Background: Mechanistic information regarding how lead exposure decreases bone mass does not exist in the literature.

Results: Pb exposure decreases bone formation and inhibits Wnt signaling; this effect is mitigated by the deletion of sclerostin.

Conclusion: Pb inhibition of the Wnt pathway impedes osteoblast activity and is mediated by blockade of the TGFβ/Smad3 pathway.

Significance: This study provides insight regarding Pb suppression of bone-forming activity.

Keywords: bone, gene expression, osteoblast, osteoporosis, Wnt signaling, lead toxicity, TGF-β signaling, sclerostin

Abstract

Exposure to lead (Pb) from environmental sources remains an overlooked and serious public health risk. Starting in childhood, Pb in the skeleton can disrupt epiphyseal plate function, constrain the growth of long bones, and prevent attainment of a high peak bone mass, all of which will increase susceptibility to osteoporosis later in life. We hypothesize that the effects of Pb on bone mass, in part, come from depression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, a critical anabolic pathway for osteoblastic bone formation. In this study, we show that depression of Wnt signaling by Pb is due to increased sclerostin levels in vitro and in vivo. Downstream activation of the β-catenin pathway using a pharmacological inhibitor of GSK-3β ameliorates the Pb inhibition of Wnt signaling activity in the TOPGAL reporter mouse. The effect of Pb was determined to be dependent on sclerostin expression through use of the SOST gene knock-out mice, which are resistant to Pb-induced trabecular bone loss and maintain their mechanical bone strength. Moreover, isolated bone marrow cells from the sclerostin null mice show improved bone formation potential even after exposure to Pb. Also, our data suggest that the TGFβ canonical signaling pathway is the mechanism by which Pb controls sclerostin production. Taken together these results support our hypothesis that the osteoporotic-like phenotype observed after Pb exposure is, in part, regulated through modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Introduction

Elevated lead (Pb) exposure remains a public health concern in the United States and throughout the world. Many older homes and inner city residences persist with Pb contamination, resulting in continued cases of preventable Pb poisoning. The musculoskeletal system contains the body's greatest Pb burden, yet the adverse effects of Pb on bone have only recently become more appreciated. Published observations suggest that this Pb burden contributes to an osteoporotic-like phenotype in aging rodents through a skeletal-wide decrease in bone mass (1, 2).

Historically, there have been numerous studies describing a negative effect of Pb on bone formation. The heavy metal has been shown to reduce the activity of bone-forming osteoblasts through inhibition of osteonectin secretion, decreasing alkaline phosphatase activity, and depressing type I collagen synthesis (3, 4). Osteoblast proliferation and response from growth factors are also reduced (5, 6).

Osteoblasts arise from committed osteoprogenitor mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).2 Their growth and differentiation are regulated by endogenous and environmental factors. Two key pathways involved in the maturation of these stem cells are the Runx2 and Wnt/β-catenin pathways, which promote osteogenesis and direct in vitro bone nodule formation (7, 8). Initiation of Wnt signaling occurs through disassociation of the negative regulating complex GSK-3/APC (glycogen synthase kinase 3/adenomatosis polyposis coli), allowing for activation of β-catenin (9). Because the Wnt pathway is essential for bone formation and Pb suppresses osteoblast activity, the mechanism to Pb impingement upon the signaling pathway is investigated.

Pb depression of Wnt signaling may be mediated by an increase in the secreted Wnt signaling antagonist sclerostin. Sclerostin is a product of the SOST gene and has recently been characterized as a critical molecule regulating bone mass through inhibition of the LRP5/6 receptor (10). Indeed, anti-sclerostin therapy has been demonstrated to effectively treat osteoporotic-like bone loss (11) and increase bone mineral density (12).

Our main objective in this study was to determine whether Pb inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling via sclerostin is sufficient to depress bone formation and decrease bone mass. In initial experiments using Wnt signaling reporter mice, we used a pharmacologic downstream activator (i.e. GSK-3β inhibitor 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO)) to show that the predominant effect of Pb is at the level of Wnt receptor activation. We exposed mice that are deficient in the SOST gene to Pb and showed that these animals are resistant to the bone loss observed in wild-type mice. Along with this, we evaluated the bone-forming potential of marrow cells from sclerostin knock-out (SOST-KO) mice as compared with WT after Pb exposure.

Experimental Procedures

Osteoblast Cell Culture

We isolated osteoblasts from neonatal mouse calvaria as described previously (13). Briefly, we utilized calvaria from 2-day-old pups and collected bone cells by sequential digestion with collagenase I enzyme in Opti-MEM (Gibco). Cells were plated in normal low-glucose α-minimum essential medium (Sigma) with 10% FBS, 50 μg/ml ascorbate, and 10 mm β-glycerol phosphate (osteogenic medium) to promote osteoblast differentiation and mineralization (14). Cells were also treated with increasing concentrations of Pb, recombinant sclerostin, and/or Wnt3a (R&D Systems). Bone nodule formation was assessed after 10 and 20 days in culture by alkaline phosphatase (nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) substrate, Thermo Scientific) and 0.1% alizarin red (95% ethanol; Sigma) staining.

Western Blot and Quantitative Real-time PCR

We collected total cellular protein from primary osteoblasts and osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Nuclear extracts were achieved using the NE-PER extraction kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Thermo Fisher). Protein was fractionated by 7.5–12% SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with either an anti-sclerostin or an anti-dickkopf (DKK1), both from R&D Systems; anti-active (unphosphorylated) β-catenin (ABC; Millipore); anti-Smad3 and anti-phosho-smad3 (pSmad3; Cell Signaling), anti-histone 3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-β actin (Oncogene Research Products) antibody for 2 h. After washing, membranes were incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h. Bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) and autoradiography film.

We collected total RNA from primary osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells following treatment with Pb, TGFβ1 (R&D Systems), or the inhibitor TGFβ RI-V#616456 (Calbiochem). RNA was purified using Qiagen mini columns. Reverse transcription was then performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit from Bio-Rad, and quantitative PCR reactions were carried out using PerfeCTa SYBR Green (Quanta) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Genes of interest were normalized to β-actin expression.

Luciferase Assays

Initially, MC3T3-E1 cells were plated and transfected with TOPFLASH (LEF/TCF basal c-Fos-luciferase), human 7-kb sclerostin upstream promoter (SOST-Luc) (15), Smad3 reporter (p3TP-lux), or constructively active Smad3 construct (CA-Smad3) (16). Then, transfections were performed using FuGENE HD (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and as described previously (17). 24 h after transfection, the cells were exposed to various treatments; 48 h later, cells were lysed and protein extracts were prepared using the Dual-Luciferase assay system (Promega). Finally, luminescence was quantified in the extracts with an Optocomp luminometer (MGM Instruments).

TOPGAL Cellular Activity Assay

We obtained TOPGAL transgenic mice from The Jackson Laboratory. Reporter mice contain the transgene lacZ under control of a regulatory sequence consisting of three consensus LEF/TCF-binding motifs (18, 19). Bone marrow cells were isolated from femora and tibia of genotypically positive TOPGAL mice by flushing the diaphyses with a 22-gauge needle with α-minimum essential medium. Cellular aspirates were allowed to settle for 5 days before experimentation. Then, cells were treated for 48 h with either 75 ng/ml Wnt3a or 1 μm BIO (GSK3 inhibitor, Calbiochem) in the presence or absence of Pb. Cells were either harvested for sclerostin expression or β-galactosidase protein activity or fixed with 0.2% glutaraldehyde and stained for X-gal activity. A chemiluminescent substrate was used for determining β-galactosidase activity, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech).

