Abstract

Mucormycosis is an uncommon acute invasive fungal infection that affects immunocompromised patients. It progresses rapidly and has poor prognosis if diagnosed late. Early detection, control of the underlying condition with aggressive surgical debridement, administration of systemic and local antifungal therapies, hyperbaric oxygen as adjunctive treatment improves prognosis and survivability.

Mucormycosis also known as zygomycosis and phycomycosis is an uncommon, opportunistic, aggressive fatal fungal infection caused by fungi of the order Mucorales, frequently among immunocompromised patients. This fungal infection begins from the sinonasal mucosa after inhalation of fungal spores; the aggressive and rapid progression of the disease may lead to orbital and brain involvement.1-4 In the past, the mortality rate of the rhino-cerebral type was 88%, but recently the survival rate of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis averages 21-73% depending on the circumstances.1 Mucormycosis is classified according to anatomical site into rhino-cerebral, which is the most common, central nervous system, pulmonary, cutaneous, disseminated, and miscellaneous.1,2,4-6 The rhino-orbito-cerebral is the most common form of mucormycosis.3 The most common predisposing factor is uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM), especially when the patient has a history of ketoacidosis, these species thrive best in a glucose rich and acidic environment.3,4,6,7 Immunosuppressive drugs such as steroids, neutropenia, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, dialysis patients on deferoxamine, malnutrition, hematologic malignancy, and organ transplant patients are also at risk of affection by the fungi.1,4-7 This case report describes a case of rhino-orbital mucormycosis affecting a diabetic female with good prognosis and satisfactory healing. Our objective in presenting this particular case is to emphasize that early diagnosis and proper management leads to good prognosis and high survivability.

Case Report

A 62-year-old female presented to the outpatient clinic complaining of pain and swelling of her right cheek. Clinical examination revealed redness and swelling of her right cheek with the presence of fistulous tracts, right facial nerve palsy, and periorbital swelling. Intra-oral examination revealed necrotic bare bone of the right side of the hard palate (Figure 1). She gave a history of uncontrolled insulin dependent DM, controlled hypertension, liver cirrhosis as a result of hepatitis C virus, and a history of previous functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) for treatment of cheek swelling and chronic sinusitis. Laboratory investigations revealed: white blood cell (WBC’s) 6.66×103, impaired kidney function, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 32 mg/dl, creatinine 1 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase (AST) 73 U/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) 73 U/L, albumin 3.3 g/dl, hemoglobin 10 mg/dl, platelet count 95×103, and random blood glucose 160 mg/dl (normal range: <125 mg/dl). The CT scans revealed sequestrated right maxilla up to the infraorbital rim and opacification of the maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid air sinuses (Figure 2). Clinical and radiographic data were indicative of invasive fungal infection. She was planned for aggressive surgical debridement with right hemimaxillectomy. She was admitted to the operating room for execution of the preoperative plan under general anesthesia. During the surgery, an old piece of gauze was discovered in the maxillary sinus that was missed from the previous FESS, black eschar nasal discharge, and blackish necrosis of the nasal mucosa were observed (Figure 3) and further debridement was carried by inferior turbinectomy. Irrigation was carried out, and the specimen was sent for histopathological confirmation and culture and sensitivity test. She was discharged to the ward extubated and fully conscious. Postoperative medications included a combination of intermediate and short acting insulin therapy for tight glycemic control, intravenous administration of Amphotericin B (AmB) 1 mg/kg/day with daily monitoring of the kidney functions, IV ampicillin/sulbactam 1g/0.5 g twice daily, IV Diclofenac sodium 150 mg/day, and IV Ranitidine 100 mg/day. Postoperative care included local irrigation with normal saline and local packing of a piece of gauze soaked in 1 vial of AmB 50 mg twice daily. Histopathology confirmed mucormycosis, microscopic slides stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin showed clusters of spores and hyphae with right angle branching and evidence of sinonasal mucosa and bone necrosis (Figure 4). Twenty dives of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) under pressure of 2 atmosphere (ATA) with 100% oxygen saturation were given immediate postoperatively, and she showed signs of clinical improvement. The postoperative laboratory investigations revealed evidence of impaired kidney functions where BUN and serum creatinine increased gradually after 4 days; BUN was 81 mg/dl and serum creatinine was 2.0 mg/dl, yet the decision was to continue the medications, and the follow up labs were stable. The AmB was administered for a total of 20 days. Improvement was noticed during treatment as symptoms relieved, swelling subsided, discharge stopped, and surgical defect margins showed proper healing with healthy vascularized tissue. Radiographs showed proper clearance of the opacification of both ethmoid and sphenoid air sinuses (Figure 5). She was discharged after 36 days. One year follow up shows clinical improvement; the tissue margins appear healthy and vascularized (Figure 6).

