Abstract

Cannabinoid receptor-2 (CB2) is expressed dominantly in the immune system, especially on plasma cells. Cannabinergic ligands with CB2 selectivity emerge as a class of promising agents to treat CB2-expressing malignancies without psychotropic concerns. In this study, we found that CB2 but not CB1 was highly expressed in human multiple myeloma (MM) and primary CD138+ cells. A novel inverse agonist of CB2, phenylacetylamide but not CB1 inverse agonist SR141716, inhibited the proliferation of human MM cells (IC50: 0.62~2.5 μM) mediated by apoptosis induction, but exhibited minor cytotoxic effects on human normal mononuclear cells. CB2 gene silencing or pharmacological antagonism markedly attenuated phenylacetylamide’s anti-MM effects. Phenylacetylamide triggered the expression of C/EBP homologous protein at the early treatment stage, followed by death receptor-5 upregulation, caspase activation and β-actin/tubulin degradation. Cell cycle related protein cdc25C and mitotic regulator Aurora A kinase were inactivated by phenylacetylamide treatment, leading to an increase in the ratio inactive/active cdc2 kinase. As a result, phosphorylation of CDK substrates was decreased, and the MM cell mitotic division was largely blocked by treatment. Importantly, phenylacetylamide could overcome the chemoresistance of MM cells against dexamethasone or melphalan. Thus, targeting CB2 may represent an attractive approach to treat cancers of immune origin.

Keywords: cannabinoid receptor-2, multiple myeloma, apoptosis, cell cycle, cytoskeleton

INTRODUCTION

Emerging evidence has demonstrated promising effects of cannabinoids on inhibition of tumor cell growth by modulating different cell signaling pathways in diverse cancer cells, such as lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma cells, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and skin cancer cells [1–7]. Natural and synthetic cannabinoids act by interacting with two distinctive G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors, subtype 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2) [8,9]. CB1 is expressed abundantly in central nervous system and certain peripheral nerve terminal sites, whereas CB2 is expressed dominantly in the immune system, especially on plasma cells [10,11]. Because of the public concerns that compounds with high affinity binding to the CB1 subtype may develop the complications of depression and suicide trends [12], research and development of compounds with high CB2 selectivity have brought up much attention [13]. CB2 receptor is an attractive molecular target for developing non-psychotropic (or non CB1-mediated) chemical agents to treat various human diseases including inflammation and cancers of immune origin [1–7].

Recently, we have found that CB2 is highly expressed in multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines and primary MM cells, indicating CB2 may be a potential drug target for MM intervention [14]. MM is an incurable hematologic malignancy, characterized by the aberrant proliferation of terminally differentiated plasma cells and impairment in the apoptosis capacity of these cells [15]. CB2 receptor is predominantly expressed on B cells whereas MM is a cancer of plasma cells of B cell origin. However, to our best knowledge, the CB2 signaling pathway has not been explored as a potential therapeutic target in multiple myeloma.

Compound N,N′-((4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) methylene) bis (2-phenylacetamide) or named as phenylacetylamide (PAM), was first discovered in our lab for its CB2 binding selectivity and antagonism properties by using 3D pharmacophore database screening approach [16–20]. Structurally, PAM possesses a non-ring-type centroid moiety that is different from the structures of the reported CB2 ligands [20]. 3[H]-CP55940 radiometric binding assay and LANCE assay confirmed that PAM exhibits high CB2 selective affinity and acted as a CB2 inverse agonist [20]. In this study, we have reported our recent findings that CB2, but not CB1, is highly expressed in MM cell lines and human primary myeloma cells. Targeting CB2 with PAM inhibits myeloma cell proliferation by inducing cell apoptosis, and such inhibition activities are retained to the drug resistant MM cells. CB2 gene silencing resulted in the functional loss of PAM-mediated MM cell death. PAM treatment disrupted cell cycle progression, upregulated the death receptor-5 and induced cytoskeleton degradation in the treated MM cells. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the anti-myeloma activities of cannabinoid receptor ligands. These studies provide further insight on how CB2 ligands exert their anti–multiple myeloma effects, and the preclinical rationale for future in vivo investigations using PAM to improve MM patient outcome either alone or in mechanism-based combination regimen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

Human MM cell lines U266, H929, RPMI-8226 and its subline RPMI 8226/LR5 (resistant to melphalan), MM.1S and its subline MM.1R (resistant to dexamethasone) were cultured as described previously [21,22]. The chemoresistant cell lines were cultured in the presence of melphalan or dexamethasone, and resistance phenotype was confirmed by cell proliferation assays. Cell-permeant pan caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The well-known cannabinoid ligands used in the present study were provided by NIH-NIDA-NDSP program: CB2 inverse agonist SR144528 (CAS Number 192703-06-3, CB2 Ki: 0.6 nM), CB1 inverse agonist SR141716 (CAS Number 168273-06-1, CB1 Ki: 1.8 nM), CB1/CB2 agonists CP55940 (CAS Number 83002-04-4, CB1 Ki: 0.58 nM and CB2 Ki: 0.69 nM) and Win55212-2 (CAS Number 131543-23-2, CB1 Ki: 62.3 nM and CB2 Ki: 3.3 nM). The known CB2 inverse agonist AM630 (CAS Number 164178-33-0, CB2 Ki: 31.2 nM) and CB2 agonist Hu308 (CAS Number 256934-39-1, CB2 Ki: 20 nM) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). The radioligand [3H]-CP55940 used for receptor binding assay was obtained from Perkin–Elmer (Boston, MA). The compound PAM (N,N′-((4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) methylene) bis (2-phenylacetamide)) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Product number L248495, St. Louis, MO).

CB2 gene silencing in MM cells

To confirm the significance of the CB2 pathway in PAM-induced myeloma cell apoptosis, we introduced a shCB2 (short hairpin CB2) construct with a MISSION® shRNA lentiviral kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) into MM.1S cells to silence the expression of endogenous CB2. After puromycin selection, the MM.1S subline stably expressing shRNA against CB2 was confirmed by Western blot.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and human marrow CD138+ cells

The fresh human PBMCs were prepared and provided by the Immunologic Monitoring and Cellular Products Laboratory to explore the cytotoxicity of CB2 ligands [23]. Human primary CD138+ cells purified from bone marrow aspirates of MM patients were obtained as previously described [24]. These studies conformed to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh.

3H-thymidine incorporation assay

3H-Thymidine incorporation assays were carried out to investigate the effects of CB2 ligands on cell proliferation. U266, RPMI-8226 (3 × 104 cells/well), MM.1S cells (6 × 104 cells/well), and their resistant sublines were cultured in 96-well culture plates with or without drugs for 48 hours. DNA synthesis was measured by 3H-thymidine uptake as described previously [24].

Computer molecular modeling and docking studies

Computer molecular modeling and docking studies were carried out using Tripos molecular modeling packages Sybyl X1.3, based on the reported 3D CB2 receptor structural model [25]. Docking of CB2 ligands SR144528 and PAM as well as CB2 protein-ligand complex MD/MM studies were performed on the basis of previously published docking protocols [26], using the Surflex-dock program in Tripos molecular modeling packages Sybyl X1.3.

