Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

Estrogen receptor alpha 36 (ERα36), a truncated variant of ERα, is located in cytoplasm and membrane that is different from other nuclear receptors of ERα family. ERα36 is involved in progression and treatment resistance of a variety of carcinomas. However, the clinical and prognostic significance of ERα36 in renal tumors have not been fully elucidated.

Here, renal tumor tissues from 125 patients were collected and immunohistochemical stained with ERα36 antibody. ERα36 expression level and location in these cases were analyzed for their correlations with clinical characteristics. The differential diagnosis value was also assessed for benign and malignant renal tumors, as well as its prognostic value.

The results showed that membrane ERα36 expression was rarely detected in benign tumors but predominantly observed in malignant renal tumors. Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that significant correlations of high ERα36 level and ERα36 membrane expression were correlated with both poor disease-free survival and overall survival. Univariate and multivariate analysis confirmed that both ERα36 high expression and membrane location can serve as unfavorable prognostic indicators for renal cell carcinoma.

It is thus concluded that membrane ERα36 expression is valuable for differential diagnosis of malignant renal tumors from benign ones. Both ERα36 high expression and membrane location indicate poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma.

INTRODUCTION

Most primary renal tumors are malignant, but it is difficult for a differential diagnosis of benign renal tumors from malignant ones, because of the complicated histological characters in renal tumors.1,2 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the leading lethal urologic malignancy, which accounts for about 3% of malignant neoplasm.3 The common therapy for RCC is surgery, followed by chemotherapy or radiotherapy.4 However, high recurrence rate (20%–40%) is observed during these treatments.5 Local recurrence or distant metastasis usually leads to incurable disease of localized RCC. The lack of biomarkers for prognosis estimation may lead to poor clinical response.4,6 Hence, it is required to investigate the predictive biomarkers for differential diagnosis and targeting therapies for renal tumors.

Emerging proofs indicate that estrogens and their receptors play critical roles in various cancers and it is speculated that human kidney maybe also affected.7 The animal models of renal cancer that were established with estrogens exposure also confirmed that hormone/estrogen receptor (ER) complex participated in renal cell carcinoma initiation and progression.8–10 Two types of ERs, ERα and ERβ were investigated in clinical cases in previous studies.11–14 However, immunohistochemistry (IHC) study of tissue microarray (TMA) showed that ERα immunoreactivity was less than 10% of tumor cell nuclei.15,16 Another study found that estrogen-activated ERβ acted as a tumor suppressor in renal cell carcinoma.12 However, gene expression analysis of ER targeted genes in renal cell carcinoma demonstrated that ER signaling was closely associated with tumor progression.17,18 Therefore, hormone/ER signaling-related cancer progression is probably mediated by another ER variant.

ERα36 is a truncated variant of ERα, which was reported located in membrane and cytoplasm, rather than nuclei.19 It is participated in non-genomic estrogen signaling to promote cell proliferation.20,21 The expression of ERα36 is correlated poor prognosis in many kinds of carcinoma.22–24 In this study, we assessed the expression of ERα36 by IHC in renal tumors, and its association with clinicopathologic characteristics as well as clinical outcome. We further evaluated its differentiation and prognostic significance in renal tumors.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients and Tumor Tissues

The retrospective study cohort consisted of 125 patients with primary renal tumors, who underwent surgical resection in the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University Medical College, and 401st Hospital, Shandong, China, between 2001 and 2013. Informed consent was obtained from each patient according to the research proposals approved by the local ethics committee of Qingdao University and 401st Hospital. Eligibility criteria included written informed consent and availability of tumor tissue, and follow-up data. For each patient, the following clinicopathologic information was collected, including age, sex, tumor size, TNM stage, presence of histological tumor necrosis, and Fuhrman grade. Clinical information was obtained by reviewing the medical records, by telephone or written correspondence, and by reviewing the death certificate. Follow-up information was updated every 6 months by telephone interview or questionnaire letters and was last done in January 2015.

TMA and IHC

The IHC study was performed as previously described.24 ERα36 expression levels in 5 renal tumor tissues were studied by immunoblotting and qRT-PCR assays,19 which confirmed the IHC staining specificity (Supplemental Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/MD/A310). TMA was created from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of the patients. All samples were reviewed histologically by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, and representative areas were marked on the paraffin blocks away from necrotic and hemorrhagic materials. Sections from the TMA blocks were cut at 4 μm. Primary antibody against human ERα36 (Shinogen, China) was applied for immunohistochemistry analysis. Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer pH 6.0, then the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody at 1:200. Next, they were rinsed with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and incubated with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, followed by a rinse in PBS, incubation with diaminobenzidine staining, and counterstaining with hematoxylin blue. The negative control sections were incubated with control IgG in equal concentrations to the primary antibody, and known positive human breast cancer tissue was performed as positive control.