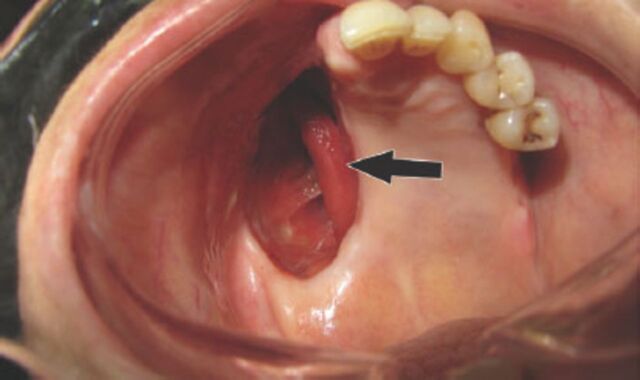

Figure 1.

An image showing the palatal necrotic bone in a diabetic female patient with rhino-orbital mucormycosis.

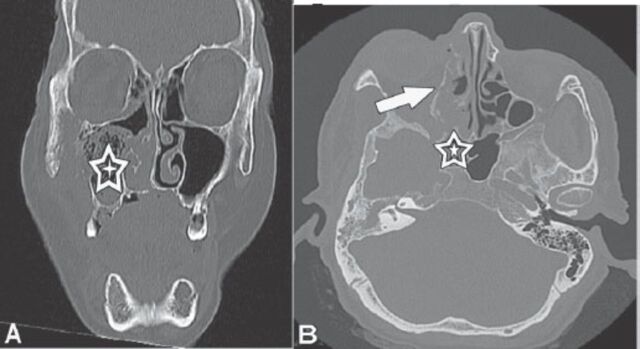

Figure 2.

A coronal CT scan showing: A) sequestration of the right maxilla and clouding of maxillary air sinus (star), and B) axial CT showing opacification of the right ethmoid (arrow) and right sphenoid air sinuses (star).

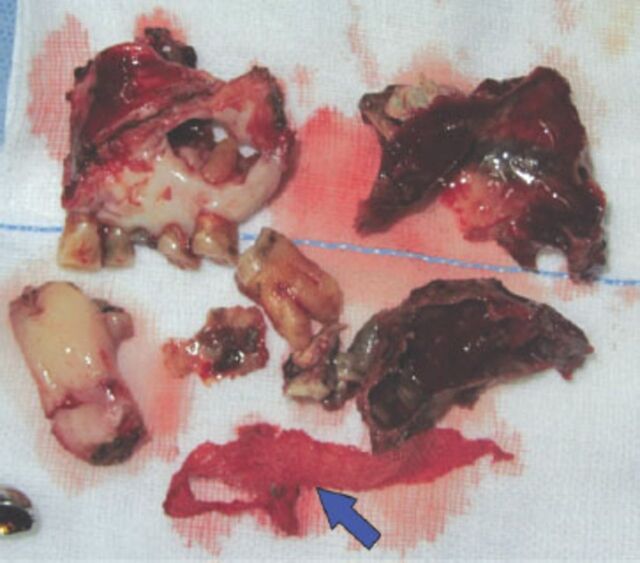

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photograph of the right maxilla and inferior turbinate after excision. A piece of gauze that was previously missed is shown on the lower edge of the picture (blue arrow).

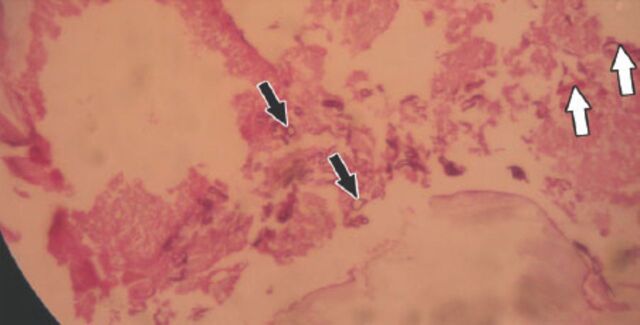

Figure 4.

