Abstract

Context: Multiple studies have been conducted on correlates of dietary behavior in adults, but a clear overview is currently lacking. Objective: An umbrella review, or review-of-reviews, was conducted to summarize and synthesize the scientific evidence on correlates and determinants of dietary behavior in adults. Data Sources: Eligible systematic reviews were identified in four databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Only reviews published between January 1990 and May 2014 were included. Study Selection: Systematic reviews of observable food and dietary behavior that describe potential behavioral determinants of dietary behavior in adults were included. After independent selection of potentially relevant reviews by two authors, a total of 14 reviews were considered eligible. Data Extraction: For data extraction, the importance of determinants, the strength of the evidence, and the methodological quality of the eligible reviews were evaluated. Multiple observers conducted the data extraction independently. Data Synthesis: Social-cognitive determinants and environmental determinants (mainly the social-cultural environment) were included most often in the available reviews. Sedentary behavior and habit strength were consistently identified as important correlates of dietary behavior. Other correlates and potential determinants of dietary behavior, such as motivational regulation, shift work, and the political environment, have been studied in relatively few studies, but results are promising. Conclusions: The multitude of studies conducted on correlates of dietary behavior provides mixed, but sometimes quite convincing, evidence. However, because of the generally weak research design of the studies covered in the available reviews, the evidence for true determinants is suggestive, at best.

Keywords: adults, correlates, determinants, diet, dietary behavior, umbrella review

INTRODUCTION

Diet and eating patterns are important for health and prevention of disease.1 Interventions and policies to promote healthy eating are part of public health policies and actions across the globe. Understanding the correlates of dietary behavior is key for the development of those interventions.2–4

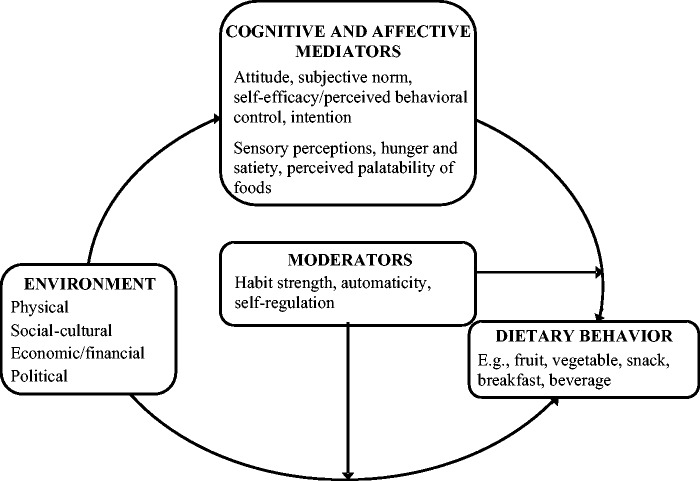

Using empirical research, health-promotion scientists have developed and applied models and theories of behavior change to enable a more systematic and guided study of correlates, to permit types of correlates to be clustered, and to describe the interrelationships between correlates.5 The social-cognitive models and theories that have informed nutrition education interventions (e.g., the Theory of Planned Behavior,6 the Social-Cognitive Theory,7 and the Health Belief Model8) interpret an individual’s dietary behavior to be influenced by the following: 1) beliefs and decisions, 2) rational considerations of pros and cons expected from engaging in the behavior, 3) expected and perceived social influences, and 4) assessment of personal efficacy and control. Additionally, a strong and extensive body of research focused on the physiological correlates and determinants of dietary behaviors has shown that dietary behavior is influenced by hunger and satiety and by affective factors such as sensory perceptions and perceived palatability of foods.9 The importance of the food environment – including the social-cultural (i.e., what is socially accepted and supported) and physical (i.e., what is available and accessible) environment – has been reflected in (social) ecological behavior models such as that described by Booth et al.10

The above insights have been integrated into the so-called environmental research framework for weight gain prevention (EnRG; Figure 1).11 The EnRG is a dual-process model: it postulates that, on the one hand, dietary behavior can be the result of direct “automatic” responses to environmental cues (e.g., meal patterns and routines), and, on the other hand, dietary behavior over time (e.g., cognitive determinants) may be guided by individual’s repeated investment of time and effort into systematically building beliefs about diet and nutrition. The framework further postulates that habits and self-regulation are factors that may moderate the direct and indirect influences of environmental factors on dietary behavior. Analysis of the existing scientific evidence of the relationships between those categories of determinants and dietary behavior may provide valuable insights for health promotion.

Figure 1.

Environmental research framework for weight gain prevention (EnRG). Reproduced from Sleddens et al.12

The purpose of the present study was to provide a comprehensive and systematic overview of the scientific literature on studies of correlates and determinants of dietary behavior in adults. The scientific literature on this topic is extensive and has been documented in a number of systematic reviews that usually focus on only one type of correlate. Of particular interest, however, are the associations among all correlates that are potentially modifiable (social-cognitive, environmental, sensory, and automatic processes) and observable dietary behavior (e.g., fruit consumption, beverage intake, snacking). The aims of this review-of-reviews, a so-called umbrella review, were to explore which correlate-behavior relationships have been studied so far and to assess the importance and strength of the evidence of potential determinants. The findings were categorized within the framework of the EnRG. Parallel to this umbrella review, which focused on adults, a separate umbrella review of studies in children and adolescents was conducted by the same team with the same methodology.12 Some parts of these 2 reviews – especially the description of the theoretical background and methodology – are therefore similar.

METHODS

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

To identify systematic reviews, the bibliographic databases PubMed, PsycINFO (via CSA Illumina), The Cochrane Library (via Wiley), and Web of Science were searched systematically for articles published between January 1, 1990, and May 1, 2014. The search terms included controlled terms, e.g., MeSH in PubMed and Thesaurus in PsycINFO, as well as free-text terms (only in The Cochrane Library). Search terms indicative of food and dietary behavior were used in combination with search terms for determinants, study design (systematic review), study population (humans), and time span (January 1, 1990 to May 1, 2014). The PubMed search strategy can be found in Table 1. The search strategies used in the other databases were based on the PubMed strategy.

Table 1.

Search strategy in PubMed: January 1, 1990, to May 1, 2014 (n = 13,156 citations)a

| Set | Search terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | (“association”[MeSH] OR “association”[tiab] OR “associations”[tiab] OR “determinant”[tiab] OR “determinants”[tiab] OR “correlation”[tiab] OR “correlations”[tiab] OR “correlated”[tiab] OR “correlates”[tiab] OR “relation”[tiab] OR “relations”[tiab] OR “relationship”[tiab] OR “relationships”[tiab] OR “relate”[tiab] OR “related”[tiab] OR “relates”[tiab] OR “factor”[tiab] OR “factors”[tiab] OR “predict”[tiab] OR “predicted”[tiab] OR “prediction”[tiab] OR “predictive”[tiab] OR “predicts”[tiab] OR “predictor”[tiab] OR “associate”[tiab] OR “associates”[tiab] OR “associated”[tiab] OR “influence”[tiab] OR “influences”[tiab] OR “influencing”[tiab] OR “influenced”[tiab] OR “effect”[tiab] OR “effects”[tiab]) |

| #2 | (“food and beverages”[MeSH] OR “food”[tiab] OR “beverage”[tiab] OR “beverages”[tiab] OR “diet”[MeSH] OR “diet”[tiab] OR “eating”[MeSH] OR “eating”[tiab] OR “feeding behavior”[MeSH] OR “feeding behavior”[tiab] OR “feeding behaviour”[tiab] OR “drink”[tiab] OR “sodium chloride, dietary”[MeSH] OR “dietary sodium chloride”[tiab] OR “carbohydrates”[MeSH:noexp] OR “food habit”[tiab] OR “food habits”[tiab] OR “meal”[tiab] OR “meals”[tiab] OR “meal pattern”[tiab]) NOT “dietary supplements”[MeSH]) NOT “food additives”[MeSH]) NOT “micronutrients”[MeSH]) NOT “cannibalism”[MeSH]) NOT “carnivory”[MeSH]) NOT “herbivory”[MeSH]) NOT “bottle feeding”[MeSH]) NOT “breast feeding”[MeSH]) NOT “mastication”[MeSH]) |

| #3 | ”humans”[MeSH] |

| #4 | ”review”[tiab] |

| #5 | (“addresses”[Publication Type] OR “biography”[Publication Type] OR “case reports”[Publication Type] OR “comment”[Publication Type] OR “directory”[Publication Type] OR “editorial”[Publication Type] OR “festschrift”[Publication Type] OR “interview”[Publication Type] OR “lectures”[Publication Type] OR “legal cases”[Publication Type] OR “legislation”[Publication Type] OR “letter”[Publication Type] OR “news”[Publication Type] OR “newspaper article”[Publication Type] OR “patient education handout”[Publication Type] OR “popular works”[Publication Type] OR “congresses”[Publication Type] OR “consensus development conference”[Publication Type] OR “consensus development conference, nih”[Publication Type] OR “practice guideline”[Publication Type]) |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 NOT #5 |

aFilters review; publication data from January 1, 1990, to May 1, 2014 (English)

