CDI has a substantial epidemiologic, and economic, burden; and the largest proportion of costs arise from prolonged hospitalization. Interventions reducing the severity of infection and/or relapses requiring rehospitalization are likely to have the largest absolute effect on direct medical cost.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, economic burden, epidemiology, hospital-acquired infections, model

Abstract

Background. Limited data are available on direct medical costs and lost productivity due to Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in Canada.

Methods. We developed an economic model to estimate the costs of managing hospitalized and community-dwelling patients with CDI in Canada. The number of episodes was projected based on publicly available national rates of hospital-associated CDI and the estimate that 64% of all CDI is hospital-associated. Clostridium difficile infection recurrences were classified as relapses or reinfections. Resource utilization data came from published literature, clinician interviews, and Canadian CDI surveillance programs, and this included the following: hospital length of stay, contact with healthcare providers, pharmacotherapy, laboratory testing, and in-hospital procedures. Lost productivity was considered for those under 65 years of age, and the economic impact was quantified using publicly available labor statistics. Unit costs were obtained from published sources and presented in 2012 Canadian dollars.

Results. There were an estimated 37 900 CDI episodes in Canada in 2012; 7980 (21%) of these were relapses, out of a total of 10 900 (27%) episodes of recurrence. The total cost to society of CDI was estimated at $281 million; 92% ($260 million) was in-hospital costs, 4% ($12 million) was direct medical costs in the community, and 4% ($10 million) was due to lost productivity. Management of CDI relapses alone accounted for $65.1 million (23%).

Conclusions. The largest proportion of costs due to CDI in Canada arise from extra days of hospitalization. Interventions reducing the severity of infection and/or relapses leading to rehospitalizations are likely to have the largest absolute effect on direct medical costs.

Evidence is accumulating that the epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection is worsening, with marked increases in both incidence and case-fatality in Canada [1], the United States [2, 3], Europe [4], and other countries [5]. Although the reasons are multifactorial, 1 cause is the emergence of a new, “hypervirulent” strain designated restriction endonuclease analysis type BI, North American pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type 1 (NAP1), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ribotype 027 (ie, BI/NAP1/027) [6]. Although it was first identified in Quebec [7], transmission of this strain is now of global concern [8]. In addition, although it is not known whether recurrence rates have changed, reduced susceptibility and increased rates of C difficile infection are being observed in the community [9].

The existing literature on the burden of illness of C difficile infection is sparse, with incidence estimates derived primarily from teaching hospitals [1]. As such, there are no published Canada-wide estimates of the prevalence or the economic burden attributable to C difficile infection. The objective of this study was to estimate the annual number of persons infected with C difficile in Canada in 2012 and the direct medical and lost productivity costs.

METHODS

Using prevalence-based burden of illness model, we estimated the annual mean number of persons infected with C difficile in Canada and the direct medical costs and lost productivity costs [10]. Numbers of infected persons were tabulated by treatment location (acute care hospital, community-dwelling, and long-term care) and, for those in acute care, stratified by first versus recurrent infection, disease severity, and age group [11].

Given its episodic nature, the mean number of infections per province between 2010 and 2012 was estimated. These data are from a laboratory that uses PCR methods for diagnosis of C difficile. Resource use and costs of typical management patterns were estimated for each treatment location and other stratification variables. A societal perspective was adopted by including lost productivity costs. The model was developed in Microsoft Excel 2010, and the statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 12.

Data Sources

Sources of data used included the following: (1) the number of bed-days attributed to persons infected with C difficile in Canadian acute care hospitals, from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); (2) the estimated proportion of recurrent acute care infections, from the Providence Health Care ([PHC] Vancouver, British Columbia) Infection Prevention and Control C difficile infection surveillance program dataset; and (3) the estimated proportions of infections occurring among hospital- and community-based individuals and distributions of severity, obtained from the literature [12, 13].

Resources expended for diagnosing persons in Canada infected with C difficile came from published literature, clinician interviews, and data from PHC Infection Prevention and Control and other Canadian surveillance programs (Table 1). Costs were obtained from PHC Infection Prevention and Control and PHC Finance. Clinical experts included hospital (n = 3) and community (n = 1) physicians and infection control experts (n = 2), medical directors of long-term care facilities (n = 3), and acute care nurses who care for patients infected with C difficile (n = 2). Lost productivity was quantified using labor statistics [14]. Use of the PHC Infection Prevention and Control data was approved by the ethical review boards of PHC and the University of British Columbia.

Table 1.

