ECEPP3/OONS and ECEPP05/FAMBEpH force fields a

| ECEPP05/SA |

ECEPP3/OONS |

ECEPP05/FAMBEpH |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 1b | 5c | 10d | 1b | 5c | 10d | 1b | 5c | 10d |

| α/β Proteins | |||||||||

| 1a19 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 15.95 | 10.44 | 10.44 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| 1a68 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 11.53 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| 1acf | 3.66 | 3.05 | 3.04 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 4.28 | 1.40 | 1.16 |

| 1aiu | 1.61 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 2.30 | 1.55 | 1.55 | 1.15 | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| 1bm8 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.66 |

| 1ctf | 1.45 | 1.35 | 1.34 | 6.23 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.24 |

| 1dhn | 1.85 | 1.52 | 1.33 | 18.90 | 1.26 | 0.84 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 |

| 1iib | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 1.02 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| 1kpe | 1.51 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 8.06 | 7.55 | 7.55 | 7.82 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| 1lou | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 16.44 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| 1opd | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| 1pgx | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.51 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 1.10 | 0.83 | 0.75 |

| 1rnb | 2.06 | 1.70 | 1.10 | 14.41 | 13.07 | 1.13 | 2.06 | 1.10 | 0.96 |

| 1tig | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 11.65 | 11.45 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| 1ubi | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 1ugh | 1.55 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 8.31 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| 1vcc | 1.65 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| 2chf | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.89 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| 1ew4 | 1.45 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 9.94 | 6.36 | 6.36 | 1.82 | 1.82 | 1.37 |

| 1hz6 | 3.66 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 3.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| 1scj | 7.73 | 6.40 | 6.40 | 8.43 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 7.73 | 6.40 | 6.40 |

| 2ci2 | 9.60 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 10.07 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| 4ubp | 9.27 | 8.53 | 7.24 | 10.49 | 9.22 | 8.91 | 9.39 | 1.26 | 1.26 |

| 5cro | 8.34 | 8.34 | 7.17 | 8.15 | 8.15 | 0.67 | 9.00 | 8.04 | 0.71 |

| α Helical proteins | |||||||||

| 1a32 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1.48 | 1.14 | 1.14 |

| 1ail | 3.77 | 3.06 | 1.38 | 1.35 | 1.19 | 1.13 | 1.52 | 1.39 | 1.38 |

| 1bgf | 10.74 | 1.18 | 1.12 | 12.32 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 10.74 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| 1bkr | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 11.56 | 11.56 | 10.76 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.75 |

| 1cg5 | 1.34 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 16.86 | 14.79 | 14.02 | 1.29 | 1.24 | 1.24 |

| 1e6i | 1.34 | 1.29 | 1.09 | 1.20 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.34 | 1.34 | 1.13 |

| 1enh | 2.74 | 2.19 | 2.19 | 3.65 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.15 |

| 1eyv | 1.68 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 13.76 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 9.98 | 9.54 | 1.14 |

| 1lis | 1.24 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 10.65 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.24 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| 1r69 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 1.92 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| 1cei | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.91 | 10.83 | 8.52 | 8.52 | 11.84 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| 1utg | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.63 | 6.05 | 3.14 | 1.72 | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.57 |

| 1vls | 10.67 | 6.69 | 1.80 | 10.34 | 7.74 | 4.71 | 9.93 | 5.35 | 5.35 |

| β Proteins | |||||||||

| 1fna | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 1.08 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| 1shf | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| 1ten | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| 1tul | 1.16 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 1.07 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| 1who | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| 1bk2 | 7.36 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 7.27 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 7.09 | 0.71 | 0.61 |

| 1gvp | 15.04 | 10.87 | 10.60 | 16.84 | 10.88 | 6.96 | 14.47 | 10.38 | 8.36 |

| 1vie | 6.41 | 6.41 | 6.39 | 8.73 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 6.70 | 6.70 | 6.26 |

Incorrectly identified entries are marked in bold face

Cα rmsd of the lowest-energy conformation

Cα rmsd’s of the 5 lowest-energy conformation.

Cα rmsd’s of the 10 lowest-energy conformation.