Evaluation of ERα36 Immunohistochemical Staining

Representative IHC images in renal cell carcinoma tissues were collected at 40× objective with BX51 microscope (Olympus, Japan) and DP72 Camera (Olympus, Japan). The IHC staining level was assessed with German semiquantitative scoring system.25 The score for each sample was multiplied the staining intensity (0, no staining; 1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong) and the percentage of tumor cells (0, 0%; 1, 1%–24%; 2, 25%–49%; 3, 50%–74%; 4, 75%–100%) at each intensity level, ranging from 0 (the minimum score) to 12 (the maximum score). The membrane/cytoplasm positive staining was determined by the subcellular location of the ERα36 positive granules. Generally, ERα36 positive granules, which arranged as cellular outlines, were diagnosed as membrane positive, whereas those with brown intracytoplasmic granules were diagnosed as cytoplasm positive. The IHC results were evaluated by 2 pathologists without the knowledge of patient outcome.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 software. The categorization was analyzed with the receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROC).26 The correlation of ERα36 and other potential clinical variables were assessed using Fisher exact test.27,28 Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test was applied to compare survival curves.29 A univariate/ multivariate analysis was done using Cox proportional hazards model. Hazard ratios and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were computed to provide quantitative information about the relevance of results of statistical analysis.30 All statistical tests were 2 sided and differences with a P value of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Associations with ERα36 Expression

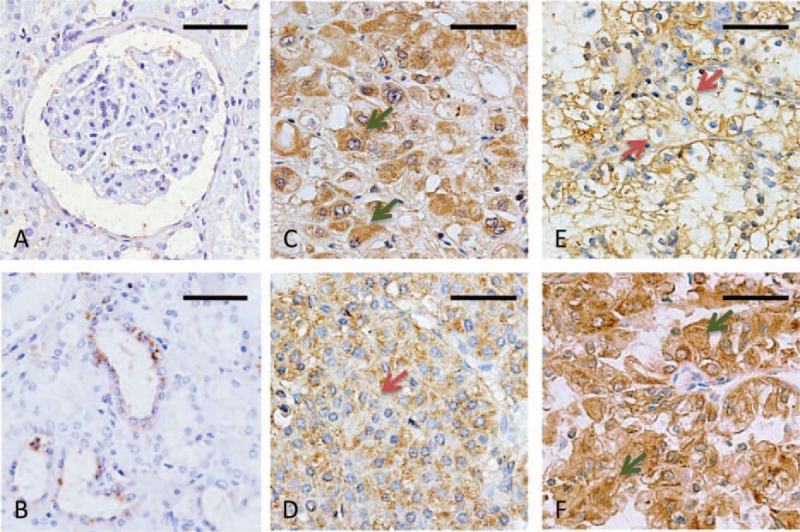

A total of 99 patients with renal cell carcinoma were analyzed for ERα36 expression, as well as another 26 cases of diagnosed benign renal tumor. Immunohistochemical staining showed that the pericarcinous renal tissues were observed with low ERα36 immunoreactivity. ERα36 expression was rarely observed in nephron (Figure 1A), but found in some renal tubules (Figure 1B). However, ERα36 expression was found in benign renal tumors (Figure 1C, D). High ERα36 expression was also observed in primary renal cell carcinoma, which was predominantly located in the cytoplasm and membrane of cancer cells (Figure 1E, F). In the cancer cell bulks, ERα36 expression was distributed primarily in a hierarchical pattern (Figure 1F).

FIGURE 1.

ERα36 expression in renal tumors (immunohistochemistry). (A, B) Low immunoreactivity was observed in the pericarcinous renal tissues: nephron (A) and renal tubules (B). (C, D) Most benign renal tumors showed dominant cytoplasm ERα36 expression (C). Only 1 case showed weak membrane location (D). (E, F) ERα36 positive staining was observed in the membrane (E) or cytoplasm (F) of renal cell carcinomas. Representative tumor cells positive for cytoplasm or membrane were shown with arrows (green arrows, cytoplasm; red arrows, membrane). Scale bar = 50 μm. ERα36 = estrogen receptor alpha 36.

