Background: We analyzed the mechanisms mediating osteoblast dysfunctions in cystic fibrosis.

Results: Osteoblast differentiation and function are impaired in ΔF508-CFTR mice due to overactive NF-κB and reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Correcting these pathways rescued the defective osteoblast functions.

Conclusion: Osteoblast dysfunctions in ΔF508-CFTR mice result from altered NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Significance: Targeting the altered signaling pathways can restore osteoblast functions in cystic fibrosis.

Keywords: bone, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), NF-kappa B (NF-kB), osteoblast, Wnt signaling, F508del-CFTR

Abstract

The prevalent human ΔF508 mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is associated with reduced bone formation and bone loss in mice. The molecular mechanisms by which the ΔF508-CFTR mutation causes alterations in bone formation are poorly known. In this study, we analyzed the osteoblast phenotype in ΔF508-CFTR mice and characterized the signaling mechanisms underlying this phenotype. Ex vivo studies showed that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation negatively impacted the differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells into osteoblasts and the activity of osteoblasts, demonstrating that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation alters both osteoblast differentiation and function. Treatment with a CFTR corrector rescued the abnormal collagen gene expression in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts. Mechanistic analysis revealed that NF-κB signaling and transcriptional activity were increased in mutant osteoblasts. Functional studies showed that the activation of NF-κB transcriptional activity in mutant osteoblasts resulted in increased β-catenin phosphorylation, reduced osteoblast β-catenin expression, and altered expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes. Pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB activity or activation of canonical Wnt signaling rescued Wnt target gene expression and corrected osteoblast differentiation and function in bone marrow stromal cells and osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice. Overall, the results show that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation impairs osteoblast differentiation and function as a result of overactive NF-κB and reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Moreover, the data indicate that pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB or activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling can rescue the abnormal osteoblast differentiation and function induced by the prevalent ΔF508-CFTR mutation, suggesting novel therapeutic strategies to correct the osteoblast dysfunctions in cystic fibrosis.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR).2 The main function of the CFTR protein is as a chloride channel in epithelia, and the most common mutation in humans, ΔF508-CFTR, is responsible for a channelopathy in epithelial cells (1). Several studies indicate that cystic fibrosis mutations may impact the skeleton in children and adults. Most patients with cystic fibrosis display low bone mass associated with fractures (2–5). The mechanisms underlying this bone pathology are complex and may involve inflammation and altered physical activity and nutritional status (6). In addition to these general mechanisms, the bone disease in cystic fibrosis may result from abnormal bone cell activity. Bone homeostasis is ensured by a balance between resorption of the bone matrix by osteoclasts and its replacement by new bone formed by osteoblasts (7). Although CFTR was found to be expressed in human osteoclasts and osteoblasts and in mouse osteoblasts (8–10), the impact of CFTR mutations on bone cells remains largely unknown. Genetic studies in Cftr−/− mice have shown that Cftr invalidation causes low bone mass and altered bone microarchitecture, a phenotype associated with decreased bone formation and increased bone resorption (11–15). Others have reported altered osteoblast differentiation in cultured calvarial cells from Cftr−/− mice (10). However, the relevance of the global Cftr invalidation to cystic fibrosis disease resulting from CFTR mutations is not known. Recent studies show that the prevalent ΔF508-CFTR mutation causes reduced bone mass as a result of decreased osteoblast activity and bone formation in mice (16), which may be partially corrected by treatment with a CFTR corrector (17). Although these studies revealed that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation impacts osteogenesis, the molecular mechanisms underlying the defective bone formation induced by the mutation have not been depicted yet.

Previous studies in epithelial cells suggest that CFTR levels may control NF-κB signaling (18–20), albeit the underlying mechanisms are not fully established. Notably, the ΔF508-CFTR mutation is associated with activated NF-κB signaling in lung epithelial cells (21). In bone, exacerbated NF-κB signaling is known to cause inflammation (22) and to promote osteoclastogenesis (23). In addition, recent studies indicate that NF-κB signaling negatively controls bone formation (23–26). Mechanistically, NF-κB activation in osteoblastic cells reduces expression of the key osteogenic transcription factor Runx2 (27) and increases expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Smurf1 (28), resulting in increased proteasomal degradation of RUNX2 (29–32). The potential implication of NF-κB signaling in the abnormal bone formation in cystic fibrosis has not been investigated.

In this study, we analyzed the impact of the prevalent ΔF508-CFTR mutation on the osteoblast phenotype in mice and determined the mechanisms underlying this phenotype. We show here that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation induced defective osteoblast differentiation and function in a cell-autonomous manner as a consequence of increased NF-κB activity and reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling and that targeting these pathways corrected the osteoblast dysfunctions induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation in mice.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Rotterdam homozygous ΔF508-CFTR mice (ΔF508-Cftrtm1Eur), which express the clinically common ΔF508 mutation in the Cftr gene at the wild-type protein level, and their normal Cftr+/+ homozygous littermates (WT mice in the FVB background) were obtained from the Centre de Distribution, Typage et Archivage Animal (CDTA), CNRS (Orléans, France). We used 10-week-old adult male ΔF508-CFTR mice that exhibit decreased bone mass and bone formation related to their normal littermates (16).

Cell Cultures and Treatments

Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were harvested from the left tibias of ΔF508-CFTR and WT mice and cultured as described (33). In addition, osteoblasts were obtained by migration from trabecular bone fragments from long bone metaphysis as described previously (34). Cells at passage 2 were used in the different assays. In some experiments, cells were treated with the CFTR corrector miglustat (10 μm; Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Allschwil, Switzerland) (17), which acts by improving CFTR processing (35). In other experiments, cells were treated with the specific IκB kinase (IKK) inhibitor IKKVI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), which specifically inhibits NF-κB activation (36), at a dose (20 nm) that inhibits the upstream kinase that activates NF-κB (27), or with Wnt3a-conditioned medium (CM; 30%) prepared as described (37).

Proliferation Assay

BMSCs and trabecular osteoblasts isolated from ΔF508-CFTR and WT mice were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. Cell replication was determined using the BrdU ELISA (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Osteoblast Differentiation Assays

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was assayed using an alkaline phosphatase kit (Bio-Rad). For osteogenic differentiation, cell culture medium was supplemented with 50 μmol/liter ascorbic acid and 3 mm inorganic phosphate (NaH2PO4) to allow matrix synthesis and mineralization. At 21 and 28 days of culture, BMSC cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and matrix mineralization was evaluated by alizarin red staining and calcium deposition as described (38).

