Abstract

Death certificates serve the critical functions of providing documentation for legal/administrative purposes and vital statistics for epidemiologic/health policy purposes. In order to satisfy these functions, it is important that death certificates be filled out completely, accurately, and promptly. The high error rate in death certification has been documented in multiple prior studies, as has the effectiveness of educational training interventions at mitigating errors. The following guide to death certification is intended to illustrate some basic principles and common pitfalls in electronic death registration with the goal of improving death certification accuracy.

Keywords: Death certification, Electronic death registration, Death record, Cause of death, Manner of death

The death certificate is an important legal document. In addition to providing the decedent’s family with a cause of death, it has critical administrative and epidemiologic applications. Death certificates may be required to settle decedents’ estates and obtain insurance or other pensions/benefits. In many states, death certification is required prior to cremation or burial services. At both the state and national level, mortality data compiled from death certificates is used to track disease trends, set public health policies, and allocate health and research funding.1,2 For these reasons, it is important that death certificates be filled out completely, accurately, and promptly.

In most states, there is a specified time within which the death certificate must be filed. For instance, in the State of Wisconsin, physicians are required to complete and return the medical certification portion of the death certificate within a maximum of 6 days of the date of death pronouncement,3 and it is considered a Class I felony to “willfully and knowingly” supply false information on a death certificate.4 Despite the importance of accurate death certification, errors are common. Studies at various academic institutions have found errors in cause and/or manner of death certification to occur in approximately 33% to 41% of cases,5–7 with disproportionate overrepresentation of cardiovascular causes of death.8,9 Among the reasons most commonly cited for major errors in certification are physician inexperience (eg, resident physicians) and lack of appropriate death certification training. When brief educational interventions such as didactic seminars or distribution of printed guidelines are made, error rates have been shown to decrease markedly.7,9 For instance, in one study of 200 resident physicians asked to complete a cause-of-death statement from a sample hospital death case, only 15.5% correctly identified the cause of death. Following either a workshop or review of printed guidelines, 84.5% could correctly identify the cause of death.9 The following review is intended to educate medical certifiers about basic principles and common pitfalls of electronic death registry and certification in order to improve accuracy. While some of the principles discussed herein apply to perinatal deaths, the general topic of perinatal (ie, fetal and infant) death certification has very different practical considerations and challenges that are beyond the scope of the current review.

