Abstract

Action to address workforce functioning and productivity requires a broader approach than the traditional scope of occupational safety and health. Focus on “well-being” may be one way to develop a more encompassing objective. Well-being is widely cited in public policy pronouncements, but often as “. . . and well-being” (e.g., health and well-being). It is generally not defined in policy and rarely operationalized for functional use. Many definitions of well-being exist in the occupational realm. Generally, it is a synonym for health and a summative term to describe a flourishing worker who benefits from a safe, supportive workplace, engages in satisfying work, and enjoys a fulfilling work life. We identified issues for considering well-being in public policy related to workers and the workplace.

Major changes in population demographics and the world of work have significant implications for the workforce, business, and the nation.1–8 New patterns of hazards, resulting from the interaction of work and nonwork factors, are affecting the workforce.1,2,8–11 As a consequence, there is a need for an overarching or unifying concept that can be operationalized to optimize the benefits of work and simultaneously address these overlapping hazards. Traditionally, the distinct disciplines of occupational safety and health, human resources, health promotion, economics, and law have addressed work and nonwork factors from specialized perspectives, but today changes in the world of work require a holistic view.

There are numerous definitions of well-being within and between disciplines, with subjective and objective orientations addressing such conceptualizations as happiness, flourishing, income, health, autonomy, and capability.12–22 Well-being is widely cited in public policy pronouncements, but often in the conjunctive form of “. . . and well-being” (as in health and well-being). It is rarely defined or operationalized in policy.

In this article, we consider if the concept of “well-being” is useful in addressing contemporary issues related to work and the workforce and, if so, whether it can be operationalized for public policy and what the implications are of doing so. We discuss the need to evaluate a broad range of work and nonwork variables related to worker health and safety and to develop a unified approach to this evaluation. We discuss the potential of well-being to serve as a unifying concept, with focus on the definitions and determinants of well-being. Within this part of the discussion, we touch on topics of responsibility for well-being. We also explore issues of importance when one is incorporating well-being into public policy. We present examples of the incorporation of the principles of well-being into public policy, and the results thus far of the implementation of such guidance. We describe research needs for assessing well-being, particularly the need to operationalize this construct for empirical analysis. We aim to contribute to the ongoing efforts of occupational safety and health and public health researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to protect working populations.

NEW PATTERNS OF HAZARDS

Many of the most prevalent and significant health-related conditions in workers are not caused solely by workplace hazards, but also result from a combination of work and nonwork factors (including such factors as genetics, age, gender, chronic disease, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and prescription drug use).9,11 One manifestation of this interaction of work and nonwork risks is the phenomenon known as presenteeism—diminished performance at work because of the presence of disease or a lack of engagement—which appears to be the single largest cause of reduced workforce productivity.23–26 Chronic disease is also a major factor in worker, enterprise, and national productivity and well-being. The direct and indirect costs of chronic disease exceed $1 trillion dollars annually.27 Moreover, the costs of forgone economic opportunity from chronic disease are predicted to reach close to $6 trillion in the United States by 2050.27 Chronic disease places a large burden on employers as well as on workers.

Although the classic significant occupational hazards still remain, work is changing. Many transitions characterize the 21st century economy: from physical to more mental production, from manufacturing to service and health care. New ways of organizing—contracting, downsizing, restructuring, lean manufacturing, contingent work, and more self-employment1,2,5,6,18,28,29—affect many in the labor force, and heightened job uncertainty, unemployment, and underemployment also characterize work in the global marketplace.1,2,7,8,10,29

Increasingly, work is done from home. Sedentary work accounts for larger portions of time spent in the workplace.30 New employment relations and heightened worker responsibilities are manifest in what organizational theorists have termed the “psychological contract” to characterize the nature of employers’ and employees’ mutual expectations and perceptions of work production.1 It may be as Stone has concluded, that “[T]he very concept of workplace as a place and the concept of employment as involving an employer are becoming outdated in some sectors.”1(p.ix)

The demographics of the workforce are also changing. More immigrants and women are joining the labor force, and older workers (those aged 55 years and older) are now the largest and fastest-growing segment of the workforce.31–33 Immigrants are projected to make up roughly 23% of working-age adults by 2050,33–35 a demographic shift that has significant implications on and for public health. Among other issues, Latino immigrants suffer significantly higher workplace mortality rates (5.0 per 100 000) than all workers (4.0 per 100 000).33–35 There is growing participation of men and women in previously gender-segregated fields and the integration of 2.4 million veterans who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2011.33,36 In some countries, workers are voluntarily working later in life; in others, decreased dependency ratios require them to work longer.32,37,38 There also are many workers wanting to work but without the necessary skills to meet job requirements.39

THE UNIFYING CONCEPT OF WELL-BEING

With the seismic shifts occurring in the global economy, there is a need for a concept that unifies all the factors that affect the health of workers, as well as the quality of their working lives.40–44 Well-being may be such a concept and, furthermore, it could be addressed as either an outcome in and of itself that might be improved by the application of prevention or intervention strategies that target risk factors, or it may be looked at as a factor that influences other outcomes. For example, healthy well-being has been linked to such outcomes as increased productivity, lower health care costs, health, and healthy aging.37,38,45–48 Numerous studies have shown links between individuals’ negative psychological well-being and health.49,50 Conversely, evidence from both longitudinal and experimental studies demonstrates the beneficial impact of a positive emotional state on physical health and survival.51–53 In these contexts, well-being might be thought of as a factor that has an impact on various outcomes. In other contexts, well-being is the outcome. Studies have shown that working conditions, including such factors as stress, respect, work–life balance, and income, affect well-being.54–58

Well-being has been defined and operationalized in different ways, consistent with roles either as a risk factor or as an outcome. Depending on the context, the literature associating well-being with productivity, health care costs, and healthy aging is heterogeneous, of variable quality, and difficult to assess and compare. Nonetheless, there are well-designed studies in different disciplines that indicate the potential benefits of using and operationalizing the concept of well-being.12,15,31,45,49,59–61

The use of an overarching concept such as “well-being” in public policy may more accurately capture health-related issues that have shifted over the past 30 years along with changes in population demographics, disease patterns, and the world of work. These shifts, which include changes in the nature of work, the workforce, the workplace, and the growing impact of chronic disease, have resulted in complex issues that interact and do not fit neatly in 1 field or discipline, making them especially difficult to address.5,8,14,18

