Abstract

Purpose

To describe daily levels of sitting, moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA), television viewing, and computer use in a representative sample of US adolescents and to make comparisons between sex, race/ethnicity, weight status, and age groups.

Methods

Results are based on 3556 adolescents aged 12-19 years from the 2007-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Participants self-reported demographic variables and their sitting, MVPA, and television viewing (2011-2012 only) and computer use (2011-2012 only) levels. Height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index. Descriptive data were calculated and ANOVA, chi-square, and logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine demographic differences.

Results

On average, 7.5 hours/day were spent sitting, with females sitting more than males across the majority of demographic groups. Furthermore, obese males sat more than non-overweight males. For MVPA, the overall sample participated in a median 34 minutes/day, with females participating in less MVPA than males across all demographic groups. Additionally, non-overweight males participated in more MVPA than obese males, and non-Hispanic white females participated in more MVPA than females in all other race/ethnicity groups. For television viewing and computer use, 38% and 22% of the sample engaged in more than 2 hours/day, respectively, and several race/ethnicity differences were observed.

Conclusions

This study provides the first US population estimates on the levels of sitting and updates population estimates of MVPA, television viewing and computer use in US adolescents. Continued efforts are needed to promote healthy active lifestyles in American adolescents.

Keywords: Sedentary Lifestyle, Television, Computers, Adolescent

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that regular moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) in adolescence is associated with numerous physiological and psychosocial health benefits that are important for chronic disease prevention.1,2 Independent of the beneficial effects of MVPA, a growing body of research indicates that minimizing sedentary behavior or sitting, in particular screen-based sedentary behavior (e.g., television viewing, computer use), during adolescence is also associated with several health benefits.3-5

Recent population estimates for the proportion of American adolescents meeting national physical activity recommendations6 indicates 25% are participating in 60 minutes of MVPA per day.7 However, the most recent population estimates for daily levels of MVPA and sedentary time in US adolescents are several years old. Accelerometry data from the 2003-2006 National Health and Nutrition of Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that 12 to 19 year olds participated in 19 minutes/day of MVPA.2 For sedentary time, an average of 463 and 499 minutes/day were reported for 12 to 15 and 16 to 19 year olds, respectively.8

Belcher and colleagues also examined race/ethnicity and age differences in MVPA and sedentary time for 12 to 19 year olds in the 2003-2006 NHANES.8 For MVPA, on average the 16 to 19 year old group was less active than the 12 to 15 year old group and among 12 to 15 year olds, the non-Hispanic white group was less active than the non-Hispanic black and Mexican American groups. For sedentary time among 12 to 15 year olds, the non-Hispanic white group was less sedentary than the non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American groups, and the non-Hispanic black group was less sedentary than the Mexican-American group.8 In the 2003-2004 NHANES, female adolescents (12 to 19 years old) were reported to be more sedentary than male adolescents.9

Population estimates of minutes/day of screen time have been reported more recently compared to MVPA and sedentary time. Data from the 2009-2010 Health Behavior in School-aged Children study indicates average hours/day of television viewing, video games, and computer use were 2.4, 1.3, and 1.5, respectively, for 11 to 16 year olds.10 However, population estimates of minutes/day sitting in US adolescents have not been reported.

The purpose of this study was to describe daily levels of sitting, MVPA, television viewing, and computer use in a representative sample of US adolescents from the 2007-2012 NHANES and to make comparisons between sex, race/ethnicity, weight status, and age groups.

METHODS

Participants

The study is based on the 2007-2008, 2009-2010, and 2011-2012 cycles of NHANES, which uses a complex multi-stage probability sampling procedure to select a representative sample of the US population from all age groups. NHANES consisted of a home interview and a physical examination and interview conducted in a mobile examination center (MEC). A total of 3,850 adolescents aged 12 to 19 years were eligible for this study (1238 from the 2007-2008 cycle, 1339 from the 2009-2010 cycle, and 1273 from the 2011-2012 cycle). Ethics approval was obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents/guardians if <18 years old.

