Abstract

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have demonstrated that measures of altered metabolism and axonal injury can be detected following traumatic brain injury. The aim of this study was to characterize and compare the distributions of altered image parameters obtained by these methods in subjects with a range of injury severity and to examine their relative sensitivity for diagnostic imaging in this group of subjects. DTI and volumetric magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging data were acquired in 40 subjects that had experienced a closed-head traumatic brain injury, with a median of 36 d post-injury. Voxel-based analyses were performed to examine differences of group mean values relative to normal controls, and to map significant alterations of image parameters in individual subjects. The between-group analysis revealed widespread alteration of tissue metabolites that was most strongly characterized by increased choline throughout the cerebrum and cerebellum, reaching as much as 40% increase from control values for the group with the worse cognitive assessment score. In contrast, the between-group comparison of DTI measures revealed only minor differences; however, the Z-score image analysis of individual subject DTI parameters revealed regions of altered values relative to controls throughout the major white matter tracts, but with considerable heterogeneity between subjects and with a smaller extent than the findings for altered metabolite measures. The findings of this study illustrate the complimentary nature of these neuroimaging methods.

Key words: : diffusion tensor imaging, MR spectroscopy, traumatic brain injury, Z-score image analysis

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) may result in direct tissue damage to the brain,1,2—including edema, hemorrhage, and contusion—that can be detected using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography. However, it is also accompanied by a complex series of pathological responses that result in a diffuse and widespread alteration of the cellular environment and metabolism2 that frequently is not detected using conventional structural neuroimaging methods,3 particularly for mild TBI. It is known that structural neuroimaging methods are insensitive to detection of the diffuse axonal injury (DAI) that is believed to underlie the cognitive and behavioral impact of the injury that can frequently occur following TBI. For this reason, there has been increasing interest in magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which can provide measures of altered pathophysiology and tissue metabolism to provide objective assessments of the degree of diffuse tissue injury.

Several MRS studies of TBI have demonstrated decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA), a marker of neuronal density and viability, and increased choline (Cho), a marker of membrane synthesis and gliosis that includes free choline, phosphorylcholine, and glycerophosphocholine, with changes detected in white matter and in regions remote from any MRI-observed lesions.4 While many studies used single-voxel measurements, Govind and colleagues5,6 used whole–brain magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) that revealed widespread metabolic alterations, which were primarily characterized by increased white matter Cho/NAA but also included changes in gray matter and increasing alteration with degree of injury. Using a two-dimensional MRSI measurement in supraventricular white matter, Gasparovic and colleagues7,8 reported an additional finding of increased signal from the combined peak of creatine (CRE) and phosphocreatine, suggesting an alteration of energy metabolism. While these previous reports demonstrate the sensitivity of MRS for detection of metabolic changes occurring as a result of mild head injury, the studies have presented analyses using between-group analyses of relatively large brain regions, and the relative vulnerability of specific brain regions in individual subjects to injury has not been investigated.

DTI maps the rate of diffusion of water molecules within the tissue as the mean diffusivity (MD) and the directionality of the diffusion through parameters such as the fractional anisotropy (FA). These measures reflect the cellular environment and have been shown to be sensitive indicators of edema and axonal injury that occurs as a result of TBI,9,10 with increased MD and decreased FA within the major white matter tracts. There is some variability in the reported findings that may be attributed in part to differences in the study procedures but it is apparent that there is heterogeneity in the distribution of the DTI-observed tissue injury and changes in these parameters over time.9,11

Many studies have evaluated DTI measures in specific regions across a group of TBI subjects; however, as discussed by Lipton and colleagues11,12 such analyses are limited by the considerable inter-subject variability of the injury. An alternative approach is to use individual-subject voxel-based analyses based on a quantitative comparison with normal control values following spatial registration of all images. This procedure was first used by Rutgers and colleagues13 for 21 subjects who had experienced a mild TBI with a wide range of time after injury (0.1 to 109 months). The researchers reported an average of nine small regions with reduced FA in each subject, widely distributed over the white matter. Similar findings have been reported in other studies, with multiple small regions of decreased FA and increased MD, and some areas of increased FA.11,14–16

The relative distributions of altered MRS and DTI measures have previously been reported for selected brain regions with a group of subjects with severe TBI,17 and results for single subjects have not been presented. In a study of 62 TBI subjects18 that examined DTI and MRS measures at 1 d and three months following a mild TBI, only significant increases of MD were found, with no significant changes of MRS measures observed using a region-of-interest analysis of two-dimensional MRSI data. The relative sensitivity of these two methods and the spatial distributions of the findings, therefore, warrant further study.