DEFINITIONS, DETERMINANTS, AND RESPONSIBILITY FOR WELL-BEING

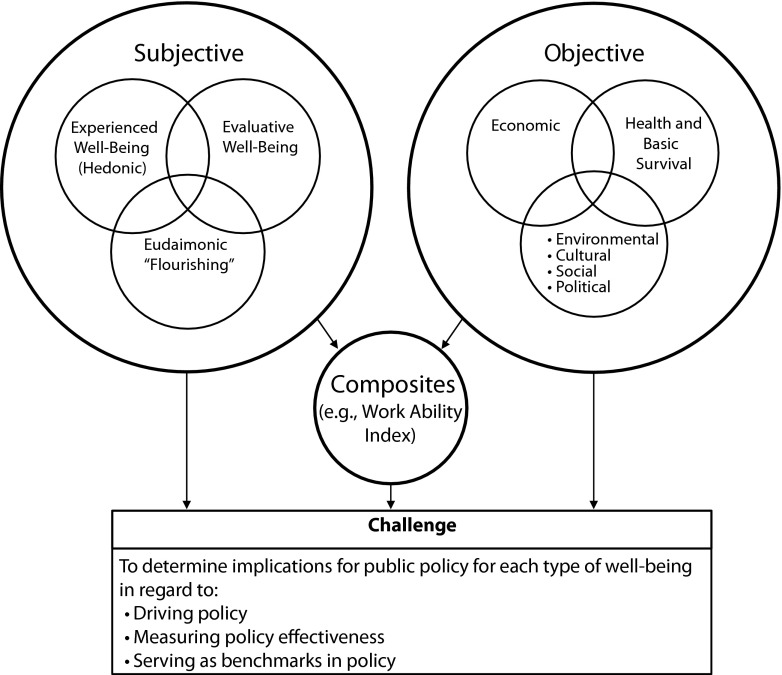

The published literature abounds with many definitions of well-being. These definitions may be objective, subjective (with a focus on satisfaction, happiness, flourishing, thriving, engagement, and self-fulfillment) or some synthesis of both.13,14,48,62–70 With regard to work, some definitions focus on the state of the individual worker, whereas others focus on working conditions, and some focus on life conditions. Figure 1 shows 3 major types of well-being—objective, subjective, and composite—and the policy challenges related to them.

FIGURE 1—

Types of well-being and policy challenges.

Note. Based on National Research Council 201366 and Xing and Chu 2014.68

Objective Well-Being

Defining and measuring well-being objectively for use in policy is to be able to make well-being judgments that are not purely subjective, that are independent of preferences and feelings, and that have some social agreement that such measures are basic components of well-being.69 Thus, having enough food, clothing, and shelter are rudimentary components of objective well-being. Their absence correlates with lack of well-being. For workers, income, job opportunity, participation, and employment are examples of components or facets of objective well-being. For companies, absenteeism, presenteeism, workers’ compensation claims, and productivity are objective indicators of well-being. The importance of measuring well-being with an objective index has been expressed in philosophical debates on distributive justice.71–73 If well-being is measured objectively, its index applies to everybody in the workforce so levels of well-being can be compared.66 However, when objective well-being is assessed by using “objective lists,” there are questions of what should be on the list and how it should be ordered.67 Objective well-being has various domains. Xing and Chu identified 6 major domains of objective well-being: health and basic survival, economic, environmental, cultural, social, and political (Figure 1).68

In recent years, the use of objective measures of well-being has been questioned and a call has been made for more overarching indicators of well-being.70,72,74 This is in part attributable to the fact that objective well-being indicators, such as economic ones, do not always adequately portray the quality of life. In 1974, Easterlin demonstrated that increases in income do not match increases in subjective well-being.75 This is because people’s aspirations change in line with changes in their objective circumstances.67

Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being is multifaceted and includes evaluative and experienced well-being (hedonic) and eudaimonic well-being, which refers to a person’s perceptions of meaningfulness, sense of purpose, and value of his or her life.66 Subjective well-being as originated by Warr has been described as assessable on 3 axes: displeasure-to-pleasure, anxiety-to-comfort, and depression-to-enthusiasm.76 Research has shown that subjective well-being measures relate in a predictable manner to physiological measures, such as cortisol levels and resistance to infection.77 More specifically for the work environment, well-being can be described in a model that identifies job-specific well-being that includes people’s feelings about themselves, in their job, and more general feelings about one’s life, referred to as “context-free” well-being.76,78

If subjective well-being is to be used in policy, the measures of it have to be shown as valid, reproducible, and able to indicate “interpersonal cardinality” because individuals may interpret scales differently. Interpersonal cardinality means that when 2 persons rate their subjective well-being as, for example, “5 out of 10,” they mean the same thing.79 Consideration of subjective well-being raises the question of the extent that it is related to personality traits, emotions, psychological traits that promote positive emotions, and the relationship with health status.80 Subjective well-being also needs to be considered with regard to whether it changes across the life span and with aging. The main challenge with measuring subjective well-being is the different conclusions that can be drawn depending on the numbers of factors that are accounted for and then controlled for in the analysis.81 When considered for the workforce or workplace policy, the question arises, should well-being at work be separated from well-being generally? Moreover, if well-being is included in policy, how do countries and organizations move from policy to practice?81

In discussions of subjective well-being in relation to policy, the focus is often on the measurement of experienced well-being. The unique policy value of experienced well-being measures may not be in discovering how clearly quantifiable factors (such as income) relate to aggregate-level emotional states, but rather in uncovering relationships that would otherwise not be acted upon.66 For example, levels of activity or time use in domains such as commuting or exercise may have an impact on well-being in ways that are not easily captured by objective measures. Subjective well-being measures seem most relevant and useful for policies that involve assessment of costs and benefits when there are not easily quantifiable elements involved—for instance, government consideration of spending to redirect an airport flight path to reduce noise pollution, funding alternative medical care treatments when more is at stake than maximizing life expectancy, or selecting between alternative recreational and other uses of environmental resources.66

Thus far, evidence about interactions between experienced well-being and other indicators is inconclusive. For example, on the relationship between income and experienced well-being, Deaton and Stone noted that, at least cross-nationally, the relationship between aggregate positive emotions (here, meaning day-to-day experienced well-being) and per capita gross domestic product is unclear.82

Some authors have suggested that an important consideration in using subjective well-being as a national aggregate indicator of well-being is that it may then easily become manipulated in the reporting of well-being.83 Thus, it is suggested that there may be an inherent limitation in selecting subjective well-being as a target of policy in that its measurement may become unreliable or biased.

Ultimately, subjective well-being has not been recommended as a singular indicator of social well-being but rather as an additional indictor that can capture a range of factors that are difficult to quantify, which may have an impact on well-being.66 Thus, a subjective assessment of well-being should serve as a supplement to other key social statistics.

Composite Well-Being

Composite indicators of well-being combine objective and subjective indicators of well-being into a single measure or measures. The underlying premise of composite well-being is that both objective and subjective well-being are important, complementary, and needed in public policy development, implementation, and assessment. There are various examples of composite well-being. The Gallup–Healthways Index is a composite measure composed of 5 domains: life evaluation, emotional health, work environment, physical health, and basic access.38,84 Some of the domains are subjective, some are objective. More specific for work, the Work Ability Index (WAI) developed in the 1980s in Finland has been widely assessed and can be seen as a composite indicator of well-being. Its validity has been determined and it has been evaluated in numerous populations. Workability indicates how well a worker is in the present and is likely to be in the near future, and how able he or she is to do his or her work with respect to work demands, health, and mental resources.85 Use of the WAI in the Netherlands is an example of using composite well-being in policy. The Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs established in 2008 a program (Implementation of WAI in the Netherlands) to promote, understand, and use workability.86 A database of the use of the WAI and related job training, job designs, health, and career interventions to improve WAI is used to benchmark among sectors and is then used by policymakers to identify where more intervention is needed. Composite indicators of well-being in general are subject to the impact of the selection of indicators, high correlation between components, computational focus, and component weighting.70

A variant of the composite view of well-being is the simultaneous measurement of multiple aspects or domains of well-being.87 For example, a program designed to improve well-being in a retail workforce resulted in improvement of multiple domains of well-being measured independently as improved productivity and increased overall profitability.88 In another study, Smith and Clay showed that plotting at least 1 subjective and 1 objective measure of well-being can be used to compare activities at multiple scales and across nations, time, and cultures.87