Pronouncement of Death

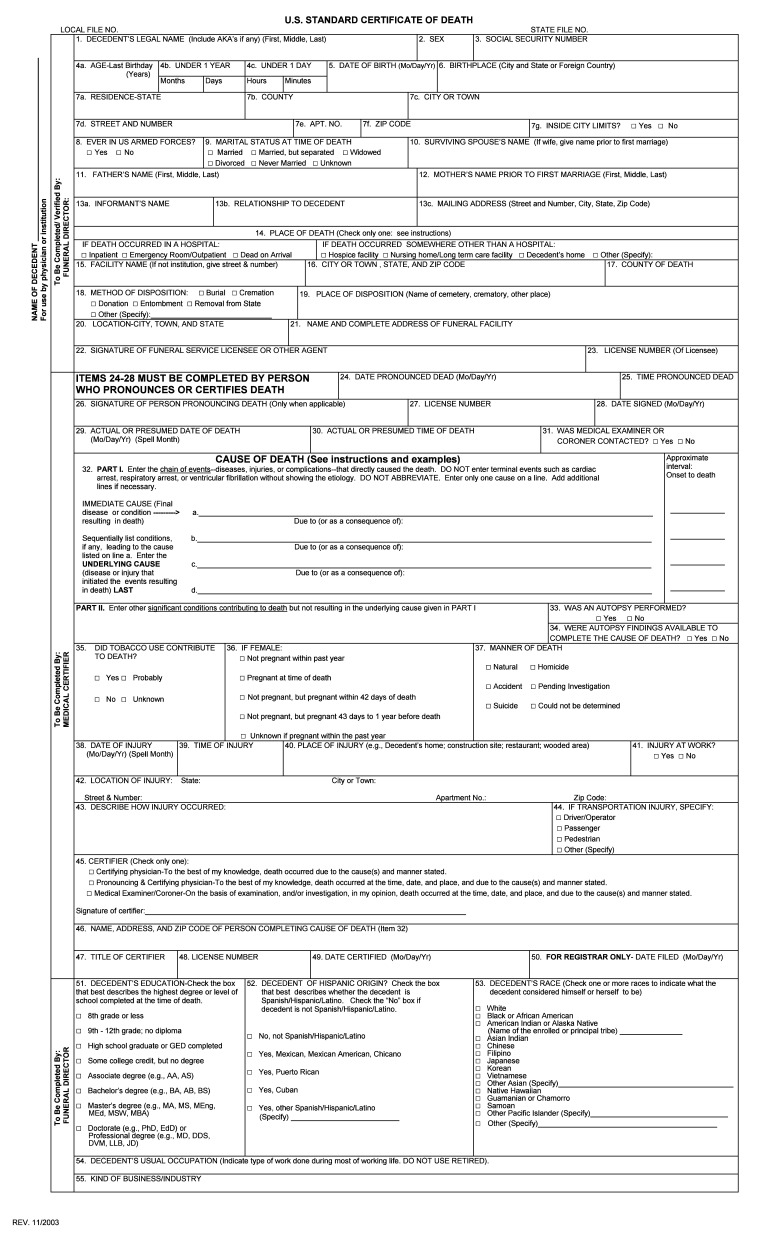

While there may be some minor variability between states, most death certificates conform in content and structure to the US Standard Certificate of Death (figure 1).1 There are three main categories of information contained on the standard death certificate: demographics/statistics (eg, name, social security number, race, occupation), method/place of bodily disposition (eg, funeral home, burial vs. cremation, cemetery site), and death information (eg, date and time, cause, manner).1,2 Only certain individuals are qualified to officially pronounce death. For instance, in the state of Wisconsin, death can be pronounced by a physician, hospice nurse, medical examiner/coroner (ME/C), or deputy ME/C.10 While in some states medical examiners are required to be medical doctors, in Wisconsin this is not necessarily so. The term ‘pronouncement’ refers to the date and time when the individual was found to be legally dead and, particularly in ME/C cases, may not always correspond to the time death is actually suspected to have occurred. For instance, an individual expiring alone in a secured residence may not actually be discovered and pronounced dead until days afterward (table 1).

Figure 1.

U.S. Standard Certificate of Death.

Table 1.

Definitions of terminology involved in certifying death.

| Pronouncement of Death | Date and time an individual was found to be legally dead. May be pronounced by a physician, medical examiner, or coroner. |

| Date and Time of Death | Date and time an individual is thought to have really died: may be actual or estimated by a physician, medical examiner, or coroner. |

| Cause of Death | Causal chain of events (disease or injury) that directly led to the death. |

| Immediate Cause of Death | Final event in the causal sequence that occurred closest to the time of death. Filled in as top line diagnosis on death certificate. |

| Underlying Cause of Death | Initiating event in the causal sequence that occurred most remote from the time of death. Filled in as bottom line diagnosis on death certificate. |

| Manner of Death | Classification of death based on circumstances surrounding it, i.e. suicide, homicide, accident, natural, or undetermined. |

| Medical Certifier of Death | Individual completing the medical portion of the death certificate including time, cause, and manner of death. |