A general finding of these previous studies is that there is considerable variability of the mechanism of injury and in the distributions of the resultant tissue damage, although there are regions of the brain that are more vulnerable to injury. Additionally, despite widespread alterations of metabolism detected by MRS, the image-based DTI analyses indicate localized regions of injury. The aim of this study was to better define the extent and nature of findings obtained using DTI and MRSI in the same group of subjects with a range of degree of injury, and to examine if there are characteristic patterns of altered neuroimaging measures in these subjects. A secondary aim was to examine if there are differences in the relative distributions of these changes with the degree of injury, as indirectly indicated through measures of cognitive performance. For this purpose, whole–brain DTI and MRSI measurements were acquired that were both examined using similar voxel-based quantitative analysis methods.

Methods

Subject selection

Forty six subjects were consecutively recruited from the trauma center following a closed-head TBI. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Entry criteria included a loss of consciousness and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score on admission between 6 and 15. Additional requirements included the absence of a prior TBI event, psychiatric illness, or neurological disease, and the ability to take part in a MRI study and neuropsychological evaluation. Of these subjects, two withdrew and four were removed for reasons that included motion artifacts or missing data, leaving 40 subjects for analysis. Of this group, 23 had experienced a motor vehicle accident, six experienced an assault, four had been hit by a car, one experienced a fall, and six were struck by an object. In addition, 29 age-matched healthy control subjects were recruited.

Data acquisition methods

All subjects underwent a MRI study and completed a neuropsychological evaluation, which each took approximately 1 h. MRI data were acquired at 3 Tesla (Tim-Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using eight-channel phased-array detection. The protocol included a T1-weighted MRI with 1-mm isotropic resolution (magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence, echo time (TE)/ repetition time (TR)=4.43/2150 msec; 160 slices). Volumetric MRSI data were obtained using a spin-echo acquisition with selection of a 135 mm slab covering the cerebrum, Echo-Planar readout with 1000 spectral sample points and a spectral bandwidth of 1250 Hz, TR/TE=1710/70 msec, spatial sampling of 50×50×18 points over 280×280×180 mm3, and an acquisition time of 26 min.5 Data were processed in a fully-automated manner using the MIDAS package19 to provide metabolite images for NAA, Cre, Cho, and their ratios, with a 1 mL resultant voxel volume. Processing included signal normalization of individual metabolite images to institutional units using tissue water as a reference, and formation of tissue distribution maps at the SI resolution following segmentation of the T1-weighted MRI using FSL/FAST,20 which were used for correction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) partial volume in the analysis. All images were then spatially-registered and interpolated to 2 mm isotropic voxels. Additional details of the processing have been previously reported.21

DTI data were acquired using a diffusion weighted spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence with field of view=220×220×132 mm, TR=11,800 msec, TE=80 msec, parallel imaging factor 2, four averages, and 60 contiguous axial slices of thickness 2.2 mm, with an acquisition time of 10.8 min. Diffusion encoding used 12 directions with b=1000 sec/mm2, in addition to one set of images with no diffusion weighting. Maps of FA and MD were obtained using DTIStudio (www.mristudio.org) and spatially normalized using a large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping transformation22 to a template in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space with 1-mm isotropic voxels.

A battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to all subjects. Z-scores were calculated for each measure and composite scores were then derived for four cognitive domains important in TBI research. An overall composite score was then calculated for each subject based on the four domains. The cognitive domains and their associated subtests were: 1) attention (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [WAIS] Digit Span [Forward] and Trail Making Test A, and Wechsler Memory Scale [WMS] Faces I); 2) working memory (WAIS Digit Span [Backward]); 3) memory (WMS Faces II); and 4) executive function (WAIS Matrix Reasoning, Controlled Oral Word Association [either FAS or PTM for Spanish speakers], Animal Fluency, and Stroop Color Word Interference Test).

Data analysis

To examine differences in imaging measures as a function of the degree of injury the 40 TBI subjects were divided into two groups of 20 using the composite neuropsychological test score, based on the underlying assumption that a lower neuropsychological test score was related to a greater degree of overall injury.23 The group termed Group 1 contained subjects with the worse test scores and Group 2 contained subjects with the better test scores.

