Abstract

Aim

We explored how acculturation and self-actualization affect depression in the HIV-positive Asians and Pacific Islanders immigrant population.

Background

Asians and Pacific Islanders are among the fastest growing minority groups in the US. Asians and Pacific Islanders are the only racial/ethnic group to show a significant increase in HIV diagnosis rate.

Design

A mixed-methods study was conducted.

Methods

Thirty in-depth interviews were conducted with HIV-positive Asians and Pacific Islanders in San Francisco and New York. Additionally, cross-sectional audio computer-assisted self-interviews were conducted with a sample of 50 HIV-positive Asians and Pacific Islanders. Content analysis was used to analyze the in-depth interviews. Also, descriptive, bivariate statistics and multivariable regression analysis was used to estimate the associations among depression, acculturation and self-actualization. The study took place from January - June 2013.

Discussion

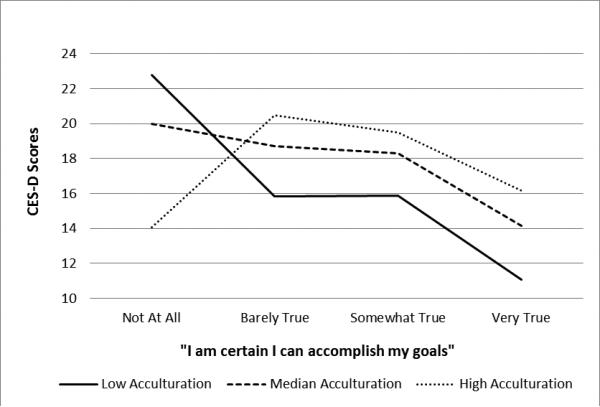

Major themes were extracted from the interview data, including self-actualization, acculturation and depression. The participants were then divided into three acculturation levels correlating to their varying levels of self-actualization. For those with low acculturation, there was a large discrepancy in the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale scores between those who had totally lost their self-actualization and those who believed they could still achieve their ‘American dreams’. Among those who were less acculturated, there was a significant difference in depression scores between those who felt they had totally lost their ability to self-actualize and those who still believed they could ‘make their dreams come true.’

Conclusion

Acculturation levels influence depression and self-actualization in the HIV-positive Asians and Pacific Islanders population. Lower-acculturated Asian Americans achieved a lower degree of self-actualization and suffered from depression. Future interventions should focus on enhancing acculturation and reducing depression to achieve self-actualization.

Keywords: Nursing, depression, stress, acculturation, American dream, self-actualization, HIV, Asian, immigrants

INTRODUCTION

The United States is a host country to immigrants and refugees from around the world. From 2000 to 2008, immigration accounted for 36% of the total population increase in the United States, representing more than 8 million immigrants. The states with the largest number of new immigrants during this period were California, New York, Texas and Florida (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). According to the most recent U.S. census, Asian and Pacific Islanders (API) represent 6% of the total United States population (or close to 18.5 million) including the multi-ethnic and multi-racial Asian population (Applied Research Center and the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA), 2013). Following the Immigration Act of 1965, API migrated to the USA in a series of large waves. Currently, the majority of Asian Americans (67.4%) are foreign-born, compared with only 29.2% of Latinos (Leong et al. 2013).

Immigrants and HIV are not often studied in relation to each other, but in fact, between immigration policy, disease prevention and HIV treatment, many HIV-specific difficulties are encountered by immigrant populations. According to U.S. immigration law prior to 2010, HIV-positive individuals were not eligible to legally immigrate to the USA. Until the HIV ban was removed in 2010, people who were HIV-positive had been seen as having a ‘communicable disease of public health significance’ according to CDC guidelines (US Department of Homeland Security, 2010). Thus, for official purposes, immigrants who had lawfully come to the USA. prior to that time had all undergone a blood test and had been confirmed as HIV-negative. However, a retrospective chart review study on Boston-area immigration showed that only 36% of foreign-born immigrants had been screened for HIV (Waldorf et al. 2013). That means, there were many undocumented immigrants in the metropolitan areas. In addition, one study reported that being born outside the USA and perceiving a lower social economic status were factors associated with greater levels of HIV risk (Halkitis & Figueroa, 2013).

BACKGROUND

In the area of HIV treatment, studies have shown that many immigrants who develop HIV are diagnosed at a late stage of the pre-AIDS infection (Kang et al. 2003, Chin et al. 2011). Consequently, many of them go on to develop full-blown AIDS (Camoni et al. 2013). According to projections based on the general population, there should be many more HIV-infected immigrants than has been reported to health authorities. This suggests that the difference is accounted for by people who have the disease but have not sought treatment (Chen et al. 2014, Chin et al. 2011). Many HIV-positive immigrants delay seeking healthcare until they are very ill. These individuals often present for the first time in the emergency room with symptoms of full-blown AIDS (Vazquez, 2005).

