Abstract

Cysteine metabolism is considered essential for the crucial maintenance of a reducing environment in trypanosomatids due to its importance as a precursor of trypanothione biosynthesis. Expression, activity, functional rescue, and overexpression of cysteine synthase (CS) and cystathionine β-synthase (CβS) were evaluated in Leishmania braziliensis promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes under in vitro stress conditions induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, or antimonial compounds. Our results demonstrate a stage-specific increase in the levels of protein expression and activity of L. braziliensis CS (LbrCS) and L. braziliensis CβS (LbrCβS), resulting in an increment of total thiol levels in response to both oxidative and nitrosative stress. The rescue of the CS activity in Trypanosoma rangeli, a trypanosome that does not perform cysteine biosynthesis de novo, resulted in increased rates of survival of epimastigotes expressing the LbrCS under stress conditions compared to those of wild-type parasites. We also found that the ability of L. braziliensis promastigotes and amastigotes overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS to resist oxidative stress was significantly enhanced compared to that of nontransfected cells, resulting in a phenotype far more resistant to treatment with the pentavalent form of Sb in vitro. In conclusion, the upregulation of protein expression and increment of the levels of LbrCS and LbrCβS activity alter parasite resistance to antimonials and may influence the efficacy of antimony treatment of New World leishmaniasis.

INTRODUCTION

The intracellular protozoan parasite Leishmania causes a neglected infectious disease commonly referred to as leishmaniasis. Depending on the infecting species and the immune status of the host, leishmaniasis can result in a variety of clinical manifestations with cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral involvement (1–3). Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis, the causative agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, is the most prevalent species infecting humans in the Americas (4, 5).

Leishmania spp. have a digenetic life cycle, alternating between flagellated promastigote forms in the midgut of the sand fly and obligatory intracellular amastigotes within macrophages of the mammalian host (6, 7). During this complex life cycle, these parasites are exposed to variable oxidative or nitrosative stresses induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS), respectively, generated by the host immune system to avoid infection (8, 9). Antimonial compounds, such as sodium stibogluconate or Sb (Pentostan) or meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime), are still the first-choice drugs for human leishmaniasis treatment (10). Among these, the Sb pentavalent form (SbV) has been reported to indirectly induce oxidative and nitrosative stress on the parasite by stimulating infected macrophages (Mϕ) to generate ROS and nitric oxide (NO) via activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase C (PKC), and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (11). Additionally, the reduced form of the drug (potassium antimonyl tartrate trihydrate [SbIII]) binds to the parasite thiols, which inhibits the action of trypanothione [T(SH)2] and leads to oxidative/nitrosative stress, perturbing the parasite redox balance and resulting in death (12, 13).

Since parasites are naturally exposed to a variety of oxidative (ROS) and/or nitrosative (RNS) stresses during their life cycles, they have developed an elaborate antioxidant defense system composed of molecules and enzymes to scavenge these reactive species (14, 15). These systems are primarily based on low-molecular-mass thiols, such as glutathione and trypanothione, which play central roles in the antioxidant defense mechanisms by regulating the redox homeostasis in parasites (16). The synthesis of glutathione and, thus, trypanothione depends on the availability of cysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid implicated in several biological processes of protein stability, structure, regulation of catalytic activity, and posttranslational modifications (17, 18).

Two different routes for cysteine biosynthesis have been described: the de novo or assimilatory and reverse transsulfuration (RTS) pathways. RTS has been demonstrated in fungi and mammals and includes the complete process leading to cysteine from methionine via the intermediary formation of cystathionine (19). These reactions are catalyzed by two enzymes, cystathionine β-synthase (CβS), which synthesizes cystathionine from homocysteine and serine, and cystathionine γ-lyase (CGL), which forms cysteine from cystathionine (20). The de novo pathway is also a two-step catalytic reaction starting with serine acetyltransferase (SAT) to form O-acetylserine (OAS) from l-serine and acetyl coenzyme A. Subsequently, OAS reacts with sulfide to produce cysteine in an alanyl transfer reaction mediated by cysteine synthase (CS) (21). This de novo pathway for cysteine biosynthesis is found in plants, bacteria, and some protozoan parasites, such as Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, Leishmania major, and Leishmania donovani, but is absent in mammals (22–25).

Considering the putative importance of thiol metabolism in Leishmania parasites so that they may respond to oxidative/nitrosative stress during their digenetic life cycle and the pivotal role of l-cysteine forms on the synthesis of thiol-related antioxidant molecules, in the present study we characterized genes encoding key enzymes of the cysteine biosynthesis pathway (CS and CβS) to determine whether these enzymes are involved in the antioxidant defense system in response to H2O2, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), or Sb compounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

Promastigotes of L. (Viannia) braziliensis (MHOM/BR/75/M2904) were grown at 26°C in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (26). Intracellular amastigotes were obtained by in vitro infection of THP-1 differentiated macrophages as described below. Epimastigotes of Trypanosoma rangeli (Choachí strain) were cultured in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium using formerly described conditions (27). Parasites were harvested at the exponential and late log phases of growth for DNA or protein extraction as well as for thiol profiling and in vitro oxidative and nitrosative stress testing.

Human THP-1-derived macrophages.

Cells of the human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 (ATCC) were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere using RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (28, 29). Monocytes were harvested during the logarithmic stage of growth and transferred to medium containing 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma) as an inductor of adherence and differentiation into macrophages. For assay of in vitro infection by L. braziliensis, a total of 1 × 105 cells were transferred to a 6-well plate and incubated for 72 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (30).

Macrophage infections.

Parasites from stationary growth phase were harvested after 6 days of passage and opsonized by treatment with RPMI 1640 containing 10% human type AB-positive serum for 1 h as described elsewhere (30). Infection of the macrophages was performed for 2 h at 34°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere using a parasite-to-cell ratio of 20:1, following removal of nonadherent parasites by washing the plate well twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After 24 h of incubation under the same conditions, L. braziliensis amastigotes were obtained by repeated passage of the infected macrophages through a 27-gauge needle, and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The L. braziliensis amastigotes were then obtained by centrifugation of the supernatant at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, washed twice in sterile PBS (pH 7.2), and submitted to total protein extraction.

Identification of LbrCS and LbrCβS.

A search for sequences coding for L. braziliensis MHOM/BR/75/M2904 cysteine synthase (LbrCS) and cystathionine β-synthase (LbrCβS) was carried out at the integrated database TriTrypDB (v.6.0; http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb). On the basis of the putative CS and CβS sequences retrieved from the L. braziliensis genome, the entire open reading frame (ORF) of the CS gene (1,002 bp) and a partial sequence of the CβS gene (360 bp) were PCR amplified from genomic DNA (gDNA) isolated by standard phenol-chloroform protocols (31). The primers used to amplify the CS and CβS genes contained appropriate restriction sites to ease downstream cloning (data not shown). All PCR assays were carried in a Mastercycler gradient (Eppendorf, Hamburg) using 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 1 min), annealing (45/62°C, 45 s), and extension (72°C, 30 s), followed by a final extension step (72°C) for 5 min. The PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the resulting constructs were verified by sequencing using a Megabace 1000 DNA analysis system with a DYEnamic ET Terminator kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's conditions. Both DNA strands of each clone obtained were sequenced, and only high-quality DNA sequences (Phred scores, ≥20), as defined by the Phred/Phrap/Consed package (32), were compared to the sequences in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/) using the BLAST algorithm.

