A comprehensive health survey released by Statistics Canada in mid June found that more than one million Canadians have looked for, but have not been able to find, a family physician.

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), conducted in 2003, contains the results of responses from 135 000 Canadians aged 12 and older who were asked more than 1000 questions.

A total of 14% of Canadians, or 3.6 million people, are without an FP. Of that number, 1.2 million have searched unsuccessfully for an FP. “It's a significant number,” said Marc Hamel, a senior analyst at Statistics Canada and the survey's chief. The other 2.4 million Canadians have not been looking.

More than twice as many men as women indicated that they had not looked for a doctor. Most of those who had not looked were in the 20–34 age group.

“We see there are differences between those who have a doctor and those who don't,” said Hamel. “For instance, women are less likely to have a mammogram or Pap smear test if they don't have a regular physician. We also found people were less likely to have their blood pressure checked when they didn't have a regular doctor.”

Although it seems to be harder to find an FP in rural areas than urban centres (5.5% of rural dwellers reported difficulties v. 4.5% of urbanites), Howard points out that the discrepancy is not as great as most people believe.

“You can easily make the hypothesis that if there is a shortage of physicians, and if people have trouble finding a doctor, that it will be more predominant in rural areas, and the data do not seem to indicate that,” Hamel told CMAJ.

In 1994, 63.1% of Canadians considered themselves to be in excellent health. That figure fell to 58.4% in 2003. Obesity and overweight affect nearly half the population: 14.9% of adult Canadians considered themselves obese, and 33.3% said they were overweight. More Canadians are butting out, according to the survey. In 1994, 29.3% of the population smoked, and this figure dropped to 22.9% in 2003.

One new demographic variable that the survey included was sexual orientation. Nearly twice as many homosexual respondents (21.8%) had unmet health care needs compared with their heterosexual counterparts (12.7%). — Louise Gagnon, Ottawa

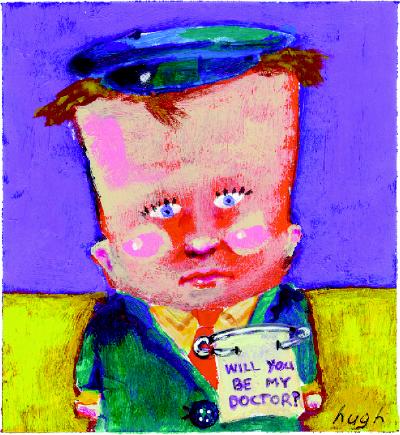

Figure.

Photo by: Hugh Malcolm