Abstract

Background

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare neuroendocrine tumor of the skin. MCC from an unknown primary origin (MCCUP) can present a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We describe our single-institution experience with the diagnosis and management of MCCUP presenting as metastases to lymph nodes.

Methods

After institutional review board approval, our institutional database spanning the years 1998–2010 was queried for patients with MCCUP. Clinicopathologic variables and outcomes were assessed.

Results

From a database of 321 patients with MCC, 38 (12%) were identified as having nodal MCCUP. Median age was 67 years, and 79% were men. Nodal basins involved at presentation were cervical (58%), axillary/epitrochlear (21%), or inguinal/iliac (21%). CK20 staining was positive in 93% of tumors tested, and all were negative for thyroid transcription factor-1. Twenty-nine patients (76%) underwent complete regional lymph node dissection (LND): 3 had LND alone, ten had LND and adjuvant radiotherapy, and 16 underwent LND followed by chemoradiotherapy. Definitive chemoradiotherapy without surgery was provided to six patients (16%), while radiotherapy alone was provided to three (8%). Recurrence was observed in 34% of patients. Median recurrence-free survival was 35 months. Ten patients (26%) died, five of disease and five of other causes. The median overall survival was 104 months.

Conclusions

Nodal MCCUP is a rare disease affecting primarily elderly white men. Recurrence is observed in approximately one-third of patients, with a 104 month median overall survival after a multimodal treatment approach consisting of surgery along with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the majority of patients.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin predominately affecting elderly white people. It commonly arises in sun-exposed areas such as the head, neck, and extremities.1 The incidence of MCC is very low when compared to other cutaneous malignancies, with an estimated 1,500 cases diagnosed annually within the United States.2–5 The clinical and pathologic diagnosis of MCC can be challenging, especially when it presents as nodal metastasis, because as a “small round blue cell tumor,” it can be difficult to differentiate from other undifferentiated small cell neoplasms of different primary origin, such as the lung.6 When patients present with clinically positive nodal disease in the absence of a history of an identifiable primary tumor and the tumor fulfills the diagnostic pathologic criteria, it is known as MCC of unknown primary origin (MCCUP).The incidence of MCCUP presenting in nodal basins has been described in small case reports in the literature as ranging 2–19% of all cases of MCC.7–10

Given the infrequency of this presentation, much of what has been reported on MCCUP has been limited to small case reports, and thus the exact incidence and outcome remains largely unknown. We present our experience on what is to our knowledge the largest series of patients undergoing treatment for nodal MCCUP reported to date.

METHODS

An institutional review board-approved, single-institution retrospective study of patients with a diagnosis of MCC and no known primary site who underwent evaluation from January 1998 to December 2010 was performed. Inclusion criteria for this report included patients who presented with biopsy-proven MCC in lymph nodes without a known history of a primary cutaneous lesion/tumor being removed and without previous diagnosis of MCC. Patients who presented with nodal MCCUP and had synchronous evidence of distant metastasis were excluded from this study. Patient demographics, clinicopathologic factors, treatment type, and clinical outcome were evaluated. All individual patient treatment decisions were made in conjunction with a weekly consensus multidisciplinary conference.

Patient Factors

Patient demographic data were obtained from the medical record from a detailed history and physical examination that was performed on each patient at the time of initial consultation to evaluate the patient for any signs or symptoms of a potential primary tumor. Whole-body positron emission tomography and/or computed tomographic imaging were performed to exclude metastatic disease.

Histologic Factors

All patients included in this analysis underwent histologic confirmation of MCCUP by review of pathology slides by a Moffitt Cancer Center dermatopathologist (J.L.M.). Immunohistochemical evaluation was performed on all tumors and included one or more of the following: broad-spectrum keratin (BSK), cytokeratin 7 (CK7), cytokeratin 20 (CK20), synaptophysin, thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), chromogranin A (CrA), and S100 protein. A diagnosis of MCCUP was made when a tumor was either positive for BSK or CK20 with a perinuclear dot–like pattern, or positive for CK20 (any pattern) along with a neuroendocrine marker such CrA, synaptophysin, or NSE, and also negative for TTF-1. TTF-1 staining was performed on all specimens available for immunohistochemical analysis. However, in certain instances (e.g., patients evaluated in the early years of the treatment cohort), additional staining was not possible because reference slides had to be returned to the referring pathology department and further immunohistochemical analysis was unable to be performed.