Definitional Clarity and Measurement

There has been a marked tendency to think of well-being as a synonym for health or for mental health. However, broader definitions have been widely used. In addition to objective, subjective, and composite well-being definitions, well-being has been examined as either a risk factor for physical and mental health outcomes, or as an outcome impacted by personal, occupational, or environmental risk factors, or both at the same time. The definitions and resultant policy pronouncements involving well-being involve very diverse conceptualizations in terms of scale, scope, location, and responsibility.14,17,56,59,84 Although a single definition of well-being may not be needed, there is need for clarity and specification of the ones used to drive policy, as a component of policy, or to evaluate policy.65,81,89 There have been different focal formulations of well-being such as well-being at work, well-being of workers, employee well-being, workforce well-being, workplace well-being, and well-being through work. In some cases, the difference in focus may be merely semantics. However, the focus of well-being may influence determinants, measures, variable selections, interventions, and ultimately regulation and guidance. For “well-being” to be a useful concept in public policy, it has to be defined and operationalized so that its social and economic determinants can be identified and interventions can be developed so that inducements to “ill-being” in the activities and relations in which people participate can be addressed.90

Various tools, instruments, and approaches (e.g., questionnaires, databases, and economic and vital statistics) have been used to measure well-being. The type of measurement may depend on the type of well-being (i.e., objective, subjective, composite) and level of consideration (i.e., individual worker, enterprise, or national level). Warr91 identified 8 elements that should be addressed in measurement of well-being:

whether it should be seen from a psychological, physiological, or social perspective;

whether it should be viewed as a state (time specific) or a trait (more enduring);

its scope (i.e., type of setting or range);

whether to focus on the positive or negative aspects of well-being or a combination of both;

viewing them as indicators of affective well-being and cognitive–affective syndromes (i.e., considering feelings only or including perceptions and recollections);

what to assess when one is measuring affective well-being;

what to assess when one is measuring syndrome well-being; and

examining ambivalence, which includes the temporal aspects, at 1 point in time or across time.81

Determinants of Well-Being

The literature on determinants of well-being of the workforce as an outcome attributable to work-related factors is extensive and diverse.13,45,55,56,76,81 A large number of factors have been investigated and implicated.13,55,58,92–99 Chief among these are workplace management, employee job control, psychological job demands, work organization, effort and reward, person–environment fit, occupational safety and health, management of ill health, and work–life balance.

Using a longitudinal design and external rating of job conditions, Grebner et al. observed that job control (i.e., feelings of control over one’s work) correlated with well-being on the job, and job stressors correlated with lower well-being.95 Hodson identified the main structural determinants of worker well-being through a quantitative analysis of ethnographic accounts of 108 book-length descriptions of contemporary workplaces and occupations.56,57 Narrative accounts were numerically coded and analyzed through a multivariate analysis.56,57 The research determined that the strongest determinants of worker well-being were mismanagement, worker resistance (any individual or small group act to mitigate claims by management on employees or to advance employees’ claims against management), and citizenship (positive actions on the part of employees to improve productivity and cohesion beyond organization requirements).56,57

A large amount of literature has quantified job demands and control as they pertain to workers’ well-being defined by job stress.59,93–99 Well-being of workers has also been assessed by using the effort–reward imbalance model, which addresses the effort workers put into their jobs and the rewards they get. When the rewards comport with the efforts, well-being is increased.99 In 1979, Karasek suggested that jobs be redesigned to include well-being as a goal.93 The relationship of well-being in terms of health has been assessed with regard to job insecurity, work hours, control at work, and managerial style.8,89,91,92 Well-being at work has also been assessed in terms of factors such as work–life balance, wages, genes, personality, dignity, and opportunity.54–57,76,100–104

Another approach used in vocational psychology and job counseling to assess determinants of well-being is the use of “person–environment” fit models. These models make the simple prediction that the quality of outcomes directly reflects the degree to which the individual and the environment satisfy the other’s needs. The Theory of Work Adjustment has detailed a list of 20 needs common, at varying degrees, to most individuals and most workplaces.105,106 It also outlines the mechanics and dynamics of this interaction between person and environment to make predictions about outcomes and it is one of the few models that give equal weight to satisfaction of the worker and the workplace (most approaches emphasize one at the expense of the other—or even ignore one entirely).

In yet another approach, macroergonomics evolved to expand on the traditional ergonomics of workstations and tool design, workspace arrangements, and physical environments.107,108 Macroergonomics addresses the work organization, organizational structures, policies, climate, and culture as upstream contributors to both physical and mental health. This approach helps to translate concepts of well-being to specific job sites.106,107 Ultimately, if well-being of the workforce is to be achieved and maintained, the policies and guidance need to be practical and feasible at the job level.109

The well-being of the workforce is dependent not only on well-being in the workplace, but also on the nonwork determinants of well-being. These determinants include personal risk factors (e.g., genetics, lifestyle) as well as social, economic, political, and cultural factors. The challenge in accounting for these may not be to use every factor but to select factors that are surrogates for or represent constellations of related determinants.

Responsibility for Well-Being

Well-being is a summative characteristic of a worker or workforce and it can also be tied to place, such as to the attributes of the workplace.17,43,80 In part, achieving increased well-being or a desired level of well-being of the worker and the workforce is inherent in the responsibility of the employers to provide safe and healthful work. However, because well-being is a summative concept that includes threats and promoters of it, as well as nonwork factors, the worker (employee) has a responsibility, too. Clearly, this overlapping responsibility is a slippery slope that could lead to blaming the worker for decreased well-being. Thus, it may be necessary to distinguish work-related from non–work-related sources of well-being and to identify the apportionment of responsibility. This is a new and challenging endeavor. The standard practice in occupational safety and health is that the employer is responsible for a safe and healthy workplace and the employee is responsible for following appropriate rules and practices that the employer establishes to achieve a safe and healthy workplace.

If a higher-level conceptualization of well-being is pursued, which subsumes health, is aspirational, and includes reaching human potential, then workers surely must actively engage in the process. How the roles of employer versus employee will be distinguished, and what to do about areas of overlap, are critical questions that need to be addressed. In addition, although well-being at work may be primarily an employer’s responsibility, well-being of the worker or workforce is also the responsibility (or at least in the purview) of others in society (e.g., governments, insurance companies, unions, faith-based and nonprofit organizations) or may be affected by nonwork domains. Clearly, the well-being of the workforce extends beyond the workplace, and public policy should consider social, economic, and political contexts.

ISSUES FOR INCLUDING WELL-BEING IN PUBLIC POLICY

Two critical policy considerations address the incorporation of well-being for workers in public policy issues. First is the question of how well-being will be used, and second is what actions should be taken to reduce threats to well-being and increase promotion of it. The initial need is to consider the question of how the concept will be used. Will well-being be an end (dependent variable), a means to an end (independent variable), or an overarching philosophy? The dominant observation of this article is that well-being in policy has been used as an overarching philosophy. The 1998 Belgian Legislation on the policy of well-being of workers at work is such an example. It pertains to

work safety;

health protection of the worker at work;

psychosocial stress caused by work including violence, bullying, and sexual harassment;

ergonomics;

occupational hygiene; and

establishment of the workplace, undertaking measures relating to the natural environment in respect to their influence on points 1 through 6.110,111

For the most part, this decree mandates what is considered as the current practice of occupational safety and health. This example does not capture some components of well-being such as self-fulfillment, engagement, flourishing, and opportunity often found in many definitions. Even if it did, this use as an overarching philosophy may serve to drive policy but does not necessarily identify or address determinants or measures of whether well-being is achieved.

