Abstract

The antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of the essential oils from Thymbra capitata and Thymus species grown in Portugal were evaluated. Thymbra and Thymus essential oils were grouped into two clusters: Cluster I in which carvacrol, thymol, p-cymene, α-terpineol, and γ-terpinene dominated and Cluster II in which thymol and carvacrol were absent and the main constituent was linalool. The ability for scavenging ABTS•+ and peroxyl free radicals as well as for preventing the growth of THP-1 leukemia cells was better in essential oils with the highest contents of thymol and carvacrol. These results show the importance of these two terpene-phenolic compounds as antioxidants and cytotoxic agents against THP-1 cells.

1. Introduction

Thymbra capitata and several Thymus species grown in Portugal produce essential oils (EOs) of interest for the food and fragrance industries and are also of medicinal value. Opposite to essential oils of T. capitata, characterized by a great chemical homogeneity with high carvacrol relative amounts, Thymus EOs show many chemotypes [1].

Although this chemical polymorphism may represent a problem for the required efficacy constancy of an EO, the EOs isolated from T. capitata and from different Portuguese Thymus species have all been shown to possess anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiparasitical, insecticidal, and nematicidal activity, among other biological properties [1–10].

Earlier studies have shown the antioxidant potential of these EOs, but no previous report addressed the antiproliferative properties of the EOs from T. capitata and Thymus species grown in Portugal. For this reason, the main goal of the present work was to determine the antiproliferative activity of these EOs on the THP-1 leukemia cell line. Also, the in vitro antioxidant activity was evaluated with methodologies based on distinct mechanisms: one based on electron transfer and the other on hydrogen atom transfer (Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) and Oxygen Radical Antioxidant Capacity (ORAC), resp.).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The aerial parts of Portuguese Thymbra and Thymus species, from collective or individual samples, were collected from wild-grown plants in the mainland of Portugal and in the Azores archipelago (Portugal). Plant material was stored at −20°C until extraction. In total, EOs isolated from 9 plant samples were evaluated for chemical composition and biological activity (Table 1). Certified voucher specimens have been deposited at the Herbarium of the Botanical Garden of Lisbon University (Lisbon, Portugal).

Table 1.

Plant species scientific names, arranged according to alphabetic order, collection site, and corresponding code.

| Plant species | Collection site | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Thymbra capitata (L.) Cav. | Gambelas, mainland Portugal | Tc |

| Thymus caespititius Brot. | Faial, Azores, Portugal | Thc_F |

| Thymus caespititius Brot. | Pico, Azores, Portugal | Thc_P |

| Thymus caespititius Brot. | Terceira, Azores, Portugal | Thc_T |

| Thymus caespititius Brot. | Gerês, mainland Portugal | Thc_G |

| Thymus caespititius Brot. | Praia do Cortiço, mainland Portugal | Thc_PC |

| Thymus mastichina (L.) L. | Vila Chã, mainland Portugal | Thm_VC |

| Thymus pulegioides L. | Serra da Nogueira, mainland Portugal | Thp_SN |

| Thymus villosus subsp. lusitanicus (Boiss.) Cout. | Óbidos, mainland Portugal | Thvl_O |

