Abstract

Forward genetic screens are powerful tools for the discovery and functional annotation of genetic elements. Recently, the RNA-guided CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat)-associated Cas9 nuclease has been combined with genome-scale guide RNA libraries for unbiased, phenotypic screening. In this Review, we describe recent advances using Cas9 for genome-scale screens, including knockout approaches that inactivate genomic loci and strategies that modulate transcriptional activity. We discuss practical aspects of screen design, provide comparisons with RNA interference (RNAi) screening, and outline future applications and challenges.

A key goal in genetic analysis is to identify which genes contribute to specific biological phenotypes and diseases. Hypothesis-driven, reverse genetic methods take a ‘genotype-to-phenotype’ approach by using prior knowledge to test the causal role of specific genetic perturbations. By contrast, forward genetic screens are ‘phenotype-to-genotype’ approaches that involve modifying or modulating the expression of many genes, selecting for the cells or organisms with a phenotype of interest, and then characterizing the mutations that result in those phenotypic changes.

Initial forward genetic experiments carried out on model organisms such as yeast, flies, plants, zebrafish, nematodes and rodents1–9 relied on the use of chemical DNA mutagens followed by the isolation of individuals with an aberrant phenotype. These screens have uncovered many basic biological mechanisms, such as RAS and NOTCH signalling pathways10, as well as molecular mechanisms of embryonic patterning11,12 and development13,14.

A major shortcoming of DNA-mutagen-based screens is that the causal mutations in the selected clones are initially unknown. Identifying the causal mutations can be costly and labour intensive, requiring linkage analysis through crosses with characterized lines. These challenges can now be more easily addressed by mapping mutations using next-generation sequencing (NGS)15 and by replacing chemical mutagens with viruses and transposons, which use defined insertion sequences that are amenable to sequencing-based analysis16–18. An additional limitation of random mutagenesis approaches is that the resulting mutants are typically heterozygotes, which can mask recessive phenotypes. In model organisms, homozygosity can be achieved by intercrossing progeny derived from the initial heterozygous mutant. In mammalian cell culture, recessive screens have been limited to near-haploid cell lines19,20 or to cell lines that are deficient in Bloom helicase (BLM), which have an increased rate of mitotic recombination21.

Over the past decade, forward genetic screens have been revolutionized by the development of tools that use the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway for gene knockdown. RNAi is a conserved endogenous pathway in which mRNA molecules are targeted for degradation on the basis of sequence complementarity22,23, thus facilitating design and scalability of the tools. Several RNAi reagents have been developed, including long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)24, synthetic small interfering RNA (siRNA)25, short hairpin RNA (shRNA)26 and shRNAs embedded in microRNA (miRNA) precursors (shRNAmirs)27,28. Screens using RNAi tools have provided a wealth of information on gene function1,26,29–32, but their utility has been hindered by incomplete gene knockdown and extensive off-target activity, making it difficult to interpret phenotypic changes33–35.

Sequence-specific programmable nucleases have emerged as an exciting new genetic perturbation system that enables the targeted modification of the DNA sequence itself. In particular, the RNA-guided endo-nuclease Cas9 (REFS 36–41) from the microbial adaptive immune system CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat) provides a convenient system for achieving targeted mutagenesis in eukaryotic cells42,43. Cas9 is targeted to specific genomic loci via a guide RNA, which recognizes the target DNA through Watson–Crick base pairing. Therefore, Cas9 combines the permanently mutagenic nature of classical mutagens with the programmability of RNAi.

In this Review, we discuss recent Cas9-based functional genetic screening tools, including genome-wide knockout approaches and related strategies using modified forms of Cas9 to cause gene knockdown or transcriptional activation in a non-mutagenic manner44–49. We discuss how these newer approaches compare with and complement existing RNAi-based screening technologies. We also present some practical considerations for designing Cas9-based screens and potential future directions for targeted screening technology development.

Mechanisms of perturbation

Loss-of-function perturbations mediated by Cas9 and RNAi

Cas9 nuclease is a component of the type II CRISPR bacterial adaptive immune system that has recently been adapted for genome editing in many eukaryotic models (reviewed in REFS 50,51). Targeted genome engineering with Cas9 and other nucleases exploits endogenous DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair pathways to create mutations at specific locations in the genome. Although there is a large diversity of DSB repair mechanisms, genome editing in mammalian cells primarily relies on homology-directed repair (HDR), in which an exogenous DNA template can facilitate precise repair, as well as non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), which is an error-prone repair mechanism that introduces indel mutations at the repair site52. To induce DSBs, Cas9 can be targeted to specific locations in the genome by specifying a short single guide RNA (sgRNA)41 to complement the target DNA. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, the sgRNA contains a 20-bp guide sequence. The target DNA needs to contain the 20-bp target sequence followed by a 3-bp protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM), although some mismatches can be tolerated (see below).

Loss-of-function mutations mediated by Cas9 nuclease are achieved by targeting a DSB to a constitutively spliced coding exon. When a DSB is repaired by NHEJ, it can introduce an indel mutation. This frequently causes a coding frameshift, resulting in a premature stop codon and the initiation of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the transcript (FIG. 1). NMD might not be active for all genes and is not necessarily required for Cas9-mediated knockout, as an early frameshift mutation or large indels might be sufficient to produce a non-functional protein. Early exons are preferred for targeting, as indels in these exons have a higher probability of introducing an early stop codon or a frameshift of a larger portion of the protein53. As DSB induction and NHEJ-mediated repair occur independently at each allele in diploid cells, targeting by Cas9 results in a range of biallelic and heterozygous target gene lesions in different cells. We and others44–47 have used the simple, RNA-mediated programmability of Cas9 and its nuclease function to conduct genome-scale knockout screens in mammalian cell cultures. These initial screens uncovered both known and novel insights into gene essentiality and resistance to drugs and toxins. Most importantly, Cas9-based screens displayed high reagent consistency, strong phenotypic effects and high validation rates, demonstrating the promise of this approach.

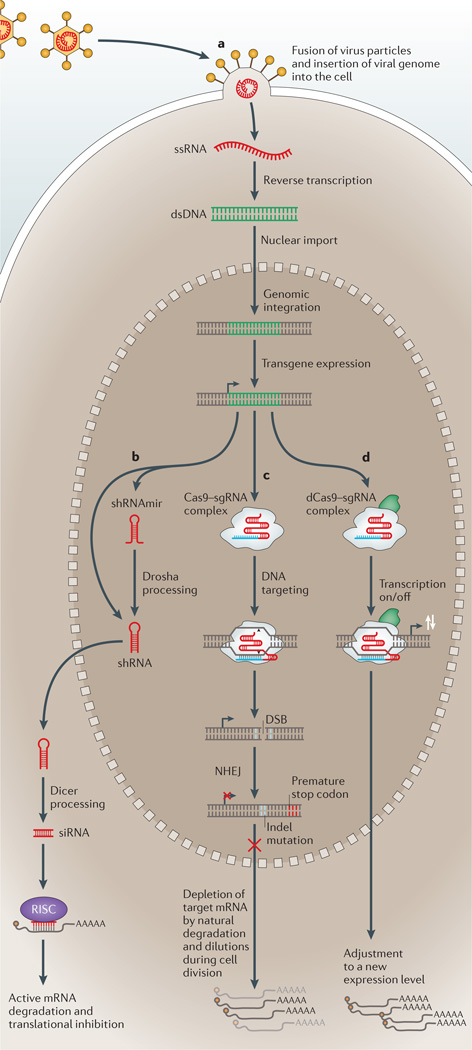

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms underlying gene perturbation via lentiviral delivery of RNA interference reagents, Cas9 nuclease and dCas9 transcriptional effectors.