Three voxel-based analyses were performed using the MIDAS software package in order to determine the distributions of altered imaging measures with TBI, and the results displayed using MRICro (www.mricro.com). The following analyses were performed:

Group analysis

A voxel-based analysis of all maps was carried out to examine differences of group mean values for each TBI group and the control group using a Student's unpaired t-test. Following spatial normalization, the MRSI parameter maps were smoothed using a 10-mm full-width at half maximum Gaussian filter and the DTI maps were smoothed with a 6-mm Gaussian filter to minimize the influence of any errors in the registrations. Differences were considered significant for p<0.05, with correction for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate.24

For the MRSI analysis, voxels were excluded based on the following criteria: 1) line width >12 Hz; 2) having an outlying value greater than three times the standard deviation of all valid voxels over the image; 3) more than 30% CSF contribution to the voxel volume; and 4) fewer than 10 subjects that passed the previous exclusions. The individual metabolite maps were corrected for CSF partial-volume contribution. Maps of the percent difference relative to control values were generated showing only those voxels that reached significance and were contained within a cluster of greater than 100 voxels (0.8 mL).

For the DTI data, a brain mask that was comprised of white matter and deep gray matter regions was applied to exclude voxels outside of the brain or close to any CSF-containing regions, and voxels were retained only if they were part of a cluster of greater than 300 voxels (0.3 mL). This mask was created by segmentation of white matter in the standard space reference image followed by manual editing to include the additional gray matter structures while excluding a 2 mm region adjacent to the ventricles.

Individual subject Z-score analysis

For each subject a Z-score map was generated for each DTI and MRSI measure, using methods similar to previous implementations.11,13–16,21,25 This procedure maps at each voxel the difference of the individual subject maps from the control mean value, divided by the standard deviation from the control group. Differences were considered significant for p<0.05 with false discovery rate correction, and a thresholded Z-score map generated that showed only voxels that passed significance and cluster size requirements. For the MRSI analyses, the same voxel selection criteria as previously described were used and the analysis specifically accounted for the relative content of gray and white matter.21,26 For the MRSI analysis the control subject data were combined with an existing database21 to enable selection of age-matched control groups, for which age groups of 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, and 46–55 years old were used, with the number of subjects in each control group being 55, 52, 39, and 52 respectively.

Summed individual Z-score analysis

A map was generated for each DTI parameter from the sum of all voxels with significantly altered values, as indicated in the individual Z-score maps, across all subjects. These maps displayed a count of the number of subjects with significantly altered parameter values at each voxel, representing the frequency of DTI-detected tissue injury across each study group. This was done separately for positive and negative changes of the image parameter.

Results

The averaged neuropsychological testing Z-scores ranged from −1.61 to 0.43, and the mean values for study Groups 1 and 2 were −0.93 and −0.03, respectively. In Table 1 are shown the distribution of gender, age, and time after injury, GCS, and the average neuropsychological test scores for the study groups. Both groups included subjects with a range of GCS values. Group 1 had two subjects with GCS score ≤8, typically classified as severe injury, and 13 subjects with GCS score ≥13, which is classified as mild injury, and Group 2 had one subject with GCS of 6 and 18 subjects with GCS ≥13.

Table 1.

Number of Subjects and Ranges of Measures for Each of the Study Groups

| Number of subjects | Age | GCS | Days since injury | Average NP score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Total | Male | Female | Min | Ave. | Max | Min | Ave. | Max | Min | Median | Max | Min | Ave. | Max |

| TBI – All | 40 | 28 | 12 | 18.4 | 28.2 | 45.3 | 6 | 13.5 | 15 | 8 | 36.5 | 131 | −1.61 | −0.48 | 0.42 |

| Group 1 | 20 | 13 | 7 | 18.4 | 28.4 | 45.3 | 6 | 12.9 | 15 | 22 | 47 | 131 | −1.61 | −0.93 | −0.46 |

| Group 2 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 18.6 | 28.0 | 44.8 | 6 | 14.1 | 15 | 8 | 29.5 | 79 | −0.41 | −0.03 | 0.42 |

| Control | 29 | 11 | 18 | 18.1 | 31.8 | 52.8 | |||||||||

GSC, Glasgow Coma Scale; NP, neuropsychological test; Min, minimum; Ave., average; Max, maximum; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

