Abstract

We have presented an analytic framework and 4 criteria for assessing when global health treaties have reasonable prospects of yielding net positive effects.

First, there must be a significant transnational dimension to the problem being addressed. Second, the goals should justify the coercive nature of treaties. Third, proposed global health treaties should have a reasonable chance of achieving benefits. Fourth, treaties should be the best commitment mechanism among the many competing alternatives.

Applying this analytic framework to 9 recent calls for new global health treaties revealed that none fully meet the 4 criteria. Efforts aiming to better use or revise existing international instruments may be more productive than is advocating new treaties.

The increasingly interconnected and interdependent nature of our world has inspired many proposals for new international treaties addressing various health challenges,1 including alcohol consumption,2 elder care,3 falsified/substandard medicines,4 impact evaluations,5 noncommunicable diseases,6 nutrition,7 obesity,8 research and development (R&D),9 and global health broadly.10 These proposals claim to build on the success of existing global health treaties (Table 1). The breadth of proposed obligations reflects the diverse regulatory functions that treaties are perceived to serve (Table 2).

TABLE 1—

Select List of Global Health Treaties

| Year Adopted | Treaty Name |

| 1892 | International Sanitary Convention |

| 1893 | International Sanitary Convention |

| 1894 | International Sanitary Convention |

| 1897 | International Sanitary Convention |

| 1903 | International Sanitary Convention (replacing 1892, 1893, 1894, and 1897 conventions) |

| 1912 | International Sanitary Convention (replacing 1903 convention) |

| 1924 | Brussels Agreement for Free Treatment of Venereal Disease in Merchant Seamen |

| 1926 | International Sanitary Convention (revising 1912 convention) |

| 1933 | International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation |

| 1934 | International Convention for Mutual Protection Against Dengue Fever |

| 1938 | International Sanitary Convention (revising 1926 convention) |

| 1944 | International Sanitary Convention (revising 1926 convention) |

| 1944 | International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation (revising 1933 convention) |

| 1946 | Protocols to Prolong the 1944 International Sanitary Conventions |

| 1946 | Constitution of the World Health Organization |

| 1951 | International Sanitary Regulations (replacing previous conventions) |

| 1969 | International Health Regulations (replacing 1951 regulations) |

| 1972 | Biological Weapons Convention |

| 1989 | Basel Convention on Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes |

| 1993 | Chemical Weapons Convention |

| 1994 | World Trade Organization Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures |

| 1997 | Convention on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines and Their Destruction |

| 1998 | Rotterdam Convention on Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade |

| 2000 | Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity |

| 2001 | Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants |

| 2003 | World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control |

| 2005 | International Health Regulations (revising 1969 regulations) |

| 2007 | United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities |

| 2013 | Minamata Convention on Mercury |

Note. Global health treaties are those that were adopted primarily to promote human health.

TABLE 2—

Examples of the Diverse Regulatory Functions Among Existing International Treaties

| Domestic Obligations | Foreign Obligations | |

| Positive Obligations | The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (2003) requires countries to restrict tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship | The International Health Regulations (2005) requires countries to report public health emergencies of international concern to the World Health Organization |

| The World Trade Organization's Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (1994) requires countries to protect patent rights | The Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946) requires countries to pay annual membership dues | |

| Negative Obligations | The International Convention on Economic, Social & Cultural Rights (1966) prohibits countries from interfering with a person’s right to the highest attainable standard of health | The Biological Weapons Convention (1972) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (1993) prohibit countries from using biological and chemical weapons, respectively |

| The Stockholm Convention (2001) prohibits countries from producing certain persistent organic pollutants | The Geneva Conventions (1949) prohibit countries from torturing prisoners of war |

But whether international treaties actually achieve the benefits their negotiators intend is highly contested.11–13 There are strong theoretical arguments on both sides, and the available empirical evidence conflicts. A recent review of 90 quantitative impact evaluations of treaties across sectors found some treaties achieve their intended benefits whereas others do not. From a health perspective, there is currently no quantitative evidence linking ratification of an international treaty directly to improved health outcomes. There is only quantitative evidence linking domestic implementation of policies recommended in treaties with health outcomes. For example, Levy et al. found that tobacco tax increases between 2007 and 2010 in 14 countries to 75% of the final retail price resulted in 7 million fewer smokers and averted 3.5 million smoking-related deaths; the World Health Organization recommended this policy as part of its MPOWER package of tobacco-control measures that was introduced to help countries implement the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.14 Evidence of treaties’ direct impact on other social objectives is extremely mixed.1

