Abstract

Objectives

Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) varies by race/ethnicity and modifies the association between gestational weight gain (GWG) and adverse pregnancy outcomes, which disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minorities. Yet studies investigating whether racial/ethnic disparities in GWG vary by pre-pregnancy BMI are inconsistent, and none studied nationally representative populations.

Methods

Using categorical measures of GWG adequacy based on Institute of Medicine recommendations, we investigated whether associations between race/ethnicity and GWG adequacy were modified by pre-pregnancy BMI [underweight (<18.5kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2), or obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) ] among all births to Black, Hispanic, and White mothers in the 1979 USA National Longitudinal Survey of Youth cohort (n=6849 pregnancies; range=1-10). We used generalized estimating equations, adjusted for marital status, parity, smoking during pregnancy, gestational age, and multiple measures of socioeconomic position.

Results

Effect measure modification between race/ethnicity and pre-pregnancy BMI was significant for inadequate GWG (Wald test p-value=0.08). Normal weight Black (Risk Ratio (RR)=1.34, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18, 1.52) and Hispanic women (RR=1.33, 95%CI: 1.15, 1.54) and underweight Black women (RR=1.38; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.79) experienced an increased risk of inadequate GWG compared to Whites. Differences in risk of inadequate GWG between minority women, compared to White women, were not significant among overweight and obese women. Effect measure modification between race/ethnicity and pre-pregnancy BMI was not significant for excessive GWG.

Conclusions

The magnitude of racial/ethnic disparities in inadequate GWG appears to vary by pre-pregnancy weight class, which should be considered when designing interventions to close racial/ethnic gaps in healthy GWG.

Black and Hispanic women and children in the United States (US) have disproportionately more adverse birth outcomes and obesity (1-3). Gestational weight gain (GWG) disparities may be one explanation. The US Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently issued guidelines for optimal ranges of GWG (Table 1) for four categories of pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) to promote maternal and infant health (4). Yet in 2011, only 31% of women gained within the recommended IOM GWG range (5). Non-Hispanic Black women had the highest prevalence of weight gain below these guidelines, or inadequate GWG (23.2%; Hispanics: 22.6%, Whites: 18.5%). Over half (52%) of White women gained excessively, or above the IOM guidelines, as well as almost half of Blacks (48%) and Hispanics (44%) (5). Other studies confirm that Black and Hispanic women have lower GWG during pregnancy than Whites (6-11).

Table 1. Institute of Medicine Gestational Weight Gains in 2009 by Weight Class.

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 2009 IOM standards | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2)a | Total Weight Gain Range (lbs) | |

| Underweight | <18.5 | 28-40 |

| Normal Weight | 18.5-24.9 | 25-35 |

| Overweight | 25.0-29.9 | 15-25 |

| Obese (all classes) | ≥30.0 | 11-20 |

based on World Health Organizations BMI classification guidelies

Given rising obesity and growing evidence that GWG may contribute to setting the trajectory for poor health throughout life (12), the association between excessive GWG and large for gestational age and macrosomic infants has raised concern about children's subsequent increased risks for metabolic disorders and obesity (12-14), early menarche (15), and cardiovascular disease in adulthood (16). In mothers, excessive GWG is associated with antenatal and intra-partum complications (4) and obesity postpartum (4,13,14) and later in life (17,18). Many of these outcomes are also more common in Black and Hispanic populations (3,19). At the other extreme, inadequate GWG is associated with small for gestational age (SGA) infants (4,13,14), and preterm deliveries (4,14,20). These outcomes are also more common among Black mothers than White mothers (1,2,21).

Overall, while minority women appear to gain less weight than White women, they are still not protected from excessive GWG (19). However, knowledge is limited in several ways. First, few studies consider whether associations between race/ethnicity and GWG vary by pre-pregnancy BMI (e.g. 6-8,10); many only adjusted for BMI. Persistent racial/ethnic disparities in BMI among women of childbearing age make this an important consideration: currently, Black women age 20-39 have over twice the prevalence of obesity as White women (56.2% vs 26.9%), and Hispanic women have a 1.2 times higher prevalence (34.4%) (22). If, counter to current research assumptions, racial/ethnic disparities in GWG vary across pre-pregnancy weight classes (e.g., if Black-White differences in risk of excessive GWG are present among normal weight women but not among obese women), then current interventions to reduce racial/ethnic disparities may not target appropriate subgroups. Additionally, existing studies vary in their racial heterogeneity and may be underpowered to detect interaction by pre-pregnancy BMI among racial/ethnic groups. Sample characteristics of these studies ranged from small local samples (6,8,9) to regionally defined samples of economically disadvantaged women (10) to one study by Chu et al. (7) conducted in a sample from a national surveillance study. They also use different measures of GWG, including continuous and categorical overall GWG (6,7,10), trimester-specific GWG (23), and a combined measure of GWG and postpartum weight loss (9).

The IOM identified minority women as important targets for intervention to promote healthy weight gain but noted that limited national data and few studies that considered pre-pregnancy BMI prevented “drawing any conclusions about the influence of race ethnicity on GWG” (4, p.123). To address this gap, we analyzed data from the US 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) to determine whether racial/ethnic differences in inadequate and excessive GWG vary by pre-pregnancy weight class.

