Abstract

We assessed alcohol consumption and depression in 234 American Indian/Alaska Native women (aged 18–45 years) in Southern California. Women were randomized to intervention or assessment alone and followed for 6 months (2011–2013). Depression was associated with risk factors for alcohol-exposed pregnancy (AEP). Both treatment groups reduced drinking (P < .001). Depressed, but not nondepressed, women reduced drinking in response to SBIRT above the reduction in response to assessment alone. Screening for depression may assist in allocating women to specific AEP prevention interventions.

Women who consume alcohol and do not practice effective contraception are at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy (AEP). AEPs can lead to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, the leading known cause of developmental disabilities.1–3 Prepregnancy drinking, particularly heavy episodic or binge drinking, is a robust predictor of AEP.4 Depression has been linked to problem alcohol consumption in women5–7 and appears to predate8,9 and perhaps predict10 alcohol problems. Among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) women, studies have linked depression to problem drinking.11–13 However, risk factors for an AEP and interventions to reduce risk for AEP have not been well studied in AI/AN women.14 This is further complicated by variability among AI/AN populations in the prevalence of alcohol consumption11,15–20 and depression.13,21–23

One approach to prevention of AEPs is screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT).24,25 We previously tested the effectiveness of an SBIRT intervention in AI/AN women and found that whether women received an assessment followed by the SBIRT intervention or assessment alone, they reported a significant reduction in alcohol use. We examined depression as a predictor of vulnerability to having an AEP and explored whether depressed AI/AN women respond differently than nondepressed women to an SBIRT intervention.

METHODS

Between 2011 and 2012, we recruited nonpregnant AI/AN women aged 18 to 45 years from Southern California health clinics into an intervention trial. Methods, measures, and the intervention itself are described in detail elsewhere.26 All participants were assessed for quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption and other health behaviors. We used the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire27 to measure depression and functionality. Women were then randomized into the intervention or the control group. Intervention group women completed a Web-based survey providing personalized feedback. All participants were followed up by telephone at 1, 3, and 6 months. Including follow-up, the study spanned 2011 to 2013.

To compare groups, we used repeated-measures analysis of variance and mixed-model methods including interaction terms. Separate analyses were stratified on depression. Analyses were performed using multiple imputation methods in PASW Statistics version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). We used a 2-sided P < .05 to judge significance.

RESULTS

We recruited 234 nonpregnant AI/AN women from Southern California health clinics, both reservation based and urban; 15 (6.4%) were lost to follow-up. Using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, we identified 84 women (36%) as depressed. Riskier alcohol consumption and contraceptive practices were associated with depression (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Characterization of Population Sample by Depression Status: Southern California, 2011–2013

