Abstract

Most existing research theorizes individual factors as predictors of perceived job insecurity. Incorporating contextual and organizational factors at an information technology organization where a merger was announced during data collection, we draw on status expectations and crossover theories to investigate whether managers’ characteristics and insecurity shape their employees’ job insecurity. We find having an Asian as opposed to a White manager is associated with lower job insecurity, while managers’ own insecurity positively predicts employees’ insecurity. Also contingent on the organizational climate, managers’ own tenure buffers, and managers’ perceived job insecurity magnifies insecurity of employees interviewed after a merger announcement, further specifying status expectations theory by considering context.

Keywords: Perceived job insecurity, managers, merger announcement, status expectations, crossover

The employment relationship has undergone many changes, given the globalization and turbulence of the economy, the rise in employment instability, and corollary increases in perceived job insecurity for both men and women (Fullerton and Wallace 2007; Green, Felstead and Burchell 2000; Hollister 2012; Kalleberg 2009). Moreover, scholars find evidence of an adverse relationship between perceived job insecurity and employees’ health, well-being, and job attitudes (De Cuyper et al. 2010; Glavin 2013; Hellgren and Sverke 2003; Lam, Fan, and Moen 2014; Probst 2011; Probst and Brubaker 2001; Selenko et al. 2013). Most studies use individual-level data to investigate antecedents of perceived job insecurity (Farber 2008; Fullerton and Wallace 2007; Fullerton and Anderson 2013; Wilson, Eitle, and Bishin 2006). Extant studies typically link employees’ race, age, or education to their perceived insecurity, but have generally neglected the fact that employees are always located in particular organizational contexts.

This paper contributes to and extends existing understanding of job insecurity by bringing “the firms back in” (Baron and Bielby 1980) in considering differences in employees’ perceived job insecurity, contextualizing their experiences within a Fortune-500 company, with managers a key component of that context (c.f. Klandermans and van Vuuren 1999). Given the focus of the literature is on the perception of insecurity, we draw on status expectations theory (Ridgeway 2014) to theorize that employees make inferences based on the status characteristics of their managers. We propose that their managers’ characteristics and insecurity are an important factor shaping employees’ own assessments of job insecurity. Further, we utilize a unique dataset, where some employees were interviewed before and some interviewed after the announcement of a merger. The serendipitous occurrence permits a test of whether managers’ characteristics magnify or ameliorate employees’ perceived job insecurity given knowledge of the organizational uncertainty of an impending merger.

Using cross-sectional data from 666 employees together with linked information on their front-line managers (N=176) in the information technology (IT) division of a Fortune 500 firm, we address three research questions: 1) Do the status characteristics of employees’ managers predict employees’ own perceived job insecurity? 2) Does being surveyed after a merger announcement relate to greater perceived job insecurity? 3) If employees surveyed after a merger announcement do report higher perceived job insecurity on average, do their managers’ status characteristics magnify or ameliorate employees’ perceived insecurity in this uncertain climate?

The Role of Managers

We draw on expectations states theory (Berger et al. 1977; Ridgeway 2001) as related to employees’ status beliefs about their managers. Specifically, we propose that managers’ characteristics – such as their gender, race, and tenure with the firm – lead the employees reporting to them to feel more (or less) protected at work. According to Ridgeway (2001, p. 638): “expectation states theory defines status beliefs as widely held cultural beliefs that link greater social significance and general competence, as well as specific positive and negative skills, with one category of social distinction (e.g., men) compared to another (e.g. women; Berger et al. 1977).” Status expectations can be contingent on processes operating within specific workplaces, as related to the goods or services provided by the organization, as well as associated with the traits emphasized in different social roles. For instance, Ridgeway (2001:638) points out that “evidence indicates that gender stereotypes do contain beliefs associating greater overall competence with men than women, particularly in more valued social arenas, while also granting each sex particular skills, such as mechanical ability for men and domestic skills for women.” In the evaluation of managers within the information technology workforce investigated in this study, we test whether employees might make the assessment that White and male managers with the longest tenure would have more clout and power to protect their direct reports from layoffs, given status expectations of managers with these characteristics. We choose a status expectation framework because we believe the main variable of interest—perceived job insecurity—represents employees’ cognitive assessments of their managers’ ability to stave off layoffs within their team. Such status beliefs tap into status perceptions by employees about the degree to which managers actually possess power or resources that will affect their own ability to remain employed in the organization (Ridgeway 2014). While our employee respondents may or may not have access to direct knowledge of their managers’ power or resources, we theorize that they nevertheless make inferences based on their managers’ status characteristics. Such status beliefs about their managers’ competence, resources, and power may be especially salient to employees’ assessment of their own job security (Ridgeway 2014).

This research builds on previous “micro” studies of individual job insecurity (Elman and O’Rand 2002; Fullerton and Wallace 2007) to investigate the “meso” context of work and analyzes managers’ influence on employees’ subjective experiences on the job (Briscoe and Kellogg 2011; Castilla 2011). Existing studies on job insecurity have already documented individual-level characteristics as predictors of perceived job insecurity (Fullerton and Wallace 2007). Employees’ own race, ethnicity, and age are associated with their perceived job insecurity (Fullerton and Wallace 2007; Fullerton and Anderson 2013; Wilson, Eitle, and Bishin 2006; Wilson and Mossakowski 2012). Specifically, Whites are less likely to feel insecure than non-Whites, and older/mid-career employees are more likely to feel vulnerable (Fullerton and Wallace 2007; Mendenhall et al. 2008; Newman 1999; Wilson and Mossakowski 2012). For example, one study using the 2000–2010 waves of the General Social Survey finds that the odds of high perceived job insecurity are 53% greater for African Americans and 77% greater for Hispanics, as compared to Whites (Fullerton and Anderson 2013). Those with less education also report higher perceived job insecurity (Elman and O’Rand 2002). Building on this literature on employees’ status characteristics, we test whether employees reporting to managers with different status characteristics may also report different levels of perceived job insecurity.

Status characteristics affect how employees are evaluated with regard to competence (Bell and Nkomo 2001; Roth 2004) and how employees fare on promotions, and the risk of termination (Ortiz and Roscigno 2009). We contend that employees may be making similar evaluations about their managers’ likelihood of being terminated or forced out.

Employees may hold status expectations about their managers that extend beyond ascriptive characteristics such as race and gender. For instance, Blair-Loy and Wharton (2002) hypothesized that a manager with longer organizational tenure may have more relative status. They find that powerful managers facilitate employees’ use of work-family policies. Following this line of reasoning, we theorize employees may perceive managers with longer tenure as more established and thus better able to protect them from layoffs, thereby lowering employees’ perceived job insecurity.

We hypothesize that employees make status expectations of their managers, with perceptions of managers’ higher status positively related to employees’ lower perceived job insecurity. This meso theoretical framing brings managers into the picture, thereby contextualizing employees’ assessments of their degree of job insecurity at the micro level.

Hypothesis 1: Managers’ characteristics are associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity, such that employees whose managers are male, White or have longer tenure report lower perceived job insecurity.

We also draw upon crossover theory (Bakker, Westman, and van Emmerik 2009; Westman 2001) to propose that managers’ assessments of their personal job insecurity “crossover” to shape their employees’ assessments of their own insecurity (Carlson et al. 2011; Westman, Etzion and Danon 2001; Westman 2001). In other words, employees whose managers perceive their jobs to be insecure are more apt to feel the same way about their own jobs.