2.2. Isolation and Chemical Analysis of the EOs

Essential oils were isolated from fresh plant material by hydrodistillation for 3 h, using a Clevenger-type apparatus, according to the European Pharmacopoeia [11], and analyzed by gas chromatography (GC), for component quantification, and gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for component identification, as detailed in Barbosa et al. [2]. Gas chromatographic analyses were performed using a Perkin Elmer Autosystem XL gas chromatograph (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA) equipped with two flame ionization detectors (FIDs), a data handling system, and a vaporizing injector port into which two columns of different polarities were installed: a DB-1 fused-silica column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 μm; J&W Scientific Inc., Rancho Cordova, CA, USA) and a DB-17HT fused-silica column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.15 μm; J&W Scientific Inc.). Oven temperature was programmed to increase from 45 to 175°C, in 3°C/min increments, and then up to 300°C in 15°C/min increments and finally held isothermal for 10 min. Gas chromatographic settings were as follows: injector and detectors temperatures, 280°C and 300°C, respectively; carrier gas, hydrogen, adjusted to a linear velocity of 30 cm/s. The samples were injected using a split sampling technique, ratio 1 : 50. The volume of injection was 0.1 μL of a pentane-oil solution (1 : 1). The percentage composition of the oils was computed by the normalization method from the GC peak areas, calculated as a mean value of two injections from each oil, without response factors. The GC-MS unit consisted of a Perkin Elmer Autosystem XL gas chromatograph, equipped with DB-1 fused-silica column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 μm; J&W Scientific, Inc.) interfaced with Perkin-Elmer Turbomass mass spectrometer (software version 4.1, Perkin Elmer). GC-MS settings were as follows: injector and oven temperatures, as above; transfer line temperature, 280°C; ion source temperature, 220°C; carrier gas, helium, adjusted to a linear velocity of 30 cm/s; split ratio, 1 : 40; ionization energy, 70 eV; scan range, 40–300 u; scan time, 1 s. The identity of the components was assigned by comparison of their retention indices relative to C9–C21 n-alkane indices, and GC-MS spectra from a laboratory made library based upon the analyses of reference oils, laboratory-synthesized components, and commercial available standards. The percentage composition of the isolated EOs was used to determine the relationship between the different samples by cluster analysis using NTSYS, and the degree of correlation was graded as very high (0.9-1), high (0.7–0.89), moderate (0.4–0.69), low (0.2–0.39), and very low (<0.2), as detailed in Faria et al. [12].

2.3. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.1. ABTS•+ Free Radical Scavenging Activity

The determination of ABTS•+ radical scavenging was carried out as described in Antunes et al. [13]. The absorbance was monitored spectrophotometrically at 735 nm for 6 min with a Shimadzu spectrophotometer 160-UV. The antioxidant activity of each sample was calculated as scavenging effect % (IA%) = (1 − A f/A 0) × 100, where A 0 is absorbance of the control and A f the absorbance in the presence of the sample. The values were compared with the curve for several Trolox concentrations and the values given as mM Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity.

2.3.2. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) for EOs

Fluorescein (FL) was the fluorescent probe used in the ORAC method, as described by Ou et al. [14]. EOs samples were diluted 1000 times in acetone before analysis. The equipment used was a Tecan Infinite M200 Microplate Reader. ORAC values were calculated according to [15]. Briefly, the net area under the curve (AUC) of the standards and samples was calculated. The standard curve was obtained by plotting Trolox concentrations against the average net AUC of the three measurements for each concentration. Final ORAC values were calculated using the regression equation between Trolox concentration and the net AUC and were expressed as μmol Trolox/g EO. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

2.4. Antiproliferative Activity

2.4.1. Cell Culture

THP-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum, 1% (v/v) nonessential amino acids, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.4.2. Antiproliferative Activity Evaluation

The growth-inhibitory effect of EOs was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay adopted from Mosmann [16]. THP-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plate at 5 · 103 cells/well and exposed to different concentrations of EOs (10–500 μg/mL) for 1 and 4 days. All test substances were dissolved in dimethyl-sulphoxide (DMSO). The solvent concentration in the incubation medium never exceeded 0.5%. Control cultures received the equivalent concentration of DMSO. After treatment, cells were incubated for 1 h in the usual culture conditions after addition of the same volume of medium containing MTT (2 mg/mL). After this incubation, 150 μL HCl (0.1 M) in isopropanol was added to dissolve the blue formazan crystals formed by reduction of MTT. Absorbance at 570 nm using a background reference wavelength of 630 nm was measured using a dual-wavelength Multiskan Spectrum (Thermo) plate reader. The mean absorbance values for the negative control (DMSO treated cells) were standardized as 100% absorbance (i.e., no growth inhibition) and results were displayed as absorbance (% of control) versus essential oil concentration. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20. Tukey's test was used to determine the difference at 5% significance level. Paired Student's t-test was used in some tests to determine differences at 5% significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of the EOs

The identified components in the 9 EOs isolated from Thymbra and Thymus species, from mainland Portugal and Azores islands, are listed in Table 2 in their elution order on the DB-1 GC column, arranged according to the degree of correlation obtained after agglomerative cluster analysis based on the EOs chemical composition.

Table 2.