Estimated Mean Number of Initial and Recurrent Infections of Clostridium difficile Occurring in Canadian Hospitals, 2012

| Province | Rate of New C difficile Infections per 10 000 Bed-Daysa | Total Number of Bed-Daysb | Number of Infections in Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2.8 | 422 501 | 118 |

| Prince Edward Island | 2.8 | 126 014 | 35 |

| Nova Scotia | 2.8 | 806 400 | 226 |

| New Brunswick | 2.8 | 735 996 | 206 |

| Quebec | 17.0 | 5 560 668 | 9453 |

| Ontario | 6.0 | 6 924 115 | 4154 |

| Manitoba | |||

| Saskatchewan | 3.4 | 829 701 | 282 |

| Alberta | 6.6 | 2 430 875 | 1636 |

| British Columbia | 8.3 | 2 834 776 | 2353 |

| Yukon | 6.3 | 15 138 | 10 |

| Northwest Territories | 6.3 | 24 208 | 15 |

| Nunavut | 6.3 | 4946 | 3 |

| Canada | 18.492 |

a Mean rate from Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program for fiscal years 2011 and 2012 for all jurisdictions except British Columbia (Provincial Infection Control Network), Manitoba (back calculated from Manitoba Health), and the Territories (national average).

b From the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

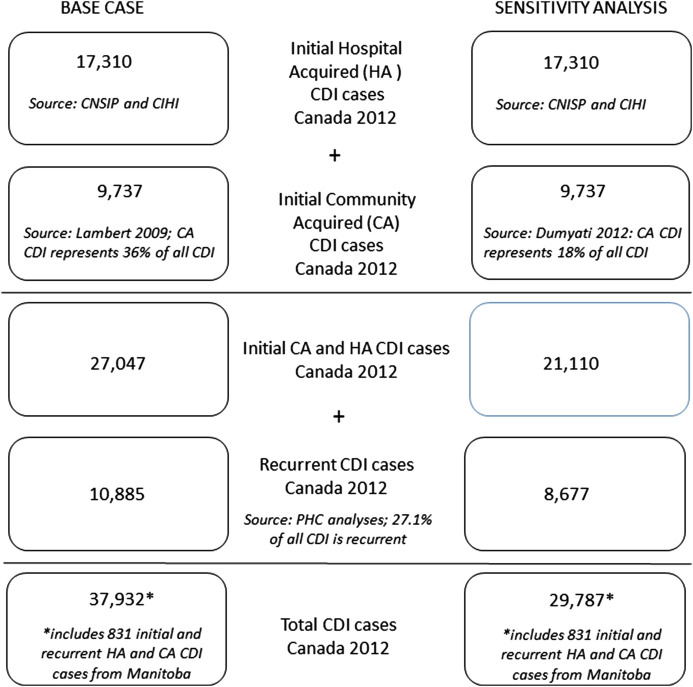

Number of Infected Persons With Clostridium difficile in Canada

The annual aggregated number of initial and recurrent infections in Manitoba was obtained from published sources [12, 15]. Other than Manitoba, there is no published information on the numbers of C difficile in Canadian provinces or territories so these estimates were derived indirectly (Figure 1 ). In step 1, the province-specific mean annual estimated rates of persons newly infected in hospital were multiplied by the total number of patient days per province from CIHI [12, 16–20]. In step 2, the numbers of person newly infected while living in the community or in long-term care were estimated by using the ratio of hospital- to community-based source of infections observed in Manitoba: 64.2 to 35.8 [12]. In step 3, the province-specific numbers of infections were determined by adding in the estimated proportion of C difficile infections that were recurrent (0.271). Because of different definitions of time periods reported by different agencies, recurrent infections included both relapses (variously defined as within 4, 6, or 8 weeks of initial infection) and reinfections.

Figure 1.

Estimated number of infections and of Clostridium difficile in Canada in 2012, base infection assumptions and sensitivity analysis.

Stratification

The costs of treating C difficile depend on the severity of illness, location of treatment, and patient age. Severity was classified according to the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America-Infectious Diseases Society of America (SHEA-IDSA) guidelines definitions of mild-to-moderate, severe, and fulminant infection [11]. Estimates of the distribution of infections by severity were taken from the literature [21] and from the PHC Infection Prevention and Control program, which showed that 2.1% of hospital infections result in fulminant disease.

As a result of a lack of population-based Canadian data, the proportion of infections managed in hospital (53%) was based on data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project [22]. In the base case, the number of infections (n = 1605) managed in long-term care was imputed based on a recent US population-based study [22].

Management and Resource Use

The frequency of tests among community-managed C difficile infections was estimated from the literature [23, 24], and the severity-specific mean number of physician visits was elicited from clinical experts. Pharmacologic treatment was assumed to follow the SHEA-IDSA guidelines for hospitalized patients [11]. The costs of managing severe or recurrent C difficile infections in the community were based on 2011 data [25, Personal Communication with community pharmacist in Ontario, February 13, 2012].