More generally, crossover theory suggests that the strain or stress one person experiences could affect those sharing a common social environment (Westman and Etzion 1995). Research on crossover has considered how employees’ job insecurity crosses over to affect their spouses (Westman et al. 2001; Wilson, Larson and Stone 1993) and children (Barling, Zacharatos and Hepburn 1999; Barling, Dupre and Hepburn 1998; Lim and Sng 2006; Zhao, Lim and Teo 2012). For instance, previous studies have investigated parents’ job insecurity, finding an association with their young adult children’s work attitudes and beliefs (Barling et al. 1998), cognitive ability and academic performance (Barling et al. 1999), extrinsic and intrinsic motivation towards work (Lim and Sng 2006), and career self-efficacy (Zhao et al. 2012). In one study of 98 couples working for the same firm, Westman and colleagues (2001) find that the job insecurity of husbands and wives are positively correlated, suggesting that job insecurity might cross over from one to the other.

Given power differences and dynamics at the workplace, we might expect an even greater crossover effect of insecurity from managers to their direct reports. We theorize when managers are themselves insecure and at risk of losing their own jobs, employees may perceive managers as no longer able to protect them from the risk of layoff, in turn reporting higher job insecurity. We draw on data with individual IT employees and managers nested in teams, to test whether having a manager with high job insecurity in fact translates into employees’ own higher perceived insecurity.

Hypothesis 2: Managers’ perceived job insecurity is positively associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity, such that employees reporting to a manager with higher job insecurity are also more likely to report higher job insecurity.

The Uncertainty of an Unexpected Merger Announcement

Our second set of research questions examines whether employees surveyed right after a merger announcement report higher perceived job insecurity, as well as whether specific characteristics of managers buffer (or conversely magnify) knowledge of an impending merger. Seldom are scholars able to be “on the ground” when major organizational restructuring occurs. A few longitudinal studies have followed employees in specific workplaces as they restructured over time, but these have primarily been studies of public employees in Europe, such as in the UK, Finland and the Netherlands (Ferrie et al. 1998; Kivimaki et al. 2000, 2001; Swaen et al. 2004).

Existing studies have largely focused on actual downsizing and characteristics of those who are laid off (Dencker 2008; Elvira and Zatzick 2002; Fernandez 2001; Kalev 2014), while less is known about perceived job insecurity once an unexpected restructuring is announced. We use the announcement of an impending organizational change occurring in the middle of data collection as a defining break in the organizational climate to investigate the possibility of a different relationship between manager status characteristics and employees’ perceived job insecurity for those who knew about an upcoming merger when they were interviewed, compared to those who were interviewed before the merger announcement was made. We assess whether managers’ characteristics might be even more strongly associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity for those interviewed after the merger was announced, as employees might look to their managers to a greater extent for a sense of security and direction during this period of uncertainty.

Hypothesis 3: Employees surveyed after the announcement of a merger will report higher perceived job insecurity.

Hypothesis 4: Manager characteristics (gender, race, tenure, manager’s perceived insecurity) may be more predictive of employees’ job insecurity in a precarious organizational climate (in this case, for those surveyed after the announcement of a merger).

In sum, this study builds on and extends a larger recent literature underscoring manager effects on employees, such as consequences for utilizing flexible work policies, access to reputation-building projects and career outcomes, and influencing other managers’ evaluation of employees’ performance (Blair-Loy and Wharton 2002; Briscoe and Kellogg 2011; Castilla 2011). To do so, we draw on both status expectations theory and crossover theory to assess whether managers’ characteristics, including their own assessment of their personal job insecurity, are associated with employees’ perceptions of job insecurity. We also consider the organizational climate, testing whether managers play an even greater role in shaping employees’ perceived security or insecurity when employees have just learned that their firm will be undergoing significant restructuring.

Study Site and Method

We draw on data from the Work, Family & Health Network Study (WFHN), a group randomized experiment carried out in the IT division of a Fortune-500 company, given the pseudonym TOMO (see Bray et al. 2013, King et al. 2012). The IT division of this company develops new software for the company’s external business as well as internal needs and maintains the software systems that are an essential part of this organization’s business. Some employees in the study focus primarily on the core business of the division (i.e., software development) while others support the development teams through operational, quality assurance, and programmatic support.

In the IT division, employees are organized into work teams, with each having a primary manager guiding their overall work. These work teams are organized under Directors who report to Vice Presidents who focus on either development tasks and quality assurance or the support and programmatic part of the business. Vice Presidents and Directors were not surveyed in the study, but front-line managers supervising employees were.

The study draws on computer-assisted personal interviews lasting about 60 minutes conducted by trained field interviewers at the workplace on company time. The surveys were connected through team identifiers permitting us to link responses from employees and their supervising managers.

Overall, 1,182 employees in the IT division were eligible to complete the survey and 823 did so, for a 69.6% response rate. Employees’ managers were surveyed as well, with 256 managers eligible and 221 managers responding, for an 86.3% response rate. We employed listwise deletion based on item non-response, resulting in an analytic sample of 666 employees.i Tests of differences between individuals in our analytic sample and those excluded due to missing variables show that respondents in our analytic sample are more likely to have heard about the merger (57% vs. 35%, p<0.001). Respondents are also more likely to have a college degree (80% vs. 67%, p<0.001), and to report to a manager with longer tenure (16.75 years vs. 12.73 years; p<0.05).

During the course of data collection, a merger was announced by top executives, and received immediate attention by the media and the employees at the company. Given that the merger was announced at one point in time even as employees, managers, and their work teams were staggered in their completion of the surveys (depending on when they were randomly assigned to do so over a period of a year), comparison groups emerged based on the timing of when respondents were surveyed in relation to learning about the merger. More than half (57%) of the employee respondents in our analytic sample completed the survey prior to the merger announcement, while the remainder of the sample (43%) took the survey after this upcoming change was announced.

Measures

Dependent Variable

Perceived Job Insecurity is based on one item that asks, “In the next twelve months, how likely are you to lose your job or be laid off?” with four responses from 1 “not at all likely” to 4 “very likely.” This single-item measure is a commonly used indicator of job insecurity (Burgard, Kalousova and Seefeldt 2012; Fullerton and Wallace 2007).

Employee Variables

Our focal merger knowledge variable has to do with whether individuals knew about the merger at the time they were surveyed, with 1 indicating that the individual’s interview was completed after the merger announcement. Demographic characteristics include: Female, Age, and Age-Squared. We include Age-Squared to determine if the effect of age may be non-linear. We test this given a prior study by Fullerton and Wallace (2007) found a curvilinear relationship with respect to age and perceived job insecurity. Parental Status indicates whether the respondent has a child living at home. Marital Status indicates whether the respondent is married or living with a partner. Adult-Care Responsibility indicates whether respondent has provided care for an adult relative for at least 3 hours per week in the past 6 months. Race indicates whether respondent is White, Asian, or Other (including Hispanic, Black, African-American, and More than One Race). We put Hispanic, Black, African-American, and those listing more than one race as a single category given their small sample size in this predominantly White and Asian workforce. College Graduate denotes whether the respondent has a college degree. Income is salary information from administrative data at the corporation. Tenure measures the length of time the worker has been employed for this corporation. Core Function captures workers’ work areas and is a dummy variable that identifies whether an employee’s work team is primarily involved in the core IT task of software development. Non-core teams provide support through project management, quality assurance and operations tasks. Therefore, Core Function controls for possible differences in workers’ perceived job insecurity given the structural location of their job within the corporation. Job Demands and Decision Authority are based on scales developed by Karasek and his colleagues (1998), measuring the demands and control one has over the job.