Assessment of apoptotic cell death and cell viability

Apoptosis was assessed morphologically by nuclear condensation and fragmentation using Hoechst 33342 nucleic acid staining as previously described [27]. Hoechst 33342 staining–positive cells with apoptotic bodies or condensed and fragmented nuclei were considered and counted as apoptotic cells. Caspase-3, -8, and -9 activities were measured as described previously [27]. Viability of cells was determined by trypan blue staining (0.4%) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), which distinguishes the membrane defective dead cells from the viable cells.

Cell cycle analyses by flow cytometry

Effect of CB2 ligand PAM on myeloma cell cycle was determined by propidium iodide staining and subjected to the analysis of BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (San Jose, CA) following our reported protocol [22].

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR was used to measure mRNA level changes of the target genes. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primer sets used to amplify specific sequences were gapdh 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′, β-actin 5′-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-3′ and 5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3′. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously [27]. Primary antibodies used were those against CB1, CB2 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), phospho-JNK, phospho-ERK, phospho-p38 MAPK, phospho-CDK substrates, phospho-Aurora-A/B/C, phospho-cdc2, cdc2, phospho-cdc25C, phospho-H2A.X, survivin, CHOP, caspase-8, Bid, Bim Bax, (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA), β-tubulin, β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), DR4 and DR5 (ProSci, Poway, CA), and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX).

Statistical Analysis

Data were measured as triplicates and presented as mean and SD. The significance of differences between experimental variables was determined using Student’s t test. The results were considered to be statistically significant at a value of P < 0.05. All statistical tests were two tailed.

RESULTS

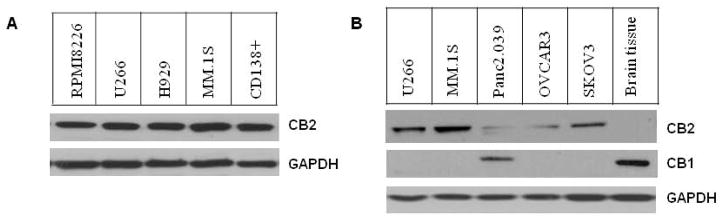

CB2 receptor is highly expressed in MM cells

We determined the CB2 expression levels in human MM cell lines ((RPMI-8226, U266, MM.1S and H929) as well as primary CD138+ cells from MM patients. As shown in Figure 1A, all the tested human MM cells produced high levels of CB2 receptor. To further assess cannabinoid receptor subtypes in human MM and non-MM cells, we compared the expression levels of CB1 and CB2 using the indicated human cell lines. As shown in Figure 1B, compared to the faint expression of CB2 in non-MM cancer cells (e.g. pancreatic cancer panc2.03 9, ovarian OVCAR3 and SKOV3), CB2 protein in MM cells (U266, MM.1S) were robustly expressed. In addition, CB1 was expressed mainly in the brain tissue as expected (Figure 1B), but not in MM cells. Interestingly, human pancreatic cancer cell panc2.03 9 also highly expressed CB1 receptor (Figure 1B). The observed distinct expression patterns of cannabinoid receptors between MM and non-MM cancer cells suggests that CB2 pathway may play a certain role in keeping cellular function integrity and tightly-regulated pathways of MM cells in response to CB2 ligand treatment.

Figure 1.

Cannabinoid receptor expression in human cancer cells. (A) CB2 expression in various human MM cell lines and primary CD138+ MM cells. Cells in logarithmic phase were harvested and lysed by RIPA buffer containing protease cocktail inhibitors. Whole-cell lysates (25 μg) were subjected to immunoblot assay and detected with CB2 antibody. (B) The protein levels of CB1 and CB2 in MM cells (U266, MM.1S) and non-MM cells (pancreatic cancer panc2.03 9, ovarian cancer OVCAR3 and SKOV3) were determined by immunoblot assay (whole-cell lysates 20 μg). To justify the expression difference of CB1 and CB2, mouse brain tissue lysate was used for the specific expression of CB1.

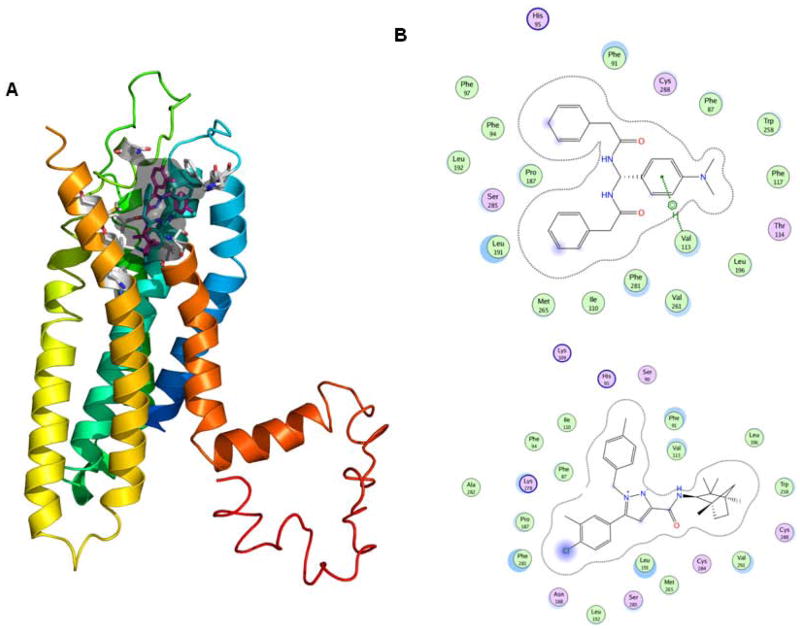

Molecular interaction of PAM and CB2 receptor

PAM was first discovered in our lab for its CB2 binding selectivity and antagonism properties by using 3D pharmacophore database screening approach [16–20]. 3[H]-CP55940 radiometric binding assay and LANCE assay confirmed that PAM exhibits high CB2 selective affinity and acted as a CB2 inverse agonist [20].

Computer modeling docking studies demonstrated that PAM may be docking to the binding pocket of the well-known CB2 inverse agonist SR144528. In our previous studies, we also performed mutation analysis and demonstrated the critical roles of Val113 and Leu192 of CB2 receptor in the binding of PAM analogs [28].

As shown in Figure 2A, PAM possesses a docking pose similar to the SR144528 surrounded by the hydrophobic residues in a range of 3.1 to 4.2 Å, including the reported Trp258, V113, Leu196, Val261 as well as newly predicted residues Phe281 and Thr114, and also possess H-bonding interactions (in a range of 2.8 to 3.5 Å) with reported polar residue Ser285 of the CB2 receptor as defined previously [28] (Figure 2B). These data suggested that PAM is an important lead compound as a cannabinoid CB2 receptor-selective ligand and behaves like an inverse agonist.

Figure 2.