Reporter Assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and then co-transfected with the reporter plasmid (0.5 μg/well) and phRL-SV40 (10 ng/well; Clontech, Mountain View, CA), a Renilla expression plasmid used as an internal transfection control. Empty pGL3-Basic served as a control for reporter activity. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured sequentially using a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) 48 h after transfection. Luciferase activity was normalized both to Renilla activity, as a transfection control, and to values obtained with cells transfected with empty pGL3-Basic, as control for the variations in phRL-SV40 induced by treatment. Results are expressed as relative luciferase units.

Quantitative PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). One μg of total RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed (Applied Biosystems kit). The relative mRNA levels were evaluated by quantitative PCR analysis (LightCycler, Roche Applied Science) using a SYBR Green PCR kit (ABgene, Courtaboeuf, France) and specific primers (33). Signals were normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase as an internal control.

Western Blot Analysis

Trabecular osteoblasts isolated from ΔF508-CFTR and WT mice were cultured at preconfluence and then treated with Wnt3a-CM (37) for 1 or 24 h. In other experiments, the cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with recombinant mouse TNFα (10 ng/ml; Apotech, Epalinges, Switzerland), and cell lysates were prepared as described (39). Protein concentrations were measured using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Equal aliquots (40–60 μg) of protein extracts were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed using specific primary antibodies raised against β-catenin (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-β-catenin (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p65 (1:1500; a gift from N. Rice, NCI at Frederick, Frederick, MD), phospho-Ser536 p65 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Ozyme, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France), IκBα (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Ser32 IκBα (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), IKKβ (1:1000; Abgent Europe, Maidenhead, United Kingdom), phospho-Ser176/180 IKKα/β (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology), and GAPDH (1:2000; Millipore). Following incubation with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and final washes, the signals were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagent (ECL, Amersham Biosciences) and autoradiography film (X-OMAT-AR, Eastman Kodak Co.). Band intensity at the expected molecular weight was analyzed and expressed as a ratio of treated to control after correction to the housekeeping protein.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on paraffin-embedded histological sections of mouse vertebras using a VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Briefly, after paraffin removal, sections were incubated in citrate buffer at 90 °C for 30 min for antigenic retrieval and treated with hyaluronidase (1 mg/ml; Sigma) at 37 °C for 15 min. Endogenous peroxidase was inhibited by incubating the tissue section in 0.3% H2O2 for 15 min. Tissue sections were incubated with the appropriate serum for 1 h before primary antibody incubation with anti-β-catenin antibody (1:100; clone 247, Fisher Scientific) and revealed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Data are means ± S.D. and represent a pool of three to five individual mice per group or at least six replicates. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance or unpaired two-tailed Student's t test as appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

ΔF508-CFTR Mutation Markedly Reduces Osteoblast Differentiation and Function

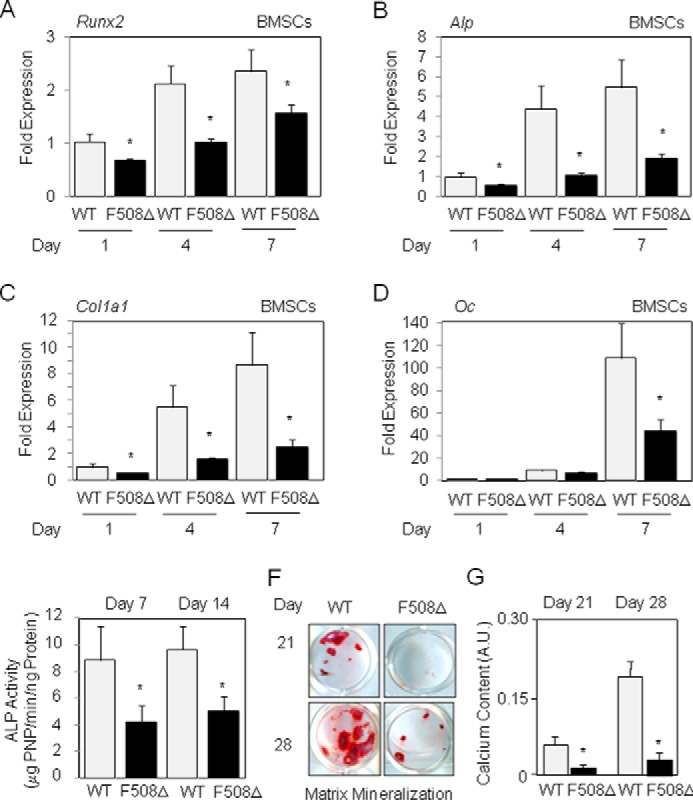

We first determined the impact of the ΔF508-CFTR mutation in BMSCs. In BMSCs from WT mice, early (Runx2, Alp, Col1a1) and late (osteocalcin) phenotypic osteoblast marker genes increased with time in culture (Fig. 1, A–D). We found that the expression of all osteoblast markers was lower in differentiating ΔF508-CFTR BMSCs compared with WT cells (Fig. 1, A–D). This finding was confirmed by the biochemical analysis of ALP activity, which was lower in BMSCs from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 1E). Consistently, the matrix mineralization capacity was lower in ΔF508-CFTR BMSCs compared with WT BMSCs (Fig. 1, F and G), demonstrating the lower than normal capacity of mutant BMSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts.

FIGURE 1.

The ΔF508-CFTR mutation affects osteoblast gene expression in mouse BMSCs. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed decreased expression of osteoblast marker genes in BMSCs isolated from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (A–D). Biochemical analysis demonstrated the decreased ALP activity in BMSCs from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (E). Alizarin red staining (F) and calcium quantification (G) showed the decreased matrix mineralization capacity in long-term cultures of ΔF508-CFTR BMSCs compared with WT cells. Data are means ± S.D. of three to five mice and are reported as changes versus day 1 (A–D). *, significant difference of p < 0.05. Oc, osteocalcin; PNP, p-nitrophenol; A.U., arbitrary units.