Studies were included if they met the following criteria, established using the PICOS strategy (see Table 2): 1) studies of observable food and dietary behavior (i.e., consumption behaviors, such as fruit intake and snacking consumption, not purchasing behavior); 2) studies that described potential behavioral determinants of dietary behavior (i.e., factors that may be associated with dietary behavior); 3) study design was a systematic review; 4) studies of healthy adult humans; and 5) studies published between January 1, 1990 and May 1, 2014. The following studies were excluded: 1) studies that were not published in English; 2) studies in which dietary behavior was not an investigated outcome; 3) studies about dietary behaviors in disease management and treatment; 4) studies that focused on specific population groups (e.g., chronically ill, pregnant women, cancer survivors); 5) studies not published as peer-reviewed reviews in scientific journals, e.g., theses, dissertations, book chapters, non-peer-reviewed papers, conference proceedings, reviews of case studies and qualitative studies, design and position papers, and umbrella reviews; 6) reviews of studies of dietary behaviors that were not directly observable (e.g., nutrient or energy intake, appetite); 7) reviews of studies on nonmodifiable correlates (i.e., correlates of the individual’s surroundings that could not be changed, including physiological, neurological, or genetic factors); 8) reviews of studies on the effect of interventions (but reviews of experimental manipulation of single determinants were included); 9) reviews not conducted systematically (i.e., search strategy, including keywords and databases used, was not identified, and/or information on the included studies was insufficient). The current umbrella review focuses on adults and the elderly (>18 y of age). A second umbrella review, conducted using the same methodology, on the correlates of dietary behavior in children and adolescents is published elsewhere.12

Table 2.

PICOS criteria used in the present umbrella review

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Inclusion: presumably healthy adults |

| Exclusion: children and specific adult populations such as chronically ill, pregnant women, or cancer survivors | |

| Intervention/correlate | Inclusion: all kind of determinants of dietary behavior, such as environmental correlates, social-cognitive correlates, economic/financial correlates, political correlates |

| Exclusion: studies that do not address determinants that can be used in policy and practice (i.e. physiology, neurology, genes), nonmodificable correlates, effects of interventions | |

| Comparison | Not applicable, since correlations rather than interventions were investigated |

| Outcome | Inclusion: observable food and dietary behavior (i.e., consumption behaviors, such as fruit intake and snacking consumption) |

| Exclusion: dietary behavior that was not directly observable, purchasing behavior | |

| Study design | Inclusion: systematic reviews describing observational studies that assess potential behavioral determinants of dietary behavior. Reviews of experimental manipulation of single determinants were also eligible |

| Exclusion: randomized control trials, case-control studies, studies about interventions effects or behavior change strategies |

Study selection process

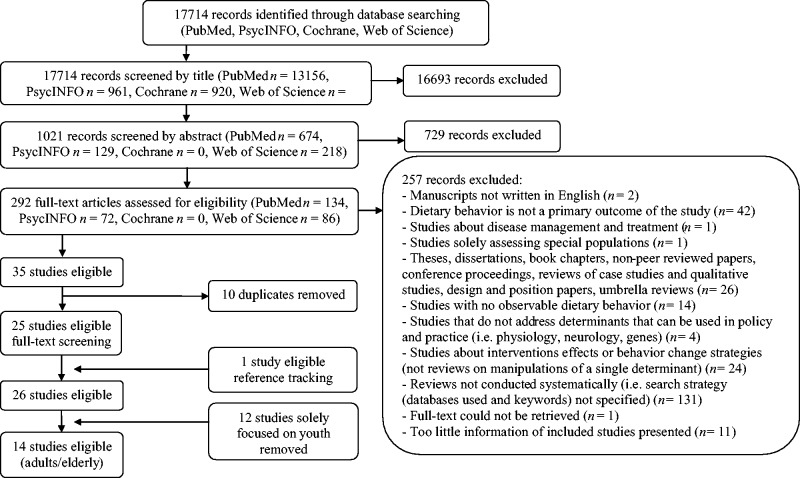

Figure 2 summarizes the manuscript selection process. In total, 17 714 citations were obtained using PubMed (n = 13 156), PsycINFO (n = 961), The Cochrane Library (n = 920), and Web of Science (n = 2677). The subsequent screening of the citations was performed by multiple reviewers (all citations were screened by E.S., almost all citations were screened by W.K., and some were screened by L.M.B., S.P.J.K., and E.V.). All titles of the citations were independently screened for relevance by 2 reviewers (E.F.C.S. and W.K.). Any disagreement was resolved by including the citation in the abstract-screening process. Subsequently, abstracts of the remaining 1031 citations were retrieved for further screening. Another 729 citations were removed, resulting in 292 articles for full-text assessment of eligibility. In case of doubt, potential inclusion was discussed with a third reviewer (S.P.J.K.). Reviews that did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 257) were removed. Reasons for exclusion are shown in Figure 2. Additionally, duplicates (n = 10) were removed. Thereafter, the reference lists of all review papers selected for inclusion (n = 25) were scanned for further relevant references. This reference-tracking technique resulted in one additional review article deemed appropriate for inclusion. In total, 26 reviews were considered eligible. However, of these reviews, 12 were focused on correlates of dietary behavior in youth only (these were examined in a separate umbrella review published elsewhere12). Fourteen reviews were considered eligible for the present umbrella review on correlates of dietary behavior in adults.13–26

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of literature search by database

Data extraction, including rating of methodological quality

In this umbrella review, only findings on the identification and synthesis of the eligible studies (primary literature) as reported in the 14 included systematic reviews are presented. Four authors (E.F.C.S., W.K., L.M.B., and L.F.M.K.) extracted data from the selected reviews. The following data were extracted: search range applied, total number of studies included in the reviews and number of studies included in the reviews that are eligible for the current umbrella review, total number of participants of included studies in the reviews and number of participants of the included studies that are eligible for the current umbrella review, age and continent of included eligible studies, correlate and outcome measures, overall results of the reviews, and overall limitations and recommendations of reviews. Additionally, the methodological quality of the reviews was evaluated using quality criteria adapted from De Vet et al.27 and based on the Quality Assessment Tool for Reviews.28

Eight criteria were each scored as follows (see Table 3): 0 when the criteria was not applicable for the included review, or 1 when the criteria was applicable for the included review. Disagreements between the reviewers on individual items were identified and resolved during a consensus meeting. Therefore, the total quality scores could range from 0 to 8. Reviews with quality scores ranging from 0 to 3 were labeled as weak, those with quality scores between 4 and 6 as moderate, and those with quality scores of 7 or 8 as strong. Furthermore, the importance of the correlates included in the reviews, along with the strength of evidence for each correlate, was assessed in order to give an overview of the important correlates that should be considered in future observational and intervention studies. The importance of a correlate refers to the statistical significance of a potential determinant and/or effect size estimate in relation to a particular type of dietary behavior; in other words, the amount of reviews (or eligible studies within the reviews) that did or did not find statistically significant results. The strength of evidence represents the totality of the evidence. Longitudinal observational studies and – where relevant – experimental studies of sufficient size, duration, and quality that showed consistent effects were given prominence as having the highest-ranking study designs. For this assessment, 2 coding schemes were applied (see Tables 4 and 5, respectively). The criteria for grading evidence were adapted from those of the World Cancer Research Fund.29 The combination of the importance of a correlate and the strength of evidence led to 16 different possible codes. Note that some combinations are self-excluding (i.e., [+/0/−] = convincing evidence, and [−] = limited or no conclusive evidence).