Electronic Death Registry

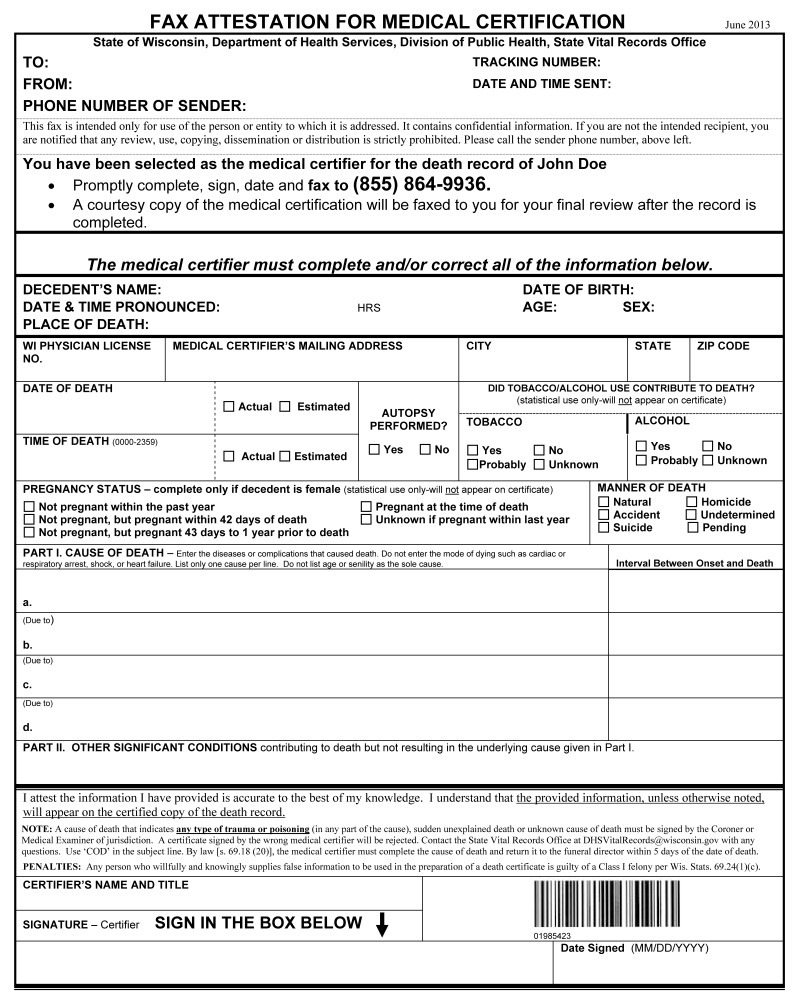

After pronouncement of death, the funeral director can initiate the death record and fill-in the non-medical portions of the death certificate. In most states, this process now occurs electronically. For instance, the state of Wisconsin began using an electronic death filing system (Statewide Vital Records Information System–SVRIS) on September 1, 2013. Advantages to an electronic death registry system include improved death certification timeliness and efficiency, better quality mortality data, and increased potential for real-time mortality surveillance.11 In SVRIS (or equivalent electronic death filing systems in other states), the funeral director can fill in the decedent’s demographic, statistical, and bodily disposition information, select the appropriate medical certifier, and then promptly fax a “Fax Attestation for Medical Certification” form to the physician’s office (figure 2).12,13 The faxed attestation form consists of the portion of the death certificate that can only be completed by a medical certifier of death. Most states have statutes detailing which individuals are qualified as medical certifiers; for instance, in Wisconsin, physicians, chief medical officers of the hospital or nursing home where death occurred, coroners, and medical examiners are all potential medical certifiers. Generally, the decedent’s attending or personal physician is considered best qualified to be the certifying physician. While convenient to have the same physician both pronounce and certify a death, it is not required. Following completion and signature of the attestation form, the certifying physician can fax it to SVRIS (1-855-864-9936). A fax image is then associated with the death record: the funeral director can verify the information faxed by the medical certifier and complete the record.12 A courtesy copy of the medical certification is faxed to the physician certifier for final review; if any errors are noted by the certifier, changes can be made to a paper copy, signed, dated, and faxed back to SVRIS.

Figure 2.

Fax attestation for medical certification.