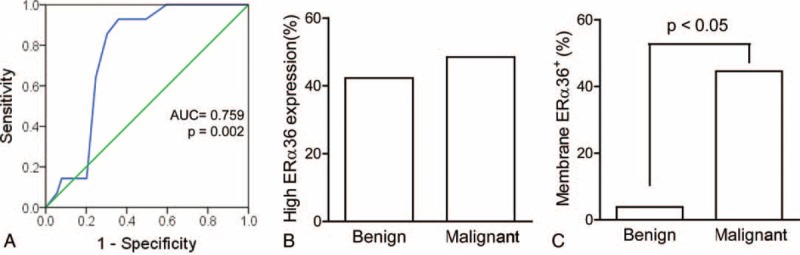

Comparison of ERα36 Expression in Benign and Malignant Renal Tumors

To determine the differential diagnosis value of ERα36 in renal tumors, a comparison was performed between renal cell carcinoma and benign tumors. The primary tumors were categorized into 2 groups according to the IHC scores: high (score ≥5); low (score ≤4) (Figure 2A). No significant difference in the percentage of ERα36high cases was observed between malignant and benign tumors (48.5% vs 42.3%, Figure 2B). Of interest, a remarkable difference was observed in ERα36 location between benign and malignant tumors. Membrane location of ERα36 was rarely observed in benign tumors rather than malignant ones (3.5% vs 46.5%, Figure 2C). ERα36 expression in benign tumors was characteristically located in the cytoplasm (Figure 1C), only 1 benign tumor showed weak membrane positive staining (Figure 1D), whereas higher percentage of membrane positive was observed in malignant ones (Figure 1E). Thus, ERα36 expression location may be served as a differential diagnosis marker for renal tumors.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of ERα36 expression in benign and malignant renal tumors. (A) A receiver-operating characteristic curve was analyzed for a reasonable cutoff point, which support the cutoff point, was score = 4.5 (low: score ≤4; high: score ≥5). The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.759 (P = 0.002). (B) Percentage of ERα36high in benign and malignant renal tumors. (C) Percentage of membrane ERα36 expression in benign and malignant renal tumors. Data were analyzed with χ2 test. ERα36 = estrogen receptor alpha 36.