Percentage composition of the essential oils isolated from the aerial parts of Thymbra (Tc) and Thymus (Th) Portuguese species evaluated. Samples arranged according to the degree of correlation obtained after agglomerative cluster analysis based on the essential oils' chemical composition. For abbreviations and cluster analysis see Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively.

| Components | RI | I | II | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | Ib | Ic | Id | |||||||

| Tc | Thc_F | Thc_P | Thp_SN | Thc_T | Thm_VC | Thc_G | Thc_PC | Thvl_O | ||

| Tricyclene | 921 | 0.1 | t | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||

| α-Thujene | 924 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| α-Pinene | 930 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Camphene | 938 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Thuja-2,4(10)-diene | 940 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | t | ||||

| Sabinene | 958 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 961 | 0.4 | t | t | 0.4 | t | 0.4 | 0.3 | t | |

| 3-Octanone | 961 | 1.9 | ||||||||

| β-Pinene | 963 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |

| Dehydro-1,8-cineole | 973 | t | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |||

| 2-Pentyl furan | 973 | t | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||

| 3-Octanol | 974 | t | 1.0 | t | t | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||

| β-Myrcene | 975 | 2.5 | 1.0 | t | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | ||

| α-Phellandrene | 995 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| δ-3-Carene | 1000 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | 0.1 | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| α-Terpinene | 1002 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| p-Cymene | 1003 | 8.8 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 13.5 | 9.7 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 3.0 |

| 1,8-Cineole | 1005 | 1.5 | 47.4 | 6.3 | ||||||

| β-Phellandrene | 1005 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | |||

| Limonene | 1009 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.6 | t |

| cis-β-Ocimene | 1017 | t | t | t | t | t | t | |||

| trans-β-Ocimene | 1027 | 0.1 | t | t | 0.2 | t | 0.7 | |||

| γ-Terpinene | 1035 | 5.9 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 10.6 | 6.0 | 7.3 | 10.6 | 4.1 | 0.3 |

| trans-Sabinene hydrate | 1037 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | t | 0.1 | ||

| cis-Linalool oxide | 1045 | t | 0.9 | |||||||

| Fenchone | 1050 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| trans-Linalool oxide | 1059 | 0.8 | ||||||||

| p-Cymenene | 1059 | t | ||||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl styrene | 1059 | t | t | 0.6 | t | |||||

| Terpinolene | 1064 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| cis-Sabinene hydrate | 1066 | 0.1 | t | t | t | t | t | 0.2 | ||

| Linalool | 1074 | 1.1 | 0.5 | t | 1.6 | t | 0.1 | 65.5 | ||

| Oct-1-en-3-yl acetate | 1086 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | ||||||

| trans-p-2-Menthen-1-ol | 1099 | t | t | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||

| Camphor | 1102 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ||||||

| trans-Pinocarveol | 1106 | t | 0.1 | |||||||

| cis-p-2-Menthen-1-ol | 1110 | t | t | |||||||

| cis-Verbenol | 1110 | t | t | t | t | |||||

| Pinocarvone | 1121 | t | ||||||||

| Nerol oxide | 1127 | t | ||||||||

| p-Mentha-1,5-dien-8-ol∗ | 1134 | 0.9 | ||||||||

| δ-Terpineol | 1134 | 0.7 | 0.4 | |||||||

| Borneol | 1134 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1148 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| p-Cymen-8-ol | 1148 | t | 0.3 | |||||||

| Myrtenal | 1153 | t | ||||||||

| cis-Dihydrocarvone | 1159 | t | ||||||||

| α-Terpineol | 1159 | 0.1 | 9.5 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 35.8 | 43.5 | 6.9 |

| Methyl chavicol | 1163 | t | ||||||||

| Myrtenol | 1168 | t | ||||||||

| trans-Carveol | 1189 | 0.1 | t | t | ||||||

| Bornyl formate | 1199 | 0.1 | t | t | t | 0.1 | ||||

| Nerol | 1206 | 0.8 | ||||||||

| Citronellol | 1207 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Carvone | 1210 | 0.1 | t | |||||||

| Thymol methyl ether | 1210 | t | ||||||||

| Neral | 1210 | 0.2 | ||||||||

| Carvacrol methyl ether | 1224 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | t | 0.2 | 0.4 | |||