Table 3.

Quality assessment criteria for reviews of correlates of dietary behavior among adults

| Reference | Was there a clearly defined search strategy?a | Was the search strategy comprehensive?b | Were inclusion/exclusion criteria clearly stated? | Were the designs and number of included studies clearly stated? | Was the quality of primary studies assessed? | Did the quality assessment include study design, study sample, outcome measures or follow-up (at least 2 of 4)? | Did the review integrate findings beyond describing or listing findings of primary studies? | Was more than 1 author involved in the data screening and/or abstraction process? | Quality score (sum) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amani and Gill (2013)14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Mills et al. (2013)22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Gardner et al. (2011)17,c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Pearson and Biddle (2011)24,c | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Adriaanse et al. (2011)13,c | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Caspi et al. (2012)16,c | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Moore and Cunningham (2012)23,c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Thow et al. (2010)26 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Giskes et al. (2011)19 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Giskes et al. (2010)18 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Ayala et al. (2008)15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Total | 6/14 | 11/14 | 13/14 | 13/14 | 8/14 | 8/14 | 13/14 | 7/14 |

aA search is rated as “clearly defined” if at least search words and a flowchart were presented.

bA search is rated as “comprehensive” if at least 2 databases and the reference lists of examined papers were searched.

cReviews that also included youth; quality of reviews: weak (n = 1; 7.1%), moderate (n = 9; 64.3%), strong (n = 4; 28.6%).

Table 4.

Definitions of different categories of importance of a determinant

| Category of importance | Definition |

|---|---|

| ++ | The variable was found to be a statistically significant determinant in all identified reviews, without exception. This could mean that only one review included a particular variable and showed that this was a significant correlate and/or reported a (non)significant effect size larger than 0.30, but it could also mean that a number of reviews were conducted that included this variable, and all of them concluded that the variable was significantly related to the particular behavioral outcome |

| + | The variable was found to be a statistically significant determinant and/or reported a (non)significant effect size larger than 0.30 in most reviews or studies within the review, with some exceptions. This implies that >75% of the available reviews concluded the variable was related, or that the separate reviews reported that ≥75% of the original studies concluded the factor was related. This could mean that only one review included a particular variable and showed that this was a significant correlate in >75% of studies, but it could also mean that a number of reviews were executed toward this variable, and most, but not all, concluded the variable was significantly related to the particular behavioral outcome |

| 0 | The variable was found to be a determinant and/or reported a (non)significant effect size larger than 0.30 in some reviews (25%–75% of available reviews or of the studies reviewed in these reviews), but not in others. This could mean that only one review included a particular variable and showed “mixed findings,” but it could also mean that results were mixed across reviews |

| - | The variable was found not to be a determinant, with some exceptions. This implies that <25% of the available reviews or of the original studies in the included reviews concluded that the variable was related. This could mean that only one review included a particular variable and generally showed “null findings,” with some exceptions, but it could also mean that a number of reviews were executed toward this variable, and most, but not all, concluded the variable was not significantly related to the particular behavioral outcome |

| – | The variable was found not to be related to this particular outcome. The absence of an association was identified in all identified reviews, without exception. This could mean that only one review included a particular variable and showed that this correlate was not related to the behavior in question, but it could also mean that a number of reviews were executed toward this variable, and all of them concluded the variable was unrelated to the particular behavioral outcome |

Table 5.

Criteria for grading evidence (see World Cancer Research Fund29 for the full list)

| Strength of evidencea | Definition |

|---|---|

| Convincing evidence | Evidence is based on studies of determinants that showed consistent associations between the variable and the behavioral outcome. The available evidence is based on a substantial number of studies, including longitudinal observational studies and, where relevant, experimental studies of sufficient size, duration, and quality showing consistent effects. Specifically, the grading criteria include evidence from more than one study type, and evidence from at least two independent cohort studies should be available, along with strong and plausible experimental evidence |

| Probable evidence | Evidence is based on studies of determinants that showed fairly consistent associations between the variable and the behavioral outcome, but there are either shortcomings in the available evidence or some evidence to the contrary, which precludes a more definitive judgment. Shortcomings in the evidence may be any of the following: insufficient duration of studies, insufficient studies available (but evidence from at least 2 independent cohort studies or 5 case-control studies should be available), inadequate sample sizes, incomplete follow-up |

| Limited, suggestive evidence | Evidence is based mainly on findings from cross-sectional studies. Insufficient longitudinal observational studies or experimental studies are available, or results are inconsistent. More well-designed studies of determinants are required to support the tentative associations |

| Limited, no conclusive evidence | Evidence is based on findings of a few studies that are suggestive but are insufficient to establish an association between the variable and the behavioral outcome. No evidence is available from longitudinal observational or experimental studies. More well-designed studies of determinants are required to support the tentative associations |

aIdeally, the definition of the strength of evidence should be based on a relationship that has been established by multiple randomized controlled trials of manipulations of single isolated variables, but this type of evidence is often not available. The criteria used to describe the strength of evidence in this report are based on the criteria used by the World Cancer Research Fund29 but have been modified for the research question at hand. Four categories were defined: convincing; probable; limited; suggestive; and limited, no conclusion.

RESULTS

Description of reviews

Quality assessment ratings are presented in Table 3. One review received a quality score of 2 (weak quality).16 Nine of the 14 reviews received a score indicating moderate quality,13–15,18,19,23–26 and 4 received a score indicating strong quality.17,20–22 In most reviews (13 of 14), the inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly stated,13,15–26 the designs and number of included studies were clearly stated,13–15,17–26 and the review did integrate findings beyond merely describing or listing the findings of primary studies.13,14,16–26 Clearly defined search strategies were often absent in the reviews (8 of 14), as usually a flowchart of the data screening process was missing.13,14,16,18,19,21,24,25

Table 6 provides an overview of the characteristics of the included reviews. The number of studies included in the separate reviews ranged from 414,23 to 35.25 In 2 reviews, all included studies were eligible for the present umbrella review21,25; the reasons for noneligibility of studies in the included reviews were most often a focus on children and/or adolescents or a focus on nonobservable dietary behavior. In most included reviews, the studies reviewed were cross-sectional studies.15,16,18–21,23–25 The total sample size of the studies included in the different reviews varied from more than 250 to more than 330 000.16,18,21 There were few studies of elderly populations (>65 y) in the included reviews, but age was often not reported. The majority of the studies in the included reviews were conducted in North America, followed by (Western) Europe and Australasia (see Table 5).

Table 6.

Characteristics of analyzed systematic reviews of studies conducted in adults

| Reference | Search range applied | No. of eligible studies included in the review/total no. of studies included in the review | Study designa | Total sample size of eligible studies included in the review/total sample size of all studies included in the review | Age of population | Continent or region, no. of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amani and Gill (2013)14 | From 1990 to May 2011 | 4 studies from 4 articles/16 studies from 15 articles | Cross-sectional, n = 1; longitudinal, n = 3 | Total n = 255, range 16–137/Total n = 33 530, range 16–27 485 | >18 y (working population) | NR, n = 2; Asia, n = 1; South America, n = 1 |

| Mills et al. (2013)22 | NR (published between 1980 and 2012) | 5 studies/9 studies | Intervention, n = 5 | Total n = 401, range 40–125/Total n = >808, range 40–227 | >18 y | Europe and North America |

| Gardner et al. (2011)17 | Up to January 29, 2011 | 9 studies (10 samples)/22 studies (21 samples) | Cross-sectional, n = 2; longitudinal, n = 7 | Total n = 3596, range 93–876/Total n = 4344, range 93–876 | University staff, students, adults, employees | North Amercia, n = 1; Europe, n = 8 |

| Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | Up to early 2010 | 8 studies (9 samples)/11 studies (14 samples) | Cross-sectional, n = 5; longitudinal, n = 3 | Total n = NR, range 500–>5000/Mean n = 11 044, range 74–50 277 | >18 y | North America, n = 7; Europe, n = 1 |

