Abstract

Methods

An international database of 1499 laparoscopic liver resections was analysed using multivariate and Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results

In total, 764 stapler hepatectomies (SH) were compared with 735 electrosurgical resections (ER). SH was employed in larger tumours (4.5 versus 3.8 cm; P < 0.003) with decreased operative times (2.6 versus 3.1 h; P < 0.001), blood loss (100 versus 200 cc; P < 0.001) and length of stay (3.0 versus 7.0 days; P < 0.001). SH incurred a trend towards higher complications (16% versus 13%; P = 0.057) including bile leaks (26/764, 3.4% versus 16/735, 2.2%: P = 0.091). To address group homogeneity, a subset analysis of lobar resections confirmed the benefits of SH. Kaplan–Meier analysis in non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic patients confirmed equivalent patient (P = 0.290 and 0.118) and disease-free survival (P = 0.120 and 0.268). Multivariate analysis confirmed the parenchymal transection technique did not increase the risk of cancer recurrence, whereas tumour size, the presence of cirrhosis and concomitant operations did.

Conclusions

A SH provides several advantages including: diminished blood loss, transfusion requirements and shorter operative times. In spite of the smaller surgical margins in the SH group, equivalent recurrence and survival rates were observed when matched for parenchyma and extent of resection.

Introduction

After five decades of innovation, a hepatic resection has become an accepted surgical procedure for the management of both benign and malignant tumours. Significant conceptual and technical changes have resulted in a dramatic improvement in patient survival. These changes included improved understanding of intrahepatic vascular and biliary anatomy, the use of hypovolemic fluid management, selective vascular control, the introduction of the laparoscopic approach and varied forms of hepatic parenchymal division. A stapler hepatectomy (SH) is one of these parenchymal dissection techniques that have found new utility in the expansion of a laparoscopic liver resection.1–3 This technique was first described by Nagorney et al. over 20 years ago.4 Buchler et al. subsequently popularized this technique in an open liver resection.5,6

Initial descriptions of a laparoscopic liver resection came from European centres.7–9 These reports were limited to peripheral resections, and came with warnings of significant complications and requirements of expertise in laparoscopic as well as hepatobiliary surgery. Several early adopters of laparoscopic liver surgery pursued a SH as an alternative to clip directed dissection. A stapled right hepatectomy was first reported by O'Rourke et al. and was thought to be a safer alternative technique for parenchymal dissection.10 Subsequently, several high volume groups adopted this technique. This study serves to evaluate the benefits and weaknesses of SH across a multi-institutional series of groups utilizing electrosurgery and SH for parenchymal dissection.

Methods

After institutional review board approval for a computerized, multi-institutional retrospective cohort study, de-identified data were merged into a central database and examined. An international database of 1499 laparoscopic liver resections was established and patient outcomes were analysed using univariate, and multivariate analysis. A 10 centre international cohort of laparoscopic liver resections was assembled. Two laparoscopic cohorts were created: the first cohort was constructed of centres performing a laparoscopic SH and the second cohort was comprised of centres performing an electrosurgical hepatectomy. The method of parenchymal transection was up to the surgeon's preference; patients entered in this study had their surgery either performed at centres using the stapler or an electrosurgical technique. Both techniques have been well described previously.11–13 An electrosurgical resection (ER) included radiofrequency ablation, tissuelink, ligasure and ultrasonic dissection while for simplicity any patients that underwent pre-ablation followed by a stapled parenchymal transection were excluded. The Pringle manoeuvre was routinely employed in the electrosurgical group but not within the SH group. Stapled vascular inflow and/or outflow control was permitted in the electrosurgical group as long as staplers were not utilized for parenchymal transection.