Sitting

Sitting was assessed by asking participants at the home (aged 16-19 years) or the MEC (aged 12-15 years) interview for the 2007-2008 cycle, “How much time do you usually spend sitting or reclining on a typical day” and in the 2009-2012 cycles, “How much time do you usually spend sitting on a typical day”. In the 2007-2008 cycle, participants were asked to consider time spent sitting or reclining at work, at home, or at school, including at a desk, with friends, traveling in a car, bus or train, reading, playing cards, watching television, or using a computer, but not sleeping. In the 2009-2012 cycles, participants were asked to consider sitting at work, at home, getting to and from places, or with friends, including time spent sitting at a desk, traveling in a car or bus, reading, playing cards, watching television, or using a computer, but not sleeping.

Moderate- to Vigorous-Intensity Physical Activity (MVPA)

MVPA was assessed by asking participants four questions at the home (aged 16-19 years) or the MEC (aged 12-15 years) interview. For vigorous-intensity activity, participants were asked, “In a typical week, on how many days do you do vigorous-intensity sports, fitness or recreation activities?” and “How much time do you spend doing vigorous-intensity sports, fitness or recreational activities on a typical day?”. The responses for both questions were multiplied to calculate minutes/week of vigorous-intensity activities. For moderate-intensity activity participants were asked, “In a typical week, on how many days do you do moderate-intensity sports, fitness or recreational activities?” and “How much time do you spend doing moderate-intensity sports, fitness or recreational activities on a typical day?” The responses for both questions were multiplied to calculate minutes/week of moderate-intensity activities. MVPA was calculated by adding minutes/week of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activities and then dividing by seven to calculate minutes/day of MVPA.

Screen Time (Television and Computer)

Television viewing and computer use were assessed by asking participants at home (aged 16-19 years) or the MEC (aged 12-15 years) interview, “Over the past 30 days, on average how many hours per day did you sit and watch TV or videos?” and “Over the past 30 days, on average how many hours per day did you use a computer or play computer games outside of work or school?” Participants were asked to include PlayStation, Nintendo DS, or other portable video games. For both television and computer questions there were 7 response options ranging from “do not watch TV or videos” or “do not use a computer outside of work or school” to “5 hours or more” Participants were categorized into three groups (≤1 hour/day, >1 to ≤2 hours/day, >3hours/day) based on frequency distributions. . These questions were only asked of participants ≥12 years of age in the 2011-2012 cycle. Therefore, these data were not available for participants in the 2007-2010 cycles for the present study.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

The height and weight of participants were measured at the MEC. Participants were classified according to their age- and sex-specific body mass index (BMI) percentile using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.11 Specifically, weight status for participants were classified as “obese” if the BMI was ≥95th percentile, “overweight” if the BMI was ≥85th and <95th percentile, and “non-overweight” if the BMI was <85th percentile.

Demographics

Participants reported their age, sex, and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican-American, and other) at the home interview. The other category included other Hispanic (not Mexican-American) and other race/ethnicities.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were completed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and accounted for the complex design and sample weights of NHANES. The 2-year MEC sample weights were adjusted for the combined data sets prior to analyses following the National Centre for Health Statistics recommendations.12 MVPA was highly positively skewed and required log-transformation to meet the assumption of normality in the ANOVA models. Descriptive data for sitting, MVPA, television, and computer were calculated for the total sample and for sex, race/ethnicity, and weight-status stratified models. Descriptive data for sitting and MVPA were also calculated by age groups (12-13, 14-15, 16-17, 18-19 years). Descriptive results are expressed as mean (standard error) minutes/day for sitting, median (inter-quartile range) minutes/day for MVPA, and proportions for television and computer groups. ANOVAs were used to examine differences in minutes/day of sitting and log MVPA between sex, race/ethnicity, weight status, and age groups. If a significant race/ethnicity, weight status, or age effect was observed in the ANOVA model, group contrasts were conducted. Chi-square analysis was used to examine differences in proportion of television viewing and computer use between sex, race/ethnicity, and weight status groups. If a significant chi-square was observed for race/ethnicity or weight status, a multinomial logistic regression was conducted with ≤1 hour/day of television or computer, non-Hispanic white, and non-overweight as the reference groups. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for main effects and at a stricter P<0.01 for contrasts to minimize type 1 error, given the number of tests.