| Geraniol | 1236 | t | 32.8 | |||||||

| Geranial | 1240 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |||||||

| trans-Anethole | 1254 | t | ||||||||

| Thymol formate | 1262 | 0.1 | t | |||||||

| Bornyl acetate | 1265 | t | t | t | t | 1.2 | 0.6 | |||

| Thymol | 1275 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 10.3 | 12.0 | 42.2 | 13.7 | t | 0.3 | |

| Carvacrol | 1286 | 71.4 | 50.5 | 45.5 | 12.4 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Thymyl acetate | 1330 | 2.4 | t | 15.2 | ||||||

| δ-Elemene | 1332 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||||

| α-Terpenyl acetate | 1334 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Carvacryl acetate | 1348 | 0.1 | 5.9 | 12.3 | 0.7 | |||||

| Geranyl acetate | 1370 | 4.3 | 0.2 | |||||||

| α-Copaene | 1375 | t | t | 0.1 | ||||||

| β-Bourbonene | 1379 | 0.3 | t | t | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |||

| β-Elemene | 1388 | 0.1 | t | 0.1 | 0.3 | t | ||||

| α-Gurjunene | 1400 | t | t | |||||||

| β-Caryophyllene | 1414 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | t | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| β-Copaene | 1426 | t | t | t | 0.1 | |||||

| trans-α-Bergamotene | 1434 | t | ||||||||

| cis-Muurola-3,5-diene∗ | 1445 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| α-Humulene | 1447 | 0.1 | t | t | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| allo-Aromadendrene | 1456 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | t | 0.3 | 0.6 | t | ||

| γ-Muurolene | 1469 | 0.1 | t | 0.1 | t | 0.1 | ||||

| Germacrene-D | 1474 | t | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |||

| γ-Humulene | 1477 | t | t | |||||||

| Eremophilene∗ | 1480 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Bicyclogermacrene | 1487 | 0.1 | 0.7 | |||||||

| Viridiflorene | 1487 | t | 0.5 | |||||||

| trans-Dihydroagarofuran | 1489 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.5 | ||||

| α-Muurolene | 1494 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | ||||

| β-Bisabolene | 1500 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |||||||

| γ-Cadinene | 1500 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | t | 1.3 | 2.9 | |||

| trans-Calamenene | 1505 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| δ-Cadinene | 1505 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | t | 0.3 | 0.1 | |||

| Kessane∗ | 1517 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.6 | ||||

| α-Calacorene | 1525 | t | t | t | t | |||||

| α-Cadinene | 1529 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | 0.1 | 0.9 | ||||

| Elemol | 1530 | 0.1 | t | t | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||

| trans-α-Bisabolene | 1536 | 0.2 | ||||||||

| Geranyl butyrate | 1544 | 0.1 | t | |||||||

| Spathulenol | 1551 | t | t | t | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||

| β-Caryophyllene oxide | 1561 | 0.1 | t | t | t | t | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||

| Globulol | 1566 | t | t | 0.8 | ||||||

| Geraniol 2-methyl butyrate | 1586 | t | ||||||||

| 10-epi-γ-Eudesmol | 1593 | t | ||||||||

| epi-Cubenol | 1600 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | ||||

| γ-Eudesmol | 1609 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | |||

| τ-Cadinol | 1616 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 2.5 | t | 4.8 | 6.7 | 0.8 | ||

| α-Muurolol | 1618 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | 0.3 | 0.6 | ||||

| β-Eudesmol | 1620 | 0.1 | 0.1 | t | t | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | ||

| Intermedeol | 1626 | t | 3.4 | |||||||

| α-Eudesmol | 1634 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.4 | ||||

| α-Bisabolol | 1656 | t | ||||||||

| Rosadiene∗ | 1993 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Abietatriene | 2027 | t | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| % identification | 99.9 | 96.1 | 99.0 | 99.8 | 98.7 | 99.1 | 97.7 | 94.6 | 98.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Grouped components | ||||||||||

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 22.6 | 13.8 | 17.0 | 24.5 | 24.9 | 29.4 | 39.5 | 23.9 | 7.5 | |

| Oxygen-containing monoterpenes | 74.6 | 68.2 | 76.0 | 69.2 | 64.4 | 68.7 | 41.6 | 47.6 | 82.8 | |

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 2.1 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 4.5 | 7.9 | 2.9 | |

| Oxygen-containing sesquiterpenes | 0.1 | 9.7 | 3.3 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 9.9 | 14.1 | 5.1 | ||

| Diterpenes | 0.1 | |||||||||

| Phenylpropanoids | t | |||||||||

| Others | 0.4 | 0.2 | t | 3.3 | 0.6 | t | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.4 | |

All components were identified based on a lab-made library created with reference essential oils, laboratory-synthesized components, laboratory isolated compounds, and commercial available standards. RI: in-lab obtained retention index relative to C9–C21 n-alkanes on the DB-1 column; t: traces (<0.05%). ∗Tentative identification based only on mass spectra.