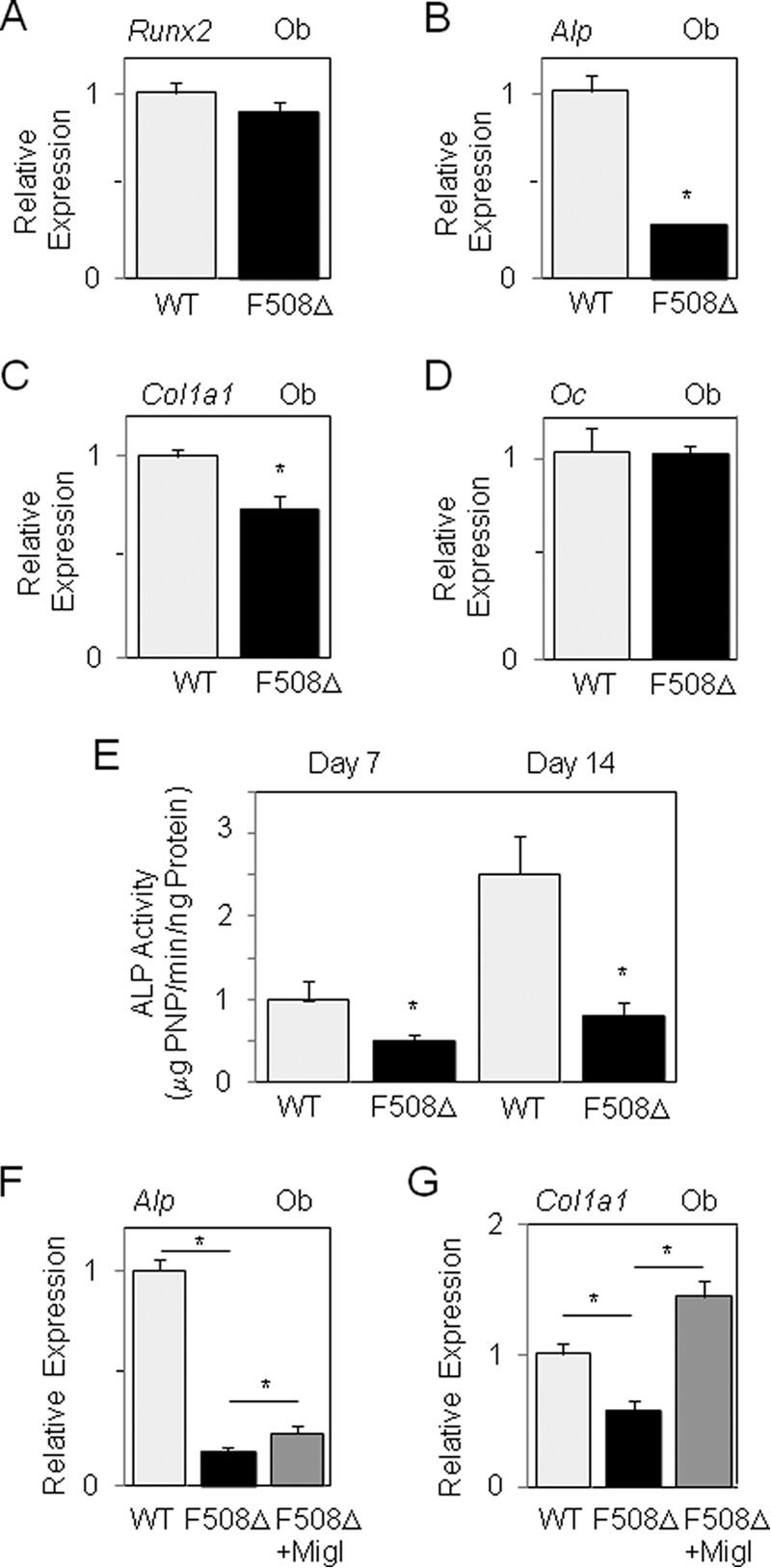

To determine whether the ΔF508-CFTR mutation impacted the function of mature osteoblasts, we analyzed the phenotype of trabecular osteoblasts isolated from marrow-free long bones in mutant mice. We found that Alp and Col1a1 expression (Fig. 2, B and C) and ALP activity (Fig. 2E) were lower in trabecular osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice, whereas Runx2 and osteocalcin expression was not significantly affected in mutant osteoblasts (Fig. 2, A and D), indicating that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation affects cell function in mature osteoblasts. Cell proliferation was not altered in BMSCs or trabecular osteoblasts isolated from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation negatively impacts osteoblast gene expression in BMSCs and reduces the function of trabecular osteoblasts in a cell-autonomous manner. This effect may be related in part to the CFTR mutant because we found that CFTR is expressed at the protein level in both WT and mutant osteoblasts (data not shown), confirming previous analyses (8–10). To analyze whether increasing CFTR levels improve the defective osteoblast function in mutant osteoblasts, we tested the effect of the CFTR corrector miglustat, which was shown to improve ΔF508-CFTR transport to the cell membrane (35). Treatment with the CFTR corrector improved Alp levels and fully corrected Col1a1 expression in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts (Fig. 2, F and G). In contrast, the corrector had no significant effect on expression of these genes in WT osteoblasts (data not shown). These results indicate that the function of ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts can be increased by improving CFTR trafficking to the cell membrane in mutant osteoblasts, which is consistent with our previous finding that treatment with this CFTR corrector improved bone formation in ΔF508-CFTR mice (17).

FIGURE 2.

Decreased osteoblast function in ΔF508-CFTR mice. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed the decreased expression of Alp and Col1a1 mRNA levels in primary osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (A–D). Ex vivo analysis demonstrated the decreased ALP activity in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts compared with WT cells (E). Biochemical analysis showed that the CFTR corrector miglustat (Migl; 10 μm) increased Alp and corrected Col1a1 mRNA levels in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts (F and G). Data are mean ± S.D. of three to five mice. *, significant difference with the indicated group (p < 0.05). Ob, osteoblasts; Oc, osteocalcin.

Osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR Mice Display Increased NF-κB Activity