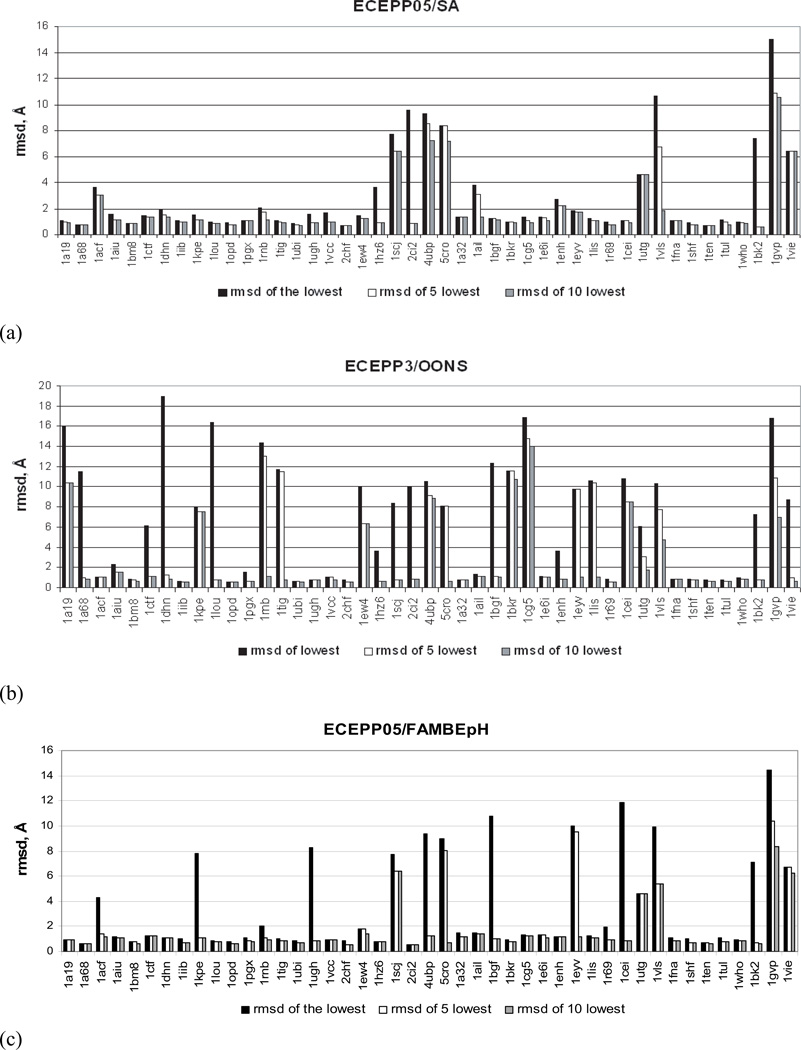

If 5 and 10 lowest energy conformations, obtained after clustering of the MCM results, are considered, the percentage of discriminated proteins increases to 84 and 87%, respectively [columns 3 and 4 of Table II, Fig. 3(a)]. Comparison with other works,12,21,23,26,27 in which relaxation methods were used for scoring, shows that the ECEPP05/SA scoring function is one of the best in discriminating native-like conformations. Thus, the scoring function, applied by Verma and Wenzel12 to the Rosetta decoy set and which shares similarity with ECEPP05/SA (both of them being based on torsional angle representation and employing a SA model to treat solvation effects), succeeded in only 78% of the cases when the top 10 scoring-conformation criterion was used.

Figure 3.

Rmsd of the lowest-energy decoy (black bars), the lowest rmsd decoy from the top 5 decoys selected by the total energy (white bars), the lowest rmsd decoy from the top 10 decoys selected by the total energy (grey bars): (a) ECEPP05/SA; (b) ECEPP3/OONS; (c) ECEPP05/FAMBEpH.

