Abstract

Objective:

To examine the extent to which abused and neglected children perpetrate three different types of violence within and outside the home: criminal, child abuse, and intimate partner violence and determine whether childhood maltreatment leads to an increased risk for poly-violence perpetration.

Method:

Using data from a prospective cohort design study, children (ages 0-11) with documented histories of physical and sexual abuse and/or neglect (n = 676) were matched with children without such histories (n = 520) and assessed in young adulthood (average age 29). Official criminal records in conjunction with self-report data were used to assess violent outcomes.

Results:

Compared to the control group, individuals with histories of child abuse and/or neglect were significantly more likely to be poly-violence perpetrators, perpetrating violence in all three domains (relative risk = 1.26). All forms of childhood maltreatment (physical and sexual abuse and neglect) significantly predicted poly-violence perpetration.

Conclusions:

These findings expand the cycle of violence literature by combining the distinct literatures on criminal violence, child abuse, and partner violence to call attention to the phenomenon of poly-violence perpetration by maltreated children. Future research should examine the characteristics of maltreated children who become poly-violence perpetrators and mechanisms that lead to these outcomes.

Keywords: Child abuse and neglect, intergenerational transmission, domestic violence, criminal violence, poly-violence perpetration, cycle of violence

The perpetration of violence both inside and outside the home is a serious public health concern in the United States. Between 2010 and 2011, approximately 7.6 million people were violently victimized and about 1.1 million people were victimized by intimate partners (National Crime Victimization Survey, 2012). During fiscal year 2011, approximately 680,000 children were victims of maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). This study seeks to examine the extent to which individuals with documented histories of child abuse and neglect perpetrate these three forms of violence.

Although child abuse and neglect are thought to increase risk for criminal violence, child abuse/neglect, and intimate partner violence, social scientists have primarily studied violence between family members as a separate phenomenon from criminal violence (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Sheidow, & Henry, 2001). While there is an increasing literature on criminal offenders who specialize in one type of crime versus those who commit multiple types of offenses (e.g. Pullman & Seto, 2012; Tumminello, Edling, Lilijeros, Mantegna, & Sarnecki, 2013; Wanklyn, Ward, Cormier, Day, & Newman, 2012), this work focuses on criminal offending in general and does not necessarily distinguish between family and criminal violence. To our knowledge, no study has examined the effects of child maltreatment on the intersection of various types of violent outcomes both within and outside the family sphere. This paper examines the extent to which individuals with a history of child abuse and neglect commit violent acts across various domains and targets, rather than specializing in one type, and focuses on perpetration of violence inside and outside the home.

Literature Review

Several theories have been offered to explain the “cycle of violence”, or the phenomenon whereby child abuse and/or neglect increases risk for criminal violence as well as perpetration of maltreatment toward the next generation. Adaptations of Bandura’s (1973) social learning theory posit that physically abused children adopt the violent behavior patterns they experience from their parents through parental modeling and observational learning. According to social-processing theory, the physically abused child fails to attend to appropriate social cues or misinterprets them by attributing hostile intentions to others and generally conceptualizes the world as an aggressive and violent place (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990). From a sociological perspective, Agnew’s (1992) social-psychological strain theory suggests that overwhelming negative emotions such as anger, frustration, and resentment resulting from abusive treatment from others can result in violent and criminal behavior. Developmental psychologists have argued that individuals who experience the stigmatization of sexual abuse may avoid the negative state of shame by displacing it with anger and aggression, which may then lead to violent behaviors (Feiring, Taska, & Lewis, 1998; Negrao, Bonanno, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, 2005).

Criminal violence

A number of prospective studies have found support for the link between childhood maltreatment and future perpetration of criminal violence (Herrenkohl, Egolf, & Herrenkohl, 1997; Lansford, Miller-Johnson, Berlin, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2007; Salzinger, Rosario, & Feldman, 2007; Smith & Thornberry, 1995; Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Homish, & Wei, 2001; Topitzes, Mersky, & Reynolds, 2012; Widom, 1989d). On the other hand, some research has yielded contradictory results (Gutierres & Reich, 1981; Zingraff, Leiter, Myers, & Johnsen, 1993). Research on the cycle of violence indicates that it is not exclusively physical abuse (experiencing violence as a child) that increases a child’s risk for subsequent violence. Individuals who were neglected as children are as likely to be arrested for violence in adulthood as children with histories of physical abuse (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Mersky & Reynolds, 2007; Widom, 1989b). Furthermore, a small number of studies have found a link between childhood sexual abuse and violent behavior (Herrera & McCloskey, 2003; Sidebotham, Golding, & ALSC Study Team, 2001; Siegel & Williams, 2003x).

With some exceptions (Topitzes et al., 2012; Widom, 1989d), most of the literature on the intergenerational transmission of violence focuses on the perpetration of violence by delinquents and adolescents. This is not only likely to underestimate rates of transmission, but also to obscure discontinuities in the trajectory of violent behavior such as desistance or adult onset violence (Topitzes et al., 2012). For example, just six years after the initial assessment of the relationship between child maltreatment and violence, Maxfield and Widom (1996) found that rates of violent arrests of individuals who were abused and neglected in childhood more than doubled from adolescence (8.5%) to adulthood (18%).