Demographic data, pre-operative diagnoses, symptoms, intra-operative data, patient outcomes and tumour characteristics were examined. All data are presented as median with ranges. Patients were analysed on an intent-to-treat basis based on the parenchymal transection technique. Comparisons were performed between the SH and the electrosurgical hepatectomy group. Continuous covariates were analysed using the Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, where appropriate. Categorical variables were analysed by the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate. A univariate analysis was performed to examine the homogeneity of the two resectional groups. Further analysis was performed to evaluate the surgical outcomes of each technique. Analyses included multivariate analysis, chi-square, Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney test as indicated. To adjust for malignant disease, the size of the resection and the incidence of cirrhosis several subset analyses were performed. Subset analysis was limited to major lobar resections defined as either formal lobectomies or a trisegmentectomy. Lobar resection data from the SH and ER group were analysed on the basis of the patients' underlying parenchyma: cirrhotic versus non-cirrhotic. To assess the oncological integrity of SH compared with the electrosurgical approach; Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed for patient and disease-free survival for all patients with cancer, with additional subset analysis performed between the cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients. A P-value of 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Cost analysis was performed for SH and ER. Owing to the international basis of this study, cultural variation is considerable and this could account for dramatic differences in the length of stay data. As a result of this confounding variable, it was elected to perform only an operative cost analysis. This was performed using cost data for disposable devices and calculated anaesthesia and operative room cost per unit time ($158 US dollars/minute) with the primary authors' expense data used as an index cost. In the SH group, the primary author's institutional price was used for the stapler handles, disposable load, tissuelink, ligasure, an ultrasonic dissector and hand assist devices; when used this expense was calculated as the disposable expense.

Results

Analysis of an international database comprised of 1499 laparoscopic liver resections identified 764 (51%) SH and 735 (49%) ER. Patient demographics, tumour characteristics, intra-operative and post-operative outcomes are presented and analysed for all patients in Table 1. The incidence of post-operative liver failure was equivalent between the SH and ER groups (7/764; 0.9% versus 7/735; 1.0%; P = 0.942). The most common complications in the SH and ER group were biliary (26/764; 3.4% versus 16/735; 2.2%; P = 0.153), pulmonary (20/764;2.6% versus 13/735; 1.8%; P = 0.262), abdominal fluid collections (8/764; 1.0% versus 8/735; 1.1%; P = 0.937), liver failure (8/764; 1.0% versus 7/735; 1.0%; P = 0.853), post-operative ileus (14/764; 1.8% versus 8/735; 1.1%; P = 0.231), ascites (4/764; 0.5% versus 16/735; 2.2%; P = 0.005), post-operative hernia (12/764; 1.6% versus 6/735; 0.8%; P = 0.187), post-operative bleed (8/764; 1.0% versus 4/735; 0.5%; P = 0.274), chronic pain (8/764; 1.0% versus 6/735; 0.8%; P = 0.642) and other (14/764; 1.8% versus 12/735; 1.6%; P = 0.767).

Table 1.

Demographic, operative and outcome comparison of a stapler and electrosurgical hepatic resection

| Stapler hepatectomy | Electrosurgical resection | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 55.0 (18–88) | 58.0 (18–91) | 0.019 |

| Female incidence | 459/764 (60%) | 390/735 (53%) | 0.002 |

| Median ASA | 2.0 (1–4) | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.423 |

| Median BMI | 27.0 (17–33) | 23.8 (19–47) | 0.001 |

| Cancer incidence | 383/764 (37.1%) | 378/735 (51.5%) | 0.003 |

| Cirrhosis incidence | 112/764 (14.6%) | 242/735 (33%) | 0.001 |

| Median tumour size (cm) | 4.5 (0.5–50) | 3.8 (0.5–25) | 0.003 |

| Incidence of lobar resection | 107/764 (14%) | 162/735 (22%) | 0.001 |

| Incidence of repeat resections | 11/764 (1.4%) | 9/735 (1.2%) | 0.883 |

| Median OR time (h) | 2.6 (0.5–12.7) | 3.1 (0.5–7.0) | 0.001 |

| Median EBL (ml) | 100.0 (50–10,000) | 200.0 (0–1500) | 0.006 |

| Incidence of transfusions | 39/764 (5.1%) | 65/735 (8.9%) | 0.004 |

| Incidence of conversion | 12/764 (1.6%) | 16/735 (2.2%) | 0.432 |

| Incidence of complications | 121/764 (15.9%) | 92/735 (12.6%) | 0.067 |

| Median length of stay (days) | 3.0 (1–154) | 7.0 (1–160) | 0.003 |

| Median margins (cm) | 1.0 (0–9) | 1.0 (0.1–6) | 0.003 |

| Overall incidence of tumour recurrence | 81/764 (10.6%) | 134/735 (18.3%) | 0.001 |

BMI, body mass index

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification

EBL, estimated blood loss

OR, operating room

LOS, length of stay

R1, resection resulting in a microscopic positive margin.

