Abstract

We sought the collaboration of an international airline and border control agencies to study the feasibility of entry screening to identify airline travelers at increased risk of influenza infection. Although extensive and lengthy negotiations were required, we successfully developed a multisector collaboration and demonstrated the logistical feasibility of our screening protocol. We also determined the staffing levels required for a larger study to estimate the prevalence of influenza in international airline travelers.

Entry screening of airline travelers is a potentially important intervention for preventing or delaying entry of pandemic influenza into a country. However, the feasibility, effectiveness, operational requirements, and likely success of screening questionnaires and airport testing in detection of influenza-infected travelers have not yet been established.1 Our pilot study of airline passengers entering New Zealand showed that such research can be conducted with a questionnaire and screening protocol to identify travelers at increased risk of seasonal influenza.

METHODS

Initial consultation with industry organizations, the airport company, and border control agencies was successful in gaining their support for our study, but our efforts to secure the participation of an airline were repeatedly unsuccessful until we obtained written support for the study and encouragement to airlines to participate from the New Zealand Ministry of Health. In June 2007, agreement was finally achieved, 7 months after initial contact.

We designed a screening questionnaire to identify travelers at increased risk of influenza infection. Information sought included self-report of symptoms, vaccination, travel and exposure history, and contact details for follow-up. A random sample of 30% of questionnaires were selected with the RAND function of Microsoft Excel 2004 version 11.3.3 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and marked prior to distribution.

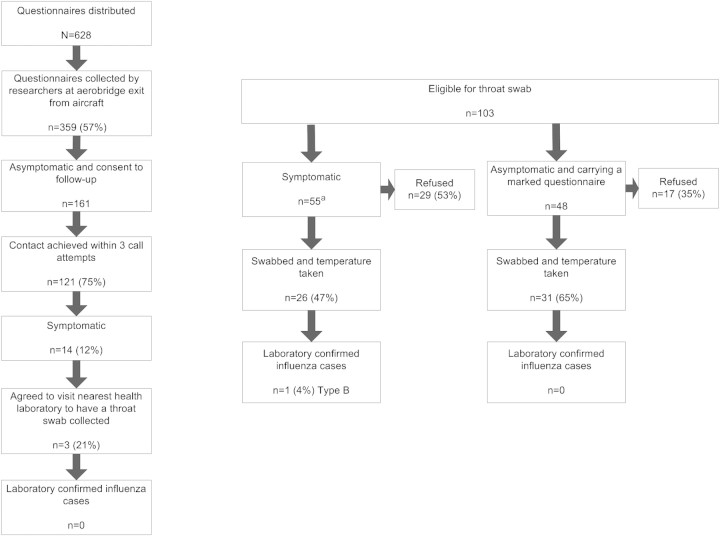

Figure 1 shows the in-flight and airport processes involved in the screening of travelers on 5 selected flights from Australia entering Christchurch International Airport in July and August 2007 (midwinter). Symptomatic travelers and those holding a marked questionnaire were requested to provide a throat swab sample.

FIGURE 1.

In-flight and airport study processes.

aEligible respondents were all those who reported at least 1 symptom (symptomatic) or, if asymptomatic, were holding a marked questionnaire.

Follow-up of all asymptomatic respondents who provided contact details was undertaken 3 days after their arrival, and those who reported having developed 1 or more symptoms were invited to provide a throat swab sample. Those who agreed were referred to their nearest diagnostic laboratory for a throat swab.

All throat swabs (airport and follow-up) were placed in viral transport medium and transported on ice to Canterbury Health Laboratories, Christchurch, for analysis by cell culture and real-time polymerase chain reaction (described elsewhere).2,3

RESULTS

The number of staff members required to collect questionnaires, identify respondents eligible for a throat swab, and escort them through immigration was larger than anticipated, primarily because of the speed at which travelers disembarked their aircraft and the time it took to escort respondents. Increasing staff numbers resulted in faster and more complete questionnaire collection and identification of eligible respondents.