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Up to July 28, 2009 | 22 studies/23 studies | Cross-sectional, n = 17; longitudinal, n = 5 | Total n = 33 836, range 144–16 287/Total n = 34 577, range 144–16 287 | 18–65 y | North America, n = 15; Europe, n = 7 |

| Adriaanse et al. (2011)13 | Up to December 2009 | 18 studies from 16 articles/24 studies from 21 articles | Healthy eatingb cross-sectional, n = 1; longitudinal, n = 3; intervention, n = 11 | NR/NR | Students and adults >18 y | NR |

| Unhealthy eatingb:longitudinal, n = 1; intervention, n = 8 | ||||||

| Caspi et al. (2012)16 | Up to March 2011 | 31 studies/38 studies | Cross-sectional, n = 28; intervention, n = 3 | FV intake: total n = NR, range 102–568 584; fast food intake: total n = NR, range 415–6759/FV intake: total n = NR, range 102–568 584; fast food intake: total n = NR, range 415–6759 | Adults | North America, n = 20; Australasia, n = 7; Europe, n = 3; Asia, n = 1 |

| Moore and Cunningham (2012)23 | From 1983 to July 2011 (based on publication years of included studies) | 4 studies/14 studies | Cross-sectional only | Total n = 75 890, range 193–64 277/Total n = 89 086, range 51–64 277 | 35–55 y, 21–55 y, 20–64 y, 30–74 y | North America, n = 2; Europe, n = 1; Asia, n = 1 |

| Thow et al. (2010)26 | NR (published between 2000 and 2009) | 6 studies/24 studies; 8 empirical studies and 16 modeling studies | Predictive modeling, n = 4; empirical, n = 2 | NR/NR | Adults | North America, n = 4; Europe, n = 2 |

| Giskes et al. (2011)19 | From 2005 to 2008 | 17 studies/28 studies (of 23 samples; 5 sourced from 2 study populations) | Cross-sectional, n = 16; intervention, n = 1 | Total n = 73 935, range 102–20 527/Total n = 860 569, range 102–714 054 | Adults | North America, n = 8; Europe, n = 2; Australia/New Zealand, n = 6; Asia, n = 1 |

| Giskes et al. (2010)18 | From 1990 to 2007 | 24 studies/47 studies (39 samples) | Cross-sectional, n = 23; longitudinal, n = 1 | Total n = 368 305, range 297–41 446/Total n = 497 843, range 297–69 383 | Adults | Europe only |

| Ayala et al. (2008)15 | From 1965 to 2007 | 11 studies (from the 24 quantitative studies)/34 studies | Cross-sectional only | Total n = 47 955, range 76–42 951/Total n = 85 332, range 76–42 951 | Adults | North America only |

| Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | From 1994 to 2006 | 35 studies/35 studies | Cross-sectional, n = 21; longitudinal, n = 14 | Cross-sectional: total n = 26 100, range 151–3557; longitudinal: total n = 13 869, range 146–3122/Cross-sectional: total n = 26 100, range 151–3557; longitudinal: total n = 13 869, range 146–3122 | >18 y | North America, n = 22; Europe, n = 13 |

| Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | From January 1, 1980, to December 31, 2004 | 24 studies/24 studies | Cross-sectional only | Total n = 332 632, range 63–142 715/Total n = 332 632, range 63–142 715 | Adults | North America, n = 7; Europe, n = 15; Australia, n = 2 |

Abbreviations: FV, fruit and vegetable; NR, not reported (the focus was mainly on providing a more thorough description of the eligible studies within the included reviews, e.g., study design, age of population, continent of study).

aCross-sectional, longitudinal observational, case control, and intervention studies (experimental, behavioral laboratory, field studies in which interventions were studied).

bNumber of included studies, not eligible studies.

Findings of the reviews

Table 7 provides an overview of the correlates and outcomes (i.e., observable dietary behaviors) in the included systematic reviews, along with the overall findings, limitations, and recommendations reported by the authors of the reviews. The next section provides an overview of the correlate-behavior relationships that have been studied thus far and gives an overview of the importance and the strength of evidence of potential determinants.

Table 7.

Results of reviews about correlates of dietary behavior among adults

| Reference | Outcome measures | Correlate measures | Overall results of reviewa | Limitations of reviewa | Recommendations of reviewa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amani and Gill (2013)14 | Consumption of snacks, sweets, and breakfast. In the 4 eligible studies, 6-d food diaries, 24-h recalls, and self-registered food consumption records were used, along with a photographic method | Shift work | Most studies show that shift work affects nutritional intake negatively (higher snack and sweets consumption, low breakfast) in shift workers | Most studies were cross-sectional. Most studies relied on self-reported weight and height. Difficult to maintain homogeneity between shift-work group and control group for years on shift, age, and medical conditions | Need more practical and specialized recommendations to meet shift workers’ nutritional requirements in different settings with various conditions. This should be highlighted in every long-term industrial strategic plan. Greater use of nutritional frameworks for interventions that acknowledge the complexity of the environment and specific nutritional requirements is suggested. Lifestyle patterns should be addressed in greater detail |

| Mills et al. (2013)22 | Snack food consumption, soda consumption. The dietary intake measures used were not reported | Food advertisements | The results did not show conclusively whether food advertising affects food-related behavior | Process of randomization was not described in any study. Quality appraisal revealed mixed results. Most studies conducted on a small scale. Details on socioeconomic position and ethnicity were rarely provided. Most studies relied on self-referral of participants. As all studies were experimental, and participants were aware of involvement in a research project | Research should also be undertaken in less economically developed areas. Important to conduct studies involving older people. Review of observational studies with longer-term follow-up necessary. Assess the potential effects of food advertising delivered through other means. Explore the effects of broader food-promotion activities. The use of standardized measurement tools and consistent outcome reporting between studies needs to be encouraged |

| Gardner et al. (2011)17 | Fruit consumption; snack, sweets, or chocolate consumption; sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Majority of studies used self-report measures, 2 studies used objective behavior measures (observed food choice in a lab setting) | Habit strength | The weighted habit–behavior correlation effect estimate for nutritional habits was moderate to strong in size (fixed: r+ = 0.43; random: r+ = 0.41), and effects were of equal magnitude across healthful (fixed: r+ = 0.43; random: r+ = 0.42) and unhealthful (fixed: r+ = 0.42; random: r+ = 0.41) dietary habits. The medium-to-large grand weighted mean habit–behavior correlation (r+ ≈ 0.45) suggests that habit alone can explain about 20% of variation in nutrition-related behaviors (i.e., R2 ≈ 0.20) | While it was not possible to meta-analyze interaction effects, habit often moderated the relationship between intention and behavior, such that intentions had a reduced effect on behavior where habit was strong. This finding must be interpreted cautiously because it may reflect a bias toward publication of studies that find significant interaction, and the robustness of this effect may be overestimated. Many studies were cross-sectional and thus modeled habit as a predictor of past behavior. This fails to acknowledge the expected temporal sequence between habit and behavior and is also conceptually problematic given that, at least in the early stages of habit formation, repeated action strengthens habit. Reports of behavior relied on self-reports | Explorations of the role of counter-intentional habits on the intention–behavior relationship, such as the capacity for habitual snacking to obstruct intentions to eat a healthful diet, are needed. Healthful behaviors can habituate. The formation of healthful (“good”) habits, so as to aid maintenance of behavior change, thus represents a realistic goal for health-promotion campaigns. More methodologically rigorous research is required to provide more conceptually coherent and less biased observations of the influence of habit on action. A more comprehensive understanding of nutrition behaviors, and how they might be changed, will be achieved by integrating habitual responses to contextual cues into theoretical accounts of behavior |

| Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | Intake of fruit, vegetables, FV, energy-dense snacks, fast foods, energy-dense drinks, healthy snacks, sweets/desserts. Majority of studies used self-report measures, with FFQs being the measure used most frequently | Sedentary behavior: screen time (TV/video/DVD viewing, computer use), total inactivity, TV viewing | The association drawn mainly from cross-sectional studies is that sedentary behavior, usually assessed as screen time and predominantly TV viewing, is associated with unhealthy dietary behaviors in children, adolescents, and adults. There appears to be no clear pattern for age acting as a moderator. There appears to be more consistent associations between sedentary behavior and diets for women/girls than for men/boys | Many studies were cross-sectional. Use of self-reported measures of sedentary and dietary behaviors that lack strong validity. Sedentary behavior is largely operationally defined as screen time, which is mainly TV viewing, making it diffıcult to draw conclusions about nonscreen time and dietary intake. Although “screen time” can include TV and computer use, this term does not help identify whether it is TV watching, computer use, or both that are associated with unhealthy diets | More studies using objective measures of sedentary behaviors and more valid and reliable measures of dietary intake are required. Examine the longitudinal association between sedentary behavior and dietary intake, and track the clustering of specifıc sedentary behaviors and specifıc dietary behaviors. For example, it appears from the mainly cross-sectional evidence presented that TV viewing is associated with unhealthy dietary patterns. Much less is known about diet and either computer use or sedentary motorized transport. It is likely that the main associations will be with TV, but this needs testing. A focus on sedentary behaviors and dietary behaviors that “share” determinants as well as determinants of the clustering of sedentary and dietary behaviors will aid the development of targeted interventions to reduce sedentary behaviors and promote healthy eating |

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Fruit and/or vegetable intake. Majority of studies used validated instruments to measure dietary intake, mainly FFQs or multiple-item questionnaires | Habit, motivation and goals, beliefs about capabilities, knowledge, beliefs about consequences, social influences, context and life experiences, taste, socio-demographic variables, social role and identity, health value, behavioral regulation | The random-effect R2 observed for the prediction of FV intake was 0.23. A number of methodological moderators influenced the efficacy of prediction of FV intake. The most consistent variables predicting behavior were habit, motivation and goals, beliefs about capabilities, knowledge, and taste. Overall, the proportion of variance explained for FV intake, fruit intake, and vegetable intake was, respectively, 23%, 19%, and 14% | The small number of studies included limits the robustness of the findings. Publication bias might bias the sample and account for some of the effects that were observed. None of the studies included in this review compared the efficacy of different theories to predict FV intake, and very few studies compared different theories empirically. A theory is successful when the explained variance is the highest. However, in using other criteria of success (e.g., intervention value, clinical meaningfulness, population, or cultural specificity, parsimony), other conclusions could have been reached. The most consistent variables associated with behavior or intention were identified. However, the influence of psychosocial variables on behavior was based on significance ratio and relied on a null hypothesis testing and not on an estimate of the effect size. It was not possible to ascertain whether the theories were used correctly. Constructs may be misinterpreted or poorly measured, and analyses may have been inappropriate | There is an urgent need for sound theoretical research on determinants of FV intake. Future studies should rigorously apply the most effective psychosocial theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior or the Social Cognitive Theory and test for promising but new variables in order to move the field forward. In particular, the role of affective attitude, behavioral regulation, and social identity should be investigated. Differences in the efficacy of prediction according to gender and food category (FV intake, fruit intake, or vegetable intake) should be explored. Future studies should consider methodological aspects such as study design in order to contribute to the development of a significant body of data on FV intake. This review also suggests there is sufficient evidence on determinants of FV intake to guide intervention development. Tailored interventions should target motivation and goals, beliefs about capabilities, knowledge, taste (especially for vegetable intake), and breaking the influence of habit |

| Adriaanse et al. (2011)13 | Fruit and/or vegetable consumption, unhealthy snack consumption, intake of low-fat foods. Different measures were used, including 7-d food diaries, 24-h recalls, and FFQs (short and long forms) | Use of implementation intentions | Considerable support was found for the notion that implementation intentions can be effective in increasing healthy eating behaviors, with 12 studies showing an overall medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.51) of implementation intentions on increasing FV intake. However, when aiming to diminish unhealthy eating patterns by means of implementation intentions, the evidence is less convincing, with fewer studies reporting positive effects, and an overall small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.29) | Used rather weak outcome measures that relied heavily on retrospective recall or assessed food intake over a limited time frame. Results indicate that the overall effect size of studies promoting healthy eating patterns may be inflated due to some studies using less-than-optimal control conditions | Although implementation intention instructions were not included as a moderator in this meta-analysis because of the limited number of studies, it seems prudent that future research take into account the importance of using instructions that support autonomy. Stricter control conditions as well as better outcome measures are required. Investigate efficacy of implementation intentions in diminishing unhealthy eating behaviors. In doing so, future studies should also compare the efficacy of different types of implementation intentions, as these may have differential effects on unhealthy food consumption |

| Caspi et al. (2012)16 | Intake of fruit and/or vegetables, fast food, specific products (e.g., red meat, low-fat milk, processed meats), fats, nonwhite bread, whole grains. Different dietary intake measures were used, including FFQs, 24-h recalls, brief customized screeners, and food diaries | Food environment: 5 dimensions of food access (availability, accessibility, affordability, accommodation, acceptability) | Moderate evidence in support of the causal hypothesis that neighborhood food environments influence dietary health. Perceived measures of availability were consistently related to multiple healthy dietary outcomes. GIS-based measures of accessibility (primarily operationalized as distance to various food stores) were overwhelmingly unrelated to dietary outcomes. GIS-based availability measures, such as store presence and density, were somewhat more promising, although results were mixed | Dietary outcomes and assessment measures varied substantially across studies. In general, studies that show a positive relationship may be more likely to be published than those with null results, suggesting some publication bias | 1) More standardized/validated measures for assessment of food environment needed |

| 2) Develop/refine understudied measures | |||||

| 3) Abandon purely distance-based measures of accessibility, and combine multiple environmental assessment techniques | |||||

| 4) Researchers should continue to expound upon the conceptual definitions of food access as they develop and refine new combinations of measures for the food environment | |||||

| Moore and Cunningham (2012)23 | Daily FV consumption, breakfast consumption. Measurement instruments were not reported | Social status, stress, and BMI | Higher stress is related to less healthy dietary behaviors. The majority of studies also reported that higher social position is related to healthier diet | Only included studies that were published in English. Many studies were cross-sectional. Heterogeneity of measures | 1) More quantitative dietary assessment tools, such as FFQ, repeated 24-h recalls, and food diaries, are needed |

| 2) More longitudinal studies are needed | |||||

| 3) Implementing appropriate monitoring and evaluation is essential to identifying successful, holistic strategies that can be used to improve quality of care | |||||

| Thow et al. (2010)26 | Soft drink demand, soft drink expenditure, soft drink consumption, FV consumption. Measurement instruments were not reported | Food taxes and subsidies | The studies showed that taxes and subsidies on food have the potential to influence consumption considerably and to improve health, particularly when they are large. A reduction in soft drink tax resulted in an increase in average soft drink consumption. From grey literature: 4 studies on a tax on soft drinks found a decrease in soft drink consumption/purchases; 1 study on an FV subsidy found an increase in FV consumption | Inadequate evidence available for informing policy-making. High proportion of modeling studies, which are based on assumptions and subject to data limitations. Many modeling studies analyzed only target food consumption and overlooked shifts in consumption within or across food categories. No experimental studies were available. Wide variations in data sources and analytical methods. Only included studies that were published in English. Majority of the evidence came from high-income countries | The administrative aspects of policy implementation, such as selecting a taxation mechanism, will be important for ensuring that taxes are acceptable. Further research is recommended in four areas: |

| 1) Experimental studies are needed to document actual responses of both prices and consumers to changes in food taxation | |||||

| 2) Future modeling studies should examine changes in the entire diet that result from price changes | |||||

| 3) There is a need for research into consumer responses to food taxes in developing countries | |||||

| 4) Implementation and administrative costs need to be examined, since they represent potential barriers to the feasibility of these interventions | |||||