Histopathological specimen stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin at 400× magnification, showing colonies of fungal spores (black arrows) and hyphae (white arrows).

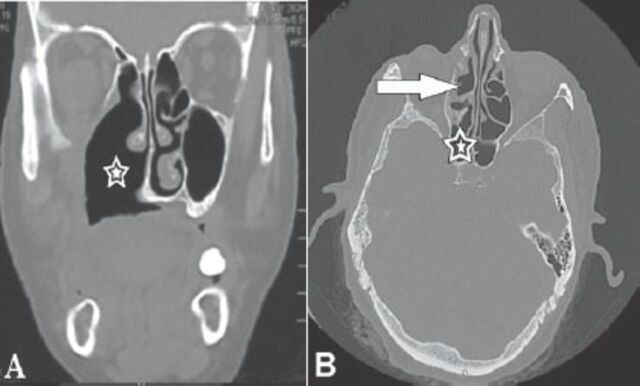

Figure 5.

An image showing: A) removal of inferior turbinate as it appears in the coronal cut (star), and B) axial CT showing clear ethmoid (arrow) and sphenoid sinuses (star).

Figure 6.

An image showing after hyperbaric oxygen therapy treatment, the tissue margins appear healthy and vascularized.

Discussion

Mucormycosis is an uncommon fulminating fungal infection which is aggressive and has a fatal outcome if untreated. This infection is caused by many genera of saprophytic fungi related to phycomycetes (zygomycetes) and order Mucorales. The most common species are Rhizopus, Absidia and Mucor.7 Mucormycosis is abundant in soil and moldy organic materials.1,2,4,5 It affects immunocompromised patients specially uncontrolled diabetics, which is the most common predisposing factor especially when it is combined with ketoacidosis, where ketone bodies displace the iron bound to serum proteins thus increasing free iron in serum, which permits growth of fungi, also due to decreased neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis in the patients with diabetic ketoacidosis.3,4,7,8 It was reported that 88.2% of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis had uncontrolled DM, and 53.3% of them had diabetic ketoacidosis.3 Recently, the mortality rate between diabetic patients ranges from 20-40%. The mortality rate among patients depends on the timing of diagnosis.7 Hyperglycemia, low oxygen tension and ketoacidosis diabetic patient provide a good medium for growth of the fungus.8 The mortality rate of patients with orbital involvement is up to 33%.1 Mucormycosis begins at the inferior and middle meatuses, then spread to the paranasal sinuses, and may spread to the orbital and brain tissues.1 The airborne spores of the fungi may spread through inhalation, or through a wound, or an extraction socket to reach the nasal cavity or oral cavity, then invades blood vessels to spread to the orbit and brain, and once the brain is involved the prognosis is poor.1,3-5,8 The mortality rates were 24% in rhino-orbital cases, and 62% in rhino-cerebral cases. The fungus has great affinity to arteries and adheres to its walls, then grows along their internal elastic lamina leading to thrombosis, then ischemia and necrosis of the surrounding tissues. There is no definitive diagnosis for mucormycosis, except by histopathologic confirmation by visualization of board, non-septate hyphae with right angle branching of the involved tissue.1,3,5,7,8

The first clinical signs in rhino-cerebral mucormycosis presented with headache, facial swelling, pain, periorbital edema, black eschar nasal discharge, and if the fungal infection extended to nasal turbinate, the orbital structures become involved may lead to proptosis, chemosis, resulting in ophthalmoplegia, and loss of vision.4,6,8,9 Regarding our case, the piece of gauze that was missed during her previous FESS provided an excellent medium for the fungus to fester and fulminate, thus once discovered intraoperatively, and the blackish necrosis of the nasal mucosa was noticed so a more aggressive debridement was performed, and the postoperative medications were adjusted as such. Through the superior orbital fissure the disease may extend to the cavernous sinus and cause brain infarctions. Once the disease extends to the brain, the patient suffers from decreased consciousness and then coma, where the prognosis becomes poor.6 The clinical progression of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis is classified into 3 stages: stage 1 - infection of nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses, as in our case; stage 2 - orbital involvement leading to superior orbital fissure syndrome and orbital apex syndrome; and stage 3 - cerebral involvement leading to cavernous sinus thrombosis, occipital and frontal lobe infarctions (it has poor prognosis and has high mortality rate).8

