Abstract

Several decades of research have demonstrated that marital relationships have a powerful influence on physical health. However, surprisingly little is known about how marriage affects health—both in terms of psychological processes and biological ones. We investigated the associations between perceived partner responsiveness—the extent to which people feel understood, cared for and appreciated by their romantic partner—and diurnal cortisol over a 10-year period in a large sample of married and cohabitating couples in the U.S. Partner responsiveness predicted higher wakeup cortisol values and steeper (“healthier”) cortisol slopes at the 10-year follow-up, and these associations remained strong after controlling for demographic factors, depressive symptoms, agreeableness, and other positive and negative relationship factors. Further, declines in negative affect over the 10-year period mediated the prospective association between responsiveness and cortisol slope. These findings suggest that diurnal cortisol may be a key biological pathway through which social relationships impact long-term health.

Keywords: perceived partner responsiveness, social relationships, cortisol, health, marriage, MIDUS

Twenty-five years ago, House and colleagues demonstrated that stronger social ties are associated with lower levels of mortality (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). Since then, there has been a groundswell of research on the links between social relationships and health. Most recently, a meta-analysis of 148 studies showed a 50% increased likelihood of survival for those with better social relationships (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Yet a critical question remains: How do social relationships “get under the skin” to impact health and longevity, both from a psychological perspective and a biological one?

A recent meta-analysis of the links between marital quality and health showed robust associations between how happy people are in their marriage and how physically healthy they are (Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2014). However, that meta-analysis also revealed how little is known about the specific aspects of marriage that matter most for physical health—positive aspects (e.g., warmth, understanding), negative aspects (e.g., conflict, hostility), or both. It has been argued that one of the keys to satisfying and lasting romantic relationships is the extent to which people believe that their partners understand, validate and care for them—termed perceived partner responsiveness (Reis, 2012). Partner responsiveness is a strong predictor of satisfaction and intimacy in relationships, including when couples are coping with breast cancer (Manne, et al., 2004), discussing personal goals (Feeney, 2004), and when they share positive events with each other (Gable, Gonzaga, & Strachman, 2006). It has been argued that partner responsiveness is an organizing principle in the study of relationships because it shares common elements with many important relationship constructs, providing core validation of the self, and leading to feelings of warmth, acceptance, belonging, and trust (Reis, 2012).

Partner responsiveness also appears to have relevance for health. For instance, among patients undergoing knee surgery, partner responsiveness during recovery predicted fewer knee limitations 3 months later (Khan, et al., 2009). Recently, it was shown that perceived partner responsiveness interacted with social support to predict longevity in a large sample of married and cohabitating couples from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study (Selcuk & Ong, 2013). We propose that a critical pathway through which perceived partner responsiveness positively impacts health and longevity is through its effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and its hormonal product, cortisol.

The HPA axis has attracted substantial attention from researchers interested in the links between social relationships and health due to its sensitivity to psychological factors and its potent effects on multiple biological systems (Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007). The biological reach of cortisol is extensive, with glucocorticoid receptors present in virtually every cell of the human body. Cortisol plays an important role in facilitating learning, memory, and emotion in the central nervous system, regulates gluconeogenesis in the metabolic system (particularly in times of threat, e.g., the fight- or-flight response), and helps regulate the immune system.

Cortisol production has a diurnal rhythm, with levels typically rising in the first 30 minutes after a person wakes, then decreasing over the day to its low point shortly before bedtime. A growing body of evidence suggests that a flatter diurnal cortisol slope is a predictor of poorer physical health, including Type II diabetes status (Hackett, Steptoe, & Kumari, 2014), pre-clinical atherosclerosis (Hajat, et al., 2013), and mortality (Kumari, Shipley, Stafford, & Kivimaki, 2011). In both childhood and adulthood, negative aspects of social relationships (e.g., interpersonal conflict) are linked to flatter diurnal cortisol slopes, whereas better relationship quality is linked to steeper slopes (Saxbe, Repetti, & Nishina, 2008; Slatcher & Robles,2012). It has been theorized that the nature of the early social environment, particularly the degree to which it is nurturing or aversive, can lead to HPA dysregulation in young adulthood and beyond (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011). But the extent to which long-term HPA function is shaped by social relationships that are formed in adulthood remains unknown.

Virtually no studies have longitudinally investigated the potential psychological pathways through which romantic relationships impact health and health-related biological processes (e.g., cortisol) over an extended period of time. However, psychological processes—particularly affective ones—figure prominently in theoretical models that link marital quality and health (Robles, et al., 2014; Slatcher, 2010), with negative affect being inversely associated with relationship quality (Gottman, 1998) and physical health (Krantz & McCeney, 2002) and positive affect being positively associated with relationship quality (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005) and physical health (Pressman & Cohen, 2005). In line with these models, a recent study demonstrated that perceived partner responsiveness prospectively predicted positive and negative affect, along with other indicators of psychological well-being, in married individuals (Selcuk, Gunaydin, & Ong, 2014). Prior research also has shown that negative affect is associated with less healthy diurnal cortisol profiles (Polk, Cohen, Doyle, Skoner, & Kirschbaum, 2005), whereas positive affect is associated with healthier diurnal cortisol profiles (Ong, Fuller-Rowell, Bonanno, & Almeida, 2011). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that perceived partner responsiveness would prospectively predict steeper cortisol slopes, and would do so, at least in part, through lower negative affect and higher positive affect assessed at follow-up.