Costs

Direct costs attributable included the following: laboratory tests, hospitalizations for other causes that were extended due to infection, rehospitalization due to infection, medication, surgical procedures, and physician visits (Appendix Table 1) [26, 27]. Incremental costs of in-hospital resource use were estimated from the PHC Infection Prevention and Control dataset using a generalized linear regression model.

Estimates for lost productivity while in hospital were derived by multiplying the number of days in hospital attributable to C difficile infection by age-specific probabilities of being employed, of working full time, and by the 2012 mean daily wage rate [14].

Unit costs were inflated to 2012 Canadian dollars ($CAD) where necessary using the healthcare component of the Canadian consumer price index. Costs of infection control practices and of direct nonmedical resources were excluded.

Sensitivity Analyses

Key parameters were varied in sensitivity analyses. The proportion of infections managed in hospital was varied in sensitivity analyses, assuming the frequency of hospital treatment for C difficile infections was as high as 70% of all infections (based on clinical experts). In another sensitivity analysis, it was assumed that 7108 infections would be managed in long-term care based on recent population-based data from Canada and the United States (suggesting that 25% of cases originate from the long-term care, and that 10% of these require hospitalization) [12, 22].

In the absence of robust data, a plausible range of number of infections was determined as ±10% of the base case. This number was derived as follows: Manitoba Health reported 831 hospital or community, initial or recurrent, C difficile infections over 2010–2012. Using the algorithm used here based on Canadian Nocosomial Infection Surveillance Program data, we calculated that 752 infections occurred in Manitoba over the same period, indicating that the algorithm underestimated the actual number of infections by 9%. To estimate a plausible range of direct costs, the PHC Infection Prevention and Control dataset was bootstrapped 1000 times; the generalized linear model was fit at each iteration, and the estimated cost was recorded. Costs were log transformed, and a log likelihood with Gamma link model was fit to the data. A confidence interval was then calculated from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrapped estimates [28]. A detailed description of the cost analyses is available upon request.

RESULTS

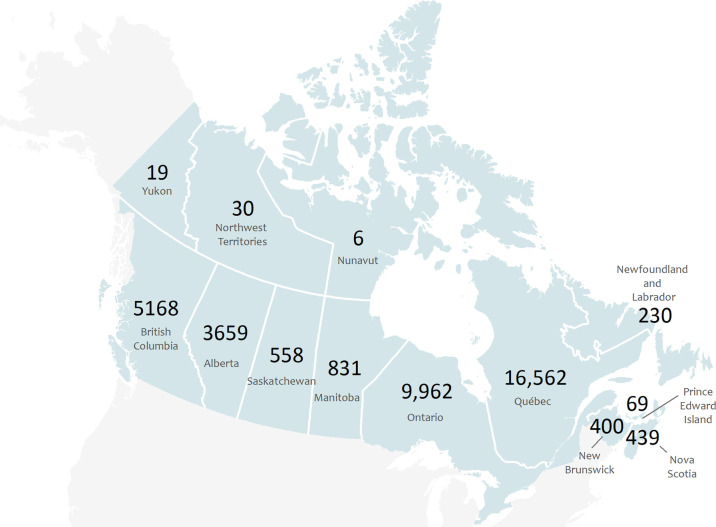

There were an estimated 37 932 (plausible range, 34 139–41 725) C difficile infections in Canada in 2012, including 20 002 (plausible range, 18 018–22 022) in hospital, 16 326 (plausible range, 14 693–17 959) in the community, and 1604 (plausible range, 1444–1764) in long-term care institutions (Figure 1). The total number of bed-days attributable to (Table 2) infections with C difficile was highest in Quebec, followed by Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta. Of those in hospital, approximately 73% were new infections and 27% were recurrent, 61% were mild to moderate, and 54% occurred in those aged 75 years and older. Quebec had the highest total number of infections, followed by Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of the Incidence of Clostridium difficile Infection in Canada in 2012 According to Treatment Location, Type of Infection, Disease Severity, and Age Group

| Patient Location | Characteristic of the Infection | Proportion | Number of Infections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | |||

| Type of Infection | |||

| New infection | 0.73 | 14 593 | |

| First relapse | 0.16 | 3134 | |

| Subsequent relapse | 0.05 | 1020 | |

| Reinfection | 0.06 | 1254 | |

| Disease Severity | |||

| Mild to moderate | 0.61 | 12 155 | |

| Severe | 0.37 | 7435 | |

| Fulminant infection | 0.02 | 412 | |

| Age Group (years) | |||

| <65 | 0.30 | 5944 | |

| 65–74 | 0.16 | 3161 | |

| ≥75 | 0.54 | 10 897 | |

| Community | |||

| Incidence | 16 326 | ||

| Disease Severity | |||

| Mild to moderate | 0.80 | 13 061 | |

| Severe | 0.20 | 3265 | |

| Fulminant infection | 0 | 0 | |

| Long-term care | |||

| Incidence | 1604 | ||

Figure 2.