a | Lentiviral transduction begins with the fusion of virus particles with the cell membrane and the insertion of the single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viral genome into the cell cytoplasm. A reverse transcriptase then converts the ssRNA genome into double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) that is imported into the nucleus and integrates into the host cell genome. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or single guide RNA (sgRNA) transgenes are then expressed from an RNA polymerase III (Pol III) or Pol II promoter. b | For shRNA transgenes, maturation involves a series of nucleolytic processing steps that result in cytoplasmic small interfering RNA (siRNA) with sequence complementarity to the target mRNA. Drosha processing is required for reagents consisting of shRNAs embedded in microRNA precursors (shRNAmirs) but is usually bypassed for simple stem–loop shRNA reagents. Gene silencing is achieved by siRNA recruitment to the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) for mRNA degradation and translational inhibition. c,d | By contrast, both the Cas9 nuclease and catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9)-mediated transcriptional modulation act in the nucleus. The transgene-encoded Cas9–sgRNA complex targets a genomic locus through sequence complementarity to the 20-bp sgRNA spacer sequence (part c). For Cas9 nuclease-mediated knockout, double-strand break (DSB) formation is followed by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) DNA repair that can introduce an indel mutation and a coding frameshift. For dCas9-mediated transcriptional modulation, the modification of expression (white arrows) depends on the exact type of fusion of either dCas9 or sgRNA (part d) (FIG. 2). These induced nuclear events, together with endogenous transcript degradation and dilution through cell division, will result in a new steady-state expression level in the cytoplasm.

Although the application of Cas9 to targeted screening is relatively recent, similar approaches based on RNAi technologies have been extensively used over the past decade in mammalian cell culture and in vivo1,3,26,29,30,54–58. RNAi is a conserved natural pathway that is triggered by various types of dsRNAs (often single-stranded RNAs folded into hairpin structures) and that results in the selective downregulation of transcripts with sequence complementarity to one strand of the dsRNA23. Natural sources of dsRNAs include endogenous mi RNAs59 and exogenous linear dsRNAs that are typically introduced into cells by invading viruses60–62. Artificial targeted gene knockdown is achieved by the delivery of a wide range of designed RNAi reagents55,63, including long dsRNAs24, siRNAs25, shRNAs26 and miRNA-embedded shRNAs27,28. The delivery of RNAi reagents is achieved by transfection of pre-synthesized RNA (for siRNAs and dsRNAs), by transfection of DNA (which encodes a promoter-driven shRNA or shRNAmir) or by viral transduction methods using lentiviral, retroviral or transposon constructs with a cloned shRNA or shRNAmir cassette (FIG. 1). In contrast to RNA polymerase III (Pol III)-driven expression of shRNAs or sgRNAs, Pol II-driven expression of shRNAmirs can be temporally controlled and genetically restricted across tissues63. Most RNAi reagents are nucleolytically processed by the enzyme Dicer into functional siRNAs. Before processing by Dicer, shRNAmirs require nuclear processing by Drosha–DGCR8, but this step is usually bypassed with other reagents63. Regardless of the reagent type, the resultant siRNAs are then loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which is guided to the target mRNA molecule by the siRNA to initiate mRNA degradation or translational inhibition23.

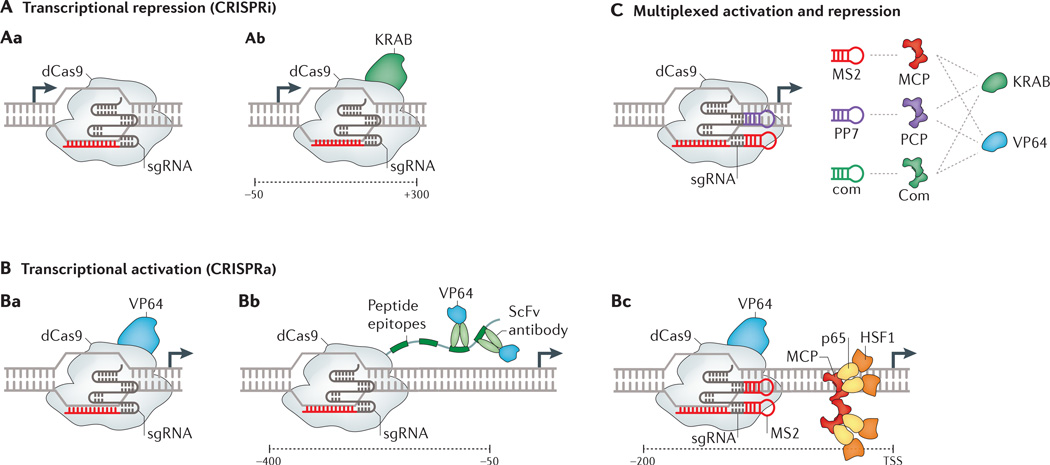

Catalytically inactive Cas9 for transcriptional modulation

In addition to gene knockout that is mediated by the error-prone repair of targeted DSBs and RNAi-based gene knockdowns, catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) and various fusions of either dCas9 or sgRNAs with transcriptional activator, repressor and recruitment domains have been used to modulate gene expression at targeted loci without introducing irreversible mutations to the genome. The dCas9-based transcriptional inhibition and activation systems are commonly referred to as CRISPRi and CRISPRa, respectively (FIG. 2). dCas9 by itself can have a repressive effect on gene expression, which is probably due to steric hindrance of the components of the transcription initiation and elongation machinery64,65 (FIG. 2Aa). Although this approach has been successful in Escherichia coli, the degree of repression achieved in mammalian cells has been modest64–68. Chromatin-modifying repressor domains have been fused to dCas9 in an attempt to improve repression in mammalian cells66 (FIG. 2Ab). However, the magnitude of repression displayed high variability across sgRNAs even with these fusion proteins66. To achieve a more robust effect, sgRNA libraries tiling the upstream regions of genes were constructed, and the variability in the measured effect on transcription was used to infer rules for the design of more-potent repressive sgRNAs48. These rules included the sgRNA target location relative to the transcription start site, the length of the protospacer and the spacer nucleotide composition features48. Although dCas9-mediated repression and RNAi-based tools seem to result in a similar molecular effect, dCas9 repression occurs by inhibiting transcription, whereas RNAi acts on the mRNAs in the cytoplasm. These differences might result in varying cellular responses.

Figure 2. dCas9-mediated transcriptional modulation.

The different ways in which catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fusions have been used to synthetically repress (CRISPRi) or activate (CRISPRa) expression are shown. All approaches use a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to direct dCas9 to a chosen genomic location. A | To achieve transcriptional repression, dCas9 can be used by itself (whereby it represses transcription through steric hindrance)64–68 (part Aa) or can be used as part of a dCas9–KRAB transcriptional repressor fusion protein48,66 (part Ab). B | For transcriptional activation, various approaches have been implemented that involve the VP64 transcriptional activator. One approach is a dCas9–VP64 fusion protein68,70–73 (part Ba). In an alternative method aimed at signal amplification, dCas9 is fused to a repeating array of peptide epitopes, which modularly recruit multiple copies of single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) antibodies fused to transcriptional activation domain48,74 (part Bb). Another approach is a dCas9–VP64 fusion protein together with a modified sgRNA scaffold with an MS2 RNA motif loop. This MS2 RNA loop recruits MS2 coat protein (MCP) fused to additional activators such as p65 and heat shock factor 1 (HSF1)49 (part Bc). C | Multiplexed activation and repression was implemented using an array of modified sgRNAs with different RNA recognition motifs (MS2, PP7 or com) and corresponding RNA-binding domains (MCP, PCP or Com) fused to different transcriptional effector domains (KRAB or VP64)76. TSS, transcriptional start site. Parts Bb and C adapted from REF. 48 and REF. 76, respectively, Cell Press; part Bc adapted from REF. 49, Nature Publishing Group.