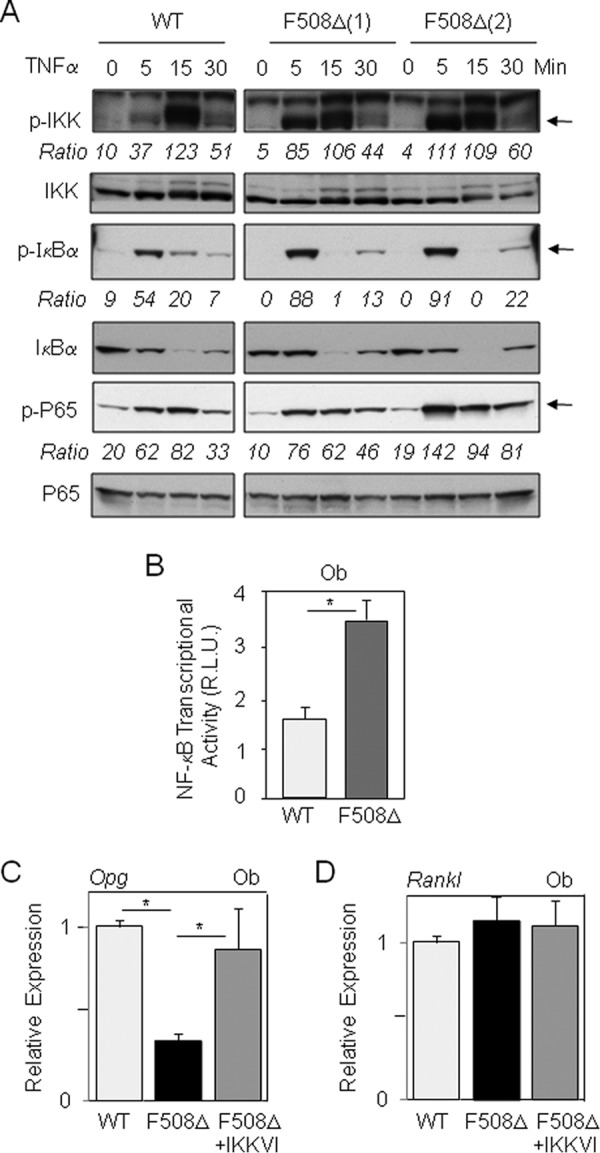

We next determined the signaling mechanisms that may mediate the deleterious effect of the ΔF508-CFTR mutation in osteogenic cells. To this goal, we tested whether the osteoblast dysfunctions in ΔF508-CFTR mutant cells may be linked to abnormal NF-κB activity. The phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα were assessed by Western blot analysis. We found increased levels of phospho-IKK and phospho-IκBα in cell lysates of trabecular osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT cells in response to TNFα at an early time point (5 min) (Fig. 3A). Consistently, phospho-p65 levels were increased in mutant osteoblasts at this time point, suggesting increased NF-κB activity. To confirm this finding, we determined the level of NF-κB transcriptional activity in mutant osteoblasts compared with WT cells under basal conditions. As shown in Fig. 3B, NF-κB transcriptional activity was increased by 2-fold in osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice. These results indicate that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation induces a significant activation of NF-κB activity in osteoblasts.

FIGURE 3.

Overactive NF-κB mediates the osteoblast dysfunctions in ΔF508-CFTR mice. Western blot analysis and quantification showed the relative increase in phosphorylated (p) IKK, IκBα, and p65 protein levels (arrows) in primary osteoblasts (Ob) isolated from two distinct ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice cultured overnight in serum-free medium and treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) (A). Reporter assay demonstrated the constitutive increase in NF-κB transcriptional activity in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts compared with WT cells (B). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed the effect of the specific IκB kinase inhibitor IKKVI (20 nm, 1 day) on the expression of Opg and Rankl mRNA levels in primary osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (C and D). Data are means ± S.D. of three to five mice. *, significant difference with the indicated group (p < 0.05). Ob, osteoblasts; R.L.U., relative luciferase units.

To substantiate the impact of NF-κB signaling in mutant osteoblasts, we analyzed the expression of Opg (osteoprotegerin), an established NF-κB target gene (40) that controls osteoclastogenesis by binding to RANKL (receptor activator of NF-κB ligand) (23). We found that the Opg mRNA level was greatly reduced in osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3C), which is consistent with the observed activation of NF-κB signaling in mutant osteoblasts. In contrast, Rankl expression was not affected in mutant osteoblasts (Fig. 3D). Pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB signaling with the specific IKK inhibitor IKKVI (27, 36) corrected Opg levels with no effect on Rankl expression in mutant osteoblasts (Fig. 3, C and D). Similar results were found in BMSCs from mutant mice, in which both the CFTR corrector miglustat and the IKK inhibitor corrected Opg expression (as shown below). Collectively, these results indicate that the increased NF-κB signaling in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts translates into increased NF-κB target gene expression and that inhibition of NF-κB signaling corrects the altered expression of Opg in mutant osteoblasts.

Increased NF-κB Signaling Leads to Attenuation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in ΔF508-CFTR Osteoblasts

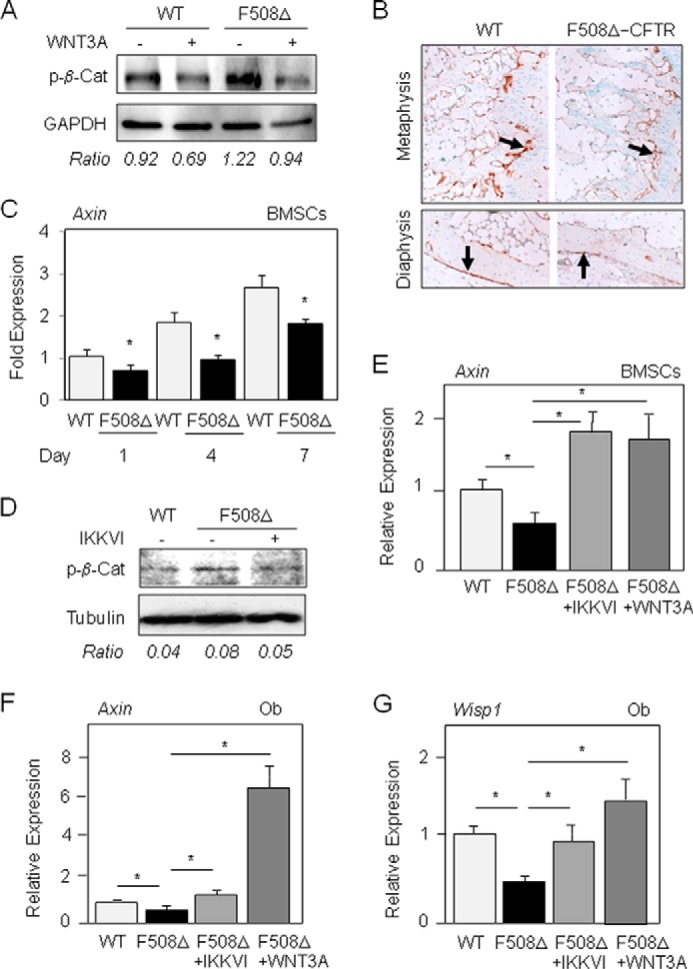

We next determined the mechanism by which activated NF-κB signaling may induce osteoblast dysfunctions in mutant cells. Reduced NF-κB activity was recently found to increase bone formation via enhanced JNK activity and Fra1 expression, suggesting that Fra1 expression may mediate part of the effect of NF-κB signaling in osteoblasts (27). In ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts or BMSCs, we failed to find diminished Fra1 mRNA levels compared with WT cells (data not shown), implying another mechanism causing the osteoblast dysfunctions in mutant cells. Interestingly, NF-κB signaling was recently found to negatively regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mouse osteoblasts (27, 28). Because Wnt/β-catenin signaling is an essential pathway controlling bone formation (41), we hypothesized that the observed NF-κB activation may affect this pathway in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts. To test this hypothesis, in mutant osteoblasts, we analyzed the level of phosphorylated β-catenin, which triggers β-catenin degradation by the proteasome (42). We found that phosphorylated β-catenin levels were higher in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts than in WT cells. Treatment with Wnt3a-CM decreased phosphorylated β-catenin levels in both WT and ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these in vitro data, immunohistochemical analysis performed in vertebral bone revealed higher total β-catenin levels at the metaphyseal and diaphyseal levels in WT osteoblasts compared with ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts (Fig. 4B), indicating decreased β-catenin signaling in mutant osteoblasts in vivo. To determine whether the observed reduction in Wnt/β-catenin signaling was functional in mutant cells, we analyzed the expression of Axin, a direct Wnt target gene (43). The levels of Axin mRNA were decreased in both BMSCs and osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4C). The expression of Wisp1 (Wnt-induced secreted protein 1), a direct marker of canonical Wnt activation (44), was also reduced in mutant BMSCs compared with WT cells (data not shown). Pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB with IKKVI reduced the higher than normal levels of phosphorylated β-catenin levels in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts (Fig. 4D) and corrected the abnormal expression of Axin and Wisp1 in BMSCs and osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice (Fig. 4, E–G). In contrast, the IKK inhibitor had no significant effect in WT osteoblasts (data not shown). Treatment with Wnt3a-CM also greatly increased the expression of Axin and Wisp1 in BMSCs and osteoblasts from ΔF508-CFTR mice (Fig. 4, E–G). These results support a mechanism by which the increased NF-κB signaling induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation leads to attenuated Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Wnt target gene expression in mutant BMSCs and osteoblasts.