PAM interacts with CB2 receptor. (A) 3D docking poses of CB2 ligands PAM and SR144528 in CB2 receptor and the small grey area view of docking pocket (Sybyl X1.3). (B) 2D view of interaction maps of the CB ligands (top: PAM and bottom: SR144528) and the surrounded binding amino acid residues that were measured from docking poses (Schrondinger).

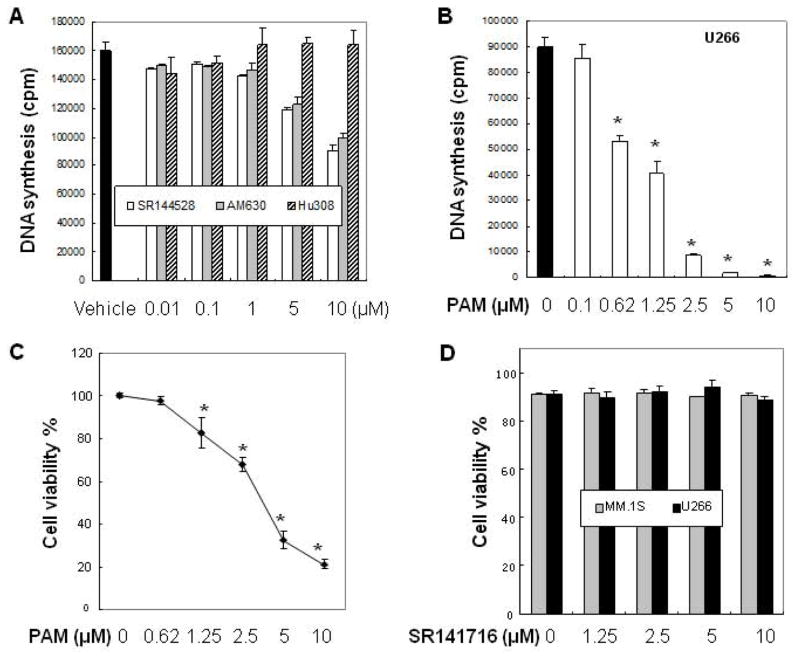

CB2 ligands inhibit the proliferation of human MM cells

To determine which type of CB2 ligands (agonist or inverse agonist) may show anti-MM activity, we investigated the effects of these compounds on myeloma cell proliferation using thymidine uptake assays. Among the CB2 ligands tested, we found CB2 selective inverse agonists (SR144528 and AM630) inhibited myeloma cell U266 proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. On the contrary, CB2 selective agonist Hu308 showed ineffective even when the concentration was increased to 10 μM (Figure 3A). Based on these results and the CB2 antagonism property of PAM [20], we explored the inhibitory effect of PAM on MM growth. As demonstrated in Figure 3B, treatment of U266 cells with the CB2 inverse agonist PAM for 48h inhibited myeloma cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (IC50: 1.25 μM). Further, trypan blue exclusion assays indicated that PAM exposure significantly decreased the viability of U266 cells (Figure 3C). Impressively, the known CB1 selective inverse agonist SR141716 (Ki = 1.8 nM) failed to show cytotoxicity on MM cells using the same concentration range (Figure 3D), consisting with the absence of CB1 in MM cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 3.

CB2 ligands inhibit the proliferation of human MM cells in a CB2-dependent manner. (A) Inhibitory effects of cannabinoid ligands on MM cell growth. Human MM cell U266 (3 ×104 cells per well in 96-well plate) was exposed to the known CB2 ligands at indicated concentrations (0–10 μM) for 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine uptake assay as described in Materials and Methods. (B–C) Inhibitory effects of PAM on MM cell growth. U266 cells were treated with PAM at indicated concentrations for 48 h. Cell proliferation and viability were determined using [3H]-thymidine uptake assay and trypan blue exclusion assay under inverted microscope, respectively. (D) CB1 inverse agonist SR141716 has no effects on MM cell growth. Human myeloma cells (MM.1S or U266) were treated with SR141716 at indicated concentrations for 48 h. The cell viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion assay. (E) Anti-proliferative effects of PAM on human chemoresistant myeloma cell lines. Human chemoresistant myeloma cell lines MM.1R (resistant to dexamethasone), RPMI-8226/LR5 (resistant to melphalan) and their respective parent cells MM.1S and RPMI-8226 were exposed to PAM for 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation. (F) Effects of PAM on normal PBMC and marrow mononuclear cells. Samples of primary PBMCs cells (left panel) or bone marrow cells (right panel) (5×104 cells per well in 96-well plate) from healthy donors were treated in culture for 40 h with the indicated compounds. The viability of cells was determined using trypan blue exclusion assay. (G) CB2 knockdown diminishes the inhibitory effect of PAM on MM cell proliferation. CB2 gene silencing in human MM.1S cells was confirmed by Western blot determined with CB2 specific antibody (left panel). MM.1S cells expressing the shRNA vector or expressing the specific shRNA against human CB2 were treated with vehicle control (white bar) and the indicated concentrations of PAM (black bar) for 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation (right panel). (H–I) U266 cells were treated with PAM in the absence or presence of CB2 agonist Win55212-2 or CP55940 for 48 h. The cell viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion assay. The data presented are the mean ± SD of at least 3 independent measurements. * P<0.05 represent significant differences as compared with the corresponding vehicle controls, or with PAM treatment only (in H and I).

PAM also showed significant growth-inhibitory effects on other human MM cells including MM.1S (Figure 3E, left panel) and RPMI8226 (Figure 3E, right panel). Since drug resistance is a prevalent problem in multiple myeloma [29], we determined whether PAM overcomes the chemoresistance of MM cells against conventionally used drugs such as dexamethasone or melphalan. The chemoresistant phenotypes of MM.1S subline MM.1R and RPMI-8226 subline 8226/LR5 have been confirmed and described previously [22]. In this study, MM.1R and 8226/LR5 exhibited similar or better responses to PAM treatment (IC50 ranging from 0.6 to 1.2 μM) than their parental cell lines (Figure 3E), suggesting that PAM may overcome the chemoresistance that resulted from the classic pathways of drug action in MM cells. Importantly, normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were resistant to the CB2 ligand treatment. The tested compounds (PAM and SR144528) had no significant affects on the viability of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells at concentrations in the IC50 range for inducing apoptosis of MM cells (Figure 3F, left panel). PAM had some minor toxicity against human bone marrow mononuclear cells at higher concentration (5 μM). This toxicity, however, was much lower than that found in MM cells (12% for marrow cells vs. 70% for MM cells) (Figure 3F, right panel vs. Figure 3C).

CB2 expression is critical for PAM-induced MM cell death

To further clarify the involvement of CB2 pathway in PAM-induced myeloma cell death, we employed genetic and pharmacological approaches to block CB2 molecular signaling and measured anti-MM effect of PAM. The stable knockdown of the CB2 receptor (>75%) by shRNA technology was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 3G, left panel). As expected, the inhibitory effects of PAM on MM cell proliferation was largely abrogated in MM.1S cells stably expressing shRNA against CB2 (Figure 3G, right panel, and Figure 3E, left panel), suggesting the direct implication of the role of cannabinoid receptor 2 in PAM-induced MM cell death.