We investigated the prospective associations between perceived partner responsiveness and diurnal cortisol over a 10-year period in a large sample of married and cohabitating couples in the U.S., controlling for partner responsiveness at the 10 year follow-up, as well as age, gender, ethnicity, education and wake time—factors known to be associated with diurnal cortisol rhythms (Adam & Kumari, 2009), as well as other positive and negative aspects of the marital relationship (emotional support provision and conflict), agreeableness1, and depressive symptoms. To assess whether responsiveness predicted future cortisol for all participants or just for those who remained with the same partner, we tested moderation by relationship status (same or different partner) at Wave 2. Finally, we tested whether changes in positive and negative affect over the 10-year period mediated the associations between partner responsiveness at baseline and diurnal cortisol at follow-up.

Method

The data for this study were drawn from the Midlife in the United States Project (MIDUS), a two-wave panel survey of adults between the ages of 25 and 74. This study included salivary cortisol collection for a sub-sample of participants as part of the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE). Phone interviews and self-administered questionnaires were collected in 1995-1996 (Wave 1) and again in 2004-2006 (Wave 2). A subset of participants from Wave 2 (n = 2,022) was assessed in the second wave of the NSDE (2004-2009), which is the source of cortisol data for the present analysis. Respondents participated in Wave 2 of NSDE after completing the Wave 2 MIDUS questionnaires.

Sample

In the current study, inclusion criteria were based on those individuals who provided partner responsiveness questionnaire data at Waves 1 and 2 and cortisol data at Wave 2. The sample consisted of 1,078 adults (51.9% female, 95.1% White/Caucasian). All participants in the sample were married or cohabitating at Wave 1. Of those, 970 had remained with their partner, while 43 were confirmed to be separated from their partner (due to divorce, separation, or death of the partner) or with a new spouse or new cohabitating partner (following divorce, separation or death of the initial partner); for 65 participants it was unknown whether they were still with their same partner or separated.

Measures

Covariates

Demographic covariates included age, gender (male = 1, female = 2), education (0 = high school or less, 1 = some college or more), and race/ethnicity (0 = white, 1 = nonwhite). We also controlled for average wake time across the days of salivary cortisol sampling. These are standard covariates in diurnal cortisol studies (Adam & Kumari, 2009).

Perceived Partner Responsiveness

Perceived partner responsiveness was assessed at Wave 1 and Wave 2 using three items from the MIDUS self-administered questionnaire. These items, used to assess partner responsiveness in a prior study of the links between responsiveness and mortality from the MIDUS project (Selcuk & Ong, 2013), ask participants to indicate how much their spouse or cohabitating partner cares about them, understands the way they feel about things, and appreciates them. These items match the three core components of responsiveness (i.e., understanding, validating, and caring) identified in the literature (Reis, 2012). Participants responded to the items on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all);average α = .83 across Waves 1 and 2. Responses were reverse-scored so that higher scores reflected greater partner responsiveness.

Marital Risk

A measure of marital risk (α = .72; Rossi, 2001) at Wave 1 was included to test whether partner responsiveness prospectively predicted diurnal cortisol patterns, above and beyond the effects of negative aspects of the marital relationship. The scale is comprised of five items assessing how often participants thought their relationship was in trouble over the past year (1 = never, 5 = all the time), chances that the participant and his/her partner would eventually separate (1 = very likely, 4= not at all likely; reverse-scored), and how much the participant and his/her partner disagreed about money, household tasks, and leisure time activities (1 = a lot; 4 = not at all; reverse-scored).

Perceived Emotional Support Provision

A measure of perceived emotional support provision (Rossi, 2001) at Wave 1 was included as a potential confound of the effects of perceived partner responsiveness on diurnal cortisol. Participants were asked, “On average, about how many hours per month do you spend giving informal emotional support (such as comforting, listening to problems, or giving advice) to your spouse or partner?” On average, participants reported providing 29.51 hours of support per month (SD = 55.80). Because of the free-response nature of this question, there were a handful of implausibly large values (e.g., 720 hours per month or 24 hours per day). Accordingly, outliers on this variable were winsorized to +/- 2.5 SD from the mean (Wilcox, 1998).

Trait Agreeableness

Agreeableness at Wave 1 was included as a covariate to rule out any effects of responsiveness on cortisol due to personality characteristics (e.g., people reporting high levels of partner responsiveness simply because they are highly agreeable). Using a scale constructed to assess agreeableness in the MIDUS study (Rossi, 2001), participants reported the extent to which each of 5 trait adjectives (helpful, warm, caring, softhearted, sympathetic) described them on a 4-point scale (1 = a lot, 4 = not at all); reverse-scored; α = .79.

Depressive Symptoms

A measure of depressive symptoms at Wave 1 (Kenney, Holahan, North, & Holahan, 2006) was included to test whether initial depressive symptom levels might explain the prospective association between partner responsiveness and diurnal cortisol patterns. Depressive symptoms were indexed as the total number of “yes” responses to 7 symptoms experienced for two weeks or longer during the previous 12 months when the participant “felt sad, blue, or depressed” (depressive affect subscale), and responses to 6 symptoms experienced for two weeks or longer during the previous 12 months when the participant “had the most complete loss of interest in things” (anhedonia subscale). Examples of symptoms assessed in both subscales included “lose your appetite,” “have more trouble falling asleep than usual,” and “think a lot about death.”