Manager Variables

Manager’s Gender distinguishes men (reference) and women managers. Manager’s Race/Ethnicity indicates whether an employee’s manager is White, Asian, or Other (including Hispanic/Black/African American/More than One Race, given small sample sizes). Manager’s Tenure identifies the length of time the manager has been employed at the firm. Manager’s Perceived Job Insecurity is a measure reported by the manager of how likely he or she will lose his or her job or be laid off in the next twelve months, from a scale of one to four, with one as “not at all likely” and four being “very likely.”

Analytic Strategy

Since we have data from both employees and their managers, we use multilevel ordered logistic regression models (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) to examine the association between managers’ characteristics and employees’ perceived job insecurity, simultaneously considering the fact that some workers were surveyed after the merger announcement. Multilevel models allow us to account for the clustering of employees working for the same manager, with 176 unique managers in this sample.ii Brant tests show that the parallel regression assumption is satisfied for the ordered logistic model (chi2(42) = 46.69, p = .286).iii The parallel regression assumption requires the relationship between each pair of outcome groups to be the same; for example, the coefficients that describe the relationship between lowest (perceived job insecurity being 1) versus all higher categories (perceived job insecurity being 2, 3, and 4) of the response variable are the same as those that describe the relationship between the next lowest (perceived job insecurity being 2) category and all higher categories (perceived job insecurity being 3 and 4). As robustness tests, we also estimated multilevel linear regression models (perceived job insecurity treated as a continuous rather than an ordinal variable) and multilevel logistic models (perceived job insecurity treated as a dichotomous variable, with those reported “likely” or “very likely” to be laid off coded as job insecure). We find similar results using all three approaches (not shown; available from authors).

Tests for multicollinearity find that most of the predictors are weakly correlated (correlation coefficient less than .2, available from authors). We obtained variance inflation factors (VIF) based on a single-level OLS model, given that there is currently no package providing VIFs for multilevel models. Except for age, all predictors have tolerance values well above .10, suggesting little risk of multicollinearity problems. We find that age is correlated with employees’ race and tenure, rather than the key variable of our interest – interview timing in reference to the merger announcement and manager’s characteristics. Therefore, we think our main findings are not biased by multicollinearity (tables with VIFs not shown; available from authors).

To test our first three hypotheses, we assess the extent to which employees’ perceived job insecurity is shaped by their managers’ characteristics and being surveyed after the merger announcement, net of employees’ own characteristics (Table 2, Model 1). To test our fourth hypothesis, we include a number of interaction terms (one at a time) between the merger announcement and manager characteristics in a model including both employee and manager characteristics (Table 2, Models 2 and 3). This allows us to test whether the relationships between characteristics of their managers and employees’ perceived job insecurity differ contingent on whether employees were interviewed before or after the merger announcement. Given that interaction terms may over- or under-estimate the true effects in models with categorical outcomes, our discussion focuses on differences in the predicted probabilities, which are not affected by group differences in unobserved heterogeneity (or residual variances) (Williams 2009). Analyses were conducted with STATA 11.

Table 2.

Multilevel Ordered Logistic Models of Individual and Manager Characteristics on Employees’ Job Insecurity, in Logged Odds

| VARIABLES | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merger knowledge | |||

| Employee interviewed post-merger announcement | 0.932*** | 1.695*** | −0.130 |

| (0.172) | (0.316) | (0.519) | |

| Employee characteristics | |||

| Female | −0.262 | −0.296 | −0.250 |

| (0.179) | (0.178) | (0.178) | |

| Age | 0.223* | 0.221* | 0.231* |

| (0.091) | (0.091) | (0.091) | |

| Age squared | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002* |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Married/Partnered | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.013 |

| (0.210) | (0.210) | (0.210) | |

| Parent | −0.013 | −0.015 | −0.023 |

| (0.176) | (0.176) | (0.176) | |

| Has adult care responsibility | 0.163 | 0.172 | 0.169 |

| (0.187) | (0.187) | (0.187) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | −0.056 | −0.107 | −0.066 |

| (0.225) | (0.224) | (0.224) | |

| Hispanic, Black or African American | 0.649* | 0.667* | 0.607* |

| (0.272) | (0.272) | (0.271) | |

| College graduate | −0.496* | −0.492* | −0.514* |

| (0.228) | (0.228) | (0.228) | |

| Logged income | −0.889 | −0.969* | −0.944* |

| (0.479) | (0.479) | (0.477) | |

| Tenure (years) | −0.012 | −0.014 | −0.012 |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Core function | −0.140 | −0.159 | −0.176 |

| (0.190) | (0.185) | (0.187) | |

| Decision authority | −0.410*** | −0.386*** | −0.413*** |

| (0.116) | (0.116) | (0.115) | |

| Job demands | 0.163 | 0.191 | 0.146 |

| (0.119) | (0.118) | (0.117) | |

| Manager characteristics | |||

| Female | 0.283 | 0.200 | 0.275 |

| (0.183) | (0.183) | (0.180) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | −0.540* | −0.508* | −0.509* |

| (0.232) | (0.229) | (0.230) | |

| Hispanic, Black or African American | −0.030 | 0.024 | −0.034 |

| (0.312) | (0.308) | (0.308) | |

| Manager’s tenure | −0.011 | 0.011 | −0.012 |

| (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.008) | |

| Manager’s job insecurity | 0.332** | 0.355** | 0.065 |

| (0.118) | (0.118) | (0.171) | |

| Interactions | |||

| Employee interviewed post-merger announcement* Manager’s tenure | −0.045** | ||

| (0.016) | |||

| Employee interviewed post-merger announcement* Manager’s job insecurity | 0.494* | ||

| (0.229) | |||

| Thresholds (see Note 1) | |||

| Cutpoint 1 | −7.139 | −7.512 | −8.201 |

| (5.301) | (5.288) | (5.288) | |

| Cutpoint 2 | −3.878 | −4.232 | −4.948 |

| (5.297) | (5.279) | (5.280) | |

| Cutpoint 3 | −1.695 | −2.041 | −2.750 |

| (5.302) | (5.281) | (5.280) | |

| Level 2 Pseudo R Squared (see Note 2) | 0.967 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Observations | 666 | 666 | 666 |

Notes:

These are the thresholds used to differentiate the adjacent levels of the response variable, job insecurity. For example, “cutpoint 1” is the estimated cutpoint used to differentiate those who report job insecurity to be 1 “not at all likely” to be laid off from those who report job insecurity to be 2 “not too likely” to be laid off. “Cutpoint 2” differentiates those who report job insecurity to be 2 “not too likely” to be laid off from those who report 3 “fairly likely” to be laid off, etc. Ordered logistic models assume that the categorical outcomes we observe in the data come from an underlying latent variable that is continuous. When values of the independent variables are evaluated at zero, the cutpoints are the estimated thresholds on the latent variable used to make the four groups that we observe with different levels of job insecurity (1, 2, 3, and 4). For example, the estimate of “cutpoint 1” in Model 1 indicates that respondents who had a value of −7.139 or less on the underlying latent variable that gives rise to the job insecurity variable would constitute the group who reported “not at all likely to lose jobs” (i.e., valued 1 for the outcome).

Pseudo R squared is defined as the ratio of two numbers. The numerator is the level-2 random effect difference between the current model and an unconditional model, and the denominator is the level-2 random effects of the unconditional model. The unconditional model is a null model including no covariate. See Raudenbush and Bryk (2002).

Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 describes the analytic sample of employees, as well as the two subgroups based on their knowledge of the merger. As noted above, 43% (286) of the employees in our sample were interviewed after the merger was announced. On average, employees were about 46 years old. Consistent with this age profile, most of the respondents are married or partnered (80%), with the majority of employees having children at home (56%), and about a quarter having adult care responsibilities (23%). Two in five (40%) respondents are women, and most (80%) have a college degree. The average salary of employees is high – $87,350 – as would be expected for technical professionals employed by a Fortune 500 firm. About seven in ten (67%) of the sample are White, 22% are Asian, and 11% are coded as Other (including Hispanic, Blacks/African Americans, and individuals reporting more than one race). Employees have an average tenure of about 13 years at this company. Slightly more than a third (37%) of the employees work in teams performing core IT functions. Employees report high levels of decision authority (3.83 out of 5) and job demands (3.59 out of 5). Approximately 34% employees reported that they were either “fairly likely” (= 3) or “very likely” (= 4) to be laid off over the next year. Turning to their managers’ characteristics, about 39% of the sample report to a woman manager. Managers’ average tenure at the corporation is quite high, at 16.75 years. Nineteen percent of employees’ managers reported they were “fairly likely” or “very likely” to be laid off in the next year. Most report to a White manager (75%), though almost one in five report to an Asian manager (17%).

Table 1.

Individual and Manager Characteristics

| Overall | Interviewed Before Merger Announcement | Interviewed After Merger Announcement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean/% | N | Mean/% | N | Mean/% | ||

| Merger knowledge | |||||||

| Employee interviewed post-merger announcement | 666 | 43% | 380 | – | 286 | – | |

| Employee characteristics | |||||||

| Female | 666 | 40% | 380 | 39% | 286 | 41% | |

| Age | 666 | 45.79 | 380 | 45.46 | 286 | 46.23 | |

| Married/Partnered | 666 | 80% | 380 | 80% | 286 | 80% | |

| Parent | 666 | 56% | 380 | 54% | 286 | 58% | |

| Has adult care responsibility | 666 | 23% | 380 | 20% | 286 | 26% | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 666 | 67% | 380 | 66% | 286 | 69% | |

| Asian | 666 | 22% | 380 | 21% | 286 | 24% | |

| Hispanic, Black or African American | 666 | 11% | 380 | 13% | 286 | 8% | * |

| College graduate | 666 | 80% | 380 | 81% | 286 | 79% | |

| Income | 666 | 87350.05 | 380 | 86426.89 | 286 | 88576.64 | |

| Tenure (years) | 666 | 13.37 | 380 | 13.14 | 286 | 13.68 | |

| Core function | 666 | 37% | 380 | 45% | 286 | 26% | *** |

| Decision authority | 666 | 3.83 | 380 | 3.81 | 286 | 3.86 | |

| Job demands | 666 | 3.59 | 380 | 3.63 | 286 | 3.52 | * |

| Employee job insecurity (likelihood of being fired or laid off) | 666 | 2.29 | 380 | 2.14 | 286 | 2.49 | *** |

| Employee job insecurity = 1 “not at all likely” | 666 | 11% | 380 | 14% | 286 | 6% | ** |

| Employee job insecurity = 2 “not too likely” | 666 | 56% | 380 | 61% | 286 | 49% | ** |

| Employee job insecurity = 3 “fairly likely” | 666 | 27% | 380 | 22% | 286 | 34% | *** |

| Employee job insecurity = 4 “very likely” | 666 | 7% | 380 | 3% | 286 | 11% | *** |

| Manager characteristics | |||||||

| Female | 666 | 39% | 380 | 37% | 286 | 43% | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 666 | 75% | 380 | 74% | 286 | 76% | |

| Asian | 666 | 17% | 380 | 18% | 286 | 16% | |

| Hispanic, Black or African American | 666 | 8% | 380 | 8% | 286 | 8% | |

| Manager’s tenure | 666 | 16.75 | 380 | 16.28 | 286 | 17.38 | |

| Manager’s job insecurity (likelihood of being fired or laid off) | 666 | 2.12 | 380 | 1.98 | 286 | 2.3 | *** |

| Manager’s job insecurity = 1 “not at all likely” | 666 | 14% | 380 | 17% | 286 | 9% | ** |

| Manager’s job insecurity = 2 “not too likely” | 666 | 67% | 380 | 72% | 286 | 62% | ** |

| Manager’s job insecurity = 3 “fairly likely” | 666 | 13% | 380 | 7% | 286 | 21% | *** |

| Manager’s job insecurity = 4 “very likely” | 666 | 6% | 380 | 4% | 286 | 9% | ** |

Note:

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05; test of significance based on t-tests

test of significance based on t-tests

We conducted t-tests to compare employees’ and manager’s characteristics for those interviewed prior to and those interviewed after the merger announcement (last column of Table 1). Echoing our consideration of the merger announcement as a natural experiment, the two groups are indistinguishable in terms of almost all characteristics, with a few exceptions. Those interviewed after the announcement are significantly more likely to report high levels of perceived job insecurity, that is, “fairly likely” or “very likely” to be laid off over the next year (45% vs. 25%, p < .001); the same holds for their managers’ perceived job insecurity levels (30% vs. 11%, p < .001). Employees interviewed before the announcement were, by happenstance, more likely to be Hispanic, Blacks/African Americans, and individuals reporting more than one race (13% vs. 8%, p < 0.05), in teams performing core IT functions (45% vs. 26%, p < .001) and correspondingly have slightly higher job demands (3.63 vs. 3.52, p < .05); accordingly, we control for these variables in the regression models.

Do Managers’ Characteristics Matter? (Hypothesis 1 and 2)

Results of the multilevel ordered logistic analysis estimating predictors of perceived job insecurity, including both individual and manager characteristics, are presented in Table 2.iv Before presenting specific results, we note that the unconditional intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for perceived job insecurity is .11 based on the multilevel linear model, or .13 based on the multilevel ordered logistic model. In other words, up to 13% of the variation in job insecurity is due to the fact that employees have different managers, highlighting the need to examine manager-related characteristics that potentially predict employees’ perceived job insecurity.

In additional analyses, we also included an interaction term between managers’ gender and employees’ gender to test whether different combinations of gender similarity or difference in the manager-employee dyad are associated with higher or lower employee perceived job insecurity. However, we found no effects of employee/manager gender similarity or difference (not shown; available from authors).

Turning to managers’ status characteristics – managers’ race – we find, contrary to our hypothesis, that employees reporting to Asian managers are more likely to report lower perceived job insecurity (−.540, p < .05) than those reporting to White managers. There is no statistically significant difference on employee perceived insecurity of reporting to Black, Hispanic or “Other” managers as compared to White managers. This finding suggests that the racial makeup of managers within the context of this one specific organization, within this specific industry, may play an important role in influencing the perceived job insecurity of workers reporting to them (Gorman and Kay 2010; Hirsh and Kornrich 2008). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012), Asians made up only 5 percent of all employed workers in 2011, but were 27% of software developers. Therefore, in contrast to other national-level studies showing Whites have lower perceived job insecurity than Hispanics and African Americans, on average (Wilson and Mossakowski 2012), we find, in this IT workforce, that having an Asian manager is related to lower perceived job insecurity. This finding highlights the importance of considering the racial composition of specific industries and workplaces. Asians are disproportionately concentrated in this industry and also well represented in the ranks of upper management in this division; employees’ status expectations may therefore lead them to feel protected by Asian managers, who are sometimes viewed as being well connected and benefiting from social networks within the firm. More generally, research should consider how the representation of certain groups in particular workforces and in top management ranks may affect employees’ sense of who has higher status and is more influential within a given organization. Historically, this has been White men, but that may no longer be the case in certain industries and organizations.