If well-being is considered as a policy objective, then its presence or degree needs to be measurable. Are there attributes of well-being that could be defined and ultimately measured? Numerous instruments for measuring well-being in general and some for well-being in the workplace have been developed.22,38,45,66,85,111,112 Sometimes the measurements are surrogates or components of well-being (such as longer careers, health, or productivity); other times they involve the capacity to attain well-being (such as income, job control, and autonomy).63,113–117

In terms of work, well-being could be described in terms of the worker overall, at work and outside work. It can be considered in terms of the workforce as a whole, by sector, by enterprise, and by geographic designation. The consideration of well-being at work could be addressed in public policy through performance or specification approaches. The “performance” approach would stipulate an end state, possibly a state of well-being demonstrated by positive indicators (e.g., worker engagement, decreased absenteeism, increased productivity, decreased bullying, or harassment); however, the means to that end would not be specified. By contrast, in a “specification” approach, the means to achieve an end would be specified.

Actions to Reduce Threats to, and Increase Promotion of, Well-Being

The second critical policy question is what actions should be taken to reduce threats to well-being of workers and increase promotion of it. This will in part need to be addressed in terms of where regulatory authority circumscribes the actions that must be taken to protect workers and prevent workplace disease, injury, and deaths. Therefore, in the United States, the focus would be on the Occupational Safety and Health Act, the Mine Safety and Health Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, and other legislation that has worker safety and health provisions.

The definition of health in work-related legislation has generally been narrowly originated to be the absence of disease. If, however, a broader definition of health, such as the one promoted by World Health Organization (WHO)118 is used, well-being is a central component. The WHO definition is “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”118(p1) As a consequence, using this definition of health alters the interpretation of legislation dealing with workers’ health. However, one of the unintended interpretations of the WHO definition is that, in the era of chronic disease, a goal of complete well-being could lead to the “medicalization of society” where many people would be considered unhealthy most of the time because they lack complete well-being. If the WHO definition is reformulated to a more dynamic view, “based on the resilience or capacity to cope and maintain one’s integrity, equilibrium and sense of well-being,” it would better be a focus for public policy.119(p2)

In addition, in some of the current legislation, there is the implication to go beyond health and address broader issues of well-being. For example, in the United States, the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act (Pub. L. No. 91-596, 84 STAT. 1590, December 29, 1970) also mandates the preservation of human resources, although interpreting this statement broadly to include “well-being” was probably not the original legislative intention; its inclusion, however, is consistent with considering a range of factors influencing workers’ well-being. Although this extant legislation could be sufficient, it may be that additional legislation or consensus standards are needed that will identify responsibilities for achieving or maintaining workforce well-being.

Well-Being as a Driver of Public Policy

In addition to being included in public policies, well-being assessments may be used to affect or drive public policy.65,89,120 They may serve as part of a feedback loop on existing conditions or policies to define success, failure, or the need for modification of them.89,121 Because worker well-being is a multifactorial concept, it may be important to understand which aspect of well-being is affected by specific policies or conditions.18,88,89 For example, one of the best surveys related to well-being of workers is the European Working Conditions Survey, which was first conducted in 1990 and periodically repeated in 16 countries.112 This household survey addresses a broad range of themes, which taken together can be seen as describing well-being in a broad sense of the term. Many of the individual themes of the survey involve various components of well-being and are strong predictors of well-being.112,113 These themes include employment status, working time duration, safety, work organization, work–life balance, worker participation, earnings, and financial security, as well as work and health. The results of this survey are periodically compared for 16 European Nations. Use of the survey in the United States would be a useful way to identify a baseline on well-being that could serve to drive public policies as well as serve as a comparison over time. Although this survey is a useful tool, it is subjective and only addresses well-being from the worker perspective. There is also need for tools to assess well-being from the societal perspective.

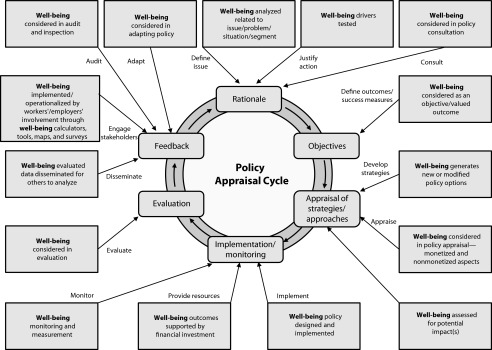

Well-being can also be used to screen public policies. Screening can assess whether a policy will have an effect on workforce well-being or its drivers.89 It is also worth reflecting on at what stage in policy development and appraisal it is best to consider well-being. Allin identified stages of a broad policy appraisal cycle and incorporated a well-being perspective.89 Figure 2 traces the steps for developing, implementing, and evaluating policy. Well-being can be considered at each step in various ways.

FIGURE 2—

Worker/workforce well-being and the policy appraisal cycle.

Note. Adapted from Allin 2014.89

EXAMPLES OF THE USE OF WELL-BEING IN PUBLIC POLICY OR GUIDANCE

Various efforts illustrate application of the well-being concept in policies, guidance, and research (Table 1). The WHO document “Healthy workplaces: a model for action: for employers, workers, policy-makers, and practitioners” uses the concept of well-being as a foundation.125 Building on the WHO definition of health,118 the document defines a healthy workplace as one in which workers and managers collaborate to use a continual improvement process (based on the work of Deming128) to protect health, safety, and well-being of all workers and the sustainability of the workplace. Four areas identified for actions that contribute to a healthy workplace include the physical work environment, the psychosocial work environment, personal health resources in the workplace, and enterprise community involvement.

TABLE 1—

Examples of Well-Being in Research, Guidance, and Regulation

| References (Year) | Use | Conception or Definition of Well-Being | Focus or Methods | Metrics or Indicators |

| Research | ||||

| Harter et al.38 | Relationship to business outcomes | “We see well-being as a broad category that encompasses a number of workplace factors. Within the overall category of well-being we discuss a hypothesized model that employee engagement (a combination of cognitive and emotional antecedent variables in the workplace) generates higher frequency of positive affect (job satisfaction, commitment, joy, fulfillment, interest, caring). Positive affect then relates to the efficient application of work, employee retention, creativity, and ultimately business outcomes.”(p2-3) | Meta-analysis of 36 companies involving 198 514 respondents | Employee engagement linked business outcomes |

| Chida and Steptoe50 | Relationship to mortality | “Positive psychological well-being encompasses positive affect and related trait-like constructs or dispositions, such as optimism. . . . Positive affect can be defined as a state of pleasurable engagement with the environment eliciting feelings, such as happiness, joy, excitement, enthusiasm, and contentment.”(p741) | Systematic review of prospective cohort studies to determine link between well-being and mortality | 35 studies, hazard ratio = 0.82; 95% confidence interval = 0.76, 0.89 |

| Huppert et al.121 | European Social Survey | “Well-being is a complex construct.”(p303) It is “people’s perceived quality of life, which we refer to as their ‘well-being.’”(p302) | Well-being module and questionnaire | 54 items, divided into 2 sections, corresponding to personal and interpersonal dimensions of well-being; each of these is further subdivided into feeling (being) and functioning (doing) |

| Guidance or practice | ||||

| Delwart et al.122 | Well-being in the workplace guide | Identify best practices related to well-being in the workplace | Key performance indicators | |

| Schill and Choosewood123 | Guidance for Total Worker Health | “Total Worker HealthTM is a strategy integrating occupational safety and health protection with health promotion to prevent worker injury and illness and to advance health and well-being.”(pS8) “Promoting optimal well-being is a multifaceted endeavor that includes employee engagement and support for the development of healthier behaviors, such as improved nutrition, tobacco use/cessation, increased physical activity, and improved work/life balance.”(pS9) |