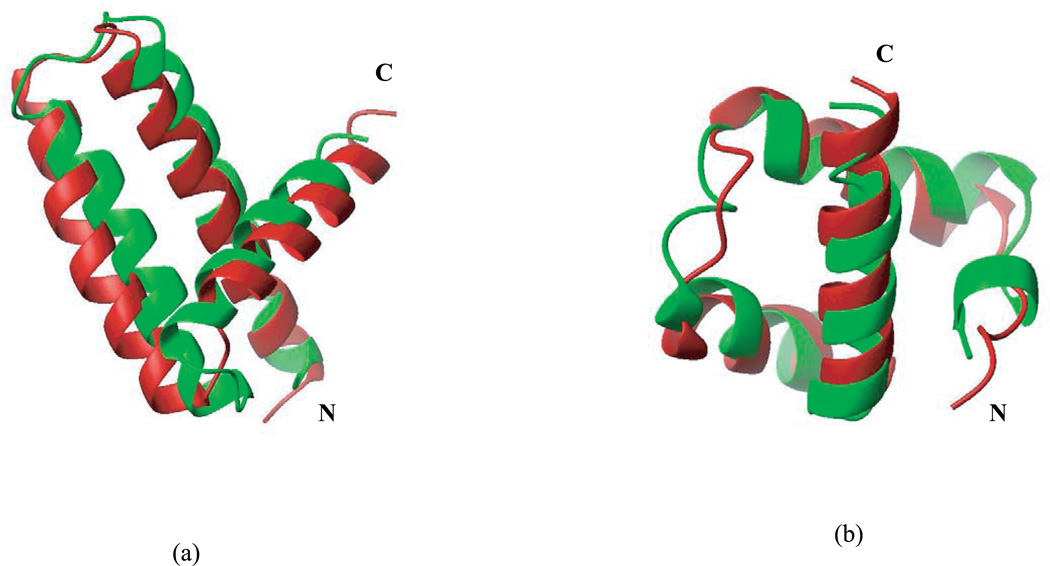

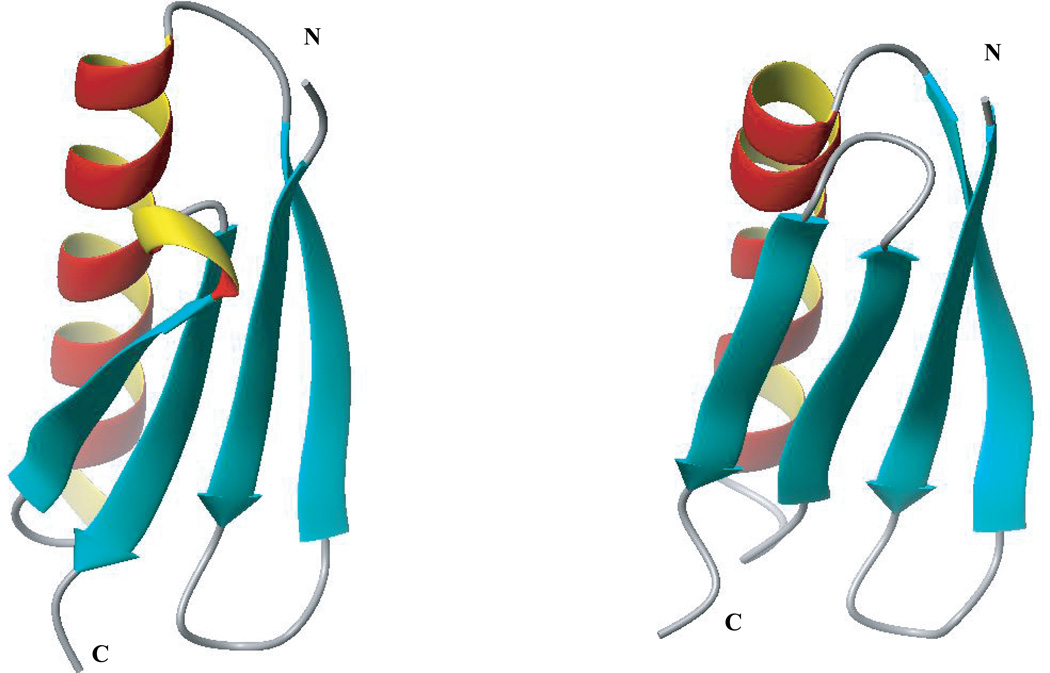

For the proteins for which ECEPP05/SA recognized native-like decoys as the lowest-energy ones, the average rmsd of those lowest energy structures is 1.39 Å with the rmsd’s of the majority of the individual proteins below 2 Å [Table II, Fig. 3(a)]. The only exceptions are 1acf (3.66 Å), 1rnb (2.06 Å), 1ail (3.77 Å), and 1enh (2.74 Å). Despite the relatively high rmsd of the lowest-energy decoys of these four proteins, there is still significant similarity of the tertiary structure of these models and the corresponding experimental conformations, as illustrated in Figure 4 for 1ail and 1enh (two proteins with the largest rmsd per residue).

Figure 4.

Overlay of the ECEPP05/SA lowest energy decoy (green) and the native structure (red) for (a) 1ail (rmsd = 3.77 Å) and (b) 1enh (rmsd = 2.74 Å).

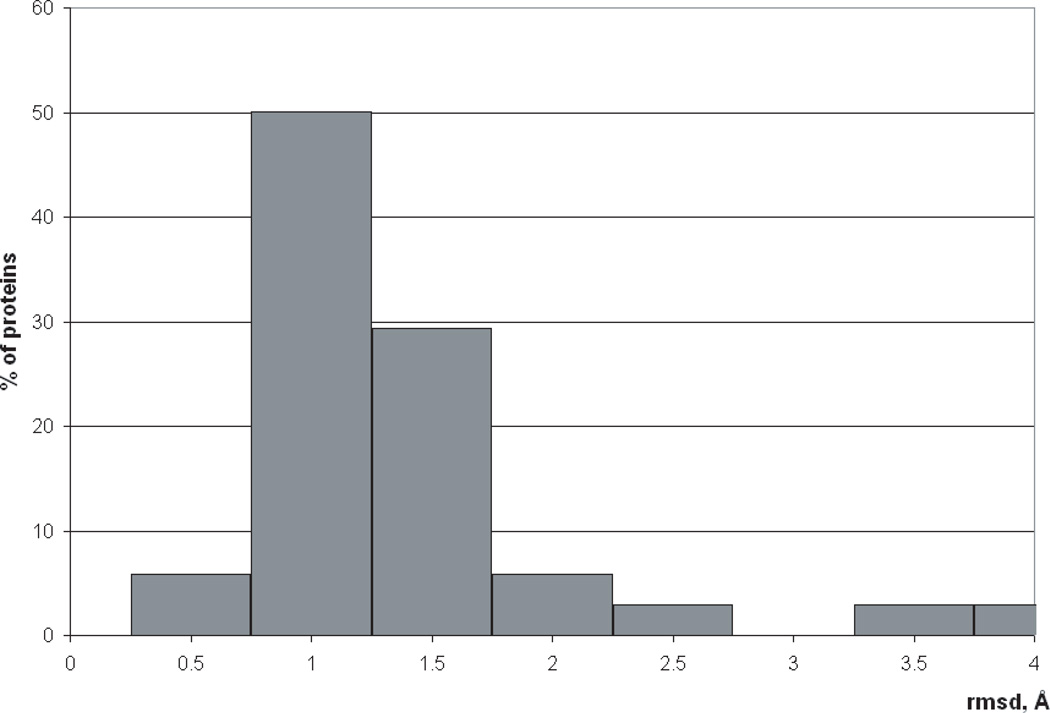

If we consider only native-like decoys of all 45 proteins (defined as those with rmsd’s below 4 Å), 96% of these proteins have the lowest-energy native-like structure with rmsd ⩽2 Å (see Fig. 5). This result suggests that the ECEPP05/SA force field may be used for protein refinement provided that the starting models are sufficiently close to the native structure and an efficient search method is available.