Treatment and Pathologic Factors

Patient treatment was defined as follows: complete lymph node dissection (LND) alone; LND plus radiotherapy; LND plus chemoradiotherapy; chemoradiotherapy without surgery; or radiotherapy alone. For patients who underwent LND, maximum tumor size (cm) and the total number of lymph nodes involved, as well as the absence or presence of extracapsular extension were noted. For patients treated with chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy alone, maximum tumor size was obtained from cross-sectional imaging or excisional biopsy, when available.

Outcome

Follow-up duration, recurrence-free survival (RFS), and overall survival (OS) were recorded from the date of diagnosis to the date of last clinical follow-up or death. Follow-up status was defined as follows: alive with no evidence of disease, alive with disease, dead of disease, or dead of other causes. Recurrence was identified as regional (within the original lymphadenectomy basin) or distant.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics for continuous variables and OS and RFS analyses were performed by SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data sampling distribution was examined and median result was reported when the distribution was skewed. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate median survival.

Results

During the study interval (1998–2010), a total of 321 patients underwent consultation or definitive treatment at Moffitt Cancer Center for primary or metastatic MCC; of these, 38 (12%) were identified as having MCCUP meta-static to lymph nodes and comprised the study population. No patient within the study population had a history of, or subsequently developed, a primary MCC tumor during the course of their treatment or follow-up. Median age was 67.0 (range 42–86) years, and 79% were men. MCCUP involved the head and neck lymph nodes in 58% of patients; the remainder had nodal disease involving axillary, epitrochlear, or inguinal/iliac basins.