As is true for other immigrants, HIV-positive immigrants arrive in their new home with dreams that they want to fulfill. However, for immigrants diagnosed with HIV, their ‘American dream’ has been shattered. (For the purposes of this paper, the American dream represents an immigrant's perceived level of self-actualization. Self-actualization is defined as a person's ability to set reasonable goals and then attain them.) HIV can cause immigrants to lose their sense of self as the disease forces them to give up their professional career, their hobbies and their family support (Williams, 2006). Many of the HIV-positive individuals in this study–especially those who had gotten a late diagnosis–experienced despair and felt that they were useless to society, seeing their lives as something no longer valuable. However, those who received an early diagnosis tended to have increased social support, which helped them explore new possibilities, create new meaning in their lives and rediscover themselves (Feitsma et al. 2007). When HIV-positive individuals were able to find new meaning in their lives, they began to feel that there were other things more important than the HIV diagnosis and they found they could recreate their American dream with self-love and self-acceptance (Williams, 2006).

Not surprisingly, immigrants diagnosed with HIV have additional stress from dealing with a life-threatening disease in a country that is new to them, a country with different laws and a different culture (Vazquez, 2005). Under these circumstances, English proficiency becomes the key to accessing healthcare resources and communicating with healthcare providers (Chen, 2013). In other words, immigrants must be able to acculturate, but acculturation comes with stresses of its own, stresses that are strongly associated with feelings of depression, anxiety and frustration and behaviors such as substance abuse (Bhattacharya, 2008). The HIV-positive individuals in this study talked about resources that decreased acculturation stress and most prominent among these resources was support from HIV healthcare providers and peers (Simoni et al. 2009, Simoni et al. 2011). In addition, ongoing support from family members both in the host country and the country of origin also alleviated acculturation stress (Starks et al. 2008).

THE STUDY

Aims

It is important to understand how API immigrants manage the acculturation process while living with HIV. Therefore, in this paper, we explore how these immigrants redefine self-actualization (their American dream) after they have been diagnosed with HIV and specifically how the resulting depression that often occurs interacts with the immigrants’ process of acculturation and self-actualization.

Design

We conducted 30 in-depth interviews with HIV-positive API in two cities (16 in San Francisco and 14 in New York City). Additionally, cross-sectional audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) were conducted with a convenience sample of 50 HIV-positive API (29 in San Francisco and 21 in New York City). A mixed-methods study was employed for this project. All the in-depth interviews were audio-recorded except for one, which was typed while the participant talked. All interviews were conducted in English or Mandarin according to the study participant's preference. Consent was obtained from all the study participants and each received a small payment in exchange for their participation. The inclusion criteria for potential participants were that they were (a) HIV-positive, (b) self-identified as API, (c) at least 18 years of age and (d) willing to share their personal stories with the researchers. The study took place from January to June 2013.

Settings and Participants

This project involved three service provider agencies. First was the Asian & Pacific Islander Wellness Center (A&PI Wellness Center) in the San Francisco Bay area. The A&PI Wellness Center is the oldest non-profit HIV/AIDS service organization in North America targeting API communities. Second was the Chinese-American Planning Council, Inc. (CPC). CPC offers HIV/AIDS services and is located in New York City's Chinatown. Third was the Asian/Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDSCommunity Health Center (APICHA Community Health Center) in New York City, a non-profit organization providing HIV/AIDS-related services, education and research to API communities. Participants were recruited from these three settings.

Data Collection

Qualitative Component

HIV-positive API who were interested in the study met with the researchers, who explained the study, answered questions and obtained written consent. In-depth interviews were audio-recorded, conducted in English or Mandarin and transcribed into English or Chinese after the session. Representative quotations were selected from the transcripts and translated into English for publication. Each interview took about 1-2 hours and was carried out in a private location. Bilingual researchers (English and Chinese) conducted all the in-depth interviews.

Interviewers used an interview guide during in-depth interviews to inquire about participants’ remembered perceptions of their immigration process, acculturation and depression before and after their HIV diagnosis. Specific questions included the following: ‘Tell me when and how you decided to come to the United States.’, ‘How well did you fit into U.S. culture?’ and ‘How do you feel now, with HIV?’ Theinterviewer also asked each participant to describe one specific experience of a stress-related episode that they had experienced. Generally, study participants led the discussion, with the interviewers prompting them as needed.

Validity and Reliability

Atlas.ti software (Scientific Software Development Version 5.0, 2005) was used to code the data and do qualitative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). After coding the data into broad topic categories, the researchers generated reports summarizing the range of responses. The authors examined the transcripts separately and identified codes from the code list to correspond to themes that emerged in the narratives. The authors then discussed the coding to resolve any disagreements in the meaning and assignment of codes as well as general patterns observed in the data.

Quantitative Component

Study participants finished a cross-sectional 1-hour ACASI computer survey that included instruments of demographics, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and demonstrated acculturation and self-actualization scales. These well-tested scales have been used in many Asian populations and have shown good reliability and validity over time (Cheng and Chan, 2005).