Whereas loss-of-function screens can be conducted using a variety of both established and new Cas9-based tools, gain-of-function screens have been limited to cDNA overexpression libraries69. The coverage of such libraries is incomplete owing to the difficulty of cloning or expressing large cDNA constructs. Furthermore, these libraries often do not capture the full complexity of transcript isoforms, and they express genes independently of the endogenous regulatory context. To facilitate Cas9-based gain-of-function screens, synthetic activators were constructed by fusing dCas9 with transcriptional activation domains such as VP64 or p65 (REFS 68,70–73) (FIG. 2Ba). However, these fusions only led to modest activation when delivered with a single sgRNA in mammalian cells. The delivery of multiple sgRNAs targeting the same promoter region improved target gene activation70–72, but this was still not reliable enough to implement genome-wide activation screens. To amplify the signal of dCas9 fusion effector domains, a repeating peptide array of epitopes fused to dCas9 was developed together with activation effector domains fused to a single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) antibody74 (FIG. 2Bb). Similar to the repression screen, a tiling approach was then used to infer rules for potent sgRNAs, followed by the design of a genome-wide library and the implementation of an activation screen48.

We recently took advantage of a crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with a guide RNA and target single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)75 to rationally design an efficient Cas9 activation complex composed of a dCas9 fusion protein and modified sgRNA49 (FIG. 2Bc). This design was guided by the following principles: the use of alternative attachment positions to recruit endogenous transcription machineries more effectively; the mimicking of natural transcriptional activation mechanisms by recruiting multiple distinct activators that act in synergy to drive transcription; and the identification of design rules for efficient positioning of the Cas9 activation complex on the promoter. We used this design to implement a genome-wide gain-of-function screen49 to identify genes that confer vemurafenib resistance in melanoma cells when upregulated.

Modified scaffolds with different RNA-binding motifs were recently developed for both activation and repression of gene expression76 (FIG. 2C). A combination of these scaffolds enabled the execution of complex synthetic transcriptional programmes with the simultaneous activation and repression of different genes.

The most apparent advantage of dCas9-mediated transcriptional activation is that induction originates from the endogenous gene locus (unlike expression from an exogenous cDNA construct). Yet, the extent to which synthetic transcriptional modulators preserve the complexity of transcript isoforms and different types of feedback regulation remains to be tested77,78. In one tested case49, two transcript isoforms were expressed at equal levels, suggesting that transcript complexity can be preserved. One important advantage of cDNA expression vectors is the ability to easily express mutated genes without modifying the endogenous genomic loci.

Libraries and screening strategies

Functional screens in cultured cells are conducted in two general formats: arrayed or pooled (FIG. 3). In an arrayed format, individual reagents are arranged in multiwell plates with a single reagent (or a small pool of reagents) per well. As each reagent is separately prepared, arrayed resources are more expensive and time consuming to produce than reagents for pooled screening, and conducting arrayed screens can require special facilities that use automation for the handling of many plates. However, in arrayed screens, where each well has a single known genetic perturbation, a much wider range of cellular phenotypes can be investigated using fluorescence, luminescence and high-content imag analysis54,79–81 (FIG. 3).

Figure 3. Screening strategies in either arrayed or pooled formats.

Genetic screens follow two general formats that differ in the way in which the targeting reagents are constructed and how cell targeting and readout is carried out. a | In arrayed screens, reagents are separately synthesized and targeting constructs are arranged in multiwell plates. Cell targeting is also conducted in multiwell plates using either transfection or viral transduction. Screen readout is based on cell population measurements in individual wells. b | In pooled screens, reagents are usually synthesized and constructed as a pool. Viral transduction limits transgene copy number (ideally, one perturbation per cell), and viral integration enables readout through PCR and next-generation sequencing. Readout is based on the comparison of the abundance of the different genomically integrated transgene reagents between samples. MOI, multiplicity of infection; sgRNA, single guide RNA; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

For arrayed screens, reagents can be delivered by either transfection or viral transduction. Using transfection, a large amount of plasmid DNA encoding the RNA reagent (or pre-synthesized RNA reagent) is delivered into cells, resulting in transiently high levels of functional RNA reagents (sgRNAs, shRNAs or siRNAs) until the transfected reagents are diluted out through cell division and degradation. Using viral transduction, the multiplicity of infection (MOI) can be kept low such that most cells receive a single virus that is stably integrated. These distinct kinetics of reagent expression from transfection versus viral transduction approaches can result in differences in target specificity (discussed below).

Screening reagents in pooled formats are easier to produce owing to the availability of oligonucleotide library synthesis technologies82,83. In silico-designed libraries are synthesized as a highly complex pool of oligonucleotides. These oligonucleotides are then cloned as a pool to create a plasmid library that is used for virus production and screening26. Unlike the transfection and viral transduction options of arrayed screens, pooled screens are limited to low-MOI viral delivery. Stable transgene integration in pooled formats facilitates screen readout using NGS. This is carried out by preparing genomic DNA from the cell population, sequencing across the sgRNA-encoding or shRNA-encoding regions of the viral integrants, and then mapping each sequencing read to a pre-compiled table of the designed sgRNA or shRNA library. This results in the quantification of the relative proportion of different integrated library constructs in the cell population.

Pooled screens are less expensive and labour intensive than arrayed screens. However, both approaches still require proficiency in molecular biology, tissue culture and data analysis. It is easier to carry out screens that require long culture times in pooled formats than in arrayed formats, as the latter often use small culture volumes (for example, 384-well plates) and require special robotic equipment for passaging many plates at once. In addition, pooled approaches enable screening in in vivo environments56–58,84–86. Conversely, pooled approaches are limited to growth phenotypes (that is, effects on cell proliferation or survival) or to cell-autonomous phenotypes that are selectable by cell sorting as fluorescence or cell surface markers.

Recent Cas9–sgRNA screens44–49 in mammalian cell culture used a pooled screening approach with libraries that ranged from 103 to 105 sgRNAs. All of these libraries contained sgRNA redundancy (multiple distinct sgRNAs that target the same gene) and targeted either human or mouse genomes (TABLE 1). They all used cell growth as a phenotype and showed both positive and negative selection results.

Table 1.

