Abstract

Background

Major amputations are indicated for advanced tumors when limb-preservation techniques have been exhausted. Radical surgery can result in significant palliation and possible cure.

Methods

We identified 40 patients who underwent forequarter (FQ) or hindquarter (HQ) amputations between May 2000 and January 2011. Patient demographics, tumor-related factors, and outcomes were reviewed.

Results

There were 30 FQ and 10 HQ amputations. The most common diagnoses were sarcoma (55%) and squamous cell carcinoma (25%). Patients presented with primary tumors (35%), regional recurrence (57.5%), or unresectable limb metastatic disease (7.5%). Presenting symptoms included fungating wounds (35%), intractable pain (78%), and limb dysfunction (65%). Operations were performed with curative intent (10%), curative/palliative intent (70%), or palliation alone (20%). Wound complications occurred in 35%. Pain was improved in 78% of patients following surgery. Despite a 91% negative margin rate, 79% of patients recurred either locally or distantly. Median overall survival was 10.9, 13.2, and 3.4 months in the curative, curative/palliative, and palliative groups, respectively.

Conclusions

In the absence of conservative options, major amputations are indicated for the management of advanced tumors. These operations can be performed safely, resulting in effective palliation of debilitating symptoms. While recurrence rates remain high, some patients can achieve prolonged survival.

Keywords: amputation, forequarter, hindquarter, extremity tumor

INTRODUCTION

The earliest reports of radical extremity amputations date back to the 1800s. Ralph Cuming, a young surgeon at the Naval Hospital in Antigua, is credited with performing the first forequarter (FQ) amputation on a patient for a gunshot wound in 1808 [1]. Few details of the experience were recorded, although it is believed that the patient survived the procedure and recovered within a few months. In 1836, Dixi Crosby [2] performed the first FQ amputation for malignant disease at Dartmouth Medical College. The patient had an osteosarcoma weighing 25 pounds. He survived the surgery and two additional operations for local recurrence before succumbing to metastatic disease 2 years later. In 1891, Theodor Billroth performed the first hindquarter (HQ) amputation for a soft tissue sarcoma, although the patient died within hours due to shock [3]. Through the late 1800s and early 1900s, radical amputations for malignancy underwent a number of technique modifications. For several decades, amputation was the standard of care for the treatment of advanced extremity tumors.

In the era of multimodality therapy, radical resection of extremity tumors has been replaced by conservative surgical techniques that aim to preserve limb function. An example of this paradigm shift is seen with the management of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Thirty years ago, amputation was the primary treatment for nearly 50% of extremity sarcomas [4,5]. Increasingly effective radiation and chemotherapy protocols, combined with improved surgical techniques, have reduced the rate of amputation for primary tumors to approximately 5% [6]. Even in the setting of recurrent disease, amputation rates are frequently under 15%, owing to the success of salvage surgery [7]. Thus, limb preservation has become the standard of care for advanced extremity tumors.

Unfortunately, some patients present with disease that is not amenable to conservative surgical management. Tumors invading proximal nerves and vessels often make limb preservation impossible, leaving a radical amputation as the only surgical option and the only chance for long-term survival. The indications for proximal amputation are well described and include intractable pain, neurovascular compromise, fungating growth, and the inability to maintain limb function with complete resection [8–12]. Amputation of the affected extremity can result in palliation of these tumor-related complications. Furthermore, reports of long-term survival support the indication for aggressive surgery in the absence of effective alternative options [3,13,14]. However, these procedures can be associated with significant morbidity, leading some to question the benefit of this extreme approach in these patients with a uniformly poor prognosis.

In this review, we report our experience with radical resection of proximal extremity tumors, including complications, survival rates, and the palliative potential of surgery in these complicated oncologic situations.

METHODS

After obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, we identified 40 patients who underwent FQ and HQ amputations at Moffitt Cancer Center between May 2000 and January 2011. Clinical and pathologic variables were gathered through retrospective review of medical records. Patients were analyzed by tumor type, extent of disease, and intent of surgical intervention (curative, curative/palliative, palliative). Patients in the curative group presented with proximal extremity tumors or advanced regional disease without debilitating symptoms. Patients in the curative/palliative group had regional disease causing intractable pain, loss of limb function, and/or fungating wounds without evidence of systemic metastases. They were taken to the operating room for palliation of these symptoms, and in the absence of distant disease they had a chance for cure. Lastly, those in the palliative group presented with known metastatic disease; however, each patient suffered from intractable pain, loss of function, and/or fungating wounds that could not be controlled by conservative measures. Surgical resection was indicated for the treatment of these tumor-related symptoms.