Positive and Negative Affect

Positive and negative affect (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) were assessed at Waves 1 and 2. Using a 5-point scale (1 = all of the time, 5 = none of the time; reverse-scored), participants were given the prompt: “During the past 30 days, how much of the time did you feel …” for 6 positive affect adjectives (e.g., cheerful, in good spirits; M = 3.49, SD = 0.66, α = .89) and 6 negative affect adjectives (e.g., nervous, restless or fidgety; M = 1.45, SD = 0.52, α = .84) at Wave 1. Slightly longer scales were used at Wave 2 with the same items from Wave 1 plus an additional 4 positive affect adjectives (enthusiastic, attentive, proud, active) and 5 negative affect items (afraid, jittery, irritable, ashamed, upset) added at Wave 2 (positive affect M = 3.58, SD = 0.66, α = .93; negative affect M = 1.48, SD = 0.47, α = .89).

Salivary cortisol

Salivary cortisol was assessed at Wave 2 using Salivettes (Sarstedt, Rommelsdorft, Germany). Saliva collection occurred 20 months after the Wave 2 phone assessment, on average (range = 3-53 months). On days 2-5 of the 8-day NSDE study period, participants self-collected saliva samples at four time points each day: immediately upon waking, thirty minutes later to assess cortisol awakening response (CAR), before lunch, and then at bedtime. Cortisol concentrations were quantified with a commercially available luminescence immunoassay (IBL, Hamburg, Germany) with intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients < 5% (Polk, et al., 2005). Saliva collection compliance was assessed using both nightly telephone interviews and paper-pencil logs included in the collection kit. Cortisol values were winsorized to +/- 2.5 standard deviations from the mean to account for outliers in the cortisol distribution (Adam & Kumari, 2009).

Data Analysis

Because of the strong diurnal rhythm of cortisol, Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) was used for data analyses. HLM allows for simultaneous estimation of multiple cortisol parameters (e.g., cortisol at wakeup, CAR and slope) and prediction of individual differences in diurnal cortisol parameters. Following prior diurnal cortisol research (Adam & Kumari, 2009), Time Since Waking, Time Since Waking2, and CAR (dummy coded 1 for the 2nd cortisol sample of the day and 0 for all other samples) were modeled at Level-1 to provide estimates of each participant’s diurnal cortisol rhythm; the coefficient for the CAR variable (π1) reflects a latent estimate of the size of each person’s CAR (additional explanation of this standard approach may be found in Adam, 2006). Second, Level-2 (person-level) effects of partner responsiveness at Wave 1 and Wave 2 were entered as predictors. Third, we controlled for potential confounds, including age, gender, ethnicity, education, and wake time at Level-2. We also included four Wave 1 psychological factors—marital risk, agreeableness, emotional support provision, and depressive symptoms—as potential confounds of the links between Wave 1 partner responsiveness and Wave 2 cortisol. Next, we tested whether the associations between Wave 1 partner responsiveness and cortisol were moderated by whether or not participants were in the same relationship at Waves 1 and 2. Finally, we tested whether changes in positive and negative affect over the 10-year period mediated the associations between Wave 1 responsiveness and Wave 2 cortisol parameters. In line with prior recommendations (Adam & Kumari, 2009), cortisol intercept, slope (effect of Time) and CAR were all allowed to vary randomly at Level-2 (e.g., treated as random effects), while Time Since Waking2 was treated as a fixed effect with no Level-2 predictors. Person-level variables were all grand-mean centered, with the exception of gender, ethnicity and education. In order to compare the magnitude of effects on cortisol across predictors, all variables were z-scored prior to analyses. Because the variables Time Since Waking and Time Since Waking2 have meaningful true zeros, we divided those two variables by their standard deviations but did not subtract their means (i.e., we did not center those two variables). This was done so that the cortisol intercept represented the standardized effect of predictors at wakeup; otherwise, the cortisol intercept in HLM analyses would reflect the effect of predictors on cortisol in the middle of the day. All HLM analyses used robust standard errors.

In addition to investigating parameters of diurnal cortisol rhythm (waking level, CAR and slope), we also investigated the associations between partner responsiveness and total cortisol output (area-under-the-curve with respect to ground, AUCg) across the four days of saliva sampling. We used standard the standard formula for computing AUCg described in Pruessner et al. (Pruessner, Kirschbaum, Meinlschmid, & Hellhammer,2003). We then used linear regression to regress AUC on perceived partner responsiveness, along with the previously described covariates. Significance tests in all analyses were 2-tailed.

Results

Intercorrelations among study variables may be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations among predictor variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wave 1 Partner Responsiveness | ------ | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Wave 2 Partner Responsiveness | .52** | ------ | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Age | .09** | .15** | ------ | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Female | -.15** | -.17** | -.12** | ------ | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Ethnicity | -.06 | -.10** | -.00 | -.03 | ------ | |||||||||||||

| 6. Education | .02 | -.03 | -.06* | -.05 | -.00 | ------ | ||||||||||||

| 7. Average Waketime | -.01 | -.02 | .03 | .10** | .00 | .06 | ------ | |||||||||||

| 8. Trait Agreeableness | .11** | .10** | .05 | .25** | -.06 | -.01 | .07* | ------ | ||||||||||

| 9. Wave 1 Emotional Support Provision | .10** | .04 | -.04 | .08** | .06 | -.07* | -.00 | .08* | ------ | |||||||||