All contnuous variables are presented as medians with ranges.

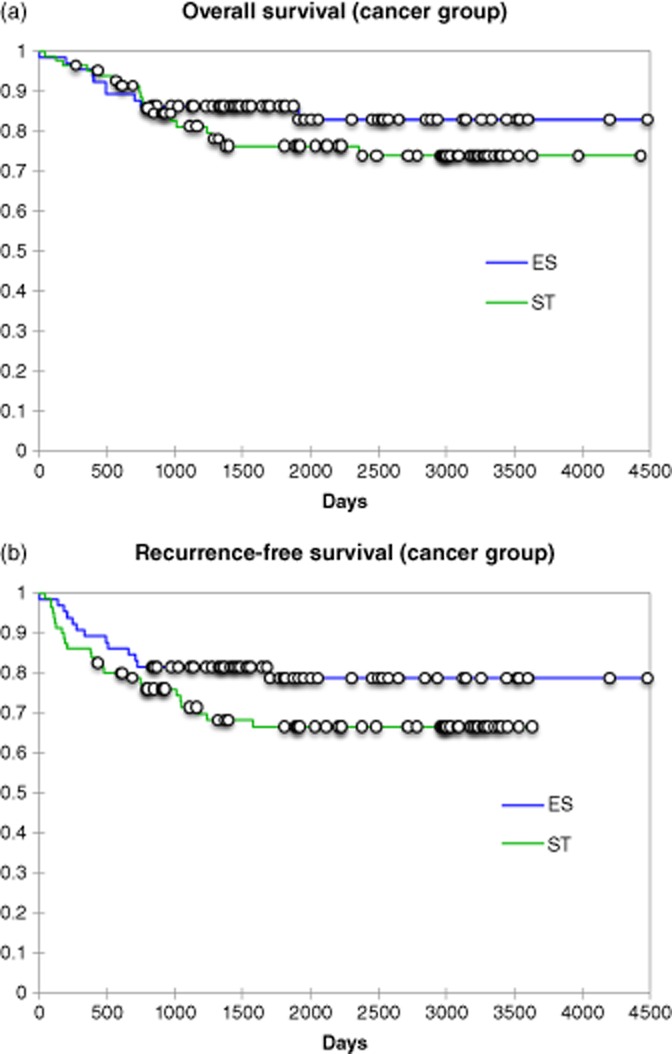

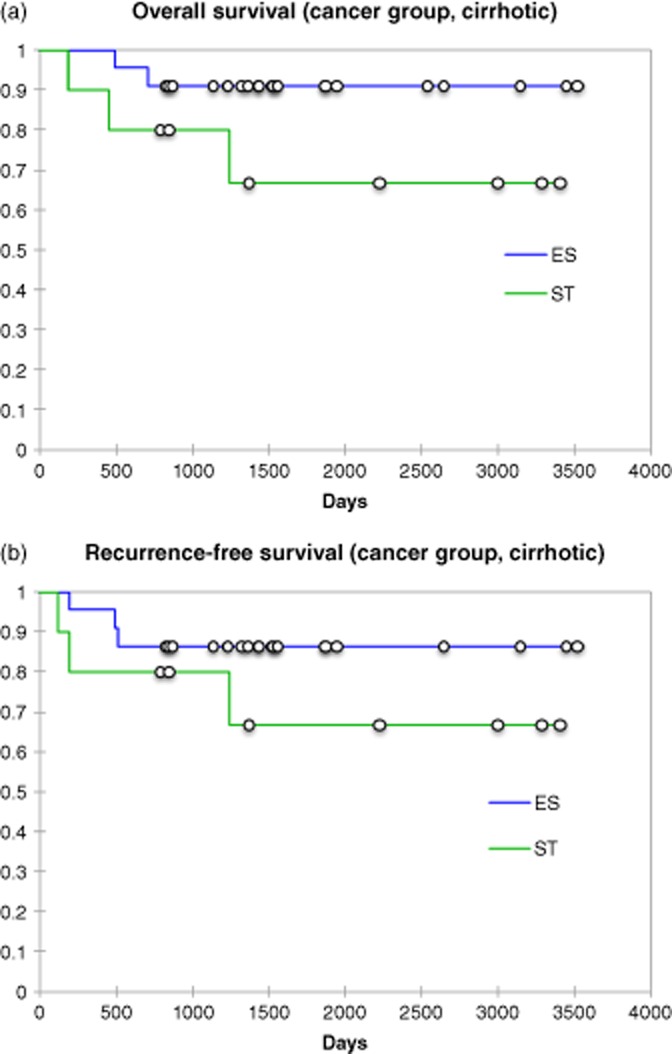

The non-cirrhotic group lobar resection group comprised of 269 (18%) patients with 165 (61%) being performed with SH and 104 (39%) ER. Forty (3%) cirrhotic patients undergoing lobar resections were also examined with 26 being SH and 14 ER. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 2. These data confirm when the extent of a resection is controlled. SH continues to demonstrate advantages in decreased operative time, lower blood loss and shorter hospital stay. Similar findings were present in the cirrhotic group with the exception of shorter length of stay. Further analysis of data did identify SH had a smaller pathological margin on explanation than an electrosurgical dissection. The incidence of recurrence between the SH and ER groups were not significantly different (21/81:25.9% versus 11/65: 16.9%; P < 0.191). The median (range) time to recurrence was 13.0 (3–36) versus 13.1 (5–55) months after a similar median follow-up period of all patients [62.8 (13–106) months versus 54.5 (5–55) months]. The most common site of cancer recurrence in the lobar resections between the SH and ER were a second liver site (10/21 versus 8/11; P = 0.173), lung (5/21 versus 2/11; P = 0.714), carcinomatosis (3/21 versus 1/11; P = 0.673) and the resection margin (2/21 versus 1/11; P = 0.968). To assess the oncological integrity of SH to ER all patients with cancer undergoing a major lobar resection were compared using a Kaplan–Meier analysis to examine the overall survival and