Experimental parameters of recent Cas9-mediated genetic screens

| Cas9 delivery | Cas9 protein | sgRNA library size |

Number of targeted genes |

Coverage (sgRNAs per gene) |

Cell lines |

Species | Positive or negative selection |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clonal isolation of stably integrated cells |

Cas9 nuclease | 73,151 | 7,114 | 10 and tiling sgRNAs for ribosomal genes |

KBM7; HL60 |

Human | Both | 45 |

| Delivery with the sgRNA library |

Cas9 nuclease | 64,751 | 18,080 | 3 or 4 on average | A375; HUES62 |

Human | Both | 44 |

| Clonal isolation of stably integrated cells |

Cas9 nuclease | 87,897 | 19,150 | 4 on average | mESC | Mouse | Both | 46 |

| Clonal isolation of stably integrated cells |

Cas9 nuclease | 873 | 291 | 3 | HeLa | Human | Positive | 47 |

| Polyclonal selected cell Population |

dCas9 repression complex |

206,421 | 15,977 | 10 per TSS | K562 | Human | Both | 48 |

| Polyclonal selected cell Population |

dCas9 activation complex |

198,810 | 15,977 | 10 per TSS | K562 | Human | Both | 48 |

| Polyclonal selected cell Population |

dCas9 activation complex |

70,290 | 23,430 | 3 per TSS | A375 | Human | Both | 49 |

dCas9, catalytically inactive Cas9; mESC, mouse embryonic stem cell; sgRNA, single guide RNA; TSS, transcription start site.

In positive selection screens, a strong selective pressure is introduced such that there is only a low probability that cells without a relevant survival-enhancing perturbation will remain following selection. Commonly, positive selection experiments are designed to identify perturbations that confer resistance to a drug, toxin or pathogen. One example is a screen for host genes that are essential for the intoxication of cells by anthrax toxin47. In this case, most sgRNAs are depleted owing to the strong selective pressure of the toxin, and only a small number of cells, which are transduced with sgRNAs that introduce a protective mutation, survive and proliferate. As very few hits are usually expected and resistant cells continue to proliferate, the signal is strong and easy to detect in pooled approaches.

In negative selection, the goal is to identify perturbations that cause cells to be depleted during selection; such perturbations typically affect genes that are necessary for survival under the chosen selective pressure. The simplest negative selection screen is continued growth for an extended period of time: in this case, the depleted cells are those carrying reagents that target genes that are essential for cell proliferation. These genes can be found by comparing the relative frequency of each sgRNA between a late time point and an earlier one. Negative selection screens almost always require greater sensitivity to changes in the representation of library reagents, as the depletion level is more modest and the number of depleted genes is larger (for example, essential genes). Moreover, when using Cas9 nuclease, there is a chance that not all mutations will abolish gene function owing to small in-frame mutations, resulting in a mixed phenotype. One important application of negative selection screens is the identification of gene perturbations that selectively target cancer cells which harbour known oncogenic mutations; these ‘oncogene addictions’ might serve as possible drug targets87,88.

Target specificity

Target specificity is an important point of consideration for all gene perturbation systems (TABLE 2). It consists of the ratio between on-target efficacy and unintended off-target effects, which is manifested by the consistency between unique reagents that target the same gene. On-target efficacy is a measure of how well a reagent can modify the expression of its intended gene target. Off-target effects include the perturbation of unintended genetic elements and global cellular responses. Target specificity will depend on the exact experimental settings. For example, as the concentrations of Cas9 and sgRNA affect target specificity89, transient transfections will differ from low-MOI transductions in target specificity.

Table 2.

Features of the different perturbation tools used for targeted genetic screens

| Loss of function |

Gain of function |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 nuclease | CRISPRi | RNAi tools | CRISPRa | cDNA overexpression |

|

|

Type of perturbation |

Indel mutation in the target DNA that generally results in a complete knockout owing to a coding frameshift |

Repression of gene expression by dCas9-mediated transcriptional inhibition |

Repression of gene expression by targeting the mRNA molecule for degradation and translational inhibition |

Activation of gene expression by dCas9-mediated recruitment of transcriptional activation domains to TSSs |

Exogenous overexpression of cloned cDNA constructs |

|

Expected off-target effects |

Additional unexpected indels in the genome |

Repression of additional genes and effects on chromatin |

Repression of additional mRNAs owing to partial ‘seed’ matching and imprecise Dicer processing; global effects owing to saturation of endogenous RNAi machinery (mostly relevant to siRNA transfections) |

Expression of additional genes and effects on chromatin |

Not many gene-specific off-target effects; global effects on translation owing to strong expression of a single gene |

|

On-target efficacy |

With continuous expression, near-complete allelic modification can be achieved in a short time frame |

Inhibition level depends on the choice of sgRNA and the basal expression level of the target gene |

Repression efficacy depends on the choice of RNAi tool and the specific targeting sequence |

Activation level depends on the choice of sgRNA and the basal expression level of the target gene |

High expression of most cDNA constructs owing to expression from the same promoter |

|

Constitutive versus conditional expression |

Cas9 expression can be made conditional |

Cas9 expression can be made conditional |

Only Pol II-driven RNAi reagents can be conditionally expressed |

Cas9 expression can be made conditional |

cDNA constructs can be conditionally expressed |

|

Reversibility of perturbation |

Irreversible | Reversible | Reversible | Reversible | Reversible |

| Refs | 44–47 | 48 | 1 | 48,49 | 69 |

dCas9, catalytically inactive Cas9; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; RNAi, RNA interference; sgRNA, single guide RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TSS, transcription start site.

Gene targeting reagent consistency

One of the encouraging results observed in the initial Cas9-mediated knockout screens44–47 was that, for the top-scoring genes, a high percentage of unique sgRNAs designed to target the same genes were enriched following positive selection. One example is a screen carried out to identify gene knockouts that confer resistance to the chemotherapy etoposide45. As DNA topoisomerase 2A (TOP2A) creates cytotoxic DSBs during treatment with etoposide, TOP2A depletion results in drug resistance. Impressively, all ten distinct sgRNAs for the TOP2A gene showed high levels of enrichment in drug-treated samples. This level of consistency is rarely observed in RNAi-based screens, resulting in the generation of very large, high-coverage RNAi reagent libraries90. We have observed similar results44, in which a high percentage of sgRNAs for the top-scoring gene hits showed a strong phenotypic effect in a screen for resistance to the RAF inhibitor vemurafenib. We directly compared these results with a previous vemurafenib resistance screen using RNAi (shRNA)91. Interestingly, we found that the top ten hits of both screens (based on RIGER92 analysis) shared only a single gene and that reagent consistency was much higher for the hits in the Cas9 screen (78% versus 20% of reagents enriched). In another study that aimed to identify genes involved in susceptibility to 6-thioguanine (6-TG) and susceptibility to Clostridium septicum α-toxin in mouse embryonic stem cells46, both known and novel hits were found. Similarly, a higher percentage of sgRNAs were able to produce a phenotype than in shRNA knockdown when validated using individual sgRNAs for the top hits. In our positive selection vemurafenib screen, we also found a high validation rate with six of seven of the top hits reproducing the pooled screen results in arrayed-format drug titration curves44. Although these results are promising, more side-by-side comparisons with RNAi-based screens using different phenotypes and established RNAi screening platforms and libraries55,93 are needed. In addition, the main results to be emphasized by the recent Cas9-knockout screens have been obtained using strong positive selection pressure. There is still a need for more-extensive validation and comparison to RNAi tools using negative selection experiments.

Despite the high consistency in strong positive selection screens, sgRNAs can still have large variations in efficiencies. This difference can be partially predicted by sgRNA sequence features45,53 and chromatin accessibility at the target site94, and can be used in the design of more-efficient libraries53. Although it is tempting to infer quantitative phenotypic information from growth-based Cas9-knockout genetic screens (for example, assigning fitness measures to gene knockouts), it is important to realize that quantitative differences in depletion or enrichment of the sgRNA-encoding constructs might result from differences in sgRNA efficiencies that cause earlier or later knockouts.