RESULTS

Of the 3850 eligible participants in the 2007-2012 cycles, 3556 had complete data for sitting, MVPA, BMI, and demographic variables. However, 3 participants were excluded as outliers because they reported greater than 1420 minutes/day of MVPA, leaving a total sample of 3553. Of the 1273 eligible participants in the 2011-2012 cycle, 1178 participants had complete data for television viewing, computer use, BMI, and demographic variables. For the 2007-2012 cycles, weighted to the population, median age was 15.5 years, approximately half of the sample was male, 58% were non-Hispanic White, 15% were non-Hispanic Black, and 13% were Mexican-American. For weight status, 15% of the sample was classified as overweight and 20% were classified as obese.

Average daily minutes spent sitting in the total sample and sex, race/ethnicity, and weight status stratified groups are presented in Table 1. In the total sample, adolescents spent an average of 7.5 hours/day sitting, with females spending on average 39 more minutes/day sitting compared to males. In the stratified analyses, on average females also spent significantly more minutes/day sitting compared to males in the non-overweight status group (49 more minutes/day) and in each race/ethnicity group (36 to 46 more minutes/day), but no sex differences were observed in the race/ethnicity group classified as other. There were no significant differences in minutes/day spent sitting between race/ethnicity groups. However, for males there was a significant difference between weight status groups. Specifically, on average the obese group spent 43 more minutes/day sitting compared to the non-overweight group. For males and females, the 18 to 19 year old age group spent fewer minutes/day sitting than any other group (Figure 1). For males, the 16 to 17 year old age group also spent fewer minutes/day sitting than the 12 to 13 and 14 to 15 year old age groups.

Table 1.

Mean (SE) of self-reported minutes/day spent sitting, stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, and weight status groups (n = 3553)

| Race/ethnicity | Weight Status (CDC) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total† | Non-Hispanic White† | Non-Hispanic Black† | Mexican-American† | Other | Obese | Overweight | Non-overweight† | |

| Total | 448.1 (6.5) | 449.5 (9.3) | 443.4 (8.6) | 439.1 (9.4) | 455.4 (11.1) | 471.2 (10.3) | 443.1 (12.4) | 442.2 (7.2) |

| Males | 429.0 (7.3) | 426.8 (9.9) | 424.9 (12.6) | 421.7 (13.4) | 449.7 (15.5) | 460.8 (12.6)a | 433.3 (16.5) | 418.0 (8.3)a |

| Females | 468.2 (7.9) | 473.4 (11.5) | 462.6 (11.1) | 458.4 (9.9) | 461.4 (11.7) | 483.3 (14.1) | 453.3 (16.2) | 467.4 (9.1) |

Significant sex differences in sitting time (P<0.05)

Significant difference in sitting time between the obese and non-overweight groups within the male sample (P<0.01)

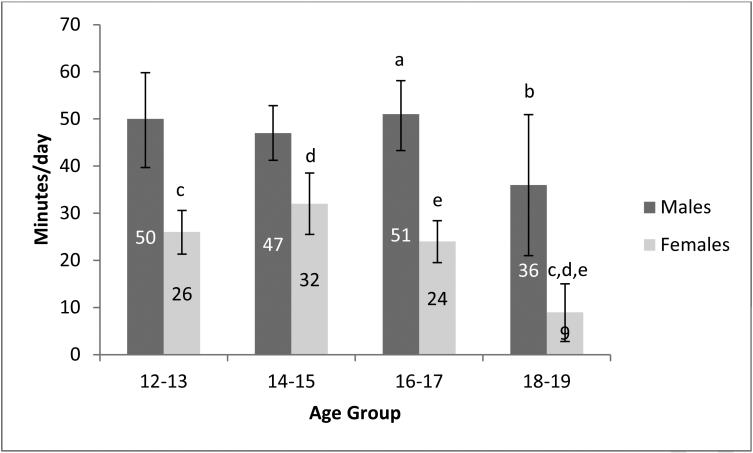

Figure 1.

Mean (95% CI) Sitting time among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents stratified by age and sex groups. a,b Significant differences in sitting time between the 12-13 year age group and the 16-17 year and 18-19 year age groups within the male sample (P<0.01). c,d Significant differences in sitting time between the 14-15 year age group and the 16-17 year and 18-19 year age groups within the male sample (P<0.01). e Significant differences in sitting time between the 16-17 year and 18-19 year age groups within the male sample (P<0.01). f,g,h Significant differences in sitting time between the 18-19 year age group and all other age groups (P<0.01).