Medical Certification of Death

Items collected on this portion of the death certificate (figure 2) should be completed by the medical certifier of death, starting where the faxed attestation form states “The medical certifier must complete and/or correct all of the information below.” The information includes the actual or presumed date and time of death (table 1). In hospitalized patients, this will often be the same as the date and time of pronouncement. All dates should be indicated in terms of month, day, and year, and all times should be indicated in terms of a 24-hour clock (ie, military time). Other items that must be checked off include specifying the decedent’s pregnancy status at the time of death, clarifying whether alcohol or tobacco usage contributed to death, indicating manner of death, and indicating whether an autopsy was performed.1,13 In Wisconsin, either a partial or full autopsy would be checked “yes,” while an external examination would be checked “no.” Arguably, the most statistically useful information contained on this portion of the death certificate, though, is the cause-of-death section.1

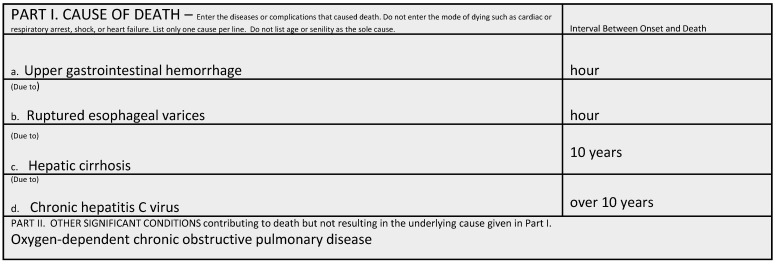

For mortality research purposes, it is important that the cause-of-death section be reported as specifically as possible. The cause-of-death section is divided into two parts. Part I is used to report the causal chain of events leading to death. The most recent or “immediate” condition that led to death is placed on Line a; other conditions (if any) that gave rise to the immediate cause of death are listed sequentially on Lines b–d.1,2 The last and most remote condition in the chain of events leading to death is known as the “underlying” cause of death, and should be etiologically specific. Conditions falling between the first and last are considered “intermediate” or “intermediary” causes of death (table 1). Only one cause should be listed per line. The approximate interval between presumed onset and date of death should be given for each condition listed in Part I.1,2 Generic intervals such as “minutes” “hours” “weeks” “months” “years” “are acceptable if more precise intervals are unknown. Part II is used to report all other significant conditions (such as diseases or injuries) that contributed to death, but did not necessarily result in the chain of events documented in Part I. Multiple conditions can be listed together in Part II. The following examples are intended to illustrate general cause-of-death certification principles (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Example illustrating the importance of specificity in death certification.

Specificity is key

In this example, upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage would represent the immediate cause of death, while chronic hepatitis C virus infection would represent the underlying etiologically specific cause of death. The sequence provides an accurate and chronologic explanation of the events leading to death. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is specified in Part II because, although not directly related to the conditions listed in Part I, baseline significant compromise of respiratory function would have made the decedent less able to tolerate the stress of sudden blood loss and, thus, contributed to death. It is recommended to be as specific as possible when listing conditions causing death: specific infectious etiologic agents or specific anatomic locations of lesions should be indicated if known (eg, ‘hepatitis C virus’ rather than ‘chronic hepatitis’ and ‘upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage’ rather than ‘gastrointestinal hemorrhage’).14 Also, note that abbreviations (eg, HCV, COPD, UGI) should be avoided when formulating cause-of-death statements.