Achieving high levels of reagent consistency for dCas9-based transcriptional modulation is more challenging, as the effect of different sgRNAs will be affected by the relative distance to the transcription start site in a manner that might differ between genes. For both repression and activation, library design was guided by the unbiased testing of sets of sgRNAs48,49. Reassuringly, using a similar RAF inhibition positive selection experiment, we observed high levels of consistency between unique activating sgRNAs49.

On-target loss of function and reagent efficacy

Continuous expression of the Cas9 nuclease using low-MOI lentiviral transduction can result in near-complete allelic modification owing to the irreversibility of the genomic modification44,46,47, as long as no transgene silencing occurs. However, error-prone DSB repair will result in different mutations in different cells, and there is no guarantee that every mutation will abolish gene function. For example, small in-frame indels might not disrupt gene function. Given that every cell usually has more than one gene copy, this will result in a multimodal distribution that consists of defined null, hetero-zygote and wild-type expression states (FIG. 4a). This is in contrast to RNAi and dCas9 reagents that modulate transcription, which are expected to have similar effects across transduced cells, resulting in a general shift in the continuous expression distribution (FIG. 4b). This difference will not be apparent from mean expression measurements in bulk cell populations. It is worth noting that, in practice, we and others have observed an almost complete level of gene knockout at the protein level44,46 for a limited set of tested proteins. This can be explained by additional repressive effects of Cas9 binding by steric hindrance, large in-frame deletions that still abolish gene function or a higher sensitivity to mutations at these loci. Interestingly, the distribution of indel sizes can vary between targeted loci44–46,95,96 and can be partially predicted by the DSB flanking sequences95, suggesting that modifications at different loci will result in different percentages of disruptive mutations and that such information can be incorporated in future libraries to achieve higher knockout efficacy.

Figure 4. Distinct expression distributions for knockdown and knockout of a gene.

a | Theoretical target gene expression distribution following knockout mediated by lentiviral-delivered Cas9 nuclease is shown. This assumes an 80% level of allelic mutations that abolish gene function, combining out-of-frame and large deletions, close to complete allele modification rate and diploid cells. Although most cells will have a complete knockout in both alleles, some cells will retain at least one copy of a functional allele. b | Theoretical target gene expression distribution following catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9)-mediated transcriptional repression or RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown is shown. All transduced cells experience a similar perturbation that results in a shift in the target gene expression distribution.

Direct comparison of the phenotypes following Cas9 versus shRNA targeting demonstrated stronger effects of Cas9 in a few tested cases. This was shown both in pooled formats for dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression48 and in arrayed validation44,46 for the Cas9 nuclease. This suggests a greater efficacy of individual sgRNAs than shRNA in these cases. An advantage of using Cas9 nuclease over transcriptional modulation approaches is that mutations are irreversible and are not affected by subsequent transgene silencing. However, in RNAi, it is easier to monitor and isolate cells that harbour the intended expression perturbation. This can be achieved by co-delivery of the RNAi reagent and a reporter but, when using Cas9, sgRNA expression does not indicate the duration and magnitude of the actual genetic perturbation.

Off-target activity

Characterizing off-target effects and enhancing the specificity of both Cas9 and RNAi reagents continue to be major challenges for improving both research and clinical applications.

For Cas9-mediated genome editing, early reports demonstrated that Cas9 tolerates mismatches between the sgRNA and the target sequence across the whole recognition site in a manner that depends on the mismatch positions, number of mismatches and nucleotide identity73,89,97–99. In our design of genome-wide libraries, we used early empirical mismatch data89 to choose sgRNAs with minimal predicted off-target activity100. Much work is still required in order to fully characterize Cas9 off-target effects. For example, recent work has suggested that small insertions or deletions (‘bulges’ in the sgRNA or DNA target) can also be tolerated99.

Unbiased methods to detect Cas9-induced DSBs and Cas9-binding events are providing a more refined picture of where Cas9 binds and induces unintended modifications. Initial attempts to map off-target genome modifications using whole-genome sequencing revealed a low incidence of off-target modifications101,102. However, this approach is limited by sequencing coverage to detect low-frequency events. Recently, unbiased detection of DSBs103,104 revealed unexpected off-target activity that could not have been predicted using the current computational tools. Additional experiments using such unbiased methods will provide a better understanding of Cas9 target specificity. Another unbiased approach is mapping of dCas9 binding using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by NGS (ChIP–seq)94,105. Such studies revealed a surprisingly large number of off-target binding events mediated by short PAM-proximal homology between the guide RNA and target sequence. Reassuringly, when this off-target binding occurs for catalytically active Cas9 it is not typically sufficient to induce DSBs, probably because the transient binding and imperfect matching of sgRNA to the target sequence is insufficient for DNA cleavage106. This raises concern that transcriptional modulation screens might be affected by this high incidence of transient off-target binding. However, dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression was shown to be sensitive to even a few mismatches48, and genome-wide expression profiling exhibited specific effects for both activation and repression48,66. Moreover, large control sets of sgRNAs did not show any phenotypic off-target effects for both activation and repression of transcription48. For future library designs, specificity could be further improved using sgRNA modifications107,108, double-nicking approaches73,109, synthetic Cas9 protein design with improved specificity75,110 and the use of different Cas9 orthologues111,112.

For RNAi-based screening strategies, the characterization and avoidance of off-target effects have been subject to extensive investigation in recent years33,35,113,114. Early gene expression profiling studies revealed that unique siRNA reagents targeting the same genes displayed siRNA sequence-driven effects rather than signatures of target gene modulation, hinting at low target specificity35. This was later realized to occur as processed siRNAs enter the natural miRNA pathways that target transcripts with 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) sequences that have complementarity to the 5′ region of the siRNA34. Targeting can occur even when only eight nucleotides of the siRNA match, an effect that is similar to the ‘seed region’ in miRNA targeting. Recently, seed effects alone were used to identify host factors that are required for the infection of human cells by various different pathogens115. Although these reports were based on the transfection of large amounts of synthetic siRNA, gene silencing using different RNAi reagents, such as low-MOI transductions of shRNA or shRNAmir, would not necessarily be prone to the same level of off-target effects. Ongoing efforts to design algorithms for the more accurate prediction of targets of both endogenous miRNAs and exogenous RNAi triggers can improve both the design of RNAi reagent libraries and data analysis116. Finally, advances in the mechanistic understanding of miRNA biogenesis117,118 can facilitate improved design of RNAi reagents and expression vectors that will avoid imprecise Dicer processing and produce higher levels of functional siRNAs.

To summarize, although off-target effects are a major concern for both Cas9 and RNAi approaches, they depend on the exact experimental settings and can be minimized by better mechanistic understanding and refinement of the currently used tools. Off-target effects are a major concern in clinical applications: when attempting to correct a disease-associated gene in a patient, a rare off-target mutation could potentially be toxic or oncogenic. By contrast, in genetic screens, false-positive hits owing to off-target perturbations can be easily avoided by requiring that multiple distinct reagents targeting the same genetic element display the same phenotype.

Practical considerations

Many of the technical details for conducting a genome-scale screen using Cas9 are similar to RNAi screens. These have been extensively discussed in other reviews3,26,30,55; thus, we focus here on topics that are specific to the use of Cas9.