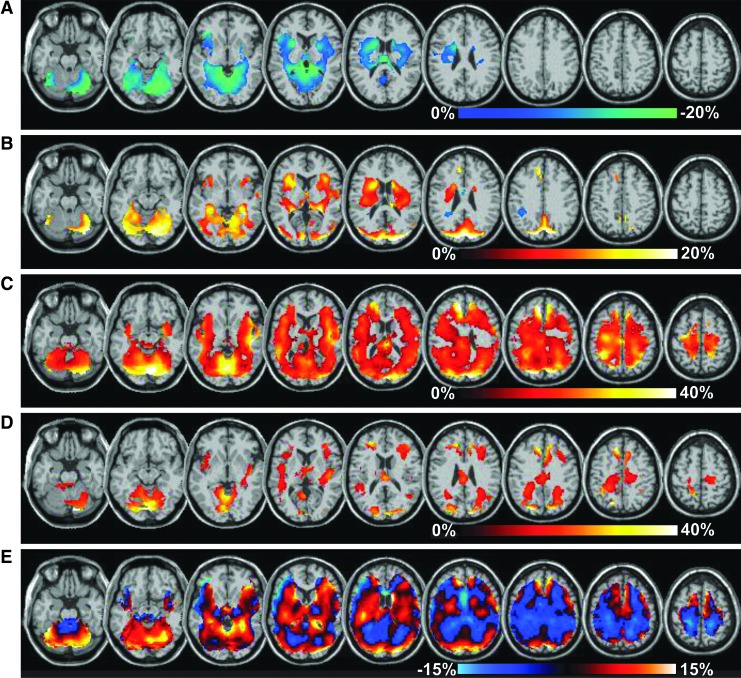

Significant between-group differences of all metabolites were observed for Group 1, which were widely distributed across the cerebrum and cerebellum, and results are shown in Figure 1. The strongest finding in terms of both the magnitude and extent of the differences was increased Cho and Cho/NAA, reaching as much as 40% increase from normal values; findings for Cho are shown in Figure 1C. The volumes of tissue corresponding to the significantly increased values of Cho shown in Figure 1 were 639 and 154 mL for Groups 1 and 2, respectively. Similarly, the volumes with increased Cho/NAA and Cre and decreased NAA/Cre were all larger for Group 1, indicating a larger tissue volume of altered metabolite values for the group with worse average cognitive measure.

FIG. 1.

Distributions of significant differences of the group mean metabolite measures relative to control values, shown as a color overlay superimposed on the spatial reference magnetic resonance imaging. Results for Group 1 are shown for N-acetylaspartate (NAA)/creatine (Cre; A), Cre (B), and choline (Cho; C), with the corresponding color scales indicated for each. The Cho map for Group 2 is shown in (D). In (E) is shown the Cre map without application of the threshold for significance, which shows regions of both increased and decreased values. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

While regions with significantly increased Cre were detected for the Group 1 evaluation (Fig. 1B), the images displayed without applying the threshold for significance, shown in Figure 1E, indicated that decreased values were also present that did not reach significance. Significant decreases of NAA were seen in a few small regions (data not shown), while the NAA/Cre map (Fig. 1A) showed larger regions with decreased values in temporal lobe and cerebellum. For Group 2, relatively few regions of altered metabolites were detected, with the most prominent result being increases of Cho, primarily located on the border between the gray- and white-matter and in the corpus callosum.

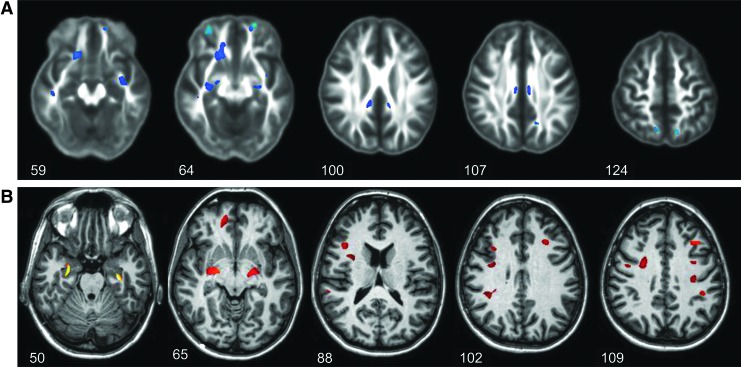

In Figure 2 are shown results for the between-group comparison of FA and MD maps for Group 1, with significant findings superimposed on the corresponding average value maps. Few regions indicated significant changes, with decreased FA and increased MD, and results are shown for only those slices where significant differences were found.

FIG. 2.