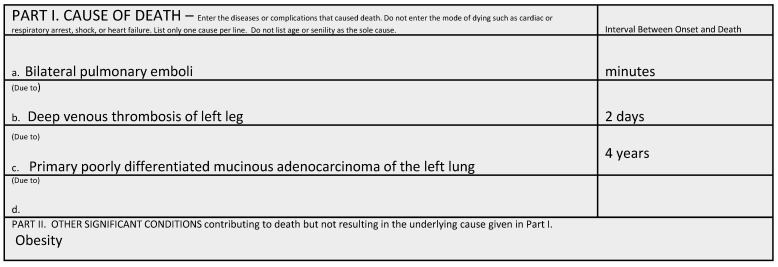

Cause not mechanism

In this example (figure 4), the patient died in cardiorespiratory arrest. Cardiorespiratory arrest is not listed as line diagnosis, however, because it is a non-specific terminal mechanism rather than a cause of death. Other terminal mechanistic descriptions to be avoided on death certificates include ‘asystole’ or ‘electromechanical dissociation.’2,14 By avoiding such terms, lines can be preserved for diagnoses that convey useful mortality information, such as bilateral pulmonary emboli. The emboli in this case arose from previously detected deep venous thrombi. The patient was predisposed to venous thrombosis due to malignancy-related hypercoagulability. Note that when indicating malignancy as a cause of death, it is recommended to specifically include the primary site, cell type, tumor grade, stage/metastases (eg, primary poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma of the left lung), or otherwise to indicate that this information is unknown.1 Obesity is specified in Part II because it is a known risk factor for venous thromboembolism and also could have compromised respiratory function.

Figure 4.

Example illustrating the importance of identifying cause not mechanism in death certification.

Best medical opinion

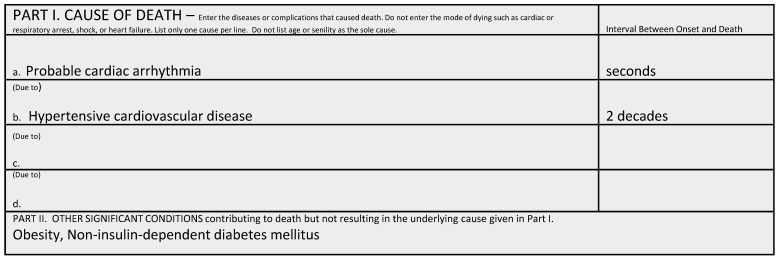

In some cases (figure 5), the causal chain of events leading to death is not clear. If there is an element of uncertainty, using qualifiers such as ‘probable’ and ‘presumed’ is acceptable. In general, the degree of certainty required of a natural death certifier is ‘more likely than not’ (ie, with a reasonable degree of medical probability the decedent expired of the causes listed on the death certificate).2,14 Particularly with elderly decedents, it can be challenging to prioritize the conditions leading to death, as there are often multiple medical comorbidities, and they can appear to die with (rather than of) their disease.14 Terms such as ‘senescence,’ ‘infirmity,’ and ‘advanced age’ should be avoided, as the age is already documented elsewhere on the death certificate.1 If there is no medically probable cause of death, then requesting an autopsy or notifying the ME/C may be necessary. A ‘pending’ death certificate can be issued while awaiting autopsy or other critical testing results; in Wisconsin, a supplemental certificate must then be issued to the state registrar within 30 days of pronouncement of death.15 Note that it is not necessary to use all lines in Part I, as seen above. Conversely, extra lines may be added if needed.

Figure 5.

Example showing detail for a best medical opinion of cause of death when the chain of events leading to death are not clear.

The bottom line

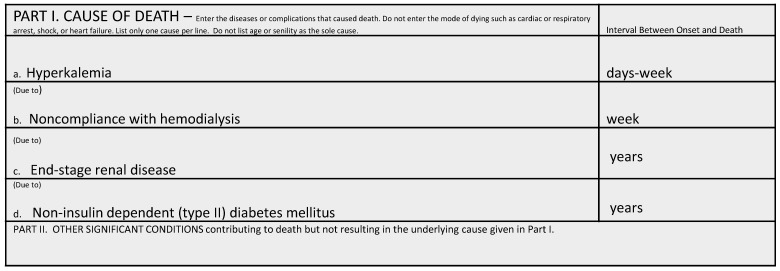

The condition listed on the bottom line of Part I (ie, the underlying cause of death) is arguably the most important in that this is generally what will be coded as the cause of death. Mortality data worldwide are coded according to the current International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) system that is published by the World Health Organization (WHO).16 The system facilitates interpretation and comparison of mortality data by translating the cause of death into an alphanumeric code that corresponds to a particular disease or injury. From a public health perspective, the most effective strategy is to prevent the initiating disease or injury that precipitated the chain of events leading to death.16 For this reason, it is important to carefully consider underlying causes. In the current example (figure 6), end-stage renal disease has many possible etiologies. It is important that type II diabetes mellitus be specified as the underlying cause of death in order to ensure accurate tracking of disease mortality. The need for better-standardized death certification and coding practices in diabetes-related deaths has been alluded to previously.17

Figure 6.