Cas9 delivery

The most commonly used Cas9 protein, from the bacterium S. pyogenes, is a large protein that is encoded by a 4.1-kb coding sequence. This suggests two delivery approaches for Cas9-mediated genetic screens. The first involves the delivery of only Cas9 (viral integration or knock-ins) to generate a stable Cas9-expressing, clonal or polyclonal cell line, followed by cell expansion and the delivery of an sgRNA-only library. Clonal cell lines have the advantage that a line with high Cas9 expression levels can first be selected. However, generating a clonal cell line is not necessarily possible for all cell lines, and cells can accumulate mutations during expansion from a single cell. The second approach comprises simultaneous delivery of both Cas9 and sgRNAs using library vectors that encode both components. Although the first approach can be easily applied in immortalized cell lines, it is less feasible in primary cells that are not easily expanded in culture. For the second approach, delivery of both Cas9 and sgRNA in a single virus is challenging because viral titres can be low owing to the size of the cas9 gene. We have recently improved the titre of the single virus system100, thus enabling easier screening applications in primary cells or cells that are difficult to transduce. An additional option is to use a cas9-transgenic mouse119, which circumvents the need for Cas9 delivery for in vivo or mouse-derived primary-cell screening applications.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors have advantages for in vivo and gene therapy applications, as they do not integrate into the genome and are thus less likely to induce oncogenesis. For pooled screening applications, the non-integrating nature of AAV vectors is less favourable because genomic integration is used to read out the abundance of the different perturbation reagents in a heterogeneous population of selected cells. However, AAV-based pooled screens might have advantages in certain in vivo applications: for non-dividing cells, the viral episome can be used for NGS readout. As the combined size of S. pyogenes Cas9 and the sgRNA cassette is already near the packaging limit of AAV, efficient in vivo editing by Cas9 AAV delivery requires either the delivery of two separate AAV vectors120 or a single vector system using a smaller Cas9 orthologue from the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, which we have recently adapted for in vivo genome editing111.

Culture time before selection for efficient targeting

Success of Cas9 nuclease knockout screens requires a high genomic modification rate with a culture time that will suffice to deplete most of the proteins. Measurements of allelic modification rates in the first published screens demonstrated close to complete allelic modification after approximately 10 days across several gene targets44–47. There is no guarantee that all cell lines will display similar results, and it is important to measure allelic modification rates as a function of time across several genomic loci before using a cell line for screening.

Additional time needs to be added for the depletion of perturbed proteins. In contrast to RNAi that acts directly on the mRNA by actively degrading it, both Cas9 nuclease and dCas9-mediated protein depletion modulate transcription in the nucleus. This is combined with endogenous mRNA degradation and dilution owing to cell proliferation, and results in a slower change in mRNA levels (FIG. 1). This difference might be small in rapidly dividing cells, but depleting stable proteins in post-mitotic or even slowly dividing cells can require longer culture times post-transduction. The mode of delivery can also have an effect on the required time for gene perturbation. For example, arrayed format transfection of synthetic siRNA libraries121 results in faster knockdown than lentiviral transduction, which requires subsequent transgene expression and nucleolytic processing to generate mature siRNAs.

Interaction with cellular machinery

The dependence on endogenous cellular pathways can introduce limitations when designing a perturbation screen. RNAi-based tools depend on an active endogenous RNAi pathway, whereas Cas9 tools act by exogenous delivery of all components (with the exception of endogenous NHEJ mechanisms, which are required for indel formation in knockout screens but which are not needed thereafter). The RNAi pathway has been associated with a wide variety of cellular processes ranging from host–pathogen interactions and cellular differentiation, to cancer122. Additionally, genes that are directly involved in RNAi activity cannot be continuously targeted efficiently using synthetic RNAi reagents; therefore, they may be missed if they are involved in the screened phenotypes. dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression screens can serve as a good alternative for knockdown screens in these cases, as this type of silencing is expected to use fewer endogenous pathways (FIG. 2), thus reducing the chance of having disruptive interactions between the targeted genetic element and the targeting tool.

An additional concern is the global effect of the targeting reagents on cellular physiology. The delivery of large amounts of exogenous siRNAs might saturate the endogenous RNAi system, resulting in additional toxic effects33. Although this is a major concern in arrayed siRNA transfection experiments, it might be less relevant to low-MOI viral-based shRNA or shRNAmir delivery. Cas9 expression in cells, and the external induction of DSBs, has not been studied in depth, and more work is still needed to establish that there are no disruptive or toxic effects.

Challenges and future outlook

Initial Cas9-mediated screens displayed remarkable results, with high levels of guide consistency, genomic modification, hit confirmation and strong phenotypic effects44–49. Despite these promising results, there are many aspects of using Cas9 for functional genomics that require further study. These include investigation into the cellular response to Cas9 delivery and activity in cells, and the demonstration of the same high levels of sgRNA consistency across a wider range of cell models and phenotypes. There is also a need for the unbiased estimation of false-negative rates, as it is not clear how many of the sgRNA reagents in a particular computationally designed library actually perturb the intended targets. Although the high consistency of hit sgRNAs per gene suggests that this percentage is quite high, there is still a need for an unbiased test across multiple genomic locations. In addition, negative selection screens for growth phenotypes remain a challenge, which might be addressed by improving the efficiency of sgRNAs53, developing more-sensitive screen readout methods and improving the statistical analysis tools.

Knockout, knockdown and activation screens are complementary methods (TABLE 2) that together will contribute to a more complete understanding of biological systems. For example, genes that retain function at low expression levels will be unlikely to display an obvious phenotype upon knockdown and might therefore be missed in knockdown screens. By contrast, genes that are essential for cell viability cannot be assessed for their contribution to additional cellular phenotypes using complete knockout; partial knockdown will be useful in these cases. In addition, as gene regulatory networks are highly inter connected and contain multiple feedback loops, the cellular phenotype in response to knockout and knockdown can be markedly different.

Screening opportunities using Cas9 extend beyond coding genes. Custom-designed sgRNA libraries can be used for the unbiased discovery of regulatory sequences by tiling sgRNAs throughout a non-coding genomic region. The delivery of multiple sgRNAs42,72,123 can facilitate screening for epistatic effects between pairs of genes124 or can be used to induce more-disruptive genetic modifications such as microdeletions. It is also possible to study the effects of perturbing non-coding RNAs. In this case, nuclease-induced DSBs might be suboptimal, as translational frameshift and NMD are less relevant. Instead, deletion approaches using two sgRNAs, or effective dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression, might be more suitable. In addition, fusing Cas9 to additional effector domains can facilitate high-throughput screens for phenotypic effects of additional epigenetic modifications68. Another type of high-throughput assay used Cas9 combined with HDR to conduct saturation mutagenesis experiments within an endogenous locus, thus expanding the possibilities of studying sequence-encoded regulatory information125.

NGS has revolutionized our ability to read information from the genome, including the DNA sequence itself, the state of the transcriptome and the epi-genome126,127. With these new insights into the genome, there is a need to understand the function of genetic elements through perturbation. Cas9-mediated screens will have an important role in drawing causal links between genetic architecture and phenotypes, and will enhance our ability to decipher cellular function in health and disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank L. Solomon for help with illustrations, J. Wright for manuscript review and members of the Zhang Laboratory for discussions. O.S. is supported by a Klarman Family Foundation Fellowship. N.E.S. is supported by a Simons Center for the Social Brain Postdoctoral Fellowship and by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) of the US National Institutes of Health under award number K99-HG008171. F.Z. is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (DP1-MH100706), the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (R01-NS07312401), a US National Science Foundation (NSF) Waterman Award, the Keck, Damon Runyon, Searle Scholars, Klingenstein, Vallee, Merkin, Simons, and New York Stem Cell Foundations, and Bob Metcalfe. F.Z. is a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator.