| Not Depressed |

Depressed |

||||

| Variable | Mean ±SE or % | No. | Mean ±SE or % | No. | Pa |

| Age, y | 28.3 ±0.6 | 147 | 29.3 ±0.8 | 83 | .358 |

| Has had a child | 59.6 | 146 | 73.5 | 83 | .034 |

| No. of pregnancies | 1.92 ±0.19 | 142 | 2.11 ±0.21 | 82 | .522 |

| No. of children | 1.42 ±0.13 | 146 | 1.66 ±0.16 | 83 | .241 |

| Wants more children | 61.4 | 140 | 58.2 | 79 | .642 |

| Employed | 44.4 | 144 | 36.3 | 80 | .233 |

| Religious | 140 | 79 | .85 | ||

| Not at all | 12.9 | 13.9 | |||

| Somewhat | 74.3 | 70.9 | |||

| Very | 12.9 | 15.2 | |||

| Cohabitating | 46.2 | 145 | 35.4 | 82 | .112 |

| Birth control use | |||||

| Use birth controlb | 63.9 | 147 | 51.8 | 84 | .072 |

| Abstinent | 10.0 | 7.6 | |||

| No birth control | 25.6 | 42.5 | |||

| Using birth control correctly | 78.3 | 55.0 | < .001 | ||

| Birth control effectiveness | 93 | 42 | .069 | ||

| High | 19.4 | 23.8 | |||

| Medium high | 45.1 | 45.2 | |||

| Medium low | 35.5 | 28.6 | |||

| Low | 0 | 2.4 | |||

| Smoker | 29.3 | 147 | 34.9 | 83 | .372 |

| Drug use | |||||

| Taking illegal drugs | 9.0 | 145 | 20.3 | 79 | .016 |

| Taking prescription drugs | 32.9 | 146 | 57.5 | 80 | < .001 |

| Taking depression medication | 5.5 | 146 | 16.5 | 79 | .007 |

| Taking anxiety medication | 5.5 | 145 | 8.9 | 79 | .332 |

| Functionality impaired | 1.8 | 112 | 16.7 | 83 | < .001 |

| Knowledge questions correct | 67 | 37 | |||

| Pregnancy related | 95.0 ±1.3 | 92.5 ±1.8 | .246 | ||

| Women’s health related | 35.1 ±3.5 | 33.3 ±5.6 | .784 | ||

| Total | 84.1 ±1.2 | 81.6 ±1.8 | .232 | ||

| Heard of FASD/FAS | 77.1 | 140 | 71.6 | 81 | .359 |

| Knows someone affected by FASD/FAS | 34.1 | 132 | 36.8 | 76 | .689 |

| Alcohol consumption variables | |||||

| Total sample | |||||

| Drinks/wk | 2.93 ±0.39 | 136 | 6.72 ±1.41 | 78 | .002 |

| Drinks/occasion | 2.38 ±0.33 | 138 | 2.57 ±0.47 | 79 | .738 |

| Binge episodes/2 wk | 0.94 ±0.14 | 136 | 2.20 ±0.58 | 79 | .008 |

| Age at first drink | 15.5 ±0.3 | 138 | 14.5 ±0.45 | 79 | .136 |

| Family dependency risk | 10.1 ±1.1 | 64 | 19.4 ±4.7 | 33 | .014 |

| T-ACE | 1.92 ±0.17 | 64 | 2.35 ±0.27 | 33 | .157 |

| T-ACE severity | 10.3 ±1.3 | 65 | 14.1 ±3.2 | 34 | .195 |

| Perception of other women's drinks/wk | 6.61 ±0.71 | 138 | 9.20 ±1.36 | 72 | .063 |

| Perception of other women's drinks/occasion | 3.41 ±0.30 | 137 | 3.33 ±0.30 | 76 | .862 |

| Current drinkers | |||||

| Drinks/wk | 5.18 ±0.56 | 77 | 13.45 ±2.39 | 39 | < .001 |

| Drinks/occasion | 4.16 ±0.48 | 79 | 5.07 ±0.75 | 40 | .292 |

| Binge episodes/2 wk | 1.58 ±0.20 | 81 | 4.35 ±1.03 | 40 | .001 |

| Age at first drink | 15.4 ±0.3 | 81 | 13.8 ±0.5 | 41 | .007 |

| Family dependency risk | 9.46 ±1.24 | 39 | 22.6 ±6.8 | 16 | .008 |

| T-ACE | 1.92 ±0.20 | 39 | 3.14 ±0.36 | 14 | .003 |

| T-ACE severity | 8.82 ±0.74 | 39 | 19.7 ±6.3 | 14 | .008 |

| Perception of other women's drinks/wk | 6.22 ±0.61 | 78 | 13.6 ±2.3 | 35 | < .001 |

| Perception of other women's drinks/occasion | 3.49 ±0.28 | 76 | 4.39 ±0.48 | 37 | .088 |

Note. FAS = fetal alcohol syndrome; FASD = fetal alcohol spectrum disorders; T-ACE = an alcohol screening questionnaire with questions on tolerance, annoyed, cut down, and eye-opener.

Comparison between depressed and not depressed women using χ2 test or analysis of variance.

Includes abstinence.

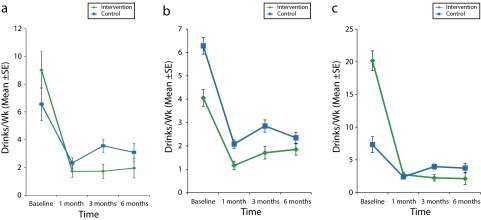

We found a statistically significant time effect (P < .001) but no intervention effect (treatment × time; P = .127) for change in number of drinks per week (Figure 1). However, we found significant interactions between depression and time (P < .001), depression and intervention (P = .021), and among depression, intervention, and time (P < .001).

FIGURE 1—

Estimated marginal mean number of drinks consumed per week over time and by treatment group for (a) all women, (b) nondepressed women, and (c) depressed women: Southern California, 2011–2013.

Note. Groups were compared with repeated-measures analysis of variance with imputed data (n = 123; control group, n = 67; intervention group, n = 56). For the total sample and the not depressed group, time effect P < .001; intervention effect, not significant (P = .127 and .365). For the depressed group, time effect P < .001; intervention effect P < .001. Whiskers indicate standard errors.