FIGURE 4.

The ΔF508-CFTR mutation reduces Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts. Western blot analysis showed higher phospho-β-catenin (p-β-Cat) levels in primary osteoblasts isolated from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice and a normal response to exogenous 30% Wnt3a-CM (A). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated the lower total β-catenin levels (arrows, brown staining) in osteoblasts in the metaphysis and diaphysis of vertebras from 10-week-old ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with age-matched WT mice (B). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed reduced expression of the Wnt-responsive gene Axin in primary BMSCs from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (C). Western blot analysis showed that the IκB kinase inhibitor IKKVI (20 nm, 24 h) corrected phospho-β-catenin levels in primary osteoblasts isolated from ΔF508-CFTR mice (D). Treatment with IKKVI (20 nm) or Wnt3a-CM (30%) corrected Wnt target gene expression in mutant BMSCs (E) and osteoblasts (Ob) (F and G). Data are means ± S.D. of five mice. *, significant difference with the indicated group (p < 0.05).

Inhibition of NF-κB or Activation of Wnt Signaling Rescues Altered Osteoblast Differentiation and Function in ΔF508-CFTR Cells

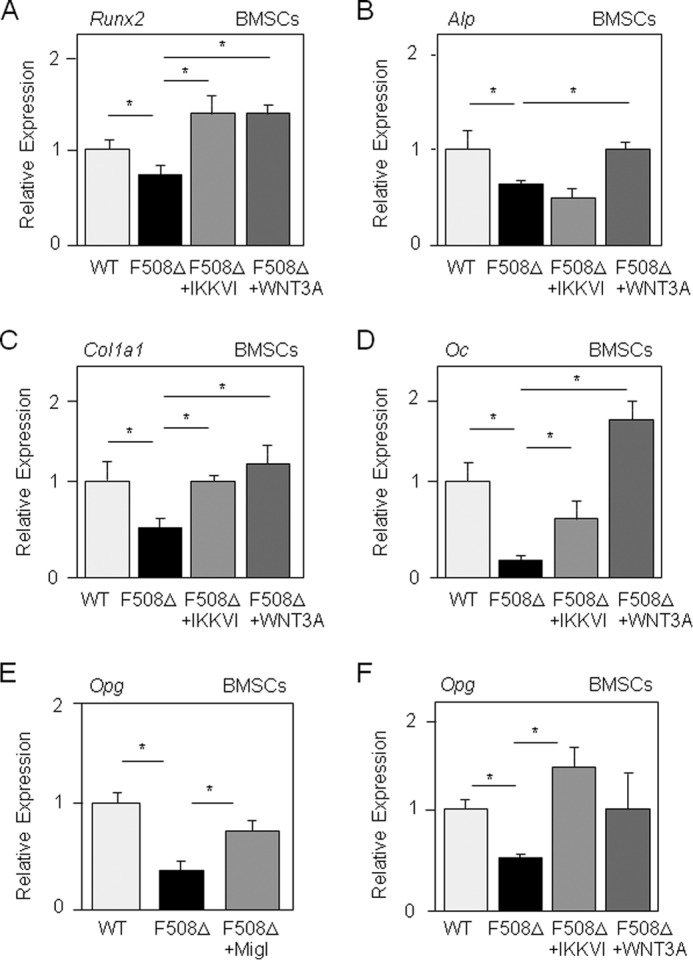

We then determined the functional implication of the altered NF-κB and Wnt signaling in the altered osteoblast gene expression in mutant BMSCs. We found that the IKK inhibitor increased Runx2, Col1a1, and osteocalcin levels, with no significant change in Alp expression, whereas treatment with Wnt3a-CM fully corrected osteoblast gene expression in mutant BMSCs (Fig. 5, A–D). These data indicate that the reduced osteoblast gene expression induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation in BMSCs is improved by inhibition of NF-κB signaling and is rescued by activation of canonical Wnt signaling. Both the CFTR corrector miglustat and IKKVI corrected expression of the NF-κB target gene Opg in ΔF508-CFTR BMSCs (Fig. 5, E and F), supporting a link among the ΔF508-CFTR mutation, activation of NF-κB signaling, and decreased Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mutant BMSCs.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of NF-κB signaling or stimulation of Wnt signaling rescues osteoblast gene expression and Opg expression in BMSCs. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated the effect of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKKVI (20 nm) and Wnt3a-CM (30%) on the expression of osteoblast genes in BMSCs from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (A–D). Opg, a NF-κB target gene, was corrected by the CFTR corrector miglustat (Migl; 10 μm) and by IKKVI in ΔF508-CFTR BMSCs (E and F). Data are means ± S.D. of five mice. *, significant difference with the indicated group (p < 0.05). Oc, osteocalcin.