Demographics

Participants’ ethnicity, age, country of origin, gender, sexual preference, marital/partner status, income, education level, residency, length of stay in the U.S. and employment status were collected via ACASI.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

This 20-item scale developed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies was used. Cronbach's alpha for the CES-D scale was 0.77 (Rao et al. 2012). In addition, CES-D has been used in API populations with satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.86) (Li and Hicks, 2010).

Acculturation Scale

The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale was used (Suinn et al. 1987). This 21-item Likert-type scale measures language use, friendship patterns and ethnic identity in Asian populations. A final acculturation score is calculated by dividing the total ratings value by 21; hence a score can range from 1.00 (low acculturation) to 5.00 (high acculturation). Several studies on Asian populations have used this scale with internal consistency ranging from 0.72- 0.91 (Yang and Wang, 2011, Chen et al. 2012, Venkatesh et al. 2013).

Self-actualization

A question from the self-efficacy scale was used to help study participants rate their goal achievement: ‘I am certain that I can accomplish my goals’ —with possible answers ranging from 1 (don't agree at all) to 4 (strongly agree).

Data Analysis

For quantitative data analysis, descriptive and bivariate statistics were used to examine the relationship among proportion of lifetime in the USA, acculturation, CES-D, hope for self-actualization and selected demographics. Multivariable regression analysis was used to test the relationships among CES-D, acculturation and self-actualization. To test whether acculturation interacted with self-actualization, an additional term to describe interaction between acculturation and self-actualization was entered into the model. Because the sample size was small, covariates entered into the model were limited to 10 variables to avoid the issue of over-fitting. Finally, the Huber-White robust estimator was used to calculate standard error ranges.

Ethical Considerations

The ethical review board at the University approved the study. Before data collection, research staff explained the study purpose and the participants’ rights according to the University's informed consent policy. The participants were assured that their responses would be confidential and anonymous. All 50 study participants who met the study criteria and agreed to participate provided signed informed consent.

RESULTS

Qualitative Data

Twenty-six male (87%) and four female (13%) participants completed the in-depth interviews. Ages ranged from 32-69 years old, with 6 participants (20%) who were 31-40 years old, 8 (27%) who were 41-50 years old, 11 (37%) who were 51-60 years old and 4 (13%) who were 61-69 years old. Ethnic backgrounds for the study participants were Chinese (36%), Filipino (22%), Japanese (6%), Vietnamese (14%), Malaysian (6%), Burmese (2%), Cambodian (4%), Taiwanese (2%), Laos (2%), Indonesian (2%) and Pacific Islander (4%). The largest education level category was ‘less than a high school education’ (37%; n = 11), followed by 33% ‘completed college degree’ (n = 10). Most participants (73%; n = 22) were immigrants to the USA and the average duration of time in the USA was approximately 23 years (with a range from 6-40 years). Some of the study participants (37%; n = 11) had children and most were not working (73%; n = 22). In this cohort, most of the study participants’ CD4 counts were in the normal range (M = 540 cells/mm3; range from 295-895 cells/mm3). Site comparison on the contributing factors between New York and San Francisco has been reported in a separate paper (Chen et al. 2014).

Overall, many participants who stayed in New York stated that many of their relatives were in the States; therefore, the study participants decided to join them. In addition, they had the perception that it might be easier to earn money in the States. Other Filipinos and South Asians came to the States because their parents decide to emigrate to the States. Therefore, they spent their teenage years here. One 42-year-old Vietnamese-American man said: ‘Vietnam country is a war country. My family don't want us to go to the war. The communist police will take me to the war. And my family don't want to me go to the war. The life there is very difficult. That is why I am here.’ For those who had lower acculturation, they felt that as long as they could survive in the States, they would be content. Compare to those who had higher acculturation levels, they still have their dream to fulfill. However, they had all adjusted and compromised their ideal lives after being diagnosed with HIV. Major themes extracted from the in-depth interviews included self-actualization, acculturation and depression. Each of the themes is discussed below.

Self-actualization

Participants described their ‘American dream’ or specific things they planned to achieve after they arrived in the USA One of them wanted to open a Chinese restaurant, for example, to earn money to give his family a better life. Another wanted to become a respected and well-known scientist. However, when they got an HIV diagnosis, their new dream became to merely get settled quickly in their new home and find good healthcare providers who could understand their special issues as HIV-positive immigrants. As one 60-year-old Chinese man stated:

In China, everyone wanted to go to the United States. I dreamt about going abroad, too. Now I am here with this disease. Compared to my friends back in China, now they are all rich and live in the mansions [...] I am fine now, at least, I have my family with me. The only thing that I regret is that I am still undocumented.

When participants experienced the acute health crisis of HIV/AIDS, most of their daily effort began being channeled to securing affordable treatment for their health and survival, while other tasks and activities critical to achieving their dreams–tasks such as mastering English and picking up new skills for career development in the USA–became secondary. This was explicitly demonstrated by one 48-year-old Chinese male in New York when he explained why he could not speak fluent English despite having resided in the USA for about two decades. ‘I did have my American dream,’ he said, ‘but after I was diagnosed in ‘93, my dream was shattered. Once I knew I had this disease, I didn't even know how long I would live. [After that] I had no interest in learning English; that was no longer my priority.’