The assessment of violent behavior often depends on both official data sources (e.g. juvenile and adult court and arrest records) and self-report data, which measures unsubstantiated behaviors (Herrenkohl, et al., 1997; Lansford et al., 2007; Salzinger et al., 2007; Smith & Thornberry, 1995). There may be potential biases in retrospective self-report measures of violence, such as social desirability factors, recall bias, and loss of information that may influence rates of violent behavior. On the other hand, sole reliance on official data may also be problematic since official measures of violent crime typically undercount violent behavior (MacDonald, 2002). In 2011, only about half of violent victimizations were reported to the authorities (National Crime Victimization Survey, 2012). Furthermore, biases in police and court processing of cases (based on prior abuse history, gender, and race) may have an impact on official records (Farrington, 1998; Williams & Herrera, 2007). Limiting the measurement of violence to only one of these data sources provides a less than comprehensive assessment of violence (Topitzes et al., 2012).

Childhood maltreatment

Several scholarly reviews have concluded that the case for the intergenerational transmission of child abuse may be overstated (Falshaw, Browne, & Hollin, 1997; Ertem, Leventhal, & Dobbs, 2000;Thornberry, Knight, & Lovegrove, 2012; Widom, 1989c). Thornberry and colleagues (2012) identified 11 methodological criteria necessary for assessing the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment and found that the strongest studies only met six [with one exception, Widom (1989a)]. While some prospective studies found support for the intergenerational transmission of child abuse (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011; Dixon, Browne, & Hamilton-Giachritsis, 2005; Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Thompson, 2006; Thornberry, 2009), others found no evidence linking childhood abuse with abuse of the next generation (Altemeir, O’Connor, Sherrod, Tucker, & Vietze, 1986; Renner & Slack, 2006; Sidebotham et al., 2001; Widom, 1989a). Sidebotham and colleagues (2001) found that only maternal sexual abuse was significantly related to perpetration of maltreatment, while Renner and Slack (2006) found that only mother’s childhood physical maltreatment increased the likelihood of “leaving a child at risk of harm.” However, follow-up periods were often short (Berlin et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2005; Sidebotham et al., 2001; Thompson, 2006), and this small window of possible exposure very likely underestimates the prevalence of maltreatment.

Another methodological problem is that these studies vary in the use of different and inconsistent criteria for childhood abuse and neglect as the independent and dependent variables. Some studies utilize official records to determine perpetration of child abuse (the outcome), while using retrospective self-reports to measure a parent’s past victimization (Berlin et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2005; Renner & Slack, 2006; Sidebotham et al., 2001; Thompson, 2006). Two prospective studies relied solely on self-report data (Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Renner & Slack, 2006). Studies based on retrospective accounts of a person’s maltreatment, especially those with long recall periods, are open to a number of potential biases such as risk of distortion, loss of information, repression of memories and social desirability factors (Thornberry et al., 2012; Widom, 1989c). Furthermore, this tendency to work backwards from a population of abusive parents to their childhood histories may lead to an inflated rate of transmission because maltreated individuals who did not grow up to be abusive parents are not represented (Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Widom, 1989c). Only two studies to date have used substantiated official records to measure parent’s experience of childhood abuse (Thornberry, 2009; Widom 1989a).

Intimate partner violence

Another form of the cycle of violence theory posits that childhood maltreatment leads to subsequent perpetration of intimate partner violence. Although a large body of literature has reported an association between observing marital violence in childhood and perpetrating intimate partner violence or being victimized by a romantic partner (e.g. Mihalic & Elliot, 1997; Simons, Wu, Johnson, & Conger, 1995; Stith, Rosen, Middleton, Busch, Lundenberg, & Carlton, 2000), fewer studies have assessed the link between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence. Some prospective studies have reported findings supporting this connection (Ehrensaft, Cohen, Brown, Smailes, Chen, & Johnson, 2003; Herrenkohl, Mason, Kosterman, Lengua, Hawkins, & Abbott, 2004; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998; White & Widom, 2003). However, one prospective study using the Rochester Youth Development data did not find that physical abuse in adolescence predicted perpetration of intimate partner violence in early adulthood (Ireland & Smith, 2009). Methodological limitations noted earlier apply to this literature as well, with most studies relying on self-report measures to assess both childhood maltreatment and later intimate partner violence (Herrenkohl et al., 2004; Magdol et al., 1998).

The Current Study

The present study was designed to examine whether maltreated children are at increased risk to perpetrate violence across three different contexts - criminal violence, child abuse, and intimate partner violence – in later life. We label this group of people poly-violence perpetrators (PVP) and suggest that these individuals may be the most problematic, given that they are exhibiting violence in all three major domains of their lives. Although past work with this dataset has examined numerous aspects of the cycle of violence, this is the first prospective examination of poly-violence perpetration with this dataset.

The present study has several methodological advantages. First, the prospective longitudinal design of this study allows for determination of the correct temporal sequence of all three types of violent outcomes. Second, the long-term follow-up in this study allows for an examination of violent outcomes into adulthood, whereas most studies are limited to short follow-up periods. Third, cases of past childhood abuse and/or neglect were obtained through official records and therefore minimize the problems and potential biases associated with reliance on retrospective self-reports. Fourth, outcome measures of perpetration of criminal violence and perpetration of child abuse utilized both self-report and official data to minimize problems with reliance on only one source of information, so that concerns about under-reporting and lack of detection are minimized. Fifth, we utilized a matched control group to assess the magnitude of relationships between childhood abuse/neglect and later violent behavior. Finally, we include prevalence data for both maltreated and non-maltreated groups in our analyses.