Immunohistochemical and Pathologic Evaluation

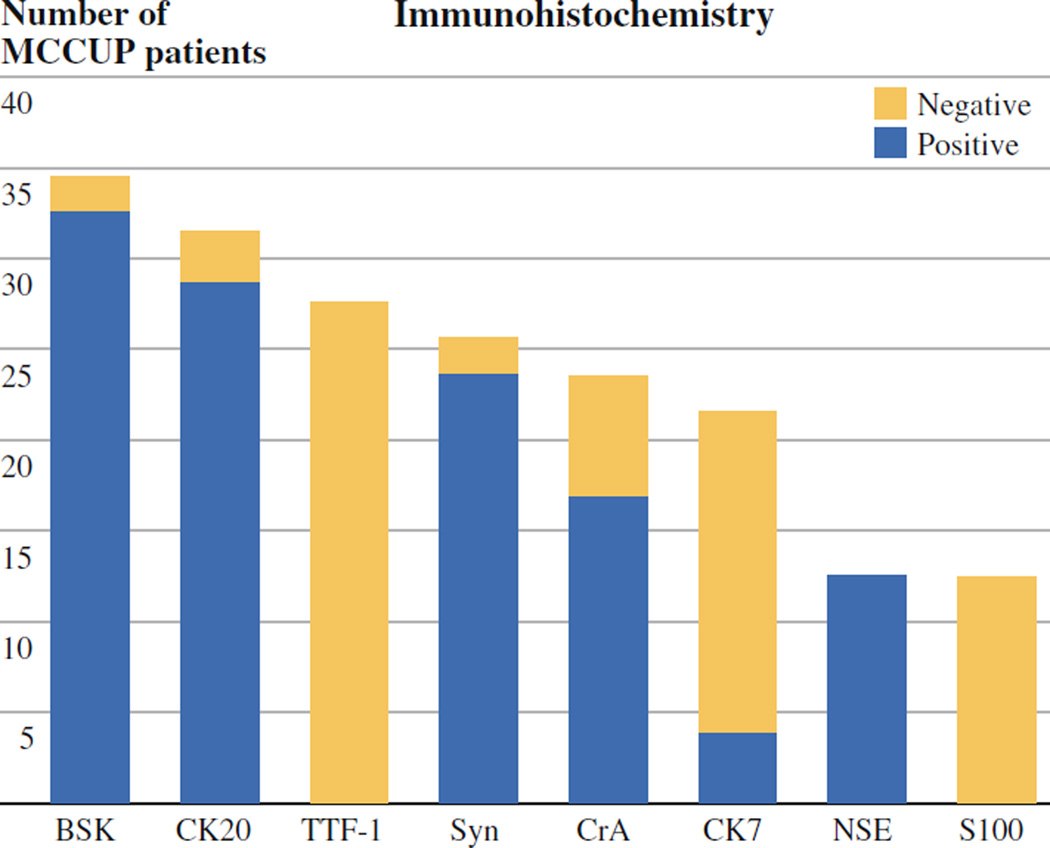

Ninety-seven percent of tumors tested were positive for BSK, and 93% of tumors tested were positive for CK20. Some tumors were positive for one or more additional neuroendocrine marker such as CrA, synaptophysin, or NSE, but these markers were far less sensitive, staining 58%, 63%, and 29% of tumors tested, respectively. All tumors tested for TTF-1 (n = 26) were negative (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Immunohistochemical staining features of all patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin

Maximum size of tumor-involved lymph nodes was available in 30 (77%) of 38 patients, with a median tumor size of 2.75 (range 0.3–13.0) cm. The median number of lymph nodes removed was 20 (range 1–67) in those patients who underwent LND (n = 29), with a median number of 1 (range 1–23) involved lymph node identified (mean 3.7 involved nodes). Twelve patients who underwent LND had more than one node involved with disease, while extracapsular extension was identified in 53% of patients on the basis of excisional biopsy or LND specimens (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic features for all patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (year), median (range) | 67 (42–86) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 8 (21%) |

| Male | 30 (79%) |

| Involved nodal basin | |

| Head/neck | 22 (58%) |

| Inguinal/iliac | 8 (21%) |

| Axillary/epitrochlear | 8 (21%) |

| Complete lymphadenectomy | |

| Yes | 29 (76%) |

| No | 9 (24%) |

| Lymphadenectomy location | |

| Head/neck | 20 (69%) |

| Inguinal/iliac | 6 (21%) |

| Axillary | 2 (7%) |

| Axillary + epitrochlear | 1 (3%) |

| Node size, cm, median (range) | 2.75 (0.3–13) |

| Total number of nodes removed, median (range) | 20 (1–67) |

| Number of involved nodes, median (range) | 1 (1–23) |

| Extracapsular extension (n = 23) | |

| Yes | 20 (87%) |

| No | 3 (13%) |

Treatment

Of the 38 patients included in this study, 29 (76%) underwent LND; the remainder were treated with radiotherapy alone (n = 3, 8%) or with chemoradiotherapy (n = 6, 16%) without surgery. Twenty patients underwent modified radical neck dissection, three patients underwent axillary lymphadenectomy, and six patients underwent inguinal or ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy. Of those patients who underwent LND, three patients (8%) were treated with surgery alone without further therapy, ten patients (26%) received adjuvant radiotherapy, and 16 patients (42%) were treated with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Chemotherapy was provided to a total of 22 (58%) patients with MCCUP in this series. Fifteen patients (68%) received a two-drug regimen, two patients (9%) received single-agent chemotherapy, and in five patients (23%), the chemotherapy regimen utilized was unknown. Etoposide (VP-16) with either cisplatin or carboplatin was used for combination chemotherapy, and cisplatin and carboplatin were each used in the two patients treated with single-agent chemotherapy. Most patients had chemotherapy after LND; however, six patients in our series (16%) underwent definitive treatment utilizing chemotherapy and radiotherapy without surgery. No patient received chemotherapy as the sole form of therapy (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Treatment and outcome factors for all patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| Surgery alone | 3 (8%) |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 10 (26%) |

| Surgery and chemoradiotherapy | 16 (42%) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 6 (16%) |

| Radiotherapy alone | 3 (8%) |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 13 (34%) |

| Location of recurrence (n) | |

| Regional | 4 |

| Distant | 9 |

| Median Recurrence-free survival (months) | 35 |

| Outcome, n (%) | |

| Alive | 28 (74%) |

| Dead | 10 (26%) |

| Patient status at last known follow up, n (%) | |

| ANED | 19 (50%) |

| AWD | 9 (24%) |

| DOC | 5 (13%) |

| DOD | 5 (13%) |

| Median Overall survival (months) | 104 |

ANED alive with no evidence of disease, AWD alive with disease, DOC dead of other cause, DOD dead of disease