Furthermore, to characterize the role of CB2 in PAM signal transduction in MM cells, we pretreated the cells with different combinations of CB2 agonists along with the CB2 inverse agonist PAM. As shown in Figure 3H and 3I, cannabinoid receptor agonist Win55212-2 or CP55940 could partially but significantly attenuate PAM-mediated decrease in the viability of MM cells. CP55940 showed stronger activity to reverse the effect of PAM on MM cells than Win55212-2. These functional antagonism data further demonstrated that CB2 receptor is a mediator of PAM-induced myeloma cell death.

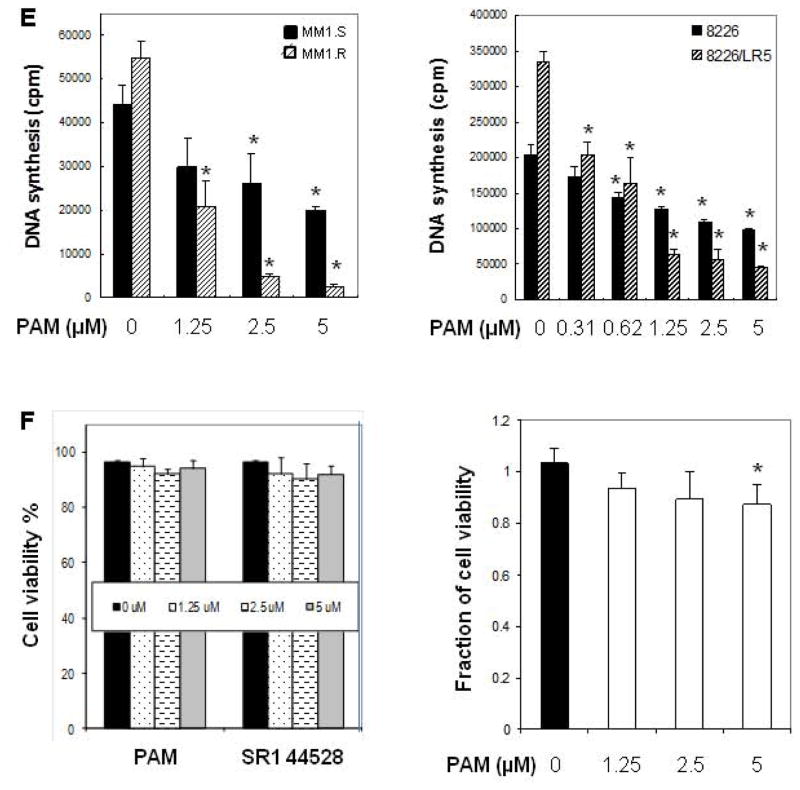

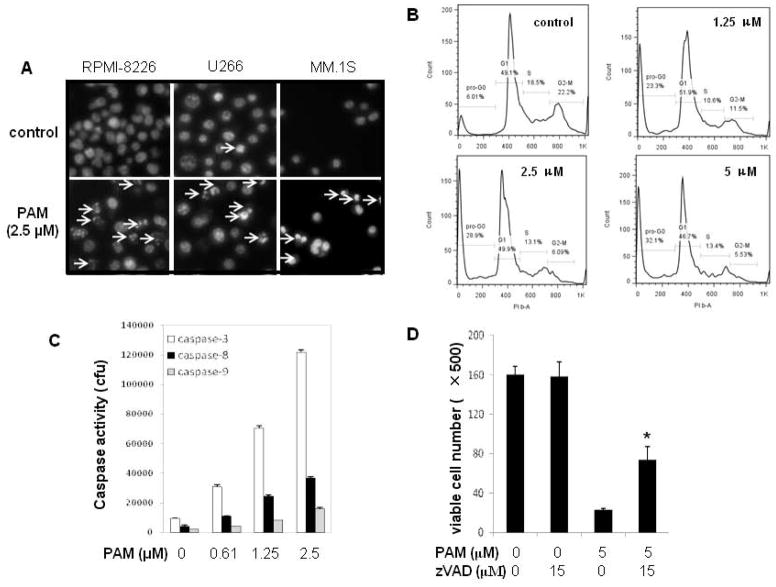

Role of apoptotic death in the anti-proliferative effects of PAM on MM cells

As shown by the increased number of Hoechst33342-positive cells with nuclear condensation and fragmentation as well as subG0/G1 population (Figure 4A–4B), the anti-myeloma effect of PAM involves the induction of cell apoptosis. The proapoptotic effect of PAM was caspase dependent since caspase-3, -8, and -9 were all activated after PAM treatment (Figures 4C). Blockade of caspase activation by zVAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor, partly prevented the cell death inducted by PAM (Figures 4D). These results indicate that PAM-induced apoptosis involves both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways.

Figure 4.

PAM treatment induces MM cell apoptosis and caspase activation. (A) MM cell lines (RPMI8226, U266 or MM.1S) were treated with PAM (2.5 μM) for 24 h. Cells were then stained with Hoechst 33342. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells with condensed or fragmented nuclei. (B) After treated with PAM (0–5 μM) for 24 h, U266 myeloma cells were fixed in cold 70% ethanol and subjected to flow cytometry assay for cell cycle using PI staining. (C) Human myeloma U266 cells were exposed to PAM (0–2.5μM) for 18 h. Cells were harvested and lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease cocktail inhibitors. Caspase-3, -8, and -9 activities in the cell lysates were measured as described in Materials and Methods. (D) U266 cells (3×104 per well in 96-well plate) were pretreated with or without the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (15 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to PAM (5 μM) for 36 h. The viable cell numbers per well were determined using trypan blue exclusion assay. Results represent mean ± SD of at least three assays performed. * P<0.05 represent significant differences as compared with PAM treatment only. (E–G) Human MM cells U266 treated under the indicated conditions were lysed with RIPA buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Lysates (30 μg) were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The phosphorylation of MAPK members and H2A.X, CHOP protein (E) and apoptosis-related molecules (F, G) were detected using the combination of primary and secondary antibodies and followed by Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham, GE Healthcare).

Next, we explored the possible signal events involved in PAM-induced MM cell apoptosis. Among the many signaling pathways that respond to cell stress, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family members are crucial for the maintenance of cells [30]. The MAPK signaling pathways that trigger a cell to undergo apoptosis in response to cannabinoids are cell type specific and are currently being defined [31]. Our data clearly showed that, after PAM treatment, ERK and JNK were activated at 1.5 h and peaked around 3 h, but p38 MAPK was less affected (Figure 4E). Interestingly, blockade of JNK with its specific inhibitor SP600125 (0–50 μM), which directly inhibits c-Jun phosphorylation, had no inhibitory effects on the proapoptotic induction of PAM in MM cells. The ERK pathway inhibitor U0126 and p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 also failed to rescue MM cells from PAM’s cytotoxic effects (Supplementary Figure), suggesting that the activation of the JNK and ERK pathways makes no direct contribution to the anti-MM activity of the CB2 ligand PAM. PAM treatment had no effect on H2A.X phosphorylation (Figure 4E), which is reported to be critical for DNA damage and apoptosis by sustained JNK activation [32]. In addition, endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced transcription factor, CHOP, was transiently upregulated by PAM (Figure 4E). After that, CHOP-targeted gene death receptor (DR) 5a [6,33], but not DR4, was consequently upregulated as well (Figure 4F).