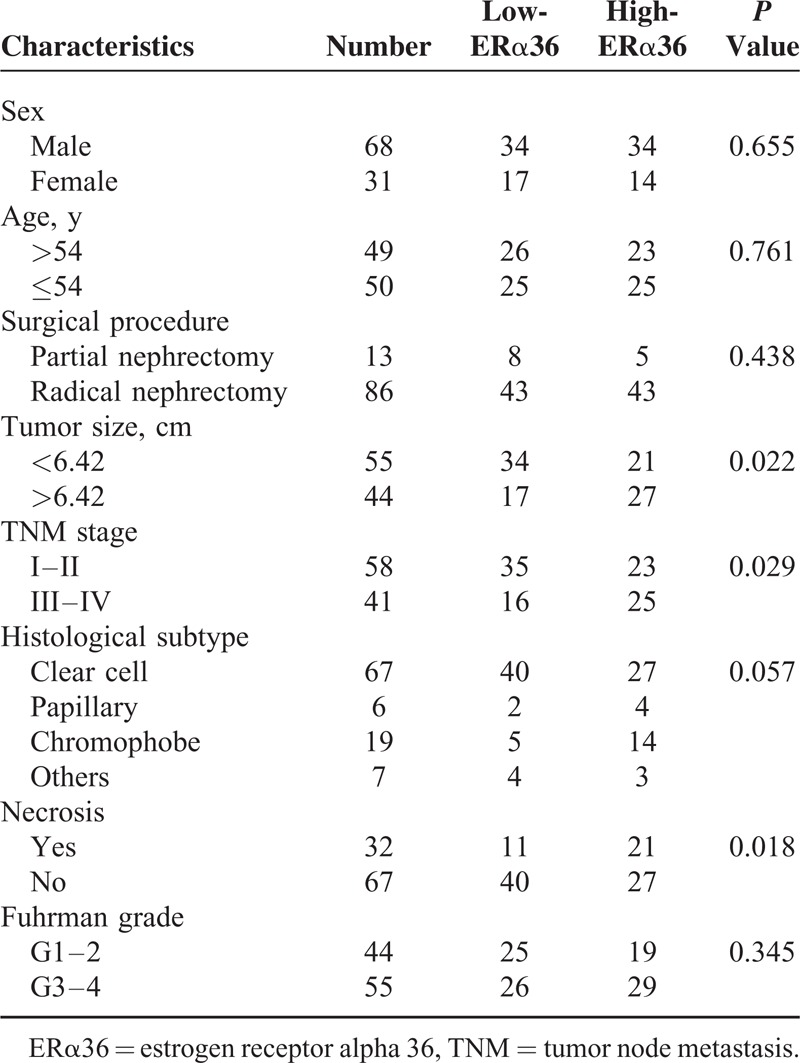

Relationship Between ERα36 Expression and Clinical Features

The relationships between ERα36 expression levels and clinical features in renal cell carcinoma were listed in Table 1. Totally 48 cases were observed with high ERα36 expression. ERα36 expression level was statistically associated with tumor size (P = 0.022), clinical stage (P = 0.029), and necrosis (P = 0.018). ERα36 high expression was correlated with larger tumor size, late clinical stage and more necrosis in tumor tissue. However, we failed to detect significant correlations between ERα36 expression level and other clinical characteristics, including age, sex, resection procedure, histological subtype, and Fuhrman grade.

TABLE 1.

Correlations of ERα36 Expression Level and Clinical Characteristics of Renal Cell Carcinoma

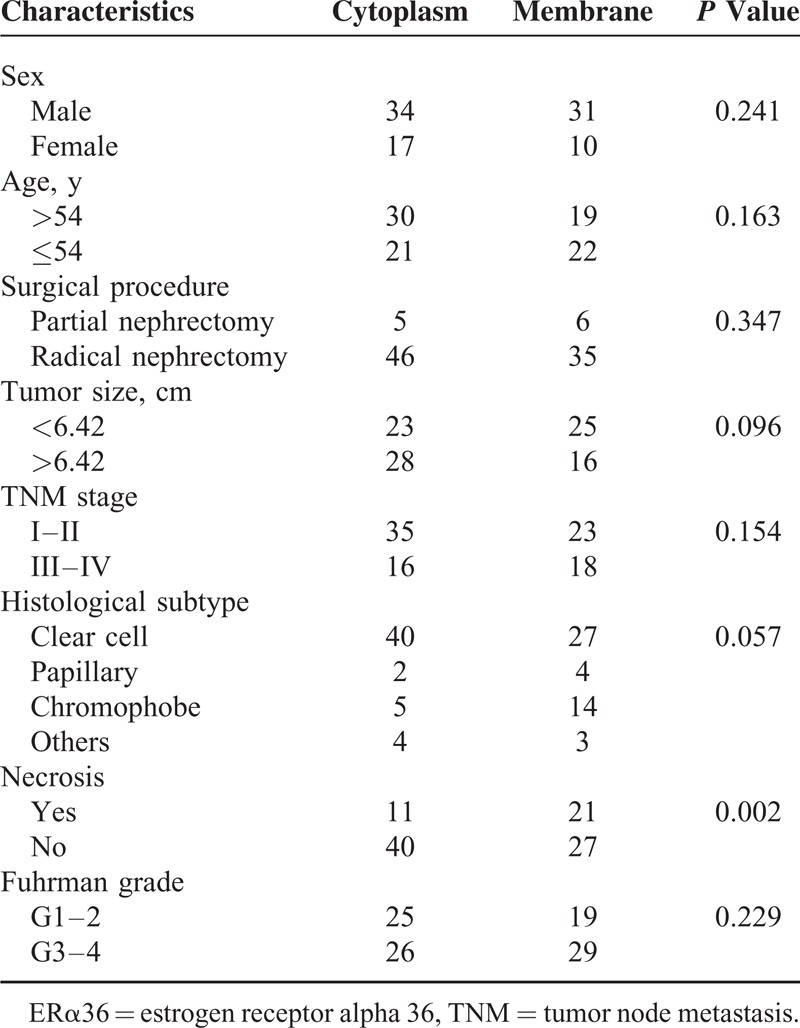

Furthermore, the relationships between ERα36 location and clinical features were shown in Table 2. Dominant membrane ERα36 expression was found in 41 cases, and cytoplasm expression in 51 cases (7 cases which scored 0 were excluded). Different location of ERα36 was only correlated with necrosis (P = 0.002). More necrosis was observed in membrane ERα36 expression cases. No significant correlation was found between ERα36 location and other clinical characteristics. Moreover, no significant correlation was observed between ERα36 expression level or subcellular location and ERα66 expression (Supplemental Figure 2, http://links.lww.com/MD/A310, and Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/MD/A310).