Outcome

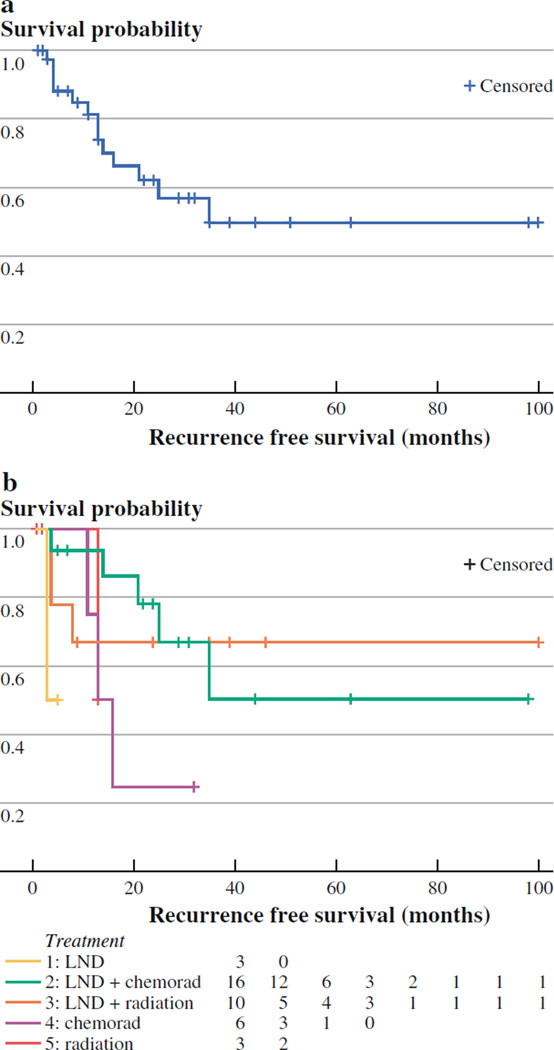

A description of patient outcomes based on treatment modality is provided in Table 3. A total of 13 (34%) of 38 patients experienced recurrence at any site. Of these 13 patients, 9 had distant recurrences, while the remaining 4 had regional recurrence in the same nodal basin as their MCCUP. No local recurrences that may have suggested a missed primary tumor were identified. Patients with regional recurrence had a shorter time to recurrence than those patients with distant recurrences (median of 4 months vs. 14 months, respectively). Eight of the 20 patients with pathologic evidence of extracapsular extension experienced disease recurrence, and in seven of these cases, the recurrences were distant in location. The median RFS for patients with MCCUP was estimated to be 35 months (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Outcome data based on treatment modality for all patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin

| Characteristic | Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LND alone (n = 3) |

LND + radiotherapy (n = 10) |

LND + chemoradiotherapy (n = 16) |

Chemoradiotherapy alone (n = 6) |

Radiotherapy alone (n = 3) |

|

| Median age (years) | 71 | 73.5 | 65 | 59 | 82 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 3 (100%) | 9 (90%) | 15 (94%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (33%) |

| Median tumor size in cm (range) | 3.2 (2–4.4) | 2.05 (0.3–13) | 2.8 (1.4–8) | 2.2 (2–5.5) | 5.0 (4–6.0) |

| Recurrence (n) % | 1 (33%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (31%) | 3 (50%) | 1 (33%) |

| Regional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Distant | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Median RFS (months) | – | – | – | 14.5 | – |

| First event (months) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 13 |

| Second event (months) | – | 4 | 14 | 13 | – |

| Third event (months) | – | 8 | 21 | 16 | – |

| Died, n (%) | 1 (33%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (17%) | 3 (100%) |

| DOD | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| DOC | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Median OS (months) | – | – | – | – | 20 |

| First event | 34 | 7 | 27 | 20 | 5 |

| Second event | – | 11 | 104 | – | 20 |

| Third event | – | 42 | – | – | 62 |

LND complete lymph node dissection, RFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

FIG. 2.

a Recurrence-free survival (RFS) for all patients treated for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of unknown primary origin. b RFS based on treatment for all patients treated for MCC of unknown primary origin