Distributions of significant differences of the mean diffusion tensor imaging measures for the mild traumatic brain injury Group 1, relative to control values. In (A) are shown results for fractional anisotropy (FA), with significant differences superimposed on the mean FA image from the control group, and in (B) are shown results for mean diffusivity. Data are shown for the slice numbers as indicated. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

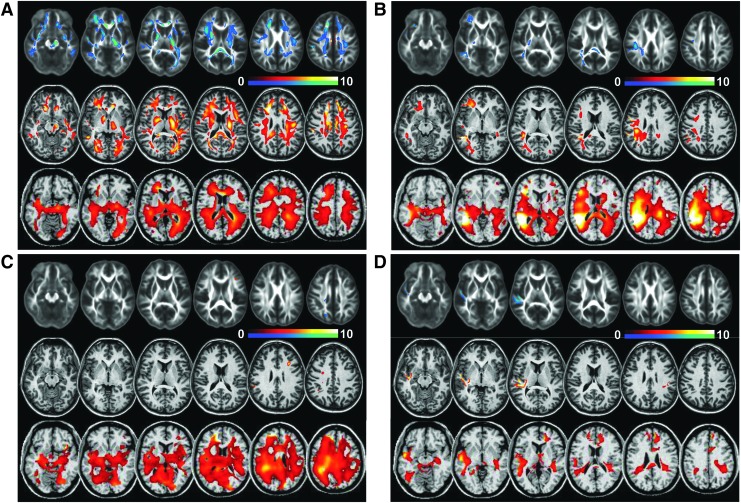

Example distributions of significant differences in individual subjects are shown in Figure 3 for FA, MD, and Cho/NAA. The maps show voxels identified as significantly different from control values with a color table ranging from z=−10 (green-blue) to z=10 (red-white), which are overlaid on the average control group FA map or the reference images used for the registrations. In Figure 3A are results for a subject with GCS 6, aged 18, studied 131 d after injury, and a relatively poor mean composite neuropsychological test score of -1.3. Widespread regions with decreased FA and increased MD and Cho/NAA are evident. MRI findings included multiple small hypointensities on gradient-echo T2 (not shown) in both frontal lobes, left parietal lobe (right side of the image), and splenium, indicative of DAI, with these same regions corresponding to greater changes seen on the FA and MD z-score maps.

FIG. 3.

Example individual subject Z-score maps for fractional anisotropy (top row), mean diffusivity (middle row), and choline/ N-acetylaspartate (bottom row). Voxels with significant differences are shown in the color overlay, with decreased values relative to control shown in blue-green, positive values shown in the red-white color scales, and with a maximum Z-score value of 10. Results correspond to subjects with GCS scores of (A) 6, (B) 12, (C) 14, and (D) 15, and additional subject information is provided in the text. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

In Figure 3B are results for a subject age 25 with GCS 12, 53 d after injury, and a mean composite neuropsychological test score of -0.83. MRI findings included encephalomalacia in the right temporal and parietal lobes, which correspond to the increased MD and Cho/NAA signal seen in this region. The metabolite changes were increased over a wider region than indicated from the DTI results, and included significantly decreased NAA and NAA/Cre in the right temporoparietal region that corresponds to the largest changes seen in the Cho/NAA Z-score maps.

In Figure 3C are results for a subject age 19, with GCS 14, 36 d after injury, and a mean composite neuropsychological test score of −1.06. MRI findings indicated multiple small hypointensities on T2*-weighted MRI in frontal, temporal, and right parietal white matter, which correspond to increased Cho/NAA levels. However, only small regions of altered DTI values are present. These findings suggest a diffuse axonal injury that corresponds to larger changes of Cho/NAA.

In Figure 3D are results for a subject age 36, with GCS 15, 19 d after injury, and a mean composite neuropsychological test score of 0.21, suggesting minimal cognitive impact of the injury. MRI findings included a right subdural hematoma and contusions in the right temporal and left parietal regions that correspond to regions of increased Cho/NAA, while increased Cho/NAA in the superior frontal did not correspond to any MRI findings. Altered DTI measures were localized to the contusion in the right temporal region, which also exhibited decreased NAA.