Methods

Sample

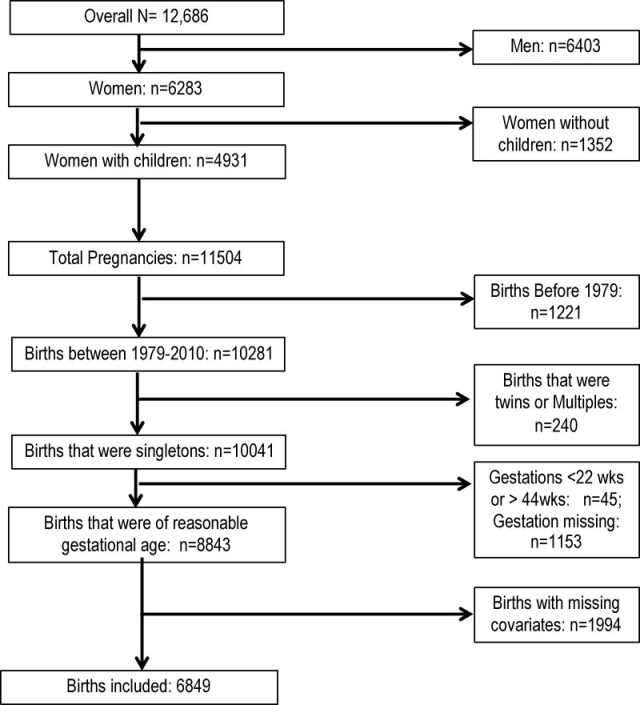

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics' NLSY79 (24) has followed a nationally representative sample of 12,686 men and women since 1979, when they were aged 14-22 years. Participants were interviewed annually from 1979 to 1994 and biennially to 2010. Participants were weighted to account for: non-response; oversampling of Blacks, Hispanics, and low-income non-Black, non-Hispanic individuals; and the national population. Female participants reported on pregnancies prospectively beginning in 1986, and retrospectively for earlier pregnancies (25). Our analysis included all singleton births to mothers occurring from 1979-2010, excluding births with implausible values for gestational age (<22 weeks and >44 weeks; n=45) (26). We further restricted to pregnancies with complete data on GWG, mother's race/ethnicity, and covariates of interest; Asian mothers (n=78) were excluded due to small sample size. The complete case sample size totaled 6849 pregnancies among 3835 mothers (Figure 1). Mothers contributed 1 to 10 pregnancies to our analysis (mean: 1.97; SD: 1.11). Our analysis was exempt from full human subjects review by the University of California, Berkeley Center for the Protection of Human Subjects as the data used are unidentifiable and publicly available online.

Figure 1. Observations from the NLSY79 Complete Cohort Remaining in Analytic Sample Based on Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Analytic Variables

Main Outcome

For each pregnancy, women self-reported their pre-pregnancy and pre-delivery weights. At the interview following the index pregnancy, women were asked, “What was your weight just before you became pregnant with [index child]?” and, “What was your weight just before you delivered?” for pre-pregnancy and pre-delivery weight, respectively. Because more than 10% of the sample had deliveries before term, and GWG is partially a function of gestational age, we calculated GWG adequacy, an estimated ratio of a woman's observed and expected amounts of weight gain at each week of gestation (27,28). Expected GWG was calculated based on IOM recommendations for amount of weight gain during the first trimester, which varied by pre-pregnancy BMI (underweight: 2kg; normal weight: 2kg; overweight:1kg; obese: 0.5kg; (4)), and rate of weight gain during the second and third trimester: expected GWG= recommended first trimester gain + (gestational age-13)*(rate of weight gain during the second and third trimesters). Observed GWG was the difference between a woman's weight right before delivery and her weight prior to pregnancy. We then divided observed GWG by expected GWG and used this ratio to classify women as gaining inadequately, adequately, or excessively. Recommendations were based on the 2009 IOM report and were pre-pregnancy BMI specific: 28-40 lbs for underweight (<18.5kg/m2), 25-35 lbs for normal weight (18.5-24.9kg/m2), 15-25 lbs for overweight (25-29.9kg/m2), and 15-20lbs for obese (≥30.0kg/m2) (4). Although GWG recommendations changed over our study period (4,29) and most NLSY pregnancies occurred before 2009, we utilized the 2009 categories which provide a range of weight gain for obese women. Ninety four percent of pregnancies were classified identically when using the 2009 and 1990 recommendations. Our reference group in statistical models was women who gained adequately, e.g . when comparing women who gained excessively to women who gained adequately, we excluded women who gained inadequately from that model and vice versa.

Covariates

Self-reported race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Black, and White) was our main independent variable of interest. We also included covariates widely considered to be confounders (e.g. (19,30)): pre-pregnancy BMI, mother's age at birth, parity (prior to the index pregnancy), marital status, smoking during pregnancy, gestational age of child, and infant's birth year. All covariates were collected at the time of pregnancy to capture any changes across pregnancies. We calculated pre-pregnancy BMI by dividing self-reported pre-pregnancy weight (kg) by height (m) self-reported closest to the pregnancy, squared. Height was reported in 1981, 1982, 1985, 2006, and 2008. We regression-calibrated height measures using correction factors derived from National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) III data to account for self-reporting bias (31). While error from weight self-reporting also exists (e.g. (32,33)), similar regression calibration techniques for pregnancy-related weight do not exist. BMI was categorized into the weight classes described above (4,34). Parity, maternal age at the time of the child's birth, and the birth year of the child were continuous variables. Models testing alternative functional forms of these covariates (parity as categorical, maternal age squared, and child's birth year as categorical) did not change our findings, so we kept them as continuous to retain power. Self-reported smoking during pregnancy (smoker/non-smoker) and marital status (married/never married or other) were both binary variables.

Since race and socioeconomic status (SES) are highly correlated in the US, it is often difficult to remove confounding effects of SES when investigating racial disparities in health outcomes (35,36). We used NLSY79's detailed socioeconomic data to control for several socioeconomic measures. Past-year employment was measured as unemployed (<10 hours per week), part-time employed (10-34 hours per week), and full-time employed (≥35 hours per week). Participant's mother's years of education were reported at baseline and participant's years of education attained were reported at each interview. Both were classified as less than high school graduation (<12y), high school graduation but not college graduation (12-15y), and college graduation or more (≥16y). We used a measure of income that accounted for family size, dividing total family income (in year 2000 dollars) by family size, raising it to the 0.38 power (37), and log transforming it to normalize the distribution.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated means, standard deviations, and percentages to describe the distribution of outcomes and covariates in our analytic sample. We assessed bivariable associations between covariates and race/ethnicity using t-tests for categorical and continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with log link functions to estimate risk ratios for race and GWG that accounted for clustering of pregnancies within women (using an exchangeable correlation structure and robust standard errors). We estimated crude associations, adjusted associations controlling for relevant covariates, and interaction models to determine whether racial/ethnic differences in GWG varied by pre-pregnancy weight class. In all models, continuous variables were median-centered. We set type I error thresholds at 0.05 for main association parameters. We used Wald tests to assess the significance of interaction for all cross-product interaction terms at the p≤0.10 level, since assessment is underpowered at the 0.05 level (38). If significant interaction was detected, we reported the magnitude of racial differences within each stratum of pre-pregnancy weight class. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether bias from missing data impacted estimated associations. Missing values in our covariates ranged from 0.3% to 14.4% (Appendix Table A1), and those excluded from our complete case analysis were more likely to be non-White, underweight, less educated, unemployed, unmarried, have lower parity, have lower income, have children earlier and at younger ages (Appendix Table A2). We used Stata 11.0's multiple imputation package to predict missing values for covariates. We then estimated the crude, adjusted, and interaction models using the imputed data sets. All models were estimated using Stata 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, 2009-2011).

Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of variables in the final weighted analytic sample and by race/ethnicity. The mean GWG was 14.1 kilograms (31.1 pounds); on average, women gained 127% of their expected GWG for BMI and gestational age (corresponding to 40 pounds for a normal weight woman at 40 weeks gestation). A plurality of women (44.4%) gained excessively, with 32.5% gaining adequately and 23.1% gaining inadequately. Most women began pregnancy at a normal BMI; only 25.5% started pregnancy overweight or obese. Black women gained the highest percent of their expected weight gain, while Hispanic women achieved the lowest. However, inadequate weight gain was still more common in Black and Hispanic women than in White women. Also, a larger percent of minority women began their pregnancies overweight or obese, had lower educational attainment at the start of pregnancy, and had mothers who were less likely to have graduated from high school.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Analytic Variables Overall and by Race/Ethnicity.

| Total (births n= 6849; mothers n= 3835) |

White (births n= 4134; mothers n= 2375) |

Black (births n= 1624; mothers n= 907) |

Hispanic (births n= 1091; mothers n= 553) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Un-weighted N |

Weighted Mean (SD) |

Weighted % |

Weighted Mean (SD) |

Weighted % |

Weighted Mean (SD) |

Weighted % |

Weighted Mean (SD) |

Weighted % |

p- value |

|

|

| ||||||||||

| Racea | ||||||||||

| White | 2375 | 82.4% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Black | 907 | 12.5% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Hispanic | 553 | 5.1% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| GWG | 6849 | 14.1 (6.6) | 14.3 (6.3) | 13.5 (7.8) | 13.3 (7.0) | <0.001 | ||||

| GWG Ratio | 6849 | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.8) | 0.02 | ||||

| GWG Adequacy | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Inadequate | 1721 | 23.1% | 21.7% | 30.1% | 28.3% | |||||

| Adequate | 2067 | 32.5% | 34.0% | 24.9% | 28.1% | |||||

| Excessive | 3061 | 44.4% | 44.4% | 45.1% | 43.6% | |||||

| Pre-pregnancy Weight | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Underweight | 514 | 7.7% | 8.0% | 7.0% | 5.4% | |||||

| Normal | 4524 | 66.8% | 68.0% | 60.0% | 63.9% | |||||

| Overweight | 1190 | 16.4% | 15.4% | 20.1% | 21.9% | |||||

| Obese | 621 | 9.1% | 8.6% | 12.9% | 8.8% | |||||

| Parity | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 0 | 2705 | 42.3% | 44.5% | 30.9% | 35.0% | |||||

| 1 | 2408 | 35.4% | 35.5% | 35.6% | 33.4% | |||||

| 2 | 1145 | 15.2% | 14.2% | 20.2% | 17.8% | |||||

| ≥3 | 591 | 7.1% | 5.8% | 13.3% | 13.9% | |||||

| Education | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 1407 | 14.0% | 11.4% | 21.1% | 36.5% | |||||

| High school | 4437 | 66.4% | 66.4% | 70.7% | 56.5% | |||||

| College | 1005 | 19.6% | 22.2% | 8.2% | 7.1% | |||||

| Participant's Mother's Education | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 1104 | 29.8% | 25.2% | 48.1% | 79.6% | |||||

| High school | 1417 | 60.8% | 64.5% | 46.2% | 18.7% | |||||

| College | 192 | 9.4% | 10.2% | 5.7% | 1.6% | |||||

| Equivalized Incomeb | 6849 | 9.8 (1.2) | 10.0 (1.1) | 8.9 (1.3) | 9.3 (1.3) | <0.001 | ||||

| Employment | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 2392 | 30.1% | 28.2% | 39.1% | 37.8% | |||||

| Part-time | 2060 | 30.6% | 31.2% | 27.8% | 28.2% | |||||

| Full-time | 2397 | 39.3% | 40.6% | 33.1% | 34.0% | |||||

| Married | 4800 | 78.7% | 85.3% | 37.6% | 73.2% | <0.001 | ||||

| Smoking During Pregnancy | 1939 | 28.4% | 29.4% | 28.2% | 14.5% | <0.001 | ||||

| Gestational Age | 6849 | 38.6 (2.0) | 38.7 (2.0) | 38.4 (2.4) | 38.6 (2.0) | <0.001 | ||||

| Preterm Birth | 6849 | 11.7% | 11.5% | 14.1% | 10.0% | 0.03 | ||||

| Child's Birth Year | 6849 | 1988 (5.4) | 1988 (5.4) | 1987 (5.2) | 1987 (5.5) | <0.01 | ||||

| Mother's Age at Birth | 6849 | 26.74 (5.1) | 27.0 (5.1) | 25.5 (5.1) | 26.0 (5.3) | <0.001 | ||||

N represent mothers in the data set (N=3835)

Equivalized income was calcluated to adjust for family size. For a family of 4 in year 2000 (the year to which all incomes in our data set are standardized to) our mean equivalized income of 9.8 corresponds to an aggregate houshold income of $30,540.

Inadequate GWG

The risk of inadequate GWG differed significantly by race/ethnicity. Crude analysis indicated that Black (RR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.28, 1.55) and Hispanic women (RR: 1.27; 95%CI: 1.13, 1.43) had an increased risk of inadequate GWG compared to White women. After adjusting for socioeconomic, demographic, and maternal characteristics, this risk was somewhat attenuated (Black RR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.41; Hispanic RR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.40), but remained significant.

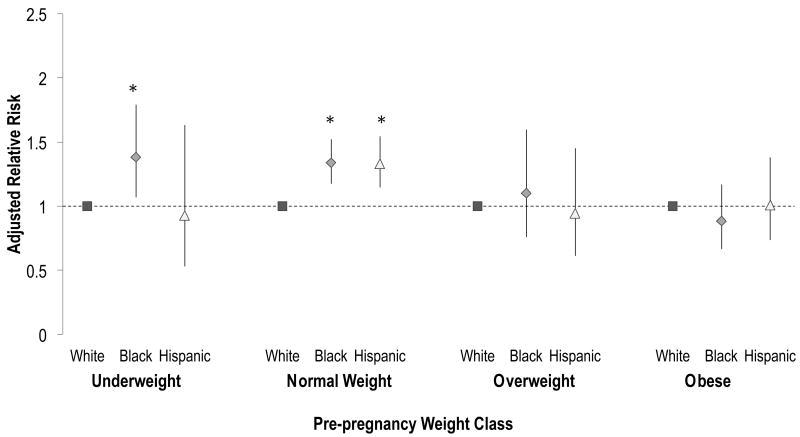

Racial/ethnic differences in risk of inadequate GWG varied by pre-pregnancy BMI (Wald p=0.08). Thus, we report relative risks for racial differences in inadequate GWG by pre-pregnancy weight class category. For normal weight women, the risk of inadequate GWG was higher for Blacks (RR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.18, 1.52; Figure 2) and Hispanics (RR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.15, 1.54; Figure 2) than Whites. Among underweight women, Blacks also had a significantly higher risk (RR:1.38; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.79) of inadequate GWG than Whites; Hispanic women's risk did not significantly differ from Whites. For overweight and obese women, risk of inadequate GWG did not vary by race/ethnicity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Racial Differences in Inadequate Gestational Weight Gain by Pre-pregnancy Weight Class (births n= 3788; moms n= 2440)a.