| Giskes et al. (2011)19 | Fruit and vegetable consumption, vegetable consumption, takeaway or fast food consumption, breakfast consumption, lunch consumption. Different measures were used: FFQs (n = 12), 24-h recalls (n = 4), and diet history (n = 1) | Accessibility factors; social factors, material factors, cultural factors | The findings of studies examining environmental factors in relation to obesogenic dietary behaviors were inconsistent, with mixed associations reported. The only exception to this was area-level deprivation, with residents of socioeconomically deprived areas having a greater likelihood of obesogenic dietary intakes than their counterparts in advantaged areas | The majority of studies included in this review were conducted in the USA, the UK, or Australia/New Zealand. The findings showed that associations between obesogenic dietary behaviors and environmental factors have been studied most frequently for FV intake. Grey literature was excluded. Environmental or dietary intake measures sometimes differed markedly between studies. Little is known about appropriate confounders. Almost all studies were cross-sectional | Investigate environmental influences on all dietary factors that may contribute to obesogenic dietary intakes. Accessibility to supermarkets/take-away outlets and residing in a socioeconomically deprived area are environmental factors that may contribute to overweight or obesity and/or obesogenic dietary behaviors. These factors need to be targeted in multilevel health-promotion interventions and policies aimed at decreasing overweight/obesity. The role of other environmental factors should not be discarded without further investigation. To understand the role of environmental factors, prospective studies that simultaneously examine a broad range of environmental factors, obesogenic dietary behaviors, and physical activity are needed |

| Giskes et al. (2010)18 | Consumption of fruit, vegetables, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Majority of studies used FFQs to measure dietary intake. Other measures used: dietary records, dietary history, 24-h recalls, dietary behavior questions | The following indicators of socioeconomic position were included in this review: education, occupation, and income (either individual or household-level). “Other” measures included in this review were indicators of material resources (e.g., car ownership, housing tenure) or area-based indicators of socioeconomic position (e.g., deprivation characteristics of areas) | Socioeconomically disadvantaged groups consume less FV than their more-advantaged counterparts, and these dietary inequalities are consistent by gender and region. The roles of other proposed obesogenic dietary behaviors, such as intakes of energy-rich drinks, could not be ascertained because they have been relatively understudied in Europe | Only included studies that were published in peer-reviewed journals (electronic databases). Differences in the conceptualization, measurement, and summary of socioeconomic position and/or the dietary factors in the different studies. The dietary outcomes examined in this study were not comprehensive for all nutrients/food groups/dietary practices, and the clinical relevance of some dietary outcomes (e.g., FV intake) was based on arbitrary cutoffs. This review focused on the key dietary factors that previous research has shown to be associated with weight gain or overweight/obesity. Other dietary factors that contribute to energy intakes but have not been shown to be associated with weight gain or overweight/obesity in population-based studies (e.g., breads and cereals, alcohol) were not considered | There is sufficient evidence that tackling dietary inequalities should be part of policy and health-promotion strategies in Europe that may also contribute to reducing socioeconomic inequalities in overweight/obesity. Targeting FV intakes may be particularly important in all regions of Europe. Public policy should ensure that socioeconomic groups have equal access and material resources to achieve a nonobesogenic diet at all stages of the life course |

| Ayala et al. (2008)15 | Consumption of fast food/snacks/added fats, whole milk, fried foods/foods prepared with lard, dairy/cheese, meat, fruit and/or vegetables, rice, beans, whole grains/bread/oats/cereal. Different measures were used: FFQs, dietary history, 24-h recalls, dietary behavior questions | Migration and acculturation: generation status, language of assessment, years in the USA, age at arrival to the USA, acculturation score | Several relationships were consistent, regardless of how acculturation was measured: 1) those who are less acculturated consume more whole milk and use more fat in food preparation, whereas the more acculturated consume more fast food, snacks, and added fats; 2) less acculturated individuals, compared with more acculturated individuals, consumed more fruit, rice, and beans; 3) less acculturated individuals consumed less sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages | No longitudinal studies. No consideration of Latino subgroups | Future studies should examine this relationship in other geographic regions of the USA and with a more socioeconomically diverse Latino population. Culturally competent care is needed. Initiatives to develop linguistically appropriate interventions and to improve the language skills of healthcare providers are needed |

| Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | FV intake. Different measures were used: FFQs, diet history, 24-h recalls, dietary behavior questions | Acculturation, anticipated regret, barriers, enabling factors, intentions, knowledge, meat preference, autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, neophobia, norms/subjective norms, outcome expectations, attitudes/beliefs, benefits, perceived need to increase FV intake, predisposing factors, preference for FV, self-efficiacy/perceived behavioral control, set example for others, social support, encouragement/influence, stages of change | Insufficient evidence of effectiveness for the following: acculturation (Mexican), meat preference, motivation–controlled, neophobia, norms/subjective norms, outcome expectations, perceived need to increase FV intake, preference for FV, set example for others. Sufficient evidence for the following: anticipated regret, barriers, enabling factors, intentions, motivation–autonomous, attitude/beliefs, benefits, predisposing factors, stages of change. Strong evidence for knowledge, self-efficacy/PBC, social support/encouragement/influence | Significant variation was observed in the outcome measure of FV intake. Limitations inherent to self-report and measurement error may under- or overestimate the assocation. Publication bias of positive findings. Heterogeneity in psychosocial constructs, quality of study designs, and measures. Inadequate analytic methods | Longitudinal studies and mediation studies are needed. Nuances in construct validity should be considered when comparing different predictors of FV intake. Future research could compare the similarities and differences in predictors of FV intake between different sociodemographic groups and could even include multilevel analyses to compare micro- and macro-level environmental and policy-related influences on FV intake. Future behavioral interventions that use strong experimental designs with efficacious constructs are needed, as are formal mediation analyses to determine the strength of these potential predictors of FV intake |

| Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Fruit consumption, vegetable consumption, FV consumption. Majority of studies used FFQs to measure dietary intake (n = 16), with the number of food items ranging from 2 (1 for fruit and 1 for vegetables) to 217 different items. Other measures that were used: 7-d food consumption diary (n = 1), 24-h recalls (n = 2). Validity of the measures was hardly discussed in the studies | Accessibility and availability, social factors, cultural factors, material factors, areas, season | Consumption of FV is likely to be higher among those with higher incomes, those who are married, those living in an advantaged neighborhood, and/or those who have good local availability and accessibility of FV | Measurements of dietary intakes and environmental determinants differed. Lack of knowledge on appropriate confounders in the relationship between the environment and FV intake. Lacks an estimation of the relative importance of environmental compared with individual-level factors. Interpretation of the results is difficult because studies in this review originated from different countries. Relevant availability-related influences may be country specific | More research into the associations between household income and FV intake is necessary to better understand the precise mechanisms. Investigate environmental influences on fruit intake and vegetable intake separately. A more specific conceptualization of cultural factors in health behavior models may be needed. Research in this area should focus on the relative importance of these factors. More research on supportive food environments is needed, ideally for different dietary intakes separately, since relevant environmental factors may differ for various outcomes. More longitudinal studies are needed. Investigate the strength of the associations observed, or study the relative importance of environmental compared with individual-level factors. A good theoretical framework should underlie research so that hypotheses can be formed and tested to further strengthen science. Extensive research into accessibility-related, availability-related, and cultural influences may result in new explanations for variations in FV consumption and offer new avenues to promote behavioral change toward recommended FV intakes |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DVD, digital video disc; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; FV, fruit and vegetable; GIS, geographic information system; PBC, perceived behavioral control; TV, television.

aThe overall results, limitations, and recommendations of the reviews reported here are those reported by the authors of the reviews themselves.

Correlate-behavior relationship: correlate and outcome measures

Potential determinants and correlates of a range of dietary behavior outcomes were explored, with many studies including multiple dietary behavior outcomes.