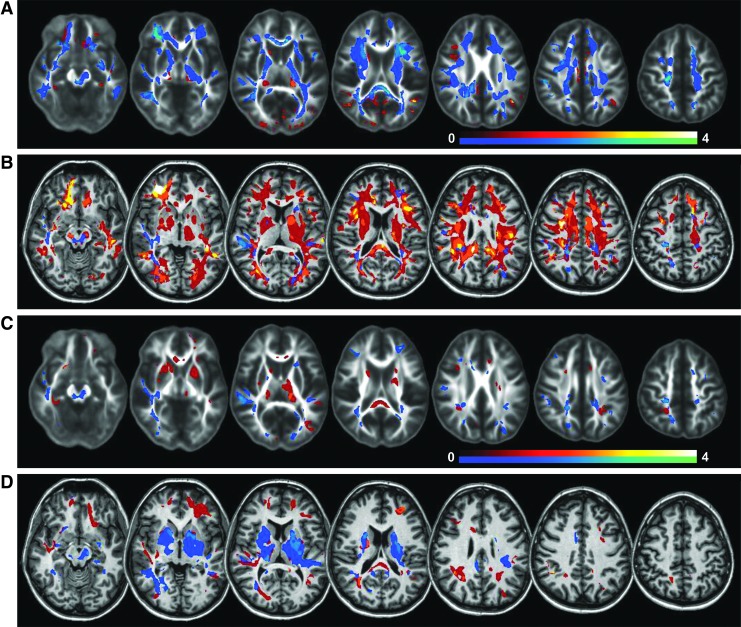

The results in Figure 3 indicate that altered DTI measures can be detected in several white matter tracts; however, this is primarily seen with more severe injury (Fig. 3A), while in the majority of subjects these changes are detected in only small regions with considerable variability in the locations between subjects. In order to better visualize the distribution and frequency of these changes, the sum of significantly altered voxels across all subjects (which depicts the relative frequency of altered FA and MD at each voxel) is shown in Figure 4. Results are shown for each TBI group using a scale for which the maximum values correspond to four subjects, or 20% of the subject group, with results for significantly increased parameter values shown using a red-white color scale and decreased values shown using the blue-green color scale. These maps indicate decreased FA and increased MD throughout the major white matter tracts for Group 1, though with small regions of increased FA values and decreased MD values, notably in the thalamus and putamen, which can be seen with both subject groups. However, it should be noted that the frequency of these changes at each location across the subject groups is low. The predominant regions exhibiting decreased FA and increased MD, with at least 20% of all subjects having altered values somewhere within a region, included the corpus callosum, which was most pronounced in the splenium, posterior thalamic radiation, the central portion of the fronto-occipital fasciculus, the internal capsule, and posterior corona radiata.

FIG. 4.

Voxel count maps indicating at each location the fraction of mild traumatic brain injury subjects having significantly altered fractional anisotropy FA (A and C) and mean diffusivity (B and D) values. Results are shown for Group 1 (A and B) and Group 2 (C and D). Voxels that showed an increase relative to control values are shown in the red-white color scale, and those with a decrease in value are shown in the blue-green color scale. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

Discussion

Using two types of image-based analyses, this study has demonstrated that both MRSI and DTI can detect widespread alteration of measured parameters following TBI, with both showing an increased extent of altered image parameters for subjects with worse cognitive performance.

The predominant MRS-observed measures of increased Cho and Cho/NAA were seen throughout the cerebrum and cerebellum, with large changes being observed for the mean values relative to control for a subject group with worse cognitive performance. These changes demonstrate widespread cellular injury, consistent with several previous studies4,5 at the time-point of a few weeks after injury and the presence of metabolic depression.27 While increased Cho also was seen in the group with better cognitive performance, this was much less widely distributed (Fig. 1D). This observation could explain the lack of changes of Cho in a group of 30 subjects with GCS≥13 reported by Yeo and colleagues8 that sampled a relatively small supraventricular region at mean time periods of 13 and 120 d post-injury. Additional findings included more localized decreases of NAA/Cre and increased Cre, although also with areas exhibiting a non-significant decrease of Cre. These spatially-variant alterations are consistent with differences in previous reports of Cre values.5,8 Reasons for the spatially-variant changes of Cre are not known but could reflect altered patterns of blood flow and energy metabolism. These differences in findings between previous studies illustrate an advantage of using the whole–brain MRS mapping approach for studies of TBI, which is characterized by considerable heterogeneity in the distributions of the injury.

This study found relatively few regions with altered DTI measures for the between-group voxel-based analysis (Fig. 2), which is in contrast to analyses based on region-of-interest measurements,9,10 as well as to a study of TBI subjects with persistent post-concussion symptoms that reported similar findings for voxel-based and ROI analyses.14 Since voxel-based analyses sample a smaller volume of tissue, this difference may reflect the larger inter-subject variability of DTI measures at the individual-voxel level and the variability across the subjects used for this study. Close inspection of the individual subject analyses indicates that even within anatomically-defined structures, there is heterogeneity of the altered DTI measures, which would also suggest that region-of-interest measurements may underestimate the degree of tissue damage.