When the results were stratified by depression, we found a significant treatment × time effect only among depressed women (P < .001). Among participants in the intervention group, depressed women decreased risky behavior to a greater extent than nondepressed women (P < .001; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this sample of AI/AN women, 36% reported depression. This percentage far exceeds the 14% rate reported in a national study in 2006 using the same screening tool28 and may underestimate the true prevalence because of the limited (61%–88%) sensitivity of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.29,30 Depressed women in our sample reported more drinks per week and more binge episodes than their nondepressed counterparts. Furthermore, depression was linked with poor contraception practices. Inconsistent use of contraception among drinking women31 increases vulnerability to an AEP. Depression was associated with risk factors for vulnerability to an AEP and modified the response to an SBIRT intervention.

The higher level of drinking reported at baseline by depressed participants provided greater opportunity for reduction but did not account for our results. When the analysis was stratified by magnitude of consumption, we found no effect of the intervention above that of assessment alone. In some studies, greater readiness to change has been associated with greater severity of alcohol misuse.32

Evidence has shown that depression may encourage self-awareness33 and a more realistic understanding of personal risk,34 which may contribute to readiness for change. Depression may also motivate problem solving.35,36 Among depressed women, our SBIRT intervention with personalized feedback may have supported the change inspired by assessment. Screening for depression may be particularly important in AEP prevention because onset and prevalence of depression in women37,38 peak during childbearing years. Among some AI/AN populations, women may be at increased risk for depression as a result of living conditions,39–47 historical trauma, loss of culture, discrimination, and conflicts between traditional and modern culture.48–51

Limitations of this study include that data were self-reported and responses may have been influenced by social acceptability. However, we took extensive measures to ensure confidentiality and respect cultural etiquette. The study was carried out by trusted community members trained as research assistants.

These findings suggest that depressed AI/AN women are at increased risk of an AEP and may benefit from more personalized interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM087518) and the Indian Health Service (U26IHS300292/01).

We express our appreciation to the American Indian/Alaska Native women, Southern California Tribal Health Clinic staff, and project consultants for their valuable input and participation and to our wonderful, insightful, patient, and hard-working research assistants, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Human Participant Protection

This protocol was approved by the Southern California Tribal Health Clinic; University of California, San Diego; and San Diego State University institutional review boards. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health to further protect the confidentiality of participants. All research staff completed human research participant protection training. All participants provided informed consent.