Genetic Animal Models and Pb Exposure

Pregnant SOST-KO mice (20) and wild-type controls were divided into three groups to receive water containing 0, 50, or 200 ppm of Pb acetate at postnatal day 1. The Pb exposure was continued in male offspring after weaning. At 3 months of age, serum and whole blood samples from 24-h-fasted mice were collected. Bone Pb was determined by atomic absorption. We measured femur length from the greater trochanter to the medial condyle using a mechanical sliding caliper.

Generation of the TGFβ type 2 receptorflox/flox (TβRIIf/f) has been described previously (21). These mice were crossed with the collagen 1a1 cre mouse (The Jackson Laboratory) to produce osteoblast-specific deletion of the receptor. Mutated mice with a targeted disruption of Smad3 exon 8 (22) (Smad3−/−) were also used to assess sclerostin expression and regulation.

ELISA Assays and FACS Analysis

We measured the serum bone formation marker type 1 procollagen (P1NP), bone resorption marker type 1 C-terminal telopeptide (CTX-1), and osteoclast activity by P1NP ELISA, RatLapsTM ELISA, and TRAP5b, respectively, from Nordic Biosciences Diagnostic. We measured serum levels of sclerostin (ALPCO Diagnostics), corticosterone (IDS), and DKK1 (R&D Systems) using standard ELISA methods according to procedures provided by the manufacturer.

Bone marrow was harvested from 3-month-old WT and SOST-KO mice. Cells were incubated with antibody-conjugated microbeads for Sca-1, CD43, CD45, and CD11b (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MSC populations were identified for positive expression of Sca-1 and negative expression of CD43, CD45 and CD11b.

Microcomputed Tomography (microCT) and Biomechanics

We probed lumbar vertebrae 4 of 6-month-old mice on a VivaCT40 microCT scanner (Scanco Medical) using an integration time of 300 ms, energy of 55 peak kilovoltage, and intensity of 145 μA. Images were reconstructed to an isotropic voxel size of 15 μm. We selected all the trabecular bone within the vertebral body, and segmented trabecular bone from the cortex using a semi-automated contouring algorithm in the axial plane. Then, four lumbar vertebrae specimens were prepared for strength testing using a low-speed diamond saw to remove posterior elements and endplates. Bones were embedded in 0.5 mm of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement at the endplates using a custom jig to ensure even axial alignment and load distribution. Vertebral bodies were compressed to failure at a displacement rate of 3 mm/min (Instron 4465/5500). Structural parameters of maximum load, stiffness, and energy absorption data were generated from the load-displacement curve for each specimen.

In Vivo Osteoclastogenesis and Osteogenesis Assay

We obtained bone marrow from 3-month-old male WT and SOST-KO mice. For osteoclast formation assays, cells were cultured in 10% FBS α-minimum essential medium with conditioned medium from an M-CSF-producing cell line (1:50) and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL, 10 ng/ml, R&D Systems) for 5–7 days as described previously (23). TRAP staining was conducted, and positive osteoclasts were counted. Also, bone marrow cells were treated with osteogenic medium, and the progression of bone nodule formation by alkaline phosphatase staining on day 14 was determined.

Sclerostin Immunostaining

Tibias were harvested from wild-type and genetically modified mice at 2–3 months of age. Bones were fixed, processed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained as described previously (1). We performed sclerostin immunohistochemical staining on three tissue sections per group. Briefly, we used 1:100 anti-sclerostin primary antibody and then either i) incubated with rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody (1:500) and then horseradish peroxide streptavidin (1:750) and developed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole chromogen or ii) incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat secondary antibody, all from Life Technologies.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± S.E. The differences between the groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance between groups (analysis of variance), and comparison of genotypes (WT versus KO) and vehicle versus BIO/Wnt treatment using two-way analysis of variance. p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Pb Inhibits Osteogenesis, and Wnt Mitigates the Effect

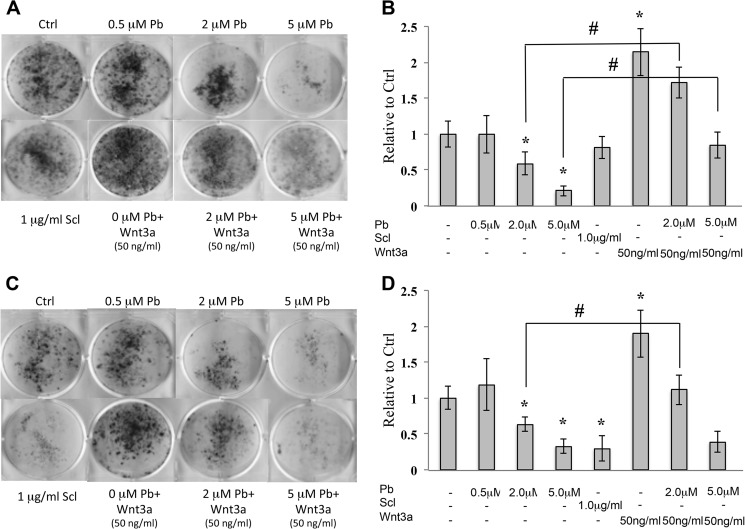

Pb inhibited bone nodule formation of mouse calvarial osteoblasts in a dose-dependent manner. Fig. 1, A and C, show that there is a reduction in alkaline phosphatase nodule staining (−25% at 2 μm; −68% at 5 μm) and alizarin red nodule staining (−38% at 2 μm; −71% at 5 μm) as compared with controls (these observations are quantified in Fig. 1, B and D). The addition of sclerostin to these cultures appeared to have no effect on alkaline phosphatase-positive nodules in these early stage osteoblasts, but did inhibit alizarin red-stained nodules (−70.3%). Wnt3a (50 ng/ml) acted as an anabolic agent by stimulating the number of both alkaline phosphatase-stained and alizarin red-stained nodules. More importantly, Wnt activity was able to rescue, in part, the adverse effects of Pb on these bone-forming cultures. To further verify this effect, we extracted and measured the amount of calcium in the mineralized nodules. We found that Pb dose-dependently inhibited mineral deposition and was mitigated by Wnt3a (data not shown). No apparent cytotoxicity was observed in osteoblasts at the Pb doses administered (data not shown). These results suggested that Pb impacts osteogenesis via Wnt signaling.

FIGURE 1.

Pb inhibits osteogenesis, which is partially restored by co-treatment with Wnt3a. Mouse calvarial osteoblasts were differentiated to form bone nodules and treated with 0 (control (Ctrl)), 0.5, 2.0, and 5.0 μm Pb and in the presence of 50 ng/ml Wnt3a. A and C, mineralization was assessed by alkaline phosphatase staining (A) on day 10 and alizarin red staining (C) on day 20. Scl, sclerostin. B and D, images are representative of one trial; quantification of alkaline phosphatase (B) and alizarin red (D) staining was performed with ImageJ. Data represent mean ± S.E. for three trials. *, p < 0.05 versus control, #, p < 0.05 versus 2.0 μm Pb.