Postoperative complications were recorded and stratified by the type of procedure (HQ vs. FQ). Symptom relief was subjectively determined by reviewing the postoperative clinic notes. Recorded data was updated through May 2011. Disease-free survival (DFS) and postoperative overall survival (OS) were calculated from the time of surgery to the last follow-up or date of death. When lost to follow-up, the date of death was obtained using the social security death index if available. Using SPSS 19 statistical software (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), the DFS and OS rates were estimated by means of the Kaplan–Meier method.

RESULTS

Forty patients underwent 30 FQ amputations and 10 HQ amputations. There were 23 males and 17 females; median age at the time of surgery was 62 years (range, 16–84 years). The primary diagnoses included sarcoma (n = 22: 18 soft tissue, 4 osteosarcoma), squamous cell carcinoma (n = 10: 6 cutaneous, 1 anal, 1 penile, 1 vocal cord, 1 unknown), melanoma (n = 4), breast cancer (n = 2), lung cancer (n = 1), and endometrial cancer (n = 1). Regarding the extent of disease, 35% of patients presented with primary tumors of the proximal extremity, 57.5% with regional recurrence in the groin, axilla, or proximal extremity, and 7.5% with metastases to the affected limb from a distant primary site (Table I).

TABLE I.

Distribution of Clinicopathologic Characteristics of 40 Patients Undergoing FQ and HQ Amputations

| FQ, no. (%) | HQ, no. (%) | Total, no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Patients | 30 (75) | 10 (25) | 40 |

| Age, median (range) | 62 (16–84) | 62 (41–79) | 62 (16–84) |

| Sex | |||

| M | 18 (60) | 5 (50) | 23 (57) |

| F | 12 (40) | 5 (50) | 17 (43) |

| Tumor type | |||

| Sarcoma | 14 (47) | 8 (80) | 22 (55) |

| SCC | 8 (27) | 2 (20) | 10 (25) |

| Melanoma | 4 (13) | — | 4 (10) |

| Breast | 2 (7) | — | 2 (5) |

| Lung | 1 (3) | — | 1 (2.5) |

| Endometrial | 1 (3) | — | 1 (2.5) |

| Type of disease | |||

| Primary | 11 (37) | 3 (30) | 14 (35) |

| Regional recurrence | 16 (53) | 7 (70) | 23 (57.5) |

| Metastatic | 3 (10) | — | 3 (7.5) |

Clinical Presentation

Upon presentation, 14 (35%) patients had fungating wounds due to tumor infiltration through the skin (example in Fig. 1), 31 (78%) patients had intractable pain that was poorly managed with standard medications, and 26 (65%) patients had a dysfunctional limb with paralysis or massive edema due to neural and/or vascular compromise.

Fig. 1.

Extreme example of a patient with locally advanced sarcoma causing extensive soft tissue destruction.

Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation

Neoadjuvant therapy was used in 34 (85%) patients: 6 patients (15%) received chemotherapy, 7 patients (17%) underwent radiation therapy, and 21 patients (53%) received both chemo- and radiation therapy prior to surgery.

Surgical Resection

Surgery was performed with curative intent in four (10%) patients, with curative/palliative intent in 28 (70%) patients, and for palliation alone in 8 (20%) patients (Table II). One patient with recurrent melanoma presented with sepsis due to an infected axillary mass. He underwent urgent FQ amputation, but died 6 days later from multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, resulting in a 2.5% (1 of 40) operative mortality rate in this patient population.

TABLE II.

Therapeutic Intent for Patients Undergoing FQ and HQ Amputations

| FQ, no. (%) | HQ, no. (%) | Total, no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Patients | 30 | 10 | 40 |

| Cure | 4 (13) | — | 4 (10) |

| Palliation + cure | 21 (70) | 7 (70) | 28 (70) |

| Fungating wound | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Intractable pain | 18 | 5 | 23 |

| Limb dysfunction | 17 | 1 | 18 |

| Palliation | 5 (17) | 3 (30) | 8 (20) |

| Fungating wound | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Intractable pain | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Limb dysfunction | 5 | 3 | 8 |