Estimated number of infections and of Clostridium difficile in Canadian provinces and Territories in 2012.

Resource use and unit cost estimates are provided in Appendix Table 2. The largest component was the incremental hospitalization costs of C difficile infection, with an estimated mean of $11 930 for the initial episode and $15 330 for a recurrent episode. The largest portion of this difference was due to the longer mean number of hospital days attributable to C difficile for recurrent infections.

The economic burden was estimated to surpass CAD $280 million dollars (plausible range, $254 to $309 million dollars), almost 90% of which was incurred in hospital (Table 3). Treating 5400 recurrent infections in the hospital was estimated to account for over $80 million. Four percent ($12 million) of the burden was incurred as direct medical costs in the community, and 4% ($10 million) was due to lost productivity.

Table 3.

Estimated Costs of Treating Initial and Recurrent Infection of Clostridium difficile in Canada, 2012, According to Patient Location and Category of Cost

| Patient Location | Category of Cost | Total Estimated Cost (2012 $CAD, Thousands) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct medical costs | ||

| Hospital | Pharmacotherapy | 237 |

| Physician costs | 6649 | |

| Other hospitalization visits | 252 709 | |

| Total in-hospital | 259 595 | |

| Community and long-term care | Tests and procedures | 602 |

| Pharmacotherapy | 6356 | |

| Physician and nursing visits | 5198 | |

| Total community cost | 12 157 | |

| Lost productivity | 9613 | |

| Total costs | 281 365 | |

Abbreviations: $CAD, Canadian dollars.

The key inputs to which the model results were the most sensitive included the following (Table 4): (1) the length of stay in hospital attributable to C difficile, which resulted in a decrease in total costs of 40% when the mean number of days was reduced from 13.6 to 6.0; and (2) the ratio of hospital-based to community-based management, which resulted in an increase in total costs of 65% when the ratio changed from 53:47 to 70:30.

Table 4.

The Impact of Varying Key Assumptions in Sensitivity Analyses on the Total Cost of Treating Clostridium difficile Infections in Canada, 2012

| Model Input | Base Case Value (Source) | Sensitivity Analysis (Source) | Total Cost (2012 $CAD, Thousands) | % Change vs Baseline Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low estimate of CDI-associated hospitalization cost ($CAD) | 11 930 (IPACa) | 3550 (IPACb) | 148 598 | −47 |

| LOS in hospital (days) | 13.6 (IPAC) | 6 [27] | 160 119 | −43 |

| Ratio of HB to CB infection | 64:36 ([12]) | 82:18 ([29]) | 222 257 | −21 |

| Cost per recurrent infection ($CAD) | 15 330 (IPACc) | 11 930 (IPACa) | 267 233 | −5 |

| % of infections that were recurrent | 20.8 (IPACd) | 13.7 (IPACe) | 279 171 | −1 |

| Incidence in LTC | 1604 ([22]) | 7108 ([12], [30]) | 280 773 | −0 |

| Baseline estimate | 281 365 | 0 | ||

| Ratio of HB to CB management | 53:47 ([22]) | 70:30 (EO) | 366 869 | 30 |

| High estimate of CDI-associated hospitalization cost ($CAD) | 11 930 (IPACa) | 19 930 (IPACf) | 408 224 | 45 |

Abbreviations: $CAD, Canadian dollar; CB, community-based; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; EO, expert opinion; HB, hospital based; IPAC, Providence Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control dataset; LOS, length of stay; LTC, long-term care.

a Adjusted cost per infection.

b 2.5th percentile of bootstrapped adjusted cost per infection.

c Adjusted cost per recurrent infection.

d Infections ≤8 weeks of initial infection.

e Infections ≤4 weeks of initial infection.

f 97.5th percentile of bootstrapped adjusted cost per infection.

DISCUSSION

Management of hospital-acquired infections in Canada has been broadly characterized as “crisis-motivated” or “reactive”, with an influx of resources when an outbreak becomes severe, such as the hypervirulent strain of C difficile in Quebec [31]. As such, most Canadian infection control programs do not meet expert recommendations with regards to investments in infection controls programs [32].