This study represent the experiences of children growing up in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the Midwest part of the United States and may raise concerns about the relevance of these cases to current cases. However, the cases studied here are quite similar to current cases being processed by the child protection system and the courts. One difference is that these children were not provided with extensive services or treatment options as are available today and, thereby, the results of this study represent the natural history of the development of abused and neglected children.

We have two major hypotheses. (1) Individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and/or neglect will be more likely to perpetrate violence in each of three domains –criminal violence, child abuse, and intimate partner violence – as compared to a group of matched controls. (2) Individuals who were abused and/or neglected as children will be more likely to be poly-violence perpetrators, compared to matched controls, and this increase in risk for PVP will be manifest for each type of childhood maltreatment studied here – physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect.

Method

Design and Participants

The data used here are from a large research project based on a prospective cohort design (Leventhal, 1982; Schulsinger, Mednick, & Knop, 1981) study in which abused and/or neglected children were matched with non-abused and non-neglected children and followed prospectively into young adulthood (Widom, 1989a). The cohort design involves the assumption that the major difference between the abused and neglected and comparison group is in the abuse or neglect experience. Since it is not possible to randomly assign subjects to groups, the assumption of equivalency for the groups is an approximation.

Abuse and neglect cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971. The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court-substantiated cases of child abuse and neglect were included. To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality, and to ensure that the temporal sequence was clear (that is, child abuse and neglect → subsequent outcomes), abuse and neglect cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Excluded from the sample were court cases that represented: (1) adoption of the child as an infant; (2) “involuntary” neglect only -- usually resulting from the temporary institutionalization of the legal guardian; (3) placement only; or (4) failure to pay child support.

A comparison group of children who did not have documented cases of abuse and/or neglect was established, with matching on the basis of sex, age, race, and approximate family socio-economic status during the time period under study (1967 through 1971). Matching for social class was important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences (Adler, Boyce, Chesney, Cohen, Folkman, Kahn, & Syme, 1994; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Conroy, Sandel, & Zuckerman, 2010; Widom, 1989d). It is difficult to match exactly for social class because higher income families could live in lower social class neighborhoods and vice versa. When random sampling is not possible, Shadish, Cook and Campbell (2002) recommend using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes. The matching procedure used here is based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. Similar procedures, with neighborhood school matches, were used in studies of people with schizophrenia (Watt, 1972) to match approximately for social class. Busing was not operational at the time, and students in elementary schools in this county were from small, socio-economically homogeneous neighborhoods.

Children who were under school age at the time of the abuse and/or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 1 week), and hospital of birth through the use of county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 6 months), and class in elementary school during the years 1967-1971. Overall, there were matches for 74% of the abused and neglected children.

Official records were checked and any proposed comparison group child who had an official record of child abuse or neglect (n = 11) was eliminated and a replacement child was substituted. The number of individuals in the control group who were actually abused, but not reported, is unknown. The control group may also differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables associated with abuse or neglect.

The first phase of this research began as a prospective cohort design study based on an archival records check to identify a group of abused and neglected children and matched controls and conduct a criminal history search to assess the extent of delinquency, crime, and violence (Widom, 1989a). The second phase of the research involved tracing, locating, and interviewing the abused and/or neglected individuals (22 years after the initial court cases for the abuse and/or neglect) and the matched comparison group. Follow-up in-person interviews conducted during 1989-1995 were approximately 2-3 hours long and consisted of standardized tests and measures.

Of the 1,575 persons in the original sample, 1,307 subjects (83%) were located and 1,196 interviewed (76%) during 1989-1995. Of the people not interviewed, 43 were deceased (prior to interview), 8 were incapable of being interviewed, 268 were not found, and 60 refused to participate. There were no significant differences between the follow-up sample (N = 1,196) and the original sample (N = 1,575) in terms of demographic characteristics (male, White, poverty in childhood census tract, or current age) or group status (abuse/neglect versus comparison group). The sample was an average of 29.2 years old (range = 19.0 – 40.7; S.D. = 3.8) and included 582 females (49%). Based on self-reports of race/ethnicity, 61% of participants were White, non-Hispanic, 33% African American, 4% Hispanic, 1.5% American Indian, and less than 1% Pacific Islander or other. The median occupational level (Hollingshead, 1975) for the group was semi-skilled workers, and only 13% held professional jobs. The highest level of school completed for the sample was mean = 11.5 years (SD = 2.2). Thus, the sample contains very few individuals at the higher end of the socio-economic spectrum and the bulk of the sample is at the lower end.

Procedures

Respondents were interviewed in person usually in their homes, or, if the respondent preferred, another place appropriate for the interview. The interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group, and to the participants' group membership. Similarly, the subjects were blind to the purpose of the study. Subjects were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study and subjects who participated signed a consent form acknowledging that they understood the conditions of their participation and that they were participating voluntarily. For those individuals with limited reading ability, the consent form was read to the person and, if necessary, explained verbally.

Measures and Variables

Child abuse and neglect

Childhood physical and sexual abuse and neglect were assessed through review of official records processed during the years 1967 to 1971. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, bone and skull fractures, and other evidence of physical injury. Sexual abuse charges varied from felony sexual assault to fondling or touching in an obscene manner, rape, sodomy, and incest. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents' deficiencies in childcare were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time. These cases represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children. Although the cases for most of the children in this sample involved only one type of abuse or neglect, approximately 10% of the abused and neglected group had experienced more than one type. In addition, although the child maltreatment literature recognizes psychological maltreatment as an important type of childhood abuse (Hart, Brassard & Karlson, 1996), the cases studied here were processed during the late 1960s and early 1970s when psychological maltreatment was not recognized as a distinct form and, thus, it is not included here.