Figure 5.

Percentage of proteins with native-like decoys as stated on p.13 which have lowest-energy native-like structures with rmsd within a given range.

Some studies27 demonstrated that intramolecular or van der Waals energy alone has better discriminative ability than the total energy. It was also suggested53 that because it is often unknown whether the given sequence is a part of a larger oligomeric structure, a solvation energy term would unnecessarily penalize the exposed binding areas of the protein surface. Analysis of the intra-molecular and van der Waals energies carried out for the decoy set obtained after the MCM search showed that neither of them performs better than the total ECEPP05/ SA energy. It should be mentioned that although the total energy is an accurate indicator of native-like conformations for 78% of the proteins, there is no strong correlation (correlation coefficient r = 0.48 ± 0.18) between the total energy and rmsd. This result is caused by the ruggedness of the all-atom energy surface and is in line with the earlier observations.23,25,31

Performance of the ECEPP3/OONS scoring function

To assess whether ECEPP05/SA is more accurate than the earlier version of the ECEPP force field, we carried out MCM calculations after energy minimization with the ECEPP3 force field combined with the OONS surface area solvation model. The results are reported in columns 5–7 of Table II and Figure 3(b). On average, ECEPP05/ SA is superior to ECEPP3/OONS. These two force fields discriminate native-like decoys as those with the lowest free energy for 76 and 42% of the proteins, respectively. If we consider the 5 and 10 decoys with the lowest ECEPP3/OONS energy (columns 6 and 7 of Table II), the percentage of recognized proteins increases to 71 and 80%, respectively, which is still lower than the corresponding values for ECEPP05/SA. The ECEPP05/SA scoring function is more accurate for both α (77% vs. 31%) and α/β (79% vs. 42%) proteins and behaves in the same way as ECEPP3/OONS for β-sheet proteins.

We also carried out an analysis of the performance of the scoring functions including only some of the terms of the ECEPP3/OONS force field. Thus, the ECEPP/3 intramolecular or van der Waals energies were used for scoring. When the decoy set obtained after the MCM search with ECEPP3/OONS was considered, native-like structures of ~56% of proteins were recognized as those with the lowest intramolecular energy. The same success rate was obtained for the van der Waals term, which is not surprising because this term accounts for >70% of the ECEPP/3 intramolecular energy.

The better performance of the ECEPP05/SA potential compared with ECEPP3/OONS may indicate that the parameter optimization37 carried out using protein decoys and by considering the entire force field (i.e., intramolecular and solvation energies) has advantages over combining different energy terms parameterized independently, at least for simple solvation models.

Performance of ECEPP05/FAMBEpH compared with the ECEPP05/SA and ECEPP3/OONS scoring functions

The scoring function including the ECEPP05 force field and the FAMBEpH solvation model performed similarly to ECEPP05/SA, that is native-like decoys of 69% of proteins (31 of 45) had the lowest free energies (column 8, Table II). However, a comparison based on 5 and 10 lowest-energy decoys yielded the success rate of 84 and 89% (columns 9 and 10 of Table II), respectively, as opposed to 84 and 87% for ECEPP05/SA.

For most of the discriminated proteins, ECEPP05/ FAMBEpH distinguished native-like structures which are closer to the native conformations (i.e. with lower rmsd) than the corresponding native-like decoys distinguished by ECEPP05/SA [Table II, Fig. 3(c)]. Thus, an average rmsd of the lowest-energy native-like decoys is 1.32 Å which is slightly lower than the corresponding value (1.47 Å) for ECEPP05/SA. Only for 1r69, did the lowest-energy native-like decoys have significantly higher rmsd’s than the corresponding lowest-energy ECEPP05/SA decoys.

When individual proteins are considered, it can be seen that the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH results are quite different from those produced by either ECEPP05/SA or ECEPP3/OONS [Table II, Fig. 3(c)]. Thus, native-like decoys of 4ubp (a protein for which neither ECEPP05/SA nor ECEPP05/OONS was successful) were discriminated by the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH force field as one of the 10 lowest-energy conformations. On the other hand, non-native decoys of 1vls had lower ECEPP05/FAMBEpH energy than any of native-like conformations, in contrast with the results obtained using ECEPP05/SA (column 10 of Table II).

Failure of the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function to discriminate native like conformations of 1acf, 1kpe, 1ugh, 1scj, 4ubp, 5cro, 1bgf, 1eyv, 1cei, 1utg, 1vls, 1bk2, 1gvp, and 1vie (column 10 of Table II) as those with the lowest energy may be caused by a number of factors from insufficient accuracy of some terms of the energy function [Eq. (2)] to physical reasons, such as involvement of a given protein sequence in interactions with ligands or other proteins (i.e., it may be a part of an oligomer). It should also be noted that single energy evaluation, used for scoring with ECEPP05/FAMBEpH, may not provide a realistic representation of the free-energy surface, especially if a relatively small number of decoys is considered.