Even if prospects for benefits are great, international treaties are still not always appropriate solutions to global health challenges. This is because the potential value of any new treaty depends on not only its expected benefits but also its costs, risks of harm, and trade-offs.15 Conventional wisdom suggests that international treaties are inexpensive interventions that just need to be written, endorsed by governments, and disseminated. Knowledge of national governance makes this assumption reasonable: most countries’ lawmaking systems have high fixed costs for basic operations and thereafter incur relatively low marginal costs for each additional legislative act pursued. But at the international level, lawmaking is expensive. Calls for new treaties do not fully consider these costs. Even rarer is adequate consideration of treaties’ potentially harmful, coercive, and paternalistic effects and how treaties represent competing claims on limited resources.11,15

When might global health treaties be worth their many costs? Like all interventions and implementation mechanisms, the answer depends on what these costs entail, the associated risks of harm, the complicated trade-offs involved, and whether these factors are all outweighed by the benefits that can reasonably be expected. We reviewed the important issues at stake, and we have offered an analytic framework and 4 criteria for assessing when new global health treaties should be pursued.

COSTS OF INTERNATIONAL TREATIES

International treaty-making can be incredibly expensive, usually more so than other types of international commitment mechanisms, for example, political declarations, codes of practice, and resolutions, which government negotiators often take less seriously.16,17 The direct financial costs associated with drafting, ratifying, and enforcing international treaties include not only many meetings, air travel, and legal fees but also potentially new duplicative governance structures—namely, conferences of parties, secretariats, and national focal points—which must be maintained. It is particularly this need for new governance structures that makes international treaties different from their national equivalents, which typically benefit from relatively higher functioning and more centralized regulatory systems that have already been established for administering, coordinating, and implementing them.15 Indirectly, there are nonfinancial opportunity costs in focusing limited resources, energy, and rhetorical space on 1 particular issue and approach, which requires other important initiatives to be shelved.18

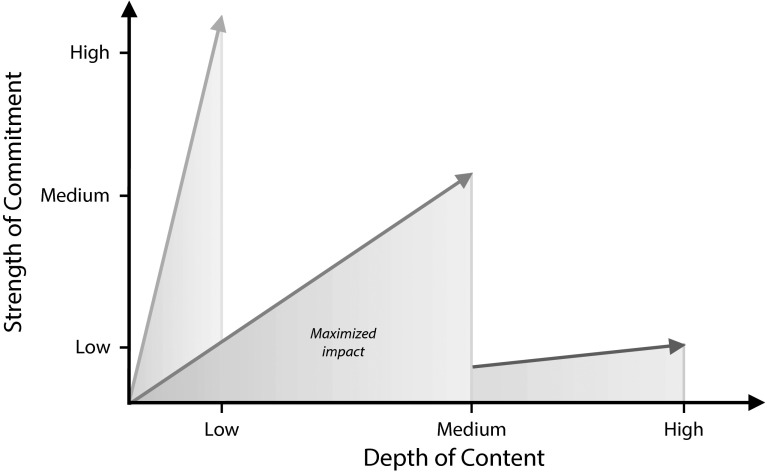

The legalization of global health issues otherwise left in the political domain may have the additional consequence of prioritizing process over outcomes, consensus over plurality, homogeneity over diversity, generality over specificity, stability over flexibility, precedent over evidence, governments over nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), ministries of foreign affairs over ministries of health, and lawyers over health professionals. International treaties are often vague on specific commitments, slow to be implemented, hard to enforce, and difficult to update. They can constrain future decision-making and crowd out alternative approaches.19 Confusing patchworks of issue-specific treaties may also deepen rather than contribute to solving challenges in global governance for health. Alternative international commitment mechanisms may achieve greater impact because countries are often willing to assume more ambitious obligations faster if the agreement does not clearly and perpetually bind them (Figure 1).17,20

FIGURE 1—

Strategic balance between treaties’ strength of commitment and depth of content.