In view of the aforementioned data, we further investigated whether DR5-linked downstream molecules were involved in this cell death process. Caspase-8 and Bid were activated after PAM treated for 3 h and beyond (Figure 4G). However, the mitochondrial pathway was weakly affected by PAM. As shown in Figure 4G, neither Bim isoforms nor Bax was phosphorylated or upregulated by PAM treatment. Anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was slightly decreased. These observations were consistent with our caspase activity assays (Figure 4C), in which caspase-8 was greatly activated than caspase-9, an initiator caspase in mitochondrial pathway. PAM treatment also decreased survivin levels, a member of the IAP family of anti-apoptotic proteins (Figure 4G), which may facilitate the activation of caspases and apoptotic process [34].

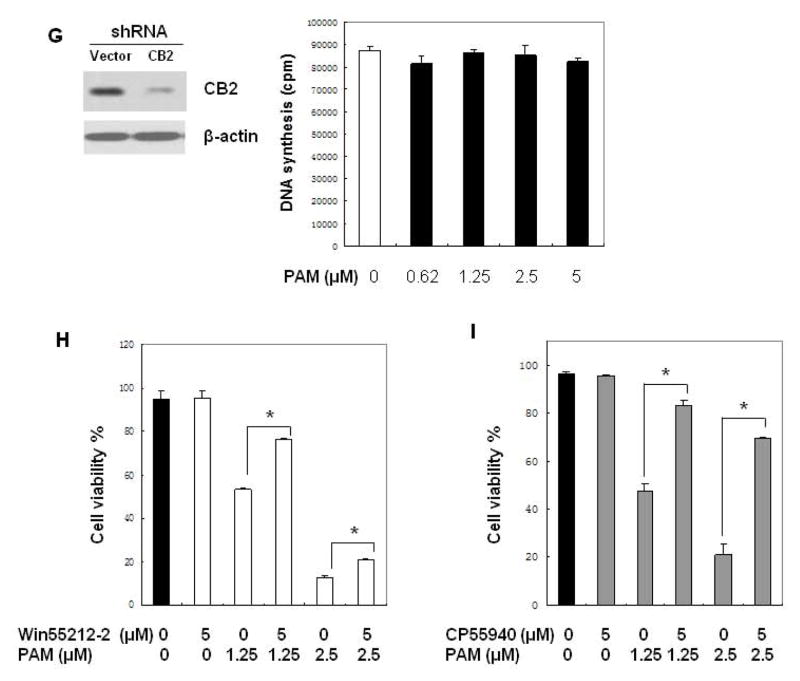

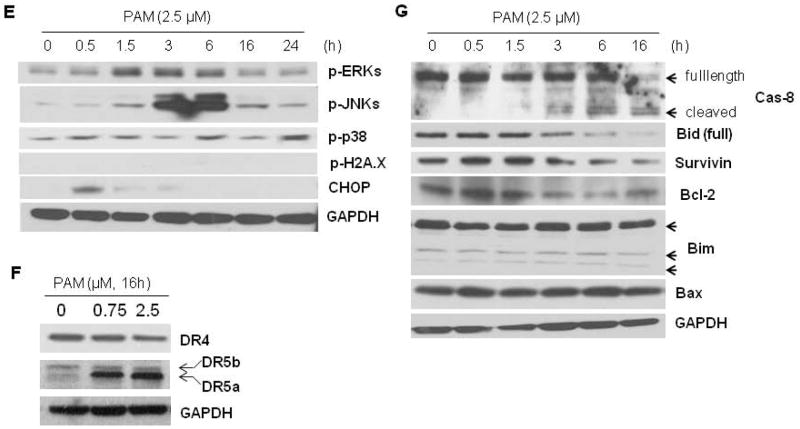

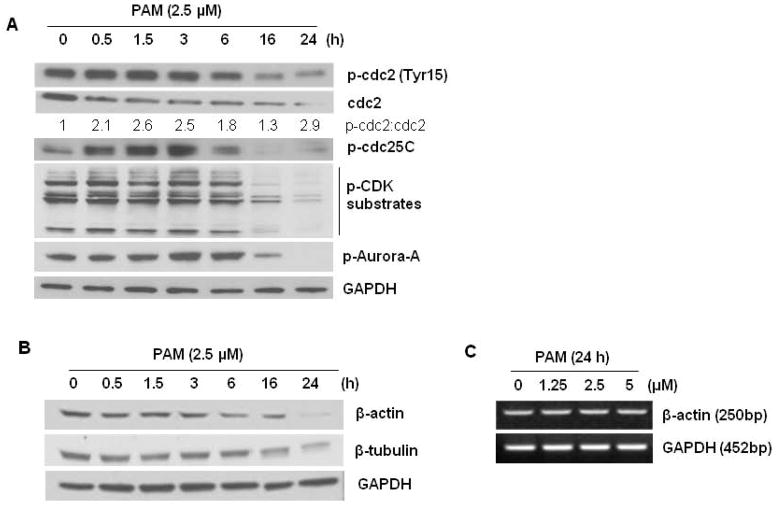

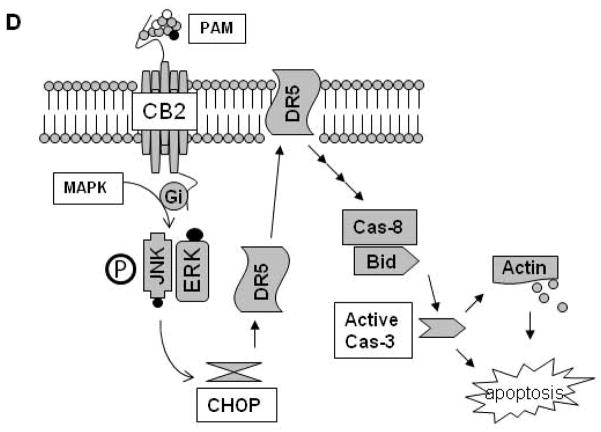

The effects of PAM on cell cycle-related proteins and cytoskeleton system

Based on our data of cell cycle analysis, we next determined whether an alteration of the MM cell cycle underlies PAM anti-proliferative effect. PAM treatment maintained the number of cells in the G0–G1 compartment but significantly decreased the number of cells in S phase and G2-M in a dose dependent manner (Figure 4B). In parallel, subG0/G1 population cells increased dramatically (Figure 4B). The number of polyploid cells (N > 4) was only slightly increased after the U266 cells were treated with PAM for 24 h. This increase was concentration dependent from 0.5 μM to 2.5 μM from an initial 9.4% to 11.9%, respectively (Supplementary Table). To analyze the underlying mechanism of action for PAM, we probed the expression of several proteins involved in the G2-M transition. As a tyrosine phosphatase, Cdc25C activates cyclin B-bound Cdc2 (Cdk1) by removing inhibitory phosphate residues and triggers entry into mitosis by controlling the transitions from G1 to S phase and G2 to M phase [35]. PAM treatment caused a transient increase in the activation of Cdc25C, which was then sharply decreased to a hardly detectable level after 16 h and beyond. Furthermore, PAM reduced the amount of Cdc2 to a much greater extent than phosphorylated Cdc2 at Tyr15 (Figure 5A), indicating that the ratio inactive/active Cdc2 was increased by PAM. As a result, PAM treatment could markedly lower the phosphorylation levels of Cdk substrates (Figure 5A), which are well known to be critical for mitotic entry and cell cycle progression. One of family members of mitotic serine/threonine kinases, Aurora A kinase (or serine/threonine-protein kinase 6) that served as the marker of a G1/G2 ratio change, was also inactivated after 16 h treatment of MM cells with PAM (Figure 5A). These results suggest that PAM exhibits its negative regulation on myeloma cell cycle through different checkpoints at different levels and subsequently induce mitotic cell death. Subsequently, we examined the effect of PAM on the cytoskeletal system. As shown in Figure 5B, protein levels of β-actin and β-tubulin were all downregulated after PAM treatment for 16 h and beyond. However, we failed to observe any degraded messenger RNA of β-actin even with higher doses of PAM for 24 h (Figure 5C), suggesting that PAM induces downregulation of these cytoskeletal proteins through posttranslational modification mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Effects of PAM treatment on cell cycle-related proteins. U266 cells treated under the indicated conditions were lysed with RIPA buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Lysates (30 μg) were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The cell cycle-related proteins (A) and cytoskeleton (B) were detected using the combination of primary and secondary antibodies and followed by Western blotting detection reagents. To highlight the ratio change of inactive/active cdc2 after PAM treatment, optical density (arbitrary units) of the phosphorylated and total cdc2 relative to their respective time-point control incubations (set at 100) was measured and then the ratio was showed below their bands. GAPDH was used as the loading control. (C) RT-PCR analysis for messenger RNA of β-actin and GAPDH transcripts. The details are described in the Materials and Methods Section. (D) Hypothetical model for involvement of activation of death receptor components in PAM-induced MM cell apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