Guidance on how to integrate health protection and promotion | Various score cards |

| Canadian Standards Association124 | Mental well-being guidelines | Psychological health and safety in the workplace | Developing an action plan for implementing the mental health and well-being strategy | Integrated approach |

| Burton125 | WHO model for healthy workplace | “WHO’s definition of health is: ‘A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease.’ In line with this, the definition of a healthy workplace . . . is as follows: A healthy workplace is one in which workers and managers collaborate to use a continual improvement process to protect and promote the health, safety, and well-being of all workers and the sustainability of the workplace.”(p90) | Framework for health protection and promotion | Continuous improvement method |

| Regulation or policy | ||||

| Pot et al.116 | WEBA (conditions of well-being at work policy) | Operational well-being in terms of organization of work and ergonomics | How to measure individual well-being | 3 value levels for 7 questions |

| East Riding of Yorkshire Council126 | Psychological well-being at work policy | The mental health as well as the physical health, safety, and welfare of employees | Stress assessment (relating to work pressures) tool to develop action plan | Likert-like scoring |

| Risk scoring | ||||

| Ministry of Social Affairs and Health127 | Well-being at work policies | “Health, safety and well-being are important common values, which are put into practice in every workplace and for every employee. The activities of a workplace are guided by a common idea of good work and a good workplace. Good work means a fair treatment of employees, adoption of common values as well as mutual trust, genuine cooperation and equality in the workplace. A good workplace is productive and profitable.”(p4) | Policies to specify a ministerial strategy | Extend work 3 y |

| “From the perspective of the work environment, a good workplace is a healthy, safe and pleasant place. Good management and leadership, meaningful and interesting tasks, and a successful reconciliation of work and private life are also characteristics of a good workplace.”(p4) | Reduce workplace accidents 25% | |||

| Reduce psychic strain 20% | ||||

| Reduce physical strain 20% |

Note. WEBA = conditions of well-being at work; WHO = World Health Organization.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Total Worker Health program integrates occupational safety and health protection with workplace policies, programs, and practices that promote health and prevent disease to advance worker safety, health, and well-being.123,129 It thus explicitly focuses on both the workplace and the worker as well as on the dynamics of employment. There is a growing body of support for prevention strategies to combine health protection and health promotion in the workplace.109,123,129,130 The Total Worker Health program is an expanded view of human capital, identifying what affects a worker as a whole rather than distinguishing between “occupational” and “nonoccupational realms.”129,130 The program calls for a comprehensive approach to worker safety, health, and well-being. Guidelines and frameworks are provided to implement policies and programs that integrate occupational safety and health protection with efforts to promote health and prevent disease.

In another effort, the recent Canadian consensus standard on mental health in workers illustrates a step in the direction of targeting psychological well-being as an outcome, and the means to achieve it.124 The stated purpose of this voluntary standard is to provide a systematic approach for creation of workplaces that actively protect the psychological health and promote the psychological well-being of workers. “Psychological well-being” is characterized by a state in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.124 To achieve this purpose, the standard details requirements for development, implementation, evaluation, and management of a workplace psychological health and safety management system (PHSMS). The standard enumerates 13 workplace factors that affect psychological health and safety and uses these factors to guide the conceptualization of a PHSMS. Risk management, cost effectiveness, recruitment and retention, and organizational excellence and sustainability are included in the business case rationale for a comprehensive and effective PHSMS. In addition to an outcome of improved well-being, benefits for workers from a PHSMS include improved job satisfaction, self-esteem, and job fulfillment.124

Additional examples regarding the use of the term “well-being” can be found in a number of European policies.111 In the Netherlands, guidance was issued in 1989 that called for well-being in the workplace. This legislation operationalized well-being in 2 categories: organization of work and ergonomics. It also required the training of a “new” type of professional at the master’s degree level with expertise in organization of work.116 However, after a few years, the legislation was challenged because of difficulty in enforcing the subjective concept of well-being, and nullified by the courts. During that period, an instrument to assess job content, known as the WEBA instrument (well-being at work), was developed to assess stress, risks, and job skill learning opportunities. This instrument is based on the Karesek93 demand–control theory and innovation guidance.116

A broader illustration is the Finnish Policy, “Work Environment and Well-Being at Work Until 2020,” which identifies attainment of well-being through lengthened working life, decreased accidents and occupational diseases, and reduced physical and psychic strain.127 The Finnish policy of well-being at work aims to encourage workers to have longer work careers:

This means improving employees’ abilities, will, and opportunities to work. Work must be attractive and it must promote employees’ health, work ability, and functional capacity. Good and healthy work environments support sustainable development and employees’ well-being and improve the productivity of enterprises and the society.127(p5)

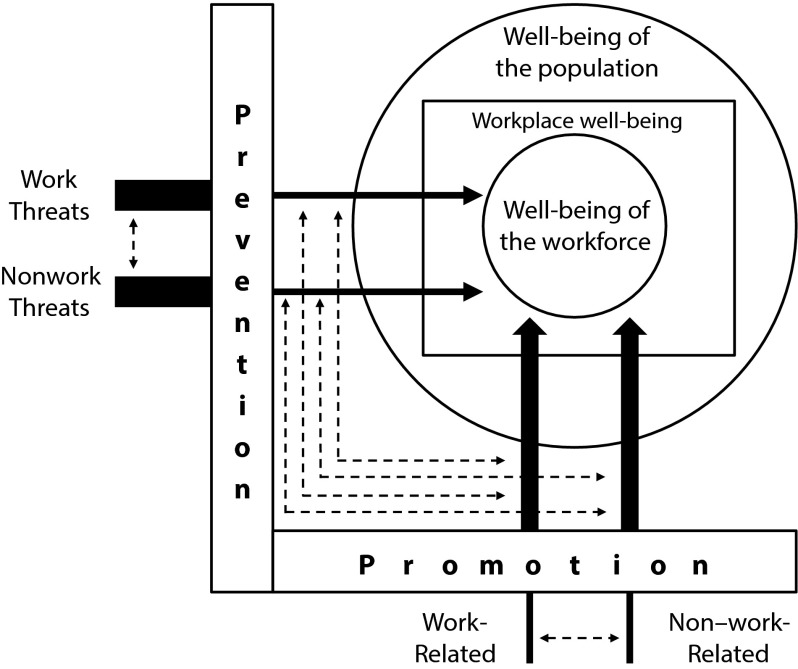

This article focuses on public policy related to well-being and the application of that policy to workers and the workplace and for the workforce overall. As shown in Figure 3, there are work and nonwork threats to, and promoters of, well-being. Preventing workplace hazards and promoting workers’ well-being in that context necessitates policies that cross work–nonwork boundaries. This is exemplified in the WHO “healthy workplaces model”125 and in the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Total Worker Health program.123 Although both acknowledge the nonwork influences, they primarily illustrate how to address them in the workplace. Clearly, as has been illustrated in the aftermath of the effort to enact “well-being” legislation in the Netherlands, ensuring well-being in the workplace is difficult to mandate because of various issues related to measurement, responsibility, motivation, and cost.116 Nonetheless, there are examples of companies worldwide that have promoted holistic well-being approaches.41,87,114,122,130

FIGURE 3—

Conceptual view of the possible relationship between work and nonwork threats to, and promotors of, well-being.