disease-free survival (Figs 1, 2). No difference in either overall patient survival or disease-free survival was identified. A multivariate analysis was then performed in all cancer patients that required lobar or greater resections (Table 3). This analysis identified smaller tumours as a continuous variable were at a lower risk for recurrence, whereas the presence of larger tumours, cirrhosis or the need for concomitant intra-abdominal surgery were at the highest risk for tumour recurrence.

Table 2.

Comparison of stapler (SH) and electrosurgical resection (ER) in equivalent sized lobar resections

| Non-cirrhotic lobectomies | Cirrhotic lobectomies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | SH | P-value | ER | SH | P-value | |

| No. of patients | 104 | 165 | 26 | 14 | ||

| Median BMI | 23.5 (18–31) | 28.0 (14–43) | 0.001 | 23.6 (21–38) | 29.0 (23–29) | 0.091 |

| Median ASA | 2.0 (2–3) | 3.0 (1–4) | 0.593 | 2.0 (1–4) | 3.0 (2–4) | 0.922 |

| Median age (years) | 55.7 (18–83) | 54.0 (18–91) | 0.812 | 59.0 (35–78) | 62.0 (41–87) | 0.223 |

| Incidence cancers | 43/104 (41%) | 71/165 (43%) | 0.836 | 22/26 | 10/14 | 0.762 |

| Median tumour size (cm) | 6.5 (0.7–6.0) | 7.0 (0.8–21) | 0.752 | 4.7 (1–12) | 5.5 (1–8) | 0.873 |

| Median EBL (ml) | 400 (50–10,000) | 150 (25–3000) | 0.001 | 462 (100–3500) | 150 (25–500) | 0.023 |

| Median OR time (min) | 5.0 (2.7–12.0) | 3.0 (0.5–12.2) | 0.001 | 5.2 (3–9.1) | 2.2 (1–5.8) | 0.001 |

| Incidence of transfusion | 7/104 (7%) | 15/165 (9%) | 0.474 | 1/26 | 1/14 | 0.145 |

| Median LOS (days) | 8.0 (1–60) | 3.0 (1–11) | 0.0001 | 10.5 (6–30) | 7.0 (2–8) | 0.498 |