Pb Blunts Wnt/β-Catenin Activation through an Elevation in Sclerostin

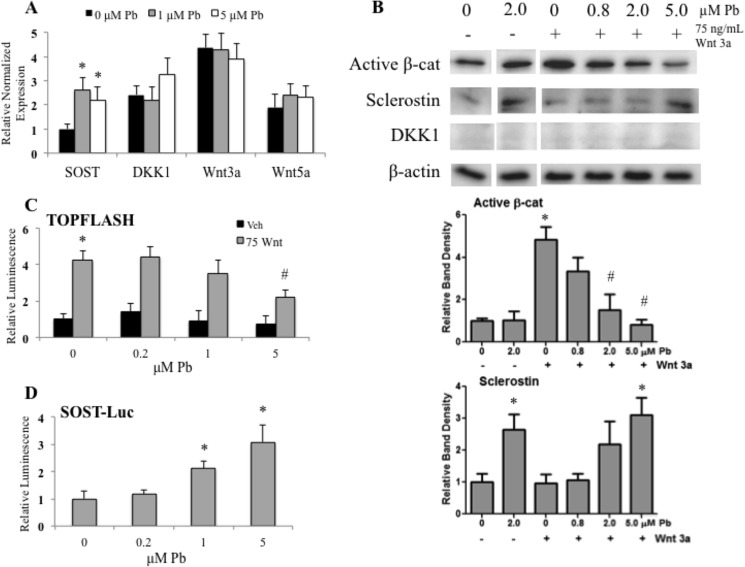

Further investigations were aimed at ascribing a mechanism to the effect of Pb on Wnt signaling. First, we assessed the gene expression of sclerostin, DKK1, Wnt3a, and Wnt5a. Primary osteoblasts were exposed to Pb, and mRNA expression was measured after 12 h, as this was found to be the most appropriate time to study the effects. Of the four secreted Wnt pathway regulators examined, only the amount of SOST RNA was significantly elevated following 2 and 5 μm Pb as compared with the untreated controls (Fig. 2A). Next, upon activating osteoblasts with 75 ng/ml Wnt3a for 12 h, we observed a significant 5.6-fold increase in activated β-catenin. However, in osteoblasts pretreated with Pb for 48 h prior to Wnt administration, Wnt-stimulated levels of activated β-catenin were dose-dependently decreased (up to −80% at the 5 μm Pb concentration) as compared with unexposed stimulated cells (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis further revealed that Pb induced the expression of sclerostin protein that routinely achieved 2–4-fold stimulation over control levels. No effect of Pb on the inhibitor DKK1 was observed.

FIGURE 2.

Pb inhibits Wnt signaling in osteoblasts. A, real-time PCR analysis on total RNA in calvarial osteoblasts following a 24-h exposure to increasing Pb. We examined the expression of two Wnt signaling antagonists (SOST and DKK1) and Wnt signaling agonists (Wnt3a and Wnt5a). Osteoblastic cells were treated with control or Pb-conditioned medium at the dose indicated and then stimulated with Wnt3a for 12 h. B, representative Western blots (above) of the active form of β-catenin (β-cat) and Wnt antagonists with quantification (below). C and D, data from luciferase (Luc) reporters of TOPFLASH (C) and 7-kb upstream SOST promoter activity (D) are shown when activated with Wnt3a and treated with Pb. Veh, vehicle. Data represent mean ± S.E. for three trials. *, p < 0.05 versus control, #, p < 0.05 versus activation + Pb.

In MC3T3 osteoblasts transfected with the TOPFLASH reporter, 75 ng/ml Wnt3a significantly induced luciferase activity by 4.2-fold (Fig. 2C); however, this induction was repressed with increasing Pb concentrations (48% inhibition at 5.0 μm). Fig. 2D shows that at 1.0 and 5.0 μm Pb exposure, osteoblasts transfected with a 7-kb intact promoter for SOST showed a significant increase in gene activity (i.e. 2.2- and 3.1-fold, respectively). Together these data indicated that Pb can repress the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and that one likely mechanism is through the up-regulation of SOST gene activity and sclerostin protein expression.

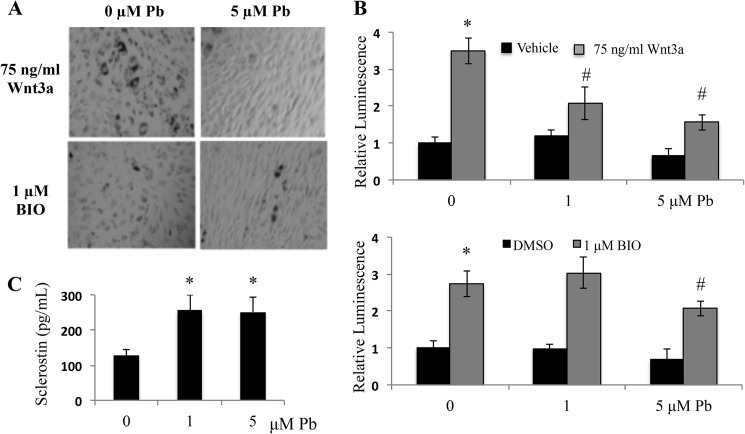

β-Catenin Signaling Is Inhibited by Pb in Osteogenic Bone Marrow Cells

Next, the effects of Pb on MSCs isolated from TOPGAL mice were evaluated. Pb depressed the staining frequency and intensity of cells from Wnt-stimulated cultures (Fig. 3A). However, when we stimulated the MSC cultures with BIO, the inhibitory effect of Pb was less pronounced. Fig. 3B supported the same trend while evaluating the effect of Pb on the TOPFLASH reporter. That is, Pb showed a statistically significant dose-dependent depression of reporter luminescence when the cells were stimulated with Wnt3a; however, Pb only inhibited the BIO effect at the highest Pb concentration tested. As a final confirmation of this effect, protein levels of sclerostin in the same cultures displayed in Fig. 3A were measured using an ELISA assay. We found at least a 2-fold increase in sclerostin protein after Pb treatment (Fig. 3C). These data support our supposition that Pb inhibits the β-catenin pathway at a point upstream of the site of action of BIO and were consistent with the major effect being the stimulation of sclerostin expression.

FIGURE 3.

Pb depresses Wnt3a stimulated β-catenin signaling in TOPGAL cells. Bone marrow from TOPGAL transgenic mice was isolated and stimulated with osteogenic medium. Subsequently, cell cultures were given treatment of either Wnt or BIO in combination with Pb. A, images are representative of X-gal-stained cell cultures from each treatment group: BIO and Wnt treatment with and without Pb. B, β-catenin signaling was measured following activation from either Wnt3a or BIO in the context of Pb using a luminescent substrate for β-galactosidase. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. C, sclerostin protein levels in medium following 72 h of Pb were measured with ELISA. Data represent mean ± S.E. for three trials. *, p < 0.05 versus control, #, p < 0.05 versus vehicle + Pb.