Criminal violence

Criminal violence is based on three indicators using official arrest records and self-report data. Official records from three levels of law enforcement (local, state, and federal) agencies were searched for arrests during 1987-1988 (Widom, 1989b) and again in 1994 (Maxfield & Widom, 1996). Complete criminal histories were obtained for the participants through 1994 when they were mean age 32. Official arrests refer to any arrest for a violent crime, including robbery, assault, assault and battery, battery, battery with injury, aggravated assault, involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide, murder and attempted murder, rape, sodomy, and robbery and burglary with injury. Eight items from the Self-report of Behaviors (Wolfgang & Weiner, 1989) were used as a measure of self-reported violence and asked participants whether they had engaged in any of these behaviors before or after the age of 18 (e.g., “Have you ever shot someone; attacked someone with the purpose of killing him/her; used physical force to get money, drugs, or something else from someone?). An additional indicator of self-reported violence was based on seven items from the Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) module of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule revised (DIS-III-R) (Robins, Helzer, Cottler, & Goldring, 1989). These seven self-report items referred to behavior towards others before or after the age of 15 (e.g., “Have you been in more than one fight that came to swapping blows [other than fights with your partner]?”). Official records and self-reports were combined to create a dichotomous measure of criminal violence, where the presence of either an arrest or any self-report of violence was coded 1 and the absence of any arrest or self-report was coded 0.

Child abuse

Perpetration of child abuse was also measured using both official arrest records and self-report data. Official arrest records refer to the presence/absence of any arrests for child abuse. The self-report measure is based on participants’ responses to one item from the Antisocial Personality Disorder module of the DIS-III-R (Robins et al., 1989): “Have you ever spanked or hit a child, hard enough so that he or she had bruises or had to stay in bed or see a doctor?” These two items were grouped to form an overall dichotomous measure of perpetration of child abuse, where 0 = no child abuse and 1 = any arrest or self-report of child abuse.

Intimate partner violence (IPV)

IPV is based on participants’ responses to one item from the Antisocial Personality Disorder module of the DIS-III-R (Robins et al., 1989): “Have you ever hit or thrown things at your partner?” and this refers to current or past romantic partners.

Poly-violence perpetration (PVP)

PVP is defined as having an official arrest record or a self-report of perpetration of violent behavior in more than one domain (criminal violence, child abuse, or intimate partner violence). PVP is treated as an ordinal variable, where no violence = 0, violence in one domain = 1, violence in two domains = 2, and violence in all 3 domains = 3.

Control variables

Age at the first interview (1989-1995), gender, and race/ethnicity were included as control variables. Race/ethnicity was coded 1 for White, non-Hispanics and 0 for Blacks, Hispanics and other non-Whites. Gender was coded 1 for females and 0 for males.

Data Analysis

Logistic regression was used to determine the relationship between the independent variable (childhood maltreatment) and dichotomous indicators of criminal violence, child abuse, and intimate partner violence (the dependent variables). Because rates of different types of violence vary by demographic characteristics (Cunradi, Caetano, & Schaefer, 2002; Thompson, 2006), all analyses controlled for age, sex, and race. Thus, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. In order to utilize as many participants as possible, analyses do not use matched pairs only. Prior examinations of matched and unmatched samples from this dataset have found no differences in results (Widom, 1989d; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007). In order to determine whether child abuse and neglect predicted poly-violence perpetration, a Poisson regression analysis was conducted. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and SPSS version 18.0.2 was used for all analyses.

Results

Child Abuse and Neglect and Perpetration of Three Types of Violence

Table 1 presents basic statistics and results of logistic regressions on the extent to which individuals with histories of child abuse and neglect perpetrate criminal violence, child abuse, and IPV compared to matched controls. The table is organized by type of violence, with criminal violence at the top, child abuse in the middle, and IPV in the bottom portion. Adjusted odds ratios are reported with controls for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. As hypothesized, the top portion of the table shows that individuals with documented histories of abuse and neglect were significantly more likely to have an arrest for violence (AOR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.16-2.23, p = .004) and significantly more likely to self-report violent behavior (AOR = 1.55, 95% CI = .977-2.04, p = .000) than matched controls. Similarly, the middle portion of the table shows that individuals with documented histories of abuse and neglect were significantly more likely to have an arrest for child abuse (AOR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.08-5.46, p = .033) and significantly more likely to self-report child abuse behavior (AOR = 1.61, 95% CI = 1.41-6.27, p = .004) than matched controls. Finally, the last portion of the table shows that individuals with documented histories of abuse and neglect were significantly more likely to self-report intimate partner violence (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.08-5.46, p = .001) than matched controls.

Table 1.