Despite the development of novel treatment approaches and high-dose therapies, MM remains incurable. There is an urgent need, therefore, for the development of new therapeutic strategies for MM patients. Selective apoptosis induction has been widely accepted as an ideal way to eliminate cancer cells and could provide suitable targets for cancer treatment and prevention [23,36,37]. One of the most exciting and promising areas of current cannabinoid research is the ability of these compounds to control the cell survival/death decision [4,38]. In the present study, we found that the expression of CB2 receptor in MM cells was higher than that in other kinds of non-B cell cancers, which is consistent with the conclusion of dominantly expression of CB2 in plasma B cells [10,11,39]. This finding opens up a new avenue to develop a reasonable strategy to treat MM via the CB2 pathway. Our data showed that the known CB2 ligands (mainly inverse agonists) and our lead compound PAM with CB2 selectivity exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of MM cell proliferation (Figure 3). Furthermore, PAM could decrease MM viability and overcome chemoresistance via selective apoptosis induction. It is worth noting that, however, the affinity of CB2 ligands to the receptor is not directly proportional to the anti-MM potency. Though SR144528 has been reported to exhibit higher affinity to CB2 receptor than PAM [40], PAM is more potent to inhibit the proliferation of MM cells in the present study. We speculate that this may be resulted from some unspecific activities and the anti-MM effects of PAM involve multiple mechanisms.

Silencing CB2 gene expression or pretreatment of MM cells with CB2 agonists significantly counteracted the effects of PAM. On the contrary, CB1 receptor ligand SR141716 failed to induce U266 cell death with the same concentration range as that tested for CB2 compounds. These results suggest that targeting CB2 receptor represents an effective approach to induce MM apoptosis, without observable effects on normal cells. Importantly, targeting CB2 will bypass the possible severe psychotropic side effects that are usually associated with CB1 interaction [11,12].

Of interest, CB2 inverse agonist PAM has no obvious cytotoxic effects on normal human PBMCs in the IC50 concentration range for inducing apoptosis of MM cells. This apparent tumor cell selectivity may result from the distinct CB2 expression profiles of the normal and MM cells, since different activated cells may exhibit a different activation status for CB2 expression [41]. In addition, the high expression of cannabinoid receptors compared to normal cells/tissues has been reported in various different malignancies [42,43]. Normal B cells expressing lower levels of cannabinoid receptors than leukemia cells, exhibit minor or none response to cannabinoid treatment [44]. However, the exact mechanisms by which normal B cell or other cell types resistant to CB2 ligand insult need to be further clarified.

Stress-induced sustained MAPK activation plays a critical role in the subsequent cell death [23,32,45]. In our system, however, MAPK activation contributed little to the proapoptotic effects of PAM in MM cells. PAM treatment markedly but transiently activated ERK or JNK, but their specific inhibitors failed to inhibit PAM-induced cell death. Human DR5 has two isoforms, designated as DR5a (short) and DR5b (long), which result from pre-mRNA alternative splicing [46]. The TRAIL receptors, DR4 and two isoforms of DR5 exhibit the same cell death-inducing effects through the clustering of the death domains [46]. In our study, we found that PAM triggered ERK and JNK transient activation, CHOP upregulation and later on DR5a upregulation, whereas ERK/JNK phosphorylation and CHOP transactivation have been proposed to be necessary for DR5 upregulation in chemical-induced cancer cell death [6,33,47]. Thus, ERK/JNK transient phosphorylation might play indirect roles in PAM-induced MM cell death by modulating proapoptotic protein expression. This needs further explored.

Our data reveal that PAM-induced apoptosis involves both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways, and suggests that caspase-8 activation plays a more dominant role than caspase-9 as the initiator caspase in MM cell death induced by PAM. In addition, the expression levels of Bcl-2 family proteins (i.e. Bcl-2, Bax and Bim) that are crucial regulators for the intrinsic apoptotic pathway were not affected by PAM treatment. Thus, we speculate that the downstream signals of PAM treatment may involve the interaction of the GPCR with death receptor complex. PAM-induced survivin degradation may enhance death receptor-mediated apoptosis [48]. On the other hand, survivin is expressed in cells during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, followed by rapid decline of both mRNA and protein levels at the G1 phase [48]. Our cell cycle assays showed that G2/M population cells were markedly decreased after PAM treatment. Thus, PAM-induced survivin downregulation may also result from the significant reduction of cells in G2/M phase.