Acculturation

Despite the majority of our interviewees expressing that they were excited when they first immigrated to the USA—a place where they thought they could pursue their goals and achieve their American dreams—they often went through a challenging acculturation process that was further complicated by an HIV diagnosis. Acculturation experiences differed based on the degree of developmental tasks required of each immigrant on his/her arrival in the USA These tasks ranged from having to learn a new language (English) to acquiring new cultural norms for school to developing new career and interpersonal skills (Oppedal et al. 2005). Participants reported that receiving an HIV diagnosis drastically changed the course of their acculturation. For some, their diagnosis and declining health condition seriously delayed or even terminated their acculturation process. Obtaining necessary healthcare for HIV/AIDS, however, requires a relatively high level of acculturation, given the language barrier and the differences between the healthcare systems in the USA and in the immigrants’ home countries. Some of the participants developed special strategies to quickly familiarize themselves with the U.S. healthcare system so they could get the assistance they needed. For example, one 53-year-old Chinese man noted that in the USA he was receiving approximately $300 per month and lived in subsidize housing. ‘This would be impossible in my hometown!’ he said. Also, a 37-year-old Chinese man described joining an English-speaking church in his local community, from which he received not only friendship but also information essential to his health and survival in the USA:

I got referred into an English-speaking only church after I was diagnosed with HIV. I was learning everything about America from there and I got some good friends—Caucasian and Hispanic—to teach me how to navigate through the healthcare system. I tried to get everything I needed from [those friends].

Depression

A majority of study participants (n=18; 72%) shared about having depressive moods that often came on after periods of stress from the combination of the acculturation process and HIV-related stigma. One 48-year-old Filipino man reported that he needed to ‘shop around’ to find a healthcare provider that could better meet his needs—medical care that took both his HIV and API cultural background into consideration. He was constantly changing his healthcare providers and during this time he grew more depressed. He said, ‘From the time of diagnosis, I went through depression, a time of helplessness, for several months. Then I talked to my providers and went to different organizations until I found one that is supportive.’

Another 53-year-old female from Vietnam described her experience in the immigration process with HIV: ‘I thought that when I left Vietnam, I wanted to come here to change my life. But when I came here, my life did not get better but got more terrible, you know. I complained by myself, but at that moment, I was very sad and depressed.’ For participants who went through the immigration process, getting diagnosed with HIV was another critical stressor that they needed to endure while facing an uncertain future and managing the process of settling down with their families in a new country. The 53-year-old Vietnamese woman went on to say:

I sat on my chair and thought, What should we do? My life, my dad and my children? I don't see a future ahead of them. Sometimes I am really sad and I don't know what is going to happen and what is going on [in this country]. Every day, I worry about what is going to happen tomorrow. I always worry about what will happen tomorrow, but I have to hide my feelings. I always act happy in front of my children, my husband, my family, because I need to be strong.

One 45-year-old Indonesian man shared that after he had found the means to survive and had reached a considerable level of acculturation in the USA, the accidental disclosure of his diagnosis caused him to lose all he had. This loss in turn caused him to have a serious mental health crisis. He said:

After I had been working at the same place for 7 years, my employer, who was also an Asian immigrant, knew that I had gotten this disease. I lost everything, including my house, my job and my family. I was so depressed, thinking about the disease I had and how I had not gotten treated for 5 years, with my [HIV-related] symptoms getting worse. So one day, my symptoms got so bad, I felt like I was dying.... I couldn't breathe. ... Luckily, I had friends who introduced me to [the API HIV clinic]. They give me such good care. I really appreciate them.

The study revealed how acculturation and self-actualization are closely intertwined. For those who had lower acculturation, they felt that, as long as they could survive in the USA, they would be satisfied. Survival had become their new American dream. Those who had a higher acculturation level felt they could still fulfill their original dream even with HIV in their lives. Thus, although all study participants found they had to adjust and compromise their dreams, their individual acculturation level affected how much adjusting and compromising each one had to do.

Study participants shared that they had learned much from friends who taught them how to adapt and survive in the USA. One 51-years-old Chinese-American man said that he enjoyed talking with his American friends who listened to him and respected what he said, even though his English was not fluent. ‘Americans won't cheat and also, America is full of opportunities, a land of milk and honey. I mean a lot of opportunities. It is really nice to come over here,’ he said, contrasting his experience with Americans to his experience with some of his Chinese friends, who had borrowed money from him but never returned it. Others who were more acculturated to the USA preferred to spend time with other Asians. A 32-year-old Filipino men said, ‘Because I am Asian. As much as we are the same as everybody else, there are still issues that Asians are experiencing different issues than white or black people experienced. And if I can choose a place, I would like to choose a place where I can be at home.’ And he continued that ‘I am working and I have my own time. I am happy with it; I can't ask for more. As long as I can pay my bills, I can eat. I have my family and friends with me and I have medications; I don't need to pay for the copay. I am happy.’