Protein expression and purification.

The CS ORF was subcloned into a pET21a expression vector (Novagen) that had been predigested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and resequenced as described above to ensure the maintenance of the reading frame. The resulting construct was named pET21-LbrCS and was used to transform Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) for recombinant protein expression. A preinoculum was grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C and then used to inoculate fresh LB broth until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 was reached. The expression of recombinant L. braziliensis CS (rLbrCS) was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were harvested and resuspended in 5 ml of buffer A (50 mM sodium phosphate [NaH2PO4], 0.3 M NaCl, pH 8.0, 25 μM pyridoxal phosphate [PLP]) containing 5 mM imidazole and then disrupted by sonication. The soluble and insoluble fractions were recovered by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C (23). rLbrCS was purified from soluble fractions by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) on Talon metal affinity resin (Clontech) following standard procedures. Briefly, the soluble fraction was applied to Talon metal affinity resin (Clontech) that had been preequilibrated with a proper buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 0.3 M NaCl, pH 7.4) and then incubated for 20 min at 4°C under continuous agitation. The resin was washed three times using washing buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.4), and rLbrCS (35 kDa) elution was carried out using a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 0.3 M NaCl, and 150 mM imidazole (pH 7.4). The eluted proteins were dialyzed overnight at 4°C using 50 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, and 25 μM PLP, pH 8.0. After assessment of the purity of the recombinant protein by SDS-PAGE and concentration by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin as a standard, the rLbrCS protein was stored at −20°C until used. Recombinant T. rangeli CβS (rTrCβS) was obtained as formerly described (27).

Generation of anti-rLbrCS polyclonal antibodies.

The scheme used for immunization of BALB/c mice consisted of four consecutive subcutaneous inoculations of ∼50 μg of purified rLbrCS at 12-day intervals using Alu-Gel (Serva) as an adjuvant. The antibody response was monitored via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using rLbrCS as the antigen.

Ethics statement.

The Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUA), as part of the Brazilian National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA), approved all procedures involving animals (reference number 23080.025618/2009-81), which were carried out according to CONCEA resolution no. 12. Mice were kept under controlled conditions (21°C, 12-h day/12-h night cycle) in microisolators, and water and food were provided ad libitum.

Comparative analysis of CS and CβS expression.

Quantification of CS and CβS expression by L. braziliensis promastigotes and amastigotes and T. rangeli epimastigotes was performed using soluble protein fractions as formerly described (27). Briefly, Western blot assays were carried out using 30 μg of each protein extract and polyclonal immune mouse antisera raised against rLbrCS (1:500, vol/vol) and rTrCβS (1:250, vol/vol) in blotting buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) containing 2% (wt/vol) nonfat milk. Detection of positive reactions was carried out using anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:10,000) and an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:10,000) was used as a loading control. The blots were digitally analyzed using ImageJ (v.1.463r) software as previously described (27). In summary, the integrated densities of the bands for each protein of interest and its corresponding loading control were determined. The ratio of the band intensity of the protein of interest to the band intensity of the corresponding loading control was used as the relative protein expression level and allowed comparison of expression levels relative to those in other samples.

CS and CβS enzymatic assays.

The CS and CβS enzymatic activities in total protein extracts (1.5 μg/μl) from L. braziliensis (promastigotes and amastigotes) and T. rangeli (epimastigotes) were assayed by measuring cystathionine or cysteine production at 37°C as formerly described (27). Each enzymatic assay was performed in triplicate and included positive controls (rLbrCS or rTrCβS) and negative controls (no enzyme and no substrate).

Parasite susceptibility to oxidative and nitrosative stress in vitro.

Parasite susceptibility to different oxidative/nitrosative stresses was assessed using an alamarBlue assay as previously reported (27, 33). Briefly, 5 × 105 parasites were exposed to 30% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich), S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; Molecular Probes, Life Technologies), or potassium antimonyl tartrate trihydrate (SbIII; Sigma-Aldrich), prepared at different dilutions, for 48 h at 26°C. After treatment, parasite viability was evaluated via determination of the fluorescence emission at 600 nm. Data from treated and nontreated cultures were used to calculate the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) by sigmoidal regression analysis (with normalized response with variable slope) using GraphPad Prism (v.5.0) software. Untreated control parasites and reagent blanks were included in each technical replicate. To evaluate the effect of oxidative or nitrosative stress on CβS and CS expression and activity in L. braziliensis, 1 × 108 promastigotes were incubated in the presence of the IC50 doses of H2O2 (550 μM) and SNAP (195 μM) at 26°C. Aliquots of treated parasites were collected at 1-, 2-, and 4-h intervals and were used for protein expression and enzymatic assays.

Intracellular total thiol contents.

The total reduced thiol content of L. braziliensis promastigotes was determined by Ellman's method, using deproteinized parasite extracts, as described previously (27).

Overexpression of CS and CβS genes in L. braziliensis.

The CS and CβS genes from L. braziliensis were PCR amplified as described above. The amplicons were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vectors and then subcloned into pTEXeGFP shuttle vectors expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), using the EcoRI/EcoRV sites to create the pTEXCSeGFP and pTEXCβSeGFP constructs, respectively. All constructs were checked by determination of their restriction profiles and DNA sequencing and then transfected into L. braziliensis promastigotes by electroporation, as described below for T. rangeli. Selection of the transfectants was carried out by culture on Schneider's medium supplemented with increasing concentrations of G418 (10 up to 60 μg ml−1). Stable transfectants were harvested at the exponential and late log phases for protein extraction as well as in vitro oxidative and nitrosative susceptibility assays, as described above, using wild-type (WT) parasites and mock-transfected parasites (parasites transfected with a plasmid with no insert) as controls.

Functional rescue of CS activity and heterologous expression of CβS in T. rangeli.

The pTEXCSeGFP construct (containing the L. braziliensis CS gene) and the pTEXCβSeGFP construct (carrying a partial sequence of the L. braziliensis CβS gene) were transfected into T. rangeli epimastigotes by electroporation using an Amaxa Nucleofector system (Lonza). Briefly, 5 × 107 epimastigotes in the logarithmic phase of growth were suspended in human T cell Nucleofector buffer (Lonza) and transfected with 10 μg DNA of the construct using the program U-033. After transfection, parasites were transferred to 1 ml of LIT medium and grown at 26°C for 24 h. Selection of stable transfectants was performed by incremental exposure to Geneticin (G418), starting with 20 μg ml−1 and going up to a final concentration of 400 μg ml−1.

Susceptibility of intracellular amastigotes to pentavalent antimony.

Susceptibility assays were performed in 8-well chamber slides (Nunc) using infection of in vitro-differentiated human THP-1 macrophages (8 × 105 cells/well) with L. braziliensis parasites transfected with the pTEXCSeGFP or pTEXCβSeGFP construct in a parasite-to-cell ratio of 10:1. Cultures were then treated with SbV antimony (Glucantime) at doses ranging from 8 to 256 μg ml−1 for 72 h at 34°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and a single change of drug-containing medium was done after 48 h. The cells were then washed twice in PBS, fixed with methanol, and stained with Giemsa. Experiments were carried out in biological duplicate, and drug-free controls were included in all assays. The percentage of infected cells and the number of intracellular amastigotes per cell (parasite burden) were determined by random counting of 300 cells per well under a ×100 magnification objective (Olympus IX70). Susceptibility was expressed as percent viability, determined by comparing the parasite burden of infected cells exposed to SbV to that of nontreated infected cells. The IC50 was estimated from both independent experiments by a sigmoidal regression analysis (with normalized response with variable slope) using GraphPad Prism (v.5.0) software.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate, and the results are presented as the mean and the standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM). Normalized data were analyzed by a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni posttests, as indicated in the figure legends, and correlation analyses using GraphPad Prism (v.5.0) software.