Characterization of the Effect of Pb in Mice Devoid of the SOST Gene

In these experiments, mice lacking the SOST gene were assessed to determine resistance to the deleterious effect of Pb on bone mass and osteoblast function (1). First, Pb levels were measured in bone specimens from the treated animals. A dose-dependent increase was established in bone Pb in both the WT and the SOST-KO animals (Table 1). Pb deposition was greater in SOST-KO mice exposed to 50 ppm as compared with wild-type mice exposed to 50 ppm of Pb. In addition, serum sclerostin levels were increased with elevated Pb exposure in wild-type mice at 200 ppm. Serum DKK1 levels were also up-regulated by Pb and unaltered in SOST-KO mice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Levels of bone Pb (ng Pb/mg of dry tibial bone) and serum Wnt antagonists sclerostin (pg/ml) and DKK1 (ng/ml) in male WT and SOST-KO mice at 3 months

Pb was determined in mineralized tissue by atomic absorption. Data represent mean ± S.E. for 5 mice/group.

| Bone Pb | 0 ppm of Pb | 50 ppm of Pb | 200 ppm of Pb |

| Wild type | 0.61 ± 0.18 | 29.11 ± 8.39a | 110.09 ± 4.05a |

| SOST-KO | 0.79 ± 0.26 | 81.70 ± 10.46b,c | 129.68 ± 13.85b |

| Sclerostin | |||

| Wild type | 367.8 ± 27.5 | 342.4 ± 22.8 | 553.8 ± 91.7a |

| SOST-KO | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DKK1 | |||

| Wild type | 6.98 ± 4.29 | 25.07 ± 12.25d | 35.88 ± 8.59a |

| SOST-KO | 5.73 ± 1.29 | 22.21 ± 20.62 | 31.63 ± 27.07e |

a p < 0.005 versus 0 Pb WT.

b p < 0.005 versus 0 Pb KO.

c p < 0.05 versus 50 Pb WT.

d p < 0.05 versus 0 Pb WT.

e p < 0.05 versus 0 Pb KO.

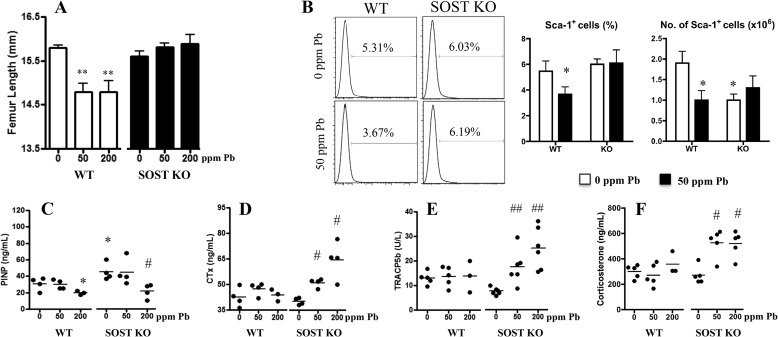

Next, anatomical measurements of femoral length in wild-type animals treated with Pb had significantly shorter long bones as compared with controls (Fig. 4A). Pb-exposed SOST-deficient mice showed no difference in femoral length. So although accumulation of Pb in SOST-KO bone tissue was greater than in WT mice, femur bone length was not compromised.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of increasing Pb on long bone length, bone turnover markers, and osteoblast precursors in sclerostin-deficient mice. A, gross measurements of total femur length were taken and are presented for each treatment group. B, MSC populations from Pb-treated 3-month-old WT and SOST-KO mice were isolated and sorted for their positive surface expression of Sca-1. The percentage and total number of Sca-1+ cells were quantified. C–F, serum bone formation marker P1NP (C), resorption markers CTX-1 (D) and TRAP5b (E), and corticosterone (F) were measured using standard ELISA methods. Data represent mean ± S.E. of 5 mice/group. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.005 versus 0 Pb WT, #, p < 0.05, ##, p < 0.005 versus 0 Pb KO.

To determine whether Pb affected osteoblast precursors, the number of Sca-1-expressing MSCs from bone marrow was quantified, and serum biomarkers and hormone regulators of bone formation and bone resorption were measured. The percentage of Sca-1+ osteoblastic precursors in the bone marrow of wild-type animals was decreased by exposure to 50 ppm of Pb, whereas no change in stem cell percentage in the SOST null animals was observed under the influence of Pb (Fig. 4B). As expected, the bone formation marker P1NP was significantly increased in SOST-KO mice (Fig. 4C). Also Pb treatment was able to depress this maker in both wild-type and SOST-deficient animals. With regard to the effect of Pb on bone resorption, elevated levels of CTX and TRAP were observed only in the knock-out animals (Fig. 4, D and E). Along with this, corticosterone, the dominant glucocorticoid expressed in rodents, was elevated with Pb exposure in the KO mouse (Fig. 4F). These data indicate a complex interrelationship between the effects of Pb and the β-catenin pathway and implicate multifaceted regulatory pathways in the control of bone resorption by Pb and sclerostin.

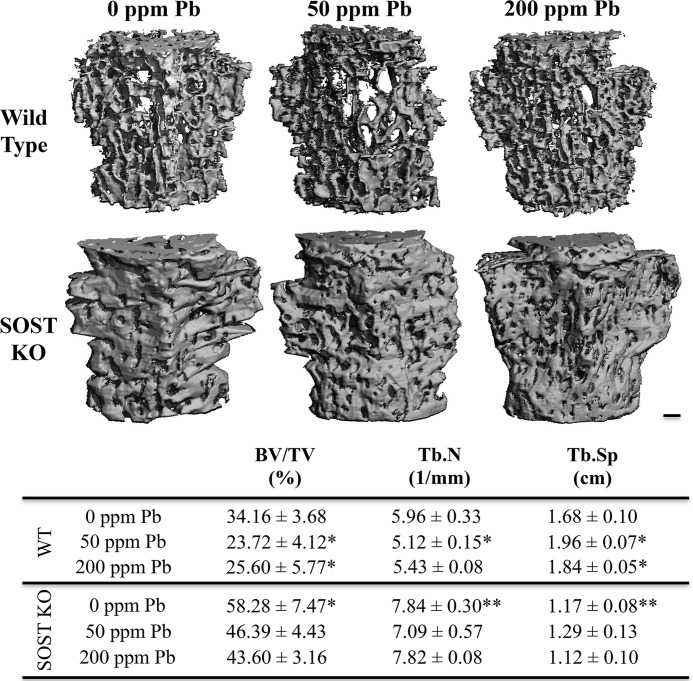

SOST-KO Mice Are Resistant to Pb-induced Decreases in Vertebral Bone Mass and Strength

Quantitative analysis by microCT of trabecular bone in mouse vertebrae showed that SOST-KO mice had significantly increased bone volume per total volume (BV/TV) (+1.7-fold) and trabecular number (Tb.N) (+1.3-fold) and significantly decreased trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp) (−31.4%) as compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 5). Following 6 months of 50 ppm of Pb exposure in wild-type mice, there was a significant decrease in BV/TV (−29.4%) and Tb.N (−16.7%) as compared with WT controls. Simultaneously, we observed an increase in Tb.Sp (+1.12-fold) that correlated with the adverse changes in bone quality by low-level Pb in wild-type mice. In contrast, Pb exposure in the SOST-KO mice had no significant changes in bone parameters, suggesting that deletion of sclerostin rescued, in part, these deficits in bone quality.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of Pb exposure on bone volume and quality in vertebrae of SOST knock-out mice. Top, images are representative transverse sections from each control and Pb-exposed group in WT and SOST-KO mice. Bar: 200 μm. Bottom, trabecular bone was analyzed in the fourth lumbar vertebra in 6-month-old mice for the following bone parameters: BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp. Pb decreased bone mass and bone properties in WT mice. Bone in KO mice was unaffected by Pb. Data represent mean ± S.E. of 5 mice/group. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.005 versus 0 Pb WT.