Radiological investigations are essential for proper diagnosis. The main radiological investigation is CT due to its availability, shows bone destruction, clouding and thickening of the nasal and paranasal mucosa, and its low cost. The MRI is preferred in detecting soft tissue, vascular, and intracranial extensions. In our case, CT scans revealed clouding and mucosal thickening of paranasal sinuses and maxillary bone destruction.4,6,8 The management protocol involved control of the predisposing factors, aggressive surgical debridement, systematic administration and local irrigation with antifungal therapy, hyperbaric oxygen and iron chelation as adjunctive treatments.1,3-5,8 The control of predisposing factor, such as control of diabetes, control of underlying hematologic malignancies and immunosuppressive drugs, which what primarily induced the infection.3,4,8 In our case, the systemic condition of the patient was adjusted prior to surgical procedure. The surgical procedure is very important through debridement of infected and necrotic tissue to stop progression of the disease, and to allow antifungal drugs to reach the ischemic areas, the delay of surgical procedure leads to poor prognosis.3,4,7

A piece of gauze soaked with AmB was placed inside the defect to allow more tissue penetration of the drug.7 AmB was reported to be the most successful antifungal agent in the management of mucormycosis but has many complications, such as impairment of kidney functions and electrolyte imbalance.7,9 These side effects can be avoided by its lipid preparation; liposomal AmB remains longer in circulation, thus able to reach most of tissues and inflammation areas.4 Recently in some case reports,8 hematologic malignancy patients revealed liposomal AmB has more advantages and the survival rate is increased from 39-67% with patients treated with liposomal AmB. The dose of AmB ranges from 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day depending on the severity of infection, renal function, and nature of pathogenesis.6 The duration of the antifungal therapy is individualized to every case. Posaconazole has some success in in-vitro studies and approved, but it is not recommended as a first antifungal in mucormycosis. Posaconazole in combination with AmB has reported no additional benefit over AmB.4

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is a beneficial adjunctive treatment, especially in diabetic patients with mucormycosis with a survival rate of up to 94%.10 High concentration of oxygen is fungicidal and has many advantages, such as improve neutrophil activity, inhibit growth of mucorales, improve flow of oxygen to ischemic tissues, and improve wound healing by releasing growth factors.4,8,10 Many reports in the literature recommend the combination between standard therapy and HBO as an adjunctive treatment in rhino-cerebral mucormycosis to improve the patient’s prognosis. A previous study8 revealed a 22% survival rate of patients who received standard therapy compared to 83% survival rate of patient who received standard therapy and HBO. The standard pressure in the hyperbaric chamber is 2.5 to 3 ATA, and 100% oxygen saturation.4 Also the iron chelator as deferasirox is considered as adjunctive treatment, the free iron is essential for pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Iron chelators inhibit the growth of the fungus through prevention of absorption of iron.4,8

In conclusion, rhino-cerebral mucormycosis is a fulminating type of invasive fungal acute infection that can be encountered mostly in immunocompromised patients. We conclude that early detection of mucormycosis is essential for good prognosis. After rapid aggressive surgical debridement, systemic and local AmB with HBO may improve the outcome of the disease.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Viterbo S, Fasolis M, Garzino-Demo P, Griffa A, Boffano P, Iaquinta C, et al. Management and outcomes of three cases of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp GR, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Infection. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 253–254. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto ME, Manrique HA, Guevara X, Acosta M, Villena JE, Solis J. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state and rhino-orbital mucormycosis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:e37–39. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mankekar G. Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis. Springer (India): Private Limited; 2014. pp. 1–4. 9, 16,17, 28-31, 51, 52, 63,65, 66, 68, 69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzen D, Böhm H, Zimmermann M, Reuther T, Kubler AC, Müller-Richter DA. Mucormycosis of the head and neck. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:e321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Fortson JK, Cook HE. A fatal outcome from rhino-cerebral mucormycosis after dental extractions: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:693–697. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wali U, Balkhair A, Al-Mujaini A. Cerebro-rhino orbital mucormycosis: an update. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dökmetaş HS, Canbay E, Yilmaz S, Elaldi N, Topalkara A, Öztoprak I, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis and rhino-orbital mucormycosis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2002;57:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(02)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kok J, Gilroy L, Halliday C, Lee OC, Novakovic D, Kevin P, et al. Early use of posaconazole in the successful treatment of rhino-orbital mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus oryzae. J Infect. 2007;55:e33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.05.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John BV, Chamilos G, Kontoyiannis DP. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjunctive treatment for zygomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:515–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]