aStratum specific point estimates for each weight class were derived from the full adjusted model including interaction terms using the lincom command in Stata 11.1. Comparisons of Black or Hispanic women are to White women in that weight class. Point estimates for all strata are shown for completeness, but interaction terms were only significant for the obese pre-pregnancy weight class (Black: p=0.01; Hispanic: p=0.10). P-values for interaction terms for underweight and overweight Black women were p=0.81 and p=0.32, respectively. P-values for interaction terms for underweight and overweight Hispanic women were p=0.22 and p 0.14, respectively *Denotes significant associations at the p≤0.05 level

Excessive GWG

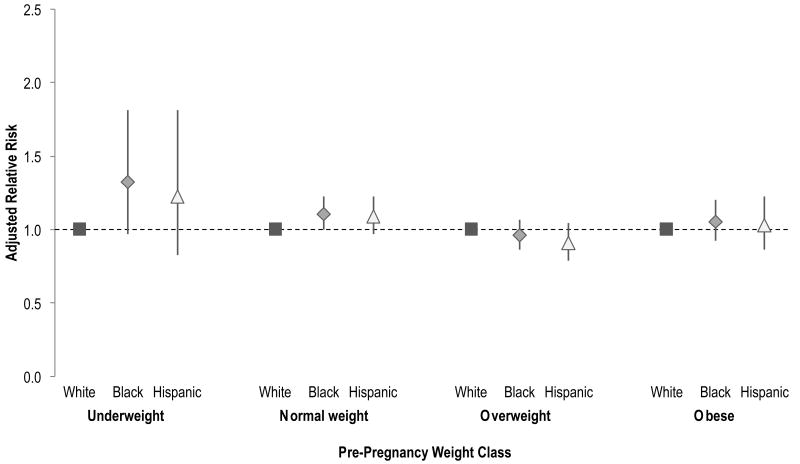

Crude analysis indicated that Black (RR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.20) and Hispanic (RR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.18) women were significantly more likely to gain excessively compared White women, but adjusted risk ratios were attenuated and no longer significant (Black RR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.14; Hispanic RR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.95, 1.12). There was no interaction between race/ethnicity and pre-pregnancy weight class for excessive GWG (Wald p=0.17). Estimates of racial differences in excessive GWG by pre-pregnancy weight class are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Racial Differences in Excessive Gestational Weight Gain by Pre-Pregnancy Weight Class (births n=5128; moms n=3190)a.

aStratum specific point estimates for each weight class were derived from the full adjusted model including interaction terms using the lincom command in Stata 11.1. Comparisons of Black or Hispanic women are to White women in that weight class. Point estimates for all strata are shown for completeness, but interaction, overall, was not significant based on a Wald test (p=0.17)

Sensitivity Analysis

Point estimates after multiple imputation of missing covariates were similar to our complete case results (Appendix Tables A3-A4), but some standard errors differed, affecting statistical significance. Point estimates changed anywhere from 0.1% to 21%. Differences in standard errors are expected as multiply imputed data sets have larger sample sizes and account for uncertainty inherent in the imputation process (39). Overall, Wald tests supported significant interaction for inadequate GWG (Wald p=0.01) and not for excessive GWG (Wald p=0.20). For inadequate GWG, the interaction term for Hispanic underweight women became significant, but the interaction term for Hispanic obese women was no longer significant. Although these differences reflect changes in estimates considered “statistically significant,” the magnitude of changes in p-values were small.

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative, multi-ethnic cohort, racial/ethnic differences in GWG varied by pre-pregnancy weight class. Like others (6,7,9-11,23), we observed racial/ethnic differences in inadequate GWG, independent of sociodemographic, maternal, and pregnancy characteristics. These significant associations were limited to women with pre-pregnancy BMI <25 kg/m2, whereby risk of inadequate GWG was higher in Black and Hispanic compared to White women. We found no evidence of racial/ethnic differences in risk of excessive GWG overall or by BMI subgroups.

Our findings are consistent with three previous studies (9,10,23) that found variation by pre-pregnancy BMI. Hickey et al. (1999) used 1994 Alabama WIC and birth records of 19,017 births and found that odds of inadequate GWG for Black women compared to White women was higher within the non-obese pre-pregnancy weight stratum than for the overall cohort (10). From studying 427 singleton births to adolescents and young adults in New Haven, CT from 2001 to 2004, Gould-Rothberg et al. (2011) found that among normal and overweight women, Black women had lower weight gain compared to their White counterparts, while this was not the case among obese women (9). Fontaine et al. (2012), who analyzed 2760 births to Minneapolis-St. Paul-area women in 2008, similarly found that among normal weight and overweight women, Black women gained less across all trimesters compared to their white counterparts (23). They additionally found that this difference was significant among obese women as well (23). However, each of these studies assessed GWG differently, making direct comparison of subgroup-specific findings across studies difficult. Gould-Rothberg et al. (2011) used a trajectory of gain over pregnancy and into the postpartum period, making it difficult to determine whether weight gained during pregnancy or weight retained after pregnancy were driving results (9). Fontaine et al. (2012) reported race-specific prevalence of inadequate GWG by trimester for each pre-pregnancy weight class, but did not adjust for covariates in overall estimates (23). Hickey et al. (1999) closely reflected our measure of inadequate GWG, but the authors only reported stratum-specific Black-White differences for non-obese (i.e. normal weight and overweight together) women (10). Furthermore, while all studies were racially and ethnically diverse, racial/ethnic subgroups were not all equally balanced. Similar to our population, Fontaine et al. (23) had a population that was majority White (74%), whereas Gould-Rothberg et al. (9) studied a majority Black (59%) population. Hickey et al. (10) was the most evenly balanced between Whites and Blacks, but had no Hispanics. These studies showed similar distributions of pre-pregnancy weight class, although Hickey et al. (10) had a higher prevalence of underweight women and our study had a lower prevalence of pre-pregnancy obesity. Despite these differences, these studies generally supported our findings.

Our findings differed from two studies investigating variation of racial/ethnic differences in inadequate GWG by pre-pregnancy BMI. Both (6,11) tested for interaction between race/ethnicity and numerous characteristics and did not find evidence of variation in racial/ethnic differences in GWG by pre-pregnancy weight class. However, Caulfield et al. (1996), who studied 3870 singleton births to Black and White mothers between 1987-1989, controlled for pregnancy complications that vary in prevalence across racial/ethnic groups and pre-pregnancy weight classes (4). This likely attenuated differences across cross-classified groups. For example, if women with pregnancy complications, like gestational diabetes or preeclampsia, experience increased monitoring by their prenatal care providers, their weight gain may also be more closely monitored and intervened upon. Differences between our findings and those of Pawlak et al. (2013), who analyzed birth certificate data from 2007-2010 on 230,698 births to women in Colorado, are likely explained by their use of “clinically significant” criteria (a 20% change in the odds ratio) and our use of more common, statistical criteria for assessing interaction (11). Additionally, they had a much lower Black population (3.9%) than any other study, likely limiting their power to detect further interaction by pre-pregnancy weight class (11).