RESULTS

The L. braziliensis genome has genes encoding CS and CβS.

Comparative sequence analysis using the L. braziliensis MHOM/BR/75/M2904 genome allowed identification of single-copy genes encoding CS (LbrM.35.3820) and CβS (LbrM.17.0230), and the latter was found as a partial gene sequence. After cloning and sequencing, in silico analysis revealed that the L. braziliensis CS (LbrCS) gene encodes a protein of 333 amino acids (∼35.4 kDa) exhibiting, as expected, higher identity values with CS enzymes from other trypanosomatids, such as L. major, Leishmania infantum, L. donovani (90 to 91%), and Trypanosoma cruzi (75%). Comparison with other orthologous CS enzymes from other protozoan species, such as Trichomonas vaginalis and E. histolytica, as well as from plants and bacteria, revealed reduced but still interesting identity levels (∼50 to 55%). Analysis of the predicted amino acid sequences confirmed that LbrCS contains the four canonical lysine residues (Lys40, Lys51, Lys67, Lys199) that are crucial for the catalytic activity of the enzyme and that the consensus sequence for the putative cofactor pyridoxal phosphate-binding domain (PXXSVKDR) is conserved. LbrCS also contains the positively charged residues (Lys222-His226-Lys227) that are involved with binding to serine acetyltransferase (SAT) and the important β8-β9 short loop that is required for accessing the active site of the enzyme (data not shown).

The partial L. braziliensis CβS (LbrCβS) gene sequence predicts a 120-amino-acid protein (∼12.7 kDa) that revealed higher sequence identities with CβS enzymes from L. infantum, L. donovani, L. major (89%), T. rangeli (71%), T. cruzi (70%), and Trypanosoma brucei (69%) than the human CβS sequence (54%). Multiple-sequence alignment confirmed that LbrCβS contains two of the four lysine residues (Lys42, Lys53) required for CS activity, and the consensus sequence for the putative cofactor pyridoxal phosphate-binding domain is highly conserved. Like CβSs from other trypanosomatids, the LbrCβS differs from the Homo sapiens CβS (HsCβS) by lacking the heme-binding (redox sensor) and oxidoreductase (Cys-X-X-Cys) motifs at the N and C termini, respectively (data not shown).

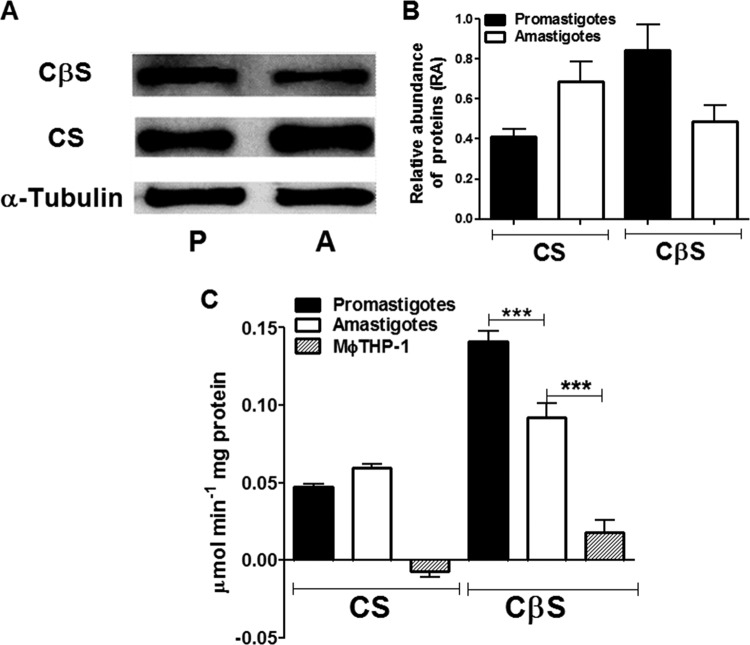

Stage-specific modulation of CS and CβS in L. braziliensis.

To examine whether protein expression and the activities of CS and CβS are stage specific, the relative abundance and specific activity of these proteins in soluble protein extracts from promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes of L. braziliensis were evaluated. Both the protein expression and the activity of CS were 1.3 to 1.7 times higher in the lysates of intracellular amastigotes than in those of promastigotes. In contrast, the protein expression and activity of CβS were shown to be more abundant (1.5 to 1.7 times) in the extracts from promastigotes than in those from amastigotes (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Detection of CS and CβS expression and activity levels in protein extracts of Leishmania braziliensis. (A) Western blot analysis of total extracts from promastigotes and amastigotes derived from THP-1 human macrophages. The equivalence of protein loading was controlled by immunodetection of α-tubulin. P, promastigotes; A, amastigotes. (B) Densitometry analysis of CS and CβS expression using ImageJ software. (C) CS and CβS activities in soluble extracts of parasite were determined. The results represent the average from three independent experiments performed in triplicate ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (***, P < 0.001).

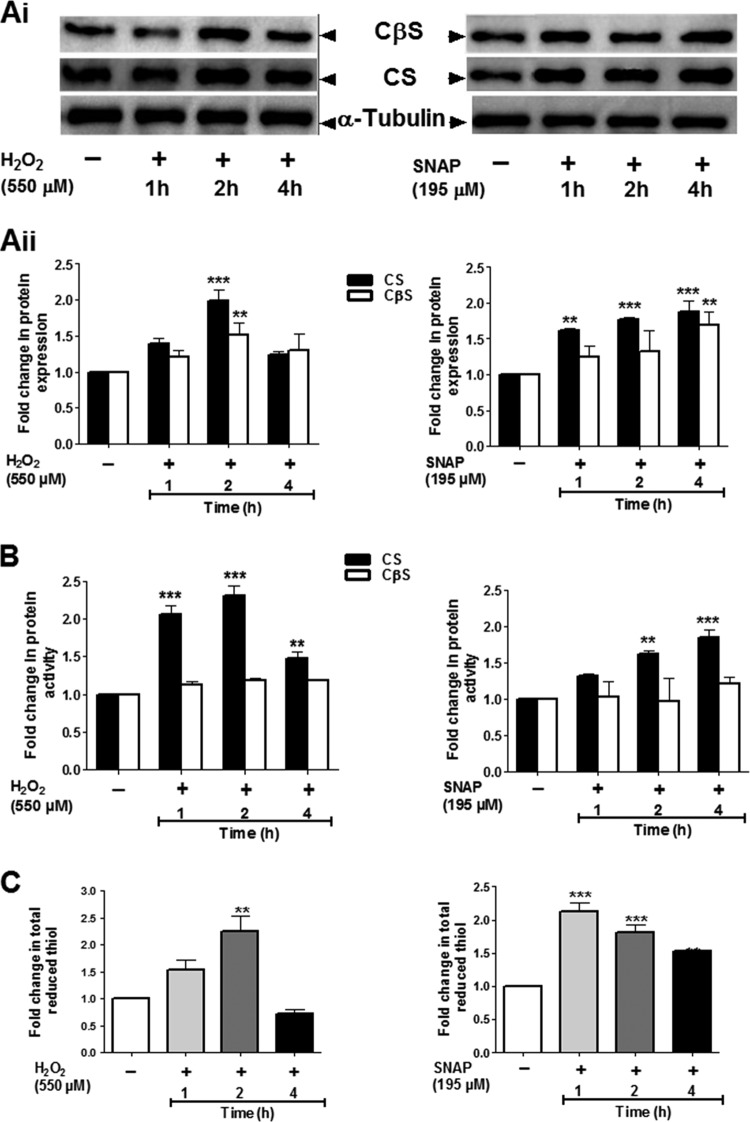

Addition of H2O2 and SNAP increased the protein expression levels and activity of CS and CβS in L. braziliensis promastigotes.