To assess whether these adverse changes by Pb could have contributed to altered bone strength, destructive compression testing of isolated vertebrae was performed. Significant decreases in material bone strength were observed with Pb treatment in wild-type animals, with reductions in maximum stiffness (−15.3% at 50 ppm of Pb, −14.6% at 200 ppm of Pb) and maximum load (−27.7% at 50 ppm of Pb, −14.5% at 200 ppm of Pb) as compared with controls (Table 2). Tensile properties were weaker in mice exposed to 50 ppm of Pb as demonstrated by a significant decrease in energy to failure (−41.0%) and post-yield energy (−50.8%). SOST-KO mice had superior bone mineral strength as compared with wild-type mice. Interestingly, KO mice treated with Pb had no measurable deficit in bone strength as compared with KO mice not exposed to Pb.

TABLE 2.

Biomechanical testing of lumbar vertebrae 4 in Pb-treated male WT and SOST-KO mice at 6 months old

Compression testing was applied to mouse vertebral bodies and resistance to force was calculated. Data represents mean ± S.E. for 5 mice/group. N, newtons.

| Maximum stiffness | Maximum force | Energy to failure | Post-yield energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N × mm | N | mJ | mJ | |

| Wild type | ||||

| 0 ppm of Pb | 105.5 ± 4.83 | 26.24 ± 1.49 | 5.05 ± 0.53 | 3.07 ± 0.32 |

| 50 ppm of Pb | 89.3 ± 4.11a | 18.95 ± 0.91b | 2.98 ± 0.31a | 1.51 ± 0.26b |

| 200 ppm of Pb | 90.1 ± 4.83a | 22.44 ± 0.48a | 4.41 ± 0.33 | 2.56 ± 0.36 |

| SOST-KO | ||||

| 0 ppm of Pb | 161.7 ± 2.97b | 33.96 ± 0.18b | 6.74 ± 0.38a | 3.59 ± 0.31 |

| 50 ppm of Pb | 166.4 ± 5.56 | 34.25 ± 0.51 | 7.47 ± 0.62 | 4.60 ± 0.61 |

| 200 ppm of Pb | 170.5 ± 3.41 | 34.57 ± 0.43 | 8.65 ± 0.69c | 5.76 ± 0.79c |

a p < 0.05 versus 0 Pb WT.

b p < 0.005 versus 0 Pb WT.

c p < 0.05 versus 0 Pb KO.

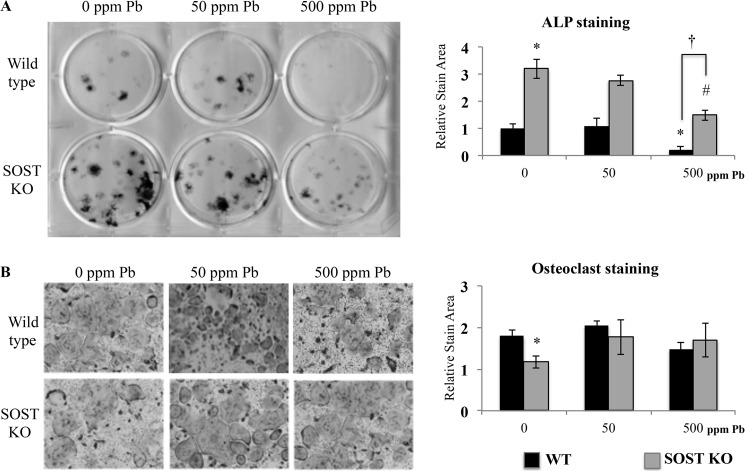

Bone Marrow from SOST-deficient Mice Is Protective against Pb Inhibition of MSC Function

Next, we determined the activity of progenitor cells harvested from 3-month-old WT and SOST-KO animals treated with Pb. Osteogenic activity was measured by alkaline phosphatase staining, and we found that the SOST-KO mice had a significant 3.2-fold increase in staining area (Fig. 6A) under control conditions. Cells from mice treated with 500 ppm of Pb in both WT and SOST-KO animals showed reduced alkaline phosphatase staining (−78.8% in WT, −45.3% in KO as compared with respective 0 ppm of Pb controls); however, the relative decrease of staining in MSCs from WT mice was significantly greater than in cells devoid of sclerostin. Subsequently, we induced isolated marrow cells to form osteoclasts. The osteoclastogenic potential of marrow cells harvested from KO mice was significantly less (−34.9%) when compared with WT mice (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, bone marrow cells from increasing Pb exposure (either 50 ppm of Pb or 500 ppm of Pb) in the KO mice showed no change in osteoclast formation. This indicated that the rise in osteoclast parameters that we observed previously in serum might be attributed to indirect effects of Pb independent of osteoclast formation potential.

FIGURE 6.

Pb inhibits osteogenesis and is rescued, in part, in cells from SOST knock-out mice. Bone marrow was harvested from 3-month-old WT and SOST-KO mice treated with 0, 50, or 500 ppm of Pb in drinking water. A, mesenchymal cells were induced by osteogenic medium to form bone nodules. Left, representative alkaline phosphatase staining on day 14 of differentiation. Right, quantification. B, osteoclastogenesis was initiated in marrow cells for 7 days. Left, representative osteoclasts are presented; right, TRAP-positive stains were quantified. Data represent mean ± S.E. for three trials. *, p < 0.05 versus WT control, #, p < 0.05 versus KO control.

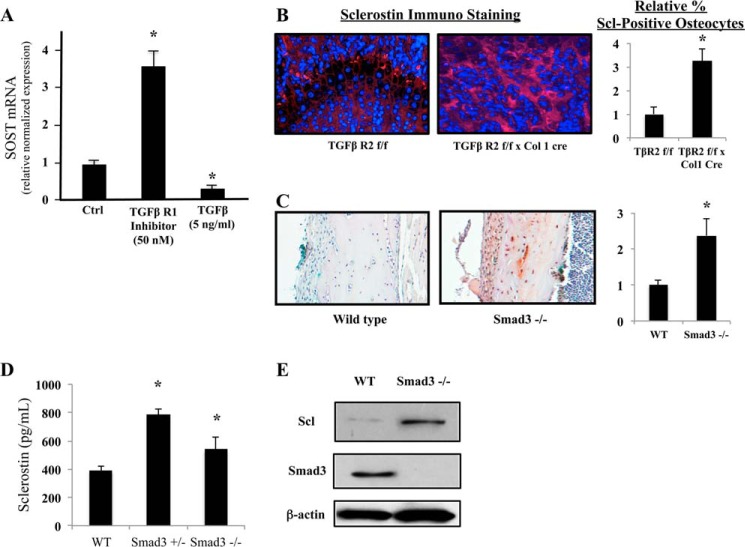

Potential Role of TGFβ Pathway in Mediating Effects of Pb on Sclerostin

Pb may exert its effect on the stimulation of sclerostin production by relieving an inhibition of SOST gene activity through the TGFβ/Smad3 signaling axis. The literature indicates that there exist methylated Smad-responsive elements in the SOST promoter (24, 25). Our data presented in Fig. 7 reveal that i) an inhibitor of TGFβ-mediated Smad3 phosphorylation strongly up-regulates sclerostin mRNA expression (Fig. 7A), ii) treatment of osteoblasts with TGFβ itself represses sclerostin mRNA expression (Fig. 7A), iii) osteoblast-specific deficiency in TGFβ signaling produces a 3.2-fold increase of sclerostin in bone cells around the epiphysis (Fig. 7B), and iv) mice that are devoid of Smad3 also produce a 2.4-fold elevation in sclerostin protein (Fig. 7C). ELISA analysis indicates that there is a significant systemic increase in sclerostin levels in both Smad3 heterozygous (Smad3+/−) and Smad3-KO mice as compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 7D). Subsequently, Western blot analyses from bone marrow cells of Smad3-KO animals confirm the immunohistochemical findings of elevated sclerostin (Fig. 7E). These data imply that canonical TGFβ signaling can repress sclerostin production in osteoblasts. There is evidence in the literature for both an inhibition (26) and a stimulation (27) of sclerostin expression by TGFβ. Although our data support the former, the issue is not yet resolved.