Surgical Complications

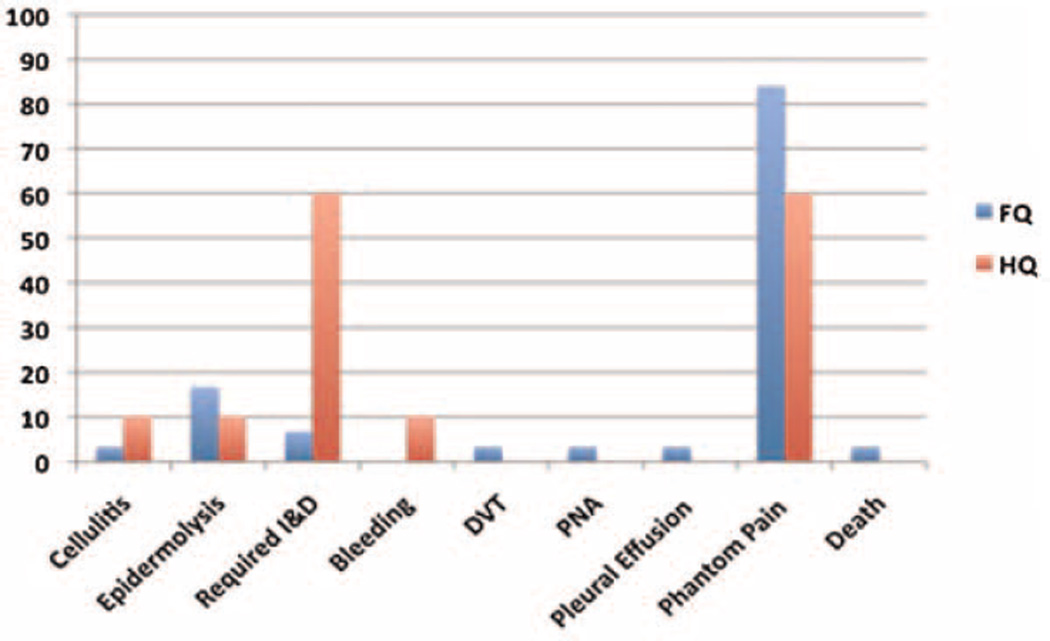

The median postoperative follow-up was 9.2 months (range, 0.2–56). Wound complications including cellulitis, abscess, and flap necrosis occurred in 35% (14 of 40) of patients. Eight patients required operative debridement of their surgical wound for infection or flap necrosis. The majority (75%) of these were in the HQ amputation group. Notably, six of the eight patients requiring surgical debridement initially presented with fungating wounds, putting them at increased risk for surgical site infection. Ultimately, all patients who presented with fungating wounds achieved complete surgical wound healing. Other postoperative complications including postoperative bleeding, DVT, pneumonia, and pleural effusion were uncommon (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Incidence (percentage) of postoperative complications in 40 patients undergoing FQ and HQ amputations.

Postoperative Outcomes and Survival

Intractable pain was a presenting symptom in 78% (31 of 40) of the patients. Of these 31 patients, postoperative pain could be controlled with oral pain medications in 78% (21 of 27) following surgery. Outcomes regarding pain control were unable to be determined for three patients due to lack of detail in the clinical records, while the fourth patient was the perioperative death.

Phantom pain is a common phenomenon described after extremity amputation [15]. We included phantom pain in our analysis of postoperative complications. The overall incidence of phantom pain in 35 evaluable patients undergoing FQ and HQ amputations was 84% and 60%, respectively (Fig. 2). The majority of these cases were effectively managed by a dedicated pain/palliative care service. However, 8 of 35 (23%) patients developed severe phantom pain that was poorly controlled with standard medications. Six of these patients had preoperative intractable pain, while two patients were in the curative group and had no antecedent history of pain.

Surgical margins were negative in 91% (29 of 32) of the operations performed in the curative and curative/palliative intent groups. Excluding one patient lost to follow-up, recurrence developed in 79% (22 of 28) of patients with a margin-negative resection. Local recurrence was seen in 36% (10 of 28) of patients with a complete resection, while distant recurrence occurred in 43% (12 of 28). When looking at recurrence by tumor type after margin-negative resection: 74% (14 of 19) of the sarcomas and 100% (7 of 7) of the squamous cell carcinomas recurred (Fig. 3). The median DFS for all patients was 6.4 months (1–44). Resection of sarcomas carried the longest DFS at 6.6 months (2–34), while median time to local or distant recurrence was 2.9 months (1–44) for squamous cell carcinoma. One breast cancer patient with a negative-margin resection recurred distantly after 4 months, while one melanoma patient recurred locally within 2 months.

Fig. 3.

Rate (percentage) and site of recurrence in curative and curative/palliative patients following margin-negative amputation for sarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