| 10. Wave 2 Emotional Support Provision | .04 | .09** | .07* | .08** | .02 | -.05 | -.02 | .08** | .39** | ------ | ||||||||

| 11. Wave 1 Depressive Symptoms | -.09** | -.07* | -.13** | .11** | .03 | -.06 | .11** | .01 | .03 | .02 | ------ | |||||||

| 12. Wave 2 Depressive Symptoms | -.11** | -.11** | -.08* | .10** | .01 | -.10** | .10** | .05 | .05 | .06 | .29** | ------ | ||||||

| 13. Wave 1 Marital Risk | -.61** | -.37** | -.24** | .06* | .04 | .01 | .02 | -.13** | -.02 | -.02 | .15** | .11** | ------ | |||||

| 14. Wave 2 Marital Risk | -.33** | -.65** | -.23** | .06* | .12** | -.02 | -.02 | -.05 | .00 | -.05 | .09** | .15** | .47** | ------ | ||||

| 15. Wave 1 Positive Affect | .29** | .20** | .12** | -.04 | .00 | .02 | -.05 | .22** | .04 | .01 | -.31** | -.23** | -.33** | -.23** | ------ | |||

| 16. Wave 2 Positive Affect | .22** | .28** | .19** | -.05 | .00 | .04 | -.06 | .20** | -.00 | -.00 | -.19** | -.33** | -.21** | -.29** | .51** | ------ | ||

| 17. Wave 1 Negative Affect | -.25** | -.21** | -.19** | .10** | .01 | -.10** | .04 | -.08** | .06* | .04 | .38** | .32** | .30** | .22** | -.60** | -.38** | ------ | |

| 18. Wave 2 Negative Affect | -.20** | -.25** | -.18** | .08* | .03 | -.07* | .03 | -.04 | .02 | .03 | .22** | .43** | .23** | .30** | -.38** | -.61** | .54** | ------ |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05, two-tailed.

As shown in Model 1 of Table 2, participants’ cortisol values showed the expected diurnal pattern across the day, with high values at wakeup (β00 = 0.219; 95% CI: 0.180, 0.258), an increase in levels in the first 30 minutes after waking (CAR; β10 = 0.518; 95% CI: 0.485, 0.551), and a decline in cortisol levels across the day (β20 = -0.675; 95% CI: -0.720, -0.630).

Table 2.

Multilevel Growth-Curve Models of Diurnal Cortisol Parameters

| Fixed effect (independent variable) | Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | P | Estimate (SE) | P | Estimate (SE) | P | |

| Wakeup cortisol, π0 | ||||||

| Average Wakeup Cortisol (Intercept), β00 | 0.219 (0.020) | <.001 | 0.219 (0.020) | <.001 | 0.389 (0.068) | <.001 |

| Wave 1 Partner Responsiveness, β01 | 0.041 (0.017) | .016 | --- | --- | 0.043 (0.020) | .036 |

| Wave 2 Partner Responsiveness, β02 | --- | --- | 0.011 (0.017) | .54 | -0.033 (0.017) | .048 |

| Age, β03 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.074 (0.023) | .002 |

| Female, β04 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.126 (0.036) | <.001 |

| Ethnicity, β05 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.033 (0.103) | .75 |

| Education, β06 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.038 (0.038) | .31 |

| Average Waketime, β07 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.009 (0.019) | .63 |

| Wave 1 Trait Agreeableness, β08 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.011 (0.018) | .54 |

| Wave 1 Emotional Support Provision β09 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.028 (0.017) | .12 |

| Wave 1 Depressive symptoms, β010 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.032 (0.014) | .024 |

| Wave 1 Marital Risk, β011 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.012 (0.022) | .58 |

| Cortisol Awakening Response, π1 | ||||||

| Average CAR, β10 | 0.518 (0.017) | <.001 | 0.519 (0.017) | <.001 | 0.374 (0.069) | <.001 |

| Wave 1 Partner Responsiveness, β11 | -0.019 (0.016) | .24 | --- | --- | -0.025 (0.024) | .29 |

| Wave 2 Partner Responsiveness, β12 | --- | --- | 0.010 (0.017) | .53 | 0.026 (0.019) | .19 |

| Age, β13 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.084 (0.020) | <.001 |

| Female, β14 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.090 (0.038) | .017 |

| Ethnicity, β15 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.045 (0.081) | .58 |

| Education, β16 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.010 (0.039) | .80 |

| Average Waketime, β17 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.003 (0.017) | .85 |

| Wave 1 Trait Agreeableness, β18 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.001 (0.019) | .95 |

| Wave 1 Emotional Support Provision β19 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.016 (0.021) | .43 |

| Wave 1 Depressive symptoms, β110 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.017 (0.019) | .37 |

| Wave 1 Marital Risk, β111 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.016 (0.024) | .48 |

| Time Since Waking, π2 | ||||||

| Average Linear Slope, β20 | -0.675 (0.023) | <.001 | -0.676 (0.023) | <.001 | -0.730 (0.034) | <.001 |

| Wave 1 Partner Responsiveness, β21 | -0.015 (0.006) | .012 | --- | --- | -0.017 (0.008) | .041 |

| Wave 2 Partner Responsiveness, β22 | --- | --- | -0.001 (0.006) | .87 | 0.013 (0.007) | .053 |

| Age, β23 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.008 (0.007) | .29 |