Note. International treaties’ high strength of commitment may diminish their depth of content. The expected impact of any international agreement depends on both the content provisions it contains and the strength in which they are imposed on or enforced in countries that adopted it. Although not always true, the strength of an agreement’s commitment is often inversely proportional to the depth of its content. Enacting international treaties is the strongest way countries can communicate their intent to behave in a certain way. Countries may be willing to include more ambitious content in agreements like political declarations or codes of practice that do not commit them as forcefully.16

RISKS OF COERCION AND PATERNALISM

Proponents of international treaties often envision a future with higher minimal standards and new forms of accountability, which are both supported by NGO advocacy and litigation. International treaties that impose domestic obligations may have coercive and paternalistic effects for 3 reasons.

First, the terms of standard-setting international treaties are largely dictated by powerful countries on the basis of minimal expectations that they already meet, so new domestic standards often affect only poorer countries or countries with less governmental capacity. One prominent example is the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which obliges countries to regulate expression (i.e., copyright), indicators of source (i.e., trademarks), and practical inventions (i.e., patents) in ways that may disadvantage their economic development or diverge from historic cultural norms. Because of resource and technical limitations, this legally obliges poor countries to implement these “enlightened” policies—often instead of local priorities—even if they have no effect on other countries, cost more, and potentially achieve far fewer benefits than do local alternatives. Promised financial support from wealthy countries for implementing these policies is often not delivered, and poor countries usually cannot take full advantage of flexibilities or withdraw from international treaties without financial, security, or reputational consequences.16

Second, what on the surface may appear to be “voluntary” ratification of treaties may actually be something else and may be far from how legal systems in democratic countries would define this word. Involuntariness may result from incapacity (e.g., ratifying countries not having the technical expertise to fully assess the consequences of proposed treaties), lack of consent (e.g., despotic leaders ratifying treaties for their own benefit without the support of their citizens), corruption (e.g., negotiating agents being influenced to act against their countries’ interests), duress (e.g., credible threats of disproportionate consequences forcing countries to ratify treaties out of fear), and desperation (e.g., tragic circumstances encouraging countries to accept unconscionable terms in exchange for short-term assistance).

Third, pressure and litigation from foreign NGOs forcing compliance with “international standards” can be unhelpful foreign interference in domestic policymaking and priority-setting processes, especially considering how many NGOs are funded by organizations based in rich countries, to whom they are legally accountable rather than the people they intend to serve.21 Most NGOs make important contributions, but some are “a mirage that obscures the interests of powerful states, national elites and private capital.”22 This would especially include those NGOs set up by industry to lobby for unhealthy policies, like the US National Rifle Association (which calls itself “America’s longest-standing civil rights organization” and advocates fewer gun controls internationally),23 the International Chrysotile Association (which promotes asbestos’s “environmental occupational health safe and responsible use”),24 and the International Tobacco Growers’ Association (which aims “to ensure the long-term security of tobacco markets”).25 But this could also include those well-meaning foreign NGOs that succeed in getting their preferred interventions financed (e.g., high-tech hospitals in capital cities) at the expense of more cost-effective solutions (e.g., primary school education for girls).26

TRADE-OFFS AND CHOICES

Limited resources mean governance unavoidably involves complicated trade-offs and difficult social choices. Competing demands force governments to prioritize, which converts every budgetary or regulatory decision into an expression of local values, ethics, and priorities.27 Because all international treaties have domestic costs that must be budgeted, they cannot be considered undeniable demands but rather competing claims on limited national public resources. This dependence on public resources, in turn, entitles people to democratic accountability and distributive justice regarding the international treaties they choose to implement, which necessarily subjects them to political contestation. Although basic human rights and some other ground rules should be protected from such bargaining, prioritizing compliance with new international treaties beyond usual priority-setting processes and trade-offs is not always justified.28

International law recognizes only a few peremptory jus cogens norms—genocide, human trafficking, slavery, torture, and wars of aggression—that are beyond state sovereignty and from which countries can never derogate no matter the circumstances.15 These promote the kind of ground rules that are justifiably beyond usual priority-setting processes and trade-offs. Other rules from proposed new international treaties are unlikely to all be at this level.