Quantitative Analysis

For the quantitative analysis section, the participant sample that completed the ACASI survey was 16% female (n=8) and 84% male (n=42). Their ages ranged from 31-69 years old, with 10 participants (20%) from 31-40, 15 (30%) from 41-50, 17 (34%) from 51-60 and 8 (16%) from 61-69 years old. Ethnic background for the study participants was Chinese (38%), Southeast Asian (30%), Filipino (22%) and others (10%). For data analysis purposes, we divided these groups into four categories, which included Chinese (mainland Chinese and Taiwanese; n=19), Filipino (n=11), Southeast Asian (Vietnamese, Malaysian, Burmese, Cambodian, Indonesian, Lao; n=15) and others (Japanese, Pacific Islander; n=5). A majority of the study participants had less than a high school education (38%; n=19). Detailed demographic data and ethnic group comparisons are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Background and Bivariate Analysis

| Total | Chinese | Southeast Asians | Filipinos | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 50 | N = 19 | N = 15 | N = 11 | N = 5 | |

| Gender | % | % | % | % | % |

| Male | 84 | 84.21 | 80 | 90.91 | 80 |

| Education** | |||||

| < HS | 38 | 68.42 | 33.33 | 9.09 | 0 |

| HS | 32 | 21.05 | 33.33 | 45.45 | 40 |

| Associate Degree | 20 | 5.26 | 26.67 | 18.18 | 60 |

| College or Higher | 10 | 5.26 | 6.67 | 27.27 | 0 |

| Immigrants** | |||||

| Yes | 76 | 78.95 | 86.67 | 81.82 | 20 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.86 | 9.43 | 51.16 | 9.65 | 48.20 | 8.01 | 45.64 | 9.02 | 49.20 | 14.19 |

| Proportion of lifetime in U.S.** | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 0.27 |

| Acculturation** | 1.20 | 0.93 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 1.09 | 0.62 | 2.15 | 0.73 | 2.15 | 0.63 |

| CES-D* | 16.78 | 9.76 | 13.63 | 9.40 | 23.07 | 9.21 | 15.00 | 8.96 | 13.80 | 9.59 |

| Hope for self-actualization** | 2.52 | 1.01 | 2.00 | 0.92 | 2.53 | 0.86 | 2.91 | 0.80 | 3.60 | 0.91 |

P<0.05

P<0.01

All the estimates are based on bootstrap variances.

HS- High School

CES-D- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Ethnicities: Chinese (mainland Chinese and Taiwanese), Southeast Asian (Vietnamese, Malaysian, Burmese, Cambodian, Indonesian, Lao) and others (Japanese, Pacific Islander)

Chinese participants were the oldest group (mean age: 51 years old) compared with other study participants, although their average time in the United States was shorter than that of Filipinos and other API. Chinese participants were also the least acculturated and had the least hope for self-actualization. Southeast Asians had the shortest time in the USA and also the highest perceived stress and depression.

In multivariable regression analysis, the participants’ hope for self-actualization and its interaction with level of acculturation were statistically significant, although the main effect of acculturation and its square term (acculturation x acculturation) were not statistically significant (See Table 2). This suggests that hope for self-actualization and level of acculturation can interact with each other and can be associated with API HIV-positive patients’ mental health in a synergistic way. In other words, the relationships between participants’ levels of hope for self-actualization was contingent on their acculturation levels. The CES-D score for each API HIV-positive patients was associated with one of four levels of hope for self-actualization. These scores are presented in Figure 1. Because level of acculturation was a continuous variable, the CES-D scores were calculated on three levels of acculturation (low-25%, mid-50% and high-75%). It was clear that among those who had low acculturation, there was a huge gap in CES-D scores between those who had totally lost their sense of self-actualization and those who still believed they could succeed in the USA The decrease in CES-D score for the low-acculturated group is statistically significant (p = 0.02). However, for those who had higher acculturation, CES-D scores were flat and did not change significantly across the four levels of self-actualization. So, although graphically the CES-D scores look somewhat like a reverse U shape, statistically they are a flat line, representing non-significance.

Table 2.

Multivariable Regression in Relationships Between Acculturation and Self-actualization

| β Coefficient | SE | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Chinese | Ref. | -- | -- | -- |