A number of potential molecular targets for novel anticancer drug discovery have been identified in cell cycle control mechanisms [49,50]. Cdc25C is a dual-specificity protein phosphatase that controls entry into mitosis by dephosphorylating the protein kinase cdc2 at Tyr15. In addition, interaction of cyclin B with Cdk1 will facilitate the binding of Cdk1 substrates to its active site; phosphorylation of these target substrates will lead to cell cycle progression. Elevated expression and activities of Aurora kinases (A/B/C) have been found in various malignancy cells. Of them Aurora A functions during prophase of mitosis and is required for correct function of the centrosomes, which is pivotal to the successful execution of cell division. Therefore, inhibition of cdc25 and Aurora kinases is an important therapeutic strategy for cancer anti-mitotic therapy. In this study, PAM treatment led to a sharp decrease in the phophorylation of cdc25C and thereby lost the ability to dephophorylate inactive cdc2 for the following cdc2 substrates phosphorylation. While we failed to observe any changes of Aurora B/C after PAM treatment, phosphorylation of Aurora A (at T288) in its catalytic domain was markedly reduced at 16 h and completely disappeared 24 h later (Figure 5A). Our cell cycle analysis suggests that PAM may block the transition from G2 to M phase and then shift the cell cycle to the accumulation of pro-G0G1 population by successively interrupting cdc25C/cdc2/CDK-substrates and Aurora kinase activity.

Cells undergoing apoptosis are characterized by significant morphologic changes: cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and formation of apoptotic bodies. Mechanisms that cause these changes may involve the breakdown of the cytoskeleton. Actin has been reported to be a substrate of various activated caspases; actin cleavage may activate DNase I leading to the subsequent nuclear fragmentation [51,52]. While cannabinoids may also disrupt the networks of microtubules and microfilaments and inhibit actin/tubulin expression [53], few studies link cytoskeleton breakdown with CB ligands-induced cancer apoptosis. In our system, we found PAM decreased the protein levels of β-actin and β-tubulin but failed to affect the mRNA transcript, indicating the critical role of activated caspase-induced posttranslational modification in the cytoskeletal degradation by PAM treatment.

In conclusion, we have for the first time reported that CB2 was highly expressed on MM cells and shown the anti-MM activity of CB2 inverse agonist PAM via apoptotic induction, during which death receptor pathway, cell cycle inhibition and cytoskeleton breakdown are involved in this apoptotic process (Figure 5D). Further in vivo preclinical studies of PAM as a novel anti-MM agent thus certainly seem to be warranted.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure. MAPK inhibitors fail to rescue PAM-induced MM cell death. Human U266 cells were pre-treated with the indicated inhibitors (SP: SP600125 for JNK; U0126 for ERK/MEK; SB: SB203580 for p38 kinase) at indicated doses for 30 min and followed by exposed to PAM (5μM) for another 48 hrs. The cell viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion assay under inverted microscope. Data represent the results of one experiment.

Supplementary Table. PAM treatment slightly increases the polyploidy fraction in the treated MM cells. U266 cells (1× 106) were plated on a 6-well plate in growth medium and treated 24 h after plating with different concentrations of PAM (0–2.5 μM). After treatment, the cells were washed with PBS. The cell pellet resuspended in 3 ml of ice cold ethanol (70% v/v) to fix the cells for overnight at 4°C. For the propidium iodide staining, an aliquot of cells was removed, pelleted and washed with PBS containing 1% fetal bovine serum. Finally, cells were resuspended in 1 ml staining solution [PBS containing 1% (v/v) FBS, 500 μg/ml RNAse (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μg/ml propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen)] and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, while protected from light. Analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer from BD Biosciences, using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) counting at least 10,000 events per sample.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Authors would like to acknowledge the financial support for the laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh in part from the NIH R01DA025612, P30DA035778 and P30CA047904.

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01 DA 025612 (X.Q.X.) and NIDA P30DA035778. We thank senior specialist Joanna Stanson for help with the collection and procession of blood samples. RPMI 8226/LR5 cell was provided by Dr. William Dalton (University of South Florida). MM.1S and MM.1R cells were provided by Dr. Klaus Podar (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA).

Abbreviations

- CB2

cannabinoid receptor-2

- MM

multiple myeloma

- PAM

phenylacetylamide

- CHOP

C/EBP homologous protein

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- cAMP

cyclic Adenosine monophosphate

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

Footnotes

Authorship

Contribution: R.F. designed and performed research, analyzed data, wrote and revised the paper; Q.T. and H.C. assisted in performing cell proliferation assay and FCM assay; Z.X. and. L.W. conducted the computer modeling and docking studies; S.L. and G.D.R. provided the test cells and reviewed the paper; X.Q.X. planned and designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote/reviewed the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information is available at the journal website.

References

- 1.Casanova ML, Blazquez C, Martinez-Palacio J, et al. Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:43–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI16116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carracedo A, Gironella M, Lorente M, et al. Cannabinoids induce apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6748–6755. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carracedo A, Lorente M, Egia A, et al. The stress-regulated protein p8 mediates cannabinoid-induced apoptosis of tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarfaraz S, Adhami VM, Syed DN, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Cannabinoids for cancer treatment: progress and promise. Cancer Res. 2008;68:339–342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cudaback E, Marrs W, Moeller T, Stella N. The expression level of CB1 and CB2 receptors determines their efficacy at inducing apoptosis in astrocytomas. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellerito O, Calvaruso G, Portanova P, et al. The synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212–2 sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis by activating p8/CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP)/death receptor 5 (DR5) axis. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:854–863. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang P, Wang L, Xie XQ. Latest advances in novel cannabinoid CB(2) ligands for drug abuse and their therapeutic potential. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:187–204. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashton JC, Wright JL, McPartland JM, Tyndall JD. Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor ligand specificity and the development of CB2-selective agonists. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1428–1443. doi: 10.2174/092986708784567716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A. Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370:1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manera C, Benetti V, Castelli MP, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new 1,8-naphthyridin-4(1H)-on-3-carboxamide and quinolin-4(1H)-on-3-carboxamide derivatives as CB2 selective agonists. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5947–5957. doi: 10.1021/jm0603466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie X-Q, Feng R, Yang P. Novel cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) inverse agonists and therapeutic potential for multiple myeloma and osteoporosis bone diseases. 61/576,041. USA: Vol Patent USSN. 2012

- 15.Podar K, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. Bone marrow microenvironment and the identification of new targets for myeloma therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:10–24. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie X, Chen J, Zhang Y. LIGANDS SPECIFIC FOR CANNABINOID RECEPTOR SUBTYPE 2. WO/2009/058,377. WO Patent. 2009