Perpetration of Criminal Violence, Child Abuse, and Neglect

| Total | Abuse/Neglect | Control | AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N | 1196 | 676 | 520 | ||

| Criminal Violence | |||||

| Criminal Violence Arrest |

18.6 | 21.0 | 15.6 | 1.60** | 1.16-2.23 |

| Criminal Violence Self-report |

59.4 | 63.2 | 54.4 | 1.55*** | 0.98-2.04 |

| Any Criminal Violence Arrest or Self-report |

62.7 | 66.6 | 57.7 | 1.61*** | 1.25-2.06 |

| Child Abuse | |||||

| Child Abuse Arrest |

2.7 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 2.43* | 1.08-5.46 |

| Child Abuse Self-report |

3.6 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 2.97** | 1.41-6.27 |

| Any Child Abuse Arrest or Self- report |

6.2 | 8.4 | 3.3 | 2.72*** | 1.56-4.74 |

| Intimate Partner Violence | |||||

| Intimate Partner Violence Self-report |

38.4 | 42.5 | 33.1 | 1.54*** | 1.10-1.97 |

Note: Prevalence rates reflect adjusted mean rates; Logistic regression, AOR = adjusted odds ratios with controls for age, sex, and race; CI = confidence interval.

p < .05,

p < 01,

p < .001.

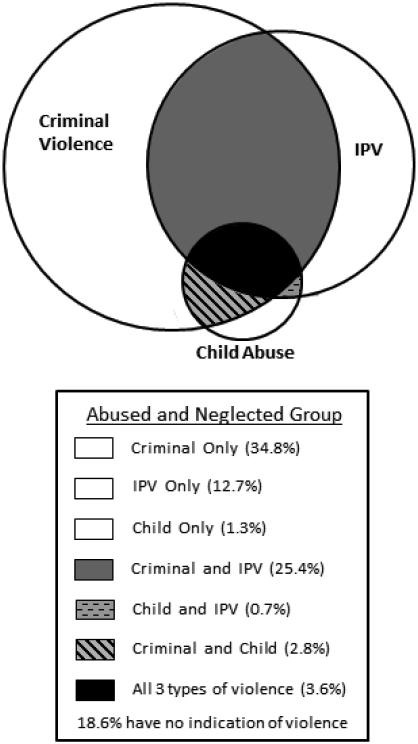

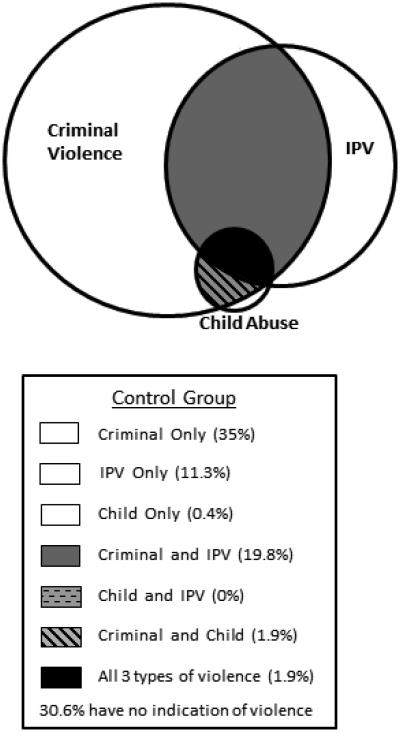

Child Abuse and Neglect and Poly-Violence-Perpetration

Table 2 shows the results of Poisson regression analyses predicting PVP by overall childhood abuse and/or neglect and by the specific types of child maltreatment (physical and sexual abuse and neglect), controlling for age, sex, and race. The results indicate that individuals with histories of childhood abuse and/or neglect (32.5%) had higher rates of perpetrating violence in multiple domains than controls (22.7%), (RR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.12-1.41, p =.000). Compared to the control group, 40.6% of individuals with histories of childhood sexual abuse (RR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.14-1.73, p =.007), 33% of individuals with histories of physical abuse (RR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.07-1.58, p = .001), and 31% of individuals with histories of neglect (RR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.08-1.37, p = .001) were all at higher risk for perpetration of violence in two or more domains. Venn diagrams (Figures 1A and 1B) show the overlap in the perpetration of violence across these multiple domains for the abused and/or neglected group and controls separately (the scales of the two Venn diagrams are equivalent). Surprisingly, only a small percentage of both the abused and/or neglected group (3.6%) and controls (1.9%) perpetrated violence in all three spheres.

Table 2.

Poisson Regression Predicting Poly-Violence Perpetration by Child Abuse and Neglect Overall and by Specific Type of Abuse or Neglect

| Parameter | Estimate (SE) |

χ 2 | Exp (B) |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Abuse/Neglect | .228 (.058) | 15.63 | 1.26*** | 1.12-1.41 |

| Intercept | −.445 (.224) | 3.95 | 0.64 | 0.41-0.99 |

| Age | .014 (.007) | 3.48 | 1.01 | 0.10-1.03 |

| Race (White Non-Hispanic) | −.005 (.057) | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.89-1.11 |

| Gender (Female) | −.040 (.056) | 0.51 | 0.96 | 0.86-1.07 |

| Physical Abuse | .265 (.099) | 7.21 | 1.30** | 1.07-1.58 |

| Intercept | −.275 (.314) | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.41-1.40 |

| Age | .011 (.100) | 1.16 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 |

| Race (White Non-Hispanic) | −.099 (.083) | 1.41 | 0.91 | 0.77-1.07 |

| Gender (Female) | −.126 (.082) | 2.39 | 0.88 | 0.75-1.03 |

| Sexual Abuse | .339 (.105) | 10.35 | 1.40*** | 1.14-1.73 |

| Intercept | −.328 (.324) | 1.02 | 0.72 | 0.38-1.36 |

| Age | .013 (.011) | 1.45 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.04 |

| Race (White Non-Hispanic) | −.106 (.083) | 1.64 | 0.90 | 0.77-1.06 |

| Gender (Female) | −.115 (.085) | 1.85 | 0.89 | 0.76-1.05 |

| Neglect | .195 (.061) | 10.30 | 1.22*** | 1.08-1.37 |

| Intercept | −.320 (.240) | 1.78 | 0.73 | 0.45-1.16 |

| Age | .010 (.008) | 1.47 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 |

| Race (White Non-Hispanic) | −.005 (.062) | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.88-1.12 |

| Gender (Female) | −.044 (.061) | 0.54 | 0.96 | 0.85-1.08 |

Note: SE = Standard Error; Exp (B) = Relative risk ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

* p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Figure 1A. Abused and Neglected Group.