The protein expression level and specific activity of CS and CβS in soluble extracts from promastigotes of L. braziliensis exposed to H2O2 (550 μM) and SNAP (195 μM) were investigated. A time-dependent increase in protein expression and CS activity was observed in the extracts obtained from parasites exposed to both H2O2 and SNAP. Interestingly, significant increases in the protein expression level and specific activity of 2.0- to 2.3-fold were observed within the first 2 h, and at 4 h, the values were less than those observed at 1 h of exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, when parasites were exposed to SNAP, a significant increase (1.8-fold) was detected only at 4 h posttreatment (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, at 2 h we detected a significant increase in the protein expression levels of CβS in response to oxidative stress of 1.51-fold, whereas under nitrosative stress, the highest protein level was observed at 4 h. The increases in protein expression levels of CβS under both stresses were lower than those observed for CS (Fig. 2Ai and Aii). Furthermore, during exposure to H2O2 and SNAP, the specific activity of CβS showed slight increases without significant variations over the time course (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Effects of oxidative and nitrosative stresses on CS and CβS protein expression, enzymatic activity, and total thiols levels in Leishmania braziliensis. (Ai) Western blot analysis of soluble extracts obtained from promastigotes exposed to the IC50 dose of H2O2 (550 μM) and the IC50 dose of SNAP (195 μM). (Aii) Modulation of CS and CβS expression in L. braziliensis exposed to in vitro oxidative or nitrosative stress. Densitometry analysis of the signals shown in panel A was carried out with ImageJ software. (B) Changes in CS and CβS activity in promastigotes exposed to H2O2 and SNAP. The specific enzymatic activity in soluble extracts from parasites was determined. (C) Total reduced thiol content (fold change) in treated and untreated promastigotes. The total thiol content was quantified using 5,5-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid). The results represent the average from three independent experiments performed in triplicate ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by a two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (**, P < 0.01 compared to the value at 0 h; ***, P < 0.001 compared to the value at 0 h). Fold change is the ratio of the value for the untreated sample (the value for the control was set equal to 1) to that for the treated sample.

The total intracellular thiol content was altered in response to oxidative and nitrosative stress in L. braziliensis promastigotes.

Comparative analysis of the total thiol contents in L. braziliensis parasites under oxidative and nitrosative stress revealed changes in the thiol contents in treated parasites compared with those in the untreated control. In promastigotes exposed to H2O2, the amount of total thiols increased slightly from the first hour of exposure (1.53-fold) but showed a significant increase (2.25-fold) after 2 h, followed by a decrease to 0.72-fold compared to that for the untreated control (Fig. 2C). Although during the first hour of exposure to SNAP we observed an increase in the level of total thiols of 2.13-fold, we noted a progressive decrease from 9.2 to 6.35 nmol (108 cells)−1 after 4 h of treatment, but the level remained even higher than that in the untreated control at 3.79 nmol (108 cells)−1 (Fig. 2C).

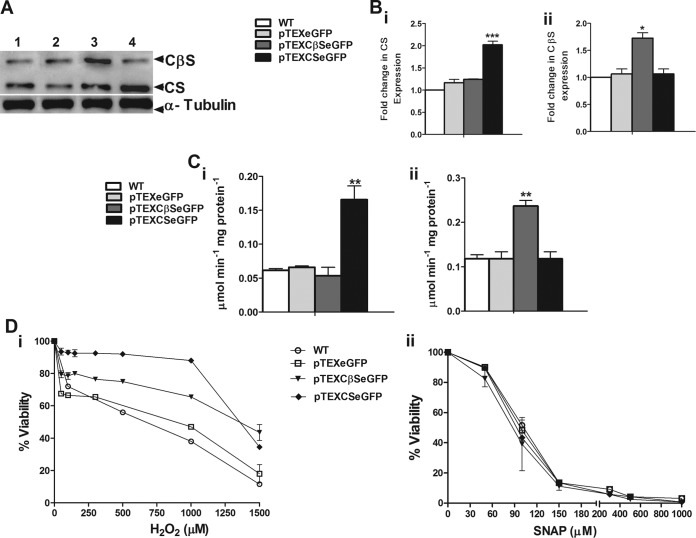

Functional rescue of CS activity with LbrCS and heterologous expression of LbrCβS in T. rangeli.

In order to investigate the activity of LbrCS in vitro, we examined its ability to rescue the activity of CS in a CS-deficient parasite like T. rangeli. As expected, introduction of a plasmid containing the LbrCS gene in epimastigotes of T. rangeli allowed expression of the activity of CS, which is absent in this parasite. The results revealed that T. rangeli carrying pTEXCSeGFP not only expressed CS protein but also showed a higher level of activity equivalent to that observed in lysates from wild-type promastigotes of L. braziliensis used as a control (0.072 μmol min−1 mg protein−1) (Fig. 3A, Bi, and Ci). Additionally, in T. rangeli parasites transfected with pTEXCβSeGFP, we observed a significant increase (1.62-fold) in CβS activity compared with that observed in the wild-type strain or parasites carrying the empty vector (Fig. 3A, Bii, and Cii).

FIG 3.

Functional rescue of CS activity and heterologous expression of LbrCβS in Trypanosoma rangeli. (A) Western blot analysis of soluble extracts obtained from epimastigotes of T. rangeli (Tr). Lane 1, WT; lane 2, pTEXeGFP-transfected parasites; lane 3, pTEXCβSeGFP-transfected parasites; lane 4, pTEXCSeGFP-transfected parasites; lane 5, positive control (promastigotes of L. braziliensis [Lb]). (B) Densitometry analysis shows the fold change in CS (i) and CβS (ii) expression determined by Western blotting (A). (C) The specific activity of CS (i) and CβS (ii) in total extracts from transfected and WT parasites was determined. (D) Susceptibility of transformed and WT T. rangeli epimastigotes after exposure to various concentrations of H2O2 (i) and SNAP (ii) in triplicate wells. Viability was assessed using alamarBlue assays. The results represent the average from three independent experiments performed in triplicate ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by a one- or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (**, P < 0.01 compared to WT; ***, P < 0.001 compared to WT).

Susceptibility of T. rangeli expressing L. braziliensis CS and CβS to H2O2 and SNAP in vitro.