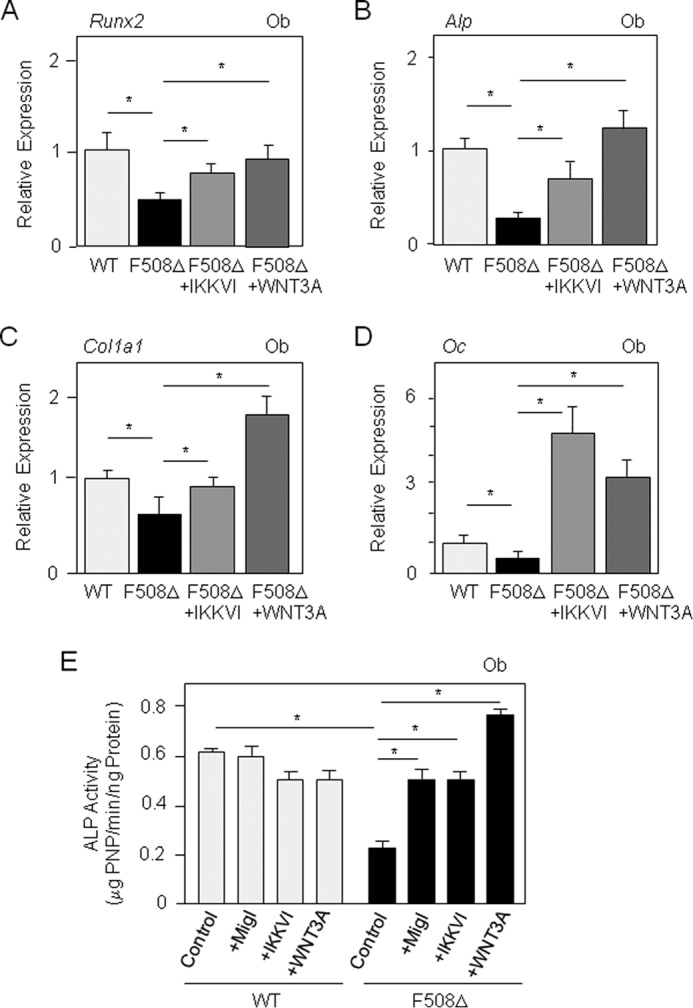

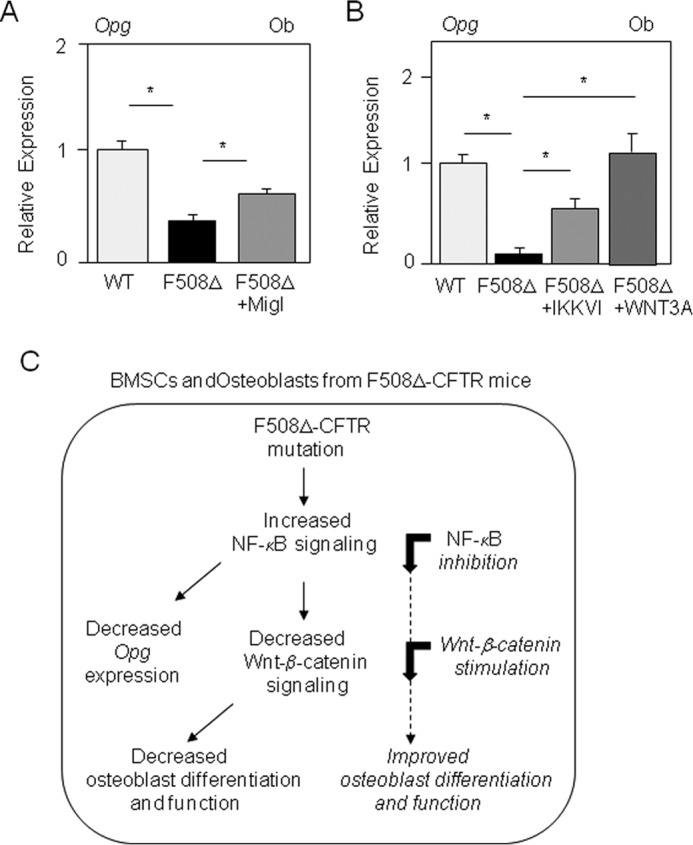

To determine the impact of the altered NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in more mature osteoblasts, we analyzed whether the osteoblast dysfunction in mutant mice may be rescued by NF-κB inhibition or Wnt3a stimulation. The IKK inhibitor greatly increased the expression of all osteoblast marker genes in mutant osteoblasts, and treatment with Wnt3a-CM fully corrected the expression of differentiation markers in mutant osteoblasts (Fig. 6, A–D). Moreover, functional long-term analysis showed that ALP activity was restored to normal levels in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts after 14 days of treatment with miglustat, IKKVI, or Wnt3a (Fig. 6E), which confirmed the effect of these treatments on osteoblast markers. In addition to these effects on osteoblast function, the CFTR corrector miglustat, the IKK inhibitor, or Wnt3a-CM increased Opg levels in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts (Fig. 7, A and B). No significant effect of the IKK inhibitor or CFTR corrector on these genes was observed in WT osteoblasts, in contrast to Wnt3a (data not shown). Overall, the results indicate that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation, in a cell-autonomous manner, causes a phenotype characterized by inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and function as the consequence of overactive NF-κB signaling and attenuated Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Consistent with these findings, the osteoblast dysfunctions induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation were rescued by pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB or activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 6.

Rescue of osteoblast functions in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that IKKVI (20 nm) or Wnt3a-CM (30%) corrected the expression of osteoblast marker genes in primary osteoblasts (Ob) from ΔF508-CFTR mice compared with WT mice (A–D). Functional assay showed that the reduced ALP activity in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts was corrected by miglustat (10 μm), IKKVI (20 nm), or Wnt3a-CM (30%) in long-term culture (14 days) (E). Data are means ± S.D. of three to five mice. *, significant difference with the indicated group (p < 0.05). Oc, osteocalcin; PNP, p-nitrophenol.

FIGURE 7.

Mechanisms mediating osteoblast dysfunctions in ΔF508-CFTR mice. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that the reduced Opg levels in primary osteoblasts (Ob) from ΔF508-CFTR mice were increased by miglustat (Migl; 10 μm) (A) or by IKKVI (20 nm) or Wnt3a-CM (30%) (B). Shown is C is the proposed mechanism by which the ΔF508-CFTR mutation leads to overactive NF-κB signaling in murine BMSCs and mature osteoblasts, resulting in reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling and decreased osteoblast differentiation and function. Pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB or activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling rescued osteoblast dysfunctions induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation, suggesting novel therapeutic strategies to correct the osteoblast abnormalities in cystic fibrosis.

Discussion

In this study, we identified the molecular mechanisms by which the prevalent ΔF508-CFTR mutation negatively impacts osteoblast differentiation and function in a murine model of cystic fibrosis that is relevant to the human disease. By analyzing the phenotype of osteoblast precursor cells and mature osteoblasts isolated from ΔF508-CFTR mice, we showed that the mutation severely decreased osteoblast gene expression and osteogenic function, whereas cell proliferation was not affected. Importantly, the ΔF508-CFTR mutation in mice affected osteoblast differentiation and function ex vivo, indicating that these osteoblast dysfunctions occur independently of the environmental, nutritional, inflammatory, or hormonal status.