Applying reasonable assumptions to the limited existing Canadian data, there were an estimated 38 000 infections of C difficile infection in 2012 that, under conservative assumptions, cost CAD $280 million dollars to Canadian society. Extended hospital stays and rehospitalizations accounted for the lion's share—92%—of the total. The 37 932 number of cases we estimated in Canada in 2012 was approximately 8% of the 453 000 estimated in the United States in 2011 [33], and the Canadian cost estimate of $280 million was approximately 9% of the $3.2 billion dollars per year in the United States [34], with both estimates nearly proportionate to the population sizes. For context, the estimated $272 million in direct medical costs represents 0.1% of the CAD $207 billion spent on healthcare in Canada in 2012.

The annual burden of illness is likely increasing due to the aging demographics of the population, leading to increased numbers of patients at risk, and the indiscriminate use of both antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors. From an economic perspective, hospital managers are often allocated inadequate funding for infection control because of a failure in budgetary mechanisms [35], the decentralization of budgets and responsibility, or uncertainty over the benefits of infection control [36]. Inadequate staffing, lower standards of hygiene in healthcare facilities, privatization of cleaning services, and overcrowding in hospitals have also been suggested as reasons why the number of C difficile infections in Canada have increased [32]. This burden will also potentially be affected by changing diagnostic practices with the expansion of new and more sensitive assays [37].

Given the high costs of hospitalization, preventing recurrence of C difficile is likely to lead to the largest reduction in direct medical costs by avoiding readmissions to hospital. Interventions that have been shown to reduce recurrence include the following: infection control measures; [36] reduced use of proton pump inhibitors which has been inferred based on 1.4- to 2.7-fold increase in risks of C difficile infections after observed use of these medications; [38] antimicrobial stewardship including removing concomitant systemic antibiotics and escalating antibiotic therapy when appropriate; [39] or the use of newly marketed antibiotics [13, 40]. While the technical and allocative efficiency of such programs and therapies is not yet adequately characterized in Canada, those that have the highest reduction in recurrence are likely to offer the highest value for money.

This study has important limitations. First, by comparing against data reported from Manitoba with the algorithm developed here, we noted a 9% underestimate in the number of C difficile infections. If this was the case in all provinces, the results reported here would underestimate the actual burden. Second, the estimated incremental hospital costs may have been confounded by the fact that hospitalized patients with C difficile infection had more comorbid medical conditions and longer lengths of stay than uninfected hospitalized patients. This was addressed by developing additional statistical models to adjust for health status unrelated to C difficile infection using the PHC Infection Prevention and Control dataset (available upon request). Third, we assumed that treatment followed the SHEA-IDSA guidelines [11], recognizing that this likely underrepresented the variability in treatment patterns between facilities in Canada. Fourth, the impact of excluding emerging therapies such as fecal transplant was low because use of new therapies is still rare in Canada. Fifth, costs that were excluded because of lack of data included: (1) Infection prevention and control procedures and services in hospitals (specifically, staffing levels of nurses, doctors, and epidemiologists in the infection prevention and control team, the proportion of those persons' time spent on infection surveillance and control, and the actual implementation and monitoring of prevention and control strategies) were excluded. Although potentially substantial, it would be challenging to validly allocate a proportion of these costs to C difficile because these procedures and services focus on all hospital-acquired infections; (2) No adequate data exist on lost productivity or on other direct medical and non-medical costs (such as caregiver burden). Lost productivity costs are challenging to quantify in a population such as this, which tends to have high levels of comorbidity and advanced age, and few people are able to return to paid work once they leave hospital, which would mean that using mean age-specific employment rates would inflate estimates of economic impact. On the other hand, there are serious equity implications of valuing lost time only among employed persons. Additional data collected via a patient or caregiver survey would be of value to quantify the magnitude of this burden. Finally, there were other potential, less influential sources of misclassification such as the use of clinical experts other than Public Health Agency of Canada Working Groups, interprovincial differences in costs, and others. We are confident that the results using different values of resource utilization or costs from these sources would be contained within the results sensitivity analyses presented.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights gaps in understanding the epidemiology and burden of C difficile, including the frequency and management in the community, robust estimates of incremental length of stay attributable to the infection, and costs of infection prevention and control programs and services in hospitals. Future studies can incorporate the information presented here to estimate the value of information of new research [41]. Understanding the relationship between recurrence and total costs, as well as the interplay among in-hospital, nursing home, and community-based costs, is critical for evaluating efforts designed to minimize the burden of C difficile infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author contributions. All authors contributed to the work presented here and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support. This work was funded by Cubist Pharmaceuticals (formerly Optimer), which manufactures fidaxomicin for Clostridium difficile. Three authors received direct compensation as a consultant to (A. R. L.), or employees of, ICON (S. M. S., G. L.-O.); and 1 author (R. L.) was an employee of Cubist Pharmaceuticals at the time this work was conducted.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

APPENDIX

Appendix Table 1.