Notably, whereas most prior studies focused on Black-White differences, ours also included Hispanics. Of the two studies that considered all three racial/ethnic groups, Gould-Rothberg et al. (2011) found variation of racial/ethnic difference in GWG by pre-pregnancy BMI, while Pawlak et al. (2013) did not. Direct comparison of these findings are limited due to differences in the assessment of weight gain (9) and criteria for significant interaction (11). Future researchers should not only include Hispanic women but also consider ethnic subgroups, since other studies (21,40,41) have found that many birth outcomes vary by Hispanic subgroup (e.g., Puerto Rican).

Our findings are important because the association between low GWG and low birth weight (LBW) and SGA outcomes is more pronounced among underweight and normal weight women (13,42,43). Since LBW affects health across the lifecourse and is more prevalent among Blacks (4,13,28,43-47), these findings that racial/ethnic disparities in inadequate GWG are also most pronounced for normal weight women are of potential concern. However, it is also unclear whether racial differences in SGA or preterm birth vary by pre-pregnancy BMI, since the sparse existing literature has not yet reached a consensus (44,48-54). Future researchers should consider how racial/ethnic disparities in inadequate GWG may contribute to perpetuating existing disparities in LBW outcomes (20,49,55,56). Furthermore, while low GWG can be moderately improved through interventions like energy supplementation (57), the positive impact of increasing GWG through such interventions for reducing LBW and SGA outcomes is tenuous (57,58). However, weight gains that meet or exceed IOM recommendations may increase infant birth weight (55,59). Future research should examine these possible pathways to fully understand how best to intervene through GWG to improve LBW and SGA outcomes.

Psychosocial stress is a possible mechanism for differences in racial disparities in GWG by pre-pregnancy weight . Minority populations are exposed to more stress over the life course (60), and stress, due to things such as financial strain, emotional stressors, and traumatic events, is in turn associated with lower GWG (30,61,62), but only among underweight and normal weight women (62). Investigating the relationship between race, pre-pregnancy BMI, and inadequate GWG in conjunction with structural and environmental stressors may be an important next step to address racial disparities in GWG and associated adverse maternal and child health outcomes.

Excessive GWG is currently more prevalent than adequate GWG (5). Consistent with others (6,8,9,11,23), we found no evidence of racial/ethnic disparities, even after assessing differences by pre-pregnancy weight. This suggests that excessive GWG needs to be addressed in all women, however, there is evidence that, key barriers to and perceptions of GWG vary by race/ethnicity (63-65). In particular, Black (64,65) and Hispanic (66,67) women are more influenced by familial perceptions of weight gain and lack of provider advice. Minority women also report less physical activity during pregnancy due to less social support (63,64,68) and fear of hurting the baby (64,67). Additionally, women with lower acculturation rely more heavily on family members' recommendations (63,66), who advise gaining more weight than health care providers recommend. We recommend developing more culturally sensitive interventions that acknowledge these types of barriers to help women achieve healthy weight gains during pregnancy.

Our study had some limitations. First, all information was self-reported. Self-reported pre-pregnancy weight by pregnant women is highly correlated with medically recorded weight, but may be biased depending on amount of GWG and sociodemographic characteristics, especially when women are asked to recall this weight years after their pregnancy (32,69-73). Nonetheless, virtually all published studies depend on self-reported pre-pregnancy weight. Misreporting error is generally small and trends toward underreporting preganancy-related weight, although this also varied by maternal characteristics (69,74). The literature suggests 30-40% of women may be misclassified when grouped by IOM GWG recommendations (although this varies depending on population and subgroup), and while this misclassification does not affect associations between GWG and birth outcomes (32,69), the impact on our particular study is unknown. Future studies using measured weight are needed to address this limitation and confirm our findings.

The IOM GWG categories are relevant only for women delivering at term. Since more than 10% of women in NLSY delivered before 37 weeks, and gestational age differs by race-ethnicity, we used a measure of GWG adequacy to assign an appropriate category of GWG according to both BMI and gestational age. This method does not perfectly account for the non-linear relationship between length of gestation and GWG when modeling associations with birth outcomes affected by gestational age, (75) and a new approach has been published, though only for normal weight women. (76) Nonetheless, using weight gain adequacy reduces misclassification in GWG due to length of gestation, which is a strength of our study.

While the NLSY79 collected a wide array of information about pregnancies occurring to participants, they did not include a number of factors on complications experienced during pregnancy that may impact GWG, such as gestational diabetes and edema. This may be a source of unmeasured confounding that we were unable to address in the current study.

Finally, interaction analyses are widely known to have limited power (77). We thus set a more conservative type I error threshold, but we may still have been underpowered, particularly in our underweight (n=185) and obese groups (n=137), due to small sample size. While we still were able to detect variation of racial/ethnic differences in inadequate GWG among obese women, future analyses should aim to include more underweight women so that this relationship can be further studied.

Importantly, our study had many strengths. First, the study was longitudinal in nature and included virtually all births to women over their lifetime, which may better characterize their GWG experience. Given that many individual characteristics, such as marital status and income, can change over time, the inclusion of multiple pregnancies for women allowed us to capture these changes. Second, our data are from a large, nationally representative population of the women. This makes our findings generalizable to the external population of US women who were 14-22 in 1979, although it may be less generalizable to current populations in which prevalence of pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity have increased as well as the number of minority women of childbearing age (4). Finally, the NLSY79 includes a comprehensive set of SES variables beyond single indicators of education and income. This is particularly important when studying racial/ethnic disparities because, beyond the known entrenched racial/ethnic differences in socioeconomic environments, historical trends that shaped and constrained the social and economic mobility of individuals' parents continue to strongly impact the socioeconomic status that the individual is able to achieve (78).

In summary, we found racial/ethnic differences in inadequate GWG among normal and underweight women. Future studies are required in large, diverse populations with measured weight and a wider array of covariates to confirm this finding and to investigate underlying mechanisms. Taking nuances in racial/ethnic disparities into account, particularly for inadequate GWG, may become particularly relevant in creating culturally relevant interventions to promote adequate GWG and potentially improving short- and long-term health outcomes of both mothers and their infants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health (Grant number R01MD006014) and the University of California Chancellor's Fellowship for Graduate Study.