FOUR CRITERIA FOR NEW GLOBAL HEALTH TREATIES

Treaties are certainly prominent among the many important implementation mechanisms for international agreements,17 but because of their unproven benefits and significant costs, risks of harm, and trade-offs, an analytic framework is needed to guide global decision-makers, national governments, and civil society advocates in ex ante evaluating whether to pursue new ones. We have proposed 4 criteria, which, if met, can help decision-makers ensure that any new global health treaties they adopt have reasonable prospects of yielding net positive effects.

First, there should be a significant transnational dimension to the problem that proposed treaties are seeking to address, involving many countries, transcending national borders, and transferring risks of harm or benefit across countries. Transnationality often involves interconnectedness (i.e., countries affecting one another) and interdependence (i.e., countries dependent on one another). Pandemics are an example, along with trade in health products, R&D for new health technologies, and international migration of health professionals. In these examples, effects of the problem or benefits of the solution cannot or should not be limited to their countries of origin. Problems that are contained within individual countries, or problems that can be stopped at national borders, do not meet this criterion.

Second, the goal and expected benefits should justify the coercive nature of treaties. For example, the proposed global health treaty could address multilateral challenges that cannot practically be resolved by any single country acting alone (e.g., tobacco smuggling, which is regulated by the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control). Alternatively, perhaps it helps overcome collective action problems in which benefits are accrued only if multiple countries coordinate their responses (e.g., pandemic outbreaks, which are governed by the International Health Regulations). This could include addressing the underprovision of public goods (e.g., health R&D) or overuse of common goods (e.g., antimicrobial medications). A proposed global health treaty may also justify its coercive nature if it advances superordinate norms that embody humanity and reflect near-universal values (e.g., basic human rights, including freedom from torture).

Third, international treaties should have a reasonable chance of achieving benefits through facilitating positive change. This means taking a realist and realistic view of what different actors can and will do both domestically and internationally, whether by choice or as limited by regulations, resources, governmental capacity, or political constraints. This also means proposals for new treaties should probably mobilize the full range of incentives for those with power to act on them, institutions specifically designed to bring edicts into effect, and interest groups that advocate their implementation.1

Fourth, treaties should be the best commitment mechanism for addressing the challenge among the many feasible competing alternatives for implementing agreements, such as political declarations, contracts, and institutional reforms.17 The best available research evidence should indicate that a new international treaty would achieve greater benefit for its direct and indirect costs than would all other possible options. At the very least, treaties should not be strategically dominated by other available mechanisms for committing countries to each other, considering expected impact, financial costs, and political feasibility, meaning there should not be a less costly and more realistic mechanism that is expected to be equally effective. The use of global health treaties would also be inappropriate to dictate poor countries’ domestic policies and priorities from afar (see the box on this page).

Four Criteria for New Global Health Treaties

| 1. Nature of the problem: significant transnational dimension |

| Involves multiple countries, transcends national borders, and transfers risks of harm or benefit across countries |

| 2. Nature of the solution: coercive nature of treaties justified |

| Addresses multilateral challenges that cannot practically be addressed by any single country alone, resolves collective action problems when benefits are accrued only if multiple countries coordinate their responses, or advances superordinate norms that embody humanity and reflect near-universal values |

| 3. Nature of likely outcome: reasonable chance of achieving benefits |

| Incentivizes those with power to act, institutionalizes accountability mechanisms designed to bring rules into reality, and activates interest groups to advocate its full implementation |

| 4. Nature of implementation: best commitment mechanism |

| Projected to achieve greater benefit for its costs than competing alternative mechanisms for facilitating commitment to international agreements |

Assessing proposals for new treaties on the basis of these 4 criteria is an exercise of interdisciplinarity in action. Each relies on the conceptual tools, theories, and perspectives of a different field of study. Assessing the first criterion, transnationality, depends on knowledge of political science and governmental capacity to stop threats at national borders. Assessing whether the second criterion of justifying coercion is satisfied involves ethical and legal analysis of norms, virtues, intentions, and consequences. Both economics and epidemiology can help decision-makers evaluate the third and fourth criteria, namely, whether there is a reasonable chance of the proposed treaty achieving benefits and whether a treaty is actually the best commitment mechanism for achieving their particular goals.