Example showing the underlying cause of death listed on the last line of Part I.

Mind Your Manners

Manner of death refers to how the death came about. It classifies deaths based on the circumstances surrounding the probable cause. In Wisconsin (as in most states), there are five possible manners of death: natural, accident, suicide, homicide, and undetermined.2,16 In select jurisdictions in some states, therapeutic complication is an additional option.17 A natural death is defined as one resulting solely from disease and/or age. In Wisconsin, as in most states, these are the only deaths non-medical examiner physicians should certify. If the manner appears to be accidental, suicidal, homicidal, undetermined (or occurs in circumstances that are unexplained, unusual, or otherwise suspicious) then the case should be reported to the county ME/C.13,18 By definition, all sudden infant deaths, in-custody deaths, and deaths following abortion should be reported to the ME/C. Accidental deaths are defined as those in which unintentional injury or poisoning contributed to or caused the death. Suicides are defined as deaths resulting from injury or poisoning, self-inflicted with the intent to do self-harm or cause death. Homicidal deaths are those in which death occurs due to injury or poisoning resulting from the volitional act of another. When there is insufficient information to classify the death, it is classified as undetermined. The following examples are intended to illustrate manner of death classification principles and pitfalls:

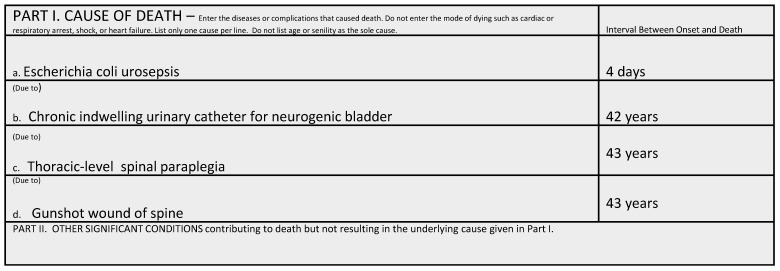

Injuries have no statute of limitations

In this example (figure 7), the patient expired of urosepsis arising as a direct complication of neurogenic bladder due to a paralyzing gunshot wound of the spine. The manner of death in this case would be considered a homicide, despite the many intervening years since the injury.2,14,16 In general, if the cause of death can clearly be traced to the effects/complications of an injury, the case should be reported to a ME/C office regardless of the interval length between injury and death. In the elderly, a common example of this principle would be hip fractures. Hip fractures place patients at high risk of sequelae such as infection and thromboembolic events; it has been reported that one in five elderly hip fracture patients die within a year of injury.19 If a hip fracture was sustained in a fall after which the patient never returned to baseline functional status, and death appears due to sequelae of the fracture, then the manner of death would be accident.14,20 In general, if the death would not have occurred had the patient not sustained a preceding traumatic injury (or acute drug toxicity), the manner is considered non-natural. Note that by convention, even if an injury or drug toxicity is only listed in Part II as a contributory condition, the non-natural condition prevails and determines the manner of death in the case.20

Figure 7.

Example to illustrate injuries, as underlying cause of death, have no statute of limitations.