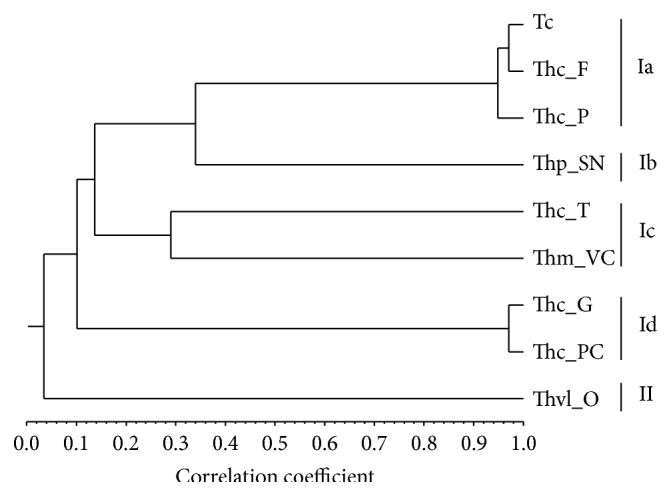

Two poorly correlated clusters (S corr < 0.2) could be identified, Clusters I and II. Cluster I was subdivided into four subclusters (Figure 1 and Table 2). Cluster I grouped eight of the nine samples, all having in common variable percentages of carvacrol (0.1–71%), α-terpineol (0.1–44%), thymol (traces-42%), p-cymene (6–14%), and γ-terpinene (3–11%). Cluster Ia was characterized by dominance of carvacrol (46–71%), whereas in Cluster Ib predominated geraniol (33%), not present in most of the remaining samples. Thymol (14–42%) was the main component in Cluster Ic and α-terpineol (36–44%) in Cluster Id. Thymol and carvacrol were not detected in Cluster II, which was dominated by linalool (66%).

Figure 1.

Dendrogram obtained by cluster analysis of the percentage composition of the essential oils isolated from Thymbra capitata and Thymus species based on correlation and using unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA). For abbreviations, see Table 1.

With variable amounts, these results are in accordance with previous studies on T. capitata as well as Thymus species grown in Portugal (for references, see Section 1).

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

The EOs antioxidant activity was assessed using two methods, based on two distinct mechanisms: electron reaction-based method (TEAC) and hydrogen reaction-based method (ORAC).

Using TEAC method, the EO isolated from Th. caespititius collected in Terceira (Thc_T) showed the highest antioxidant activity (27.3 μmol TE/g EO) in contrast to the lowest antioxidant activity of Th. villosus EO (Thvl_O: 3.7 μmol TE/g EO). Large activity differences were observed among the 5 Th. caespititius EOs assessed (Table 2), with those isolated from plant material collected in mainland Portugal (Praia do Cortiço and Gerês) showing the lowest ability for scavenging ABTS radicals.

The lowest activities observed in Th. villosus and the two Th. caespititius EOs may be related with their main components: linalool and α-terpineol, respectively (Tables 2 and 3), whereas the EOs with highest activity were dominated by thymol (Thc_T) and carvacrol (Tc, Thc_F, and Thc_P). Although geraniol and 1,8-cineole predominated in Th. pulegioides (Thp_SN) and Th. mastichina (Thm_VC) EOs, they showed also relatively high percentages of thymol and carvacrol which may contribute to their scavenging capacity of ABTS (Table 2).