Table A1. Prevalence of Missing Values for Analytic Variables.

| Variable Name | Percent Missing (%) |

|---|---|

| Gestational Weight Gain | 2.8 |

| Prepregnancy Weight | 2.1 |

| Education | 3.9 |

| Income | 14.4 |

| Employment | 2.3 |

| Marital Status | 3.7 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 0.4 |

Table A2. Descriprive Statistics for Analytic Variables Between the Complete Case and Full Study Sample.

| Weighted Percentages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| In complete case (births=6849; mothers=3835) | Excluded from Complete Case (births=1994; mothers=834) | p-value | ||

| Race(%)a | <0.001 | |||

| White | 72.84 | 86.23 | ||

| Black | 20.98 | 9.15 | ||

| Hispanic | 6.18 | 4.62 | ||

| GWG (mean (SD)) | 14.50 (7.27) | 14.10 (6.58) | 0.8 | |

| GWG Ratio (mean (SD)) | 1.26 (0.76) | 1.27 (0.73) | 0.06 | |

| GWG Adequacy (%) | 0.06 | |||

| Inadequate | 26.04 | 23.07 | ||

| Adequate | 28.53 | 32.5 | ||

| Excessive | 45.43 | 44.43 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy Weight (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight | 11.39 | 7.74 | ||

| Normal | 66.89 | 66.77 | ||

| Overweight | 14.64 | 16.35 | ||

| Obese | 7.09 | 9.14 | ||

| Parity (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 47.35 | 42.31 | ||

| 1 | 30.13 | 35.38 | ||

| 2 | 14.88 | 15.18 | ||

| 3 | 5.19 | 4.95 | ||

| 4 | 1.37 | 1.47 | ||

| 5 | 0.86 | 0.38 | ||

| 6 | 0.1 | 0.15 | ||

| 7 | 0.09 | 0.12 | ||

| 8 | 0.00 | 0.04 | ||

| 9 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| Education (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Less than high school | 34.03 | 14 | ||

| High school | 53.73 | 66.38 | ||

| College | 12.24 | 19.62 | ||

| Participant's Mother's Education (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Less than high school | 43.89 | 29.84 | ||

| High school | 49.56 | 60.75 | ||

| College | 6.55 | 9.42 | ||

| Equivalized Income (mean (SD))b | 9.68 (1.31) | 9.83 (1.18) | 0.003 | |

| Household Income (y2000 dollars; mean (SD)) |

16955.93 | 44872.73 | <0.001 | |

| Family size (mean (SD)) | 3.74 | 3.27 | <0.001 | |

| Employment (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Unemployed | 64.90 | 30.09 | ||

| Part-time | 17.38 | 30.59 | ||

| Full-time | 17.72 | 39.32 | ||

| Married (%) | 60.55 | 78.68 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking During Pregnancy (%) | 27.84 | 28.43 | 0.44 | |

| Gestational Age (mean (SD)) | 38.60 (2.23) | 38.63 (2.02) | 0.83 | |

| Child's Birth Year (mean (SD)) | 1987 (5.75) | 1988 (5.38) | <0.001 | |

| Mother's Age at Birth (mean (SD)) | 25.52 (5.87) | 26.74 (5.12) | <0.001 | |

N represent mothers in the data set (N=3835)

Equivalized income was calcluated to adjust for family size. For a family of 4 in year 2000 (the year to which all incomes in our data set are standardized to) our mean equivalized income of 9.68 corresponds to an aggregate houshold income of $27,086.

Table A3. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Inadequate Gestational Weight Gain (2009 IOM Recommendations): Complete Case Compared to Multiple Imputationa.

| Model 4: Crude Association | Model 5: Adjusted Main Effectsb | Model 6: Adjusted Effect Modificationb | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | |||||||

| RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | |

| Black | 1.41 (1.28, 1.55) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.28, 1.52) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.13, 1.41) | <0. 001 | 1.25 (1.13, 1.39) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.18, 1.52) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.20, 1.51) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.27 (1.13, 1.43) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.10, 1.36) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.07, 1.40) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.02, 1.31) | 0.02 | 1.33 (1.15, 1.54) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.10, 1.44) | <0.01 |

| Wald Test: p-value=0.08 | Wald Test: p-value=0.01 | |||||||||||

| Underweight† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 1.433 (1.07, 1.92) | 0.02 | 1.359 (1.08, 1.71) | 0.01 | 1.38 (1.11, 1.72) | 0.01 | 1.25 (0.98, 1.59) | 0.07 | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.715 (0.38, 1.35) | 0.30 | 0.846 (0.52, 1.39) | 0.51 | 1.10 (0.81, 1.50) | 0.80 | 1.20 (0.49, 1.35) | 0.43 | ||||

| Normal Weight† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 1.559 (1.37, 1.78) | <0.001 | 1.509 (1.37, 1.67) | <0.001 | - - | - | - - | - | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.41 (1.19, 1.67) | <0.001 | 1.354 (1.20, 1.53) | <0.001 | - - | - | - - | - | ||||

| Overweight† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 1.30 (0.85, 1.99) | 0.22 | 1.342 (0.99, 1.82) | 0.06 | 0.88 (0.70, 1.12) | 0.61 | 0.82 (0.87, 1.66) | 0.27 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.313 (0.83, 2.09) | 0.25 | 1.028 (0.70, 1.51) | 0.89 | 0.93 (0.58, 1.49) | 0.79 | 0.82 (0.61, 1.36) | 0.64 | ||||

| Obese† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.933 (0.64, 1.36) | 0.72 | 0.90 (0.70, 1.15) | 0.40 | 0.94 (0.66, 1.36) | 0.39 | 0.91 (0.64, 1.07) | 0.14 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.20 (0.78, 1.85) | 0.41 | 1.039 (0.78, 1.38) | 0.79 | 1.01 (0.77, 1.31) | 0.96 | 1.01 (0.75, 1.35) | 0.95 | ||||

Complete Cases Sample: 3788 births to 2440 mothers; Multiple Imputation Sample: 4615 births to 2861 mothers

Models adjusted for pre-pregnancy weight class, parity, participant's education, participant's mother's education, equivalized income, employment, marital status, smoking during pregnancy, child's birth year, and mother's age at birth.