The individual subject Z-score analyses of the DTI maps exhibited regions of reduced FA and increased MD in locations known to be susceptible to injury, similar to previous studies.11,14,16 For most subjects, these regions were small and widely scattered, with the exception of one subject with a more severe injury (Fig. 3A) that showed extensive changes. Lipton and colleagues11 have remarked on the unexpected presence of increased FA values, which also was seen in this study for approximately 12% of studies in the putamen and thalamus (Fig. 4). Since these regions are adjacent to the white matter tracts, it is hypothesized that this finding is caused by swelling of the larger axonal tracts due to cytotoxic edema leading to compression of the neighboring tissue and a reduction of extracellular space, a mechanism that also has been reported for hydrocephalus and adjacent to brain lesions.28,29 An additional cause of increased FA could be a reduced mean value in the control data caused by CSF partial volume contribution; however, the increased FA regions seen in this study are well separated from any CSF regions.

General observations of this study are that changes of both DTI and MRSI following TBI are widely distributed and predominately across white matter regions, with the metabolic changes covering a wider spatial extent than those seen in the DTI. It is also apparent that these changes reflect different aspects of the injury, since widespread metabolic changes can be observed in the absence of changes seen in the DTI measures (e.g., Fig. 3C).

Limitations of this study include that the DTI analysis did not account for age; however, the variation of both MD and FA for the age range of this study has been shown to be small and comparable to the variation across subjects,30, 31 and for the between-group comparisons there was no significant difference in the mean age for each subject group. Additionally, the separation of two subject groups based on neuropsychological evaluations remains an indirect index of injury severity that does not account for premorbid cognitive performance, and this therefore remains a possible factor in the difference imaging findings between the two subject groups.