Median minutes/day in MVPA for the total sample and sex, race/ethnicity, and weight status stratified groups are presented in Table 2. In the total sample, adolescents spent a median 34 minutes/day in MVPA, with males spending 22 more median minutes/day in MVPA compared to females. In the stratified analyses, on average males spent significantly more minutes/day in MVPA compared to females across all race/ethnicity (18 to 35 more median minutes/day) and weight status (21 to 30 more median minutes/day) groups. In the total sample and female sample, on average the Non-Hispanic White group spent significantly more minutes/day in MVPA compared to all other race/ethnicity groups (10 to 14 more median minutes/day for the total sample and 10 more median minutes/day for the female sample). Additionally, in the total sample and male sample, on average the obese group spent significantly fewer minutes/day in MVPA compared to the non-overweight group (12 fewer median minutes/day for the total sample and 13 fewer median minutes/day for the male sample). For females, the 18 to 19 year old age group spent fewer minutes/day in MVPA compared to all other age groups (Figure 2). For males, the 18 to 19 year old age group spent fewer minutes/day in MVPA compared to the 16 to 17 year old age group.

Table 2.

Median (IQR) of self-reported minutes/day spent in MVPA, stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, and weight status groups (n = 3553)

| Race/ethnicity | Weight Status (CDC) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total† | Non-Hispanic White† | Non-Hispanic Black† | Mexican-American† | Other† | Obese† | Overweight† | Non-overweight† | |

| Total | 34.0 (8.1, 78.9) | 39.3 (12.7, 80.4)a,b,c | 29.7 (0, 68.5)a | 25.4 (2.2, 62.9)b | 25.4 (0, 64.8)c | 24.8 (3.9, 67.4)d | 32.3 (8.1, 82.2) | 37.1 (8.5, 76.3)d |

| Males | 46.8 (16.6, 85.3) | 51.1 (17.0, 89.3) | 50.7 (12.3, 85.0) | 33.7 (12.1, 76.3) | 41.5 (11.7, 79.3) | 37.6 (8.2, 80.1)d | 50.6 (16.8, 102.0) | 50.7 (16.9, 85.3)d |

| Females | 25.1 (0, 53.3) | 25.7 (6.9, 64.1)a,b,c | 15.8 (0, 48.9)a | 16.1 (0, 42.9)b | 16.1 (0, 41.0)c | 16.9 (0, 40.6) | 20.8 (0, 50.7) | 25.5 (0.9, 59.3) |

Significant sex differences in log MVPA (P<0.05)

Significant differences in log MVPA between the non-Hispanic white group and all other race/ethnicity groups within the total sample and female sample (P<0.05)

Significant differences in log MVPA between the non-Hispanic white group and all other race/ethnicity groups within the total sample and female sample (P<0.05)

Significant differences in log MVPA between the non-Hispanic white group and all other race/ethnicity groups within the total sample and female sample (P<0.05)

Significant differences in log MVPA between the obese and non-overweight groups within the total sample and male sample (P<0.01)

Figure 2.

Median (95% CI) MVPA among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents stratified by age and sex groups. a,bSignificant difference in MVPA between the 16-17 and 18-19 year age-groups within the male sample (P<0.01). c,d,e Significant differences in MVPA between the 18-19 year age group and all other age groups within the female sample (P<0.01).

Proportion of television viewing and computer use for the total sample and sex, race/ethnicity, and weight status stratified groups are presented in Table 3. In the total sample, 36%, 26%, and 38% were in the ≤1 hour/day, >1 to ≤2 hours/day, and ≥3 hours/day television groups, respectively. For computer use, 61%, 17%, and 22% were in the ≤1 hour/day, >1 to ≤2 hours/day, and ≥3 hours/day, respectively. No significant differences in frequencies were observed between sex or weight-status groups for television or computer. However, differences in frequencies between race/ethnicity groups were observed for television and computer. For television, with ≤1 hour/day as the reference, the non-Hispanic black group was more likely to be in the ≥3 hours/day television group compared to the non-Hispanic white group. For computer, with ≤1 hour/day as the reference, the non-Hispanic black group was more likely and the Mexican-American group was less likely to be in the >1 to ≤2 hours/day and ≥3 hours/day groups compared to the non-Hispanic white group. The race/ethnicity group classified as other was also more likely to be in the ≥3 hours/day group compared to the non-Hispanic white group.

Table 3.