If these 4 criteria are met, there may be comparative advantages for using treaties to address global health challenges, as its supporters have long claimed. Treaties are the most powerful expression of countries’ intent to behave in a certain way, they are rhetorically powerful for encouraging compliance with commitments, and they build on an established (albeit contested) international system of principles, rules, and adjudicative procedures.28 The intense process of international treaty-making itself can have profound impacts through coalition building, norm setting, and fostering consensus that may emerge during negotiations.29,30 These qualities may be particularly important for high stakes and highly divisive issues of transnational significance. But if these 4 criteria are not met, alternative instruments may be more appropriate, because the costs, risks of harm, and trade-offs are probably not worth the benefits.

APPLICATION TO PROPOSALS FOR NEW TREATIES

Applying this analytic framework to 9 recent calls for new global health treaties reveals that none fully meet the 4 criteria. In most cases, this is because the goals and expected benefits did not justify the coercive nature of treaties and because competing options for commitment mechanisms may be more appropriate (Table 3).

TABLE 3—

Applying the Criteria to Proposals for New Global Health Treaties

| Proposal | Goal | 1. Nature of the Problem: Transnational, Yes or No | 2. Nature of the Solution: Justifies Coercion, Yes or No | 3. Nature of Likely Outcome: Net Benefits, Yes or No | 4. Nature of Implementation: Best Mechanism, Yes or No | Meet criteria? |

| Recent calls | ||||||

| 1. Framework Convention on Alcohol Control2 | Encourage action on unhealthy alcohol consumption | No: Except illicit trade, mostly requires domestic action | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| 2. Treaty on the Treatment of Elder Individuals3 | Promote healthy and dignified aging as a human right | No: Except illicit trade, mostly requires domestic action | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| 3. Falsified/substandard Medicines Treaty4 | Thwart trade of substandard drugs and promote medicine quality | Yes: Rampant illicit cross-border trade requires global action | Maybe: Problem may be unresolvable by any single country alone | Yes: Incentives and accountability mechanisms likelyb | Maybe: Related regimes of trade, intellectual property, drugs are highly legalized | Maybe |

| 4. Framework for Mandatory Impact Evaluations5 | Require impact evaluations of public policies | No: Evaluation mostly requires domestic action | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| 5. Convention on Non-Communicable Diseases6 | Encourage action on noncommunicable disease risk factors | No: Except illicit trade, mostly requires domestic action | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| 6. Global Nutrition Treaty7 | Promote better nutrition and combat malnutrition | No: Except illicit trade, mostly requires domestic action | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| 7. Framework Convention on Obesity Control8 | Encourage action on obesity risk factors (e.g., poor diet and insufficient exercise) | No: Except illicit trade, mostly requires domestic action | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| 8. Health Research and Development Treaty9 | Promote health research and development that addresses the needs of the world’s poor | Yes: Costs necessitate transnational financial burden sharing | Yes: Multilateral challenge and collective action problem | Maybe: Some incentives and perhaps some accountabilityb | Maybe: No evidence a treaty is best, but other tools have not delivered | Maybe |

| 9. Framework Convention on Global Health10 | Create framework of responsibilities on national and global health issues | Yes: Many dimensions of global health are transnational | No: Does not meet requirements justifying coerciona | No: Few incentives and likely weak accountabilityb | No: No evidence a treaty is better than alternatives | No |

| Additional proposal | ||||||

| Antimicrobial Resistance Treaty | Address the spread of resistant microbes and dearth of new antimicrobials | Yes: Risk spreads irrespective of national borders | Yes: Multilateral challenge and collective action problem | Yes: Incentives and accountability mechanisms likelyb | Yes: Regime is highly legalized and other tools have not delivered | Yes |

To justify coercion, proposed global health treaties should (1) address multilateral challenges that cannot practically be addressed by any single country alone, (2) resolve collective action problems in which benefits are accrued only if multiple countries coordinate their responses, or (3) advance superordinate norms that embody humanity and reflect near-universal values.

For a reasonable chance of achieving benefits, proposed global health treaties should incentivize those with power to act, institutionalize accountability mechanisms designed to bring rules into reality, or activate interest groups to advocate its full implementation.