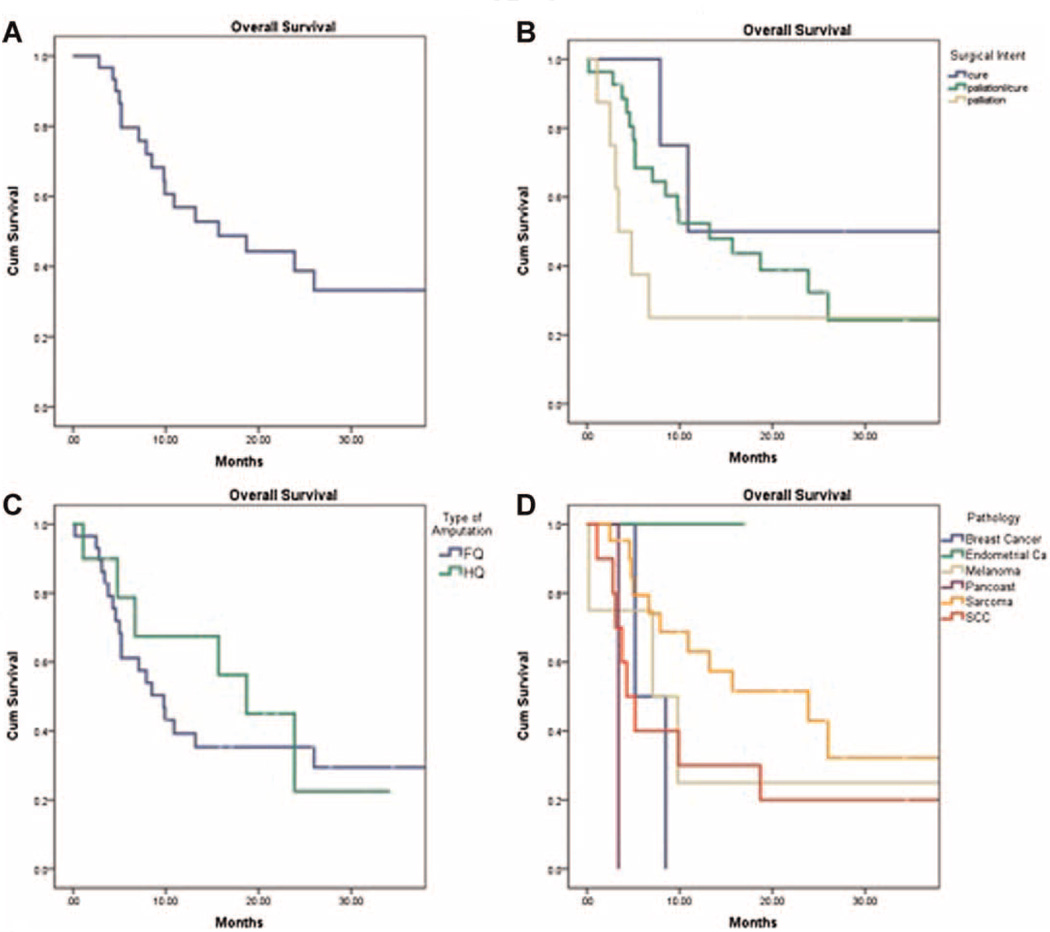

The median OS for this patient population was 10.9 months (Fig. 4A). By surgical intent, the median OS was 10.9 (8–56), 13.2 (3–53), and 3.4 (1–39) months in the curative, curative/palliative, and palliative groups, respectively (Table III and Fig. 4B). HQ amputations had a better median OS of 18.7 months compared to 9.8 months in the FQ amputation group (Fig. 4C). This is likely due to the prevalence of sarcomas in the HQ group. When comparing tumor types, sarcoma patients had the longest median OS at 23.9 months (3–56), followed by melanoma (7.1 months, 7–39), breast (5.2 months, 5–9), and squamous cell carcinoma (4.3 months, 1–53) (Fig. 4D). The patient with metastatic endometrial cancer who underwent FQ amputation for palliation of a painful, dysfunctional limb is alive over 17 months after surgery. The patient with a Pancoast tumor undergoing FQ amputation for palliation died from pneumonia 3 months after surgery following a difficult postoperative course.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves illustrating overall survival based on the (A) total study group, (B) surgical intent, (C) type of amputation, and (D) tumor type.

DISCUSSION

Over the past 50 years, several institutions have published case reports and small series on radical amputations for cancer [8,16–24]. Authors describe their experiences with FQ and HQ amputations in regards to local control of disease, overall survival, palliation of disabling symptoms, and quality of life [3,7,10,19,25–28]. The aim of this study was to determine our institutional outcomes and to compare the experience with others.

A wide spectrum of pathology is represented in our patient population. The majority of patients had sarcoma (55%, 10 subtypes), 25% had squamous cell carcinoma (4 subtypes), and the remainder of the cases included melanoma, breast, lung, and endometrial cancer. Others have reported similar pathologic diversity in the setting of major amputation. While primary bone and soft tissue sarcomas are the most common tumors requiring radical resection, several reports of proximal amputations for squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, breast cancer, and radiation-induced sarcoma have been published [8,10,20,25–27,29–31]. Daigeler et al. [32] published a review of 45 patients undergoing FQ or HQ amputations for several subtypes of sarcoma (n = 37), squamous cell carcinoma (n = 5), Merkel cell carcinoma (n = 1), breast carcinoma (n = 1), and lung carcinoma (n = 1). Over 60% of these patients had metastatic disease and were treated for palliation of disabling pain and fungating wounds. While complication rates were high (44%) and survival was low (43% at one year), the authors reported significant improvements in quality of life, highlighting the role for proximal major amputation in carefully selected patients.