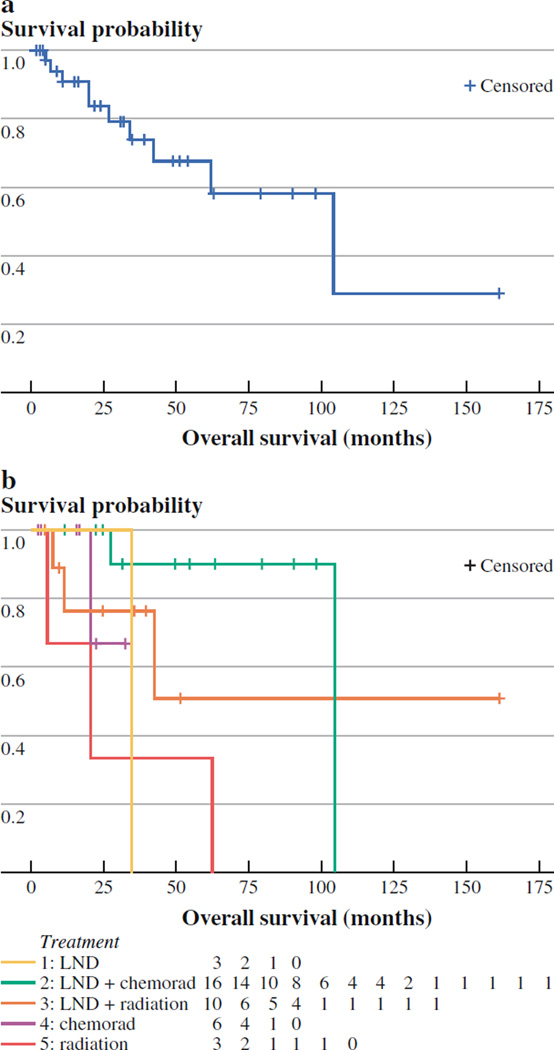

With a median follow-up of 25.1 months, a total of 28 patients (74%) were alive at last follow-up: 19 patients (50%) were alive with no evidence of disease, nine patients (24%) were alive with disease, and the remaining ten patients (26%) had died. Of the ten patients who died, five died of MCC-related causes and five died of other causes. Six of the 13 total patients who experienced recurrence during follow-up died, four of disease-related causes and two of other causes. Likely due to the small sample size, no patient-, tumor-, or treatment-related factors were found to be associated with worse survival by multivariate analysis. By the Kaplan-Meier method, the median OS time for all patients with MCCUP was estimated to be 104 months (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

a Overall survival (OS) for all patients treated for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of unknown primary origin. b OS based on treatment for all patients treated for MCC of unknown primary origin

DISCUSSION

MCC patients with nodal involvement who present without an identifiable primary tumor are infrequently encountered, even in centers that specialize in treating this rare disease. Although the exact incidence of MCCUP is unknown, we identified a higher percentage (12%) of patients who presented without an identifiable primary tumor from our comprehensive MCC database than initially expected. Heath et al. similarly reported on 27 patients who presented without an identifiable primary tumor of 195 patients (14%) treated for primary MCC.10 Given the paucity of published literature with limited clinical experience, theories regarding the exact origination of MCCUP remain unknown. MCCUP arising within a lymph node, extracutaneous sites, spontaneous regression of a primary MCC lesion, or association with immune suppression have all been suggested.11–14 The role of Merkel cell polyomavirus or MCC arising from a mucosal origin could also be contributing factors for the presentation and pathogenesis of MCCUP.15–17

Confirming the diagnosis of MCCUP requires immunohistochemical staining to exclude metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma from other sites of primary origin such as the lung.18 MCC is distinguishable from other potential sites of origin by negative staining for TTF-1 and positive CK20 staining with a characteristic perinuclear dot–like pattern of positivity.19,20 In contradistinction, neuroendocrine carcinoma metastatic from lung typically stains positive for TTF-1 and negative forCK20.21,22 In this series, 100%of those tested for TTF-1 (n = 26) stained negative, while 93% tested for CK20 stained positive. The remainder who were CK20 negative had expression of broad spectrum keratin plus another confirmatory neuroendocrine stain confirming diagnosis. Unfortunately, not all patients underwent testing for TTF-1 because outside pathology reference samples were not always available for review (e.g., patients evaluated early in the treatment cohort). In these situations, positive CK20 staining with another neuroendocrine marker (e.g., BSK, CrA, synaptophysin, NSE) was deemed to be sufficient for diagnosis. Other markers (e.g., CDX-2) were not routinely performed in the immunohistochemical assessment of a small blue cell tumor of unknown primary origin at our institution.

The treatment approach for patients with MCCUP was largely multimodal in nature in this series and varied between patients, with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy all being provided. Because the treatment groups were small in number, direct statistical comparisons were not significant between treatment groups; therefore, observational treatment and outcome data for each groups are reported (Table 3).