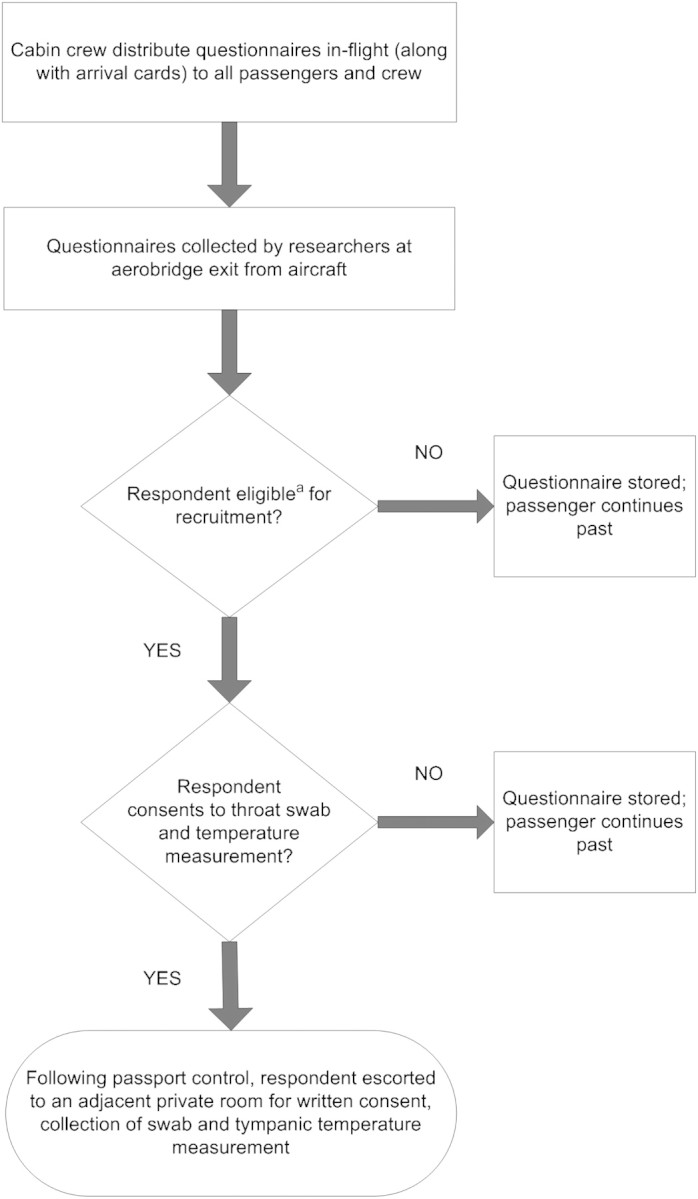

Figure 2 shows the recruitment and retention of respondents. No information was available on nonrespondents because passenger manifests were not made available to the research team.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment and retention of study participants.

Note. Three respondents (3/359; 0.8% of all respondents; 95% confidence interval = 0.2, 2.6) met the influenza-like illness case definition of fever or chills and cough or sore throat. aThis represents 15% (55/359) of all questionnaire respondents.

A single passenger was confirmed by the laboratory to have influenza (type B). This passenger reported only respiratory symptoms and no fever or chills.

DISCUSSION

Our pilot study showed that, with considerable effort, it is possible to collaborate with an airline, key airline industry organizations, and border control agencies to conduct research to support the design of a border screening protocol for detecting travelers at increased risk of influenza infection. Ultimately, successful airline engagement was facilitated by high-level support from the Ministry of Health and the momentum of the New Zealand government's intersectoral pandemic planning.

The absence of good evidence for the effectiveness of border screening and of data for predictive modeling and for planning for logistical requirements is reflected in the lack of detail in many countries’ pandemic plans about how such screening will be implemented.4,5 Despite our study's small size, it provided some useful information for those who must nonetheless plan for managing a possible pandemic. To our knowledge, our study was the first to gain airline approval to distribute a health questionnaire on board aircraft and the first designed to estimate influenza prevalence in airline travelers.

Locating screening at the point of aircraft disembarkation requires large numbers of staff; collecting questionnaires at, or immediately following, immigration would better control the flow of travelers, improve identification of symptomatic travelers for further investigation, and substantially reduce staffing requirements.

Voluntary questionnaire completion yielded a 57% response rate and a much higher proportion of people reporting symptoms than expected. In the event of a pandemic, health declarations could become mandatory, potentially reducing, but not eliminating, response bias. Issues such as the veracity of self-reporting, the proportion of infected travelers who are asymptomatic, the sensitivity of sample collection and analysis techniques, and location of people for follow-up would, however, remain.

Three-day follow-up required considerable resources and was unsuccessful in contacting 25% of those who had indicated a willingness to be contacted. Furthermore, few travelers were prepared to go to a laboratory to have a swab taken if they developed symptoms. This suggests that postentry follow-up of travelers might not be an effective way of managing the entry of a pandemic virus. Despite the logistic and cost implications, where there is concern that a person infected with a highly infectious novel influenza virus may be on board an aircraft, it may be necessary to quarantine all passengers on that flight until a definitive diagnosis can be made or excluded.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States (grant 1 U01 CI000445-01).

We thank Air New Zealand for allowing the use of their flights and Christchurch International Airport Limited, New Zealand Customs Service, and Community and Public Health for their cooperation and assistance. We are also grateful to Heath Kelly and Nick Wilson for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article and to Francisco Alvarado-Ramy, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for his input into the questionnaire design.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the New Zealand Health and Disability Multiregion Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Bell DM, World Health Organization Working Group on International and Community Transmission of SARS. Public health interventions and SARS spread, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(11):1900–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennings LC, Anderson TP, Beynon KA, et al. Incidence and characteristics of viral community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax. 2008;63:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennings LC, Anderson TP, Werno AM, Beynon KA, Murdoch DR. Viral etiology of acute respiratory tract infections in children presenting to hospital: role of polymerase chain reaction and demonstration of multiple infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(11):1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mounier-Jack S, Jas R, Coker R. Progress and shortcomings in European national strategic plans for pandemic influenza. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:923–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLeod M, Kelly H, Wilson N, Baker MG. Border control measures in the influenza pandemic plans of six South Pacific nations: a critical review. N Z Med J. 2008;121:62–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]