All the computations with the FAMBEpH method were carried out assuming that the pH is 7.0. These computations may predict lower stability for native-like decoys compared with non-native conformations if a given protein structure was solved at a very different pH. A review of the crystallization conditions for the proteins from Table II showed that the pH range, for the proteins for which the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function failed to discriminate native-like decoys is 6–8 and, therefore, the wrong pH value can be ruled out as a possible reason for the higher free energy of the native-like conformations obtained for these proteins.

Another possible reason for the poor performance of ECEPP05/FAMBEpH for some proteins is that these proteins may exist under the experimental conditions as a part of an oligomeric structure with a large hydrophobic interface. Such a situation would result in lower free energies of non-native decoys compared with native-like structures. Table III lists proteins which are known to be part of an oligomer in the crystal and/or in solution. Native-like structures of only four proteins from Table III were discriminated by the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function. At least three of these four proteins are part of an oligomer with mostly polar interface or with monomer–monomer interactions mediated by water molecules. This result may suggest that the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function is accurate enough to detect structural features of proteins which exist as oligomers.

Table 3.

Proteins that are Known to Exist as Part of a Larger Molecular Aggregate.

| PDB code | ECEPP05/SA | ECEPP05/FAMBE | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a68 | Yes | Yes | Part of tetrameric ion channel with polar interactions between monomers |

| 1ail | Yes | Yes | Dimer in crystal and in solution with hydrogen-bonds and water molecules at the interface |

| 1bgf | No | No | Dimer in solution; physiologically relevant dimers in crystal with extensive polar interface, hydrogen-bonds |

| 1cg5 | Yes | Yes | Tetramer |

| 1dhn | Yes | Yes | Part of an octamer (hydrogen-bonds, salt bridges and hydrophobic contacts) |

| 1eyv | Yes | No | Dimeric both in solution and in the crystal |

| 1gvp | No | No | Dimer with electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions |

| 1kpe | Yes | No | Dimers connected by a salt bridge. Protomer interactions form an extensive and common hydrophobic core. |

| 1scj | No | No | Part of a complex |

| 1ugh | Yes | No | Complex with Ugi bound to another chain via shape and electrostatic complimentarity, specific charged hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic packing. |

| 1utg | No | No | Dimer with intermolecular disulfide bonds |

| 1vls | No | No | Aspartate binding dimer |

| 1vie | No | No | Tetramer, part of an active site built of 4 monomers |

| 5cro | No | No | Dimer in solution |

‘yes’ or ‘no’ indicates whether a scoring function recognized or did not recognize native-like structures of a given protein as those with the lowest free energy.

The same analysis carried out for ECEPP05/SA (Table III) is less conclusive. Thus, only 6 of 10 proteins which were not discriminated by this scoring function are parts of oligomeric structures. The single chain proteins are 1hz6, 2ci2, 4ubp, and 1bk2. Failure to discriminate native-like decoys of these proteins as those with the low-free energy (the lowest or within 10 lowest-energy conformations) indicates some inaccuracy of the ECEPP05/SA scoring function. The source of the inaccuracy may lie in the solvation model used. For example, 1hz6 represents an interesting case. This protein is built of an α-helix packed against a four-stranded β-sheet. The lowest energy native-like (rmsd (0.8–0.9 Å) and non-native (rmsd ≈ 3.7 Å) conformations differ only in the relative position of β-strands 3 and 4 (see Fig. 6). As a result, these two conformations have very similar surface areas (surface area of the native-like decoy is ~1% larger) and intramolecular energies. However, the SA solvation model overstabilizes the non-native conformation with the wrong sequence of β-strands by ~60 kcal/mol. On the other hand, the FAMBEpH model predicts almost the same solvation energies for the native-like and non-native conformations. The native-like conformation with an rmsd of 0.86 Å is ~4 kcal/mol more stable than the lowest-energy non-native decoy because of the slightly more favorable electrostatic and van der Waals interactions. The solvation contribution to the total free energy of the lowest energy decoy of 2ci2 (non-native decoys with rmsd of 9.60 Å) is also significantly overestimated by the SA model compared with the native-like structure, although the latter has more favorable electrostatic and van der Waals energies. The question whether the accuracy of the SA model can be improved further by better parameterization or it is restricted by the inherent limitations of this model will require additional investigation.

Figure 6.

Experimental structure of 1hz6 (a) and the lowest energy decoy selected by the ECEPP05/SA scoring function (b).