Of the different correlates related to a variety of healthy and unhealthy dietary behaviors, the social-cultural environmental correlates were studied most frequently (n = 8 reviews),15,16,18–21,23,25 followed by economic or financial environmental correlates (n = 4),16,19,21,22 physical environmental correlates (n = 3),16,19,21 and social-cognitive correlates (n = 3).13,20,25 Of the 4 reviews that examined economic environmental correlates, 2 focused on fruit and vegetable intake,19,21 1 focused on both healthy and unhealthy dietary behaviors,16 and 1 focused solely on unhealthy dietary behavior.22 Three reviews examined the physical environment: Kamphuis et al.21 assessed correlates of fruit and vegetable intake, whereas Caspi et al.16 and Giskes et al.19 additionally assessed correlates of snack intake. Two of the papers on social-cognitive correlates were related to fruit and vegetable intake20,25 and 1 was related to eating a “healthy diet” (operationalized by eating more fruit and fewer unhealthy snacks).13 Two systematic reviews looked at the influence of sensory correlates of fruit and vegetable intake: taste20 and preference.25 Two reviews addressed the relationship between habit strength and dietary behavior (fruit intake and snacking consumption17 and fruit and vegetable intake20). Thow et al.26 assessed the relationship between the political environment and unhealthy dietary behaviors. Six reviews addressed the relationship between other factors: sedentary behavior and both healthy and unhealthy dietary behaviors,24 sedentary behavior and fruit and vegetable intake,19 motivational regulation and fruit and vegetable intake,20,25 both social status and stress and dietary behavior,23 and shift work and snack and breakfast consumption.14

Correlates of dietary behavior most often included in the reviews were fruit intake (n = 8),13,15,17–21,24 vegetable intake (n = 6),15,19,20,21,24,25 and fruit and vegetable intake combined (n = 10).13,15,16,18–21,23–25 Eleven of the 14 reviews presented findings about the associations between correlates and fruit and/or vegetable consumption. In addition, 7 reviews also explored correlates of a variety of other dietary behaviors that were presumed as healthful (e.g., consumption of low-fat foods, healthy snacks, low-fat milk, fish, rice, beans, whole grains, breakfast,).13–16,19,23,24 Ten reviews included studies that investigated correlates of a variety of dietary behaviors regarded as unhealthful (e.g., consumption of energy-dense snacks, fast-food, take-away foods, fried foods, sweets, chocolate, desserts, sugar-sweetened beverages, whole milk, and red or processed meat).13–19,22,24,26

Importance and strength of evidence of potential determinants

Table 8 shows the importance of a correlate and its strength of evidence, based on the criteria for grading evidence as described in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The following categories of correlates were found to be significantly related to dietary behavior and/or reported a (non)significant effect size larger than 0.30 in all identified eligible studies of the included reviews that assessed these categories of correlates (++in Table 3): the political environment and unhealthy dietary behavior26; food advertisement and sugar-sweetened beverage intake22; late-shift work and low consumption of breakfast14; habit and fruit and vegetable intake17,20; behavioral regulation and fruit and vegetable intake20; sedentary behavior and fruit and vegetable intake19,24; and sedentary behavior and unhealthy dietary behavior.24 The following categories of correlates were found to be significantly related to dietary behavior and/or reported a (non)significant effect size larger than 0.30 in >75% of the identified reviews that assessed these categories of correlates (+ in Table 3): self-efficacy/perceived behavioral control,20,25 self-regulation,13 and motivation and goals20 for fruit and vegetable intake, and shift work14 and habit17 for snacking behavior. However, no conclusive evidence on the importance of specific correlates could be drawn from the reviewed reviews because the evidence found is not stronger than suggestive (Lnc or Ls in Table 8), primarily due to the cross-sectional study designs used in the large majority of studies included in the reviews.

Table 8.

Summary of the results from reviews about correlates of dietary behavior in adults: importance of a correlate and strength of evidencea

| Correlate | Dietary behavior |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating fruit | Eating vegetables | Eating fruit and vegetables | Eating snacks/fast food | Drinking sugar-sweetened beverages | Eating breakfast | |

| Physical environment | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | ||

| Giskes et al. (2011)19; Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Giskes et al. (2011)19; Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Caspi et al. (2012)16; Giskes et al. (2011)19; Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Caspi et al. (2012)16; Giskes et al. (2011)19 | |||

| Social-cultural environment | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls |

| Ayala et al. (2008)15; Giskes et al. (2010)18; Guillaumie et al. (2010)20; Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Ayala et al. (2008)15; Guillaumie et al. (2010)20; Kamphuis et al. (2006)21; Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | Ayala et al. (2008)15, Giskes et al. (2010)18, Guillaumie et al. (2010)20, Kamphuis et al. (2006)21; Moore and Cunningham (2012)23; Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | Ayala et al. (2008)15; Caspi et al. (2012)16; Giskes et al. (2011)19 | Ayala et al. (2008)15; Giskes et al. (2011)19 | Giskes et al. (2011)19; Moore and Cunningham (2012)23 | |

| Economic/financial environment | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | ++, Ls | |

| Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Caspi et al. (2012)16; Giskes et al. (2011)19; Kamphuis et al. (2006)21 | Caspi et al. (2012)16; Mills et al. (2013)22 | Mills et al. (2013)22 | ||

| Political environment | ++, Lnc | ++, Ls | ||||

| Thow et al. (2010)26 | Thow et al. (2010)26 | |||||

| Attitude | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | |||

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20; Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | ||||

| Subjective norm | 0, Ls | |||||

| Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | ||||||

| Self-efficacy/PBC | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | +, Ls | |||

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20; Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | ||||

| Intention | 0, Ls | |||||

| Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | ||||||

| Self-regulation | 0, Ls | +, Ls | 0, Ls | |||

| Adriaanse et al. (2011)13 (implementation intentions) | Adriaanse et al. (2011)13 (implementation intentions) | Adriaanse et al. (2011)13 (implementation intentions) | ||||

| Habit, automaticity | ++, Ls | ++, Lnc | ++, Ls | +, Ls | ||

| Gardner et al. (2011)17; Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Gardner et al. (2011)17 | |||

| Sensory perceptions, perceived palatability of foods | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | |||

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20; Shaikh et al. (2008)25 | ||||

| Other, knowledge | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | |||

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 | ||||

| Other, motivational regulation | 0, Ls | 0, Ls | +, Ls | |||

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 (motivation and goals) | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 (motivation and goals) | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 (motivation and goals) | ||||

| ++, Lnc | ++, Lnc | ++, Lnc | ||||

| Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 (behavioral regulation) | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 (behavioral regulation) | Guillaumie et al. (2010)20 (behavioral regulation) | ||||

| 0, Ls | ||||||

| Shaikh et al. (2008)25 (motivation: autonomous, controlled) | ||||||

| Other, sedentary behavior | ++, Ls | ++, Ls | ++, Lnc | ++, Ls | ++, Lnc | |

| Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | Giskes et al. (2011)19; Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | Pearson and Biddle (2011)24 | ||

| Other, shift work | +, Ls | ++, Ls | ||||

| Amani and Gill (2013)14 | Amani and Gill (2013)14 | |||||

Abbreviations: Co, convincing evidence; Lnc, limited, no conclusion; Ls, limited, suggestive evidence; PBC, perceived behavioral control; Pr, probable evidence.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of investigating the potential determinants of dietary behavior is to inform and guide theory and evidence-based interventions to promote healthy dietary practices, which play an important role in the prevention of noncommunicable disease. This umbrella review shows that, in particular, environmental correlates (mainly the social-cultural environment) and social-cognitive correlates have been studied quite extensively for their association with different dietary behaviors.13,15–23,25,26 Over the past decade, the social-ecological perspective appears to have gained influence, as environmental correlates have been studied most extensively during this period of time.19,21,27 This suggests that published studies have moved toward greater consideration of the social-ecological approach. This shift was also highlighted in an umbrella review of correlates of dietary behavior in youth.12 Other potential determinants of dietary behavior, such as automaticity, self-regulation, motivational regulation, and relationships with sedentary behavior, have been studied less intensively. Most reviews included in this umbrella review explored the relationship between correlates and consumption of fruit and/or vegetables. Other dietary behaviors, which varied considerably (e.g., consumption of low-fat foods, healthy snacks, breakfast, energy-dense snacks, sweets, chocolate, and sugar-sweetened beverages), were explored to a lesser extent.

The multitude of studies conducted on correlates of dietary behavior provides mixed but, in some cases, quite convincing evidence about the associations between potential determinants and a range of dietary behaviors. The political environment, self-efficacy/perceived behavior control, self-regulation, automaticity, behavioral regulation, and sedentary behavior were found to be important in explaining dietary behaviors. The limited amount of well-designed studies in this area, however, do not allow this evidence to be defined as convincing.