Historically, radical amputations have been viewed as significantly morbid operations. In the early 1900s, mortality rates for major amputations exceeded 50% [24]. Over the ensuing decades, advances in anesthesia and surgical technique have greatly improved the safety profile. The operative mortality rate in our series is 2.5%, with the single death occurring in a patient who presented with sepsis. In general, reported mortality rates following radical amputations have been reduced to 0–10% [3,25,27,29,33,34]. However, these procedures continue to be associated with significant morbidity. The incidence of complications following HQ amputations ranges from 50% to 80% [18,29,35]. Complication rates following FQ amputation are generally lower [12,25,31]. Most postoperative complications are due to wound infection and flap necrosis. In our series, 35% of patients developed a wound complication, many of which required operative debridement. Most of these occurred in the HQ amputation group. Two-thirds of those taken back to the operating room had originally presented with open, fungating wounds. Thus, these were Class IV/dirty-infected cases that carry a high risk of postoperative surgical site infection. In addition, the proximity of the lower extremity and pelvic tumors to the perineum and groin poses another risk factor for infection. Other wound complications were successfully managed with conservative measures. All wounds eventually healed without chronic care needs.

When looking at all procedures and tumor types combined, the median OS in our population was 10.9 months. Of note, 35% (14 of 40) of the patients were alive at the time of the analysis. HQ amputations had the better median OS of 18.7 months. This is likely due to the fact that 80% of the HQ amputations were for sarcoma, a tumor type that demonstrated the longest survival. FQ amputations, which included more diverse pathology, had a median survival of 9.8 months.

We included a unique classification of surgical intent in an effort to stratify patients based on the extent of disease and presence of symptoms at presentation. The majority of our patients (70%) were considered to be in the curative/palliative group. Patients in the curative intent group had a median postoperative survival of 10.9 months, compared to the curative/palliative group who had a median postoperative survival of 13.2 months. Median OS in the palliative intent group was expectantly lower at 3.4 months, although two of these eight patients remain alive at 17 and 39 (endometrial and melanoma) months following surgery. This suggests that even in the setting of advanced disease, palliation and prolonged survival can be achieved.

In the literature, survival outcomes following radical amputation for many different tumors have been reported in a variable fashion, making it difficult to compare studies. For published series on FQ amputations, overall 5-year survival ranges from 20% to 40% [19,20,25,31]. When looking at HQ amputations, reports of 5-year survival vary between 10% and 83% depending on the type of tumor and the surgical intent [3,8,29,34]. One should use caution when interpreting reported survival rates in heterogeneous groups of patients with tumors that have a variable propensity to spread distantly. While we included Kaplan–Meier curves to illustrate the survival patterns observed in our patient population, by no means was this intended to make statistical comparisons between patient subsets.

The impact of local disease control on outcomes has been controversial. Local recurrence rates following FQ and HQ amputations range from 18% to 36% [26,28,31,32,35–37]. Some have shown that achieving local control can have a beneficial impact on survival [38–40]. Others, however, have reported data showing no benefit, with the rates of metastatic disease overshadowing rates of local recurrence [41–43]. In our study, surgical margins were negative in 91% of our patients following potentially curative amputation. Despite a satisfactory negative margin rate in this setting, 43% of the patients developed local recurrence. This value is slightly higher than other published series [8,11,14,27,31]. There was a notable difference in local recurrence among tumor types, as 57% of squamous cell carcinomas recurred locally, while only 21% of sarcoma patients developed local recurrence. Local control of disease should be considered a principle goal of surgery in this patient population. If not for a possible survival advantage, it can improve quality of life by alleviating the devastating effects of local invasion [11,31].

In a review by Williard et al. [43], tumors requiring amputation for resection of gross disease are associated with a higher incidence of distant metastases, which in turn predicts worse overall survival. Their study looked only at soft tissue sarcomas, while our patients had a variety of tumor types. Distant recurrence was seen in 43% of our patients following amputation for possible cure. Fifty-three percent of sarcomas and 43% of squamous cell carcinomas developed metastatic disease, primarily in the lungs. This is consistent with other studies that have reported rates of distant recurrence in the range of 17–66% [8,29,37]. Some reports have noted higher rates of distant disease in squamous cell carcinomas when compared to sarcomas. Baliski et al. looked at 13 patients undergoing hemipelvectomy for sarcoma and carcinoma. The sarcoma patients had 86% DFS at 12 months, while 4 out of 6 patients with carcinoma developed distant disease within 9 months. They concluded that hemipelvectomy is potentially curative in sarcomas, while in carcinomas the surgery was not curative [29]. Reviewing these outcomes reminds us that despite an aggressive surgical approach, prognosis is often predicated on the biology of the tumor.