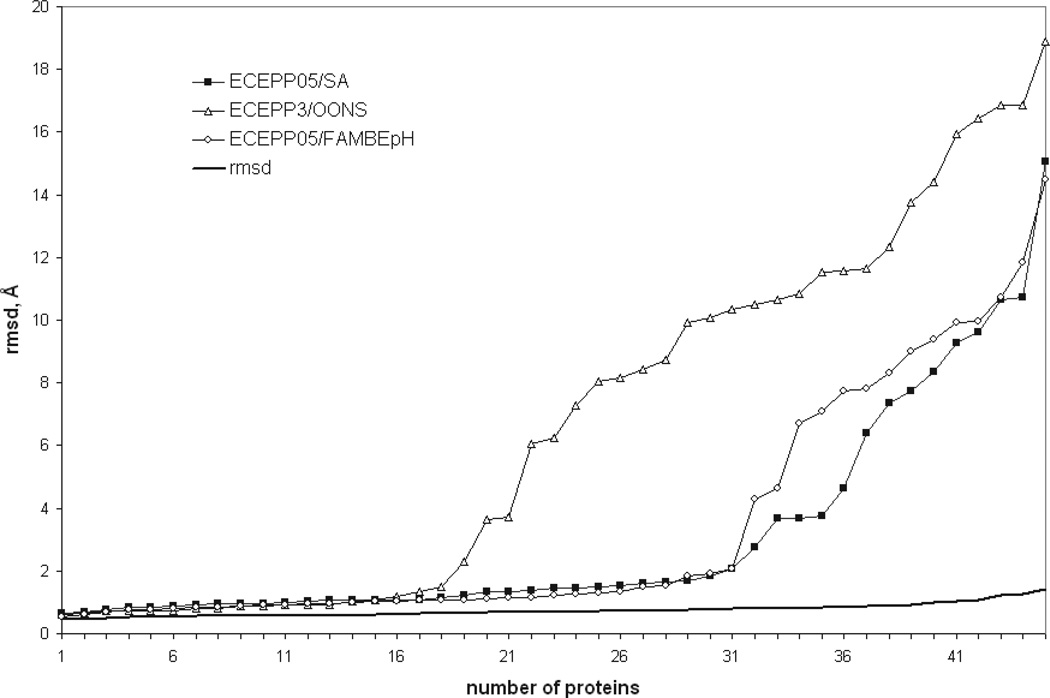

Figure 7 summarizes the results obtained with the ECEPP05/SA, ECEPP3/OONS, and ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function. The best case scenario for a given decoy set is when a given scoring function can discriminate the decoy with the lowest rmsd from the experimental structure as the one that also has the lowest energy (or is one of the 5–10 lowest-energy structures). This ideal case is represented by the solid line in Figure 7. Following the analysis of Tsai et al.,31 we calculated the enrichment of near-native decoys in each decoy set by our different scoring functions; that is the higher the rmsd cutoff considered, the greater is the number of proteins with an rmsd for the lowest-energy decoy below this cutoff. Figure 7 demonstrates the high quality of the decoys sets, that is, each set contains sufficient numbers of near-native conformations (solid line in Fig. 7). It is also clear that ECEPP05/SA performs better than the other two scoring functions as indicated by the filled-square curve which approaches the solid line. On the other hand, we already showed that if the 10 lowest-energy conformations are considered, ECEPP05/FAMBEpH provides slightly better discrimination (89% vs. 87% for ECEPP05/SA) of native-like structures. The discriminative ability of ECEPP05/FAMBEpH which is comparable with that of the much simpler ECEPP05/SA scoring function is surprising, considering the much more accurate description of the complex effects involved in the process of protein solvation provided by the FAMBEpH method. This performance may be a result of energy evaluation (in contrast to energy minimization or MCM run for ECEPP05/SA) used as a scoring method, and may not provide an adequate picture of the free-energy landscape.

Figure 7.

The x-axis is the number of proteins for which the lowest Cα rmsd of five-selected decoys is at or below the Cα rmsd on the y-axis. The line labeled rmsd is the best-case scenario for selecting the lowest Cα rmsd decoy for each protein. Enrichment of the best decoys by Cα rmsd (solid line), total ECEPP05/SA (filled squares), ECEPP3/OONS (open triangles), and ECEPP05/FAMBEpH (open circles) energies.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we have analyzed the performance of several scoring functions based on an ECEPP-type (i.e. torsional angle representation) force field and implicit solvent model. Two of the scoring functions considered here, ECEPP05/SA and ECEPP3/OONS, include an SA solvent model and MCM calculations as a scoring method. ECEPP05/SA was able to discriminate native-like structures with Cα rmsd below 3.5 Å as those within the top 10 lowest-energy conformations for 87% of the proteins and was found to be superior to ECEPP3/OONS. The better performance of the ECEPP05/SA potential compared with ECEPP3/OONS indicates that force-field parameter optimization37 using protein decoys has advantages over combining different energy terms parameterized independently, at least for simple solvation models such as the SA model. In this work, we did not attempt to investigate whether the discriminative ability of the ECEPP05/SA scoring function can be improved further or if it is limited by the nature of the solvent model. This may be the topic of our future research.

Low values of Cα rmsd’s for the low-energy native-like decoys discriminated by ECEPP05/SA suggest that the force field is accurate enough to be used for refinement of protein models when an efficient search method and a reasonable starting model are available. Because our ultimate goal is to obtain high-resolution protein models, we plan to apply the ECEPP05/SA force field to refinement of low- and medium-resolution models produced by using protein structure prediction methods.