| Incidence of complications | 26/104 (25%) | 36/165 (22)% | 0.255 | 8/26 | 6/14 | 0.563 |

| Median margin (cm) | 1.5 (0–6) | 1.0 (0–6.0) | 0.062 | 1.8 (0.1–9.0) | 2 (0.5–2.0) | 0.753 |

| Incidence of R1 resection | 2/43 | 2/71 (2.9%) | 0.988 | 0/22 | 0/10 | 1.000 |

| 90-day mortality | 1/104 (1.0%) | 2/165 (1.2%) | 0.976 | 0/26 | 0/14 | 1.000 |

| Incidence of cancer recurrence | 8/43 | 18/71 (25%) | 0.323 | 3/22 | 3/10 | 0.755 |

BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; EBL, estimated blood loss; OR, operating room; LOS, length of stay; R1, resection resulting in a microscopic positive margin.

Figure 1.

(a) Overall patient survival for non-cirrhotic cancer patients undergoing a lobar resection; P-log-rank = 0.29. (b) Overall disease-free survival for non-cirrhotic cancer patients undergoing a lobar resection; P-log rank = 0.118

Figure 2.

(a) Overall patient survival for cirrhotic cancer patients undergoing a lobar resection; P-log rank = 0.12. (b) Overall disease-free survival for cirrhotic cancer patients undergoing a lobar resection; P-log rank = 0.268

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting cancer recurrence

| Variable | Hazard ratio | Hazard ratio 95% confidence levels | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour size | 0.965 | 0.935 | 0.997 | 0.033 |

| Absence of cirrhosis | 0.561 | 0.316 | 0.997 | 0.049 |

| Transfusion | 0.540 | 0.311 | 0.936 | 0.028 |

| Concomitant surgery | 1.350 | 0.730 | 2.496 | 0.339 |

The median disposable expense differential between SH and ER was $3200 per patient; however, SH reduced the median operative room utilization by 0.5 h (cost of $158/minute) for a median cost savings of $4740. When all the operative time savings were subtracted from the disposable expenses the total operative cost with SH resulted in $13 000 per patient cost savings.

Discussion

A hepatic resection has evolved over the past four decades from a significantly morbid and often fatal operation, to a routine surgical procedure with reported mortality rates of less than 5%, performed for both benign and malignant tumours of the liver.14–16 This dramatic change was achieved through improved knowledge of intrahepatic vascular and biliary anatomy, and the introduction of new surgical and anaesthetic techniques. A SH was first introduced over 20 years ago as a novel technique for division of vascular inflow and outflow pedicles.1–5 This technique was subsequently modified to an ultrasound-guided intrahepatic portal triad division to minimize dissection at the portal bifurcation. A SH was frequently discussed but found little support in the general hepatobiliary literature until the introduction of laparoscopic liver resection.13

Multiple studies have confirmed intra-operative blood loss and post-operative transfusion requirements were predictors of post-operative morbidity and mortality in liver surgery. Additional data suggested transfusion requirements impacted the oncological outcomes of a hepatic resection for colorectal metastases and hepatocellular cancer.17–19 Data from this study demonstrates in this multi-institutional study that SH results in significantly shorter operative times, with less blood loss and lower transfusion requirements. These clinical outcomes confirmed the findings of two prior studies performed by Schemmer et al. and Reddy et al.5,6,20 To insure the validity of these observations, subset analysis of only lobar resections confirmed SH resulted in shorter operative times and lower blood loss. Oncologic data for cancer lobectomies confirmed patient and disease survival were equivalent between SH and ER. Seemingly in spite of smaller surgical margins, SH resulted in equivalent oncological outcomes. With early recognition of the importance of haemorrhage control, several techniques for vascular control have been employed and studied. The most commonly employed technique for vascular control of the liver is intermittent inflow control, known as the Pringle manoeuver. Intermittent inflow control is easy to perform but has the challenge of time limitations and the risk of significant remnant ischaemia and subsequent reperfusion injury. Two other methods of vascular control for liver resection have been employed: total vascular isolation (TVI) and selective vascular isolation. TVI was first reported by the Mt. Sinai transplant group where upper and lower caval control, as well as aortic and portal inflow is employed. This technique proved effective, but is difficult to perform and is seldom used in current liver surgery. The alternative technique was selective vascular isolation whose concept is appealing, providing haemorrhage control without the risk of remnant ischaemia or subsequent reperfusion injury. This technique was first described and employed by Longmire using the clamp bearing his name. In a retrospective study performed by Buell et al., selective vascular control was shown to provide superior outcomes to TVI and the Pringle manoeuver.21