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity of essential oils evaluated by the TEAC and ORAC methods.

| Plant species | Code | TEAC (μmol TE/g essential oil) | ORAC (μmol TE/g essential oil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thymbra capitata | Tc | 25.2 ± 1.3ab | 183.6 ± 9.6a |

| Thymus caespititius | Thc_F | 25.8 ± 1.3ab | 182.8 ± 9.6a |

| Thymus caespititius | Thc_P | 23.0 ± 1.3ab | 170.3 ± 9.6abc |

| Thymus caespititius | Thc_T | 27.3 ± 1.3a | 190.6 ± 9.6a |

| Thymus caespititius | Thc_G | 10.8 ± 1.3c | 144.5 ± 9.6cd |

| Thymus caespititius | Thc_PC | 8.1 ± 1.3c | 127.1 ± 9.6d |

| Thymus mastichina | Thm_VC | 21.2 ± 1.3b | 178.4 ± 9.6ab |

| Thymus pulegioides | Thp_SN | 22.8 ± 1.3ab | 179.4 ± 9.6ab |

| Thymus villosus subsp. lusitanicus | Thvl_O | 3.7 ± 1.3d | 148.4 ± 9.6bcd |

Values in the same column followed by the same letter are not significant by Tukey's multiple range test (p < 0.05).

Dandlen et al. [3] did not observe correlation between Th. caespititius main EO component and the antioxidant activity after assaying the antioxidant activities of six Portuguese thyme EOs, by four methods: thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), free radical scavenging activity through the capacity for scavenging DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl), and the hydroxyl and superoxide anion radicals' scavenging. Indeed, in some cases, the same main component in different EOs of the same species but collected in different places of Portugal had different abilities for scavenging the free radicals and/or preventing lipid peroxidation. In the present work, in the group of Th. caespititius EOs, the highest activities were always in those in which thymol (Terceira) or carvacrol (Faial, Pico) prevailed (Tables 1 and 2).

As it was observed with the TEAC method, all thymol and carvacrol rich EOs (Thc_T, Thc_F, and Tc, Tables 2 and 3) showed also the highest scavenging peroxyl radicals capacity, by the ORAC method. Linalool and α-terpineol rich EOs (Thc_PC, Thc_G, and Thvl_O, Tables 2 and 3) showed the lowest activity.

Thymol and carvacrol's higher capacity for scavenging peroxyl radicals than linalool and 1,8-cineole was previously reported [17, 18]. In contrast to the results obtained in the present work, α-terpineol was considered by Bicas et al. [19] as possessing good capacity for scavenging peroxyl radicals. Since EOs are a complex mixture, this may reflect the presence of some other components that interfere with the capacity of this oxygenated monoterpene for scavenging peroxyl radicals.