| Female, β24 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.040 (0.013) | .003 |

| Ethnicity, β25 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.030 (0.028) | .27 |

| Education, β26 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.021 (0.013) | .12 |

| Average Waketime, β27 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.001 (0.007) | .88 |

| Wave 1 Trait Agreeableness, β28 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.001 (0.007) | .86 |

| Wave 1 Emotional Support Provision β29 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.011 (0.006) | .049 |

| Wave 1 Depressive symptoms, β210 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.009 (0.006) | .13 |

| Wave 1 Marital Risk, β211 | --- | --- | --- | --- | -0.002 (0.008) | .77 |

| Time Since Waking2, π3 | ||||||

| Average Curvature, β30 | 0.382 (0.020) | <.001 | 0.383 (0.020) | <.001 | 0.389 (0.020) | <.001 |

Note. Intercepts indicate average cortisol values at wakeup (in SD units); average slopes of time since waking indicate change in cortisol per 1 SD change in time; average slopes of time since waking2 indicate change in cortisol per 1 SD change in time2. CAR = Cortisol Awakening Response.

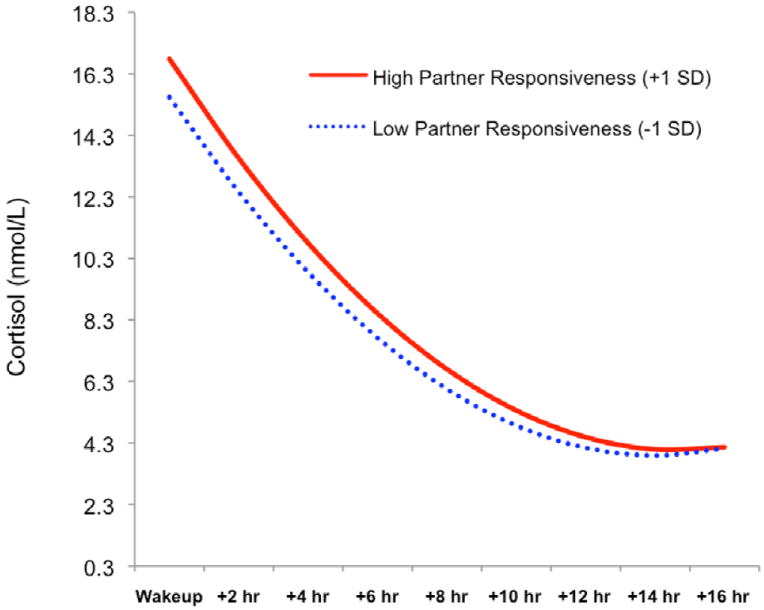

Wave 1 responsiveness was associated with higher cortisol levels at wakeup (β01 = 0.041; 95% CI: 0.008, 0.074) across the four days of saliva sampling approximately 10 years later (Model 1, Table 2). Further, Wave 1 responsiveness was associated with a steeper cortisol slope (β21 = -.015; 95% CI: -0.027, -0.003) at the 10-year follow-up. The associations between Wave 1 partner responsiveness and Wave 2 diurnal cortisol are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Associations between Wave 1 perceived partner responsiveness and diurnal cortisol at the 10-year follow-up (Wave 2). High values for partner responsiveness are plotted at +1 standard deviation and low values are plotted at -1 standard deviation from the mean (Aiken & West, 1991).

Wave 1 responsiveness explained 2.27% of the variance in cortisol slope (pseudo R = .15) and 0.5% of the variance (pseudo R = .07) in wakeup cortisol. These effects are similar to those reported in a recent meta-analysis of the associations between marital relationships and physical health (average effect sizes of r = .07 to .21 across different types of health outcomes; Robles, et al., 2014)2. Wave 2 responsiveness was unrelated to either wakeup cortisol levels or cortisol slope (Model 2, Table 2). Neither Wave 1 nor Wave 2 responsiveness was related to CAR.

We next examined whether the prospective associations between Wave 1 partner responsiveness and Wave 2 diurnal cortisol profiles remained significant when controlling for demographic characteristics, agreeableness, emotional support provision, and depressive symptoms and marital risk at Wave 1. As displayed in Model 3 of Table 2, Wave 1 responsiveness remained a significant predictor of both cortisol intercept (β01 = 0.043; 95% CI: 0.004, 0.082) and cortisol slope (β21 = -0.017; 95% CI: -0.033, -0.001), whereas Wave 2 responsiveness significantly predicted lower wakeup cortisol levels in this model (β02 = -0.033; 95% CI: -0.066, -0.0002), possibly driven by suppression effects. In addition, Wave 1 emotional support provision significantly predicted a steeper cortisol slope (β29 = -0.011; 95% CI: -0.023, -0.00003). Thus, both perceived partner responsiveness and emotional support provision (which correlated with each other r = .10; see Table 1) uniquely predicted steeper cortisol slopes at the 10-year follow-up3.

We then conducted area-under-the-curve analyses, regressing AUC on perceived partner responsiveness. Initial simple regression showed that Wave 1 partner responsiveness was not significantly related to AUC (p = .31), nor was partner responsiveness at Wave 2 associated with AUC (p = .40). When entering both Wave 1 and Wave 2 responsiveness as predictors of AUC, neither were significant predictors of AUC (p’s > .50). Further, neither were significant predictors of AUC (p’s > .60) when entered together with the covariates; the only covariates to significantly predict AUC were age (β = .15, p < .001) and average wake time (β = -.08, p = .007). Thus, perceived partner responsiveness was prospectively associated with wakeup cortisol and cortisol slope, which are markers of poor physical health, but unrelated to total cortisol output.