According to this analysis, proposals for R&D and falsified/substandard medicines treaties may be the existing calls for new global health treaties that most closely meet these criteria. Securing R&D for health products needed in the least developed countries has proven to be a significant transnational challenge. This challenge involves a market failure that requires collective action among countries to address the underprovision of this global public good.31,32 However, whether a treaty is needed to achieve what other international commitment mechanisms have not is still uncertain and is heavily debated. If a treaty is indeed the best commitment mechanism for addressing this market failure, an R&D treaty would meet the 4 criteria.

Similarly, medicine quality is a cross-border challenge beyond the control of any single country. Up to 15% of all medicines globally may be substandard, dangerous, and fake, with the severity of this problem fundamentally rooted in and deepened by globalization.4 The challenge of falsified/substandard medicines also implicates several highly legalized regimes such as trade, intellectual property, fraud, organized crime, and narcotics, which perhaps—but not necessarily—make treaties the best international commitment mechanism for implementing agreements among countries in this domain.

Although these 9 recent calls for new global health treaties did not meet all 4 criteria, this does not mean it is impossible. Antimicrobial resistance may be the best candidate for an international treaty, at least compared with existing proposals. This problem is a multilateral challenge involving the overexploitation of a vital common-pool resource33–36 as well as a global public good challenge for ensuring the proper use of existing antimicrobials (which benefits all people well beyond the actual user) and continued progress in R&D toward new antimicrobials (which also benefits all).37–40 Antimicrobials can be used only so many times before bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi evolve, adapt, develop resistance, and render these medicines ineffective. So although it is in every person’s and every country’s rational interest to consume as much of these medicines as would be helpful to them, each use degrades the overall effectiveness of these medicines for everyone.

Further exacerbating this challenge is the structural misalignment between pharmaceutical companies’ market incentives to sell as many antimicrobial products as possible and the microbiological imperative of limiting use to prevent resistance. Inevitable competition from generic firms after the patent monopoly period—which is important for promoting access to medicines—further deepens these market dynamics and erodes any countervailing incentive to preserve antimicrobial effectiveness for the long term. The value of an antimicrobial resistance treaty, however, depends greatly on continued difficulties in developing new antimicrobials and countries’ ability to near universally adopt an international treaty containing sufficiently strong commitments and robust accountability mechanisms for resolving this challenge.

CONCLUSIONS

International treaties may in theory yield transformative benefits for global health, but they also carry high costs, risks of harm, and trade-offs. Calls for unjustified and unhelpful global health treaties diminish the possibility of worthy initiatives from being taken seriously. It is essential to determine when treaties should be used and when alternatives may be more appropriate. A commission on global health law could help identify such opportunities in ways that do not further complicate global governance architecture, including considering the role of the World Health Organization’s existing secretariat and governing bodies.2,15,41

Greater investments in empirically evaluating the range of international instruments and commitment mechanisms are also essential for learning which tools are best suited for addressing each global health challenge.42 For example, a robust impact evaluation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control could inform future decisions on potential treaties in other areas. In the meantime, unless proposals meet the 4 identified criteria, efforts aiming to better use or revise existing international instruments for global health purposes may be more productive for achieving health outcomes than for advocating new treaties.

Acknowledgments

S. J. Hoffman is financially supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Research Council of Norway, and the Trudeau Foundation.

We thank Emmanuel Guindon, Benjamin Mason Meier, Trygve Ottersen, Kevin Outterson, the peer reviewers, the journal editors, and the participants of seminars at Harvard University, Université de Montréal, University of Oxford, and the World Health Summit 2012 in Berlin for feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because data were obtained from secondary sources.

References

- 1.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Assessing the expected impact of global health treaties: evidence from 90 quantitative evaluations. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):26–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sridhar D. Health policy: regulate alcohol for global health. Nature. 2012;482(7385):302. doi: 10.1038/482302a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO, Garsia A. Governing for health as the world grows older: healthy lifespans in aging societies. Elder Law J. 2014;22(1):111–140. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fighting fake drugs: the role of WHO and pharma. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1626. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60656-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oxman AD, Bjørndal A, Becerra-Posada F et al. A framework for mandatory impact evaluation to ensure well informed public policy decisions. Lancet. 2010;375(9712):427–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gostin LO. Non-communicable disease: healthy living needs global governance. Nature. 2014;511(7508):147–149. doi: 10.1038/511147a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu S. Should we propose a global nutrition treaty? 2012. Available at: http://epianalysis.wordpress.com/2012/06/26/nutritiontreaty. Accessed January 6, 2014.