Daily television viewing and computer use categories (%) in the 2010-2011 subsample, stratified by sex, race/ethnicity and weight status groups (n = 1178)

| Sex | Race/ethnicity | Weight Status (CDC) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Mexican-American | Other | Obese | Overweight | Non-overweight | |

| Television | ||||||||||

| ≤1 hour/day | 36.2 | 35.0 | 37.4 | 38.9 | 27.8 | 30.3 | 39.9 | 31.0 | 37.4 | 37.7 |

| >1 to ≤2 hours/day | 26.3 | 26.9 | 25.7 | 25.9 | 25.8 | 29.9 | 25.2 | 24.8 | 25.7 | 27.0 |

| ≥3 hours/day | 37.5 | 38.0 | 36.9 | 35.2a | 46.3a | 39.8 | 34.9 | 44.2 | 36.9 | 35.3 |

| Computer | ||||||||||

| ≤1 hour/day | 60.6 | 60.0 | 62.3 | 62.6 | 48.8 | 74.3 | 53.0 | 58.6 | 55.6 | 62.5 |

| >1 to ≤2 hours/day | 17.4 | 19.8 | 15.2 | 16.9b,c | 22.6b | 13.2c | 17.9 | 15.8 | 24.9 | 16.1 |

| ≥3 hours/day | 22.0 | 21.4 | 22.5 | 20.5d,e,f | 28.6d | 12.5e | 29.1f | 25.8 | 19.5 | 21.3 |

Significant likelihood of having higher (≤1 hour/day vs. ≥3 hours/day) television viewing in comparison to the non-Hispanic white reference group (P<0.01)

Significant likelihood of having lower/higher (≤1 hour/day vs. >1 to ≤2 hours/day) computer use in comparison to the non-Hispanic white reference group (P<0.01)

Significant likelihood of having lower/higher (≤1 hour/day vs. >1 to ≤2 hours/day) computer use in comparison to the non-Hispanic white reference group (P<0.01)

Significant likelihood of having lower/higher (≤1 hour/day vs. ≥3 hours/day) computer use in comparison to the non-Hispanic white reference group (P<0.01)

Significant likelihood of having lower/higher (≤1 hour/day vs. ≥3 hours/day) computer use in comparison to the non-Hispanic white reference group (P<0.01)

Significant likelihood of having lower/higher (≤1 hour/day vs. ≥3 hours/day) computer use in comparison to the non-Hispanic white reference group (P<0.01)

DISCUSSION

This study described the daily levels of self-reported sitting, MVPA, television viewing and computer use in a recent representative sample of US adolescents. Adolescents spent on average 7.5 hours/day sitting, with females sitting more than males across the majority of race/ethnicity, weight status, and age groups. Furthermore, obese males sat more than non-overweight males. For MVPA, the overall sample participated in a median 34 minutes/day, with females participating in less MVPA than males across all race/ethnicity, weight status, and age groups. Additionally, non-overweight males participated in more MVPA than obese males, and non-Hispanic white females participated in more MVPA than females in all other race/ethnicity groups. For television viewing and computer use, 38% and 22% of the sample engaged in more than 2 hours/day, respectively, and several race/ethnicity differences were observed.

To our knowledge, this is the first population estimate of minutes/day of sitting among US adolescents. A recent study based on the 2009-2010 NHANES reported that US adults spend an average of 4.7 hours/day sitting13 or approximately 3 hours/day less than what was observed for adolescents. Self-reported sitting time declined with age in the current study, with 18 to 19 year old males and females spending 5.6 and 6.2 hours/day, respectively. The higher average levels of sitting observed for 12 to 17 years olds may be explained by practices and policies within the school setting that promote sitting. Furthermore, future research is needed to determine whether a social bias towards sitting develops as children get older.

While a population estimate of minutes/day sitting has not been previously reported for adolescents, sedentary time based on accelerometer data has been. Belcher and colleagues reported that adolescents aged 12 to 15 and 16 to 19 year olds in the 2003-2006 NHANES spent 7.7 and 8.3 hours/day sedentary, respectively. Similarly, based on the 2003-2004 NHANES, Matthews and colleagues reported that adolescents aged 12 to 15 and 16 to 19 years spent 7.5 and 8 hours/day sedentary, respectively. While these studies did not observe an age decline in sedentary time for adolescents, the hours/day reported for sedentary time are similar with what was reported for sitting in the present study. Similar accelerometer data reduction procedures were used in the Belcher and Matthews studies.8,9 It has been shown that different data reduction procedures for accelerometers (i.e., cut-points, wear time definitions) can impact the estimates of sedentary time.14