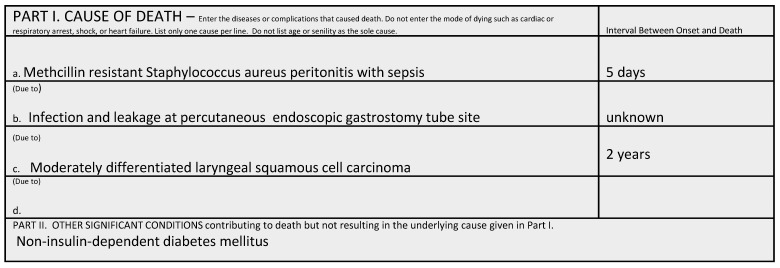

Therapeutic complications

In this example (figure 8), the patient developed peritonitis and sepsis as a result of infection and leakage at the gastrostomy tube site that had been inserted due to laryngeal carcinoma-related dysphagia. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes are reported to have a significant rate of complications and early mortality; in one large series, 10% and 11% of patients developed leakage and peristomal infection, respectively, within 2 weeks of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion.21 In this case, because the death occurred due to reasonable and predictable complications of an accepted therapy for underlying natural disease, the manner of death would be classified as natural. In cases in which death occurs due to defective or unintentionally misused medical equipment, or complications seem excessive given the therapeutic procedure, the manner of death would be designated accident.2,14,15 Note that if therapeutic complications arise during treatment of a potentially life-threatening injury (eg, emergent surgery for multiple stab wounds of the chest), the circumstances surrounding the injury dictate the manner of death (eg, homicide).17 In challenging cases, it may be helpful to consult with the ME/C office, as well as a specialist in the particular therapeutic/surgical procedure.

Figure 8.

Example illustrates cause of death due to therapeutic complications.

Acute versus chronic substance abuse

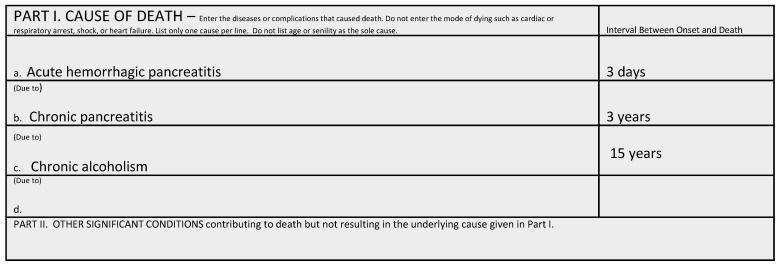

In this example (figure 9), the patient developed acute pancreatitis superimposed on chronic pancreatitis due to chronic alcohol abuse. Consequences of chronic alcohol abuse such as pancreatitis, alcohol withdrawal seizures or alcoholic cirrhosis are conventionally designated as natural deaths.2,15 Other common examples of chronic substance abuse resulting in natural deaths would include endocarditis due to chronic intravenous drug use, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to tobacco smoking or oral carcinoma due to tobacco chewing. Conversely, deaths due to acute substance toxicity such as acute alcohol poisoning, cocaine-induced excited delirium, or acute multidrug toxicity are conventionally designated as accidents or suicides (depending on whether there was evidence of intent to do self-harm or cause death).2,15 Note that when death occurs due predictable toxicity of a substance medically prescribed for the treatment of underlying natural disease (eg, sepsis arising in the setting of chemotherapeutic marrow immunosuppression for malignancy), the death would generally be classified as natural.2,15

Figure 9.

Example illustrates cause of death from a chronic disease underlying acute presentation of illness.

Making Amends

The reported cause of death is the best medical opinion of the certifier, and it is understood that this opinion may change if additional information later becomes available. Most states have provisions to amend death certificates. For instance, in Wisconsin, the certifying physician may amend a cause of death for up to one year following death pronouncement without requiring a court order. The certifier should submit a signed and dated letter indicating the item requiring amendment to the state registrar. After a year has passed, or if an item has already been amended once before, a court order is required.15 In cases in which an autopsy has been requested, it may be simplest to wait to certify the death until the preliminary autopsy findings are available.22 Usually the preliminary report is issued within 1 to 2 days of autopsy; clinicians can also directly contact the autopsy pathologist if more immediate information is desired. In some cases, final autopsy results are required before cause of death can be accurately determined; in such cases, a ‘pending’ death certificate can be issued, as previously discussed. At some institutions, it is the policy that the autopsy pathologist (in consultation with the attending physician) assumes responsibility for certifying the death in cases in which autopsy is performed.14 Advantages to this approach include extremely good concordance between autopsy findings and cause-of-death certification. Should additional information become available indicating the manner of death may no longer be natural, the county ME/C should be consulted to make necessary death certificate changes.