- 8.Urgently needed: a framework convention for obesity control. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61356-1. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dentico N, Ford N. The courage to change the rules: a proposal for an essential health R&D treaty. PLoS Med. 2005;2(2):e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gostin LO. Meeting basic survival needs of the world’s least healthy people: toward a framework convention on global health. Georgetown Law J. 2008;96(2):331–392. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flood CM, Lemmens T. Global health challenges and the role of law. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12001. doi:10.1111/jlme.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gostin LO. Global Health Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gostin LO, Sridhar D. Global health and the law. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1732–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1314094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy DT, Ellis JA, Mays D, Huang AT. Smoking-related deaths averted due to three years of policy progress. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(7):509–518. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Dark sides of the proposed Framework Convention on Global Health’s many virtues: a systematic review and critical analysis. Health Hum Rights. 2013;15(1):E117–E134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Alcohol control: be sparing with international laws. Nature. 2012;483(7389):275. doi: 10.1038/483275e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Assessing implementation mechanisms for an international agreement on research and development for health products. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):854–863. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. A framework convention on obesity control? Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2068. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy D. The international human rights movement: part of the problem? Harv Hum Rights J. 2002;15:101–126. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edge JS, Hoffman SJ. Empirical impact evaluation of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel in Australia, Canada, UK and USA. Global Health. 2013;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman SJ. Mitigating inequalities of influence among states in global decision making. Global Policy. 2012;3(4):421–432. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamat S. NGOs and the new democracy: the false saviours of international development. Harvard Int Rev. 2003;25(1):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Rifle Association. 2014. History: America’s longest-standing civil rights organization. Available at: http://home.nra.org/history. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 24.International Chrysotile Association. 2015. Available at: http://www.chrysotileassociation.com/en/about.php. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 25.International Tobacco Growers’ Association. Who we are and what we do. 2014. Available at: http://www.tobaccoleaf.org/conteudos/default.asp?ID=7&IDP=2&P=2. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 26.Copenhagen Consensus Center. 2008. Copenhagen consensus 2008—results. Available at: http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/sites/default/files/cc08_results_final_0.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 27.Holmes S, Sunstein CR. The Cost of Rights: Why Liberty Depends on Taxes. New York, NY: Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons BA. Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yach D, Bettcher D. Globalisation of tobacco industry influence and new global responses. Tob Control. 2000;9(2):206–216. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wipfli H, Huang G. Power of the process: evaluating the impact of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control negotiations. Health Policy. 2011;100(2–3):107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Research and development to meet health needs in developing countries: strengthening global financing and coordination. 2012. Available at: http://www.who.int/phi/CEWG_Report_5_April_2012.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2014.

- 32.World Health Organization. 2012. Sixty-fifth world health assembly. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/e/e_wha65.html. Accessed January 6, 2014.

- 33.Røttingen JA, Chamas C, Goyal LC, Harb H, Lagrada L, Mayosi BM. Securing the public good of health research and development for developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(5):398–400. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.105460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Røttingen JA, Chamas C. A new deal for global health R&D? The recommendations of the Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development (CEWG) PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostrom E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostrom E. Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am Econ Rev. 2010;100(3):641–672. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cars O, Högberg LD, Murray M et al. Meeting the challenge of antibiotic resistance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1438. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kesselheim AS, Outterson K. Improving antibiotic markets for long-term sustainability. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2011;11(1):101–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laxminarayan R, Heymann DL. Challenges of drug resistance in the developing world. BMJ. 2012;344:e1567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1567. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. Split WHO in two: strengthening political decision-making and securing independent scientific advice. Public Health. 2014;128(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman SJ. A science of global strategy. In: Frenk J, Hoffman SJ, editors. To Save Humanity From Hell: What Matters Most for a Healthy Future. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]