Figure 1A shows the extent of overlap in types of violent outcomes for individuals with documented histories of child abuse and neglect.

Figure 1B. Control Group.

Figure 1B shows the overlap in type of violent outcomes for individuals without documented histories of child abuse and neglect (the control group).

Discussion

Using a prospective cohort design with documented cases of childhood abuse and neglect, the present study examined whether childhood maltreatment predicted subsequent perpetration of violence in three different domains. Our findings are consistent with a large body of research linking child maltreatment to later perpetration of criminal violence, child abuse, and intimate partner violence (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Magdol et al., 1998; Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Smith & Thornberry, 1995; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2001; Thornberry, 2009). However, the current analysis has expanded our understanding of this issue by showing that individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse/neglect were significantly more likely to be poly-violence perpetrators than individuals without such histories.

Individuals who were maltreated in childhood were almost twice as likely as matched controls to perpetrate criminal violent behavior. Although the prevalence rate we report here appears rather high (more than 60% of maltreated individuals either self-report violence or had a violent arrest), it is comparable to rates ranging 50-70% in other studies that have included self-reports to assess violent outcomes (Smith & Thornberry, 1995; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2001). Official arrests accounted for only about 30% of the total violent behavior for both the maltreated group and the controls. This highlights the importance of using multiple methods in assessing violent outcomes in an effort to get a more complete picture of the range of violent behavior.

We also found that individuals with histories of childhood abuse and/or neglect were almost three times more likely than matched controls to perpetrate child abuse. About 8% of individuals with histories of childhood maltreatment self-reported or had an official arrest for child abuse. These findings provide support for the intergenerational transmission of violence theory and, as suggested by an anonymous reviewer, help tilt the weight of the mixed evidence in the existing maltreatment literature. Although our combined self-report and official arrest measure of child abuse is more comprehensive than previous individual assessments, the rates of child abuse perpetration in our sample are still considerably lower than would have been expected. It is likely that these findings are limited in their ability to capture the full extent of child abuse perpetration. Perpetration of child abuse was assessed during interviews when participants were mean age 29, an age at which some of the participants may not have had children. Thus, it is possible that a higher prevalence of child abuse would manifest itself later in adulthood. Furthermore, it is very likely that child abuse arrests dramatically undercount rates of perpetration, since maltreatment is typically handled by referral to the Child Protection Services (CPS) or a similar social service agency (Thornberry et al., 2012). These findings should be replicated with an older sample and one with access to self-reports as well as CPS records.

Individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect were also more likely than matched controls to report perpetration of intimate partner violence. However, it is important to note that we measured a relatively non-serious type of IPV, hitting or throwing objects, using a single item. Thus, our results may not capture the entire extent of the IPV construct and may not be generalizable to other and more serious forms of IPV. In addition, as this measure relied exclusively on self-reports, there is no way to confirm the IPV behavior. It would be helpful to have other information about perpetration of IPV from orders of protection or court records.

Consistent with our main hypothesis, our results showed that individuals with histories of child abuse/neglect were more likely to be poly-violence perpetrators as compared to the control group. However, it was surprising to find that only 3.6% of abused and neglected individuals were perpetrators in all three violence domains. This may be due to the low prevalence of child abuse, particularly since the overlap between perpetration of criminal violence and intimate partner violence was quite high. However, over 70% of individuals with histories of childhood abuse and neglect who did perpetrate child abuse were also violent in other domains. Future research with more comprehensive measures of child abuse might find a larger overlap between perpetration of child abuse and perpetration of violence in different domains and a higher prevalence of individuals who perpetrate violence in all three domains.

Our results also indicated that the three types of child abuse measured here (physical and sexual abuse and neglect) independently predicted PVP. Although an extensive literature has focused on the link between physical abuse and subsequent violence, some literature has reported a connection between neglect and, to a lesser extent, sexual abuse and violent behavior (Herrera & McCloskey, 2003; Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Mersky & Reynolds, 2007). These new findings provide evidence that individuals with histories of neglect and sexual abuse, in addition to physical abuse, are at risk to be poly-violence perpetrators.

Although the roots of violence may begin during childhood in the home, our results demonstrate that the impact of early childhood maltreatment on perpetration of violence is not confined to the family sphere. For individuals with child abuse/neglect histories, criminal violence was more frequent than child abuse and intimate partner violence combined. Interestingly, the majority of individuals who perpetrated child abuse and intimate partner violence also perpetrated criminal violence, while the reverse was not true. Only about half of the individuals who perpetrated criminal violence also perpetrated within family violence. This suggests that there may be different pathways from child abuse and neglect to poly-violence perpetration and criminal violence perpetration.