We also tested different combinations of the race of employees and the race of their managers, to understand whether racial similarity or difference in the manager-employee dyad is associated with higher or lower perceived job insecurity, finding this not to be the case (not shown, available from authors). Note, however, contrary to Hypothesis 1, we find no relationship between managers’ tenure, managers’ gender, and employees’ perceived job insecurity, controlling for employee characteristics.

As expected (see Hypothesis 2), we find that their managers’ own perceived job insecurity positively predicts employees’ perceived job insecurity (.332, p < .01), suggesting a crossover effect from managers to workers in perceived job insecurity. This adds to existing evidence showing that employees’ perceived insecurity crosses over to their spouses (Westman 2001; Wilson et al. 1993), and their children (Barling, Zacharatos and Hepburn 1999; Barling et al. 1998; Lim and Sng 2006; Zhao et al. 2012). The level-2 pseudo R-squared (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) of Model 1 is 96.7%, as compared with an unconditional model with no covariate; in other words, the team-level variance in employee job insecurity is reduced by 96.7% after including these manager characteristics.

Turning to employees’ own characteristics, we find the age-squared term is not significant, suggesting that the relationship between age and perceived job insecurity is linear instead of curvilinear, with older employees more likely to report higher levels of perceived job insecurity (.223, p < .05). Compared with White employees, Hispanic, Black, African American or “other” workers report higher perceived job insecurity (.649, p < .05). This is consistent with existing studies finding that Black and Hispanic workers tend to perceive employment as more precarious than Whites (Fullerton and Wallace 2007; Wilson et al. 2006; Wilson and Mossakowski 2012). Asian employees in this organization report similar levels of perceived job security as do White employees. Employees with a college degree report lower perceived job insecurity (−.496, p < .05). Further, although job demands are not related to employees’ perceived job insecurity, higher decision authority predicts lower perceived job insecurity (−.41, p < .001). We find no gender difference in perceived job insecurity. Neither do we find employees’ marital status, parental status, adult-care responsibilities, income, or tenure to be associated with their sense of job insecurity.

Does a Merger Announcement Accentuate Job Insecurity? (Hypothesis 3 and 4)

Turning to the indicator of whether or not employees were interviewed before or after the merger announcement, we find (not surprisingly) those who already knew about the merger when interviewed report greater perceived job insecurity. As shown in Model 1, and in support of Hypothesis 3, this predictor is strong, statistically significant, and in the positive direction. Consider two employees with the same background and work characteristics; the one who was interviewed after the merger announcement would have odds that are more than twice as high (= exp[.932] = 2.54, p < 0.001) to report a higher level of perceived job insecurity compared to one who was interviewed prior to the announcement.

After establishing that employees surveyed after the merger announcement report on average higher perceived job insecurity, we test whether status characteristics of their manager may be even more salient, such that employees reporting to higher status managers may feel more protected in the face of an impending merger. We do so by estimating regression models with interaction terms between each manager characteristic and the merger announcement, testing each interaction term one at a time.

Our analysis reveals that two specific manager characteristics (managers’ tenure and managers’ perceived job insecurity) are more closely related to workers’ perceived job insecurity among employees who knew about the upcoming merger than for those interviewed prior to the merger announcement (see interaction terms in Models 2 and 3 in Table 2). Specifically, neither managers’ tenure nor managers’ perceived job insecurity predict employees’ perceived job insecurity among those interviewed prior to the merger announcement (note that the non-significant main effect of manager tenure in Model 2 and the non-significant main effect of manager perceived job insecurity in Model 3 refer to employees who were interviewed prior to the announcement). For those interviewed after the announcement, managers’ tenure is negatively associated (−.045 + .011 = −.034, p < 0.01 based on a post-estimation test via the “lincom” command in Stata) while managers’ own perceived job insecurity is positively associated (.494 + .065 = .559, p < 0.001 based on a post-estimation test) with employees’ perceived job insecurity, respectively.v

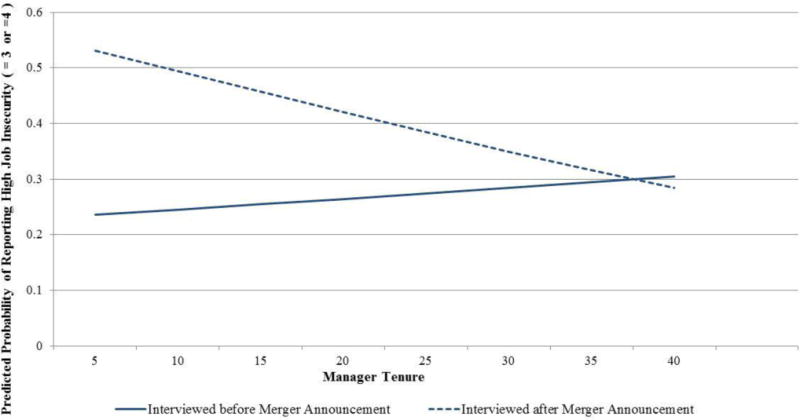

Figures 1 and 2 graph the relationships between being interviewed after the merger announcement, manager characteristics, and employees’ perceived job insecurity. Ordinal logistic models allow us to calculate probabilities for each level of the outcome (i.e., 1, 2, 3, and 4 for perceived job insecurity), but here for simplicity we only plot the marginal (population averaged) probability of employees reporting high levels of perceived job insecurity (“likely” or “very likely” to be laid off). Figure 1 shows that having managers with longer tenure is associated with employees’ lower probability of reporting high perceived job insecurity for those interviewed after the merger announcement but not those interviewed before the merger was announced. For example, a difference in manager tenure from 10 to 25 years would predict a 13-percentage-point lower probability of reporting high perceived job insecurity for employees interviewed after the merger announcement, whereas, for those interviewed before the announcement, their managers’ tenure has virtually no bearing on workers’ perceived job insecurity. This interaction suggests a buffering effect of working under a manager with more experience (and possibly better embedded and more powerful) in the firm, highlighting the potential significance of status expectations of managers with longer tenure, for employees’ perceived job insecurity under conditions of uncertainty (such as an impending merger).

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of Reporting High Job Insecurity by Manager Tenure, Before and After Merger Announcement

Note: Plotted here are marginal predicted probabilities, which are generated by the “gllapred marginal mu above()” syntax after a gllamm-estimated model. In addition. we used marginal effects at representative values (MERs) to get corresponding probabilities, that is. we leave the values of all other covariates as they are and only change the values of employees’ merger knowledge (0/1). managers’ tenure (5 to 40) and their interaction, and use the predicted mean across all respondents as the predicted probabilities.