Resource Use and Costs (2012 $CAD) Used to Estimate the Total Cost of Treating Clostridium difficile Infections in Canada, 2012

| Description | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Use | ||

| Incremental number of physicians visits for CDI in hospital | ||

| Internists or hospitalists, mild-to-moderate CDI | 2 | Assumption |

| Internists or hospitalists, severe CDI | 2 | Assumption |

| Radiologists, severe CDI | 1 | Assumption |

| Internists or hospitalists, fulminant CDI | 7 | Assumption |

| Infectious disease practitioners, fulminant CDI | 1 | Assumption |

| Radiologists, fulminant CDI | 1 | Assumption |

| General surgeons, fulminant CDI (for those requiring colectomy) | 2 | Assumption |

| Pathologists, fulminant CDI (for those requiring colectomy) | 1 | Assumption |

| Incremental number of physicians visits for CDI in community-based patients | ||

| General practitioners, mild- to-moderate CDI | 3 | Assumption |

| Infectious disease physicians, recurrent CDI | 1 | Assumption; 3 or 4 visits over 6 to 9 mo |

| Number of Interventions delivered to community-based C difficile patients | ||

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy; for multiple recurrent infections | 1 | Assumption |

| Flexible colonoscopy; for multiple recurrent infections | 1 | Assumption |

| Incremental number of healthcare contacts for CDI in long-term care | ||

| Nursing visits (per day) | 4 | Assumption |

| Personal support staff (per day) | 4 | Assumption |

| General practitioner/Hospitalist/Admitting physician (per week) | 1 | Assumption |

| Frequency of blood tests in long-term care | ||

| Complete blood count, white blood cell count, hematocrit | 1 | Assumption |

| Electrolytes | 1 | Assumption |

| Serum creatinine | 1 | Assumption |

| Albumin | 1 | Assumption |

| Proportion of the population that is used | ||

| 15 to 24 y | 0.55 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| 25 to 44 y | 0.81 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| 45 to 64 y | 0.71 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| 65 to 69 y | 0.23 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| ≥70 y | 0.06 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| Proportion of the working population considered full time | ||

| 15 to 24 y | 0.53 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| 25 to 44 y | 0.88 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| 45 to 64 y | 0.86 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| 65 to 69 y | 0.61 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| ≥70 y | 0.53 | Statistics Canada Labour force survey estimates |

| Costs | ||

| Cost of diagnostic testing for C difficile (2012 $CAD) | ||

| Polymerase chain reaction | 17.5 | Assumption |

| Toxin A/B enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay | 15.0 | Badger et al [42] |

| Standard culture with cytotoxin neutralization assay (cell/stool culture) | 5.0 | Badger et al [42] |

| Other tests (assumed glutamate dehydrogenase and toxigenic assay) | 12.0 | Badger et al [42] |

| Cost of physicians visits for CDI in hospital (2012 $CAD) | ||

| First visit, internist or hospitalist | 77.2 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| First visit, radiologist | 50.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| First visit, infectious disease practitioner | 157.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| First visit, general surgeon | 90.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| First visit, pathologist | 102.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Subsequent visit, internist or hospitalist | 58.8 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Subsequent visit, radiologist | 50.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Subsequent visit, infectious disease practitioner | 105.3 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Subsequent visit, general surgeon | 60.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Subsequent visit, pathologist | 102.0 | Ontario MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Costs of physicians visits for CDI in community-based patients (2012 $CAD) | ||

| General physician | 45.9 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Infectious disease physician | 157 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Costs of Interventions delivered to community-based C difficile patients (2012 $CAD) | ||

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | 116.29 | BC guide to fees 2010 [44] |

| Flexible colonoscopy | 251.23 | BC guide to fees 2010 [44] |

| Costs of healthcare contacts for CDI in long-term care (2012 $CAD) | ||

| Nursing visits | 34.13 | Median hourly wage, registered nurse in Canada; [45] |

| Support staff visits | 18.13 | Median hourly wage for a nurse aid in Canada; Canada [45] |

| Internist/General practitioner visits | 32.3 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Costs of blood tests in long-term care (2012 $CAD) | ||

| Complete blood count, white blood cell count, hematocrit | 7.8 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Electrolytes | 2.6 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Serum creatinine | 2.6 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Albumin | 2.6 | MOHLTC schedule of benefits [43] |

| Mean hourly wage (2012 $CAD) | ||

| 15 to 24 y | 13.6 | Statistics Canada: CANSIM tables 282-0069 and 282-0073 |

| 25 to 44 y | 25.5 | Statistics Canada: CANSIM tables 282-0069 and 282-0073 |

| 45 to 64 y | 25.2 | Statistics Canada: CANSIM tables 282-0069 and 282-0073 |

| 65 to 69 y | 24.9 | Statistics Canada: CANSIM tables 282-0069 and 282-0073 |

| ≥70 y | 24.9 | Statistics Canada: CANSIM tables 282-0069 and 282-0073 |

Abbreviations: BC, British Columbia; $CAD, Canadian dollars; CDI, Clostridium difficile infections; MOHLTC, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Appendix Table 2.