A laparoscopic SH was the natural progression of selective vascular control. The stapler employs haemorrhage control without incurring remnant ischaemia. This study examines the use of SH in the setting of a multi-institutional experience with a laparoscopic liver resection. However, present data suggests there is a bias in the use of SH. Importantly is the recognition that SH is more commonly employed in the United States. With this recognized, and the cultural reality of Asian and European centres, there is a clear expectation that ER employed by the same centres would result in a significantly longer hospital stay. Reddy et al. similar to the current series experienced with SH identified this technique was more frequently employed in female patients, patients with benign tumors, and in the setting of non-cirrhotic livers.20 Interestingly, this present study supports that, unlike previously reported series, SH is utilized for larger tumours, and more frequently for major hepatectomies than ER.21–28 In spite of what might be perceived as more complex resections, the mean operative times, blood loss and transfusion requirements remained less than that of the ER group. Conversion to open surgical procedures was similar in both the SH and ER groups. SH patients did experience a trend towards a higher incidence of post-operative complications, including bile leak, than in the ER group. The bile leak rate in this series was less than that previously reported by Schemmer et al. or Reddy et al. of 8% and 12%, respectively.5,6,20

Lastly, the oncological integrity of this technique must be addressed. SH provides a smaller pathological margin than the electrosurgical technique. In spite of this finding, neither a Kaplan–Meier analysis nor a multivariate regression analysis identified SH as a risk factor for tumour recurrence. This would suggest that this pathological margin may not reflect an actual margin. SH requires significant compression of the liver parenchyma and destruction of surrounding hepatic tissue. This mechanical compression may in fact result in tissue destruction, falsely altering the pathological margin. In spite of the salutary benefits of SH, several significant shortfalls exist. The first is the existence of a significant learning curve associated with the use of the two principle stapling devices and development of a decision algorithm for the amount and type of tissue placed into the stapler. Each stapler has several important mechanical characteristics including the staple formation mechanism, aperture gap and the necessary compression pressures. Inappropriate attempts at vascular division can led to immediate or delayed staple line disruption. Staple disruption of the hepatic or portal vein can result in a massive haemorrhage with the risk of an air embolism. In spite of this risk of stapler disruption, if SH is carried out in a correct manner the incidence of these events are rare. The second shortfall is the cost of SH. Significant criticism has been has been focused on this fact. Analysis of cost data shows the cost of staplers and a hand assist device in our cohort was $3200. When cost was adjusted for a reduction in utilized operating room time, the operative cost confirmed a $13 000 savings. Analysis of hospitalization cost was felt to be inappropriate because of the significant cultural variations in hospitalization expectations.