3.3. Antiproliferative Activity

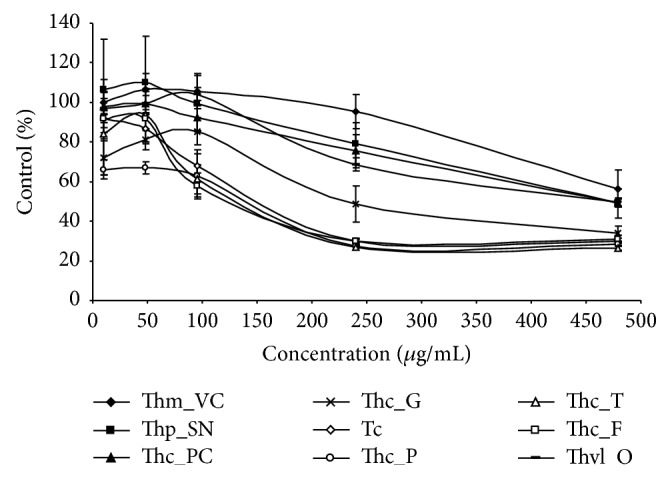

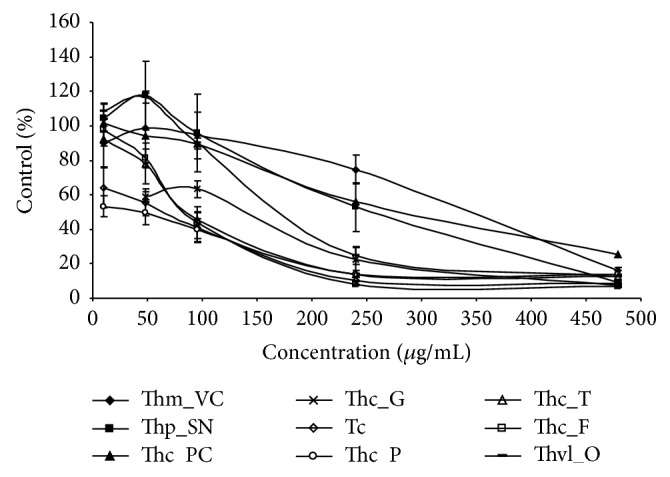

The MTT assay is a sensitive, simple, and reliable method for evaluating antiproliferative activity of plant-based products. The cytotoxic activities of the essential oils of Thymbra and Thymus species from Portugal were studied with the THP-1 leukemia cell line by treating these cells with increasing amounts of the essential oils for 24 and 96 h (Figures 2 and 3). In both cases, essential oils decreased viability of THP-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Antiproliferative activity of the essential oils on THP-1 cell line with 24 h exposure. The mean absorbance values for the negative control (DMSO treated cells) were standardized as 100% absorbance (i.e., no growth inhibition) and results were displayed as absorbance (% of control) versus essential oil concentration.

Figure 3.

Antiproliferative activity of the essential oils on THP-1 cell line with 96 h exposure. The mean absorbance values for the negative control (DMSO treated cells) were standardized as 100% absorbance (i.e., no growth inhibition) and results were displayed as absorbance (% of control) versus essential oil concentration.

After one day (24 h), a great difference was observed between the cytotoxicities of the EOs from Th. mastichina and Th. caespititius from Gerês and even more from that of Pico (Figure 2). These differences were detected even at low concentrations (<50 μg/mL). At 10 μg/mL, only 66% of THP-1 cells survived in the presence of the EO from Th. caespititius from Pico. At higher concentrations (>400 μg/mL), EOs from Th. mastichina, Th. pulegioides, Th. caespititius from Praia do Cortiço, and Th. villosus showed the lowest cytotoxicity (Figure 2). 1,8-Cineole, geraniol, α-terpineol, and linalool were the main components of these EOs. Although thymol was present in low percentages in some samples (Thm_VC and Thp_SN), this was not enough for inhibiting the growth of THP-1 cells. Only EOs with higher thymol and carvacrol percentages were effective in preventing cell proliferation.

After four days (96 h), about 50% of THP-1 cells' survival was observed when exposed to 50 μg/mL of Th. caespititius from Pico and T. capitata carvacrol rich EOs (Figure 3). At 100 μg/mL, the survival was about 40%. The same survival percentage was observed for Th. caespititius from Terceira and Faial EOs with thymol and carvacrol as main components, respectively. At that concentration, the survival of cells was even about 90% in the presence of Th. mastichina, Th. pulegioides, and Th. villosus EOs. At 250 μg/mL of EOs from Th. caespititius from Pico, Terceira, and Faial and T. capitata, only about 10% of THP-1 cells survived. With EOs from Th. caespititius from Praia do Cortiço, Th. pulegioides, and Th. mastichina, the survival percentages were still >50%, mainly that of Th. mastichina EO (>70%).

These results support the importance of carvacrol and thymol among EOs components, since when present at low percentages the EOs did not inhibit the growth of THP-1 cells. The antiproliferative activity of thymol and carvacrol as well as Th. vulgaris EO against THP-1 cells was also reported by Aazza et al. [17]. Origanum onites carvacrol rich EO, between 62.5 and 125 μg/mL, also presented toxicity against 5RP7 cancer cells (c-H-ras transformed rat embryonic fibroblasts) [20]. Also, Satureja sahendica thymol rich EO significantly reduced cell viability of the human colon adenocarcinoma (SW480), human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF7), choriocarcinoma (JET 3), and monkey kidney (Vero) cell lines [21].

4. Conclusions

In the Portuguese Thymbra and Thymus EOs studied, two main clusters were identified: one cluster grouping 8 samples with diverse percentages of carvacrol, α-terpineol, thymol, p-cymene, and γ-terpinene and the other cluster with only one EO in which linalool predominated and thymol and carvacrol were absent.

EOs with higher percentages of thymol and carvacrol showed the highest capacity for scavenging free radicals and preventing the growth of THP-1 cells.

Acknowledgment

This study was partially funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), under Pest-OE/EQB/LA0023/2011 and UID/AMB/50017/2013.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests concerning this paper.