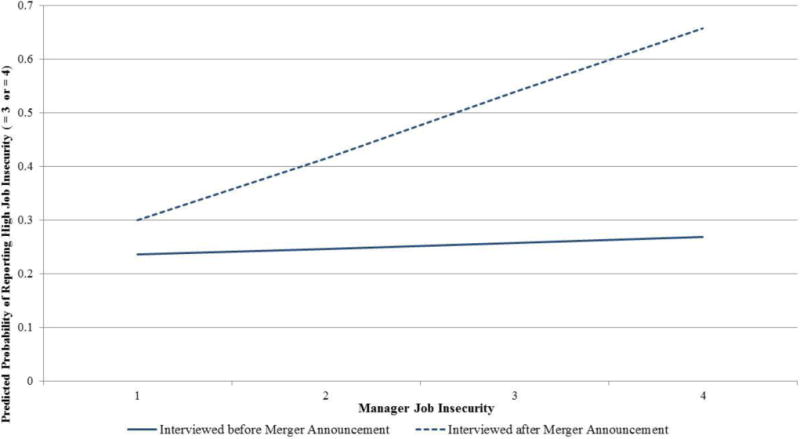

Figure 2.

Predicted Probability of Reporting High Job Insecurity by Manager Job Insecurity, Before and After Merger Announcement

Note: Plotted here are marginal predicted probabilities, which are generated by the “gllapred, marginal mu above()” syntax after a gllamm-estimated model. In addition, we used marginal effects at representative values (MERs) to get corresponding probabilities, that is, we leave the values of all other covariates as they are and only change the values of employees’ merger knowledge (0/1), managers’ job insecurity (1 to 4) and their interaction, and use the predicted mean across all respondents as the predicted probabilities.

Similarly, Figure 2 shows a virtually flat line for the relationship between managers’ and employees’ perceived job insecurity for those interviewed prior to the merger announcement, indicating that managers’ own perceived job insecurity is not related to employees’ perceived job insecurity when there is no knowledge of any impending threat to their employment. In contrast, for those surveyed after the merger announcement, their managers’ levels of perceived job insecurity are positively associated with employees’ own degree of perceived job insecurity. Recall that in the main effects models (see Model 1 of Table 2), managers’ perceived job insecurity is positively associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity. The interaction term highlights that managers’ perceived job insecurity is strongly associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity only for those aware of impending restructuring associated with a merger. Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of considering both the organizational climate and managers’ as well as employees’ characteristics in order to better understand employees’ psychosocial assessments, such as their sense of insecurity, regarding their jobs.

Discussion

The notion of lifelong, continuous employment is increasingly a remnant of the past, described as a false “career mystique” (Moen and Roehling 2005) that nevertheless continues to permeate organizational and governmental policies and practices, as well as individual expectations about stable work, job security, and a steady stream of income. But research shows a steady upward trend in subjective job insecurity (see Fullerton and Wallace 2007), even as perceived job insecurity has been linked to lower levels of employee health and well-being (Burgard, Brand and House 2009; Ferrie et al. 2005; László et al. 2010). These trends and impacts highlight the importance of understanding the multilayered contexts of contemporary insecurity among even advantaged workers, such as those working in IT jobs.

Moving beyond existing research, we have considered multilevel effects of both the organizational climate and managers’ characteristics, over and above employees’ own characteristics. To do so we draw on theories of status expectations and crossover to hypothesize and test whether managers’ characteristics and sense of job insecurity shape the sense of job insecurity of the employees reporting to them.

We find that, in contrast to Hypothesis 1, net of individual characteristics, neither managers’ gender nor their tenure within the organization is associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity. But as hypothesized, their managers’ race/ethnicity is associated with employees’ perceived job insecurity. However, contrary to Hypothesis 1, it is those employees who have an Asian rather than a White manager who tend to report less perceived job insecurity, suggesting that cognitive attributions by employees of status in an IT workforce may favor Asian over White managers. Future research should test whether in IT environments it is Asians who possess greater status, thereby being perceived as better able to protect the jobs of those working under them. The unique racial demographics of the information technology industry, which has a disproportionately higher percentage of Asians, points to the need to think about and theorize race in work organization contexts that move beyond the White/non-White dichotomy.

We find support for Hypothesis 2, in that working for managers who have high perceived job insecurity magnifies employees’ own sense of insecurity. This follows from crossover theory, suggesting that managers’ assessments of their own perceived job insecurity crosses over to shape employees’ own sense of perceived job insecurity. This finding suggests the need for future longitudinal studies assessing the nature and direction of changes in both managers’ and employees’ sense of insecurity as well as other appraisals of their situations.

This study serendipitously provided the opportunity to examine perceived job insecurity in the context of an unexpected merger announcement. We take advantage of the fact that a merger was announced in the middle of data collection, using the announcement as a demarcation of two climates at this one corporation. The fact that some employees were surveyed prior to and some after the merger announcement provided two very different organizational climates: one of relative stability and another more precarious, colored by the uncertainty of what a merger may mean in terms of layoffs. Not surprisingly, in support of Hypothesis 3, those who knew about the merger announcement when interviewed reported considerably higher levels of perceived job insecurity. We also find support for Hypothesis 4, such that manager characteristics (specifically having long tenure) and managers’ assessments of their job security serve to moderate the effects on employees’ perceived job insecurity of the uncertainty generated by concerns about the forthcoming merger. We find evidence of a buffering effect, in that employees who knew about the merger (i.e., employees who were interviewed after the announcement was made) who worked under managers with long tenure were more likely to have lower perceived job insecurity; in contrast, for employees interviewed before the merger announcement, we find no relationship between managers’ tenure and employees’ perceived job insecurity. This may reflect the greater salience of status expectations in an uncertain climate, with employees assessing long tenured managers as having greater status, and thus possibly able to protect their teams in the face of the merger. But there is also evidence of an intensification effect of working for managers who are worried about losing their own jobs. Specifically, the positive crossover relationship linking managers’ perceived job insecurity with that of their employees’ perceived job insecurity appears to be the case only in a climate of uncertainty (for those surveyed after the merger announcement as compared to those who were unaware of the upcoming merger). This points to a fertile future research agenda incorporating layers of context – in this case managers’ characteristics and working in a climate of uncertainty. The contribution of this study lies in our moving beyond individualistic models of job insecurity to incorporate contextual and organizational factors as well. We also extend the implications of the theoretical framework on status expectations, by highlighting that status expectations may not be static, but contingent on contexts that may be continually evolving. This is shown in our findings, in the shifting importance of different manager characteristics that signal status, leading to differences in employee insecurity. We find that having an Asian manager may signal higher status in this specific organization and IT workforce, while having a manager with longer tenure may be more salient in light of an impending organizational change, providing an example of changing status markers as the context changes.

There are several important limitations, however. First, the merger announcement occurred within a broader context of a global economic crisis touching both the local and the larger national economy. In analysis not reported here, we have adjusted for unemployment rates at national, state, and local levels and found similar results (not shown; available from authors). While other studies have pointed to important differences across national contexts in the shaping of perceived job insecurity, what we contribute here is to highlight the importance as well of the meso contexts of teams and organizational climates. A second limitation is that we are limited to a single, one-item measure of perceived job insecurity. However, this is a common measure of perceived job insecurity. And in analysis not shown we have also tried dichotomizing the outcome, finding similar results (not shown; available from authors). A third limitation is the fact that the sample is of a specific workforce, and hence we are unable to speak to the generalizability of the findings. Yet, we believe the implications of our findings are important in establishing empirically the role of managers in predicting employees’ perceived job insecurity, theorizing the importance of employees’ status expectations of their managers (as gauged by managers’ characteristics). Note that we cannot make any causal claims, given the cross sectional nature of our data. However, the conclusions we draw are on the basis of regressions that are consistent with what theory would predict.