Glossary

- Small interfering RNA

(siRNA). RNA molecules that are 21–23 nucleotides long and that are processed from long double-stranded RNAs;. they are functional components of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). siRNAs typically target and silence mRNAs by binding perfectly complementary sequences in the mRNA and causing their degradation and/or translational inhibition.

- Short hairpin RNA

(shRNA). Small RNAs forming hairpins that can induce sequence-specific silencing in mammalian cells through RNA interference, both when expressed endogenously and when produced exogenously and transfected into the cell.

- microRNA

(miRNA). Small RNA molecules processed from hairpin-containing RNA precursors that are produced from endogenous miRNA-encoding genes. mi RNAs are 21–23 nucleotides in length and, through the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), they target and silence mRNAs containing imperfectly complementary sequences.

- Indel

(Insertion and deletion). Mutations due to small insertions or deletions of DNA sequences.

- Single guide RNA

(sgRNA). An artificial fusion of CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat) RNA (crRNA) and transactivating crRNA (tracrRNA) with critical secondary structures for loading onto Cas9 for genome editing. It functionally substitutes the complex of crRNA and tracrRNA that occurs in natural CRISPR systems. It uses RNA–DNA hybridization to guide Cas9 to the genomic target.

- Nonsense-mediated decay

(NMD). An mRNA surveillance mechanism that degrades mRNAs containing nonsense mutations to prevent the expression of truncated or erroneous proteins.

- CRISPRi

An engineered transcriptional silencing complex based on catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fusions and/or single guide RNA (sgRNA) modification.

- CRISPRa

An engineered transcriptional activation complex based on catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fusions and/or single guide RNA (sgRNA) modification.

- False-positive

Pertaining to screening results: in a screen that results in a set of putative gene hits associated with a phenotype, a false positive is a gene that is predicted to be associated but that is actually not associated with the phenotype.

- False-negative

Pertaining to screening results: in a screen that results in a set of putative gene hits associated with a phenotype, a false negative is a true hit that was missed.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing interests: see Web version for details.

References

- 1.Boutros M, Ahringer J. The art and design of genetic screens: RNA interference. Nature Rev. Genet. 2008;9:554–566. doi: 10.1038/nrg2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kile BT, Hilton DJ. The art and design of genetic screens: mouse. Nature Rev. Genet. 2005;6:557–567. doi: 10.1038/nrg1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimm S. The art and design of genetic screens: mammalian culture cells. Nature Rev. Genet. 2004;5:179–189. doi: 10.1038/nrg1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorgensen EM, Mango SE. The art and design of genetic screens: Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature Rev. Genet. 2002;3:356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.St Johnston D. The art and design of genetic screens: Drosophila melanogaster. Nature Rev. Genet. 2002;3:176–188. doi: 10.1038/nrg751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patton EE, Zon LI. The art and design of genetic screens: zebrafish. Nature Rev. Genet. 2001;2:956–966. doi: 10.1038/35103567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forsburg SL. The art and design of genetic screens: yeast. Nature Rev. Genet. 2001;2:659–668. doi: 10.1038/35088500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page DR, Grossniklaus U. The art and design of genetic screens: Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Rev. Genet. 2002;3:124–136. doi: 10.1038/nrg730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuman HA, Silhavy TJ. The art and design of genetic screens: Escherichia coli. Nature Rev. Genet. 2003;4:419–431. doi: 10.1038/nrg1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundaram MV. The love-hate relationship between Ras and Notch. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1825–1839. doi: 10.1101/gad.1330605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nüsslein-Volhard C, Frohnhöfer HG, Lehmann R. Determination of anteroposterior polarity in Drosophila. Science. 1987;238:1675–1681. doi: 10.1126/science.3686007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nüsslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287:795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driever W, et al. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:37–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haffter P, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 1996;123:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneeberger K. Using next-generation sequencing to isolate mutant genes from forward genetic screens. Nature Rev. Genet. 2014;15:662–676. doi: 10.1038/nrg3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Harnessing transposons for cancer gene discovery. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:696–706. doi: 10.1038/nrc2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupuy AJ, Akagi K, Largaespada DA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Mammalian mutagenesis using a highly mobile somatic Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Nature. 2005;436:221–226. doi: 10.1038/nature03691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rad R, et al. PiggyBac transposon mutagenesis: a tool for cancer gene discovery in mice. Science. 2010;330:1104–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.1193004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotecki M, Reddy PS, Cochran BH. Isolation and characterization of a near-haploid human cell line. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;252:273–280. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carette JE, et al. Haploid genetic screens in human cells identify host factors used by pathogens. Science. 2009;326:1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1178955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo G, Wang W, Bradley A. Mismatch repair genes identified using genetic screens in Blm-deficient embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2004;429:891–895. doi: 10.1038/nature02653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fire A, et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. This paper reports the discovery of RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans

- 23.Ketting RF. The many faces of RNAi. Dev. Cell. 2011;20:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meister G, Tuschl T. Mechanisms of gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature. 2004;431:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature02873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McManus MT, Sharp PA. Gene silencing in mammals by small interfering RNAs. Nature Rev. Genet. 2002;3:737–747. doi: 10.1038/nrg908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Root DE, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM. Genome-scale loss-of-function screening with a lentiviral RNAi library. Nature Methods. 2006;3:715–719. doi: 10.1038/nmeth924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva JM, et al. Second-generation shRNA libraries covering the mouse and human genomes. Nature Genet. 2005;37:1281–1288. doi: 10.1038/ng1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang K, Elledge SJ, Hannon GJ. Lessons from nature: microRNA-based shRNA libraries. Nature Methods. 2006;3:707–714. doi: 10.1038/nmeth923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paddison PJ, et al. A resource for large-scale RNA-interference-based screens in mammals. Nature. 2004;428:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature02370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moffat J, Sabatini DM. Building mammalian signalling pathways with RNAi screens. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berns K, et al. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature. 2004;428:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nature02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boutros M, et al. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of growth and viability in Drosophila cells. Science. 2004;303:832–835. doi: 10.1126/science.1091266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birmingham A, et al. 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nature Methods. 2006;3:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nmeth854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson AL, et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nature Biotech. 2003;21:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology. 2005;151:2551–2561. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garneau JE, et al. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 2010;468:67–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09523. This paper reports that Cas9 facilitates the cleavage of target DNA in bacterial cells

- 38.Deltcheva E, et al. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature. 2011;471:602–607. doi: 10.1038/nature09886. This paper reports that processing of CRISPR RNA is facilitated by small non-coding transactivating crRNA (tracrRNA

- 39.Sapranauskas R, et al. The Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR/Cas system provides immunity in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9275–9282. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr606. This paper reports that the Cas9 system is modular and can be transplanted into distant bacterial species to target plasmid DNA

- 40.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E2579–E2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. This paper, along with reference 40, characterizes Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage in vitro. This paper also shows that Cas9 can cleave DNA in vitro using chimeric sgRNAs containing a truncated tracrRNA.