References

- 1.Figueiredo A. C., Barroso J. G., Pedro L. G., Salgueiro L., Miguel M. G., Faleiro M. L. Portuguese Thymbra and Thymus species volatiles: chemical composition and biological activities. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008;14(29):3120–3140. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbosa P., Faria J. M. S., Mendes M. D., et al. Bioassays against pinewood nematode: assessment of a suitable dilution agent and screening for bioactive essential oils. Molecules. 2012;17(10):12312–12329. doi: 10.3390/molecules171012312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dandlen S. A., Lima A. S., Mendes M. D., et al. Antioxidant activity of six Portuguese thyme species essential oils. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 2010;25(3):150–155. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado M., Sousa M. D. C., Salgueiro L., Cavaleiro C. Effects of essential oils on the growth of Giardia lamblia trophozoites. Natural Product Communications. 2010;5(1):137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machado M., Dinis A. M., Salgueiro L., Cavaleiro C., Custódio J. B. A., do Céu Sousa M. Anti-Giardia activity of phenolic-rich essential oils: effects of Thymbra capitata, Origanum virens, Thymus zygis subsp. sylvestris, and Lippia graveolens on trophozoites growth, viability, adherence, and ultrastructure. Parasitology Research. 2010;106(5):1205–1215. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miguel M. G., Almeida M. L., Gonçalves M. A., Figueiredo A. C., Barroso J. G., Pedro L. M. Toxic effects of three essential oils on Ceratitis capitata . Journal of Essential Oil-Bearing Plants. 2010;13(2):191–199. doi: 10.1080/0972060x.2010.10643811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miguel M. G., Antunes M. D., Rohaim A., Figueiredo A. C., Pedro L. G., Barroso J. G. Stability of fried olive and sunflower oils enriched with Thymbra capitata essential oil. Czech Journal of Food Sciences. 2014;32(1):102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmeira-de-Oliveira A., Gaspar C., Palmeira-de-Oliveira R., et al. The anti-Candida activity of Thymbra capitata essential oil: effect upon pré-formed biofilm. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;140(2):379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmeira-de-Oliveira A., Palmeira-de-Oliveira R., Gaspar C., et al. Association of Thymbra capitata essential oil and chitosan (TCCH hydrogel): a putative therapeutic tool for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidosis. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 2013;28(6):354–359. doi: 10.1002/ffj.3144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto E., Gonçalves M. J., Hrimpeng K., et al. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of Thymus villosus subsp. lusitanicus against Candida, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus and dermatophyte species. Industrial Crops and Products. 2013;51:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Council of Europe (COE) European Pharmacopoeia. 6th. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe (COE); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faria J. M. S., Barbosa P., Bennett R. N., Mota M., Figueiredo A. C. Bioactivity against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: nematotoxics from essential oils, essential oils fractions and decoction waters. Phytochemistry. 2013;94:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antunes M. D. C., Dandlen S., Cavaco A. M., Miguel G. Effects of postharvest application of 1-MCP and postcutting dip treatment on the quality and nutritional properties of fresh-cut kiwifruit. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(10):6173–6181. doi: 10.1021/jf904540m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ou B., Hampsch-Woodill M., Prior R. L. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49(10):4619–4626. doi: 10.1021/jf010586o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao G., Prior R. L. Measurement of oxygen radical absorbance capacity in biological samples. Methods in Enzymology. 1998;299:50–62. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1983;65(1-2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aazza S., Lyoussi B., Megías C., et al. Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative activities of Moroccan commercial essential oils. Natural Product Communications. 2014;9(4):587–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bentayeb K., Vera P., Rubio C., Nerín C. The additive properties of Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) assay: the case of essential oils. Food Chemistry. 2014;148:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bicas J. L., Neri-Numa I. A., Ruiz A. L. T. G., de Carvalho J. E., Pastore G. M. Evaluation of the antioxidant and antiproliferative potential of bioflavors. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49(7):1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bostancioĝlu R. B., Kürkçüoĝlu M., Başer K. H. C., Koparal A. T. Assessment of anti-angiogenic and anti-tumoral potentials of Origanum onites L. essential oil. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2012;50(6):2002–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousefzadi M., Riahi-Madvar A., Hadian J., Rezaee F., Rafiee R. In vitro cytotoxic and antimicrobial activity of essential oil from Satureja sahendica . Toxicological and Environmental Chemistry. 2012;94(9):1735–1745. doi: 10.1080/02772248.2012.728606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]