For primary MCC that is associated with clinically positive nodal disease (synchronous or metachronous) or those patients with positive sentinel node disease (occult nodal disease), we, and others, currently recommend complete dissection of the involved regional nodal basin.23,24 Three-quarters of the MCCUP patients in this series underwent complete LND for their nodal disease. With that being said, it is well known that MCC is radiosensitive and that adjunctive radiotherapy, provided to decrease locoregional recurrence in patients with bulky nodal disease or extracapsular extension, as definitive therapy for those patients medically unable to undergo surgical resection, or as definitive therapy in those with sentinel node-positive disease, are also a viable treatment alternatives to LND.25–28 Three patients in this series (8%) with MCCUP received definitive radiotherapy alone. Interestingly, these patients were older (median age 82 years) and had larger tumors (median 5.0 cm) than the other treatment groups.

Adjuvant chemotherapy has historically had a more limited role in treating these patients and has not demonstrated an improvement in OS.29,30 We observed a better overall outcome (Table 3; Fig. 3b), however, when adjuvant chemotherapy was combined with surgical lymphadenectomy followed by radiotherapy. This cohort comprised the majority of patients treated in this series. These patients tended to be younger and presumably more likely to tolerate radical lymphadenectomy followed by an aggressive multidisciplinary regimen. Regional and distant recurrences were highest in this treatment group, but so also was OS (only one patient died of disease-related causes). Although it is difficult to draw any lasting conclusions on the basis of such small treatment groups, these results do suggest the potential for acceptable outcomes by using a multimodal treatment approach.

Recurrences were observed in 34%(n = 13) in this series, a majority of which were distant (n = 9) in nature. This overall recurrence observation for MCCUP aligns with what is reported in the literature for primary MCC. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reported an overall recurrence of 30% (108 of 364 patients) for those with stage I–III MCC.31 Clinically involved lymph nodes, along with primary tumor lymphovascular invasion and history of lymphoma/leukemia, were found to be predictive of recurrence. In the current series, the median RFS was only observed in one treatment group (chemoradiotherapy group; three of six experienced recurrence), with all other groups not reaching the median at the time of this publication. Further follow-up and larger cohorts would be required to determine whether there is truly a beneficial treatment-related effect that may have accounted for the observed small differences in recurrence rates seen in the current study.

For primary MCC, outcome is primarily based on the stage at presentation, with both increasing tumor size and lymph node positivity being associated with a worse prognosis.5,32 One could assume, therefore, that given the regional presentation of positive nodal disease, patients with MCCUP would also tend to fare worse. In our current experience, however, this was not the case. The final outcome was generally favorable, with almost three-fourths of patients alive at follow-up. A recent report on 500 patients with MCC treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center identified that patients who presented with metastatic (stage 4) or clinically node-positive lymph nodes (stage 3b) had a worse disease-specific death than those with microscopically positive lymph nodes (stage 3a) or clinically node-negative patients (stage 1 or 2).33 Although we did not perform a direct comparison with node-positive patients of similar disease stage, our results for MCCUP were empirically better than anticipated, as the median survival time was estimated at 104 months with a 4 year OS of 68% (Fig. 3a). Others have similarly recently suggested that stage IIIB MCC patients with an occult primary tumor have better OS, disease-free survival, and relapse-free survival than those without an occult primary tumor.34 As with RFS, the median OS was only observed in one treatment group (radiotherapy alone, 20 months).However, those treated with lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy had longer observed OS than any other treatment group. Whether this observation was attributable to selection of a younger, healthier patient population for a more aggressive multimodal treatment approach alone is unknown and would require further follow-up before drawing any lasting conclusions.

The small sample size and retrospective nature reporting on this rare disease and its presentation highlight several of the limitations of the current study. There is both a referral bias and a selection bias in that patients who presented with more advanced disease, who presented with unresectable tumors, or who had medical comorbidities prohibiting surgical consideration may have been far more likely to undergo medical therapy preferentially over surgical lymphadenectomy. Equally important, although this work is primarily descriptive, a direct comparison with stage-similar MCC patients with known primary tumors is required (and currently underway at our institution) to better define this population and its outcome.