In the setting of advanced malignancy, surgery in the palliative setting is performed for symptom relief with little prospect in prolonging survival. Our patient population is a good example of when palliative care becomes a primary therapeutic goal. Ninety percent of our patients presented with debilitating symptoms (example in Fig. 5). While surgery offered a chance for cure for many patients with regional disease, the decision for radical resection was largely driven by the desire to obtain relief of symptoms. Due to the retrospective nature of our study, it is difficult to assess the degree of symptom relief following major amputation. Furthermore, no formal quality of life assessment was performed. We looked at malignant wounds, intractable pain, and limb dysfunction as preoperative indications for palliative surgery. Amputations that relieved patients of these presenting conditions were considered to be a success. As noted, fungating tumors were effectively treated with radical surgical intervention, allowing patients to live out the remainder of their lives without having to suffer with chronic wounds. In terms of intractable pain, we were able to improve pain control in the vast majority (78%) of affected patients.

Fig. 5.

Forty-nine-year-old woman with recurrent left breast cancer. Salvage chemotherapy and radiation therapy had only a transient response. The tumor progressed, encasing the neurovascular bundle and causing debilitating pain, swelling, and limb dysfunction. A,B: Coronal and axial MRI images of the tumor involving the clavicle, chest wall, brachial plexus, and subclavian vessels. C: Deltoid fasciocutaneous flap following forequarter amputation. The first and second ribs were resected en bloc and the chest wall was reconstructed with mesh. D: Closure of the deltoid fasciocutaneous flap. E,F: Postoperative results at 2 weeks. The patient had significant improvement in her pain.

Phantom pain is a common problem following amputation, particularly in patients presenting with severe pre-amputation pain [44]. Inconsistencies in defining phantom pain or phantom sensation have led to a wide range (0–100%) of incidences reported in the literature [32,45]. Various strategies to reduce this phenomenon have been described, although no single method has shown consistent benefit [45–49]. In our study, we carefully reviewed postoperative clinic notes to ascertain the incidence of phantom pain. In this patient population, 77% of patients with medical records detailing their postoperative pain described some degree of phantom pain. The majority of these patients had mild to moderate phantom pain that was successfully managed by our institutional pain/palliative care team with routine follow-up. Seventy percent of patients with phantom pain suffered from intractable pain preoperatively. Review of the medical records indicated that 77% of these patients had an overall improvement in their pain control following surgery. There was a subset of patients (23%, 8 of 35) who underwent amputation and developed severe phantom pain that was refractory to standard regimens. Unfortunately, two of these patients had no disabling preoperative symptoms, but instead were undergoing curative FQ amputations for soft tissue sarcoma. While significant relief of preoperative malignant pain can be achieved following radical amputation, phantom pain will frequently be a postoperative issue. A dedicated pain/palliative care team is an invaluable resource for successfully managing perioperative and chronic postoperative pain associated with major amputations.

As noted, a major limitation to our study is the lack of a formal quality of life survey. Only a few published reports have carefully evaluated quality of life outcomes following radical amputations. Merimsky and coworkers looked at quality of life following palliative FQ amputation in 12 patients. They compared preoperative and postoperative Karnofsky performance status in addition to quality of life surveys. They reported improvements in functional status and quality of life in over two-thirds of the patients [11]. Blader et al. [19] reported on 35 patients with major amputations of the upper extremity for malignant tumors. Half of the patients maintained their occupations and reported no major issues with activities of daily living. Refaat et al. conducted a quality of life survey comparing amputations versus limb preservation for sarcoma. Responses included 66 amputations and 342 limb-salvage patients. They reported no significant differences in mobility, independence, employment, anxiety, drug-dependence, psychological stress and disorders, or sexual performance. Seventy-two percent of amputation group was satisfied with their quality of life after surgery compared to 74% of the limbsalvage group [50]. Collectively, these studies underscore the value of radical amputation as a palliative intervention in the appropriate setting.

FQ and HQ amputations are uncommon procedures that require the technical experience of surgical and orthopedic oncologists. Patients with advanced extremity tumors should be referred to a tertiary care center that specializes in the multidisciplinary management of these complex problems. All potential treatment options should be considered prior to proceeding with radical surgery. If amputation is the only viable option, then patients will benefit from preoperative assessment and education by physical and occupational therapists, prosthetitians, psychological counselors, and social workers. We have found that discussions with previous patients who have undergone these procedures can be helpful in allaying a prospective patient’s natural fears and anxiety. Of course, a strong social support system is beneficial in enduring the postoperative recovery. Finally, an experienced rehabilitation team is important in maximizing recovery. Early mobilization is critical in avoiding the negative consequences of immobility. And while the majority of patients will not achieve prosthetic ambulation due to the high level of energy required, all patients should be evaluated by a prosthetitian pre- and postoperatively to provide the potential resources necessary for such a recovery (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Example of a postoperative rehabilitation with prosthesis.