TABLE 2.

Correlations of ERα36 Location and Clinical Characteristics

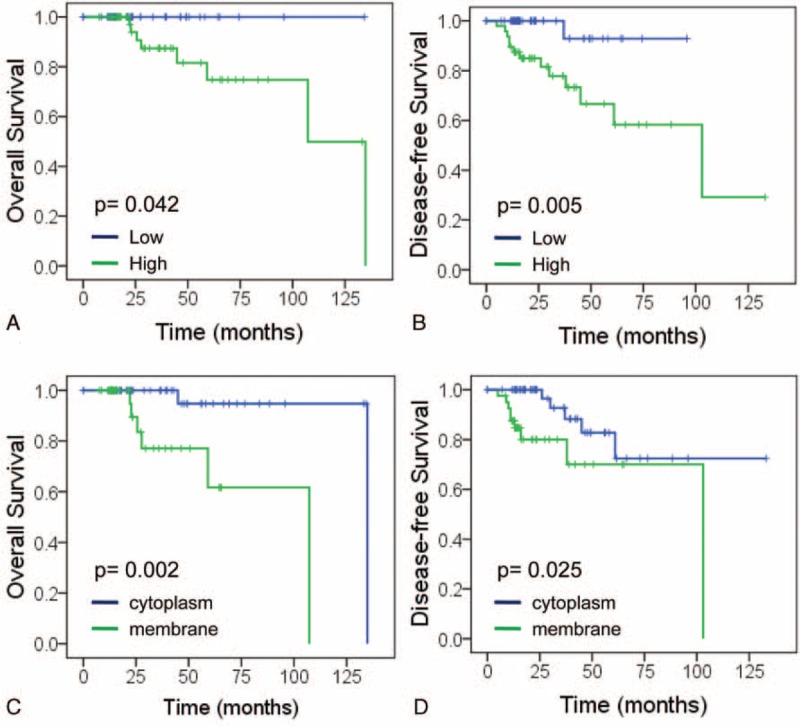

ERα36 Expression Correlated With Poor Clinical Outcome

Follow-up information was available for all patients and the median period was 40.9 months (range: 21–135 months). During the follow-up period, carcinoma progression was found in 14 patients (14.1%). Kaplan–Meier curves were analyzed to show that ERα36 high expression was statistically correlated with both poor overall survival (OS, P = 0.042) and disease-free survival (DFS, P = 0.005) in renal cell carcinoma (Figure 3A, B). More importantly, worse prognosis was also observed in the patients with ERα36 membrane expression than those predominately in cytoplasm in both OS (P = 0.002) and DFS (P = 0.025) (Figure 3C, D).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of ERα36 expression on patient prognosis. (A, B) High ERα36 expression is associated with poor prognosis of patients: overall survival (A) and disease-free survival (B). (C, D) Membrane ERα36 expression is associated with poor prognosis of patients: overall survival (C) and disease-free survival (D). ERα36 = estrogen receptor alpha 36.