Having characterized the osteoblast abnormalities in ΔF508-CFTR mice, we analyzed the signaling mechanisms that underlie these osteoblast dysfunctions. We found that NF-κB signaling was overactive in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts, which is consistent with the previously reported overactive NF-κB signaling in lung epithelial cells in cystic fibrosis (21, 45). Our finding that the expression of Opg, an established target of NF-κB signaling (40), was reduced in mutant osteoblasts and restored by NF-κB inhibition further indicates that NF-κB signaling is overactive in mutant osteoblasts. The increased NF-κB signaling was functional because pharmacological NF-κB inhibition attenuated the abnormal expression of most osteoblast differentiation markers in both mutant BMSCs and mature osteoblasts and restored osteoblast function evaluated by ALP activity. These data indicate that the overactive NF-κB induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation functionally contributes to the reduced osteoblast gene expression in BMSCs and to the defective osteoblast function in mutant mice.

The mechanisms by which CFTR mutations activate NF-κB signaling in epithelial cells are not fully understood (19, 20). It was proposed that the altered transport of ΔF508-CFTR to the cell membrane and the subsequent decrease in CFTR at the epithelial cell surface results in increased NF-κB signaling (20). Consistently, overexpression of wild-type CFTR was shown to suppress NF-κB-driven signaling in epithelial cells (45). In line with this concept, we found here that treatment with a CFTR corrector, which can improve ΔF508-CFTR transport to the cell membrane in epithelial cells (35), corrected both Opg and Col1a1 expression in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts. These results support a link among the levels of CFTR at the cell membrane, NF-κB activity, and osteoblast function in mutant cells. We then determined the mechanism by which NF-κB activation may induce osteoblast dysfunctions in ΔF508-CFTR cells. Up to now, few NF-κB target genes have been identified in osteoblasts (24). One potential NF-κB target gene is Fra1, which is an essential regulator of bone formation (46). We did not find reduced Fra1 mRNA levels in osteoblasts or BMSCs from ΔF508-CFTR mice, suggesting that other mechanisms mediate osteoblast dysfunctions in mutant mice. Interestingly, several cross-talks were found between the NF-κB and Wnt signaling pathways (47). In osteoblasts, NF-κB signaling was found to inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling (27, 28), in part via increased Smurf1 expression, resulting in increased β-catenin proteasomal degradation (28). We found that ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts displayed increased phospho-β-catenin levels, a mechanism that leads to β-catenin degradation (43), and exhibited lower than normal total β-catenin in vivo, indicating decreased canonical Wnt signaling. In support of these findings, Axin, a direct Wnt target gene, was down-regulated in ΔF508-CFTR BMSCs and osteoblasts compared with WT cells. Consistent with a pathogenic role of decreased Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mutant cells, we found that Wnt3a fully rescued the expression of Wnt target genes in ΔF508-CFTR osteoblasts. Consequently, Wnt signaling activation by Wnt3a rescued both the defective osteoblast gene expression in BMSCs and the abnormal function evaluated by ALP activity in more mature trabecular osteoblasts. These results support an essential role of activated NF-κB and decreased Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the altered osteoblast differentiation and function induced by the ΔF508-CFTR mutation and indicate that the osteoblast dysfunctions in mutant cells can be corrected by targeting these aberrant signaling pathways (Fig. 7C).

In summary, our results indicate that the ΔF508-CFTR mutation causes inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and function in a cell-autonomous manner as a result of overactive NF-κB and reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In addition to identification of a pathogenic role of NF-κB and Wnt signaling in the altered osteoblast differentiation and function induced by the prevalent ΔF508-CFTR mutation in mice, our data suggest that targeting the NF-κB or Wnt signaling pathway may be an efficient therapeutic strategy to rescue the altered osteoblast function responsible for the decreased bone formation and osteopenia in cystic fibrosis.

Author Contributions

C. L. H. and P. J. M. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. C. L. H., R. F., D. M., M. Z., V. G., C. M., N. T., and E. L. designed and performed or helped to design and analyze the experiments. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Jaquot (EA 4691, FED 4231, Reims, France) and the Centre de Distribution, Typage et Archivage Animal (CDTA), CNRS, for the ΔF508-CFTR mice.

This work was supported by grants from the Association Prévention and Traitement des Décalcifications and the Association Rhumatisme et Travail (to P. J. M.), Paris, France, and by Grant RF20110600482 from Vaincre La Mucoviscidose (VLM 2012–2013, to C. L. H.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- CFTR

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- BMSC

- bone marrow stromal cell

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- CM

- conditioned medium

- ALP

- alkaline phosphatase.