Although there is little previous research that examines the study of criminal and family violence together in the context of childhood maltreatment in particular, there are a number of studies examining men who are generally violent – those who perpetrated both criminal violence and intimate partner violence (Gorman-Smith et al., 2001; Klevens, Simon, & Chen, 2012; Boyle, O’Leary, Rosenbaum, & Hassett-Walker, 2007). While these studies were not prospective or longitudinal and did not include control groups, their findings provide insight into poly-violence perpetrators. According to these studies, these poly-violent men directed about the same level of violence at all targets, whether familial or non-familial, were involved in the most violence, held the most favorable attitudes towards the use of violence, and more frequently found violence a justifiable response. These earlier findings suggest that PVP may represent a general interpersonal strategy for these individuals. In the context of maltreatment, PVP may reflect the intergenerational transmission of a more general orientation towards violent behavior in interactions with others rather than specific modeled behaviors. On the other hand, given the reported co-occurrence of domestic violence and child abuse, it is also possible that the individuals in the present sample were exposed to parental violence not recorded at the time.

Another important finding is that the cycle of violence is not inevitable. Close to 30% of the maltreated group did not perpetrate any types of violence. Numerous studies have reported other negative consequences of childhood maltreatment, including depression, withdrawal, or more extreme behavior such as suicide (Cichetti, Rogosch, Lynch, & Holt, 1993; Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb, & Janson, 2009; Kaplan, Pelcovitz, & Labruna, 1999; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007). However, there is increasing attention to potential protective factors that may buffer against the negative effects of childhood maltreatment (Affi & MacMillan, 2011; Klika & Herrenkohl, 2013; Topitzes, Mersky, Dezen, & Reynolds, 2013).

Limitations

Despite the numerous strengths of the current study, several caveats are worth noting. The findings of the current study are based on cases of childhood abuse and neglect drawn from official court records and, thus, most likely represent the most extreme cases processed in the system (Groeneveld & Giovannoni, 1977). This means that these findings are not generalizable to unreported or unsubstantiated cases of child abuse and neglect (Widom, 1989d). Because this sample is composed predominantly of children from families at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, these findings also cannot necessarily be generalized to abuse and neglect that occurs in middle- or upper- class children and their families. It is also possible that using court cases confounds the experience of abuse with the experience of court involvement. However, in many cases, the child victim was not removed from the home or placed in foster care or treated. This was especially true for cases of physical and sexual abuse that were processed in the adult criminal courts. Finally, the results of the present study should be interpreted as applicable to individuals whose maltreatment occurred during childhood. It is possible that children maltreated at a later time, such as during adolescence, may manifest different consequences.

Research Implications

Our findings expand the current cycle of violence literature to include an examination of perpetration of violence within and outside the home and raise a number of questions about the relationship between childhood maltreatment and poly-violence perpetration. Future research should examine differences between maltreated individuals who commit PVP compared to those who may specialize in one domain to determine whether there are different transmission mechanisms operating for these individuals. For example, men who are poly-violent perpetrators have been found to use more illegal drugs, be more impulsive, and manifest an overall deviant lifestyle compared to “family only” violent men (Boyle et al., 2007; Cogan & Ballinger, 2006). Finally, it would be interesting to examine whether there are differences between individuals who are poly-violence perpetrators in the family context only (child abuse and IPV) versus those who are violent outside the home in the criminal domain.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Treatment strategies and interventions implemented to stop the continuation of the cycle of violence often focus on violent offenders who perpetrate violence in specific domains (i.e., sex offenders, abusive parents, or criminally violent individuals). The current findings suggest that researchers, clinicians, and policymakers should consider identifying poly-violence perpetrators when implementing interventions, since these individuals may be the most problematic given their violent behavior in multiple situations with multiple targets. It is very possible that these PVP may be accounting for higher rates of program failures and recidivism across the different types of violent offender groups as well as potentially depleting public resources. Therefore, interventions may need to screen and target PVP rather than targeting specific violent behaviors in isolation.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported in part by grants from NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033 and 89-IJ-CX-0007), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Points of view are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the United States Department of Justice.

References

- Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist. 1994;49(1):15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL. Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;56(5):266–272. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–87. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeier WA, O'Connor S, Sherrod KB, Tucker D, Vietze P. Outcome of abuse during childhood among pregnant low income women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1986;10(3):319–330. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(86)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: A social learning analysis. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82(1):162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DJ, O’Leary KD, Rosenbaum A, Hassett-Walker C. Differentiating between generally and partner-only violent subgroups: Lifetime antisocial behavior, family of origin violence, and impulsivity. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23(1):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Lynch M, Holt KD. Resilience in maltreated children: Processes leading to adaptive outcome. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:629–629. [Google Scholar]