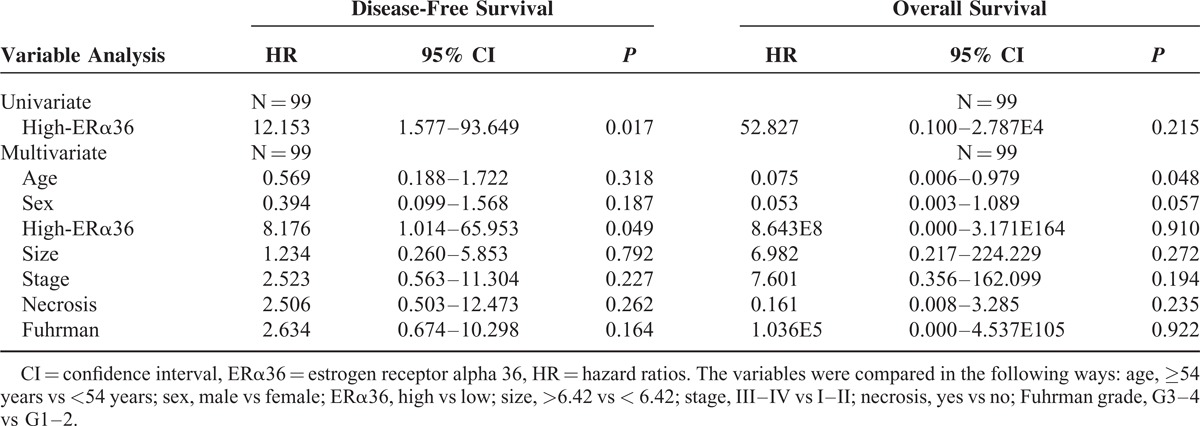

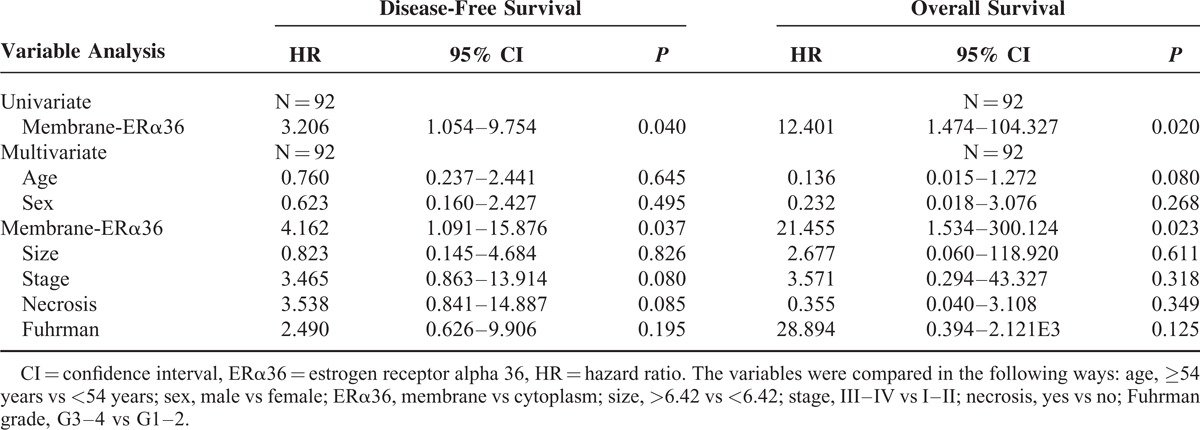

Prognostic Significance of ERα36 Expression

Cox univariable and multivariable proportional hazard models were constructed to evaluate the independent prognostic significance of ERα36 expression levels and locations with clinical characteristics including age, sex, tumor size, clinical stage, tumor necrosis, and Fuhrman grade. The results of Cox univariate analysis showed that ERα36 high expression was a significant predictor for shorter DFS in renal cell carcinoma, independent of other factors (P = 0.017, Table 3). Moreover, the membrane ERα36 expression was also a significant predictor for both shorter DFS and OS (P = 0.040, P = 0.020, Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Disease-Free Survival and Overall Survival (ERα36 Expression Level)

TABLE 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Disease-Free Survival and Overall Survival (ERα36 Membrane Location)

Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that ERα36 high expression was significantly correlated with worse DFS (P = 0.049, Table 3), but not correlated with OS (P = 0.910, Table 3). More importantly, significant worse DFS and OS were observed in the patients with ERα36 membrane positive patients relative to the cytoplasm positive ones (P = 0.037, P = 0.023, Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Dysregulated estrogen signaling contributes to the initiation and progression of renal cell carcinomas,21,31 but the mechanism has not been well established.32,33 Our study here investigated the expression of ERα36 in renal tumors, which provide further insight in this field. ER expression is observed in both reproductive and nonreproductive tissues and cancer tissues.34 We provided evidences that ERα36 expression was correlated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma, which indicated ERα36 may be involved in tissue responsiveness to estrogens for carcinogenesis and progression.

High expression of ERα36 was an independent predictor for poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Different from the 66KDa ERα (ERα66), high ERα36 expression was observed on the plasma membrane and cytoplasm of renal cancer specimens.24,35 As a truncated isoform of ERα66, ERα36 gene completely matches with exon2 to exon6 of ERα66 gene.19,36 Some epitopes are shared by ERα36 and ERα66 proteins, which explain the cytoplasm pattern of ERα66 expression that was observed in renal carcinoma tissues.15 Here, the specific antibody for ERα36 was generated from the unique peptide in ERα36-C terminal. Molecular tests further guaranteed the specificity in IHC study in the tumor tissues. High levels of ERα36 expression were significantly correlated with necrosis in renal cell carcinoma, which is one of the most important prognostic factors. Further analyses were also confirmed that high ERα36 expression was correlated with increased metastasis and poor prognosis. Therefore ERα36 expression can be used as an independent predictive marker for the progression of renal cell carcinoma.