Parameter Estimates Used to Estimate the Total Cost of Treating Clostridium difficile Infections in Canada, 2012

| Model Input | Estimate | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| % New infection (of all infections) | 72.9 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % Reinfection (of all infections) | 6.3 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % First relapse (of all infections) | 15.7 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % Subsequent relapses (of all infections) | 5.1 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % infections <65 y | 30.0 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % infections 65 to <75 y | 16.0 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % infections ≥75 y | 54.0 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % treated in hospital | 52.7 | Khanna et al [22] |

| Number of infections in the community from LTC | 1604 | Khanna et al [22] |

| % of hospitalized patients with mild infection | 30.5 | Louie et al [13] |

| % of hospitalized patients with moderate infection | 30.2 | Louie et al [13] |

| % of hospitalized patients with severe infection | 39.2 | Louie et al [13] |

| % of hospitalized patients with fulminant infection | 2.1 | PHC IPAC dataset |

| % of community classified as infections | 20.0 | Khanna et al [22] |

| Number of vancomycin 125 mg pills dispensed, Canada, 2011 | 421 213 | BROGAN DATA; 2011 [25] |

| Number of vancomycin 250 mg pills dispensed, Canada, 2011 | 150 645 | Brogan Data [25] |

| Vancomycin (500 qid oral tab; daily cost) | $124.88 | Perras et al [46] |

| Metronidazole (500 mg IV; tid; daily cost) | $3.93 | Perras et al [46] |

| Metronidazole (500 mg oral tab; tid; daily cost) | $0.36 | Perras et al [46] |

| Incremental hospitalization cost, per initial infection, excluding pharmacotherapy cost | $11 928 | Predicted from PHC IPAC dataset |

| Incremental hospitalization cost, per relapse, excluding pharmacotherapy cost | $15 330 | Predicted from PHC IPAC dataset |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; PHC IPAC, Providence Health Care Infection Prevention and Control.

References

- 1.Gravel D, Miller M, Simor A et al. Health care-associated Clostridium difficile infection in adults admitted to acute care hospitals in Canada: a Canadian nosocomial infection surveillance program study. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:568–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996–2003. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:409–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redelings MD, Sorvillo F, Mascola L. Increase in Clostridium difficile-related mortality rates, United States, 1999–2004. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13:1417–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartman ST, Heap JT, Kuehne SA et al. The emergence of ‘hypervirulence’ in Clostridium difficile. Int J Med Microbiol 2010; 300:387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins DA, Hawkey PM, Riley TV. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in Asia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2013; 2:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warny M, Pepin J, Fang A et al. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet 2005; 366:1079–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He M, Miyajima F, Roberts P et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile. Nat Genet 2013; 45:109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitnis AS, Holzbauer SM, Belflower RM et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:1359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangen MJ, Plass D, Havelaar AH et al. The pathogen- and incidence-based DALY approach: an appropriate [corrected] methodology for estimating the burden of infectious diseases. PLoS One 2013; 8:e79740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31:431–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert PJ, Dyck M, Thompson LH, Hammond GW. Population-based surveillance of Clostridium difficile infection in Manitoba, Canada, by using interim surveillance definitions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30:945–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:422–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada. Labour Statistics CANSIM Tables 282-0069 and 282-0073. 2014; Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/labr69a-eng.htm. Accessed 2 July 2015.