References

- 1. Edelman A., Saussereau E. (2012) Cystic fibrosis and other channelopathies. Arch. Pediatr. 19, Suppl. 1, S13–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haworth C. S., Selby P. L., Webb A. K., Dodd M. E., Musson H., Niven R., Economou G., Horrocks A. W., Freemont A. J., Mawer E. B., Adams J. E. (1999) Low bone mineral density in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 54, 961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Conway S. P., Morton A. M., Oldroyd B., Truscott J. G., White H., Smith A. H., Haigh I. (2000) Osteoporosis and osteopenia in adults and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: prevalence and associated factors. Thorax 55, 798–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sermet-Gaudelus I., Souberbielle J. C., Ruiz J. C., Vrielynck S., Heuillon B., Azhar I., Cazenave A., Lawson-Body E., Chedevergne F., Lenoir G. (2007) Low bone mineral density in young children with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175, 951–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paccou J., Zeboulon N., Combescure C., Gossec L., Cortet B. (2010) The prevalence of osteoporosis, osteopenia, and fractures among adults with cystic fibrosis: a systematic literature review with meta-analysis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 86, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Legroux-Gérot I., Leroy S., Prudhomme C., Perez T., Flipo R. M., Wallaert B., Cortet B. (2012) Bone loss in adults with cystic fibrosis: prevalence, associated factors, and usefulness of biological markers. Joint Bone Spine 79, 73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raggatt L. J., Partridge N. C. (2010) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25103–25108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shead E. F., Haworth C. S., Condliffe A. M., McKeon D. J., Scott M. A., Compston J. E. (2007) Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is expressed in human bone. Thorax 62, 650–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bronckers A., Kalogeraki L., Jorna H. J., Wilke M., Bervoets T. J., Lyaruu D. M., Zandieh-Doulabi B., Denbesten P., de Jonge H. (2010) The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is expressed in maturation stage ameloblasts, odontoblasts and bone cells. Bone 46, 1188–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stalvey M. S., Clines K. L., Havasi V., McKibbin C. R., Dunn L. K., Chung W. J., Clines G. A. (2013) Osteoblast CFTR inactivation reduces differentiation and osteoprotegerin expression in a mouse model of cystic fibrosis-related bone disease. PLoS ONE 8, e80098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dif F., Marty C., Baudoin C., de Vernejoul M. C., Levi G. (2004) Severe osteopenia in CFTR-null mice. Bone 35, 595–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guilbault C., Saeed Z., Downey G. P., Radzioch D. (2007) Cystic fibrosis mouse models. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haston C. K., Li W., Li A., Lafleur M., Henderson J. E. (2008) Persistent osteopenia in adult cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-deficient mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177, 309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pashuck T. D., Franz S. E., Altman M. K., Wasserfall C. H., Atkinson M. A., Wronski T. J., Flotte T. R., Stalvey M. S. (2009) Murine model for cystic fibrosis bone disease demonstrates osteopenia and sex-related differences in bone formation. Pediatr. Res. 65, 311–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paradis J., Wilke M., Haston C. K. (2010) Osteopenia in Cftr-ΔF508 mice. J. Cyst. Fibros. 9, 239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Henaff C., Gimenez A., Haÿ E., Marty C., Marie P., Jacquot J. (2012) The F508del mutation in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene impacts bone formation. Am. J. Pathol. 180, 2068–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Le Henaff C., Haÿ E., Velard F., Marty C., Tabary O., Marie P. J., Jacquot J. P. (2014) Enhanced F508del-CFTR channel activity ameliorates bone pathology in murine cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 1132–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borot F., Vieu D. L., Faure G., Fritsch J., Colas J., Moriceau S., Baudouin-Legros M., Brouillard F., Ayala-Sanmartin J., Touqui L., Chanson M., Edelman A., Ollero M. (2009) Eicosanoid release is increased by membrane destabilization and CFTR inhibition in Calu-3 cells. PLoS ONE 4, e7116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vij N., Mazur S., Zeitlin P. L. (2009) CFTR is a negative regulator of NFκB mediated innate immune response. PLoS ONE 4, e4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bodas M., Vij N. (2010) The NF-κB signaling in cystic fibrosis lung disease: pathophysiology and therapeutic potential. Discov. Med. 9, 346–356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tabary O., Boncoeur E., de Martin R., Pepperkok R., Clément A., Schultz C., Jacquot J. (2006) Calcium-dependent regulation of NF-κB activation in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell. Signal. 18, 652–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pacifici R. (2010) The immune system and bone. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 503, 41–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boyce B. F., Yao Z., Xing L. (2010) Functions of nuclear factor-κB in bone. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1192, 367–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krum S. A., Chang J., Miranda-Carboni G., Wang C. Y. (2010) Novel functions for NFκB: inhibition of bone formation. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 607–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novack D. V. (2011) Role of NF-κB in the skeleton. Cell Res. 21, 169–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weitzmann M. N. (2013) The role of inflammatory cytokines, the RANKL/OPG axis, and the immunoskeletal interface in physiological bone turnover and osteoporosis. Scientifica 2013, 125705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang J., Wang Z., Tang E., Fan Z., McCauley L., Franceschi R., Guan K., Krebsbach P. H., Wang C. Y. (2009) Inhibition of osteoblastic bone formation by nuclear factor-κB. Nat. Med. 15, 682–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang J., Liu F., Lee M., Wu B., Ting K., Zara J. N., Soo C., Al Hezaimi K., Zou W., Chen X., Mooney D. J., Wang C. Y. (2013) NF-κB inhibits osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by promoting beta-catenin degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9469–9474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhao M., Qiao M., Oyajobi B. O., Mundy G. R., Chen D. (2003) E3 ubiquitin ligase Smurf1 mediates core-binding factor α1/Runx2 degradation and plays a specific role in osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27939–27944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao M., Qiao M., Harris S. E., Oyajobi B. O., Mundy G. R., Chen D. (2004) Smurf1 inhibits osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12854–12859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaneki H., Guo R., Chen D., Yao Z., Schwarz E. M., Zhang Y. E., Boyce B. F., Xing L. (2006) Tumor necrosis factor promotes Runx2 degradation through up-regulation of Smurf1 and Smurf2 in osteoblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4326–4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guo R., Yamashita M., Zhang Q., Zhou Q., Chen D., Reynolds D. G., Awad H. A., Yanoso L., Zhao L., Schwarz E. M., Zhang Y. E., Boyce B. F., Xing L. (2008) Ubiquitin ligase Smurf1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-induced systemic bone loss by promoting proteasomal degradation of bone morphogenetic signaling proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23084–23092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haÿ E., Laplantine E., Geoffroy V., Frain M., Kohler T., Müller R., Marie P. J. (2009) N-cadherin interacts with axin and LRP5 to negatively regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling, osteoblast function, and bone formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 953–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Modrowski D., Marie P. J. (1993) Cells isolated from the endosteal bone surface of adult rats express differentiated osteoblastic characteristics in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 271, 499–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Becq F. (2010) Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators for personalized drug treatment of cystic fibrosis: progress to date. Drugs 70, 241–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park B. K., Zhang H., Zeng Q., Dai J., Keller E. T., Giordano T., Gu K., Shah V., Pei L., Zarbo R. J., McCauley L., Shi S., Chen S., Wang C. Y. (2007) NF-κB in breast cancer cells promotes osteolytic bone metastasis by inducing osteoclastogenesis via GM-CSF. Nat. Med. 13, 62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haÿ E., Faucheu C., Suc-Royer I., Touitou R., Stiot V., Vayssière B., Baron R., Roman-Roman S., Rawadi G. (2005) Interaction between LRP5 and Frat1 mediates the activation of the Wnt canonical pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13616–13623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miraoui H., Oudina K., Petite H., Tanimoto Y., Moriyama K., Marie P. J. (2009) Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 promotes osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal cells via ERK1/2 and protein kinase C signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4897–4904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Laplantine E., Fontan E., Chiaravalli J., Lopez T., Lakisic G., Véron M., Agou F., Israël A. (2009) NEMO specifically recognizes K63-linked polyubiquitin chains through a new bipartite ubiquitin-binding domain. EMBO J. 28, 2885–2895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li X., Massa P. E., Hanidu A., Peet G. W., Aro P., Savitt A., Mische S., Li J., Marcu K. B. (2002) IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ are each required for the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response program. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45129–45140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baron R., Kneissel M. (2013) WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 19, 179–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nusse R. (2005) Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 15, 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Clevers H. (2006) Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Longo K. A., Kennell J. A., Ochocinska M. J., Ross S. E., Wright W. S., MacDougald O. A. (2002) Wnt signaling protects 3T3-L1 preadipocytes from apoptosis through induction of insulin-like growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38239–38244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hunter M. J., Treharne K. J., Winter A. K., Cassidy D. M., Land S., Mehta A. (2010) Expression of wild-type CFTR suppresses NF-κB-driven inflammatory signalling. PLoS ONE 5, e11598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eferl R., Hoebertz A., Schilling A. F., Rath M., Karreth F., Kenner L., Amling M., Wagner E. F. (2004) The Fos-related antigen Fra-1 is an activator of bone matrix formation. EMBO J. 23, 2789–2799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Du Q., Geller D. A. (2010) Cross-regulation between Wnt and NF-κB signaling pathways. For Immunopathol. Dis. Therap. 1, 155–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]