In conclusion, MCCUP is a rare disease affecting primarily elderly white men. Several treatment alternatives exist and should be selected on an individual basis with a multidisciplinary consensus. Recurrence is observed in approximately one-third of patients with a 104-month median OS after a multimodal treatment approach consisting of surgery along with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in most patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Angela M. Reagan for her contributions to the preparation of the article.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2011 Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Meeting, San Antonio, TX, March 5, 2011.

DISCLOSURES None

REFERENCES

- 1.Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan D, Narayan D, Ariyan S. Merkel cell carcinoma: five case reports using sentinel lymph node biopsy and a review of 110 new cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1259–1265. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000025287.96915.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koljonen V. Merkel cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemos B, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma: more deaths but still no pathway to blame. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2100–2103. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edge SB, editor. Merkel cell carcinoma. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, Heslin MJ, Bland KI, Beenken SW. Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1,024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:204–208. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veness MJ, Perera L, McCourt J, Shannon J, Hughes TM, Morgan GJ, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: improved outcome with adjuvant radiotherapy. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tai PT, Yu E, Winquist E, Hammond A, Stitt L, Tonita J, Gilchrist J. Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine/Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: case series and review of 204 cases. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2493–2499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, Sagy N, Schwartz AM, Henson DE, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, Lorè B, Iannetti G, Sardella B, et al. Total spontaneous regression of advanced Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:815–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Val-Bernal JF, Garcia-Castano A, Garcia-Barredo R, Landeras R, De Juan A, Garijo MF, et al. Spontaneous complete regression in Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:174–177. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31820ce11f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muirhead R, Ritchie DM. Partial regression of Merkel cell carcinoma in response to withdrawal of azathioprine in an immunosuppression-induced case of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19:96. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mir R, Sciubba JJ, Bhuiya TA, Blomquist K, Zelig D, Friedman E. Merkel cell carcinoma arising in the oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:71–75. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snow SN, Larson PO, Hardy S, Bentz M, Madjar D, Landeck A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin and mucosa: report of 12 cutaneous cases with 2 cases arising from the nasal mucosa. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:165–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCardle TW, Sondak VK, Zager J, Messina JL. Merkel cell carcinoma: pathologic findings and prognostic factors. Curr Probl Cancer. 2010;34:47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linjawi A, Jamison WB, Meterissian S. Merkel cell carcinoma: important aspects of diagnosis and management. Am Surg. 2001;67:943–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iacocca MV, Abernethy JL, Stefanato CM, Allan AE, Bhawan J. Mixed Merkel cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:882–887. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ordonez NG. Thyroid transcription factor-1 is a marker of lung and thyroid carcinomas. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7:123–127. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200007020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hitchcock CL, Bland KI, Laney RG, 3rd, Franzini D, Harris B, Copeland EM., 3rd Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin. Its natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Surg. 1988;207:201–207. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198802000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messina JL, Reintgen DS, Cruse CW, Rappaport DP, Berman C, Fenske NA, et al. Selective lymphadenectomy in patients with Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:389–395. doi: 10.1007/BF02305551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen PJ, Busam K, Hill AD, Stojadinovic A, Coit DG. Immunohistochemical analysis of sentinel lymph nodes from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:1650–1655. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1650::aid-cncr1491>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veness M, Foote M, Gebski V, Poulsen M. The role of radiotherapy alone in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: reporting the Australian experience of 43 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao NG. Review of the role of radiation therapy in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2010;34:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howle JR, Hughes TM, Gebski V, Veness MJ. Merkel cell carcinoma: an Australian perspective and the importance of addressing the regional lymph nodes in clinically node-negative patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.029. In press. Epub ahead of print 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez RJ, Padhya TA, Cherpelis BS, Prince MD, Aya-Ay ML, Sondak VK, et al. The surgical management of primary and metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2010;34:77–96. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I, Walpole E, Harvey J, Hamilton C, et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudchadkar R, Deconti R. Systemic treatments for Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2010;34:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, Panageas KS, Pulitzer MP, Allen PJ, et al. Recurrence after complete resection and selective use of adjuvant therapy for stage I through III Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26626. (in press). Epub ahead of print 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Busam K, Coit DG. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300–2309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, Panageas KS, Pulitzer MP, Allen PJ, et al. Five hundred patients with Merkel cell carcinoma evaluated at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2011;254:465–473. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c5fc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foote M, Veness M, Zarate D, Poulsen M. Merkel cell carcinoma: the prognostic implications of an occult primary in stage IIIB (nodal) disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.09.009. (in press). Epub ahead of print 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]