Note. Dashed lines show interaction of factors.

The strong link of well-being to productivity and health is a motivating factor for a business strategy that includes well-being considerations.37,38,45,122,130–132 The key, however, is to integrate health protection and health promotion in interventions in the workplace.123 Although the focus has initially been on physical health, the greater impact may be on mental and social health and well-being overall.132–136 Employers have found that it is beneficial to go beyond a physical health focus to affect productivity because recruitment, retention, and engagement of employees include consideration of work–life balance, community involvement, and employee development.111,133,135,136

The implementation of programs for well-being at work has been described in various countries and for various sizes of companies.45,111,133–135 Though generally not explicit about the definition of well-being, the programs involve raising awareness in a company, creating a culture and environment that will promote practice for well-being, and using a means to measure and consider changes in well-being or its components and determinants. One necessary aspect that is not often highlighted in implementing well-being policies is the need for worker participation.107 Worker input on policies and processes that affect them is critical for the effectiveness of those efforts.

From a business perspective, implementation of well-being programs should be considered as an investment rather than a cost.129,137 However, as Cherniack notes,

the concept of return on investment for a workplace intervention is incongruous with the more usual approach in health research of comparative effectiveness, where interventions are compared between nonamortized outcomes or comparable outcomes are assessed by program costs.138(p44)

Nonetheless, the business value of well-being programs is critical information.38,45,47,131,132 To this end, efforts to develop and implement well-being policies should promote the business value of such policies along with the philosophical and humanitarian aspects.45,47,131,134

Well-being at work has implications not only for the worker and the company but also for the workforce as a whole, for the population, and for the national economy.43,45,133,134,139 Restricting consideration of well-being to the workplace does not capture the full importance and meaning of work in human life. Budd and Spencer have advocated that

[a] more complete approach to worker well-being needs to go beyond job quality to consider workers as fully-functioning citizens who derive and experience both public and private benefits and costs from working.46(p3)

Too often worker well-being is considered at the level of worker health, job quality, and satisfaction. However, interviews with workers about their perceived well-being found that many emphasized specific job characteristics, and many also focused on the extent to which work enabled them to live in their chosen community and attain or maintain their preferred lifestyle.46,140 The extent to which this sentiment is generalizable to a broad range of workers is not known, but it is clear that job quality and worker well-being has a socioeconomic context that should be considered in the development of public policy and implementation of well-being programs.46,84,102

RESEARCH AND OPERATIONALIZATION NEEDS

Although there is a foundational literature on the relationship between worker well-being and enterprise productivity,37,38,45,132,135,136,139 the link has yet to be analyzed systematically and bears further investigation.13 In addition, the relationship between workforce well-being and population well-being needs to be further elaborated to provide the impetus for the development of policies and practices to support programs that enhance well-being.43 Workforce well-being historically has not always been viewed as central to national welfare.43,46 This is despite the fact that the workforce makes up the largest group in the population (when compared with the prework and postwork groups). There is also need for research on the creation of good jobs. A large number of “good” jobs and the ability of the workforce to access them, move between them, and otherwise thrive is critical to the well-being of the entire population.29,48,141

There is also a need for a strategy for conducting research to fill gaps in the evidence base for what works and does not work in achieving or maintaining well-being. These efforts will hinge on clarifying the constituent factors that contribute to well-being, as well as on identifying promising interventions to address or enhance well-being. Many of the challenges related to conceptualizing and operationalizing well-being may prove intractable, including addressing issues linked to distribution of opportunity and income, lack of job control, organization of work, and potential conflicts caused when or if guidance for promoting worker well-being is perceived as interfering with employers’ rights to manage their workplaces.142 Nonetheless, as described earlier in this article, the Canadian mental health standard shows that many of these barriers are not insurmountable.124 An important focus of research is how to address these seemingly intractable challenges linked to promoting well-being.

It may be desirable to include well-being in public policy, but several challenges exist to achieving this end. Empirical research and analysis require the development of standard definitions, operationalized variables that can be measured, and an understanding of the implications of using such definitions and metrics.15,17,19,143,144 Hypothesis testing of the determinants and impacts of well-being, based on operationalization of definitions and associated metrics, moves the researcher from the abstract to the empirical level, where variables—rather than concepts or definitions—are the focus.143 If variables that describe aspects of well-being can be measured and agreed upon, this might allow the determination of targets for intervention or improvement. Analysis of the determinants and impacts of well-being for public policy need to be multilevel because well-being is affected by political, economic, and social factors.18,68,89,99,144

One of the drivers of public policy aimed at occupational safety and health is quantitative risk assessment.145 Quantitative risk assessment is statistical modeling of hazard exposure–response data to predict risks (usually) at lower levels of exposure. One question is whether approaches from classic quantitative risk assessment are useful in assessing well-being in the occupational setting as a basis for policy. To apply risk assessment methods to well-being, an “exposure–response” analog would be needed. For example, the exposures could be threats to well-being and the response the state of well-being influenced by those threats, or exposures could be a certain type of well-being and the response could be markers of health.

A number of issues arise in the conceptualization of an exposure–response relationship related to well-being. First, threats to well-being can come from various sources related to work and external to it. Identifying them and combining them into an exposure variable with an appropriate, tractable metric will be difficult. If the focus is for employer and worker or workforce guidance, it is likely that the threats pertaining to the workplace will be most relevant, but external nonwork threats will also be important, and the 2 may interact (Figure 3). Capturing that interaction will be difficult and complicated but it is critical if well-being is to be included in risk assessment.

Second, there are factors that promote well-being, such as work, having a job, and adequate income.134,146,147 A job that is satisfying is even more so associated with well-being.48,148 Third, identifying and operationalizing the promoters of or threats to well-being will be a challenge. If this can be accomplished then perhaps exposure–response relationships relevant to well-being can be identified and quantified. It may then be appropriate to identify on an “exposure–response curve” an (adverse) change in the “amount” of well-being, or other outcome affected by well-being, that may be considered to be of importance in a given context. This may then allow the derivation of a level of a relevant exposure associated with the defined change in outcome, consistent with the application of the quantitative risk assessment paradigm. If exposures (positive and negative) could be assessed, then desirable targets could be specified. Ultimately, the need will be to determine a level of risk for either decreased well-being or outcomes impacted by well-being in the workplace, the workforce, and for individual workers to define targets for intervention and prevention strategies.

If a risk assessment approach is appropriate to examine well-being for the development of public policy, one underlying question is whether it is feasible to develop an exposure–response analog for well-being. Various aspects of well-being would need to be taken into consideration. These include the fact that well-being has both subjective and objective attributes. How do you measure these across various work settings and conditions?149,150 How do you adjust for subjective differences?16 In addition, well-being is not a static condition; it is an evolving one that changes with time and other factors.17,151 Although the focus thus far has been on well-being as the target of policy, it may be that well-being also should be seen as a means to achieve policy.64 If the latter view is the case, does this change any of the definitional and variable specification issues raised thus far? For example, the issue of well-being as a changing condition might be the rationale for identifying trends in workforce well-being as outcomes of policies or interventions. As a consequence, leading indicators of well-being outcomes might be sought and used as targets for guidance or regulation.