FIGURE 7.

The TGFβ/Smad3 signaling axis regulates sclerostin expression. A, mature primary osteoblasts express sclerostin mRNA in vitro. A TGFβ receptor inhibitor, TβRI-V#616456, strongly up-regulates transcription, whereas TGFβ itself significantly inhibits sclerostin mRNA production. Ctrl, control. B, immunofluorescent analysis at the femoral epiphysis demonstrates that in the absence of osteoblastic TGFβ receptor 2, there is more intense staining for sclerostin protein in the cells surrounding the growth plate. (left, representative images; right, quantification right). C, the number and intensity of sclerostin expression in osteocytes are elevated in mice that are devoid of Smad3 (left, representative images; right, quantification right). D, similarly, serum levels of sclerostin in 3-month-old Smad3+/− and Smad3−/− mice were increased. E, representative Western blot analysis of bone marrow cells isolated from the animals shown in panel C for sclerostin (Scl) and Smad3 expression. Data represent mean ± S.E. for three trials. *, p < 0.05 versus control.

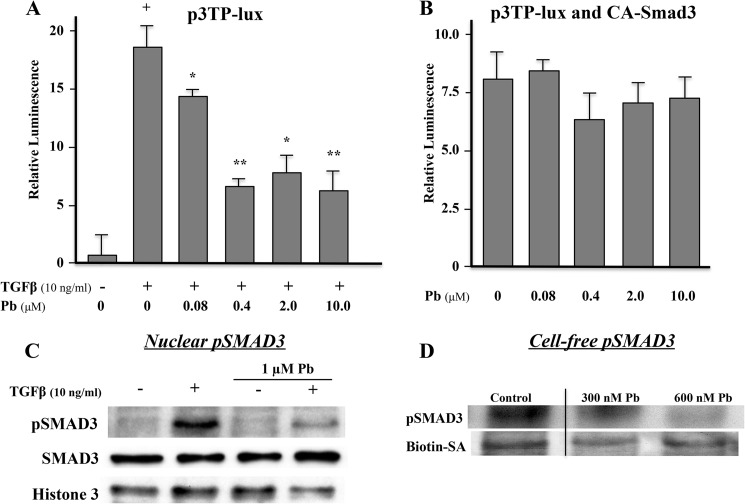

Pb depresses Smad3 reporter activity apparently through a direct effect on the type 1 TGFβ receptor. In osteoblasts, TGFβ stimulated a 15–20-fold increase in p3TP-lux activity (Fig. 8A). Pb dose-dependently inhibited TGFβ induced activity, reaching 65% at a concentration of 0.4 μm (Fig. 8A). However, when osteoblasts were co-transfected with a constitutively active construct of Smad3, the inhibitory effect Pb on TGFβ signaling was lost (Fig. 8B). Moreover, treatment of osteoblasts with Pb after 30 min of TGFβ stimulation leads to a marked diminution of phospho-Smad3 in nuclei without affecting the total level of Smad3 protein (Fig. 8C). To determine whether this was a direct effect of Pb on the TGFβ type 1 receptor kinase, we performed a series of cell-free experiments. Using a Pb-sensitive dye (Indo-1, Life Technologies), whose fluorescence is strongly quenched over the range of 10–2,500 nm (28), we determined that Pb in the culture medium between 1.0 and 10 μm induced a cytosolic concentration of 300–600 nm in the cells (data not shown). We then used these concentrations to measure the effects of Pb on cell-free extracts of calvaria osteoblast membranes using a magnetic bead pulldown assay to detect phosphorylation of Smad3. Fig. 8D shows that even in a cell-free system, Pb is able to inhibit phosphorylation of Smad3 at concentrations that would be found inside of cells. Thus, the data in Figs. 7 and 8 are consistent with a mechanism whereby Pb can induce sclerostin expression in bone cells through a process involving inhibition of TGFβ-induced Smad3 phosphorylation.

FIGURE 8.

Pb blocks TGFβ signaling by inhibiting Smad3 phosphorylation. A, following TGFβ induction, increasing concentrations of Pb significantly diminished Smad3 reporter activity in osteoblastic cell cultures. B, a constitutively active Smad3 rescues p3TP-lux reporter activity in Pb-treated cells. Data represent mean ± S.E. for five trials; *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.005 versus TGFβ alone, +, p < 0.005 versus control. C, Western blot analysis demonstrates that TGFβ can increase the level of phospho-Smad3 (pSMAD3 in the nucleus and that Pb can inhibit this effect. The total amount of nuclear Smad3 was unaffected. D, Pb inhibits phosphorylation of Smad3 in a cell-free system at 300–600 nm. Biotin-SA was used as a loading control in these experiments.

Discussion

There is growing awareness of the pleiotropic effects of Pb, with targets of toxicity including the skeleton. In fact, at concentrations considered below the level of safety concern, it is known that Pb affects skeletal growth, as demonstrated by decreases in stature (29), axial growth (30), and bone accrual (31) during childhood. The findings presented in this study demonstrated that Pb inhibited osteoblastic activity and depressed the critical Wnt signaling pathway in bone. Specifically, both calvarial osteoblasts and bone marrow cells exposed to Pb displayed a severalfold depression in osteogenic bone nodule formation and calcification. This represented a first step toward understanding the mechanism underlying the influence of Pb on bone formation. To our knowledge, this is the first characterization of the effect of Pb on Wnt/β-catenin signaling and identifies a robust alteration in signaling activity on this fundamental biological pathway.

In the present study, Pb inhibited Wnt signaling. Pb exposure achieved this by competing with Wnt3a to block its stimulatory effect on active β-catenin activity. Moreover, our data suggest that sclerostin may mediate these effects, which is supported by Pb induction of the 7-kb SOST luciferase reporter, SOST mRNA, and sclerostin protein levels. Furthermore, Pb depression of Wnt signaling was minimal when activating β-catenin downstream of the surface receptors with the small molecule BIO. This finding further elucidated the site of action of Pb inhibition on the Wnt pathway and validated sclerostin as a viable candidate.