Summary

Death certificates serve two critical functions: providing documentation for legal/administrative purposes and vital statistics for epidemiologic/health policy purposes. To satisfy both of these functions, it is important that death certificates be filled out completely, accurately, and promptly. The high error rate in death certification has been documented in multiple prior studies, as has the effectiveness of educational training interventions at mitigating errors. This guide to death certification is offered with the intent of illustrating some basic principles and common pitfalls in electronic death registration. It is hoped that such education will serve as a means to help achieve greater accuracy and standardization among physician certifiers in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclosure and received no sources of financial support in writing this review.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Physicians’ handbook on medical certification of death, Hyattsville, Md.: Government Printing Office, 2003. DHHS publication no. (PHS)2003–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanzlick RL. Medical certification of death and cause-of-death statements. In: Collins KA, Hutchins GM, eds. Autopsy Performance and Reporting. 2nd ed Northfield, IL: College of American Pathologists; 2003. 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wisconsin State Legislature. Wisconsin Statute. Medical Certification § 69.18(2)(b) (2013–2014).

- 4.Wisconsin State Legislature. Wisconsin Statute. Penalites § 69.24(1)(c) (2013–2014).

- 5.Pritt BS, Hardin NJ, Richmond JA, Shapiro SL. Death certification errors at an academic institution. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:1476–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sehdev AE, Hutchins GM. Problems with proper completion and accuracy of the cause-of-death statement. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers KA, Farquhar DR. Improving the accuracy of death certification. CMAJ. 1998;158:1317–1323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakkireddy DR, Gowda MS, Murray CW, Basarakodu KR, Vacek JL. Death certificate completion: how well are physicians trained and are cardiovascular causes overstated? Am J Med 2004;117:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakkireddy DR, Basarakodu K, Vacek J, Kondur AK, Ramachandruni SK, Esterbrooks DJ, Markert RJ, Gowda MS. Improving death certificate completion: a trial of two training interventions. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:544–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wisconsin State Legislature. Wisconsin Statute. Definitions § 69.01(6g) (2013–2014).

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Improvements to the National Vital Statistics System. April 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/ImproveNVSS_2014.pdf Accessed January 10, 2015. [PubMed]

- 12.Department of Health Services State of Wisconsin. Wisconsin’s statewide vital records information system (SVRIS): funeral home user manual. June 2013. Department of Health Services Division of Public Health publication no. P-00550; Available at: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p0/p00550a.pdf Accessed January 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health Services State of Wisconsin. Statewide vital records information system handout-Fax Attestation (VR-4). June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanzlick R. (ed) and the Autopsy Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Cause of death statements and certification of natural and unnatural deaths (Manual). College of American Pathologists; Northfield, Ill: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisconsin State Legislature. Wisconsin Statute. Death Records § 69.18(2)(f). (2013–2014).

- 16.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. Volume 2 Available at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ Accessed April 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao C, Doi SA. Measuring population-based diabetes-related mortality: a summary of requirements. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:237–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanzlick R, Hunsaker JC, Davis GJ. A guide for manner of death classification. 1st ed Atlanta, GA: National Association of Medical Examiners, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill JR, Maloney KF, Hirsch CS. The consistency and advantage of therapeutic complication as a manner of death. Acad Forensic Pathol 2012;2:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisconsin State Legislature. Wisconsin Statute. Reporting deaths required; penalty; taking specimens by coroner or medical examiner § 979.01 (2013–2014).

- 21.Farahmand BY, Michaelsson K, Ahlbom A, Ljunghall S, Baron JASwedish Hip Fracture Study Group. Survival after Hip Fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2005;16:1583–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolinak D, Matshes E. Death certification. In: Dolinak D, Matshes E, Lew E, eds. Forensic pathology: principles and practice. Burtlington, MA: Elsevier; 2005. 663–668. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blomberg J, Lagergren J, Martin L, Mattsson F, Lagergren P. Complications after percutaneous endoscopic gastroscopy in a prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2012;47:737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AE, Hutchins GM, Hanzlick R. Case of the month: making amends. Autopsy Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1739–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]