In order to evaluate the susceptibility of T. rangeli expressing LbrCS or LbrCβS to oxidative or nitrosative stress, epimastigotes were exposed to different concentrations of H2O2 and SNAP for 48 h, and the effect of this exposure on parasite viability was assessed. The IC50 for T. rangeli epimastigotes overexpressing LbrCS showed a 2.42-fold increase in response to H2O2 compared to the IC50s for the wild-type and pTEXeGFP-transfected parasites (Table 1). Interestingly, parasites overexpressing the LbrCβS protein were also more resistant (2.3 times) to H2O2 than wild-type parasites (Table 1). The dose-response curves showed a marked difference in resistance to H2O2 between T. rangeli wild-type and mutant strains at the lower concentrations, where clear differences were observed from 100 to 150 μM H2O2. However, the major difference in percent viability was observed at 150 μM H2O2, with the viability of the mutant parasites being increased 45% compared to that of the wild-type parasites. In contrast, at higher H2O2 doses (>300 μM) the viability of all T. rangeli strains was inhibited (Fig. 3Di). Unlike the results for H2O2-induced stress observed, expression of LbrCS or LbrCβS did not alter the response of T. rangeli to nitrosative stress induced by SNAP (Fig. 3Dii), with the IC50s for the exposed parasites being revealed to be similar to those for wild-type control cells (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Differential susceptibility of wild-type and pTEXeGFP-, pTEXCSeGFP-, or pTEXCβSeGFP-transfected parasites to H2O2 or SNAP-induced stress

| Parasite | Plasmid transfected into cells | IC50a (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| H2O2 | SNAP | ||

| T. rangeli | WTb | 66 ± 4 | 353 ± 10 |

| pTEXeGFP | 69 ± 0.3 | 316 ± 17 | |

| pTEXCSeGFP | 160 ± 19** | 402 ± 49 | |

| pTEXCβSeGFP | 153 ± 18** | 345 ± 3 | |

| L. braziliensis | WT | 560 ± 4 | 99 ± 13 |

| pTEXeGFP | 558 ± 3 | 96 ± 3 | |

| pTEXCSeGFP | 1,368 ± 7*** | 93 ± 6 | |

| pTEXCβSeGFP | 1,551 ± 33*** | 80 ± 17 | |

Values are means ± SEMs. Significant differences were detected by one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

WT, wild-type cells.

Protein expression and activity characterization for L. braziliensis overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS.

To evaluate whether the overexpression of the CS and CβS proteins in L. braziliensis results in increased tolerance to oxidative stress, we initially generated stable promastigotes overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS using the episomal vector pTEXeGFP carrying the LbrCS and LbrCβS genes and analyzed the response of the transfected promastigotes to H2O2 and SNAP treatment. The relative abundance and specific activity of CS and CβS in L. braziliensis promastigote forms carrying pTEXCSeGFP or pTEXCβSeGFP were evaluated by Western blotting and enzyme activity assays, showing significant differences between the mutant lines and the wild type or parasites carrying the empty vector (Fig. 4A, Bi, Bii, and C). We observed an increase in the protein expression level of 2.02-fold in the parasites carrying pTEXCSeGFP, and in the parasite carrying pTEXCβSeGFP, this increase was 1.72-fold compared to the value for the wild type and parasites carrying the empty vector. As expected, the specific CS and CβS activities were significantly increased in parasites overexpressing these genes (Fig. 4C). As observed in Fig. 4Ci, the parasites transfected with the plasmid carrying pTEXCSeGFP or pTEXCβSeGFP showed 2.7-fold and 2.0-fold higher CS and CβS activities, respectively, than the control parasites (Fig. 4Cii).

FIG 4.

Functional characterization of CS and CβS expression in Leishmania braziliensis transformed with recombinant forms of these proteins. (A) Western blot analysis of soluble extracts obtained from promastigotes of L. braziliensis. Lane 1, WT; lane 2, pTEXeGFP-transfected parasites; lane 3, pTEXCβSeGFP-transfected parasites; lane 4, pTEXCSeGFP-transfected parasites. (B) Densitometry analysis shows the fold change in CS (i) and CβS (ii) expression determined by Western blotting (A). (C) The specific activity of CS (i) and CβS (ii) was determined in total extracts from transfected and WT parasites. (D) Susceptibility of transformed and WT promastigotes after exposure to various concentrations of H2O2 (i) and SNAP (ii) in triplicate wells. Viability was assessed using alamarBlue assays. The results represent the average from three independent experiments performed in triplicate ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by a one- or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (*, P < 0.05 compared to WT; **, P < 0.01 compared to WT; ***, P < 0.001 compared to WT).

Overexpression of LbrCS and LbrCβS increases survival against oxidative stress in promastigotes of L. braziliensis.

Promastigotes overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS showed significantly higher levels of resistance to H2O2 but not to SNAP (Fig. 4Di and ii). Under oxidative stress, the IC50s for promastigotes overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS increased 2.42- and 2.7-fold, respectively, compared to those for wild-type and mock-transfected parasites (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 4Di, the dose-response curves showed quite similar profiles for both LbrCS- and LbrCβS-overexpressing parasite lines, suggesting a decrease in susceptibility to H2O2 at lower doses, particularly for parasites overexpressing CS. For these, the percent parasite viability remained higher than 88% even at a 1,000 μM exposure, whereas the percent viabilities were 47% for parasites transfected with pTEXeGFP and 32% for wild-type parasites. We found a direct relationship between LbrCS overexpression and increased CS activity and susceptibility to H2O2 exposure. This finding was supported by the high correlation between CS expression (r = 0.91; P = 0.0018) and specific activity (r = 0.90; P = 0.0026) with susceptibility to H2O2 exposure that was seen. A clear positive correlation between LbrCβS overexpression and specific activity with susceptibility to H2O2 exposure was also found, as evidenced by the high correlation coefficients obtained: r was equal to 0.94 (P = 0.0005) for the correlation with LbrCβS overexpression, and r was equal to 0.77 (P = 0.02) for the correlation with LbrCβS specific activity. In contrast, there was no detectable correlation between CS and CβS activities and parasite susceptibility to nitrosative stress treatment (data not shown).

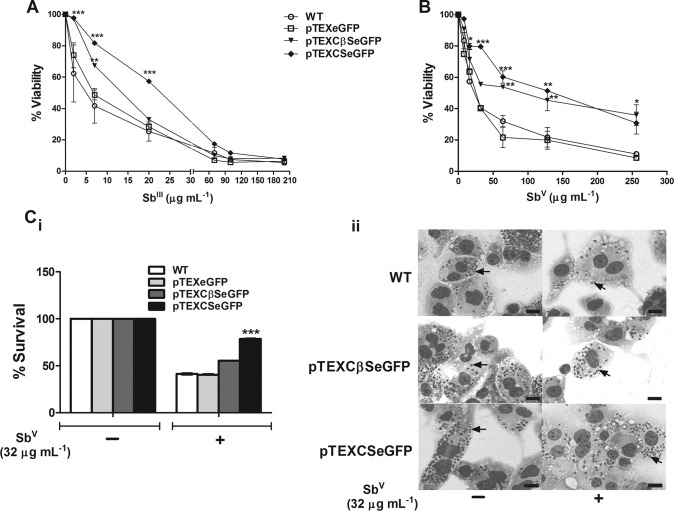

Overexpression of LbrCS and LbrCβS by L. braziliensis enhances resistance to SbIII and to SbV.

Analyses of dose-response curves showed that the viability of promastigotes overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS was reduced by only 3% with treatment with SbIII at 2 μg ml−1. However, at a dose of 7 μg ml−1 of SbIII, viability reductions of 18.0% and 32.5% were observed for pTEXCSeGFP- and pTEXCβSeGFP-transfected parasites, respectively, and for the control pTEXeGFP-transfected and WT parasites, these values were only 50 and 65%, respectively (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, parasites overexpressing LbrCS showed a 43% reduction in viability when they were treated with SbIII at a concentration of 20 μg ml−1 (Fig. 5A). In addition, we found increased IC50s for LbrCS- and LbrCβS-overexpressing L. braziliensis parasites treated with SbIII, where promastigotes overexpressing LbrCS were shown to be 4.8-fold more resistant to SbIII exposure than the WT parasites, with the level of tolerance increasing from 4.8 μg ml−1 for WT parasites to 23.2 μg ml−1 for LbrCS-overexpressing parasites (Table 2).