Point estimates for racial/ethnic differences within strata of pre-pregnancy weight

Table A4. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Excessive Gestational Weight Gain (2009 IOM Recommendations): Complete Case Compared to Multiple Imputationa.

| Model 7: Crude Association | Model 8: Adjusted Main Effectsb | Model 9: Adjusted Effect Modificationb | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | |||||||

| RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | RR (95%CI) |

p-value | |

| Black | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | <0.01 | 1.06 (0.99, 1.14) | 0.11 | 1.05 (0.98, 1.12) | 0.18 | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | 0.05 | 1.09 (0.99, 1.20) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic | 1.09 (1.01, 1.18) | 0.04 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.16) | 0.02 | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | 0.51 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.11) | 0.55 | 1.09 (0.97, 1.23) | 0.16 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) | 0.15 |

| Wald Test: p-value=0.17 | Wald Test: p-value=0.02 | |||||||||||

| Underweight† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 1.162 (0.79, 1.70) | 0.44 | 1.229 (0.95, 1.59) | 0.12 | 1.32 (0.97, 1.81) | 0.08 | 1.22 (0.96, 1.57) | 0.11 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.435 (0.92, 2.23) | 0.11 | 1.039 (0.71, 1.53) | 0.85 | 1.22 (0.82, 1.81) | 0.32 | 0.96 (0.67, 1.44) | 0.93 | ||||

| Normal Weight† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.929 (0.83, 1.04) | 0.19 | 1.088 (1.00, 1.18) | 0.05 | - - | - | - - | - | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.993 (0.87, 1.14) | 0.92 | 1.101 (1.00, 1.21) | 0.06 | - - | - | - - | - | ||||

| Overweight† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 0.935 (0.84, 1.05) | 0.24 | 0.993 (0.91, 1.08) | 0.87 | 0.96 (0.87, 1.07) | 0.45 | 1.02 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.45 | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.861 (0.74, 1.00) | 0.04 | 0.93 (0.83, 1.04) | 0.21 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.04) | 0.16 | 0.83 (0.81, 1.04) | 0.19 | ||||

| Obese† | ||||||||||||

| Black | 1.062 (0.90, 1.26) | 0.48 | 0.994 (0.89, 1.11) | 0.92 | 1.05 (0.93, 1.20) | 0.42 | 0.92 (0.90, 1.16) | 0.75 | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.944 (0.76, 1.18) | 0.61 | 1.024 (0.90, 1.17) | 0.73 | 1.03 (0.86, 1.22) | 0.75 | 1.05 (0.90, 1.23) | 0.53 | ||||

Complete Cases Sample: 5128 births to 3190 mothers; Multiple Imputation Sample: 6182 births to 3704 mothers

Models adjusted for pre-pregnancy weight class, parity, participant's education, participant's mother's education, equivalized income, employment, marital status, smoking during pregnancy, child's birth year, and mother's age at birth.

Point estimates for racial/ethnic differences within strata of pre-pregnancy weight

Contributor Information

Irene Headen, Email: iheaden@berkeley.edu.

Mahasin S. Mujahid, Email: mmujahid@berkeley.edu.

Alison K. Cohen, Email: akcohen@berkeley.edu.

David H. Rehkopf, Email: drehkopf@stanford.edu.

Barbara Abrams, Email: babrams@berkeley.edu.