Social-cognitive correlates have been studied often, but the evidence on their importance is suggestive, at best. Although social-cognitive theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior6,30 have been frequently applied to explain dietary behavior and are able to explain a certain amount of variance of the behavior, they more or less presume that behavior is a rational, conscious, volitional choice.31 Fortunately, theoretical constructs that focus on habit and automaticity have received increasingly more attention, as indicated by the reviewed reviews. Habit strength was shown to be important for fruit and vegetable intake behavior as well as for snacking behavior in adults17,20; the relationship was found to be positive. Additionally, sedentary behavior was found to be consistently associated with dietary behavior.19,24 Screen time (e.g., television viewing and computer use) was positively associated with snack and sugar-sweetened beverage intake and was inversely associated with fruit and vegetable intake. Sedentary behavior and unhealthy dietary behavior may share similar environmental cues, causing these behaviors to co-occur or cluster. In addition, sedentary behavior itself may serve as a cue for consumption of energy-dense snacks. For instance, Bellisle et al.32 found that television viewing significantly stimulated food intake. Screen time is a potential factor for individuals to engage in mindless eating of larger-than-intended amounts.33

Most of the studies in the reviews were cross-sectional; thus, the evidence for true determinants remains suggestive, at best. When reflecting on the importance of correlates and the strength of evidence of associations between correlates and behavior, it is important to acknowledge the difference between well-researched (e.g., substantial amount of good-quality studies) correlates for which there is still no evidence of importance, and correlates that have just not been studied well enough to make meaningful conclusions. Hence, a reported lack of evidence of the importance of a possible determinant is not the same as evidence that the correlate is not important.

Some types or categories of correlates were not covered in the present umbrella review because no systematic reviews of such correlates that met the inclusion criteria for this review were found. For instance, various reviews on sensory correlates of dietary behavior were found, such as those of Eertmans et al.9 and Remick et al.34 Although taste and preferences are known to be crucial drivers of dietary behavior, most reviews of these topics were excluded from the present umbrella review because they focused on appetite or taste as an outcome and did not meet the quality standards of systematic reviews that were used as an inclusion criteria. In addition, new developments in the field of research on correlates of dietary behavior address factors such as impulsiveness, social-cultural influences, and environmental prompts.35–39 These factors, however, are not yet covered in systematic reviews.

Recommended steps for development of new policies and practices to change behavior

Isolated correlational approaches in which one particular type of correlate is examined in relation to dietary behavior are still dominant in the literature. This approach has helped identify the factors that may influence and determine dietary behavior as well as the possible entry points for influencing dietary behaviors. However, to understand the relationship of correlates and potential determinants with dietary behavior, an integrated ecological systems approach should be used to take the next step in operationalizing the process of interaction between environmental conditions and dietary behavior. This approach, for instance, is proposed in the EnRG framework, i.e., the framework that was also used to structure and categorize the findings of the present umbrella review. This model explicitly posits that the relationships of single categories of potential determinants can only be valuable if they are studied in their interplay – via mediating, moderating, and reciprocal relationships – with other groups of potential determinants. The EnRG approach would and should, therefore, allow for exploration and testing of mediating and moderating pathways between environmental and personal potential determinants of dietary behavior.40 Indeed, several studies combining environmental and social-cognitive variables have been reported in recent years – using the EnRG framework – and do support such mediating and moderating pathways.41–44 For instance, Tak et al.44 found that intention and habit strength partly mediated the associations between home environmental factors and soft drink consumption. Ray et al.42 found that school lunch policy moderated the relationship between family-environmental factors and vegetable intake; the association between family-environmental factors promoting fruit and vegetable intake and children’s intake of vegetables was stronger in countries that do not provide free school lunches. Research that extends beyond isolative associative approaches to a multidisciplinary, theory-based focus on environment – including, for example, behavior processes and mechanisms – is warranted.

An even better way to identify true determinants and see whether they are modifiable is to conduct experiments or quasi-experiments. These are able to test causal impact and interactions of, in general, a very limited number of potential determinants that can be manipulated in experimental settings. As valuable as this is, such studies are limited because only parts of a more comprehensive theory can be tested.45 Furthermore, larger-scale intervention studies that aim to change a broader range of potential determinants without singling these out in a full factorial model can also provide valuable information on the most relevant determinants and can inform theory by specifying the constructs that are hypothesized to affect behavior, by measuring these constructs before and after the intervention, and by identifying whether these constructs have been changed following the intervention and whether they mediate the intervention’s effect on dietary behavior change.45 Finally, prospective studies can inform theory development in situations where new behaviors have become available or where perceptions have undergone significant changes.45

Limitations and methodological issues

The studies included in the eligible reviews were prone to bias in various ways. First, the majority of the studies used cross-sectional study designs. Consequently, although such designs may be useful in identifying possible theory-based associations, drawing conclusions about directionality and possible causality of associations is not possible. Additionally, these designs can result in systematic error and an overestimation of associations among different types of correlates and dietary behaviors. More longitudinal and (quasi)-experimental study designs and intervention studies are needed to strengthen inferences. Second, studies use a large variety of approaches for conceptualizing, operationalizing, measuring, and coding the variables of interest. With regard to measurement, the validation of the measures was hardly discussed. This heterogeneity significantly limits the ability to synthesize and compare study results. Third, there is a lack of knowledge on appropriate confounders in the relationship between a particular correlate and dietary behavior. This may have resulted in overestimated associations. Fourth, studies generally fail to use quantitative dietary assessment tools such as food frequency questionnaires, repeated 24-hour recalls, and food diaries or reviews; therefore, there is a lack of reporting on the method of measurement of dietary behaviors. Finally, the systematic reviews included a wide age range of respondents 18 years and older. Most often, the reviews did not report the exact ages of the respondents. An age range of 18 years and older, without further information, is too broad to make meaningful conclusions on important correlates of dietary behaviors. After the age of 18, many life transitions take place46 that may result in differences in the importance of correlates (e.g., young adults vs elderly).47 Given these considerations, correlates of dietary behavior in specific meaningful age groups across the life course should be investigated, with an aim of providing detailed information on study populations when reporting the findings.

Umbrella reviews are subject to several limitations. Differences in reviewing methodology and reporting were observed, as were differences in, for example, categorizations of the correlates. Umbrella reviews are prone to loss of detail because quality is dependent on the reporting quality of the eligible reviews, and meta-analysis is not possible. In addition, some individual studies are included in multiple reviews, unintentionally giving them stronger weight in the results section. This umbrella review does not account for qualitative research, and reviews that addressed purchasing behavior rather than actual consumption were excluded.48 The choices one makes in the store define the availability of food products in the home environment. Finally, reviews that addressed summative outcomes (such as caloric intake) or biological correlates or determinants were not included.

CONCLUSION

This is the first umbrella review that provides an overview of reviewed research on a broad range of potential determinants of dietary behavior in adults. Social-cognitive correlates and environmental correlates were included most often in the available reviews. Environmental correlates have been studied most extensively during the past decade, indicating that published studies have moved toward greater consideration of the social-ecological approach. Sedentary behavior and habit strength were consistently identified as important correlates of dietary behavior. Other potential determinants, such as the political environment, motivational regulation, and the influence of shift work, have been examined in a few studies with promising results. However, the limited amount of well-designed studies in this area prevents this evidence from being defined as convincing. Additional systematic reviews, especially those that summarize evidence of factors that have not yet been covered in systematic reviews, are recommended. In addition, more research on so-called unhealthy behaviors is warranted, as current reviews are focused mainly on fruit and vegetable consumption. Finally, there is an ongoing need to look for new possible correlates and determinants to guide further study of the systematic development of evidence-based interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor C. de Graaf for his cooperation on this project.

Funding. This research was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, project no. 115100008.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

References

- 1.Astrup A, Dyerberg J, Selleck M, et al. Nutrition transition and its relationship to the development of obesity and related chronic diseases. Obes Rev. 2008;9(suppl 1):48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]