SH appears to provide several significant intra-operative advantages over ES including a shorter operative time and diminished blood loss. SH when used correctly has a similar safety and efficacy profile to ES. Concerns over smaller resection margins appear to be unfounded, but warrant further investigation. Cost analysis appears to find disparaging comments over cost unwarranted. This study supports SH as a safe and efficacious technique, but notes surgeons should employ the technique with which they are most comfortable.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Lefor AT, Flowers JL. Laparoscopic wedge biopsy of the liver. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:307–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefor AT, Flowers JL, Heyman MR. Laparoscopic staging of Hodgkin's disease. Surg Oncol. 1993;2:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Useful stapling techniques in liver surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEntee GP, Nagorney DM. Use of vascular staplers in major hepatic resections. Br J Surg. 1991;78:40–41. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schemmer P, Bruns H, Weitz J, Schmidt J, Büchler MW. Liver transection using vascular stapler: a review. HPB. 2008;10:249–252. doi: 10.1080/13651820802166930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schemmer P, Friess H, Dervenis C, Schmidt J, Weitz J, Uhl W, et al. The use of endo-GIA vascular staplers in liver surgery and their potential benefit: a review. Dig Surg. 2007;24:300–305. doi: 10.1159/000103662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherqui D, Husson E, Hammoud R, Malassagne B, Stéphan F, Bensaid S, et al. Laparoscopic liver resections: a feasibility study in 30 patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:753–762. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Champault A, Dagher I, Vons C, Franco D. Laroscopic hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Retrospective study of 12 patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:969–973. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)88169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belli G, Fantini C, D'Agostino A, Belli A, Langella S. Laparoscopic hepatic resection for completely exophytic hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:488–493. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Rourke N, Fielding G. Laparoscopic right hepatectomy: surgical technique. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:213–216. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gayet B, Cavaliere D, Vibert E, Perniceni T, Levard H, Denet C, et al. Total laparoscopic right hepatectomy. Am J Surg. 2007;194:685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagher I, Caillard C, Proske JM, Carloni A, Lainas P, Franco D. Laparoscopic right hepatectomy: origional techniques and results. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:756–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buell JF, Thomas M, Doty T, Merchen TD, Gupta M, Gersin K, et al. Initial experiences and evolution in laparoscopic hepatic resection. Surgery. 2004;136:804–811. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster JH. Survival after liver resection for cancer. Cancer. 1970;26:493–502. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197009)26:3<493::aid-cncr2820260302>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiu MH, Fortner JG. Current management of hepatic tumors. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortner JG, Shiu MH, Kinne DW, Kim DK, Castro EB, Watson RC, et al. Major hepatic resection using vascular isolation and hypothermic perfusion. Ann Surg. 1974;180:644–652. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197410000-00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooby DA, Stockman J, Ben-Porat L, et al. Influence of transfusions on perioperative and long-term outcome in patients following hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2003;237:860–870. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000072371.95588.DA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen CB, Nagorney DM, Taswell HF, Helgeson SL, Ilstrup DM. Heerden JA, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and determinants of survival after liver resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 1992;216:493–505. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199210000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Linehan D. Use of a bipolar vessel-sealing device for parenchymal transection during liver surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:569–574. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy SK, Barbas AS, Gan TJ, Hill SE, Roche AM, Clary BM. Hepatic parenchymal transection with vascular staplers: a comparative analysis with the crush-clamp technique. Am J Surg. 2008;196:760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buell JF, Koffron A, Hanaway M, Lo A, Yoshida A, Layman R, et al. Longmire, Pringle, total vascular isolation: is any method of vascular control superior in hepatic resection of metastatic cancers? Arch Surg. 2001;136:569–575. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delis SG, Bakoyiannis A, Karakaxas D, Athanassiou K, Tassopoulos N, Manesis E, et al. Hepatic parenchyma resection using stapling devices: peri-operative and long-term outcome. HPB. 2009;11:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter S, Kollmar O, Schuld J, Moussavian MR, Igna D, Schilling MK Chirurgische Arbeitsgemeinschaft OP-Technik und OP-Strukturen (CAOP) of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie. Randomized clinical trial of efficacy and costs of three dissection devices in liver resection. Br J Surg. 2009;96:593–601. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gumbs AA, Gayet B, Gagner M. Laparoscopic liver resection: when to use the laparoscopic stapler device. HPB. 2008;10:296–303. doi: 10.1080/13651820802166773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saidi RF, Ahad A, Escobar R, Nalbantoglu I, Adsay V, Jacobs MJ. Comparison between staple and vessel sealing device for parynchemal transection in laparoscopic liver surgery in a swine model. HPB. 2007;9:440–443. doi: 10.1080/13651820701658219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balaa FK, Gamblin TC, Tsung A, Marsh JW, Geller DA. Right hepatic lobectomy using the staple technique in 101 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:338–343. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buell JF, Marvin M, Nagubandi R, Ravindra K, McMasters KM, Thomas MT, et al. Experience with more than 500 minimally invasive hepatic procedures. Ann Surg. 2009;249:1065–1066. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185e647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buell JF, Cherqui D, Geller DA, O'Rourke N, Iannitti D, Dagher I, et al. The international position on laparoscopic liver surgery: the Louisville statement 2008. Ann Surg. 2009;250:825–830. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181b3b2d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]