FIG 5.

Effect of antimonial treatment of Leishmania braziliensis overexpressing CS and CβS. Susceptibility to antimony was assessed in cells infected with WT and plasmid-transfected L. braziliensis parasites. (A) Dose-response curves in promastigotes treated with different doses of SbIII. (B) Dose-response curves in intracellular amastigotes treated with different doses of SbV. (Ci) Intracellular survival of L. braziliensis amastigotes infecting THP-1 macrophages treated with SbV (32 μg/ml). (Cii) Light micrograph of THP-1 human macrophages containing amastigotes (arrows) and treated with 32 μg/ml of SbV. Giemsa staining was used. The results represent the average from three independent experiments performed in duplicate ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by a one- or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (*, P < 0.05 compared to WT; **, P < 0.01 compared to WT; ***, P < 0.001 compared to WT). Bars = 20 μm.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of L. braziliensis wild-type and pTEXeGFP-, pTEXCβSeGFP-, or pTEXCSeGFP-transfected cell lines to SbIII and SbV

| Plasmid transfected into cells | IC50a (μg ml−1) |

|

|---|---|---|

| SbIII | SbV | |

| WTb | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 28.4 ± 2.49 |

| pTEXeGFP | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 26.9 ± 0.15 |

| pTEXCβSeGFP | 12.4 ± 0.11** | 88 ± 17.7** |

| pTEXCSeGFP | 23.2 ± 0.21** | 134 ± 2.35** |

Values are mean ± SEMs. Significant differences were detected by one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (**, P < 0.001). IC50s for antimonial drugs are presented in micrograms per milliliter, where 1 μg/ml of SbIII is equal to 1.63 μM SbIII.

WT, wild-type cells.

Upon observation of this phenotypic alteration, we also evaluated whether overexpression of CS and CβS by L. braziliensis could modulate the SbV (Glucantime) susceptibility profile in intracellular amastigotes. For that, THP-1-derived macrophages were infected with wild-type, mock-transfected, or LbrCS- or LbrCβS-overexpressing promastigotes and then subjected to SbV treatment for 72 h. As expected, the sensitivity patterns of transfected parasites exposed to SbIII and SbV were similar to each other. The results demonstrated that, even for the higher dose tested (256 μg ml−1), amastigotes overexpressing LbrCS or LbrCβS displayed an increased percent viability compared with that for wild-type or mock-transfected amastigotes in response to SbV (Fig. 5B). Treatment of infected macrophages with a 32-μg ml−1 dose of SbV (close to the intracellular IC50 value for the wild-type strain) showed that the CS-overexpressing parasites exhibited a significant increase in survival (78.3%) compared to the wild-type parasites or parasites transfected with pTEXeGFP (∼41%) (Fig. 5Ci). This difference in parasite survival was evidenced by the increase in the number of amastigotes per macrophage after treatment (Fig. 5Cii). Similarly, the IC50s increased 3.7- and 4.7-fold for intracellular amastigotes overexpressing LbrCβS and LbrCS, respectively (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report that CS and CβS, key enzymes in the l-cysteine de novo and reverse transsulfuration (RTS) biosynthetic pathways, play an important role protecting L. braziliensis against oxidative stress. Although these enzymes are evolutionarily related to the human CβS, comparative sequence analyses showed that LbrCS and LbrCβS are present as single-copy genes in L. braziliensis and lack the essential catalytic heme-binding site and regulatory carboxyl-terminal domain typically found in the human CβS (34, 35).

Additionally, LbrCS possesses the SAT binding domain, which has been described to be present in other organisms, such as plants, bacteria, and Old World Leishmania species, but is missing in the related CβS enzymes from humans (23, 36). Crystallography studies of CS from Old World Leishmania species have confirmed that the interaction between SAT and CS forms the regulatory complex CS-SAT, allowing the design of peptides based on the C terminus of SAT that are possible selective inhibitors for the CS enzyme (24, 37).

Similar to other trypanosomatids, L. braziliensis has two pathways for generating cysteine, having active CS and CβS in both life cycle stages (23, 38, 39). Interestingly, our results demonstrated a stage-specific regulation of the protein levels and activity of LbrCS and LbrCβS. While increased protein expression and activity were observed for LbrCS in intracellular amastigotes (mammalian form), the opposite was found for LbrCβS, revealing higher expression levels and activity in the promastigote stage (insect form). Our findings are consistent with those of prior studies on L. panamensis axenic amastigotes, where higher CS expression levels were observed in amastigotes than in promastigotes (40). Moreover, the increased CβS levels and activity in L. braziliensis promastigotes found in the present study are consistent with those found in studies on T. cruzi epimastigotes (insect forms), which exhibit both significantly higher CβS levels and significantly higher CβS activity than the mammalian intracellular forms (27, 38, 41).

The stage-specific regulation of CS and CβS may be due to a likely association between the cysteine biosynthetic pathways and the complex life cycle of Leishmania spp. and T. cruzi. While the de novo pathway via CS seems to occur predominantly in the intracellular mammalian form, the RTS mediated by CβS is predominant in the insect form. This observation is consistent with the fact that T. rangeli and T. brucei, parasites without an intracellular replicative stage in the mammal host, possess only the RTS pathway for cysteine biosynthesis (27, 42), whereas monoxenic parasites like Entamoeba spp. solely possess the de novo or assimilatory pathway (17). In contrast, herein we report both the CS and CβS active pathways in the New World L. braziliensis parasites, which is in agreement with the findings of previous studies using Old World L. major parasites (23). The redundancy from the presence of these two alternative routes for cysteine synthesis observed in Leishmania spp. and T. cruzi may be related to the availability of exogenous nutrients, which differs considerably between invertebrate and mammalian hosts (23). While Leishmania promastigotes reside in a glucose-rich and slightly alkaline environment with few amino acids in the sand fly vectors, amastigotes nestled within the phagolysosomes of human macrophages cope with an acidic environment where glucose is scarce and amino acids are abundant (43).

Furthermore, the presence of two active biosynthetic pathways for cysteine synthesis in Leishmania spp. may be due to the crucial need for cysteine to support the requirements of antioxidant thiol synthesis, especially trypanothione [T(SH)2] (15, 44). In this sense, we found that increased levels of protein expression and activity of LbrCS and LbrCβS led to elevated total thiol concentrations in response to in vitro oxidative and nitrosative stress in L. braziliensis, confirming the association between cysteine biosynthesis and the response to oxidative and nitrosative stress.

Along with the CS de novo pathway, the RTS pathway has also been considered an alternative source for supplying redox potential to parasite cells under oxidative stress (45). Our findings concerning the regulation of LbrCS and LbrCβS are the first report of the activation of these enzymes under oxidative and nitrosative stress. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of this regulation remains unclear, and further studies are needed to investigate these associations.