- 17.Chen JZ, Wang J, Xie* XQ. GPCR structure-based virtual screening approach for CB2 antagonist search. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1626–1637. doi: 10.1021/ci7000814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J-Z, Han X-W, Liu Q, Makriyannis A, Wang J, Xie* X-Q. 3D-QSAR Studies of Arylpyrazole Antagonists of Cannabinoid Receptor Subtypes CB1 and CB2. A Combined NMR and CoMFA Approach. J Med Chem. 2006;49:625–636. doi: 10.1021/jm050655g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie XQ, Chen JZ. Data mining a small molecule drug screening representative subset from NIH PubChem. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:465–475. doi: 10.1021/ci700193u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang P, Myint K-Z, Tong Q, et al. Lead Discovery, Chemistry Optimization, and Biological Evaluation Studies of Novel Biamide Derivatives as CB2 Receptor Inverse Agonists and Osteoclast Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9973–9987. doi: 10.1021/jm301212u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng R, Anderson G, Xiao G, et al. SDX-308, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent, inhibits NF-kappaB activity, resulting in strong inhibition of osteoclast formation/activity and multiple myeloma cell growth. Blood. 2007;109:2130–2138. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-027458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng R, Li S, Lu C, et al. Targeting the microtubular network as a new antimyeloma strategy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1886–1896. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng R, Ni HM, Wang SY, et al. Cyanidin-3-rutinoside, a natural polyphenol antioxidant, selectively kills leukemic cells by induction of oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13468–13476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng R, Oton A, Mapara MY, Anderson G, Belani C, Lentzsch S. The histone deacetylase inhibitor, PXD101, potentiates bortezomib-induced anti-multiple myeloma effect by induction of oxidative stress and DNA damage. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:385–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng Z, Alqarni MH, Yang P, et al. Modeling, molecular dynamics simulation and mutation validation for structure of cannabinoid receptor 2 based on known crystal structures of GPCRs. J Chem Inf Model. 2014 Aug 20; doi: 10.1021/ci5002718. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JZ, Wang J, Xie XQ. GPCR structure-based virtual screening approach for CB2 antagonist search. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1626–1637. doi: 10.1021/ci7000814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng R, Ma H, Hassig CA, et al. KD5170, a novel mercaptoketone-based histone deacetylase inhibitor, exerts antimyeloma effects by DNA damage and mitochondrial signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1494–1505. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alqarni M, Myint KZ, Tong Q, et al. Examining the critical roles of human CB2 receptor residues Valine 3.32 (113) and Leucine 5. 41 (192) in ligand recognition and downstream signaling activities. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Anderson KC. Identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6345–6350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng R, Lu Y, Bowman LL, Qian Y, Castranova V, Ding M. Inhibition of activator protein-1, NF-kappaB, and MAPKs and induction of phase 2 detoxifying enzyme activity by chlorogenic acid. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27888–27895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosier B, Muccioli GG, Hermans E, Lambert DM. Functionally selective cannabinoid receptor signalling: therapeutic implications and opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sluss HK, Davis RJ. H2AX is a target of the JNK signaling pathway that is required for apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Mol Cell. 2006;23:152–153. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W, Yue P, Khuri FR, Sun SY. Coupling of endoplasmic reticulum stress to CDDO-Me-induced up-regulation of death receptor 5 via a CHOP-dependent mechanism involving JNK activation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7484–7492. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamm I, Wang Y, Sausville E, et al. IAP-family protein survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315–5320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strausfeld U, Labbe JC, Fesquet D, et al. Dephosphorylation and activation of a p34cdc2/cyclin B complex in vitro by human CDC25 protein. Nature. 1991;351:242–245. doi: 10.1038/351242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun SY, Hail N, Jr, Lotan R. Apoptosis as a novel target for cancer chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:662–672. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gimenez-Bonafe P, Tortosa A, Perez-Tomas R. Overcoming drug resistance by enhancing apoptosis of tumor cells. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:320–340. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guzman M. Cannabinoids: potential anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrc1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galiegue S, Mary S, Marchand J, et al. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Xie Z, Wang L, et al. Mutagenesis and computer modeling studies of a GPCR conserved residue W5. 43(194) in ligand recognition and signal transduction for CB2 receptor. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rayman N, Lam KH, Laman JD, et al. Distinct expression profiles of the peripheral cannabinoid receptor in lymphoid tissues depending on receptor activation status. J Immunol. 2004;172:2111–2117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez C, de Ceballos ML, Gomez del Pulgar T, et al. Inhibition of glioma growth in vivo by selective activation of the CB(2) cannabinoid receptor. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5784–5789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flygare J, Sander B. The endocannabinoid system in cancer-potential therapeutic target? Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:176–189. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gustafsson K, Christensson B, Sander B, Flygare J. Cannabinoid receptor-mediated apoptosis induced by R(+)-methanandamide and Win55,212-2 is associated with ceramide accumulation and p38 activation in mantle cell lymphoma. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1612–1620. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wada T, Penninger JM. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation. Oncogene. 2004;23:2838–2849. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimberley FC, Screaton GR. Following a TRAIL: update on a ligand and its five receptors. Cell Res. 2004;14:359–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh YT, Liu X, Yue P, et al. ERK/ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) signaling positively regulates death receptor 5 expression through co-activation of CHOP and Elk1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41310–41319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegelin MD, Reuss DE, Habel A, Rami A, von Deimling A. Quercetin promotes degradation of survivin and thereby enhances death-receptor-mediated apoptosis in glioma cells. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:122–131. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lavecchia A, Di Giovanni C, Novellino E. Inhibitors of Cdc25 phosphatases as anticancer agents: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2010;20:405–425. doi: 10.1517/13543771003623232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carvajal RD, Tse A, Schwartz GK. Aurora kinases: new targets for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6869–6875. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mashima T, Naito M, Tsuruo T. Caspase-mediated cleavage of cytoskeletal actin plays a positive role in the process of morphological apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:2423–2430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du J, Wang X, Miereles C, et al. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:115–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson RG, Jr, Tahir SK, Mechoulam R, Zimmerman S, Zimmerman AM. Cannabinoid enantiomer action on the cytoarchitecture. Cell Biol Int. 1996;20:147–157. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure. MAPK inhibitors fail to rescue PAM-induced MM cell death. Human U266 cells were pre-treated with the indicated inhibitors (SP: SP600125 for JNK; U0126 for ERK/MEK; SB: SB203580 for p38 kinase) at indicated doses for 30 min and followed by exposed to PAM (5μM) for another 48 hrs. The cell viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion assay under inverted microscope. Data represent the results of one experiment.

Supplementary Table. PAM treatment slightly increases the polyploidy fraction in the treated MM cells. U266 cells (1× 106) were plated on a 6-well plate in growth medium and treated 24 h after plating with different concentrations of PAM (0–2.5 μM). After treatment, the cells were washed with PBS. The cell pellet resuspended in 3 ml of ice cold ethanol (70% v/v) to fix the cells for overnight at 4°C. For the propidium iodide staining, an aliquot of cells was removed, pelleted and washed with PBS containing 1% fetal bovine serum. Finally, cells were resuspended in 1 ml staining solution [PBS containing 1% (v/v) FBS, 500 μg/ml RNAse (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μg/ml propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen)] and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, while protected from light. Analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer from BD Biosciences, using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) counting at least 10,000 events per sample.