Given the nature of contemporary work experience, losing a job may also not be as important as being able to reclaim a similar one. However, a t-test shows that in contrast to perceived job insecurity, workers’ reported employability (encompassing workers’ skill sets and knowledge) is not sensitive to the announcement of the merger (not shown; available from authors). That is, while employees’ perceived likelihood of losing their job differs by when they were surveyed as related to the merger announcement as expected, their reported likelihood of finding a similar job does not relate to the merger announcement. We also test employability as a dependent variable in regression models, finding that in contrast to perceived job insecurity, none of the manager characteristics predicts worker employability once controlling for workers’ individual characteristics (not shown; available from authors).

Uncertainty increasingly characterizes the contemporary global economy, making both organizational restructuring and employee perceived job insecurity key issues for policy and practice as well as for future research. The findings reported here are important, in that they locate employees’ psychosocial assessments within the context of their experiences on the job, in this case defined by their managers’ own relative status and managers’ own sense of perceived insecurity.

Front-line managers are often depicted as the interpreters of the larger organization to their direct reports. What our findings suggest is that employees interpret their own situations based on their status expectations about their managers, especially under conditions of uncertainty. Having a manager with long tenure and job security serves to predict employees’ own sense of security. Working for a high status manager (in this environment a manager who is Asian) also reduces employees’ perceptions of their job insecurity. This points to the need for additional research on the multilayered contexts of employment that serve to define the situations and stresses of employees, as well as ways to mitigate the uncertainty and insecurity associated with the restructuring that is increasingly common in today’s unsettled economic climate.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the Work, Family and Health Network (www.WorkFamilyHealthNetwork.org), which is funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant # U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (Grant # U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Science Sciences Research, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant # U01OH008788, U01HD059773). Grants from the William T. Grant Foundation, Alfred P Sloan Foundation, and the Administration for Children and Families have provided additional funding. The author gratefully acknowledge support from the Minnesota Population Center (5R24HD041023) funded through grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices. Special acknowledgement goes to Extramural Staff Science Collaborator, Rosalind Berkowitz King, Ph.D. and Lynne Casper, Ph.D. for design of the original Workplace, Family, Health and Well-Being Network Initiative.

Footnotes

We did not use multiple imputation because it is not supported by “gllamm” in Stata as of the writing of this paper. In addition, an examination of the missing pattern suggests that 71% of the missing cases (110 out of 156) are due to managers’ not answering the survey. In other words, the majority of missing cases are due to non-participation on the manager’s end rather than employees’ selective answering of questions. Therefore, we do not impute manager characteristics given that we have no information on these managers. Another 17 employees do not report their job insecurity level, for whom we feel multiple imputation is not a good choice given the danger of imputing dependent variables. For the remaining 29 cases, they are missing due to employee’s income (10 out of 29), manager’s job insecurity level (9 out of 29), manager’s gender (6 out of 29), or employee’s job demands (4 out of 29).

As suggested by one reviewer, we also experimented with a random-slope model. No convergence was achieved, however, suggesting no significant variance in the slopes across team-level units.

Brant tests are based on single-level models; no multilevel version exists as of the writing of this paper.

Ordered logistic models assume that the categorical outcomes we observe in the data come from an underlying latent variable that is continuous. When values of the independent variables are evaluated at zero, the cutpoints are the estimated thresholds on the latent variable used to make the four groups that we observe with different levels of job insecurity (1, 2, 3, and 4). For example, the estimate of “cutpoint 1” in Model 1 indicates that respondents who had a value of −7.139 or less on the underlying latent variable would constitute the group who reported “not at all likely to lose jobs” (i.e., valued 1 for the outcome). In general, these estimated cutpoints are not used in the interpretation of the results. See Long (1997) for a discussion.

As pointed out by a reviewer, significant interaction terms in categorical models could be due to either “true” significance or unequal residual variances across groups. Following the reviewer’s suggestion, we estimated heterogeneous choice models via the “oglm” command in Stata with robust standard errors clustered at the manager level. The interaction term between merger knowledge and manager’s tenure remains significant (p = .007), while that between merger knowledge and manager’s job insecurity is no longer so. However, no estimate from the variance part of the heterogeneous choice model is significant, suggesting no evidence of unequal residual variance across groups as constructed by managers’ tenure or employees’ merger knowledge, raising doubts about the need for heterogeneous choice models in our case.

References

- Baron James N, Bielby William T. Bringing the Firms Back In: Stratification, Segmentation, and the Organization of Work. American Sociological Review. 1980;45:737–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker Arnold B, Westman Mina, van Emmerik IJ Hetty. Advancements in Crossover Theory. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2009;26(3):206–219. [Google Scholar]

- Barling Julian, Dupre Kathryne E, Hepburn C Gail. Effects of Parents’ Job Insecurity on Children’s Work Beliefs and Attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1998;83(1):112–118. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barling Julian, Zacharatos Anthea, Hepburn C Gail. Parents’ Job Insecurity Affects Children’s Academic Performance through Cognitive Difficulties. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1999;84(3):437–444. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Ella J, Nkomo Stella M. Our Separate Ways: Black and White Women and the Struggle for Professional Identity. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Joseph, Fisek M Hamit, Norman Robert Z, Zelditch Morris., Jr . Status Characteristics and Social Interaction: An Expectation-States Approach. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Blair-Loy Mary, Wharton Amy. Employees’ Use of Work-Family Policies and the Workplace Social Context. Social Forces. 2002;80:813–845. [Google Scholar]

- Bray Jeremy W, Kelly Erin L, Hammer Leslie B, Almeida David M, Dearing James W, King Rosalind B, Buxton Orfeu. An Integrative, Multilevel, and Transdisciplinary Research Approach to Challenges of Work, Family, and Health. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press; 2013. (RTI Press publication No MR-0024-1303). Retrieved May 27, 2014 ( http://www.rti.org/publications/rtipress.cfm?pubid=20777) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe Forrest, Kellogg Katherine. The Initial Assignment Effect: Local Employer Practices and Positive Career Outcomes for Work-Family Program Users. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:291–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2011. Washington D.C: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2013 ( http://www.bls.gov/cps/demographics.htm#race) [Google Scholar]

- Burgard Sarah A, Brand Jennie E, House James S. Perceived Job Insecurity and Worker Health in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(5):777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard Sarah A, Kalousova Lucie, Seefeldt Kristin S. Perceived Job Insecurity and Health: The Michigan Recession and Recovery Study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54(9):1101–1106. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182677dad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Dawn S, Ferguson Merideth, Kacmar K Michele, Grzywacz Joseph G, Whitten Dwayne. Pay It Forward: The Positive Crossover Effects of Supervisor Work-Family Enrichment. Journal of Management. 2011;37(3):770–789. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla Emilio J. Bringing Managers Back In: Managerial Influences on Workplace Inequality. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:667–694. [Google Scholar]

- De Cuyper Nele, De Witte Hans, Elst Tinne Vander, Handaja Yasmin. Objective Threat of Unemployment and Situational Uncertainty during a Restructuring: Associations with Perceived Job Insecurity and Strain. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2010;25(1):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dencker John. Corporate Restructuring and Sex Differences in Managerial Promotion. American Sociological Review. 2008;73:455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Elman Cheryl, O’Rand Angela. Perceived Job Insecurity and Entry into Work-Related Education and Training among Adult Workers. Social Science Research. 2002;31:49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Elvira Marta M, Zatzick Christopher D. Who’s Displaced First? The Role of Race in Layoff Decisions. Industrial Relations. 2002;41(2):329–361. [Google Scholar]