In order to better understand the role of LbrCS and LbrCβS under stress conditions, functional characterization of these enzymes was undertaken using a genetic complementation assay to rescue the CS activity and heterologous protein expression of CβS in T. rangeli. It was recently demonstrated that T. rangeli does not have a functional CS and, thus, does not perform de novo cysteine biosynthesis, being highly susceptible to oxidative stress and having a lower total thiol content than T. cruzi (27). By rescuing the CS activity in T. rangeli, the transfected parasite showed higher rates of survival than wild-type epimastigotes in the presence of increasing concentrations of H2O2. Similarly, overexpression of LbrCβS by T. rangeli also conferred resistance to oxidative stress in epimastigotes. Taken together, these results indicate that T. rangeli is a valid model for functional studies and highlight the significant role of LbrCS and LbrCβS in response to oxidative stress but not to nitrosative stress.

The protective relationship between the higher levels of protein expression and activity of LbrCS and LbrCβS and parasite survival under stress conditions was further demonstrated by the enhanced ability of L. braziliensis overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS to resist oxidative stress compared to that of the wild-type parasites. Taken together, data from studies on the functional rescue of LbrCS and LbrCβS in T. rangeli and overexpression of these proteins in L. braziliensis provide a strong argument on their role against oxidative stress, as they are in accordance with the results of previous studies with Entamoeba spp. and plants (22, 46, 47).

Although there are a few available data about the overexpression of CβS and its role under oxidative stress, our study is the first to demonstrate this function of CβS in L. braziliensis. Along with our evidence from studies of LbrCβS overexpression, inhibition of CβS and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) activity or small interfering RNA-mediated CβS knockdown was found to increase the level of cellular death induced by oxidative stress in mesenchymal progenitor cells (48).

The ability of L. braziliensis promastigotes overexpressing LbrCS and LbrCβS to withstand the oxidative stress induced by antimonial compounds showed the decreased susceptibility of the parasites to SbIII exposure. A positive correlation between the expression or specific activity of CS and CβS and parasite survival after exposure to SbIII was found. Further testing using amastigotes within THP-1 human macrophages exposed to SbV (Glucantime) showed a significant loss of susceptibility to SbV treatment for both LbrCS- and LbrCβS-overexpressing parasites, confirming the positive correlation between protein expression and activity and parasite survival rates after exposure to SbV (data not shown). Taken together, our data suggest that the increased tolerance to antimonial compounds mediated by the CS and CβS enzymes may be due to the increased activities leading to cysteine production in support of the need for glutathione and trypanothione synthesis required for antimony detoxification (29, 49).

Increasing thiol levels have been considered one of the major mechanisms for SbIII detoxification observed in resistant Leishmania lines (50). While cysteine, glutathione, and trypanothione levels were significantly increased in L. amazonensis promastigotes resistant to SbIII in the laboratory, only SbIII-resistant Leishmania infantum parasites showed a significant increase in cysteine levels (51, 52). In addition, the levels of the thiols glutathione and trypanothione have been found to be significantly lower in clinical isolates of L. donovani sensitive to SbIII treatment than in resistant lines (53). Furthermore, upregulation of the expression of genes involved in the cysteine, glutathione, and trypanothione biosynthesis pathways (CβS, γ-glutamyl cysteine synthetase, ornithine decarboxylase, trypanothione synthetase, trypanothione reductase, and spermidine synthase) was observed in antimony-resistant clinical isolates (33, 52, 54).

Since cysteine forms the basic building block of all thiols, our results suggest that CS and CβS have an important role in L. braziliensis survival under oxidative stress conditions and opens the question of whether this also may occur in other Leishmania species. Interestingly, we have clearly demonstrated herein that changes in the protein expression and activity levels of LbrCS and LbrCβS might be related to antimony efficacy, which reinforces the idea that cysteine can be involved directly or indirectly in resistance phenotypes. Overall, our findings, together with the fact that mammals lack the pathway for de novo biosynthesis of cysteine, make CS a good exploitable drug target, as the SAT-binding domain represents an excellent candidate for the rational design of selective inhibitors of New World Leishmania parasites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mariel A. Marlow for the English revision.