Conclusion

Through the use of volumetric MRSI and DTI measurements in the same group of subjects following TBI and similar voxel-based analysis methods, this study has demonstrated the complimentary nature of findings from these two imaging methods. While both methods detect widespread and heterogeneous patterns of altered parameters, the MRS-observed increases of Cho and Cho/NAA were broadly distributed, indicating global metabolic alterations, whereas the detected changes of DTI measures are localized within the major white matter tracts and adjacent tissues.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health research grants R01NS055107 and R01EB000822. We thank Dr. Mori for making available resources to perform the DTI analysis and Clara Morales for assistance with the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gean A.D. and Fischbein N.J. (2010). Head trauma. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 20, 527–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigler E.D. and Maxwell W.L. (2012). Neuropathology of mild traumatic brain injury: relationship to neuroimaging findings. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 108–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H., Wintermark M., Gean A.D., Ghajar J., Manley G.T., and Mukherjee P. (2008). Focal lesions in acute mild traumatic brain injury and neurocognitive outcome: CT versus 3T MRI. J. Neurotrauma 25, 1049–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin A.P., Liao H.J., Merugumala S.K., Prabhu S.P., Meehan W.P., 3rd, and Ross B.D. (2012). Metabolic imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 208–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govind V., Gold S., Kaliannan K., Saigal G., Falcone S., Arheart K.L., Harris L., Jagid J., and Maudsley A.A. (2010). Whole-brain proton MR spectroscopic imaging of mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury and correlation with neuropsychological deficits. J. Neurotrauma 27, 483–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Govindaraju V., Gauger G., Manley G., Ebel A., Meeker M., and Maudsley A.A. (2004). Volumetric proton spectroscopic imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. A.J.N.R. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 25, 730–737 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasparovic C., Yeo R., Mannell M., Ling J., Elgie R., Phillips J., Doezema D., and Mayer A.R. (2009). Neurometabolite concentrations in gray and white matter in mild traumatic brain injury: an 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J. Neurotrauma 26, 1635–1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeo R.A., Gasparovic C., Merideth F., Ruhl D., Doezema D., and Mayer A.R. (2011). A longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 28, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shenton M.E., Hamoda H.M., Schneiderman J.S., Bouix S., Pasternak O., Rathi Y., Vu M.A., Purohit M.P., Helmer K., Koerte I., Lin A.P., Westin C.F., Kikinis R., Kubicki M., Stern R.A., and Zafonte R. (2012). A review of magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging findings in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 137–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hulkower M.B., Poliak D.B., Rosenbaum S.B., Zimmerman M.E., and Lipton M.L. (2013). A decade of DTI in traumatic brain injury: 10 Years and 100 articles later. A.J.N.R. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 34, 2064–2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipton M.L., Kim N., Park Y.K., Hulkower M.B., Gardin T.M., Shifteh K., Kim M., Zimmerman M.E., Lipton R.B., and Branch C.A. (2012). Robust detection of traumatic axonal injury in individual mild traumatic brain injury patients: intersubject variation, change over time and bidirectional changes in anisotropy. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 329–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum S.B. and Lipton M.L. (2012). Embracing chaos: the scope and importance of clinical and pathological heterogeneity in mTBI. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 255–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutgers D.R., Toulgoat F., Cazejust J., Fillard P., Lasjaunias P., and Ducreux D. (2008). White matter abnormalities in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. A.J.N.R. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 29, 514–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasahara K., Hashimoto K., Abo M., and Senoo A. (2012). Voxel- and atlas-based analysis of diffusion tensor imaging may reveal focal axonal injuries in mild traumatic brain injury - comparison with diffuse axonal injury. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 496–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipton M.L., Gellella E., Lo C., Gold T., Ardekani B.A., Shifteh K., Bello J.A., and Branch C.A. (2008). Multifocal white matter ultrastructural abnormalities in mild traumatic brain injury with cognitive disability: a voxel-wise analysis of diffusion tensor imaging. J. Neurotrauma 25, 1335–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim N., Branch C.A., Kim M., and Lipton M.L. (2013). Whole brain approaches for identification of microstructural abnormalities in individual patients: comparison of techniques applied to mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS One 8, e59382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tollard E., Galanaud D., Perlbarg V., Sanchez-Pena P., Le Fur, Y., Abdennour L., Cozzone P., Lehericy S., Chiras J., and Puybasset L. (2009). Experience of diffusion tensor imaging and 1H spectroscopy for outcome prediction in severe traumatic brain injury: Preliminary results. Crit. Care Med. 37, 1448–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayana P.A., Yu P., Hasan K.M., Wilde E.A., Levin H.S., Hunter J.V., Miller E.R., Patel V.K., S. , Robertson C.S., and McCarthy J.J. (2014). Multi-modal MRI of mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage Clin. 7, 87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maudsley A.A., Darkazanli A., Alger J.R., Hall L.O., Schuff N., Studholme C., Yu Y., Ebel A., Frew A., Goldgof D., Gu Y., Pagare R., Rousseau F., Sivasankaran K., Soher B.J., Weber P., Young K., and Zhu X. (2006). Comprehensive processing, display and analysis for in vivo MR spectroscopic imaging. N.M.R. Biomed. 19, 492–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Brady M., and Smith S. (2001). Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. I.E.E.E. Trans. Med. Imag. 20, 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maudsley A.A., Domenig C., Govind V., Darkazanli A., Studholme C., Arheart K., and Bloomer C. (2009). Mapping of brain metabolite distributions by volumetric proton MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 548–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oishi K., Faria A., Jiang H., Li X., Akhter K., Zhang J., Hsu J.T., Miller M.I., van Zijl P.C., Albert M., Lyketsos C.G., Woods R., Toga A.W., Pike G.B., Rosa-Neto P., Evans A., Mazziotta J., and Mori S. (2009). Atlas-based whole brain white matter analysis using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping: application to normal elderly and Alzheimer's disease participants. Neuroimage 46, 486–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraus M.F., Susmaras T., Caughlin B.P., Walker C.J., Sweeney J.A., and Little D.M. (2007). White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain 130, 2508–2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamini Y., Krieger A.M., and Yekutieli D. (2006). Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika 93, 491–507 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ling J.M., Pena A., Yeo R.A., Merideth F.L., Klimaj S., Gasparovic C., and Mayer A.R. (2012). Biomarkers of increased diffusion anisotropy in semi-acute mild traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal perspective. Brain 135, 1281–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maudsley A.A., Studholme C., and Govindaraju V. (2008). Tissue-dependent analysis of metabolic alterations in the brain by MR spectroscopic imaging. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Toronto, pps. 1604 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergsneider M., Hovda D.A., McArthur D.L., Etchepare M., Huang S.C., Sehati N., Satz P., Phelps M.E., and Becker D.P. (2001). Metabolic recovery following human traumatic brain injury based on FDG-PET: time course and relationship to neurological disability. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 16, 135–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assaf Y., Ben-Sira L., Constantini S., Chang L.C., and Beni-Adani L. (2006). Diffusion tensor imaging in hydrocephalus: initial experience. A.J.N.R. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 27, 1717–1724 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schonberg T., Pianka P., Hendler T., Pasternak O., and Assaf Y. (2006). Characterization of displaced white matter by brain tumors using combined DTI and fMRI. Neuroimage 30, 1100–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klimas A., Drzazga Z., Kluczewska E., and Hartel M. (2013). Regional ADC measurements during normal brain aging in the clinical range of b values: a DWI study. Clin. Imaging 37, 637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe M., Sakai O., Ozonoff A., Kussman S., and Jara H. (2013). Age-related apparent diffusion coefficient changes in the normal brain. Radiology 266, 575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]