More importantly, membrane ERα36 expression is correlated worse prognosis relative to cytoplasm positive, which indicated that non-genomic estrogen signaling mediated by ERα36 may be involved in renal cell carcinoma progression. Different from those traditional nuclear receptor variants, ERα36 is located on membrane and cytoplasm as reported in previous studies.37,38 The plasma membrane-localized ERα36 was proposed to transduce membrane-initiated estrogen signaling.39 When estradiol binds to the cell surface receptor, a rapid generation of cAMP is stimulated. The non-genomic estrogen signaling is transduced to activate RNA and protein synthesis,34 which regulates various physiopathological processes for carcinogenesis and progression,31,40 such as promoting cell proliferation and invasion.41 Thus, membrane located ERα36 and related signaling maybe responsible for tumor progression of renal cell carcinoma. However, further studies for the mechanism are required in the future.

Accurate classification is crucial for both diagnosis and therapeutic intervention in renal tumors. However, majority of renal tumors have unusual morphology that renders classification challenging,42 such as the differential diagnosis of renal tumors with tubulopapillary features includes metanephric adenoma and papillary renal cell carcinoma.1,2 Accurate classification relies on careful examination of clinical and pathological features and immunohistochemical characteristics. Here, we evaluated ERα36 subcellular location for renal tumor classification and found that ERα36 membrane location was rarely observed in benign tumors, which provide useful criteria for accurate diagnosis differentiation in renal tumors.

Different ERα variants play important roles for estrogen signaling dysregulation. No significant correlation was observed between ERα36 and ERα66 in our study. However, other ERα variants (such as ERα46) were not included in our IHC study because of the limitation of specific antibody for them. Further study is still needed for the interaction between different variants. Taken together, membrane located ERα36 may act a critical role for renal cell carcinoma initiation and progression. IHC staining for ERα36 can provide valuable information for diagnosis, prognostication, and personalized treatment of renal tumors.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DFS = disease-free survival, ERα = estrogen receptor alpha, HE = hematoxylin and eosin, IHC = immunohistochemistry, OS = overall survival, PBS = phosphate buffer solution, RCC = Renal cell carcinoma, ROC = receiver-operating characteristic, TMA = tissue microarray.