Previous population estimates of MVPA have also been reported from the 2003-2006 NHANES accelerometer data. These data show that adolescents aged 12 to 19 years participated in 19 median minutes/day of MVPA.2 This is approximately half the median minutes/day reported in the present study. Systematic review evidence indicates indirect measures of physical activity are typically higher than direct measures.15 This is likely due to biases associated with self-report measures such as information bias and social desirability bias.15 Also accelerometers do not capture all activities, such as swimming or cycling. Consequently, comparing physical activity levels across studies can be challenging when different measures are used. The population estimate of 33 median minutes/day of MVPA in the current study is still well below national recommendations of 60 minutes/day of MVPA for this age group.6 This is consistent with a recent report based on self-report data from the combined 2012 NHANES and the NHANES National Youth Survey that reported only 25% of American youth meet national guidelines.7

Regardless of whether direct or indirect measures of MVPA are used, the findings that females are less active than males is consistent.16 In the present study, this gender difference was consistent across all other sub-groups. Females also had higher minutes/day of sitting across most subgroups, which is consistent with findings on sedentary time from the 2003-2004 NHANES.9 Therefore, adolescent females may be an important target group for interventions and initiatives aiming to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior. A study in Australian adolescent females indicates the school day may be the most optimal time to intervene.17 Among adolescent females, those aged 18 to 19 years had the lowest levels of MVPA at 9 median minutes/day. This is consistent with previous studies that have reported a decline in physical activity, particularly for females during the transition from high school to work or college.18,19 Furthermore, females in the non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, and other race/ethnicity groups participated in less MVPA than the non-Hispanic white group. Interestingly, this is opposite to the findings from NHANES 2005-2006, where average levels of MVPA were lower for the 12 to 15 year old non-Hispanic white group. It is unclear if the physical activity questions were interpreted differently between race/ethnicity groups. Research in adults indicates there is race/ethnicity variation in how participants define physical activity.20

The proportion of adolescents in the present study exceeding two hours/day of television viewing is similar to the 35% reported for 12 to 15 years olds in the 2001-2006 NHANES.21 However, double the proportion of adolescents in the current study exceeded two hours/day of computer use compared to the 2001-2006 NHANES.21 An increase in computer use from 1999 to 2009 was also observed in a nationally representative sample of 8 to18 year olds in a report by the Kaiser Foundation.22 It has been suggested that the growth of online media and expansion of high speed internet may explain this trend.22

Similar to MVPA there were also race/ethnicity differences in proportion of television viewing and computer use. In line with 2001-2006 NHANES cycles, the non-Hispanic black group were more likely to be high (≥ 3 hours/day) television viewers and computer users compared to the non-Hispanic white group.21 Therefore, non-Hispanic blacks may be an important target group to consider for future screen time interventions and initiatives. In contrast to sitting and MVPA, no sex differences were observed in the proportion of television viewing and computer use. This is consistent with previous cycles of the NHANES when specifically looking at 12 to 15 year olds.21 However, the present findings are inconsistent with another nationally representative sample of US adolescents (11 to 16 years old) from the Health Behavior in School-aged Children study, where males were found to engage in more television viewing than females and females were found to engage in more computer user than males.10

While consistent associations have previously been reported between screen time, in particular television viewing, and adiposity in children and adolescents,5 the proportion of television viewing and computer use did not differ based on weight status in the present study. Interestingly, obese males had higher levels of daily sitting compared to normal weight males. The opposite association was observed with MVPA. The majority of work examining total sedentary time and health outcomes in adolescents has used accelerometers, which are not sensitive enough to differentiate between sitting and standing.23 Therefore, future research using validated sitting questions or an objective measure of sitting such as an inclinometer is needed to examine the associations of sitting with health outcomes and whether these associations differ between demographic groups.

Strengths of this study include the large nationally representative sample of US adolescents and the first population estimates of sitting for this age group. A limitation of the study is the self-reported measures of sitting, MVPA, and screen time, which may have resulted in information bias. However, these more recent data using self-report measures in the present study allowed for updated population estimates to be reported for US adolescents.