If well-being is to be incorporated in quantitative risk assessments, it would need to be evaluated for whether it meets the basic quantitative risk assessment criteria. These include whether

hazards (threats) to well-being can be defined and measured;

well-being can be defined and measured when it is functioning as a factor that has an impact on health outcomes;

well-being as an outcome or response of exposure to these hazards (threats) can be defined and measured;

exposure–response models are appropriate for measuring well-being and whether these need to be quantitative, qualitative, or a combination thereof;

risk can be characterized and if it is possible to account for aspects such as uncertainty and sensitive populations; and

risk characteristics of threats to well-being can be used to drive risk-management strategies.

It may be that the exposure–response paradigm is not the appropriate way to think about and assess well-being. Qualitative approaches may be more relevant. For example, the European Union Well-Being at Work project promoted an approach developed by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, which described the management changes needed to achieve well-being at work and provided a self-evaluation matrix with 6 categories of activities that businesses can use to evaluate their performance.111,152 Or perhaps a combined quantitative and qualitative approach is the most appropriate for determining, addressing, or measuring the well-being of worker populations.

GOING FORWARD

The ultimate policy issue is whether it is a good idea to incorporate well-being as a focus for occupational risk assessments and guidance. The benefits of operationalizing well-being need further investigation, as do the unintended consequences. There are various policy issues that might come into play. Some of these have been described, including “blaming the worker” for lack of well-being in the workplace and diluting the responsibility of employers. The means of achieving well-being in the workplace are generally the responsibility of the employer, but true well-being requires that workers have autonomy and a role in determining the organization and conditions of work, have a living wage, and have an opportunity to share in the success of the organization. Clearly, these will be viewed by some as controversial issues, but they stem from what has been averred as inherent rights, even if they are not universally recognized.29,42,46,57,153,154

Eventually, consideration of well-being has to address ethical issues because various definitions of well-being could involve questions such as fair distribution of opportunity and realization of self-determination. It is understandable that there are political differences that arise over these issues. To help bridge some of these differences, there is need to expand the knowledge base described in this article for such aspects as the business case for promoting well-being at work, the link between workforce well-being and population well-being, and the need to address the range of determinants of well-being. The challenge in making workforce well-being a focus of public health and ultimately societal expectation is that it requires multiple disciplines and stakeholder groups to interact, communicate, and ultimately work together. This is not easy to achieve. In fact, it is quite difficult.

There is need for development of a strategy for cross-discipline and cross-stakeholder group multiway communication on this issue. The specialty discipline of occupational safety and health may be an appropriate initiator of these communications because its focus is solidly rooted in workforce safety, health, and, by extension, well-being. Other disciplines such as occupational health psychology, health promotion, industrial and organizational psychology, ergonomics, economics, sociology, geography, medicine, law, nursing, and public health also should be involved in the effort to examine well-being guidance and policies.

The focus on worker and workforce well-being is of critical national importance because of the role and significance of work to national life.43,132,134,152 The growing incidence of mental disorders, stress-related outcomes, and chronic diseases in the population and the organizational features of work related to safety and health outcomes require attention to their linkage to well-being. With dependency ratios becoming dangerously close to unsustainable levels and rising health care burdens, there is need for a more comprehensive view of what factors deleteriously affect the workforce and what can be done about it. Considering and operationalizing the concept of well-being is an important next step.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals for comments on earlier versions of this article: Frank Pot, Knut Ringen, Gregory Wagner, and Laura Punnett. We also acknowledge the efforts of Brenda Proffitt, Elizabeth Zofkie, and Devin Baker regarding logistical support in preparation of this article.

Human Participant Protection

No institutional review board approval was needed because the focus was literature based.

References

- 1.Stone KV. From Widgets to Digits: Employment Regulation for the Changing Workplace. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard J. Seven challenges for the future of occupational safety and health. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2010;7(4):D11–D18. doi: 10.1080/15459621003617898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kompier MA. New systems of work organization and workers’ health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):421–430. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulte PA. Emerging issues in occupational safety and health. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2006;12(3):273–277. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2006.12.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holzer HJ, Nightingale DS. Reshaping the American Workforce in a Changing Economy. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings KJ, Kreiss K. Contingent workers and contingent health—risks of a modern economy. JAMA. 2008;299(4):448–450. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitt M, Howard J. The face of occupational safety and health: 2020 and beyond. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(3):138–139. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparks K, Faragher B, Cooper CL. Well-being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2001;74(4):489–509. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulte PA, Pandalai S, Wulsin V, Chun H. Interaction of occupational and personal risk factors in workforce health and safety. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):434–448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillemin M. Lesser Known Aspects of Occupational Health [in French] Paris, France: L’Harmattan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandalai SP, Schulte PA, Miller DB. Conceptual heuristic models of the interrelationships between obesity and the occupational environment. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39(3):221–232. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringen S. Households, goods, and well-being. Rev Income Wealth. 1996;4:421–431. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danna K, Griffin RW. Health and well-being in the workplace: a review and synthesis of the literature. J Manage. 1999;25(3):357–384. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin de Chavez A, Backett-Milburn K, Parry O, Platt S. Understanding and researching wellbeing: its usage in different disciplines and potential for health research and health promotion. Health Educ J. 2005;64(1):70–87. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler M. Well-Being and Equity a Framework for Policy Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener E. The remarkable changes in the science of subjective well-being. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(6):663–666. doi: 10.1177/1745691613507583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleuret S, Atkinson S. Wellbeing, health and geography: a critical review and research agenda. N Z Geog. 2007;63(2):106–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng ECW, Fisher AT. Understanding well-being in multi-levels: a review. Health Cult Sc. 2013;5(1):308–323. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seligman MEP. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10–28. doi: 10.1159/000353263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrawal S, Harter JK. Well-Being Meta-Analysis: A Worldwide Study of the Relationship Between the Five Elements of Wellbeing and Life Evaluation, Daily Expenses, Health, and Giving. Washington, DC: Gallup; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warr P. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemp P. Presenteeism: at work—but out of it. Harv Bus Rev. 2004;82(10):49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bustillos AS, Ortiz Trigoso O. Access to health programs at the workplace and the reduction of work presenteeism: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(11):1318–1322. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182a299e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Perio MA, Wiegand DM, Brueck SE. Influenza-like illness and presenteeism among school employees. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(4):450–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johns G. Presenteeism in the workplace: a review and research agenda. J Organ Behav. 2010;31(4):519–542. [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeVol R, Bedroussian A, Charuworn A . An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tehrani N, Humpage S, Willmott B, Haslam I. What’s Happening With Well-Being at Work? London, England: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osterman P, Shulman B. Good Jobs America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C et al. Trends over 5 decades in US occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa G, Goedhard WJ, Ilmarinen J. Assessment and Promotion of Work Ability, Health and Well-Being of Ageing Workers. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrestha LB. Age Dependency Ratios and Social Security Solvency. Washington, DC: CRS Report for Congress; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flynn MA. Safety and the diverse workforce. Prof Saf. 2014;59:52–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passel JS, Cohn DV. US Population Projections: 2005–2050. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cierpich H, Styles L, Harrison R et al. Work-related injury deaths among Hispanics—United States, 1992–2006 (Reprinted from MMWR, vol 57, pg 597–600, 2008) JAMA. 2008;300(21):2479–2480. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waterstone ME. Returning veterans and disability law. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2010;85:1081–1132. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rissa K, Kaustia T. Well-Being Creates Productivity: The Druvan Model. Iisalmi, Finland: Centre for Occupational Safety and the Finnish Work Environment Fund; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Keyes CL. Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes: a review of the Gallup studies. In: Keyes CL, Haidt J, editors. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington, DC: American Psychology Association; 2003. pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kochan T, Finegold D, Osterman P. Who can fix the “middle-skills” gap? Harv Bus Rev. 2012;90:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int. 1996;11(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dewe P, Kompier M. Wellbeing and Work: Future Challenges. London, England: The Government Office for Science; 2008. Foresight mental capital and wellbeing project. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauer GF. Determinants of workplace health: salutogenic perspective on work, organization, and organizational change. Slide presentation at: Exploring the SOCdeterminants for Health. The 3rd International Research Seminar on Salutogenesis and the 3rd Meeting of the International Union for Health Promotion and Education Global Working Group on Salutogenesis; July 11, 2010; Geneva, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.salutogenesis.hv.se/files/bauer_g._genf.salutogen.wh.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 43.Schulte P, Vainio H. Well-being at work—overview and perspective. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36(5):422–429. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vainio H. Salutogenesis to complement pathogenesis—a necessary paradigm shift for well-being at work. Slide presentation at: 30th International Congress on Occupational Health; March 18–23, 2012; Cancun, Mexico.