References

- 1.Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N. Closing the Black-White tap in birth outcomes: A Life-Course Approach. Ethn Dis. 2010;20:S2.62–S2.76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braveman P. Black–White disparities in birth outcomes: Is racism-related stress a missing piece of the puzzle? In: Lemelle AJ, Reed W, Taylor S, editors. Handbook of African American Health: Social and Behavioral Interventions. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2011. pp. 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon B, Rifas-Shiman SL, James-Todd T, et al. Maternal experiences of racial discrimination and child weight status in the first 3 years of life. J Devel Orig Health Dis. 2012;3(06):433–441. doi: 10.1017/S2040174412000384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, editors. Weight gain during pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Activity D.O.N.A.P., editor. Pediatric and Pregnancy Nutrition Surveillance System. 2013. Nation: Summary of Trends in Maternal Health Indicators by Race/Ethnicity. Table 20D. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caulfield LE, Witter FR, Stoltzfus RJ. Determinants of gestational weight gain outside the recommended ranges among black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(5):760–766. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Bish CL, D'Angelo D. Gestational weight gain by body mass index among US women delivering live births, 2004-2005: fueling future obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:271.e1–271.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuebe AM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Associations of diet and physical activity during pregnancy with risk for excessive gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:58.e1–58.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould Rothberg BE, Magriples U, Kershaw TS, Rising SS, Ickovics JR. Gestational weight gain and subsequent postpartum weight loss among young, low-income, ethnic minority women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:52.e1–52.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickey CA, Kreauter M, Bronstein J, et al. Low Prenatal Weight Gain Among Adult WIC Participants Delivering Term Singleton Infants: Variation by Maternal and Program Participation Characteristics. Matern Child Health J. 1999;3(3):129–140. doi: 10.1023/a:1022341821346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawlak MT, Alvarez BT, Jones DM, Lezotte DC. The effect of race/ethnicity on gestational weight gain. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9886-5. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poston L. Maternal obesity, gestational weight gain and diet as determinants of offspring long term health. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(5):627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margerison-Zilko CE, Rehkopf D, Abrams B. Association of maternal gestational weight gain with short- and long-term maternal and child health outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):574.e1–574.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Belfort MB, Hammitt JK, Gillman MW. Associations of gestational weight gain with short- and longer-term maternal and child health outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):173–180. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deardorff J, Berry-Millett R, Rehkopf D, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and age at menarche in daughters. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(8):1391–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1139-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser A, Tilling K, Macdonald-Wallis C, et al. Associations of gestational weight gain with maternal body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure measured 16 y after pregnancy: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(6):1285–1292. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.008326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mamun AA, Callaway LK, O'Callaghan MJ, et al. Associations of maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and excess pregnancy weight gains with adverse pregnancy outcomes and length of hospital stay. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen AK, Chaffee BW, Rehkopf DH, Coyle JR, Abrams B. Excessive gestational weight gain over multiple pregnancies and the prevalence of obesity at age 40. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38(5):714–718. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Headen IE, Davis EM, Mujahid MS, Abrams B. Racial-ethnic differences in pregnancy-related weight. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:83–94. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stotland NE, Caughey AB, Lahiff M, et al. Weight gain and spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(6):1448–1455. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000247175.63481.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington E. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontaine PL, Hellerstedt WL, Dayman CE, Wall MM, Sherwood NE. Evaluating body mass index-specific trimester weight gain recommendations: Differences between Black and White women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012;57(4):327–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siega-Riz AM, Hobel C. Predictors of poor maternal weight gain from baseline anthropometric, psychosocial, and demographic information in a Hispanic population. J am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(11):1264–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodnar LM, Hutcheon JA, Platt RW, et al. Should gestational weight gain recommendations be tailored by maternal characteristics? Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(2):136–146. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keppel KG, Taffel SM. Pregnancy-related weight gain and retention: Implications of the 1990 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1100–1103. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hickey CA. Sociocultural and behavioral influences on weight gain during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(suppl):1364S–70S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1364s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burkhauser RV, Cawley J. Beyond BMI: The value of more accurate measures of fatness and obesity in social science research. J Health Econ. 2008;27:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClure CK, Bodnar LM, Ness R, Catov JM. Accuracy of Maternal Recall of Gestational Weight Gain 4 to 12 Years After Delivery. Obesity. 2011;19(5):1047–1063. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens-Simon C, Roghmann KJ, McAnarney ER. Relationship of self-reported prepregnant weight and weight gain during pregnancy to maternal body habitus and age. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. Disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research. JAMA. 2005;294:2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehkopf DH, Krieger N, Coull B, Berkman L. Biologic risk markers for coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2010;21:38–46. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30b89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenland S. Interactions in Epidemiology: Relevance, Identification, and Estimation. Epidemiology. 2009;20(1):14–17. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318193e7b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: An overview and some applications. Stat Med. 1991;10:585–598. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sparks PJ. One size does not fit all: An examination of low birthweight disparities among a diverse set of racial/ethnic groups. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(6):769–779. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0476-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Pekow P, et al. Predictors of excessive and inadequate gestational weight gain in Hispanic women. Obesity. 2008;16(7):1657–1666. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J, Liao G, McDonald SD. Maternal underweight and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):65–101. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siega-Riz AM, Viswanathan M, Moos MK, et al. A systematic review of outcomes of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations: Birthweight, fetal growth, and postpartum weight retention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(4):339.e1–339.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savitz DA, Stein CR, Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH. Gestational weight gain and birth outcome in relation to prepregnancy body mass index and ethnicity. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caulfield LE, Stoltzfus RJ, Witter FR. Implications of the Institute of Medicine weight gain recommendations for preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes in Black and White women. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1168–1174. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.8.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schieve LA, Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS. An empiric evaluation of the institute of medicine's pregnancy weight gain guidelines by race. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:878–884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hickey CA, McNeal SF, Menefee L, Ivey S. Prenatal weight gain within upper and lower recommended ranges: Effect on birth weight of black and white infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:489–494. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masho SW, Bishop DL, Munn M. Pre-pregnancy BMI and weight gain: Where is the tipping point for preterm birth? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hunt KJ, Alanis MC, Johnson ER, Mayorga ME, Korte JE. Maternal pre-pregnancy weight and gestational weight gain and their association with birthweight with a focus on racial differences. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(1):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0950-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aly H, Hammad T, Nada A, Bathgate S, El-Mohandes A. Maternal obesity, associated complications and risk of prematurity. J Perinatol. 2009;30(7):447–451. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salihu HM, Luke S, Alio AP, et al. The superobese mother and ethnic disparities in preterm birth. J Natl Med Assocn. 2009;101(11):1125–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simhan HN. Prepregnancy body mass index, vaginal inflammation, and the racial disparity in preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(5):459–466. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torloni MR, Fortunato SJ, Betrán AP, et al. Ethnic disparity in spontaneous preterm birth and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;285(4):959–966. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Jongh BE, Paul DA, Hoffman M, Locke R. Effects of pre-pregnancy obesity, race/ethnicity and prematurity. Matern Child Health J. 2013;18(3):511–517. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Misra VK, Hobel C, Sing CF. The effects of maternal weight gain patterns on term birth weight in African-American women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(8):842–849. doi: 10.3109/14767050903387037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Heffner LJ, Rosenberg L. Prepregnancy body size, gestational weight gain, and risk of preterm birth in African-American women. Epidemiology. 2010;21(2):243–252. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181cb61a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ota E, Tobe-Gai R, Mori R, Farrar D. Antenatal dietary advice and supplementation to increase energy and protein intake (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):1–59. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000032.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Energy and protein intake in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):1–78. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hickey CA, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Kohatsu J, Hoffman HJ. Prenatal weight gain, term birth weight and fetal growth retardation among high-risk multiparous black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis EM, Stange KC, Horwitz RI. Childbearing, stress and obesity disparities in women: A public health perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(1):109–118. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0712-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Webb JB, Siega-Riz AM, Dole N. Psychosocial determinants of adequacy of gestational weight gain. Obesity. 2008;17:300–309. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu P, Huang W, Hao JH, et al. Time-specific effect of prenatal stressful life events on gestational weight gain. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122(3):207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evenson KR, Moos MK, Carrier K, Siega-Riz AM. Perceived barriers to physical activity among pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2008;13(3):364–375. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0359-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodrich K, Cregger M, Wilcox S, Liu J. A qualitative study of factors affecting pregnancy weight gain in African American women. Matern Child Health J. 2012;17(3):432–440. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1011-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herring SJ, Henry TQ, Klotz AA, Foster GD, Whitaker RC. Perceptions of low-income African-American mothers about excessive gestational weight gain. Matern Child Health J. 2011;16(9):1837–1843. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0930-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tovar A, Chasan-Taber L, Bermudez OI, Hyatt RR, Must A. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding weight gain during pregnancy among Hispanic women. Matern Child Health J. 2009;14(6):938–949. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0524-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marquez DX, Bustamante EE, Bock BC, et al. Perspectives of Latina and non-Latina White women on barriers and facilitators to exercise in pregnancy. Women & Health. 2009;49(6-7):505–521. doi: 10.1080/03630240903427114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thornton PL, Kieffer EC, Salabarría-Peña Y, et al. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: The role of social support. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schieve LA, Perry GS, Cogswell ME, et al. Validity of self-reported pregnancy delivery weight: An analysis of the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(9):947–956. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Biro FM, Wiley-Kroner B, Whitsett D. Perceived and measured weight changes during adolescent pregnancy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1999;12:31–32. doi: 10.1016/S1083-3188(00)86618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tomeo CA, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, et al. Reproducibility and validity of maternal recall of pregnancy-related events. Epidemiology. 1999;10(6):774–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu SM, Nagey DA. Validity of self-reported pregravid weight. Ann Epidemiol. 1992;2(5):715–721. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(92)90016-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stevens-Simon C, McAnarney ER, Coulter MP. How accurately do pregnant adolescents estimate their weight prior to pregnancy? J Adolesc Health Care. 1986;7(4):250–254. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0070(86)80017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunt SC, Daines MM, Adams TD, Heath EM, Williams RR. Pregnancy weight retention in morbid obesity. Obes Res. 1995;3(2):121–130. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Joseph KS, et al. The bias in current measures of gestational weight gain. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(2):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hutcheon JA, Platt RW, Abrams B, et al. A weight-gain-for-gestational-age z score chart for the assessment of maternal weight gain in pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):1062–1067. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.051706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Selvin S. Statistical Analysis of Epidemiological Data. 3rd. Oxford Univ Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]