CONCLUSION

This study provides the first population estimates on the levels of sitting and updates population estimates on the levels of MVPA, television viewing, and computer use in US adolescents. Overall, adolescents are spending a large portion of waking hours sitting and are participating in minimal MVPA. This is particularly true for adolescent females. Television viewing and computer use continue to be dominant types of sedentary behavior, with non-Hispanic black participation the highest. Continued efforts are needed to promote healthy active lifestyles in American adolescents.

Acknowledgements

AES is supported in part, by 1 U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. PTM is supported, in part, by the Marie Edana Corcoran Endowed Chair in Pediatric Obesity and Diabetes.

Abbreviations

- MVPA

moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- BMI

Body Mass Index

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. There was no study sponsor. VC wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

Adolescents spend the majority of their waking hours sitting and participate in minimal MVPA. Television viewing and computer use continue to be dominant types of sedentary behavior. This study presents the first population estimates of sitting and updates estimates on MVPA, television viewing and computer use among US adolescents.

References

- 1.Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2010;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson V, Ridgers ND, Howard BJ, Winkler EA, Healy GN, Owen N, Dunstan DW, Salmon J. Light-intensity physical activity and cardiometabolic biomarkers in US adolescents. PloS one. 2013;8:e71417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson V, Janssen I. Volume, patterns, and types of sedentary behavior and cardio-metabolic health in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2011;11:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark AE, Janssen I. Relationship between screen time and metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Journal of public health. 2008;30:153–60. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, Goldfield G, Connor Gorber S. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2011;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services US Department of Agriculture: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2005 Mar; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhouri TH, Hughes JP, Burt VL, Song M, Fulton JE, Ogden CL. Physical activity in u.s. Youth aged 12-15 years, 2012. NCHS data brief. 2014:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belcher BR, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Emken BA, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D. Physical activity in US youth: effect of race/ethnicity, age, gender, and weight status. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2010;42:2211–21. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e1fba9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, Troiano RP. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. American journal of epidemiology. 2008;167:875–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iannotti RJ, Wang J. Trends in physical activity, sedentary behavior, diet, and BMI among US adolescents, 2001-2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132:606–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) A SAS program for the CDC growth charts. 2011 Available at: www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm.

- 12.National Centre for Health Statistics Specifying weighting parameters. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/nhanes/SurveyDesign/Weighting/intro.htm.

- 13.Harrington DM, Barreira TV, Staiano AE, Katzmarzyk PT. The descriptive epidemiology of sitting among US adults, NHANES 2009/2010. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winkler EA, Gardiner PA, Clark BK, Matthews CE, Owen N, Healy GN. Identifying sedentary time using automated estimates of accelerometer wear time. British journal of sports medicine. 2012;46:436–42. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamo KB, Prince SA, Tricco AC, Connor-Gorber S, Tremblay M. A comparison of indirect versus direct measures for assessing physical activity in the pediatric population: a systematic review. International journal of pediatric obesity : IJPO : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2009;4:2–27. doi: 10.1080/17477160802315010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2000;32:963–75. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carson V, Cliff DP, Janssen X, Okely AD. Longitudinal levels and bouts of sedentary time among adolescent girls. BMC pediatrics. 2013;13:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell S, Lee C. Emerging adulthood and patterns of physical activity among young Australian women. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2005;12:227–35. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horn DB, O'Neill JR, Pfeiffer KA, Dowda M, Pate RR. Predictors of physical activity in the transition after high school among young women. Journal of physical activity & health. 2008;5:275–85. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warnecke RB, Johnson TP, Chavez N, Sudman S, O'Rourke DP, Lacey L, Horm J. Improving question wording in surveys of culturally diverse populations. Annals of epidemiology. 1997;7:334–42. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisson SB, Church TS, Martin CK, Tudor-Locke C, Smith SR, Bouchard C, Earnest CP, Rankinen T, Newton RL, Katzmarzyk PT. Profiles of sedentary behavior in children and adolescents: the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2006. International journal of pediatric obesity : IJPO : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2009;4:353–9. doi: 10.3109/17477160902934777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF. Generation M2 Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year- olds: A Kaiser Family Foundation study. 2011 http://www.kff.org/entmedia/mh012010pkg.cfm.

- 23.Chastin SF, Granat MH. Methods for objective measure, quantification and analysis of sedentary behaviour and inactivity. Gait & posture. 2010;31:82–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]