- 15.Manitoba Health. Manitoba Monthly surveillance unit report. Public Health Disease Surveillance System, 2012. Available at: http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/scd/jan12.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Inpatient hospitalizations: volume, length of stay, and standardized rates. CIHI, 2012. Available at: http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/EN/Quick_Stats/quick+stats/quick_stats_main?xTopic=HospitalCare&pageNumber=2&resultCount=10&filterTypeBy=-undefined&filterTopicBy=5&autorefresh=1. Accessed 2 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Provincial Infection Control Network of British Columbia (PICNet). Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) surveillance report, April 1, 2010-March 31, 2011. British Columbia Provincial Health Services Authority, 2011; Available at: http://www.picnet.ca/uploads/files/CDI_Surveillance_Report_FY2010_11%20final.pdf Accessed 9 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Provincial Infection Control Network of British Columbia (PICNet). Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) surveillance report. Quarter 1 and quarter 2, 2011/2012. British Columbia Provincial Health Services Authority, 2012; Available at: http://www.picnet.ca/uploads/files/surveillance/CDI%20Surveillance%20Report%20semiannual%202011-2012%20Q1-2.pdf Accessed 26 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canadian Nocosomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP). Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea in acute-care hospitals participating in CNISP: November 1, 2004 to April 30, 2005. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2007; Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/pdf/c-difficile_cnisp-pcsin-eng.pdf Accessed 9 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simor AE. Clostridium difficile infection: Canadian Epidemiology, 2012. Clostridium difficile infection Prevention and Control Workshop, 2012. (May 28–29, 2012) Available at: http://www.oahpp.ca/resources/documents/presentations/2012may28-29/2.0%20-%20Epi%20Data/CdiffCanEpi2012.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2013.

- 21.Optimer Pharmaceuticals Inc. Baseline disease severity stratified by age group in mITT population. Optimer Pharmaceuticals Inc, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroentereol 2012; 107:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burman D. Findings from the hospital Clostridium difficile infection control survey. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2012. Available at: http://www.oahpp.ca/resources/documents/presentations/2012may28-29/4.0%20-%20Shift%20and%20Share%20Session/1.0%20-%20CDI%20Hospital%20and%20Health%20Unit%20Survey%20Findings/Hospital%20CDI%20survey%20Findings_DBurman_FINAL%2022May12.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vearncombe M. Laboratory testing for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the era of polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2012. Available at: http://www.oahpp.ca/resources/documents/presentations/2012may28-29/3.0%20-%20Laboratory%20Testing/CDI%20Laboratory%20Testing%20CDI%20Workshop%20May%202012.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.IMS Brogan. Provincial vancomycin claims data, 2010 to 2011. 2012.

- 26.Dubberke ER, Wertheimer AI. Review of current literature on the economic burden of Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forster AJ, Taljaard M, Oake N et al. The effect of hospital-acquired infection with Clostridium difficile on length of stay in hospital. CMAJ 2012; 184:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davison AC, Hinkley D. Bootstrap methods and their applications. Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics (No. 1), Cambridge, UK: 2006; 191–251. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumyati G, Stevens V, Hannett GE et al. Community-associated Clostridium difficile infections, Monroe County, New York, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: preventing Clostridium difficile infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepin J, Routhier S, Gagnon S, Brazeau I. Management and outcomes of a first recurrence of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:758–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoutman DE, Ford BD. A comparison of infection control program resources, activities, and antibiotic resistant organism rates in Canadian acute care hospitals in 1999 and 2005: pre- and post-severe acute respiratory syndrome. Can J Infect Control 2009; 24:109–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:825–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien JA, Lahue BJ, Caro JJ, Davidson DM. The emerging infectious challenge of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in Massachusetts hospitals: clinical and economic consequences. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28:1219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croxson B, Allen P, Roberts JA et al. The funding and organization of infection control in NHS hospital trusts: a study of infection control professionals' views. Health Serv Manage Res 2003; 16:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves N. Economics and preventing hospital-acquired infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:561–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honda H, Dubberke ER. The changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014; 30:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea can be associated with stomach acid drugs known as proton pump inhibitors PPIs). 2013; http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm290510.htm. Accessed 7 October 2013.

- 39.Valiquette L, Cossette B, Garant MP et al. Impact of a reduction in the use of high-risk antibiotics on the course of an epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated disease caused by the hypervirulent NAP1/027 strain. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(Suppl 2):S112–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Claxton KP, Sculpher MJ. Using value of information analysis to prioritise health research: some lessons from recent UK experience. Pharmacoeconomics 2006; 24:1055–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Badger VO, Ledeboer NA, Graham MB, Edmiston CE Jr. Clostridium difficile: epidemiology, pathogenesis, management, and prevention of a recalcitrant healthcare-associated pathogen. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2012; 36:645–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MOHLTC. Ontario Health Insurance (OHIP) Schedule of Benefits and Fees. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2012. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohip/sob/sob_mn.html. Accessed 7 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.British Columbia Medical Association. Guide to fees. British Columbia Medical Association, 2010. Accessed 7 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Government of Canada. Working in Canada. Government of Canada, 2012. Available at: http://www.workingincanada.gc.ca/home-eng.do?lang=eng. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perras C, Tsakonas E, Ndegwa S et al. Vancomycin or metronidazole for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection: Clinical and economic analyses. Technology report; no. 136 ed Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.