- 42.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. References 42 and 43 describe the successful harnessing of Cas9 for genome editing

- 44.Shalem O, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang T, Wei JJ, Sabatini DM, Lander ES. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science. 2014;343:80–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1246981.References 44 and 45 describe the development of lentiviral genome-scale sgRNA libraries and the application for positive and negative selection genetic screening in human cells

- 46.Koike-Yusa H, Li Y, Tan E-P, Velasco-Herrera MDC, Yusa K. Genome-wide recessive genetic screening in mammalian cells with a lentiviral CRISPR-guide RNA library. Nature Biotech. 2014;32:267–273. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2800.This paper describes the development of lentiviral genome-scale sgRNA libraries and the application for positive and negative selection genetic screening in mouse cells

- 47.Zhou Y, et al. High-throughput screening of a CRISPR/ Cas9 library for functional genomics in human cells. Nature. 2014;509:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature13166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilbert LA, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell. 2014;159:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029. This paper describes the development and application of lentiviral genome-scale dCas9-mediated gene activation and repression for gain-of-function and loss-of-function screening

- 49.Konermann S, et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2015;517:583–588. doi: 10.1038/nature14136. This paper describes structure-guided engineering of a robust Cas9-based transcriptional activator and the development of a genome-scale sgRNA library for gain-of-function genetic screening

- 50.Kim H, Kim J-S. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nature Rev. Genet. 2014;15:321–334. doi: 10.1038/nrg3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:8096–8106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doench JG, et al. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nature Biotech. 2014;32:1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Echeverri CJ, Perrimon N. High-throughput RNAi screening in cultured cells: a user’s guide. Nature Rev. Genet. 2006;7:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrg1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohr SE, Smith JA, Shamu CE, Neumüller RA, Perrimon N. RNAi screening comes of age: improved techniques and complementary approaches. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schramek D, et al. Direct in vivo RNAi screen unveils myosin IIa as a tumor suppressor of squamous cell carcinomas. Science. 2014;343:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1248627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beronja S, et al. RNAi screens in mice identify physiological regulators of oncogenic growth. Nature. 2013;501:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou P, et al. In vivo discovery of immunotherapy targets in the tumour microenvironment. Nature. 2014;506:52–57. doi: 10.1038/nature12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nature Rev. Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maillard PV, et al. Antiviral RNA interference in mammalian cells. Science. 2013;342:235–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1241930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Y, Lu J, Han Y, Fan X, Ding S-W. RNA interference functions as an antiviral immunity mechanism in mammals. Science. 2013;342:231–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1241911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burgess DJ. Small RNAs: antiviral RNAi in mammals. Nature Rev. Genet. 2013;14:821. doi: 10.1038/nrg3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan Q, van der Laan LJW, Janssen HLA, Peppelenbosch MP. A dynamic perspective of RNAi library development. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qi LS, et al. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larson MH, et al. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nature Protoc. 2013;8:2180–2196. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gilbert LA, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bikard D, et al. Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7429–7437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Konermann S, et al. Optical control of mammalian endogenous transcription and epigenetic states. Nature. 2013;500:472–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang X, et al. A public genome-scale lentiviral expression library of human ORFs. Nature Methods. 2011;8:659–661. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maeder ML, et al. CRISPR RNA-guided activation of endogenous human genes. Nature Methods. 2013;10:977–979. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perez-Pinera P, et al. RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nature Methods. 2013;10:973–976. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng AW, et al. Multiplexed activation of endogenous genes by CRISPR-on, an RNA-guided transcriptional activator system. Cell Res. 2013;23:1163–1171. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mali P, et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nature Biotech. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tanenbaum ME, Gilbert LA, Qi LS, Weissman JS, Vale RD. A protein-tagging system for signal amplification in gene expression and fluorescence imaging. Cell. 2014;159:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nishimasu H, et al. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell. 2014;156:935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zalatan JG, et al. Engineering complex synthetic transcriptional programs with CRISPR RNA scaffolds. Cell. 2015;160:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bregman A, et al. Promoter elements regulate cytoplasmic mRNA decay. Cell. 2011;147:1473–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trcek T, Larson DR, Moldón A, Query CC, Singer RH. Single-molecule mRNA decay measurements reveal promoter-regulated mRNA stability in yeast. Cell. 2011;147:1484–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hasson SA, et al. High-content genome-wide RNAi screens identify regulators of parkin upstream of mitophagy. Nature. 2013;504:291–295. doi: 10.1038/nature12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moffat J, et al. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Neumann B, et al. High-throughput RNAi screening by time-lapse imaging of live human cells. Nature Methods. 2006;3:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nmeth876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.LeProust EM, et al. Synthesis of high-quality libraries of long (150mer) oligonucleotides by a novel depurination controlled process. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2522–2540. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cleary MA, et al. Production of complex nucleic acid libraries using highly parallel in situ oligonucleotide synthesis. Nature Methods. 2004;1:241–248. doi: 10.1038/nmeth724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malina A, et al. Repurposing CRISPR/Cas9 for in situ functional assays. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2602–2614. doi: 10.1101/gad.227132.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zender L, et al. An oncogenomics-based in vivo RNAi screen identifies tumor suppressors in liver cancer. Cell. 2008;135:852–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rudalska R, et al. In vivo RNAi screening identifies a mechanism of sorafenib resistance in liver cancer. Nature Med. 2014;20:1138–1146. doi: 10.1038/nm.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheung HW, et al. Systematic investigation of genetic vulnerabilities across cancer cell lines reveals lineage-specific dependencies in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12372–12377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109363108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whitehurst AW, et al. Synthetic lethal screen identification of chemosensitizer loci in cancer cells. Nature. 2007;446:815–819. doi: 10.1038/nature05697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hsu PD, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nature Biotech. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bassik MC, et al. Rapid creation and quantitative monitoring of high coverage shRNA libraries. Nature Methods. 2009;6:443–445. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Whittaker SR, et al. A genome-scale RNA interference screen implicates NF1 loss in resistance to RAF inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:350–362. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Birmingham A, et al. Statistical methods for analysis of high-throughput RNA interference screens. Nature Methods. 2009;6:569–575. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoffman GR, et al. Functional epigenetics approach identifies BRM/SMARCA2 as a critical synthetic lethal target in BRG1-deficient cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:3128–3133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316793111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu X, et al. Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nature Biotech. 2014;32:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bae S, Kweon J, Kim HS, Kim J-S. Microhomology-based choice of Cas9 nuclease target sites. Nature Methods. 2014;11:705–706. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hendel A, et al. Quantifying genome-editing outcomes at endogenous loci with SMRT sequencing. Cell Rep. 2014;7:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pattanayak V, et al. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nature Biotech. 2013;31:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fu Y, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nature Biotech. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7473–7485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nature Methods. 2014;11:783–784. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Veres A, et al. Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN-based genome editing in human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:12–13. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Frock RL, et al. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nature Biotech. 2015;33:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tsai SQ, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nature Biotech. 2015;33:187–197. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, Thorpe J, Adli M. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature Biotech. 2014;32:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, Doudna JA. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature. 2014;507:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen B, et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell. 2013;155:1479–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, Joung JK. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nature Biotech. 2014;32:279–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ran FA, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jinek M, et al. Structures of Cas9 endonucleases reveal RNA-mediated conformational activation. Science. 2014;343:1247997. doi: 10.1126/science.1247997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ran FA, et al. In vivo genome editing with Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Esvelt KM, et al. Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nature Methods. 2013;10:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Qiu S, Adema CM, Lane T. A computational study of off-target effects of RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1834–1847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Buehler E, et al. siRNA off-target effects in genome-wide screens identify signaling pathway members. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:428. doi: 10.1038/srep00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]