| Southeast Asians | −2.10 | 1.74 | 0.236 | −5.65 - 1.45 |

| Filipino | −4.76 | 3.36 | 0.167 | −11.63 - 2.10 |

| Other | −8.87 | 3.75 | 0.025* | −16.54 - −1.20 |

| Age | −3.12 | 0.97 | 0.003** | −5.11 - −1.13 |

| Acculturation | −0.37 | 6.27 | 0.953 | −13.19 - 12.45 |

| Acculturation X Actualization | −2.75 | 1.67 | 0.111 | −6.17 - 0.67 |

| Actualization | ||||

| Never true | Ref. | -- | -- | -- |

| Barely true | −11.41 | 5.56 | 0.049* | −22.78 - −0.04 |

| Moderately true | −9.71 | 5.88 | 0.110 | −21.73 - 2.32 |

| Exactly true | −18.07 | 8.67 | 0.046* | −35.79 - −0.34 |

| Acculturation X Actualization | ||||

| Never true | Ref. | -- | -- | -- |

| Barely true | 10.81 | 5.01 | 0.039* | 0.57 - 21.05 |

| Moderately true | 8.68 | 5.03 | 0.095† | −1.62 - 18.98 |

| Exactly true | 11.87 | 6.05 | 0.059† | −0.49 - 24.24 |

P< 0.01

P< 0.05

< 0.1

SE- Standard Error

CI- Confidence Interval

Ethnicities: Chinese (mainland Chinese and Taiwanese), Southeast Asian (Vietnamese, Malaysian, Burmese, Cambodian, Indonesian, Lao) and others (Japanese, Pacific Islander)

Figure 1.

Correlations among depression, self-actualization and acculturation levels. CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression ScaleS

DISCUSSION

Most immigrants arrive in their new land with hope for achieving their American dream by providing a better economic security for their families (Shobe et al. 2009). The ones who achieve this dream have stable employment, healthcare access and social support (Shobe et al. 2009). However, HIV-positive API are very likely to face job loss, to spend time seeking specialized HIV healthcare access and to disconnect from their usual social support due to HIV-related stigma. In this study, depression symptomatology presented in many study participants. The study results showed that immigrants who had low-to-moderate acculturation to U.S. society tended to suffer with depression symptoms and also tended to have the lowest confidence in achieving their dreams. This was especially true for the lower-acculturated participants who came from China and Southeast Asia. Being diagnosed with HIV forced these individuals not only to learn to navigate the U.S. health system but also to acquaint themselves with the special terminology related to their illness (Saint-Jean et al. 2011). The study participants shared that, although the U.S. immigration system had not been welcoming to them—the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) ‘immigration ban’ for HIV-positive residents expired only in 2010 (Dwyer, 2010)—once they had arrived and finally gotten connected with the healthcare system, they experienced a great deal of empathy and assistance from healthcare providers.

Generally, studies have shown that immigrants have better physical health compared with the non-immigrant population in their host country (Donnelly and McKellin, 2007, Shedlin et al. 2005, De Alba et al. 2005). Some studies have focused specifically on the relationship between immigrant stress and health-related conditions (Yang and Wang, 2011, Miller et al. 2011, Gonzalez-Guarda et al. 2011, Ding and Hargraves, 2009) and at least one has demonstrated significant increases in psychological stress among immigrants as compared with the general population before, during and after the immigration process (Torres and Wallace, 2013). When HIV is involved, stress is only exacerbated. Besides the physical discomforts and medical complications of the disease, API HIV-positive immigrants suffer from significant HIV-related stressors (Noh et al. 2012).

HIV-positive immigrants experience both risk factors and protective factors for mental illness (Alegria et al. 2008). While many participants in this study suffered from leaving the comfort of their home environment, some reported that they had come to the USA specifically to flee the stress and stigma associated with being gay. In this study, participants reported that they enjoyed the greater sexual freedom in New York and in San Francisco but still feared that relatives back home would learn of their behavior in the USA; therefore, some of them avoided members of their own ethnicity locally. Thus, they lost access to social support they might have otherwise had. At the same time, though, they found that they could use their limited English to make new friends, which then increased their acculturation to the host society and broadened their support network.

Considering the social stigma and the relatively low level of HIV healthcare in their home countries (Li et al. 2013, Rao et al. 2012, Li et al. 2011), being diagnosed with HIV in the USA was not necessarily a bad outcome for some participants. In participants’ home countries, social welfare and case management are in a relatively low state of development (Ishikawa et al. 2010, Zhou, 2008). In some regions, HIV-related social services and case management are non-existent (Vazquez, 2005). By contrast, HIV medication and support are available free to low-income residents in the USA and many HIV-positive API in this study reported that they were relieved when they discovered this fact. As one participant said, after adjusting to the realities of HIV, he would now be pursuing a different kind of American dream—the dream of surviving.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, study participants came from 11 different ethnic backgrounds and speak a variety of languages. Some of them (for example, Filipinos) typically arrived in the USA with fluent English, while others (Chinese) did not. However, since HIV-positive API are a hard-to-reach population, we decided to keep the sample broad, while controlling for ethnicity and study site to obtain a critical sample size. Second, we recruited HIV-positive participants from two sites (New York and San Francisco) that differ in significant ways. New York study participants, for example, tended to have lower education levels with less acculturation to American society compared with San Francisco participants. However, all participants, regardless of site, went through the same process to learn about the U.S. healthcare system; they all learned via the same community-based organizations that assisted in their HIV care. Third, the relatively small sample size of the cross-sectional survey limited our ability to use more powerful statistical techniques, such as structural equation modeling. Finally, causal inferences should be drawn cautiously due to the cross-sectional nature of the data.