- Cogan R, Ballinger BC. Alcohol problems and the differentiation of partner, stranger, and general violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(7):924–935. doi: 10.1177/0886260506289177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy K, Sandel M, Zuckerman B. Poverty grown up: How childhood socioeconomic status impacts adult health. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31:154–160. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c21a1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17(4):377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Browne K, Hamilton-Giachritsis C. Risk factors of parents abused as children: A mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (part 1) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2005;46(1):47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertem IO, Leventhal JM, Dobbs S. Intergenerational continuity of childhood physical abuse: How good is the evidence? Lancet. 2000;356(9232):814–819. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falshaw L, Browne KD, Hollin CR. Victim to offender: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;1(4):389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington D. Predictors, causes, and correlates of male youth violence. In: Tonry M, Moore MH, editors. Youth violence. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1998. pp. 421–475. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M. The role of shame and attributional style in children's and adolescents' adaptation to sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3(2):129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Sheidow AJ, Henry DB. Partner violence and street violence among urban adolescents: Do the same family factors relate? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(3):273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld LP, Giovannoni JM. Disposition of child abuse and neglect cases. Social Work Research and Abstracts. 1977;13:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierres S,E, Reich J,W. A developmental perspective on runaway behavior: Its relationship to child abuse. Child Welfare. 1981;60:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SN, Brassard MR, Karlson HC. Psychological maltreatment. In: Briere J, Berliner L, Bulkley JA, Jenny C, Reid T, editors. The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. pp. 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl RC, Egolf BP, Herrenkohl EC. Preschool antecedents of adolescent assaultive behavior: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(3):422–432. doi: 10.1037/h0080244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Mason WA, Kosterman R, Lengua LJ, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD. Pathways from physical childhood abuse to partner violence in young adulthood. Violence and Victims. 2004;19(2):123–136. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.2.123.64099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera VM, McCloskey LA. Sexual abuse, family violence, and female delinquency: Findings from a longitudinal study. Violence and Victims. 2003;18(3):319–334. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland TO, Smith CA. Living in partner-violent families: Developmental links to antisocial behavior and relationship violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(3):323–339. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: A review of the past 10 years. Part I: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1214–1222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Simon TR, Chen J. Are the perpetrators of violence one and the same? Exploring the co-occurrence of perpetration of physical aggression in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(10):1987–2002. doi: 10.1177/0886260511431441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klika JB, Herrenkohl TI. A review of developmental research on resilience in maltreated children. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2013;14(3):222–234. doi: 10.1177/1524838013487808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:233–245. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM. Research strategies and methodologic standards in studies of risk factors for child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1982;6:113–123. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(82)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JM. The effectiveness of community policing in reducing urban violence. Crime & Delinquency. 2002;48(4):592–618. [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(3):375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: Revisited six years later. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky J, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and violent delinquency: Disentangling main effects and subgroup effects. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:246–258. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SW, Elliott D. A social learning theory model of marital violence. Journal of Family Violence. 1997;12(1):21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Negrao C, Bonanno GA, Noll JG, Putnam FW, Trickett PK. Shame, humiliation, and childhood sexual abuse: Distinct contributions and emotional coherence. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(4):350–363. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: a two-generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(11):1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullman L, Seto MC. Assessment and treatment of adolescent sexual offenders: Implications of recent research on generalist versus specialist explanations. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36(3):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner LM, Slack KS. Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Understanding intra-and intergenerational connections. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30(6):599–617. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler LB, Goldring E. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Washington University; St. Louis, MO: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger S, Rosario M, Feldman RS. Physical child abuse and adolescent violent delinquency: The mediating and moderating roles of personal relationships. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):208–219. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulsinger F, Mednick SA, Knop J. Longitudinal research, methods and uses in behavioral science: Methods and uses in behavioral science. Kluwer; Boston, MA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental design for generalized causal inference. Houghton-Mifflin; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sidebotham P, Golding J, ALSC Study Team Child maltreatment in the "children of the nineties". A longitudinal study of parental risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(9):1177–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JA, Williams LM. The relationship between child sexual abuse and female delinquency and crime: A prospective study. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2003;40(1):71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Wu CI, Johnson C, Conger RD. A test of various perspectives on the intergenerational transmission of domestic violence. Criminology. 1995;33(1):141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Thornberry TP. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology. 1995;33(4):451–481. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, Carlton RP. The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(3):640–654. [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Homish DL, Wei E. Maltreatment of boys and the development of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. Exploring the link between maternal history of childhood victimization and child risk of maltreatment. Journal of Trauma Practice. 2006;5:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP. The apple doesn't fall far from the tree (or does it?): Intergenerational patterns of antisocial behavior—the American Society of Criminology 2008 Sutherland Address. Criminology. 2009;47(2):297–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove PJ. Does maltreatment beget maltreatment? A systematic review of the intergenerational literature. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2012;13(3):135–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838012447697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topitzes J, Mersky JP, Dezen KA, Reynolds AJ. Adult resilience among maltreated children: A prospective investigation of main effect and mediating models. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(6):937–949. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topitzes J, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. From child maltreatment to violent offending an examination of mixed-gender and gender-specific models. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(12):2322–2347. doi: 10.1177/0886260511433510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumminello M, Edling C, Liljeros F, Mantegna RN, Sarnecki J. The phenomenology of specialization of criminal suspects. PloS One. 2013;8(5):e64703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau Child Maltreatment. 20122011 Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics Criminal Victimization. 20122011 Available from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv11.pdf.

- Wanklyn SG, Ward AK, Cormier NS, Day DM, Newman JE. Can we distinguish juvenile violent sex offenders, violent non-sex offenders, and versatile violent sex offenders based on childhood risk factors? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(11):2128–2143. doi: 10.1177/0886260511432153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt NF. Longitudinal changes in the social behavior of children hospitalized for schizophrenia as adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1972;155:42–54. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Widom CS. Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: The mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility, and alcohol problems. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(4):332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989a;59(3):355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and violent criminal behavior. Criminology. 1989b;27:251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1989c;106(1):3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989d;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Herrera VM. Child maltreatment and adolescent violence: Understanding complex connections. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):203–207. doi: 10.1177/1077559507304427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang ME, Weiner N. Unpublished interview protocol: University of Pennsylvania Greater Philadelphia Area Study. University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff MT, Leiter J, Myers KA, Johnsen M. Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology. 1993;31(2):173–202. [Google Scholar]