The effects of Pb on mice devoid of the SOST gene were complex in nature. Many of the Pb-induced adverse changes on the normal mouse skeleton were mitigated in the absence of sclerostin. In particular, SOST-KO mice exposed to Pb displayed preservation of bone strength, size, trabecular vertebral bone quality, and osteoblast activity. The clinical biomarker P1NP was decreased, an indicator of reduced osteoblastic bone formation, and surprisingly, an increase in CTX-1 (an indicator of elevated osteoclastic bone resorption) with Pb in SOST-KO mice was observed. It appears that in the absence of sclerostin, we may have uncovered a stimulatory effect of Pb on markers of osteoclastic activity. There is speculation that sclerostin may act on osteoclasts, as discovered by short duration clinical trials with the sclerostin-neutralizing antibody that have found increases in P1NP but also decreases in CTX-1 (32). Thus, sclerostin may function to stimulate resorption via a yet unexplored mechanism. In sclerostin-deficient mice, Pb could be acting through the same mechanism. This may be attributed, in part, to the observed stimulation of corticosterone levels, which Pb exposure has previously been reported to elevate (33, 34). Furthermore, it is known that glucocorticoid therapy increases bone resorption (35) and has also been shown to elevate sclerostin levels (36), which may potentially link a systemic pathway involving the adrenal axis and Pb to disruption of bone homeostasis. The effect of Pb or sclerostin on osteoclast support cells is another potential target to produce changes in bone resorption (37). Further investigations of this observation are warranted.

With the intent of identifying which cell type contributes to the Pb-induced decrease in bone mass, the effect of the heavy metal was evaluated on the relative osteoblastic precursor populations and differentiation potential of MSCs in WT and SOST-KO mice. Elimination of SOST gene expression prevented the depletion of Sca-1+-expressing bone marrow cells caused by Pb exposure. The drop in total Sca-1+ MSCs in SOST-KO mice was not surprising given the bony overgrowth that occurs in animals devoid of sclerostin that narrows the marrow cavity (38). MSCs harvested from SOST-KO mice were less susceptible to Pb toxicity, showing improved osteoblastic activity. Osteoclastogenesis was not affected ex vivo; therefore, we believe that the increase in serum bone resorption markers found in Pb-treated SOST-KO was a systemic effect of Pb exposure.

The molecular mechanism to Pb induction of sclerostin gene expression may be complex as Pb has broad and multifaceted bioactivity on multiple intracellular signaling pathways. For instance, Pb has been shown in various tissues to i) block calcium signaling and inhibit Ca2+/phospholipid-dependent PKC signaling (39), ii) induce reactive oxygen species signaling (40), and iii) activate AP-1 signaling (41). We focused a series of experiments targeting the role of TGFβ in the regulation of sclerostin synthesis. Our data support the view that activation of the TGFβ pathway suppresses sclerostin production and inhibition of the pathway stimulates sclerostin production. Furthermore, Pb inhibited TGFβ reporter activity, blocked intracellular phosphorylation of Smad3, and prevented its translocation into the nucleus. Even in a cell-free membrane preparation, Pb was able to block phosphorylation of Smad3. Taken together these results support the notion that Pb blockade of TGFβ receptor kinase activity leads to a de-repression of SOST gene activity and a strong up-regulation of sclerostin protein production. There are precedents in the literature for our observations: i) Smad3 is known to function as a transcriptional repressor of specific genes (42, 43); ii) Pb blocks Smad3 phosphorylation and the TGFβ pathway (44); and iii) in the absence of TGFβ activity, mechanical loading induces a very strong up-regulation of sclerostin in cortical bone (26).

The studies presented here establish that in addition to affecting bone mass, Pb inhibited the activity of osteoblasts to form a mineralized bone matrix. Although Pb depressed Wnt signaling, and this occurred in part through elevation of the inhibitor sclerostin, the entirety by which Pb decreased bone mass is likely complex and involves modulation and integration of multiple signaling pathways and tissue systems. Increased understanding of the mechanisms through which Pb regulates MSC fate and osteoblast function and subsequently affects bone strength is critical, given the continued presence of Pb in both industrialized and developing nations.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Mack and K. Maltby for assistance with histology, R. Gelein for bone Pb measurements, and M. Thullen for microCT imaging and analysis. Biomechanical testing was performed with assistance from Drs. H. Awad and J. Inzana in the Biomechanics and Multimodal Tissue Imaging Core laboratory, established by National Institutes of Health Grant P30 AR061307.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Public Health Service Grants T32 ES07026, R01 ES012712, T32 AR053459, P01 ES011854, and P30 ES301247 (to J. E. P.). Six of the authors declare they have no competing financial interests. P. B. is an employee of Amgen, Inc. and has received stock and stock options from Amgen, Inc.