Despite the very simple SA solvent model used, ECEPP05/SA can reliably identify near-native conformations and its performance is comparable with or better than that of other existing physics-based scoring functions (involving structure relaxation) which often include computationally more expensive solvent models. Comparison with the scoring function of Verma and Wenzel,12 which also uses an SA model and was parametrized54 to stabilize protein native structures against a large set of non-native decoys, indicates that optimization of the force-field parameters using protein decoys enables one to obtain highly accurate potentials and, therefore, represents a promising tool for force-field development.

The ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function considered in this work is based on a Poisson-Boltzmann solvent model and energy evaluation as a scoring method. This function demonstrated the best performance among all the functions evaluated, that is, near-native conformations of 89% of the proteins have the lowest (i.e. within the 10 lowest-energy structures) ECEPP05/FAMBEpH energy, although it is significantly (~20 times) more CPU demanding than the surface area-based scoring functions (ECEPP05/SA and ECEPP3/OONS). All the proteins for which this scoring function was not able to discriminate native-like structures as those with lowest energy suffer from omission of interdomain interactions. Good performance of the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH scoring function can be rationalized by the high accuracy of the solvent model used and its ability to capture the main effects of the solvation process. Because FAMBEpH can be used so far only in conjunction with energy evaluation, additional investigation is necessary to assess whether this scoring method provides an accurate picture of the free-energy landscape. This work can be carried out when analytical expressions for the first derivatives of the FAMBE solvation free energy become available. An alternative approach may involve Replica Exchange Monte Carlo simulations for small proteins and peptides with the ECEPP05/FAMBEpH potential.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. D. Baker and Dr. R. Das for providing the decoy sets. This research was conducted by using the resources of our 818-processor Beowulf cluster at the Baker Laboratory of Chemistry and Chemical Biology (Cornell University) and the National Science Foundation Terascale Computing System at the Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center.

Grant sponsor: U.S. National Science Foundation; Grant number: MCB05-41633; Grant sponsor: U.S. National Institutes of Health; Grant number: GM-14312; Grant sponsor: Russian Fund for Basic Research; Grant number: 09-04-00136-a.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradley P, Misura KM, Baker D. Toward high-resolution de novo structure prediction for small proteins. Science. 2005;309:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.1113801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das R, Qian B, Raman S, Vernon R, Thompson J, Bradley P, Khare S, Tyka MD, Bhat D, Chivian D, Kim DE, Sheffler WH, Malmström L, Wollacott AM, Wang C, Andre I, Baker D. Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2007;69(Suppl 8):118–128. doi: 10.1002/prot.21636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Kolinski A, Skolnick J. TOUCHSTONE II: a new approach to ab initio protein structure prediction. Biophys J. 2003;85:1145–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Skolnick J. Automated structure prediction of weakly homologous proteins on a genomic scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7594–7599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305695101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher D. 3D–SHOTGUN: a novel, cooperative, fold-recognition meta-predictor. Proteins. 2003;51:434–444. doi: 10.1002/prot.10357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anfinsen CB. Principles that govern the folding of protein chain. Science. 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misura K, Baker D. Progress and challenges in high-resolution refinement of protein structure models. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2005;59:15–29. doi: 10.1002/prot.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu J, Xie L, Honig B. Structural refinement of protein segments containing secondary structure elements: local sampling, knowledge-based potentials, and clustering. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2006;65:463–479. doi: 10.1002/prot.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Summa C, Levitt M. Near-native structure refinement using in vacuo energy minimization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3177–3182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611593104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu H, Skolnick J. Application of statistical potentials to protein structure refinement from low resolution ab initio models. Biopolymers. 2003;70:575–584. doi: 10.1002/bip.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan H, Mark AE. Refinement of homology-based protein structures by molecular dynamics simulation techniques. Protein Sci. 2004;13:211–220. doi: 10.1110/ps.03381404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verma A, Wenzel W. Protein structure prediction by all-atom free-energy refinement. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Brooks CL., III Can molecular dynamics simulations provide high-resolution refinement of protein structure? Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2007;67:922–930. doi: 10.1002/prot.21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Evanseck J, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, III, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminski GA, Friesner RA, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:6474–6487. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. A 2nd generation force-field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic-acids, and organic molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong G, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, Caldwell J, Wang J, Kollman P. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J Comp Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazaridis T, Karplus M. Discrimination of the native from mis-folded protein models with an energy function including implicit solvation. J Mol Biol. 1998;288:477–487. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seok C, Rosen JB, Chodera JD, Dill KA. MOPED: method for optimizing physical energy parameters using decoys. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:89–97. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominy BN, Brooks CL., III Identifying native-like protein structures using physics-based potentials. J Comput Chem. 2002;23:47–160. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MS, Olson MA. Assessment of detection and refinement strategies for de novo proteins structures using force field and statistical potentials. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:312–324. doi: 10.1021/ct600195f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felts AK, Gallicchio E, Wallqvist Levy RM. Distinguishing native conformations of proteins from decoys with an effective free energy estimator based on the OPLS all-atom force field and the surface generalized Born solvent model. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 2002;48:404–422. doi: 10.1002/prot.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MC, Duan Y. Distinguish protein decoys by using a scoring function based on a new AMBER force field, short molecular dynamics simulations, and the generalized Born solvent model. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2004;55:620–634. doi: 10.1002/prot.10470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh M-J, Luo R. Physical scoring function based on AMBER force field and Poisson-Boltzmann implicit solvent for protein structure prediction. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2004;56:475–486. doi: 10.1002/prot.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MC, Yang R, Duan Y. Comparison between Generalized-Born and Poisson-Boltzmann methods in physics-based scoring functions for protein structure prediction. J Mol Model. 2005;12:101–110. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wroblewska L, Skolnick J. Can a physics-based, all-atom potential find a protein’s native structure among misfolded structures? I. Large scale AMBER benchmarking. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:2059–2066. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wroblewska L, Jagielska A, Skolnick J. Development of a physics-based force field for the scoring and refinement of protein models. Biophys J. 2008;94:3227–3240. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vorobjev YN, Almagro JC, Hermans J. Discrimination between native and intentionally misfolded conformations of proteins: ES/IS, a new method for calculating conformational free energy that uses both dynamics simulations with an explicit solvent and an implicit solvent continuum model. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 1998;32:399–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vorobjev YN, Hermans J. Free energies of protein decoys provide insight into determinants of protein stability. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2498–2506. doi: 10.1110/ps.15501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermans J. [Accessed on January 2009];Sigma documentation, University of North Carolina. 2009 Available at: www.chem.duke.edu/~haohu/SIGMA/index.html.