CONCLUSION

FQ and HQ amputations are radical operations indicated for advanced tumors of the extremities when all other treatment options have been exhausted. At experienced centers, major amputations can be performed safely with acceptable morbidity and low mortality rates. Palliation of complex wounds and disabling pain can undoubtedly improve quality of life. While postoperative complications are common, they can be successfully managed in the vast majority of patients. Despite negative margin resections, local and distant recurrence rates are often high and reflect aggressive tumor biology. The most significant impact of these amputations is the palliation of debilitating symptoms. However, prolonged disease-free and postoperative overall survival can be achieved in some patients undergoing these radical procedures.

TABLE III.

Median Postoperative Survival by Therapeutic Intent

| FQ | HQ | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, months (range) | 9.8 (3–56) | 18.7 (1–34) | 10.9 (1–56) |

| Cure | 10.9 (8–56) | — | 10.9 (8–56) |

| Palliation/cure | 6.9 (3–53) | 18.7 (16–34) | 13.2 (3–53) |

| Palliation | 3.4 (3–39) | 4.8 (1–7) | 3.4 (1–39) |

Abbreviations

- FQ

forequarter amputation

- HQ

hindquarter amputation

- DFS

disease-free survival

- OS

postoperative overall survival

- ILI

isolated limb infusion

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

REFERENCES

- 1.Keevil JJ. Ralph Cuming and the interscapulothoracic amputation in 1808. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31B:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby A. The first operation on record for removal of the entire arm, scapula, and three-fourths of the clavicle by Dixie Crosby, Concord, NH. The Medical Record. 1875;10:753–755. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter SR, Eastwood DM, Grimer RJ, et al. Hindquarter amputation for tumours of the musculoskeletal system. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:490–493. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B3.2341454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbas JS, Holyoke ED, Moore R, et al. The surgical treatment and outcome of soft-tissue sarcoma. Arch Surg. 1981;116:765–769. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1981.01380180025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiu MH, Castro EB, Hajdu SI, et al. Surgical treatment of 297 soft tissue sarcomas of the lower extremity. Ann Surg. 1975;182:597–602. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197511000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karakousis CP, Proimakis C, Walsh DL. Primary soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities in adults. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1208–1212. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stojadinovic A, Jaques DP, Leung DH, et al. Amputation for recurrent soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity: Indications and outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:509–518. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apffelstaedt JP, Zhang PJ, Driscoll DL, et al. Various types of hemipelvectomy for soft tissue sarcomas: Complications, survival and prognostic factors. Surg Oncol. 1995;4:217–222. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(10)80038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimas V, Kargel J, Bauer J, et al. Forequarter amputation for malignant tumours of the upper extremity: Case report, techniques and indications. Can J Plast Surg. 2007;15:83–85. doi: 10.1177/229255030701500204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malawer MM, Buch RG, Thompson WE, et al. Major amputations done with palliative intent in the treatment of local bony complications associated with advanced cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1991;47:121–130. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930470212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merimsky O, Kollender Y, Inbar M, et al. Is forequarter amputation justified for palliation of intractable cancer symptoms? Oncology. 2001;60:55–59. doi: 10.1159/000055297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittig JC, Bickels J, Kollender Y, et al. Palliative forequarter amputation for metastatic carcinoma to the shoulder girdle region: Indications, preoperative evaluation, surgical technique, and results. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77:105–113. doi: 10.1002/jso.1079. discussion 114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz RE, Hillebrand G, Peralta EA, et al. Long-term survival after radical operations for cancer treatment-induced sarcomas: How two survivors invite reflection on oncologic treatment concepts. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:244–247. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine EA, Warso MA, McCoy DM, et al. Forequarter amputation for soft tissue tumors. Am Surg. 1994;60:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanley MA, Ehde DM, Jensen M, et al. Chronic pain associated with upper-limb loss. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:742–751. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181b306ec. quiz 752, 779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pack GT, Miller TR. Exarticulation of the innominate bone and corresponding lower extremity (hemipelvectomy) for primary and metastatic cancer. A report of one hundred and one cases with analysis of the end results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey RW, Stevens DB. Radical exarticulation of the extremities for the curative and palliative treatment of malignant neoplasms. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1961;43-A:845–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck NR, Bickel WH. Interinnomino-abdominal amputations; report of 12 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1948;30A:201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blader S, Gunterberg B, Markhede G. Amputation for tumor of the upper arm. Acta Orthop Scand. 1983;54:226–229. doi: 10.3109/17453678308996561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanous N, Didolkar MS, Holyoke ED, et al. Evaluation of forequarter amputation in malignant diseases. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976;142:381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higinbotham NL, Marcove RC, Casson P. Hemipelvectomy: A clinical study of 100 cases with five-year-follow-up on 60 patients. Surgery. 