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell

- BIO

- 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime

- P1NP

- type 1 procollagen

- CTX

- C-terminal telopeptide

- microCT

- microcomputed tomography

- BV/TV

- bone volume per total volume

- Tb.N

- trabecular number

- Tb.Sp

- trabecular spacing

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

References

- 1. Beier E. E., Maher J. R., Sheu T. J., Cory-Slechta D. A., Berger A. J., Zuscik M. J., Puzas J. E. (2013) Heavy metal lead exposure, osteoporotic-like phenotype in an animal model, and depression of Wnt signaling. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 97–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gruber H. E., Gonick H. C., Khalil-Manesh F., Sanchez T. V., Motsinger S., Meyer M., Sharp C. F. (1997) Osteopenia induced by long-term, low- and high-level exposure of the adult rat to lead. Miner. Electrolyte Metab. 23, 65–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein R. F., Wiren K. M. (1993) Regulation of osteoblastic gene expression by lead. Endocrinology 132, 2531–2537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sauk J. J., Smith T., Silbergeld E. K., Fowler B. A., Somerman M. J. (1992) Lead inhibits secretion of osteonectin/SPARC without significantly altering collagen or Hsp47 production in osteoblast-like ROS 17/2.8 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 116, 240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Angle C. R., Thomas D. J., Swanson S. A. (1990) Lead inhibits the basal and stimulated responses of a rat osteoblast-like cell line ROS 17/2.8 to 1 α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IGF-I. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 103, 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Long G. J., Pounds J. G., Rosen J. F. (1992) Lead intoxication alters basal and parathyroid hormone-regulated cellular calcium homeostasis in rat osteosarcoma (ROS 17/2.8) cells. Calcif. Tissue Int. 50, 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buttery L. D., Bourne S., Xynos J. D., Wood H., Hughes F. J., Hughes S. P., Episkopou V., Polak J. M. (2001) Differentiation of osteoblasts and in vitro bone formation from murine embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. 7, 89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu H., Hilton M. J., Tu X., Yu K., Ornitz D. M., Long F. (2005) Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 132, 49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peifer M., Rauskolb C., Williams M., Riggleman B., Wieschaus E. (1991) The segment polarity gene armadillo interacts with the wingless signaling pathway in both embryonic and adult pattern formation. Development 111, 1029–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li X., Zhang Y., Kang H., Liu W., Liu P., Zhang J., Harris S. E., Wu D. (2005) Sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 and antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19883–19887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li X., Ominsky M. S., Warmington K. S., Morony S., Gong J., Cao J., Gao Y., Shalhoub V., Tipton B., Haldankar R., Chen Q., Winters A., Boone T., Geng Z., Niu Q. T., Ke H. Z., Kostenuik P. J., Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L., Paszty C. (2009) Sclerostin antibody treatment increases bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 578–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ominsky M. S., Vlasseros F., Jolette J., Smith S. Y., Stouch B., Doellgast G., Gong J., Gao Y., Cao J., Graham K., Tipton B., Cai J., Deshpande R., Zhou L., Hale M. D., Lightwood D. J., Henry A. J., Popplewell A. G., Moore A. R., Robinson M. K., Lacey D. L., Simonet W. S., Paszty C. (2010) Two doses of sclerostin antibody in cynomolgus monkeys increases bone formation, bone mineral density, and bone strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 948–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Declercq H., Van den Vreken N., De Maeyer E., Verbeeck R., Schacht E., De Ridder L., Cornelissen M. (2004) Isolation, proliferation and differentiation of osteoblastic cells to study cell/biomaterial interactions: comparison of different isolation techniques and source. Biomaterials 25, 757–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aronow M. A., Gerstenfeld L. C., Owen T. A., Tassinari M. S., Stein G. S., Lian J. B. (1990) Factors that promote progressive development of the osteoblast phenotype in cultured fetal rat calvaria cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 143, 213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu L., van der Valk M., Cao J., Han C. Y., Juan T., Bass M. B., Deshpande C., Damore M. A., Stanton R., Babij P. (2011) Sclerostin expression is induced by BMPs in human Saos-2 osteosarcoma cells but not via direct effects on the sclerostin gene promoter or ECR5 element. Bone 49, 1131–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chipuk J. E., Cornelius S. C., Pultz N. J., Jorgensen J. S., Bonham M. J., Kim S. J., Danielpour D. (2002) The androgen receptor represses transforming growth factor-β signaling through interaction with Smad3. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1240–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferguson C. M., Schwarz E. M., Reynolds P. R., Puzas J. E., Rosier R. N., O'Keefe R. J. (2000) Smad2 and 3 mediate transforming growth factor-β1-induced inhibition of chondrocyte maturation. Endocrinology 141, 4728–4735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fuhrmann S., Riesenberg A. N., Mathiesen A. M., Brown E. C., Vetter M. L., Brown N. L. (2009) Characterization of a transient TCF/LEF-responsive progenitor population in the embryonic mouse retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 432–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DasGupta R., Fuchs E. (1999) Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development 126, 4557–4568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li X., Ominsky M. S., Niu Q. T., Sun N., Daugherty B., D'Agostin D., Kurahara C., Gao Y., Cao J., Gong J., Asuncion F., Barrero M., Warmington K., Dwyer D., Stolina M., Morony S., Sarosi I., Kostenuik P. J., Lacey D. L., Simonet W. S., Ke H. Z., Paszty C. (2008) Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23, 860–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chytil A., Magnuson M. A., Wright C. V., Moses H. L. (2002) Conditional inactivation of the TGF-β type II receptor using Cre:Lox. Genesis 32, 73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang X., Letterio J. J., Lechleider R. J., Chen L., Hayman R., Gu H., Roberts A. B., Deng C. (1999) Targeted disruption of SMAD3 results in impaired mucosal immunity and diminished T cell responsiveness to TGF-β. EMBO J. 18, 1280–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamashita T., Yao Z., Li F., Zhang Q., Badell I. R., Schwarz E. M., Takeshita S., Wagner E. F., Noda M., Matsuo K., Xing L., Boyce B. F. (2007) NF-κB p50 and p52 regulate receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and tumor necrosis factor-induced osteoclast precursor differentiation by activating c-Fos and NFATc1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18245–18253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delgado-Calle J., Arozamena J., Pérez-López J., Bolado-Carrancio A., Sañudo C., Agudo G., de la Vega R., Alonso M. A., Rodríguez-Rey J. C., Riancho J. A. (2013) Role of BMPs in the regulation of sclerostin as revealed by an epigenetic modifier of human bone cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 369, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sutherland M. K., Geoghegan J. C., Yu C., Winkler D. G., Latham J. A. (2004) Unique regulation of SOST, the sclerosteosis gene, by BMPs and steroid hormones in human osteoblasts. Bone 35, 448–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nguyen J., Tang S. Y., Nguyen D., Alliston T. (2013) Load regulates bone formation and Sclerostin expression through a TGFβ-dependent mechanism. PLoS One 8, e53813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loots G. G., Keller H., Leupin O., Murugesh D., Collette N. M., Genetos D. C. (2012) TGF-β regulates sclerostin expression via the ECR5 enhancer. Bone 50, 663–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kerper L. E., Hinkle P. M. (1997) Cellular uptake of lead is activated by depletion of intracellular calcium stores. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8346–8352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ballew C., Khan L. K., Kaufmann R., Mokdad A., Miller D. T., Gunter E. W. (1999) Blood lead concentration and children's anthropometric dimensions in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988–1994. J. Pediatr. 134, 623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ignasiak Z., Sławińska T., Rozek K., Little B. B., Malina R. M. (2006) Lead and growth status of school children living in the copper basin of south-western Poland: differential effects on bone growth. Ann. Hum. Biol. 33, 401–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kafourou A., Touloumi G., Makropoulos V., Loutradi A., Papanagiotou A., Hatzakis A. (1997) Effects of lead on the somatic growth of children. Arch. Environ. Health 52, 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Padhi D., Jang G., Stouch B., Fang L., Posvar E. (2011) Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haider S., Saleem S., Tabassum S., Khaliq S., Shamim S., Batool Z., Parveen T., Inam Q. U., Haleem D. J. (2013) Alteration in plasma corticosterone levels following long term oral administration of lead produces depression like symptoms in rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 28, 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cory-Slechta D. A., Stern S., Weston D., Allen J. L., Liu S. (2010) Enhanced learning deficits in female rats following lifetime Pb exposure combined with prenatal stress. Toxicol. Sci. 117, 427–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canalis E., Delany A. M. (2002) Mechanisms of glucocorticoid action in bone. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 966, 73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gifre L., Ruiz-Gaspà S., Monegal A., Nomdedeu B., Filella X., Guañabens N., Peris P. (2013) Effect of glucocorticoid treatment on Wnt signalling antagonists (sclerostin and Dkk-1) and their relationship with bone turnover. Bone 57, 272–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wijenayaka A. R., Kogawa M., Lim H. P., Bonewald L. F., Findlay D. M., Atkins G. J. (2011) Sclerostin stimulates osteocyte support of osteoclast activity by a RANKL-dependent pathway. PLoS One 6, e25900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cain C. J., Rueda R., McLelland B., Collette N. M., Loots G. G., Manilay J. O. (2012) Absence of sclerostin adversely affects B-cell survival. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1451–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vázquez A., Peña de Ortiz S. (2004) Lead (Pb2+) impairs long-term memory and blocks learning-induced increases in hippocampal protein kinase C activity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 200, 27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang L., Wang Z., Liu J. (2010) Protective effect of N-acetylcysteine on experimental chronic lead nephrotoxicity in immature female rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 29, 581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hossain M. A., Bouton C. M., Pevsner J., Laterra J. (2000) Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor in human astrocytes by lead. Involvement of a protein kinase C/activator protein-1 complex-dependent and hypoxia-inducible factor 1-independent signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27874–27882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uchiyama Y., Guttapalli A., Gajghate S., Mochida J., Shapiro I. M., Risbud M. V. (2008) SMAD3 functions as a transcriptional repressor of acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) in nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23, 1619–1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li H., Xu D., Toh B. H., Liu J. P. (2006) TGF-β and cancer: is Smad3 a repressor of hTERT gene? Cell Res. 16, 169–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Holz J. D., Beier E., Sheu T. J., Ubayawardena R., Wang M., Sampson E. R., Rosier R. N., Zuscik M., Puzas J. E. (2012) Lead induces an osteoarthritis-like phenotype in articular chondrocytes through disruption of TGF-β signaling. J. Orthop. Res. 30, 1760–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]