Possible Moderation by Relationship Status at Wave 2

We next explored whether the effect of Wave 1 partner responsiveness on Wave 2 diurnal cortisol parameters (wakeup levels and slope) was moderated by relationship status at Wave 2. In this analysis, Wave 1 responsiveness was grand-mean centered and a new variable was created to indicate those no longer with the same spouse/cohabitating partner (n = 43, effect coded -1) and those who remained continuously with their same partner between Wave 1 and Wave 2 (n = 970, effect coded 1). Wave 1 responsiveness, Wave 2 responsiveness, relationship status, and the Wave 1 responsiveness X relationship status interaction term then were entered together at Level 2 to predict cortisol. We found no evidence that the effect of Wave 1 responsiveness on cortisol parameters was moderated by relationship status (p’s of all interaction terms > .30), nor was whether or not one was separated or still with their same partner associated with cortisol parameters (all p’s > .70). Only Wave 1 responsiveness was associated with cortisol, predicting both cortisol at wakeup (β01 = 0.058, SE = 0.021, p = .006; 95% CI: 0.016, 0.100) and cortisol slope (β21 = -0.025, SE = 0.007, p = .001; 95% CI: -0.039, -0.011).

Mediation Analyses

Next, we tested whether the association between Wave 1 partner responsiveness and Wave 2 diurnal cortisol profiles could be explained by changes in affect over the 10-year period. Confidence intervals (95%) for indirect effects were estimated using an online calculator (Selig & Preacher, 2008, June) based on the Monte Carlo method for assessing 2-2-1 multilevel model mediation with 20,000 repetitions.

Positive Affect

We first tested positive affect as a mediator. Using simple regression, we determined that Wave 1 responsiveness significantly predicted positive affect at Wave 2 (b = .220, SE = 0.030, p < .001; 95% CI: 0.161, 0.279), and this effect remained significant (b = 0.083, SE = 0.028, p = .003; 95% CI: 0.028, 0.138) after controlling for Wave 1 positive affect. Wave 1 responsiveness and Wave 2 positive affect then were entered together as predictors of diurnal parameters in HLM. In this analysis, the association between responsiveness and wakeup cortisol remained significant (β01 = 0.037, SE = 0.017, p = .031; 95% CI: 0.003, 0.070), but responsiveness was no longer a significant predictor of cortisol slope (β21 = -.011, SE = 0.006, p = .079; 95% CI: -0.023, 0.001). Positive affect marginally predicted higher CAR (β12 = 0.033, SE = 0.017, p = .053; 95% CI: -0.0004, 0.067) but did not significantly predict wakeup cortisol, and only marginally predicted cortisol slope (β22 = -0.011, SE = 0.006, p = .072; 95% CI: -0.023, 0.001). Further, when controlling Wave 1 positive affect, the effect of Wave 2 positive affect on cortisol slope was not significant. These results suggest that neither Wave 2 positive affect nor changes in positive affect from Wave 1 to Wave 2 mediated the affect of Wave 1 responsiveness on Wave 2 cortisol slope.

Negative Affect

A similar approach for testing mediation was taken with negative affect. Higher partner responsiveness at Wave 1 predicted lower negative affect at Wave 2 (b = -0.196, SE = 0.030, p < .001; 95% CI: -0.255, -0.137), and this association remained significant (b = -0.066, SE = 0.027, p = .013; 95% CI: -0.119, -0.013) after controlling for Wave 1 negative affect. When Wave 1 responsiveness and Wave 2 negative affect were entered as predictors of Wave 2 cortisol, the effect of responsiveness on wakeup cortisol was significant (β01 = .039, SE = 0.017, p = .023; 95% CI: 0.005, 0.072), whereas the effect of negative affect was not (p = .63). However, higher levels of negative affect predicted a flatter cortisol slope (β22 = 0.018, SE = .006, p = .004; 95% CI: 0.006, 0.030) and a less steep CAR (β12 = -0.035, SE = 0.016, p = .035; 95% CI: -0.067, -0.002). In addition, the effect of responsiveness on cortisol slope was no longer significant (β21 = -0.009, SE = 0.006, p = 0.105; 95% CI: -0.022, 0.002). Further, the effect of Wave 2 negative affect on cortisol slope remained significant (β22 = 0.018, SE = 0.007, p = .007; 95% CI: 0.005, 0.031) when controlling for Wave 1 negative affect, indicating that a decrease in negative affect between Wave 1 and Wave 2 was associated with a steeper cortisol slope. Monte Carlo analysis indicated a significant indirect effect of partner responsiveness on cortisol slope through changes in negative affect (95% CI: -0.003, -0.0001), suggesting that the association between Wave 1 partner responsiveness and Wave 2 cortisol slope were driven by decreases in negative affect between Wave 1 and Wave 24. Because of the wide range in time lag between the Wave 2 negative affect measure and cortisol assessment (3 months to 53 months), we checked to see whether the negative affect mediation results remained significant when controlling for time lag and whether time lag moderated the association between negative affect and cortisol slope. The association between negative affect and slope remained significant in that analysis (p = .006) and the interaction between time lag and negative affect on cortisol slope was not significant (p = .09).