1966;59:706–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis RC, Jr, Bickel WH. Hemipelvectomy for malignant disease. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;165:8–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.02980190010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mussey RD. Palliative forequarter amputation for recurrent breast carcinoma. AMA Arch Surg. 1956;73:154–156. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01280010156020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor GW, Rogers WP., Jr Hindquarter amputation; experience with eighteen cases. N Engl J Med. 1953;249:963–969. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195312102492402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhagia SM, Elek EM, Grimer RJ, et al. Forequarter amputation for high-grade malignant tumours of the shoulder girdle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:924–926. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b6.7770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark MA, Thomas JM. Major amputation for soft-tissue sarcoma. Br J Surg. 2003;90:102–107. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaques DP, Coit DG, Brennan MF. Major amputation for advanced malignant melanoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merimsky O, Kollender Y, Inbar M, et al. Palliative major amputation and quality of life in cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:151–157. doi: 10.3109/02841869709109223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baliski CR, Schachar NS, McKinnon JG, et al. Hemipelvectomy: A changing perspective for a rare procedure. Can J Surg. 2004;47:99–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borman H, Safak T, Ertoy D. Fibrosarcoma following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41:201–204. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199808000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rickelt J, Hoekstra H, van Coevorden F, et al. Forequarter amputation for malignancy. Br J Surg. 2009;96:792–798. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daigeler A, Lehnhardt M, Khadra A, et al. Proximal major limb amputations—A retrospective analysis of 45 oncological cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark MA, Thomas JM. Amputation for soft-tissue sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karakousis CP, Emrich LJ, Driscoll DL. Variants of hemipelvectomy and their complications. Am J Surg. 1989;158:404–408. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apffelstaedt JP, Driscoll DL, Karakousis CP. Partial and complete internal hemipelvectomy: Complications and long-term follow-up. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donati D, Giacomini S, Gozzi E, et al. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lackman RD, Crawford EA, Hosalkar HS, et al. Internal hemipelvectomy for pelvic sarcomas using a T-incision surgical approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2677–2684. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0843-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collin C, Godbold J, Hajdu S, et al. Localized extremity soft tissue sarcoma: An analysis of factors affecting survival. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:601–612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emrich LJ, Ruka W, Driscoll DL, et al. The effect of local recurrence on survival time in adult high-grade soft tissue sarcomas. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markhede G, Angervall L, Stener B. A multivariate analysis of the prognosis after surgical treatment of malignant soft-tissue tumors. Cancer. 1982;49:1721–1733. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820415)49:8<1721::aid-cncr2820490832>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heise HW, Myers MH, Russell WO, et al. Recurrence-free survival time for surgically treated soft tissue sarcoma patients. Multivariate analysis of five prognostic factors. Cancer. 1986;57:172–177. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860101)57:1<172::aid-cncr2820570133>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huth JF, Eilber FR. Patterns of metastatic spread following resection of extremity soft-tissue sarcomas and strategies for treatment. Semin Surg Oncol. 1988;4:20–26. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williard WC, Hajdu SI, Casper ES, et al. Comparison of amputation with limb-sparing operations for adult soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity. Ann Surg. 1992;215:269–275. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199203000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikolajsen L, Jensen TS. Phantom limb pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:107–116. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fainsinger RL, de Gara C, Perez GA. Amputation and the prevention of phantom pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:308–312. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enneking FK, Scarborough MT, Radson EA. Local anesthetic infusion through nerve sheath catheters for analgesia following upper extremity amputation. Clinical report. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:351–356. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(97)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jahangiri M, Jayatunga AP, Bradley JW, et al. Prevention of phantom pain after major lower limb amputation by epidural infusion of diamorphine, clonidine and bupivacaine. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76:324–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikolajsen L, Ilkjaer S, Christensen JH, et al. Randomised trial of epidural bupivacaine and morphine in prevention of stump and phantom pain in lower-limb amputation. Lancet. 1997;350:1353–1357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schug SA, Burrell R, Payne J, et al. Pre-emptive epidural analgesia may prevent phantom limb pain. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Refaat Y, Gunnoe J, Hornicek FJ, et al. Comparison of quality of life after amputation or limb salvage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:298–305. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200204000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Synopsis for Table of Contents.