This study was supported in part by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, No. 2010CB529400), National Science and Technology Major Program (Grant No. 2011ZX09102-010-02), Shandong province science and technology development plan item (2013GSF11866).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (www.md-journal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Williamson SR, Eble JN, Cheng L, et al. Clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: differential diagnosis and extended immunohistochemical profile. Mod Pathol 2013; 26:697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson SR, Halat S, Eble JN, et al. Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma: similarities and differences in immunoprofile compared with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36:1425–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol 2015; 67:913–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 2009; 373:1119–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volpe A, Patard JJ. Prognostic factors in renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol 2010; 28:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiklund F, Tretli S, Choueiri TK, et al. Risk of bilateral renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:3737–3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabat GC, Silvera SA, Miller AB, et al. A cohort study of reproductive and hormonal factors and renal cell cancer risk in women. Br J Cancer 2007; 96:845–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkman H. Estrogen-induced tumors of the kidney. III. Growth characteristics in the Syrian hamster. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1959; 1:1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberley TD, Gonzalez A, Lauchner LJ, et al. Characterization of early kidney lesions in estrogen-induced tumors in the Syrian hamster. Cancer Res 1991; 51:1922–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hontz AE, Li SA, Salisbury JL, et al. Expression of selected Aurora A kinase substrates in solely estrogen-induced ectopic uterine stem cell tumors in the Syrian hamster kidney. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008; 617:411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas C, Gustafsson J-Å. The different roles of ER subtypes in cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu CP, Ho JY, Huang YT, et al. Estrogen inhibits renal cell carcinoma cell progression through estrogen receptor-beta activation. PLoS One 2013; 8:e56667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung YS, Lee SJ, Yoon MH, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha is a novel target of the Von Hippel-Lindau protein and is responsible for the proliferation of VHL-deficient cells under hypoxic conditions. Cell Cycle 2012; 11:4462–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron RI, Ashe P, O’Rourke DM, et al. A panel of immunohistochemical stains assists in the distinction between ovarian and renal clear cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003; 22:272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langner C, Ratschek M, Rehak P, et al. Steroid hormone receptor expression in renal cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 182 tumors. J Urol 2004; 171 (2 pt 1):611–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivantsov AO, Imianitov EN, Moiseenko VM, et al. Expression of Ki-67, p53, bcl-2, estrogen receptors alpha in patients with clear cell renal carcinoma and epidermal growth factor receptor mutation. Arkh Patol 2011; 73:6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Lu Y, He Z, et al. Expression analysis of the estrogen receptor target genes in renal cell carcinoma. Mol Med Rep 2015; 11:75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogushi T, Takahashi S, Takeuchi T, et al. Estrogen receptor-binding fragment-associated antigen 9 is a tumor-promoting and prognostic factor for renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 2005; 65:3700–3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZY, Zhang XT, Shen P, et al. A variant of estrogen receptor-α, hER-α36: transduction of estrogen-and antiestrogen-dependent membrane-initiated mitogenic signaling. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:9063–9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin SL, Yan LY, Liang XW, et al. A novel variant of ER-alpha, ER-alpha36 mediates testosterone-stimulated ERK and Akt activation in endometrial cancer Hec1A cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2009; 7:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang XT, Kang L, Ding L, et al. A positive feedback loop of ER-α36/EGFR promotes malignant growth of ER-negative breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2010; 30:770–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang L, Wang L, Wang ZY. Opposite regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha and its variant ER-alpha36 by the Wilms’ tumor suppressor WT1. Oncol Lett 2011; 2:337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Li J, Fang R, et al. Expression of ERα36 in gastric cancer samples and their matched normal tissues. Onco Lett 2012; 3:172–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, Dong B, Li ZW, et al. Expression of ER-alpha 36, a novel variant of estrogen receptor alpha, and resistance to tamoxifen treatment in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:3423–3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan X, Zhou T, Tai Y-H, et al. Elevated expression of CUEDC2 protein confers endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat Med 2011; 17:708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Søreide K. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic, prognostic and predictive biomarker research. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y-C, Wu L, Yan L-F, et al. Predicting subtypes of thymic epithelial tumors using CT: new perspective based on a comprehensive analysis of 216 patients. Sci Rep-UK 2014; 4:6984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vavallo A, Simone S, Lucarelli G, et al. Pre-existing type 2 diabetes mellitus is an independent risk factor for mortality and progression in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Medicine 2014; 93:e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jing W, Chen Y, Lu L, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells producing IL15 eradicate established pancreatic tumor in syngeneic mice. Mole Cancer Ther 2014; 13:2127–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu YL, Lu Q, Liang JW, et al. High plasma fibrinogen is correlated with poor response to trastuzumab treatment in HER2 positive breast cancer. Medicine 2015; 94:e481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yue W, Yager JD, Wang JP, et al. Estrogen receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms of breast cancer carcinogenesis. Steroids 2013; 78:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka Y, Sasaki M, Kaneuchi M, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha polymorphisms and renal cell carcinoma: a possible risk. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003; 202:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mai KT, Teo I, Belanger EC, et al. Progesterone receptor reactivity in renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology 2008; 52:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou W, Slingerland JM. Links between oestrogen receptor activation and proteolysis: relevance to hormone-regulated cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14:26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng H, Huang X, Fan J, et al. A variant of estrogen receptor-alpha, ER-alpha36 is expressed in human gastric cancer and is highly correlated with lymph node metastasis. Oncol Rep 2010; 24:171–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Zhang X, Shen P, et al. Identification, cloning, and expression of human estrogen receptor-α36, a novel variant of human estrogen receptor-α66. Biochem Bioph Res Co 2005; 336:1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang XT, Ding L, Kang LG, et al. Involvement of ER-alpha36, Src, EGFR and STAT5 in the biphasic estrogen signaling of ER-negative breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2012; 27:2057–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang L, Zhang X, Xie Y, et al. Involvement of estrogen receptor variant ER-alpha36, not GPR30, in nongenomic estrogen signaling. Mol Endocrinol 2010; 24:709–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giuliano M, Schifp R, Osborne CK, et al. Biological mechanisms and clinical implications of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Breast 2011; 20 (suppl 3):S42–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Wang ZY. Estrogen receptor-alpha variant, ER-alpha36, is involved in tamoxifen resistance and estrogen hypersensitivity. Endocrinology 2013; 154:1990–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gu Y, Chen T, Lopez E, et al. The therapeutic target of estrogen receptor-alpha36 in estrogen-dependent tumors. J Transl Med 2014; 12:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasad SR, Humphrey PA, Catena JR, et al. Common and uncommon histologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma: imaging spectrum with pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2006; 26:1795–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]