Discussion

We found that perceived partner responsiveness predicted diurnal cortisol profiles at a 10-year follow-up in a large sample of married and cohabitating adults in the U.S. Specifically, responsiveness was prospectively associated with steeper cortisol slopes and higher wakeup cortisol levels (which are strongly negatively correlated with cortisol slope; Adam & Kumari, 2009) but was unrelated to total cortisol output (AUC). Importantly, the associations between responsiveness and diurnal cortisol parameters remained significant after controlling for a number of possible confounds. Further, our findings suggest that the association between partner responsiveness and diurnal cortisol slope was at least partly driven by decreases in negative affect from Wave 1 to Wave 2.

This is the first study to our knowledge to show long-term longitudinal associations between the quality of one’s marital relationship and diurnal cortisol profiles. Prior work has focused on early life social experiences and how they impact future HPA axis function (for a review, see Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007). However, it has been an open question whether the HPA axis can be fundamentally altered by social relationships in adulthood in the same way that it can be altered by social relationships early in life. Our findings demonstrate that positive aspects of marriage—not only partner responsiveness but also emotional support provision—may help shape the HPA axis in beneficial ways, potentially leading to long-term changes in cortisol production.

A critical question addressed by our findings is whether the associations between partner responsiveness and future HPA axis function are stronger for those still with the same partner vs. those in a new relationship at the 10-year follow-up. We found no evidence that being in a new relationship attenuated the association between partner responsiveness and diurnal cortisol. In other words, the links between partner responsiveness and diurnal cortisol patterns 10 years later were just as strong for those who were separated and/or in new relationships as for those who remained with their partner over that entire 10 year time period. This is key preliminary evidence for lasting effects of partner responsiveness on the HPA axis, because it suggests that HPA activity remains affected by earlier social experiences, even in the presence of a new partner.

The fact that neither Wave 2 partner responsiveness nor Wave 2 emotional support provision were concurrently associated with cortisol slope suggests that possible alterations in the HPA axis stemming from positive relationship experiences occur over an extended period of time. It has been argued elsewhere (Robles, et al., 2014; Slatcher, 2010) that in order to better understand the links between marital quality and health, positive and negative aspects of marriage that feed into one’s perception of marital quality must be considered separately. This study is the first that we know of to do so with regard to the links between marital quality and diurnal cortisol, showing that positive aspects of marriage but not negative aspects are prospectively associated with HPA function in everyday life.

How big are these effects, and are they practically meaningful? The size of associations between partner responsiveness and cortisol parameters are small but comparable to those reported in a recent meta-analysis of the links between marital quality and physical health (average effect sizes of r = .07 to .21 across different types of health outcomes; Robles, et al., 2014). As noted in that meta-analysis, effect sizes of other well known health-related phenomena also are small, including consumption of fruit and vegetables and coronary heart disease (Relative Risk = .93; He, Nowson, Lucas, & MacGregor, 2007), exercise interventions for preventing declines in health-related quality of life (r = .05; Gillison, Skevington, Sato, Standage, & Evangelidou, 2009), and increased television viewing and risk for cardiovascular disease (Relative Risk = 1.15; Grøntved & Hu, 2011). Despite the fact that those are small effects, increasing fruit and vegetable intake and reducing sedentary activity are considered important targets for improving public health (U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Thus, although the effects of perceived partner responsiveness on diurnal cortisol are small, they are potentially quite meaningful when put in context along side other well-known health behaviors.

Identifying biological mechanisms underlying the links between marriage and health has been elusive. Of the various cortisol parameters assessed in daily life, cortisol slope in particular is emerging as a key to understanding the long-term impact of marital relationships on longevity because of the links between marital functioning and diurnal cortisol production (Saxbe, et al., 2008) and the links between flatter cortisol slopes and poorer health (Hackett, et al., 2014; Hajat, et al., 2013; Kumari, et al., 2011). We propose that diurnal cortisol should be considered as a potential mediator of the links between marital quality and longevity. Mortality data from future waves of the MIDUS study will allow researchers to directly test whether diurnal cortisol parameters are associated with longevity, and whether perceived partner responsiveness is indirectly associated with longevity via alterations in diurnal cortisol profiles. Further, additional waves of cortisol data will make it possible to test whether partner responsiveness is associated with changes in diurnal cortisol profiles over time.

Perhaps the most noteworthy finding from this study is the mediation of responsiveness on cortisol slope by decreases in negative affect over the 10-year period. This is the first study to our knowledge to show that declines in negative affect over time may at least partially explain the longitudinal effects of romantic relationship processes on health-related outcomes. This finding supports theoretical accounts of the links between marital quality and health (Robles, et al., 2014; Slatcher, 2010), offering empirical evidence of affective processes mediating the prospective associations between marital quality and HPA function.

Ultimately, only with replication of these findings and additional waves of data will we be able to definitively identify and articulate the mechanisms through which partner responsiveness is associated with diurnal cortisol profiles and long-term physical health. Despite the need for more data, the findings from this study offer a potentially important advance in our understanding of the long-term links between adult social relationships, psychological processes, and health-related biology.

Acknowledgments

The MIDUS I study (Midlife in the U.S.) was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. The MIDUS II research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166) to conduct a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS I investigation.