CONCLUSIONS

Immigrants in the USA usually have better health compared with native residents and they come in hopes of achieving their dreams in a new land. However, with a diagnosis of HIV, their dreams may need to be revised. In this study, individuals who were less acculturated had less confidence to achieve their dreams, compared with well-acculturated participants. While seeking healthcare in the USA, API immigrants are forced to acculturate more quickly. They are required to learn not just English but also specific HIV-related terminology and are also forced to learn how to navigate the U.S. healthcare system. For healthcare providers, intervention design should focus on enhancing acculturation and improving navigation through the U.S. healthcare system, as well as on detecting depression and providing coping strategies. This will enable HIV-positive API to experience a better quality of life and to achieve their revised American dream.

Summary statement.

Why is this research or review needed?

HIV's impact among Asian immigrants has not been adequately studied. There are many facets to the way HIV uniquely affects immigrants and these include disease treatment, disease prevention and impact of immigration policy.

In this study, we explored how Asians and Pacific Islanders immigrants readjust their self-actualization after being diagnosed with HIV and specifically how the resulting post-diagnosis depression can interact with an immigrant's process of self-actualization and acculturation.

What are the key findings?

Acculturation, self-actualization and depression are key issues for the HIV-positive Asians and Pacific Islanders population.

Asians and Pacific Islanders with lower acculturation suffered more from depression and impaired self-actualization.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

Healthcare providers should periodically evaluate HIV-positive immigrants’ mental health. Depression and acculturation levels should be included in the evaluations.

Intervention design should focus on enhancing acculturation and improving immigrants’ abilities to navigate through the U.S. healthcare system. Interventions for HIV-positive Asians and Pacific Islanders should include measures to detect depression and should impart coping skills.

Acknowledgement/Funding Statement

This study was supported in part by 5R25MH087217 (PIs: Barbara Guthrie & Jean Schensul) funded by NIH-NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health). In addition, Dr. Chen acknowledges Dr. Merrill Singer as the mentor during her training under Research Education Institute for Diverse Scholars (REIDS) in Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) at Yale University that offered her a chance to design and conduct this important study. Also, this publication was supported (in part) from research supported by an NIH funded program (1K23NR014107; PI: Wei-Ti Chen).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Author Contributions:

-

1)substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

-

2)drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

References

- ALEGRIA M, CANINO G, SHROUT PE, WOO M, DUAN N, VILA D, TORRES M, CHEN CN, MENG XL. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:359–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APPLIED RESEARCH CENTER AND THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICANS (NCAPA) Best Practices: Research Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders [Online] Applied Research Center and the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA); 2013. [September, 13 2013]. Available: ncapaonline.org. [Google Scholar]