- 31.Tsai J, Bonneau R, Morozov AV, Kuhlman B, Rohl CA, Baker D. An improved protein decoy set for testing energy functions for protein structure prediction. Proteins: Struct Func Bioinform. 2003;53:76–87. doi: 10.1002/prot.10454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [Accessed on May 2008];All Atom Decoy Sets from Rosetta@home. 2007 Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/bakerpg/

- 33.Narang P, Bhushan K, Bose S, Jayaram B. Protein structure evaluation using an all-atom energy based empirical scoring function. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2006;23:385–406. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2006.10531234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnautova YA, Jagielska A, Scheraga HA. A new force field (ECEPP05) for peptides, proteins and organic molecules. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:5025–5044. doi: 10.1021/jp054994x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheraga HA. Theoretical and experimental studies of conformations of polypeptides. Chem Rev. 1971;71:195–217. doi: 10.1021/cr60270a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abagyan R, Totrov M, Kuznetsov D. ICM—a new method for protein modeling and design—applications to docking and structure prediction from the distorted native conformation. J Comp Chem. 1994;15:488–506. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnautova YA, Scheraga HA. Use of decoys to optimize an all-atom force field including hydration. Biophys J. 2008;95:2434–2449. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ooi T, Oobatake M, Nemethy G, Scheraga HA. Accessible surface areas as a measure of the thermodynamic parameters of hydration of peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3086–3090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park B, Levitt M. Energy functions that discrimination X-ray and near-native folds from well-constructed decoys. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:367–392. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Z, Scheraga HA. Monte-Carlo-Minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6611–6615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, Scheraga HAJ. Structure and free-energy of complex thermodynamic systems. Mol Struct (THEOCHEM) 1988;179:333–352. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Némethy G, Gibson KD, Palmer KA, Yoon CN, Paterlini G, Zagari A, Rumsey S, Scheraga HA. Energy parameters in polypeptides. X. Improved geometrical parameters and nonbonded interactions for use in the ECEPP/3 algorithm, with application to praline-containing peptides. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:6472–6484. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vorobjev YN, Vila JA, Scheraga HA. FAMBE-pH: a fast and accurate method to compute the total solvation free energies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:11122–11136. doi: 10.1021/jp709969n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ripoll DR, Vorobjev YN, Liwo A, Vila JA, Scheraga HA. Coupling between folding and ionization equilibria: effects of pH on the conformational preferences of polypeptides. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:770–783. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demchuk E, Wade RC. Improving the continuum dielectric approach to calculating pk as of ionizable groups in proteins. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:17373–17387. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edsall JT, Wyman J. Biophysical chemistry. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1958. p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gay DM. Subroutines for unconstrained minimization using a model trust-region approach. ACM Trans Math Software. 1983;9:503–524. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ripoll DR, Scheraga HA. On the multiple-minima problem in the conformational-analysis of polypeptides. II. An electrostatically driven monte-carlo method-tests on poly(l-alanine) Biopolymers. 1988;27:1283–1303. doi: 10.1002/bip.360270808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ripoll DR, Pottle MS, Gibson KD, Liwo A, Scheraga HA. Implementation of the ECEPP algorithm, the Monte Carlo Minimization method, and the Electrostatically Driven Monte Carlo method on the Kendall Square research KSR1 computer. J Comput Chem. 1995;16:1153–1163. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ripoll DR, Liwo A, Czaplewski C. The ECEPP package for conformational analysis of polypeptides. TASK Q. 1999;3:313–331. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kruskal JB., Jr On the shortest spanning subtree of a graph and the traveling salesman problem. Proc Am Math Soc. 1956;7:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kmiecik S, Gront D, Kolinski A. Towards the high-resolution protein structure prediction. Fast refinement of reduced models with all-atom force field. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herges T, Wenzel W. An all-atom force field for tertiary structure prediction of helical proteins. Biophys J. 2004;87:3100–3109. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]