References

- 1.Jones KL, Smith DW. Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet. 1973;302(7836):999–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streissguth A. Offspring effects of prenatal alcohol exposure from birth to 25 years: the Seattle Prospective Longitudinal Study. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2007;14(2):81–101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Tenth Special Report to the US Congress on Alcohol and Health: Highlights From Current Research. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethen MK, Ramadhani TA, Scheuerle AE et al. Alcohol consumption by women before and during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(2):274–285. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai J, Floyd RL, O’Connor MJ, Velasquez MM. Alcohol use and serious psychological distress among women of childbearing age. Addict Behav. 2009;34(2):146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker T, Maviglia MA, Lewis PT, Phillip Gossage J, May PA. Psychological distress among Plains Indian mothers with children referred to screening for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR. The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49(3):219–224. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade T, McEvoy PM, Chapman C, Grove R, Teesson M. Onset and temporal sequencing of lifetime anxiety, mood and substance use disorders in the general population. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(1):45–53. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo PH, Gardner CO, Kendler KS, Prescott CA. The temporal relationship of the onsets of alcohol dependence and major depression: using a genetically informative study design. Psychol Med. 2006;36(8):1153–1162. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connell JM, Novins DK, Beals J, Spicer P AI-SUPERPFP Team. Disparities in patterns of alcohol use among reservation-based and geographically dispersed American Indian populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(1):107–116. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153789.59228.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunitz SJ. Life course observations of alcohol use among Navajo Indians: natural history or careers? Med Anthropol Q. 2006;20(3):279–296. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillard DA, Smith JJ, Ferucci ED, Lanier AP. Depression prevalence and associated factors among Alaska Native people: the Alaska Education and Research Toward Health (EARTH) study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):1088–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May PA, Phillip Gossage J. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: not as simple as it might seem. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(1):15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spicer P, Beals J, Croy CD et al. The prevalence of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence in two American Indian populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(11):1785–1797. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000095864.45755.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May PA, Gossage JP. New data on the epidemiology of adult drinking and substance use among American Indians of the northern states: male and female data on prevalence, patterns, and consequences. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2001;10(2):1–26. doi: 10.5820/aian.1002.2001.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May PA. Fetal alcohol effects among North American Indians: evidence and implications for society. Alcohol Health Res World. 1991;15(3):239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 18.May PA, Hymbaugh KJ, Aase JM, Samet JM. Epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome among American Indians of the Southwest. Soc Biol. 1983;30(4):374–387. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1983.9988551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beals J, Spicer P, Mitchell CM et al. Racial disparities in alcohol use: comparison of 2 American Indian reservation populations with national data. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1683–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beals J, Belcourt-Dittloff A, Freedenthal S et al. Reflections on a proposed theory of reservation-dwelling American Indian alcohol use: comment on Spillane and Smith (2007) Psychol Bull. 2009;135(2):339–343. doi: 10.1037/a0014819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duran B, Sanders M, Skipper B et al. Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders among Native American women in primary care. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):71–77. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR et al. Prevalence of major depressive episode in two American Indian reservation populations: unexpected findings with a structured interview. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1713–1722. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keough VA, Jennrich JA. Including a screening and brief alcohol intervention program in the care of the obstetric patient. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(6):715–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montag AC, Brodine SK, Alcaraz JE et al. Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancy among an American Indian/Alaska Native population: effect of a screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment intervention. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(1):126–135. doi: 10.1111/acer.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farr SL, Bitsko RH, Hayes DK, Dietz PM. Mental health and access to services among US women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):542. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.007. e1–542.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berenson AB, Breitkopf CR, Wu ZH. Reproductive correlates of depressive symptoms among low-income minority women. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(6):1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Saitz R et al. Readiness to change in primary care patients who screened positive for alcohol misuse. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(3):213–220. doi: 10.1370/afm.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J. Self-regulatory perseveration and the depressive self-focusing style: a self-awareness theory of reactive depression. Psychol Bull. 1987;102(1):122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser? J Exp Psychol Gen. 1979;108(4):441. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.108.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: a control-process view. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(1):19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews PW, Thomson JA., Jr The bright side of being blue: depression as an adaptation for analyzing complex problems. Psychol Rev. 2009;116(3):620–654. doi: 10.1037/a0016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in women: implications for health care research. Science. 1995;269(5225):799–801. doi: 10.1126/science.7638596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans-Campbell T, Lindhorst T, Huang B, Walters KL. Interpersonal violence in the lives of urban American Indian and Alaska Native women: implications for health, mental health, and help-seeking. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1416–1422. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bohn DK. Lifetime physical and sexual abuse, substance abuse, depression, and suicide attempts among Native American women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2003;24(3):333–352. doi: 10.1080/01612840305277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malcoe LH, Duran BM, Montgomery JM. Socioeconomic disparities in intimate partner violence against Native American women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2004;2(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bachman R, Zaykowski H, Lanier C, Poteyeva M, Kallmyer R. Estimating the magnitude of rape and sexual assault against American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women. Aust N Z J Criminol. 2010;43(2):199–222. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amnesty International British Section. Maze of Injustice: The Failure to Protect Indigenous Women From Sexual Violence in the USA. New York, NY: Amnesty International USA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sapra KJ, Jubinski SM, Tanaka MF, Gershon RRM. Family and partner interpersonal violence among American Indians/Alaska Natives. Inj Epidemiol. 2014;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2197-1714-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the American Indian or Alaska Native adult population: United States, 2004–2008. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;(20):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams PF, Kirzinger WK, Martinez ME. Summary health statistics for the US population: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. Vital Health Stat 10. 2013;(255):1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis DD, Keemer K. A brief history of and future considerations for research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. In: Davis JR, Erickson JS, Johnson SR, editors. Work Group on Native American Research and Program Evaluation Methodology (AIRPEM), Symposium on Research and Evaluation: Lifespan Issues Related to Native Americans/Alaska Natives With Disabilities. Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University, Institute for Human Development, Arizona University Center on Disabilities, Native American Rehabilitation Research and Training Center; 2002. pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(suppl 1):S104–S117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Les Whitbeck B, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Adams GW. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: culturally specific risk and resiliency factors for alcohol abuse among American Indians. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(4):409–418. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aguirre RTP, Watts TD. Suicide and alcohol use among American Indians: toward a transactional–ecological framework. J Comp Soc Welfare. 2010;26(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]