Footnotes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting that we include agreeableness and perceptions of emotional support provision as covariates in our analyses. These covariates were included in an attempt to rule out general warmth and relationship positivity that may potentially underlie the effects of perceived partner responsiveness on diurnal cortisol patterns.

Although there is no direct measure of the variance accounted for in HLM, once variables have been entered into an HLM model, one can estimate a “pseudo R2” statistic (Kreft & De Leeuw, 1998) using the formula (σ2unconditional-σ2conditional)/σ2unconditional. This formula provides an estimate of the variance explained for any random parameter (e.g., wakeup cortisol, cortisol slope) in an HLM model when adding a predictor variable (e.g., Wave 1 partner responsiveness) to an unconditional growth curve model (empty model, with no predictors at Level-2).

Additional analyses using available Wave 2 MIDUS data showed that the associations between Wave 1 responsiveness and Wave 2 wakeup cortisol (β02 = .042, SE = 0.015, p = .005; 95% CI: 0.012, 0.071) and between responsiveness and cortisol slope (β22 = -0.016, SE = 0.006, p = .013; 95% CI: -0.028, -0.003) also remained significant when using Wave 2 rather than Wave 1 depressive symptoms, marital risk, and emotional support provision as covariates (but none of those Wave 2 covariates were significant predictors of any cortisol parameters, p’s > .11).

We also conducted a mediation analysis using negative affect residualized change scores (unstandardized residual of Wave 1 negative affect predicting Wave 2 negative affect) to predict cortisol slope, which yielded virtually identical results. In that analysis, residualized increases in negative affect over time significantly predicted a flatter cortisol slope (β22 = 0.016, SE = .007, p = .013; 95% CI: 0.003, 0.029) when controlling for Wave 1 partner responsiveness. Monte Carlo analysis indicated a significant indirect association between partner responsiveness and cortisol slope through residualized changes in negative affect (95% CI: -0.003, -0.0001).

Contributor Information

Richard B. Slatcher, Wayne State University

Emre Selcuk, Middle East Technical University.

Anthony D. Ong, Cornell University

References

- Adam EK. Transactions among adolescent trait and state emotion and diurnal and momentary cortisol activity in naturalistic settings. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:664–679. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Kumari M. Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1423–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC. A secure base: Responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Gonzaga GC, Strachman AS. Will you be there for me when things go right? Supportive responses to positive event disclosures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:904–917. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison FB, Skevington SM, Sato A, Standage M, Evangelidou S. The effects of exercise interventions on quality of life in clinical and healthy populations; a meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1700–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. Psychology and the study of the marital processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:169–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grøntved A, Hu FB. Television viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2011;305:2448–2455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett RA, Steptoe A, Kumari M. Association of diurnal patterns in salivary cortisol with type 2 diabetes in the Whitehall II study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014 doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajat A, Diez-Roux AV, Sánchez BN, Holvoet P, Lima JA, Merkin SS, et al. Examining the association between salivary cortisol levels and subclinical measures of atherosclerosis: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1036–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Nowson C, Lucas M, MacGregor G. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables is related to a reduced risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Journal of human hypertension. 2007;21:717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney BA, Holahan CJ, North RJ, Holahan CK. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking in American workers. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2006;20:179–182. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan CM, Iida M, Stephens MAP, Fekete EM, Druley JA, Greene KA. Spousal support following knee surgery: Roles of self-efficacy and perceived emotional responsiveness. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54:28–32. doi: 10.1037/a0014753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz DS, McCeney MK. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: A critical assessment of research on coronary heart disease. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:541–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft IG, De Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M, Shipley M, Stafford M, Kivimaki M. Association of diurnal patterns in salivary cortisol with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: Findings from the Whitehall II study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96 doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychological bulletin. 2005;131:803. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Ostroff J, Rini C, Fox K, Goldstein L, Grana G. The interpersonal process model of intimacy: The role of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and partner responsiveness in interactions between breast cancer patients and their partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:589–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:25–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell TE, Bonanno GA, Almeida DM. Spousal loss predicts alterations in diurnal cortisol activity through prospective changes in positive emotion. Health Psychology. 2011;30:220. doi: 10.1037/a0022262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk DE, Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Kirschbaum C. State and trait affect as predictors of salivary cortisol in healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does Positive Affect Influence Health? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:916–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT. Interdisciplinary research on close relationships: The case for integration. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing theme for the study of relationships and well-being; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:140–187. doi: 10.1037/a0031859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS. Caring and doing for others: Social responsibility in the domains of family, work, and community. University of Chicago Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saxbe DE, Repetti RL, Nishina A. Marital satisfaction, recovery from work, and diurnal cortisol among men and women. Health Psychology. 2008;27:15–25. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk E, Gunaydin G, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness predicts hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: Evidence from a 10-year longitudinal study. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jomf.12272. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk E, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness moderates the association between received emotional support and all-cause mortality. Health Psychology. 2013;32:231–235. doi: 10.1037/a0028276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, Preacher KJ. Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects. 2008 Jun; Retrieved from http://quantpsy.org/

- Slatcher RB. Marital functioning and physical health: Implications for social and personality psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010;4:455–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00273.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slatcher RB, Robles TF. Preschoolers’ everyday conflict at home and diurnal cortisol patterns. Health Psychology. 2012;31:834–838. doi: 10.1037/a0026774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox R. Trimming and winsorization. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. Vol. 6. Chichester: Wiley; 1998. pp. 4588–4590. [Google Scholar]