- Farber Henry S. Employment Insecurity: The Decline in Worker-Firm Attachment in the United States. Department of Economics and Industrial Relations Section, Princeton University; 2008. (Working Paper 530). Retrieved May 27, 2014 ( http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp019k41zd50q) [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Roberto M. Skill-Biased Technological Change and Wage Inequality: Evidence from a Plant Retooling. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;107(2):273–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie Jane E, Shipley Martin J, Newman Katherine, Stansfeld Stephen A, Marmot Michael. Self-Reported Job Insecurity and Health in the Whitehall II Study: Potential Explanations of the Relationship. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(7):1593–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie Jane E, Shipley Martin J, Marmot Michael, Stansfeld Stephen A, Smith George D. The Health Effects of Major Organisational Change and Job Insecurity. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;46(2):243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton Andrew S, Anderson Kathryn Freeman. The Role of Job Insecurity in Explanations of Racial Health Inequalities. Sociological Forum. 2013;28(2):308–325. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton Andrew S, Wallace Michael E. Traversing the Flexible Turn: US Workers’ Perceptions of Job Security, 1977–2002. Social Science Research. 2007;36(1):201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Glavin Paul. The Impact of Job Insecurity and Job Degradation on the Sense of Personal Control. Work and Occupations. 2013;40(2):115–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman Elizabeth H, Kay Fiona M. Racial and Ethnic Minority Representation in Large U.S. Law Firms. Studies in Law, Politics, and Society, Special Issue: Law Firms, Legal Culture, and Legal Practice. 2010;52:211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Green Francis, Felstead Alan, Burchell Brendan. Job Insecurity and the Difficulty of Regaining Employment: An Empirical Study of Unemployment Expectations. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 2000;62:857–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren Johnny, Sverke Magnus. Does Job Insecurity Lead to Impaired Well-Being or Vice Versa? Estimation of Cross-Lagged Effects using Latent Variable Modeling. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2003;24(2):215–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh C Elizabeth, Kornrich Sabino. The Context of Discrimination: Workplace Conditions, Institutional Environments, and Sex and Race Discrimination Charges. American Journal of Sociology. 2008;113(5):1394–1432. doi: 10.1086/525510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollister Matissa N. Employer and Occupational Instability in Two Cohorts of the National Longitudinal Surveys. The Sociological Quarterly. 2012;53(2):238–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kalev Alexandra. How You Downsize is Who You Downsize: Biased Formalization, Accountability and Managerial Diversity. American Sociological Review. 2014;79(1):109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition. American Sociological Review. 2009;74(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek Robert, Brisson Chantal, Kawakami Norito, Houtman Irene, Bongers Paulien, Amick Benjamin. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An Instrument for Internationally Comparative Assessments of Psychosocial Job Characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1998;3(4):322–355. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King Rosalind B, Karuntzos Georgia, Casper Lynne M, Moen Phyllis, Davis Kelly D, Berkman Lisa, Durham Mary, Kossek Ellen Ernst. Work-Family Balance Issues and Work-Leave Policies. In: Gatchel RJ, Schultz IZ, editors. Handbook of Occupational Health and Wellness. New York City: Springer Science and Business Media; 2012. pp. 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimaki Mika, Vahtera Jussi, Pentti Jaana, Ferrie Jane E. Factors Underlying the Effect of Organisational Downsizing on Health of Employees: Longitudinal Cohort Study. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:971–975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimaki Mika, Vahtera Jussi, Ferrie Jane E, Hemingway Harry, Pentti Jaana. Organisational Downsizing and Musculoskeletal Problems in Employees: A Prospective Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2001;58:811–817. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.12.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klandermans Bert, van Vuuren Tinka. Job Insecurity: Introduction. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 1999;8(2):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lam Jack, Fan Wen, Moen Phyllis. Is Insecurity Worse for Well-being in Turbulent Times? Mental Health in Context. Society and Mental Health. 2014;4(1):55–73. doi: 10.1177/2156869313507288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- László Krisztina D, Pikhart Hynek, Kopp Maria S, Bobak Martin, Pajak Andrzej, Malyutina Sofia, Salavecz Gyongyver, Marmot Michael. Job Insecurity and Health: A Study of 16 European Countries. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(6):867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Vivien KG, Sng Qing Si. Does Parental Job Insecurity Matter? Money Anxiety, Money Motives, and Work Motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(5):1078–1087. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Scott J. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall Ruby, Kalil Ariel, Spindel Laurel J, Hart Cassandra. Job Loss at Mid-life: Managers and Executives Face the “New Risk Economy”. Social Forces. 2008;87(1):185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Moen Phyllis, Roehling Patricia. The Career Mystique: Cracks in the American Dream. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Newman Katherine S. Falling from Grace: Downward Mobility in the Age of Affluence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Susan Y, Roscigno Vincent J. Discrimination, Women, and Work: Processes and Variations by Race and Class. The Sociological Quarterly. 2009;50(2):336–359. [Google Scholar]

- Probst Tahira M. Job insecurity: Implications for Occupational Health and Safety. In: Antoniou A, Cooper C, editors. New Directions in Organizational Psychology and Behavioral Medicine. Farnham, UK: Gower; 2011. pp. 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Probst Tahira M, Brubaker Ty L. The Effects of Job Insecurity on Employee Safety Outcomes: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Explorations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2001;6(2):139–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Stephen W, Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway Cecilia L. Why Status Matters for Inequality. American Sociological Review. 2014;79(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway Cecilia L. Gender, Status, and Leadership. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57(4):637–655. [Google Scholar]

- Roth Louise M. The Social Psychology of Tokenism: Status and Homophily Processes on Wall Street. Sociological Perspectives. 2004;47(2):189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Selenko Eva, Mäkikangas Anne, Mauno Saija, Kinnunen Ulla. How Does Job Insecurity Relate to Self-reported Job Performance? Analysing Curvilinear Associations in a Longitudinal Sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2013;86(4):522–42. [Google Scholar]

- Swaen Gerand MH, Bültmann Ute, Kant IJmert, van Amelsvoort Ludovic GPM. Effects of Job Insecurity from a Workplace Closure Threat on Fatigue and Psychological Distress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2004;46(5):443–449. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000126024.14847.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westman Mina, Etzion Dalia. Crossover of Stress, Strain and Resources from One Spouse to Another. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1995;16:169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Westman Mina, Etzion Dalia, Danon Esti. Job Insecurity and Crossover of Burnout in Married Couples. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2001;22(5):467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Westman Mina. Stress and Strain Crossover. Human Relations. 2001;54(6):717–751. [Google Scholar]

- Williams Richard. Using Heterogeneous Choice Models to Compare Logit and Probit Coefficients across Groups. Sociological Methods and Research. 2009;37:531–559. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson George, Eitle Tamela M, Bishin Benjamin. The Determinants of Racial Disparities in Perceived Job Insecurity: A Test of Three Perspectives. Sociological Inquiry. 2006;76:210–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson George, Mossakowski Krysia. Job Authority and Perceptions of Job Security: The Nexus by Race among Men. American Behavioral Scientist. 2012;56(11):1509–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Stephen M, Larson Jeffrey H, Stone Katherine L. Stress among Job Insecure Workers and their Spouses. Family Relations. 1993;42(1):74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Xiuxi, Lim Vivien, Teo Thompson. The Long Arm of Job Insecurity: Its Impact on Career-Specific Parenting Behaviors and Youths’ Career Self-Efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012;80(3):619–628. [Google Scholar]