- 45.Prochaska JO, Evers KE, Johnson JL et al. The well-being assessment for productivity: a well-being approach to presenteeism. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(7):735–742. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318222af48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Budd JW, Spencer DA. Worker well-being and the importance of work: bridging the gap. Euro J Indust Rel. 2014:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gandy WM, Coberley C, Pope JE, Wells A, Rula EY. Comparing the contributions of well-being and disease status to employee productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(3):252–257. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grawitch MJ, Gottschalk M, Munz DC. The path to a healthy workplace: a critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consult Psychol J Pract Res. 2006;58(3):129–147. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huppert FA. Psychological well-being: evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Appl Psychol. 2009;1(2):137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(7):741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol. 2011;3(1):1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howell RT, Kern ML, Lyubomirsky S. Health benefits: meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychol Rev. 2007;1(1):83–136. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noor NM. Work- and family-related variables, work–family conflict and women’s well-being: some observations. Community Work Fam. 2003;6(3):297–319. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karanika-Murray M, Weyman AK. Optimising workplace interventions for health and well-being: a commentary on the limitations of the public health perspective within the workplace health arena. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2013;6(2):104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hodson R. Analyzing Documentary Accounts (Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hodson R. Dignity at Work. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mellor N, Webster J. Enablers and challenges in implementing a comprehensive workplace health and well-being approach. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2013;6:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boehm JK, Peterson C, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky L. A prospective study of positive psychological well-being and coronary heart disease. Health Psychol. 2011;30(3):259–267. doi: 10.1037/a0023124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Warr P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental-health. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63(3):193–210. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Linley PA, Maltby J, Wood AM, Osborne G, Hurling R. Measuring happiness: the higher order factor structure of subjective and psychological well-being measures. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47(8):878–884. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kahneman D. Objective happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sen A. Capability and well-being. In: Nussbaum M, Sen AK, editors. The Quality of Life. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1993. pp. 30–54. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Atkinson S, Fuller S, Painter J. Well-Being and Place. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adler MD. Happiness surveys and public policy: what’s the use? Duke Law J. 2013;62(8):1509–1601. [Google Scholar]

- 66.National Research Council. Subjective well-being: measuring happiness, suffering, and other dimensions of experience. In: Stone AA, Machie E, editors. Paper on Measuring Subjective Well-Being in a Policy Framework. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dolan P, White MP. How can measures of subjective well-being be used to inform public policy? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2(1):71–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xing Z, Chu L. Proceedings of the 58th World Statistical Congress. Dublin, Ireland: International Statistical Institute; 2011. Research on constructing composite indicator of objective well-being from China mainland; pp. 3081–3097. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gaspart F. Objective measures of well-being and the cooperative production problem. Soc Choice Welfare. 1997;15(1):95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Otoiu A, Titan E, Dumitrescu R. Are the variables used in building composite indicators of well-being relevant? Validating composite indexes of well-being. Ecol Indic. 2014;46:575–585. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rawls J. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sen A. Development as Freedom. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen GA. Equality of what? On welfare, goods and capabilities. In: Nussbaum M, Sen AK, editors. The Quality of Life. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2009. Available at: http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/documents/rapport_anglais.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 75.Easterlin RA. Does economic growth improve the human lot? In: David PA, Reeder MW, editors. Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Warr P. Well-being and the workplace. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 392–412. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Marmot M. Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(18):6508–6512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hassan E, Austin C, Celia C . Health and Well-Being at Work in the United Kingdom. Cambridge, England: Rand Europe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bronsteen J, Buccafusco CJ, Masur JS. Well-being and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics; 2014. Research paper 707.

- 80.Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buffet MA, Gervais RL, Liddle M, Eechelaert L. Well-Being at Work: Creating a Positive Work Environment. Luxembourg City, Luxembourg: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deaton A, Stone AA. Two happiness puzzles. Am Econ Rev. 2013;103(3):591–597. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frey BS, Gallus J. Subjective well-being and policy. Topoi. 2013;32(2):207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rath T, Harter J, Harter JK. Wellbeing: The Five Essential Elements. New York, NY: Gallup Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Eskelinen L, Nygård C-H, Huuhtanen P, Klockars M. Summary and recommendations of a project involving cross-sectional and follow-up studies on the aging worker in Finnish municipal occupations (1981–1985) Scand J Work Environ Health. 1991;16(suppl 1):135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.ESF Age Network. Work Ability Index: a programme from the Netherlands. Available at: http://www.careerandage.eu/prevsite/sites/esfage/files/resources/Work-Ability-Index_1.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2015.

- 87.Smith CL, Clay PM. Measuring subjective and objective well-being: analyses from five marine commercial fisheries. Hum Organ. 2010;69(2):158–168. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rajaratnam AS, Sears LE, Shi Y, Coberley CR, Pope JE. Well-being, health, and productivity improvement after an employee well-being intervention in large retail distribution centers. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(12):1291–1296. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Allin P. Measuring well-being in modern societies. In: Chen PY, Cooper CL, editors. Work and Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Neubauer D, Pratt R. The 2nd public-health revolution—a critical-appraisal. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1981;6(2):205–228. doi: 10.1215/03616878-6-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Warr P. How to think about and measure psychological well-being. In: Sinclair RR, Wang M, Tetrick L, editors. Research Methods in Occupational Health Psychology: Measurement Design and Data Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge Academics; 2012. pp. 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rounds JB, Dawis RV, Lofquist LH. Measurement of person environment fit and prediction of satisfaction in the theory of work adjustment. J Vocat Behav. 1987;31(3):297–318. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Karasek R. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grebner S, Semmer NK, Elfering A. Working conditions and three types of well-being: a longitudinal study with self-report and rating data. J Occup Health Psychol. 2005;10(1):31. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular-disease—a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(10):1336–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dhondt S, Pot F, Kraan K. The importance of organizational level decision latitude for well-being and organizational commitment. Team Perform Manage. 2014;20:307–327. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands–resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–328. [Google Scholar]