I.R. and J.T. give a special acknowledgment in memory of John Walker, our friend and colleague.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herwaldt BL. 1999. Leishmaniasis. Lancet 354:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minodier P, Noël G, Blanc P, Uters M, Retornaz K, Garnier JM. 2007. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in children. Med Trop (Mars) 67:73–78. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori S, Schifanella L, Corbellino M. 2012. Leishmaniasis: new insights from an old and neglected disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goto H, Lindoso JA. 2010. Current diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 8:419–433. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lessa MM, Lessa HA, Castro TW, Oliveira A, Scherifer A, Machado P, Carvalho EM. 2007. Mucosal leishmaniasis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 73:843–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burchmore RJ, Barrett MP. 2001. Life in vacuole—nutrient acquisition by Leishmania amastigotes. Int J Parasitol 31:1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivier M, Gregory DJ, Forget G. 2005. Subversion mechanisms by which Leishmania parasites can escape the host immune response: a signaling point of view. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:293–305. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.293-305.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dostálová A, Volf P. 2012. Leishmania development in sand flies: parasite-vector interactions overview. Parasit Vectors 5:276. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Assche T, Deschacht M, da Luz RA, Maes L, Cos P. 2011. Leishmania-macrophage interactions: insights into the redox biology. Free Radic Biol Med 51:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frézard F, Demicheli C, Kato KC, Reis PG, Lizarazo-Jaimes EH. 2013. Chemistry of antimony-based drugs in biological systems and studies of their mechanism of action. Rev Inorg Chem 33:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mookerjee Basu J, Mookerjee A, Sen P, Bhaumik S, Banerjee S, Naskar K, Choudhuri SK, Saha B, Raha S, Roy S. 2006. Sodium antimony gluconate induces generation of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide via phosphoinositide 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in Leishmania donovani-infected macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1788–1797. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1788-1797.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta A, Shaha C. 2006. Mechanism of metalloid-induced death in Leishmania spp.: role of iron, reactive oxygen species, Ca2+, and glutathione. Free Radic Biol Med 40:1857–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baiocco P, Colotti G, Franceschini S, Ilari A. 2009. Molecular basis of antimony treatment in leishmaniasis. J Med Chem 52:2603–2612. doi: 10.1021/jm900185q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irigoín F, Cibils L, Comini MA, Wilkinson SR, Flohé L, Radi R. 2008. Insights into the redox biology of Trypanosoma cruzi: trypanothione metabolism and oxidant detoxification. Free Radic Biol Med 45:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krauth-Siegel RL, Comini MA. 2008. Redox control in trypanosomatids, parasitic protozoa with trypanothione-based thiol metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1780:1236–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairlamb AH, Blackburn P, Ulrich P, Chait BT, Cerami A. 1985. Trypanothione: a novel bis(glutathionyl)spermidine cofactor for glutathione reductase in trypanosomatids. Science 227:1485–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.3883489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nozaki T, Ali V, Tokoro M. 2005. Sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism in parasitic protozoa. Adv Parasitol 60:1–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krauth-Siegel RL, Leroux AE. 2012. Low-molecular-mass antioxidants in parasites. Antioxid Redox Signal 17:583–607. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas D, Surdin-Kerjan Y. 1997. Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61:503–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aitken SM, Kirsch JF. 2005. The enzymology of cystathionine biosynthesis: strategies for the control of substrate and reaction specificity. Arch Biochem Biophys 433:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman-Salit A, Wirtz M, Hell R, Wade RC. 2009. A mechanistic model of the cysteine synthase complex. J Mol Biol 386:37–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozaki T, Asai T, Sanchez LB, Kobayashi S, Nakazawa M, Takeuchi T. 1999. Characterization of the gene encoding serine acetyltransferase, a regulated enzyme of cysteine biosynthesis from the protist parasites Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar. Regulation and possible function of the cysteine biosynthetic pathway in Entamoeba. J Biol Chem 274:32445–32452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams RA, Westrop GD, Coombs GH. 2009. Two pathways for cysteine biosynthesis in Leishmania major. Biochem J 420:451–462. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raj I, Kumar S, Gourinath S. 2012. The narrow active-site cleft of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Leishmania donovani allows complex formation with serine acetyltransferases with a range of C-terminal sequences. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68:909–919. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912016459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides P, Ballew RM, Huson DH, Wortman JR, Zhang Q, Kodira CD, Zheng XH, Chen L, Skupski M, Subramanian G, Thomas PD, Zhang J, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson C, Broder S, Clark AG, Nadeau J, McKusick VA, Zinder N, Levine AJ, Roberts RJ, Simon M, Slayman C, Hunkapiller M, Bolanos R, Delcher A, Dew I, Fasulo D, Flanigan M, Florea L, Halpern A, Hannenhalli S, Kravitz S, Levy S, Mobarry C, Reinert K, Remington K, Abu-Threideh J, Beasley E, et al. 2001. The sequence of the human genome. Science 291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendricks L, Wright N. 1979. Diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis by in vitro cultivation of saline aspirates in Schneider's Drosophila medium. Am J Trop Med Hyg 28:962–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero I, Téllez J, Yamanaka LE, Steindel M, Romanha AJ, Grisard EC. 2014. Transsulfuration is an active pathway for cysteine biosynthesis in Trypanosoma rangeli. Parasit Vectors 7:197. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. 1980. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1). Int J Cancer 26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyllie S, Fairlamb AH. 2006. Differential toxicity of antimonial compounds and their effects on glutathione homeostasis in a human leukaemia monocyte cell line. Biochem Pharmacol 71:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero IC, Saravia NG, Walker J. 2005. Selective action of fluoroquinolones against intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis in vitro. J Parasitol 91:1474–1479. doi: 10.1645/GE-3489.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res 8:175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Decuypere S, Vanaerschot M, Brunker K, Imamura H, Müller S, Khanal B, Rijal S, Dujardin JC, Coombs GH. 2012. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in natural Leishmania populations vary with genetic background. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koutmos M, Kabil O, Smith JL, Banerjee R. 2010. Structural basis for substrate activation and regulation by cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) domains in cystathionine {beta}-synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:20958–20963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011448107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ereño-Orbea J, Majtan T, Oyenarte I, Kraus JP, Martínez-Cruz LA. 2013. Structural basis of regulation and oligomerization of human cystathionine β-synthase, the central enzyme of transsulfuration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E3790–E3799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313683110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feldman-Salit A, Wirtz M, Lenherr ED, Throm C, Hothorn M, Scheffzek K, Hell R, Wade RC. 2012. Allosterically gated enzyme dynamics in the cysteine synthase complex regulate cysteine biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Structure 20:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fyfe PK, Westrop GD, Ramos T, Müller S, Coombs GH, Hunter WN. 2012. Structure of Leishmania major cysteine synthase. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 68:738–743. doi: 10.1107/S1744309112019124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nozaki T, Shigeta Y, Saito-Nakano Y, Imada M, Kruger WD. 2001. Characterization of transsulfuration and cysteine biosynthetic pathways in the protozoan hemoflagellate, Trypanosoma cruzi. Isolation and molecular characterization of cystathionine beta-synthase and serine acetyltransferase from Trypanosoma. J Biol Chem 276:6516–6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giordana L, Mantilla BS, Santana M, Silber AM, Nowicki C. 2014. Cystathionine γ-lyase, an enzyme related to the reverse transsulfuration pathway, is functional in Leishmania spp. J Eukaryot Microbiol 61:204–213. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker J, Vasquez JJ, Gomez MA, Drummelsmith J, Burchmore R, Girard I, Ouellette M. 2006. Identification of developmentally-regulated proteins in Leishmania panamensis by proteome profiling of promastigotes and axenic amastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 147:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marciano D, Santana M, Nowicki C. 2012. Functional characterization of enzymes involved in cysteine biosynthesis and H(2)S production in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol 185:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okalang U, Nanteza A, Matovu E, Lubega GW. 2013. Identification of coding sequences from a freshly prepared Trypanosoma brucei brucei expression library by polymerase chain reaction. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 4:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenzweig D, Smith D, Opperdoes F, Stern S, Olafson RW, Zilberstein D. 2008. Retooling Leishmania metabolism: from sand fly gut to human macrophage. FASEB J 22:590–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fairlamb AH, Cerami A. 1992. Metabolism and functions of trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida. Annu Rev Microbiol 46:695–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.003403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niu WN, Yadav PK, Adamec J, Banerjee R. 2015. S-Glutathionylation enhances human cystathionine β-synthase activity under oxidative stress conditions. Antioxid Redox Signal 22:350–361. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youssefian S, Nakamura M, Orudgev E, Kondo N. 2001. Increased cysteine biosynthesis capacity of transgenic tobacco overexpressing an O-acetylserine(thiol) lyase modifies plant responses to oxidative stress. Plant Physiol 126:1001–1011. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ning H, Zhang C, Yao Y, Yu D. 2010. Overexpression of a soybean O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase-encoding gene GmOASTL4 in tobacco increases cysteine levels and enhances tolerance to cadmium stress. Biotechnol Lett 32:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-0178-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox B, Schantz JT, Haigh R, Wood ME, Moore PK, Viner N, Spencer JP, Winyard PG, Whiteman M. 2012. Inducible hydrogen sulfide synthesis in chondrocytes and mesenchymal progenitor cells: is H2S a novel cytoprotective mediator in the inflamed joint? J Cell Mol Med 16:896–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wyllie S, Cunningham M, Fairlamb A. 2004. Dual action of antimonial drugs on thiol redox metabolism in the human pathogen Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem 279:39925–39932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukhopadhyay R, Dey S, Xu N, Gage D, Lightbody J, Ouellette M, Rosen BP. 1996. Trypanothione overproduction and resistance to antimonials and arsenicals in Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:10383–10387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El Fadili K, Messier N, Leprohon P, Roy G, Guimond C, Trudel N, Saravia NG, Papadopoulou B, Légaré D, Ouellette M. 2005. Role of the ABC transporter MRPA (PGPA) in antimony resistance in Leishmania infantum axenic and intracellular amastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:1988–1993. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1988-1993.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.do Monte-Neto RL, Coelho AC, Raymond F, Légaré D, Corbeil J, Melo MN, Frézard F, Ouellette M. 2011. Gene expression profiling and molecular characterization of antimony resistance in Leishmania amazonensis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mandal G, Wyllie S, Singh N, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH, Chatterjee M. 2007. Increased levels of thiols protect antimony unresponsive Leishmania donovani field isolates against reactive oxygen species generated by trivalent antimony. Parasitology 134:1679–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukherjee A, Padmanabhan PK, Singh S, Roy G, Girard I, Chatterjee M, Ouellette M, Madhubala R. 2007. Role of ABC transporter MRPA, gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase and ornithine decarboxylase in natural antimony-resistant isolates of Leishmania donovani. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]