- BHATTACHARYA G. Acculturating Indian immigrant men in New York City: applying the social capital construct to understand their experiences and health. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMONI L, RAIMONDO M, REGINE V, SALFA MC, SULIGOI B. Late presenters among persons with a new HIV diagnosis in Italy, 2010-2011. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN L, JUON HS, LEE S. Acculturation and BMI among Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese adults. J Community Health. 2012;37:539–46. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN W-T. Chinese female immigrants english-speaking ability and breast and cervical cancer early detection practices in the new york metropolitan area. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:733–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.2.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN WT, GUTHRIE B, SHIU CS, YANG JP, WENG Z, WANG L, KAMITANI E, FUKUDA Y, LUU BV. Acculturation and perceived stress in HIV+ immigrants: depression symptomatology in Asian and Pacific Islanders. AIDS Care. 2014:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.936816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG ST, CHAN AC. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in older Chinese: thresholds for long and short forms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:465–70. doi: 10.1002/gps.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIN JJ, LI MY, KANG E, BEHAR E, CHEN PC. Civic/sanctuary orientation and HIV involvement among Chinese immigrant religious institutions in New York City. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 2):S210–26. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.595728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE ALBA I, HUBBELL FA, MCMULLIN JM, SWENINGSON JM, SAITZ R. Impact of U.S. citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:290–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING H, HARGRAVES L. Stress-associated poor health among adult immigrants with a language barrier in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:446–52. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONNELLY TT, MCKELLIN W. Keeping healthy! Whose responsibility is it anyway? Vietnamese Canadian women and their healthcare providers' perspectives. Nurs Inq. 2007;14:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DWYER D. U.S. Ban on HIV-Positive Visitors, Immigrants Expires. Jan. Vol. 5. ABC News; 2010. p. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FEITSMA AT, KOEN MP, PIENAAR AJ, MINNIE CS. Experiences and support needs of poverty-stricken people living with HIV in the Potchefstroom district in South Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ-GUARDA RM, VASQUEZ EP, URRUTIA MT, VILLARRUEL AM, PERAGALLO N. Hispanic women's experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence and risk for HIV. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22:46–54. doi: 10.1177/1043659610387079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALKITIS PN, FIGUEROA RP. Sociodemographic characteristics explain differences in unprotected sexual behavior among young HIV-negative gay, bisexual and other YMSM in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:181–90. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSIEH HF, SHANNON SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIKAWA N, PRIDMORE P, CARR-HILL R, CHAIMUANGDEE K. Breaking down the wall of silence around children affected by AIDS in Thailand to support their psychosocial health. AIDS Care. 2010;22:308–13. doi: 10.1080/09540120903193732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANG E, RAPKIN BD, SPRINGER C, KIM JH. The ‘Demon Plague’ and access to care among Asian undocumented immigrants living with HIV disease in New York City. J Immigr Health. 2003;5:49–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1022999507903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEONG F, PARK YS, KALIBATSEVA Z. Disentangling immigrant status in mental health: psychological protective and risk factors among latino and asian american immigrants. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83:361–71. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI L, WU Z, LIANG LJ, LIN C, GUAN J, JIA M, ROU K, YAN Z. Reducing HIV- Related Stigma in Health Care Settings: A Randomized Controlled Trial in China. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:286–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI X, ZHANG L, ZHAO J, ZHAO G, FANG X, LIN X, STANTON B. Parental HIV/AIDS disclosure, stigma and psychosocial consequences among AIDS orphans in Henan, China The 10th AIDSIMPACT International Conference. Santa Fe.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- LI Z, HICKS MH. The CES-D in Chinese American women: construct validity, diagnostic validity for major depression and cultural response bias. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175:227–32. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER MJ, YANG M, FARRELL JA, LIN LL. Racial and cultural factors affecting the mental health of Asian Americans. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:489–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOH MS, RUEDA S, BEKELE T, FENTA H, GARDNER S, HAMILTON H, HART TA, LI A, NOH S, ROURKE SB. Depressive symptoms, stress and resources among adult immigrants living with HIV. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:405–12. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPPEDAL B, ROYSAMB E, HEYERDAHL S. Ethnic group, acculturation and psychiatric problems in young immigrants. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:646–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAO D, CHEN WT, PEARSON CR, SIMONI JM, FREDRIKSEN-GOLDSEN K, NELSON K, ZHAO H, ZHANG F. Social support mediates the relationship between HIV stigma and depression/quality of life among people living with HIV in Beijing, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23:481–4. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAINT-JEAN G, DEVIEUX J, MALOW R, TAMMARA H, CARNEY K. Substance Abuse, Acculturation and HIV Risk among Caribbean-Born Immigrants in the United States. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011;10:326–32. doi: 10.1177/1545109711401749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEDLIN MG, DECENA CU, OLIVER-VELEZ D. Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:32S–37S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHOBE MA, COFFMAN MJ, DMOCHOWSKI J. Achieving the American dream: facilitators and barriers to health and mental health for Latino immigrants. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2009;6:92–110. doi: 10.1080/15433710802633601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMONI JM, HUH D, FRICK PA, PEARSON CR, RASIK MP, DUNBAR PJ, HOOTON TM. Peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral modifying therapy in Seattle: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:465–473. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181b9300c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMONI JM, NELSON KM, FRANKS JC, YARD SS, LEHAVOT K. Are peer interventions for HIV efficacious? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1589–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9963-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STARKS H, SIMONI J, ZHAO H, HUANG B, FREDRIKSEN-GOLDSEN K, PEARSON C, CHEN WT, LU L, ZHANG F. Conceptualizing antiretroviral adherence in Beijing, China. AIDS Care. 2008;20:607–14. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUINN RM, RICKARD-FIGUEROA K, LEW S, VIGIL P. The Suinn-Lew Asian self- identity acculturation scale: An initial report. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1987;4:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- TORRES JM, WALLACE SP. Migration circumstances, psychological distress and self- rated physical health for latino immigrants in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1619–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENSUS BUREAU US. Hispanic and Asian Populations Grew Fastest During the Decade [Online] US Census Bureau; 2011. [May 12 2014]. Available: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn125.html. [Google Scholar]

- US DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY . Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection Removed from CDC List of Communicable Diseases of Public Health Significance [Online] US Department of Homeland Security; 2010. [September 13 2013]. Available: http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.5af9bb95919f35e66f614176543f6d1a/?vgnextchannel=68439c7755cb9010VgnVCM10000045f3d6a1RCRD&vgnextoid=1a05cc5222ff5210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD. [Google Scholar]

- VAZQUEZ B. My American dream. Res Initiat Treat Action. 2005;11:30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VENKATESH S, WEATHERSPOON LJ, KAPLOWITZ SA, SONG WO. Acculturation and glycemic control of Asian Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2013;38:78–85. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9584-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALDORF B, GILL C, CROSBY SS. Assessing Adherence to Accepted National Guidelines for Immigrant and Refugee Screening and Vaccines in an Urban Primary Care Practice: A Retrospective Chart Review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS AL. Perspectives on spirituality at the end of life: a meta-summary. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:407–17. doi: 10.1017/s1478951506060500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG YM, WANG HH. Acculturation and health-related quality of life among Vietnamese immigrant women in transnational marriages in Taiwan. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22:405–13. doi: 10.1177/1043659611414144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU YR. Endangered womanhood: Women's experiences with HIV/AIDS in China. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:1115–26. doi: 10.1177/1049732308319924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]